Like many progressives, I became more active in politics during the 2004 U.S. presidential campaign. Going online in search of alternatives to the mainstream coverage of the election, I came across plenty of articles by Thom Hartmann: about media manipulation by the candidates; about the possibility of vote tampering; and about how we can “restore democracy” in the U.S. I admired his unflinching attention to the worrisome details that others overlooked. (I’m not the only one. His reporting has earned a Project Censored award, for independent journalism on issues that are ignored by the major news media.)

A visit to Hartmannf’s website (www.thomhartmann.com) reveals a writing career that covers more than just politics: he’s written fourteen books, on topics ranging from spirituality to the environment to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In We the People: A Call to Take Back America (Coreway Media), Hartmann and illustrator Neil Cohn use a simple comic-book format to describe how corporations have come to dominate our government and culture. The Prophet’s Way: A Guide to Living in the Now (Park Street Press) earned Hartmann an invitation to a private audience with Pope John Paul II in 1998. Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight (Three Rivers Press), about our dwindling world oil supply, caught the attention of the Dalai Lama, who invited Hartmann to spend a week with him in Dharamsala, India, home of the Tibetan government-in-exile. Hartmann’s most recent book, What Would Jefferson Do? (Harmony), traces the history of democracy in the U.S. and includes specific recommendations for how we can rescue our system of government from corporate influence.

Born in 1951, Hartmann grew up in conservative, working-class Lansing, Michigan, and became involved in politics at a young age. When he was thirteen, he campaigned door-to-door for Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. Three years later, however, he was protesting against the Vietnam War.

Hartmann also started writing early in life. “By the time I was sixteen,” he says, “my bedroom wall was papered with rejection slips, mostly for terrible poetry.” Though he was a committed agnostic as a teenager, vivid experiences with spiritual teachers ignited an interest in nonscientific truths, and he briefly taught meditation himself. For ten years, Hartmann worked in radio as a DJ, news reporter, and program director. Then, in 1978, he left radio to open the New England Salem Children’s Village, a residential treatment program for emotionally disturbed and abused children. He went on to work with the international Salem program, based in Europe, to set up famine-relief efforts, hospitals, and refugee centers in Africa, Europe, South America, and Asia. In 1997, Hartmann founded the Hunter School in New Hampshire, for children with ADHD. He has successfully started seven businesses, including an advertising agency, a publishing company, and an herbal-tea company.

Hartmann returned to radio two years ago with a nationally syndicated talk show, The Thom Hartmann Program: Uncommon Sense from the Radical Middle. In many markets, the show goes head-to-head with Rush Limbaugh in the noon-to-three time slot. In addition to being broadcast by radio stations across the country, it’s available via the Sirius Satellite Radio system and on RadioPower.org and WhiteRoseSociety.org.

Hartmann seems to have mastered the talk-radio genre. Ready to engage with callers of any type, he has a head full of facts and figures, and an earnestness that suits the format. Unlike most talk-radio hosts, however, he seems never to get angry nor impugn anyone’s character or motives. (He’ll even give Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld the benefit of the doubt.)

Hartmann, who lived in Montpelier, Vermont, for the past decade, moved in April to Portland, Oregon, where he does a local morning talk-radio show in addition to his syndicated program. He and his wife, Louise, to whom he’s been married for more than thirty years, have three grown children. When I interviewed him by telephone in early January 2005, he was still living in Montpelier. Throughout our conversation, Hartmann displayed a warmth and a sense of humor that were the equal of his probing thoughtfulness.

THOM HARTMANN

Guinness: The exit polls in the November 2004 presidential election heavily favored losing candidate John Kerry. A number of apparently unbiased commentators are saying that polls just aren’t working anymore. Does that make sense?

Hartmann: No, it doesn’t. We’re being told by the media that we polled too many women, or we polled too early in the day, but they’re grasping at straws. Is it a coincidence that exit-polling — a process that’s been fine-tuned for fifty years and is considered so reliable that it’s used to confirm the accuracy of elections in Third World countries — suddenly became inaccurate where electronic voting is widely used? Is it a coincidence that these were all close races that Republicans won, sometimes by upset? Is it a coincidence that, in the small number of counties where paper ballots were used, the difference between the polls and the actual vote was negligible?

Keep in mind, we’ve got some rather aggressive disinformation machines out there: the right-wing talk-radio machine, the Murdoch empire, the Moonie media machine of the Washington Times and United Press International, and the right-wing think tanks originally founded by Joe Coors and company. Nowadays even National Public Radio sounds more and more like mainstream media, because it’s fighting for survival. Congress holds the purse strings, and the Right controls Congress these days.

Guinness: I’ve heard that nearly 20 percent of the American public doubts the result of the 2004 presidential election. Is there any evidence that the election was subject to fraud or significant irregularities?

Hartmann: Bev Harris, who operates the website www.blackboxvoting.org, has been stubbornly pursuing confirmation of the election results in the Florida 2004 presidential election. She has gone county by county and asked to see evidence of the results. Counties that use optical scanners have poll tapes — printouts produced by each scanner on election day. In one county she was presented with tapes produced on November 15; she later found the real November 2 tapes in the garbage. In another county that used computerized voting, no government worker knew enough about the system to access any information for Harris. It turned out that an unidentified representative of the voting-machine company had been called in on election day to run the computer and tabulate the vote.

The unfortunate reality is that about 80 percent of the vote was either taken on or counted by computers that are programmed by private corporations, and these corporations say we have no business asking how they program their computers. These voting machines leave no paper trail. There’s no way to audit them. There’s no proof that if you push button A, the machine records A rather than B.

Guinness: We’re just taking their word for it, in other words, that our votes are being accurately recorded.

Hartmann: Yes. It’s faith-based voting. In Ohio they did a recount of votes recorded on punch cards or fill-in-the-blank ballots, but they counted only 3 percent. The other 97 percent we just have to hope was recorded accurately.

So the real question is: how do we know that we actually elected the people whom these private corporations say we elected? This is the real felony against democracy: the privatization of our voting system. I mean, if the Bush administration wants to privatize the concession stands at Yellowstone so that some corporation can profit off them, it’s somewhere between bad taste and abuse of power, but it’s not a crime against democracy. To privatize the vote, though, the beating heart of democracy — that is a crime.

Guinness: How long has electronic voting been going on?

Hartmann: It started to become widespread about fifteen years ago. But election fraud has always been with us. The challenge is to develop voting methods that are less vulnerable to fraud. Instead we’ve created a system that’s more vulnerable, because there’s no paper trail, and because it can be hacked: somebody can go in and change the information that’s stored in the computer. According to Congressman John Conyers Jr., that’s exactly what happened in Ohio in December 2004, weeks after the election: representatives of the voting-machine company made alterations to punch-card tabulators before the recount, apparently to ensure that the recount would match the initial results.

Guinness: Are the companies that control the voting machines all strongly Republican?

Hartmann: I wouldn’t say all of them, but certainly the high-visibility ones are. In 1996 Republican Congressman Chuck Hagel won an upset victory in a Nebraska Senate race in which votes were counted by machines designed and maintained by a company he headed. He went on to win reelection in 2002 with an unheard-of 83 percent of the vote.

If there were random errors with electronic voting, we would expect to find that the mistakes went sometimes in one party’s favor, sometimes in the other’s. Instead almost all the errors have proven to be in favor of the Republican candidates, with hundreds of votes going their way for every one mistake in favor of the Democrats.

Guinness: If the people in office are the ones who set up this voting system, how can it be fixed?

Hartmann: History tells us that the way citizens take back power, whether it be in 1776 or 2005, is by speaking out. Americans need to tell elected officials that we will not tolerate private corporations counting our vote in secret. We will not tolerate media that tell us only part of the truth. We want the government to enforce the Sherman Antitrust Act, which made it illegal for a single board of trustees to control numerous corporations, fix prices, and manipulate markets. That law constrained the power of capital in such a way that it still produced wealth, but also accomplished social good and didn’t corrupt government.

For all practical purposes, Ronald Reagan stopped enforcing the Sherman Act. Lack of enforcement led to a merger-and-acquisition mania, which led to the end of journalism as we once knew it. And as the Founders said: without an independent press, you can’t have a functional democracy. And how can you have an independent press when a handful of corporations control everything we see, hear, and read? We need to break up media conglomerates. We need to go back to a time when if you wanted to own a radio station or a television station or a newspaper, you actually had to live in the community it served.

The unfortunate reality is that about 80 percent of the vote was either taken on or counted by computers that are programmed by private corporations. . . . How do we know that we actually elected the people whom these private corporations say we elected? This is the real felony against democracy: the privatization of our voting system.

Guinness: When I was growing up, I was taught that the Russian people couldn’t think for themselves because they were subject to constant propaganda by their government. You seem to be suggesting that we’re in not such a different situation in the United States today.

Hartmann: I was in Russia when it was the Soviet Union, and I was in East Berlin when it was East Germany, and the people there were not dumb, uneducated cattle. The reality is that there were strong underground movements, and most citizens were well-informed — probably better informed than many Americans — precisely because they were so oppressed. We shouldn’t underestimate the role of these underground movements in bringing down the Soviet Union.

Guinness: So it’s not true what the conservatives claim: that Ronald Reagan’s military and economic policies are responsible for the fall of communism?

Hartmann: Reagan can’t take any credit for the fall of communism. Back in the 1960s the CIA was saying the Soviet Union could implode at any time. The Soviets couldn’t feed their people. Their economic system just didn’t work, because it was overlaid with a political autocracy, and autocracies have always self-destructed.

By the 1970s, the CIA was on a death watch. The hope was that the Soviet Union would go down quietly rather than violently, as societies often do. But its eventual collapse had nothing to do with Ronald Reagan. In fact, it happened on the watch of George Herbert Walker Bush. This whole idea that Reagan is responsible for the fall of the Soviet Union is revisionist history on the part of conservatives who want to elevate to sainthood one of our worst presidents. He declared war on the middle class. He drove up the largest debt we’d ever had (until George W. Bush came along). And thirty-two members of his administration were convicted of felonies — more than in any other administration in the history of the United States.

Guinness: So there was an active underground movement in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. To put it bluntly, are people in the U.S. too comfortable and satisfied and addicted to TV for that ever to happen here?

Hartmann: Actually, I think people are too frightened and too deep in debt. The problem is not that Americans are overfed and entertained to death. The problem is that nearly thirty years of conservative economic policies have wiped out most of the good jobs, exported most of our industries, and created the kind of Dickensian world that the conservatives want.

I think we find ourselves in a situation similar to the one I saw in Russia back in the 1970s and 1980s: it wasn’t that the average Russian was politically sophisticated, but that there was enough of an activist subculture to provide the basis for a movement. And here we have 20 percent of adults who think that the election was stolen: the people who read CommonDreams.org on the Web, the people who read The Sun, the people who listen to progressive talk radio. These people are forwarding e-mails to each other, doing what the pamphleteers who sparked the American Revolution did in 1773.

Guinness: Some observers are predicting that the growth of China and India will bring on an era of reduced U.S. influence in world affairs. Will that have an effect on democratic institutions at home?

Hartmann: No, there’s no relationship between the two, in my mind. There is a relationship, however, between the imperialistic policies of the United States and the decline of the middle class. If you look at the history of great empires, you’ll see they fall because they overextend themselves. They pour money into their military and into external expansion in search of resources, rather than building their internal infrastructure: their educational systems, their agricultural systems, their industrial systems. We’re going down that road very quickly right now, thanks to the neoconservative agenda. It’s fashionable to use the word empire again, you know. That’s an end-stage indicator for a nation. I just hope we haven’t gone so far that we can’t step back from the edge.

If there were random errors with electronic voting, we would expect to find that the mistakes went sometimes in one party’s favor, sometimes in the other’s. Instead almost all the errors have proven to be in favor of the Republican candidates.

Guinness: Do you think many Americans have a sense that something is wrong?

Hartmann: Pretty much everybody knows something is wrong. They know that they have to work harder every year to make ends meet. The problem is most people haven’t figured out that the destruction of the middle class is a result of politics. And they haven’t made that connection in part because those voices that would help them make that connection have, shall we say, not been exalted by the corporate media.

The golden age of the middle class — when a single wage earner could raise a family, pay all the medical expenses, take a vacation every year, and also have enough for retirement — was a direct result of the Sherman Antitrust Act, and also the Wagner Act of 1935, which guaranteed the right of workers to organize. Prior to the Sherman Act, we were in the Gilded Age, a period of poverty for the many and great wealth for the few. And what we’ve seen since Reagan and the rise of conservative economics is a rapid return to Gilded Age economics. Karl Rove, George W. Bush’s senior advisor, is always talking about his admiration for the William McKinley administration, at the end of the nineteenth century, when the country had a large working-class population struggling to care for kids and avoid eviction. The conservative agenda is about creating a similarly desperate, terrified, powerless, politically impotent working class that won’t put up much of a fight and doesn’t have the time to become educated about politics.

But people know that something is wrong. They’re feeling angry. So the right-wing demagogues come along and blame all the problems on illegal immigrants, or minorities who “want quotas,” or gays who want to get married, or those tree-hugging environmentalists who are worried about spotted owls. Over the last twenty-five years, the conservatives have pulled off one of the greatest con jobs in the history of the United States. They’ve done it very methodically, with their money and their think tanks and their right-wing talk-radio machine.

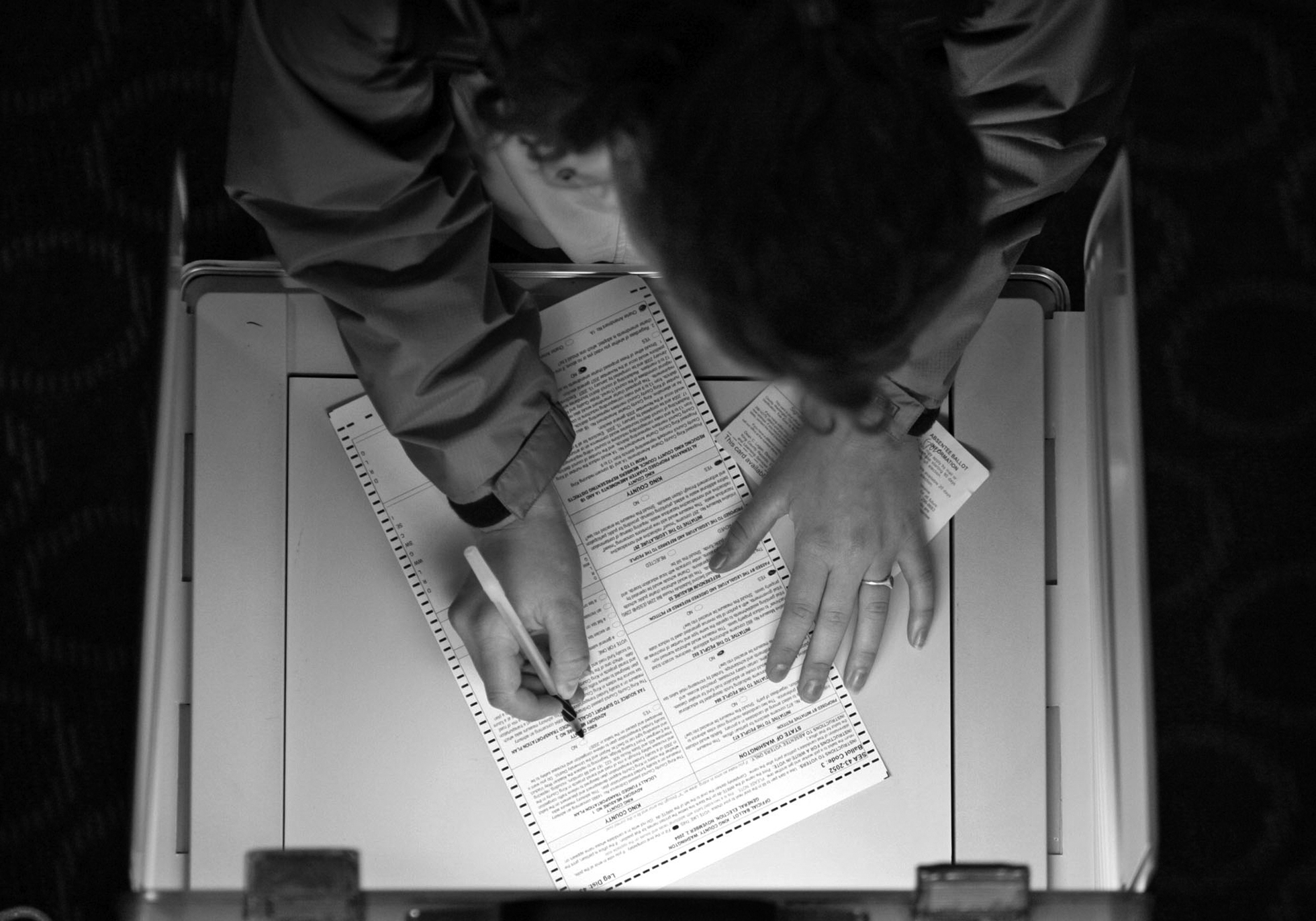

© AP Photo/Elaine Thompson

Guinness: You credit the golden age of the middle class to the Sherman and Wagner Acts. Couldn’t it also have been due to advances in technology, availability of cheap energy, and victory in World War II?

Hartmann: No, it wasn’t technology. There were massive leaps in technology in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, none of which produced large middle classes. And the first huge leap in the availability of cheap fuel in the United States was the transition from wood to coal in the latter half of the nineteenth century. And that produced a huge poor working class, not a middle class.

The reality is that in an unregulated, laissez-faire capitalist economy, middle classes don’t normally emerge. The first middle class that we had in the United States arose largely among whites from the late 1600s to the early 1800s as a result of cheap land, because we were able to take land from the Indians. Jefferson referred to that middle class as the “plowmanry.” They were family farmers who could produce what they needed, and so became self-sufficient. That trend started to go down the tubes with the rise of industrialization and the building of the railroads after the Civil War.

Guinness: Because we ran out of land?

Hartmann: Right. Again, keep in mind that cheap land is not normal, and a middle class is not normal either. What is normal — in our kind of civilization — is to have a small ruling elite and a large number of working poor. Think of the England that Charles Dickens described in A Christmas Carol.

In the 1930s, Franklin D. Roosevelt became president and instituted the New Deal. He saw that we lived in a different world. We didn’t have cheap land anymore. Our energy systems had changed; our industrial systems had changed. If we were going to have a middle class, he said, we would have to give the average working person power, to balance the power of industry and capital. And the two largest steps that he took to accomplish that were passing the Wagner Act and creating the Works Progress Administration, which made the government the employer of last resort, in the event that the marketplace didn’t provide enough jobs.

It was demand-driven economics, common-sense economics. What the New Deal did is put money in the pockets of poor people and working people, who then used that money to buy products, which created demand, which caused entrepreneurs to build products to meet this demand, which created jobs, which eliminated the need for the government make-work programs. This is the cycle. This is how it works. It was interference in the free market, pure and simple. And along with creating the New Deal, Roosevelt helped pass laws constraining the activity of corporations and created the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Social Security system. All of these things together created the middle class.

Conservatives today are hellbent on dismantling the New Deal and taking us back to that Dickensian world of a small, wealthy ruling elite and a large bunch of terrified workers. But I don’t think the average Republican voter has any idea that’s what they are doing.

Guinness: Was the American experiment the first real democracy since Athens?

Hartmann: There were small, semidemocratic areas before the 1600s. The trading blocs in northern Germany and the northern Netherlands, for example, were called the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. But really, the United States was the first major experiment of this type. And the whole world was predicting it would never work. Ten years later, the French tried it with the French Revolution, and it descended into the terrors of Robespierre, and Napoleon rose to power out of that. The French disaster convinced everybody that it was just a matter of time before the U.S. went down too. And then the Civil War happened, and the world held its breath. After our nation survived that conflict, the other countries started to think there might be something to this democracy idea. And we’ve seen a dramatic increase in democracy around the world since then.

Keep in mind, democracy and capitalism are two different things. Democracy is not an economic system. It’s a political system. The conservatives actively promote the idea that democracy and capitalism are the same thing, or that capitalism is a political system. Wherever capitalism is used as a political system, it is a tyranny. It’s rule by the rich. And that’s why it’s important to balance capitalism with democracy, which is what Roosevelt did.

Guinness: So what the neocons in the current administration are trying to impose on Iraq is not so much democracy, but laissez-faire capitalism?

Hartmann: That’s right. In fact, when the neocon ideologues changed the constitution of Iraq, the most radical and dramatic change they made was to install laissez-faire capitalism as the official economic system.

Guinness: Do you think that the conservative agenda is driven by a sincere belief system, or is it just greed disguised as ideology?

Hartmann: I think very few of these people are doing it because they’re greedy. I think the majority of them sleep well at night because they believe they are doing what’s best for the country. Their worldview tells them that this is how to make a stable society.

Guinness: Because the masses can’t be trusted?

Hartmann: Right. John Adams referred to them as the “rabble.” You can’t trust the rabble.

Guinness: So, really, this is a conflict between two views of human nature.

Hartmann: Yes. And God save us from utopianists like the neocons. They’re convinced that we can go over and impose democracy on Iraq and make a better world! [Laughs.] They’re trying to bring back “noblesse oblige,” the idea that those born to royalty have an obligation to help others. It might sound good, but it’s just a justification for inequity. They assume that it’s all right for a tiny upper class to rule a large lower class, provided the rich behave nobly. Thomas Jefferson rejected that notion when he wrote about “Nature’s God” in the Declaration of Independence. He believed that democracy was a part of human nature, something that was burned into us from birth.

Guinness: That’s an intriguing idea. Is there scientific evidence to support it?

Hartmann: Two biologists named Tim Roper and Larissa Conradt at the University of Sussex in Brighton, England, recently did a fascinating study of group decision making in animals. We’ve always assumed that animals are hierarchical in their social structures, that there’s a lead animal who makes decisions for the group. Particularly in mammalian species, there is an alpha male, or in some cases — wolves, for example — an alpha female, and the assumption was that the alpha male or female had absolute control over the group’s actions, like a monarch. But it turns out that’s not true.

Roper and Conradt found that if the herd stops chewing grass and heads to the watering hole, it’s not because the lead animal gave the command. Instead, when 51 percent of the animals start pointing toward the watering hole, the whole herd moves. This is how flocks of birds and schools of fish move, too. And the thresholds vary. When there are predators around, decisions require a super majority: two-thirds have to be pointing toward the watering hole before they move. And this goes across the spectrum in biology, from insects to orangutans. By their actions, the members of the group all “vote,” if you will. Democracy is in our DNA. Jefferson was right.

Guinness: What about the fact that in some species the dominant male has all the mates, and other males don’t have any?

Hartmann: Well, that part is true. The alpha male has first choice of mates, first opportunity for sexual selection. That’s a Darwinian principle, ensuring the transmission of the most competent genetic material. But that individual having the first choice of mates does not translate into that individual having leadership over the pack. The pack is controlled by the majority.

Guinness: Since all other species in nature exhibit democratic behavior, how and when did human beings begin to deviate from that?

Hartmann: There are several theories. Marija Gimbutas, who is now deceased, and her disciple, my friend Riane Eisler, who wrote The Chalice and the Blade, have proposed the nomadic-herder theory, which suggests that when humans began herding animals for food, they became comfortable killing living beings with which they had bonded. In other words, you raise a cow or a goat, and you get to know it — these animals are not that much different from a dog or a cat — and then you kill it and eat it. This coarsened us and led to the domination of men over women, and then of some societies over other societies.

Another theory, which I find particularly fascinating, was first articulated by Walter J. Ong in a book called Orality and Literacy. The idea was picked up by Leonard Shlain, who made it more accessible in his book The Alphabet versus the Goddess. The theory is that when we teach children below the age of seven how to read using abstract alphabets — that is, nonpictographic alphabets, alphabets in which letters are used to form words — it causes the left hemisphere of the brain, which is responsible for abstract thinking, to become ascendant. This changes the way humans think and form societies.

Historically, literacy has always brought in its wake violence and the domination of women. Medieval serf society was far more egalitarian than society during the Victorian era, for example. During the illiterate Middle Ages, Goddess worship was at an all-time high. Mary was worshiped more than Jesus or God. But within a generation or two of the introduction of widespread literacy in Europe, more than a million women were put to death as witches, the worship of the Goddess was suppressed, and the wise women went from being leaders in the community to being looked down upon as crones.

Guinness: Are you suggesting that literacy itself is not necessarily at fault — just that it ought not to be taught too soon?

Hartmann: Right. And I find it interesting that in Sweden, for example, they don’t start teaching children to read until they’re seven. That has also become a tenet of the Waldorf Schools.

In an unregulated, laissez-faire capitalist economy, middle classes don’t normally emerge. . . . What is normal — in our kind of civilization — is to have a small ruling elite and a large number of working poor. Think of the England that Charles Dickens described in A Christmas Carol.

Guinness: Could the degree of democracy in a society be related to its size? In a group of, say, a hundred people, I can have a pretty good sense of whom I’m voting for. But when you’ve got tens of thousands or millions of people, it can’t work the same way.

Hartmann: Jefferson wrote at some length in his letters and in Notes on Virginia about his affection for the ward system. He believed that the only way democracy could work over the long term was if local wards and precincts remained politically vital. When you get more than a few hundred people making decisions, the sociopaths among us can take over, and the special interests gain power. The bulwark against this is local participation. Democracy has to go from the smallest unit to the largest, rather than from the individual directly to the national level.

Scientists have found a correlation between the size of a primate’s neocortex and the size of social institutions in that species. Primates with larger neocortices live in larger social groups. By this calculation, humans should have an average community size of 150 people. And there’s a long history of support for this. Indigenous tribal peoples around the world never have local political units larger than 150 people. They will split into separate clans at that point. When Joseph Smith started the Mormon religion out west, he said that whenever a community got larger than 150 people, it had to split up. The kibbutzim in Israel are all smaller than a few hundred people.

This problem of scale is one reason why we have government regulatory agencies. I live in a town of nine thousand people in Vermont, and if there’s a restaurant that’s serving unsafe food, or a doctor in town who is incompetent, the word spreads fairly quickly. But in New York City, that unsafe restaurant or that bad doctor could stay in business indefinitely. To deal with this, we formed the Food and Drug Administration and other regulatory agencies that oversee public health and sanitation, because in larger communities it isn’t possible for people to be forewarned the old-fashioned way.

Guinness: You’ve said that, for Thomas Jefferson, democracy was more than just the most efficient or effective form of government. It actually had something to do with spirituality and the evolution of humankind.

Hartmann: Jefferson, like most of the Founders, was a deist. Deists believed in God, but rejected religious authority and favored a rational understanding of the universe. Over time the deists turned into the Unitarians.

Deism arose in reaction to the Puritans, who had set up a theocracy in Massachusetts in the late seventeenth century. Public hanging of “witches” on the Boston Common was a fairly ordinary event. So Jefferson and others like him were struggling with these questions: Is God a Puritan warlord to be appeased, or could there be some other form of intelligence that brought the universe into being? And must humans always live in fear of a tyrant’s wrath? Is that the only bond that holds society together?

There’s a strong effort by the modern-day Puritans, the Christian fundamentalists, to rewrite history to suggest that the Founders were Puritans. But in fact, the Founders were deists and Freemasons and mystics who went out of their way to distance themselves from the Puritans. The Founders believed it was good to question both political and spiritual “truths,” and to create a government that was receptive to change and capable of embracing a wide variety of views without any of those views becoming dominant. As George Washington said, “I hope that we shall ever be more liberal.” The Puritans may have been among the earliest settlers of this nation, but they did not create our Constitution and our form of government, as Jerry Falwell would like us to believe.

There are actually phony quotes from the Founders on the Internet about how deeply Christian they were. These quotes have been made up out of whole cloth. David Barton, a fundamentalist activist and former vice-chairman of the Texas GOP, created most of them. There are entire websites devoted to debunking him, but he’s a significant character in the Christian home-schooling movement. The phony quotes are repeated in Christian textbooks. A member of Congress has even read some of them into the Congressional Record.

Guinness: How did your personal spiritual quest lead to your study of history and politics?

Hartmann: It isn’t as if I made a transition from spirituality to politics. I’ve never abandoned spirituality, and there has never been a time in my life when I was not interested in politics. Even when I was teaching meditation, my purpose was always to understand how we can make life better for all of us. In the sixties, I was very active in the antiwar movement and the civil-rights movement. I’ve always seen religion and politics as threads in the same fabric.

You often see this conflation of religion and politics on the Right, but frankly, it’s always been there on the Left, too. The Right promotes the stereotype that the people involved in liberal and progressive politics are mainly Jewish. In fact, they imply this in an anti-Semitic fashion. But a whole spectrum of people with deeply held spiritual beliefs — including Protestants, Catholics, mystics, and others — are involved in progressive politics. The Right has tried to mischaracterize the spirituality of the Left just as they’ve tried to mischaracterize the spirituality of the Founders.

There’s a strong effort by the modern-day Puritans, the Christian fundamentalists, to rewrite history to suggest that the Founders were Puritans. But in fact, the Founders . . . believed it was good to question both political and spiritual “truths.”

Guinness: How did the Founders come up with the design for our democratic institutions? What precedents did they study? Where did they get their inspiration?

Hartmann: There were a number of sources that informed them. Probably one of the greatest influences, particularly on Jefferson, was Paul de Rapin-Thoyras’s History of England. Rapin has been out of print since the late 1700s, but Jefferson believed him to be the greatest historian of England, as did Adams. In his History of England, Rapin suggested that after the Romans left in the 400s — and before the French invaded in 1066 and set up the modern-day lineage of the kings and queens of England — the British Isles reverted back to the egalitarian, democratic form of government that they’d had prior to the Roman invasion.

Jefferson was absolutely enamored of that idea. Some modern historians make fun of him for it, and I think that’s a shame. I went back and read Rapin’s History of England, and it’s really quite startling, because the society he describes is not all that different from the societies among the Native Americans. Rapin says there were hundreds of “kings” of England from 400 to 1066, and that really these kings were local community leaders, and that kingship was more an obligation than an opportunity for self-aggrandizement or the accumulation of wealth or power. What he describes, basically, is a tribal system in which each tribe would elect representatives who would go to the national councils. They called this the “witenagemot,” or “assembly of wise men,” and it was very similar to what the Native Americans did.

The Native Americans, of course, were a major influence on the Founders. They influenced Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, who helped shape the Constitution probably more than any other person. Franklin and Jefferson, in particular, had long and deep relations with native peoples. Much of the United States Constitution was borrowed from either the Iroquois Confederacy or the Saxon forms of government outlined by Rapin.

Guinness: One aspect of our Constitution that puzzles me is that the electoral-college system seems to strongly encourage a two-party system. Why did the Founders set it up this way?

Hartmann: Well, at the time they didn’t know there might be a better option. And they saw that, in a winner-take-all election with more than two political parties, you would likely end up with a minority of voters electing the president, which was not democratic. For example, if there are three candidates, one could win with only 34 percent of the vote.

It wasn’t until 1861 that John Stuart Mill first proposed proportional representation, which has been adopted by almost all of the democracies in the world. In a proportional election, you vote for a party, and if that party gets 30 percent of the vote, then it gets 30 percent of the seats in the legislature. Then the representatives in the legislature get together and elect the prime minister.

Another solution is instant-runoff voting, in which voters rank the candidates in order of preference: 1, 2, 3, and so on. The candidate with the fewest “number 1” votes is eliminated, and his or her ballots go to whoever received the “number 2” vote on them. This continues until one candidate receives a majority. Australia and New Zealand already use instant-runoff voting, and we need to adopt it here, starting at the local level, because a change like this has to come from the ground up.

The electoral-college system was also designed to overcome the logistical difficulty of a national election in the eighteenth century. It was impossible then for people in Georgia, for example, to get to know a candidate in Virginia or Massachusetts. So each state would elect its wisest elders, and those elders would join with the elders of other states to evaluate the candidates for president. And this council of wise elders would then elect our head of state: thus, the electoral college.

As chief justice of the Supreme Court William Rehnquist pointed out in Bush v. Gore, the Constitution does not grant the people of the United States the right to vote for president. We don’t even have a constitutional right to vote for the electors. The states can choose the electors any way they want.

Guinness: To use an analogy from computer technology, it sounds like we are still using Democracy 1.0.

Hartmann: Yes, and other modern democracies are up to version 3.4.

Guinness: Do you think we should abolish the electoral college?

Hartmann: I’m not yet convinced that we should, because the electoral college also gives small states a say in presidential elections. You see, the number of electoral votes a state has is equal to its number of representatives in Congress, and since every state has at least two senators and one representative in the House, every state has at least three electoral votes. If you abolish the electoral college, then a presidential campaign conceivably could be run in a handful of the most-populous states, and the rest of the country would be ignored. I’m not convinced that giving a little extra weight to smaller states is always a good thing, but I’m not convinced it’s so evil that we have to amend the Constitution to get rid of it.

One change that I would make to the electoral college is to have more states follow Maine’s lead and choose their electors proportionately based on the vote in the state, rather than have it be a winner-take-all. If we had that system, then our national elections would be much more democratic.

Guinness: But it’s up to each state to decide whether to do that or not.

Hartmann: That’s correct. They tried to switch to a proportional system in Colorado this time around, and the Republicans fought it, because they thought that the state was going to go Republican and they wanted all its electoral- college votes. Had the Democrats been ascendant, they probably would have fought it too. I think it’s important that we put democracy above partisan loyalties, even when it may hurt our own party over the short term, because over the long term it will be better for our nation.

Guinness: Do you have any advice for people who feel overwhelmed and powerless in the face of today’s political and social challenges?

Hartmann: My advice to them is to join something. Join the local chapter of their political party. Here in Montpelier there are dozens of groups that get together once a month to study books and talk politics. However you do it, get together with other people. Connect. That’s what society is about.

Guinness: You’ve pointed out that corporations and the Right have been very effective in using media control to shape public debate. Where can we go for an alternative point of view?

Hartmann: The Internet is filling the gap with websites like BuzzFlash.com and CommonDreams.org and OpEdNews.com and Truthout.com and so on. We’re also seeing the rise of liberal talk radio, although an awful lot of it seems like people sitting around making jokes and complaining rather than getting into these issues in some depth and waking people up. But I’m hopeful. We have to tell the truth — because the truth really is on our side. The conservatives are acting on the mistaken beliefs that (1) people are evil and need to be controlled, and (2) democracy doesn’t work, and therefore an aristocracy — or at least a meritocracy — must rule. This is the same argument Alexander Hamilton and John Adams were making back in the 1780s. It wasn’t right then, and it’s not right now.