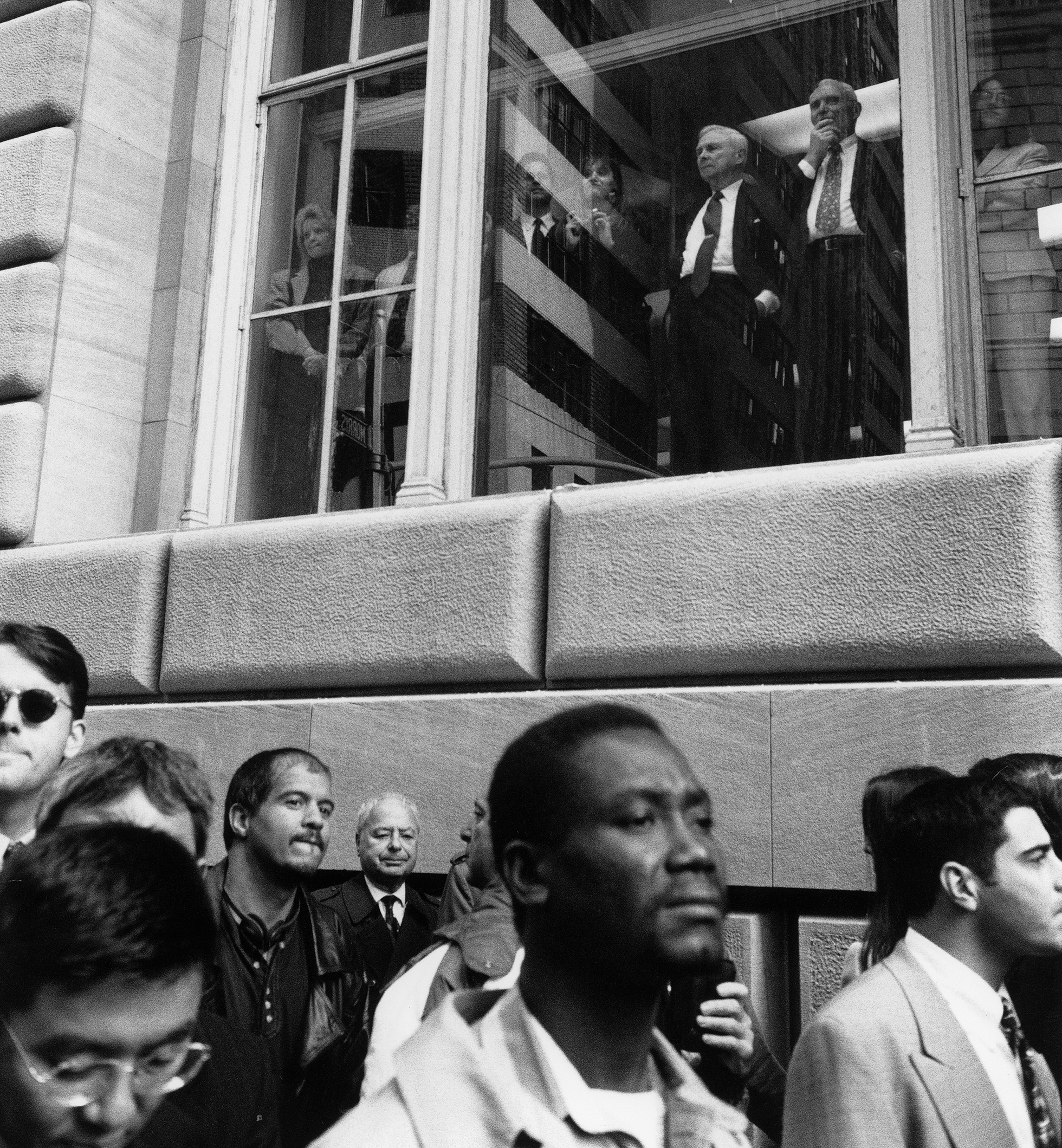

In his forty-year career as a social-justice activist, Tom Hayden has served jail time, and he has served as a California state senator. Arrested in 1968 for “inciting a riot” outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, he returned to that city sixteen years later as a delegate to the convention. On a given weekend Hayden might spend one day participating in a street demonstration and the next addressing a roomful of elected officials.

In the sixties and seventies Hayden was active in the civil-rights and antiwar movements. He was a founding member of Students for a Democratic Society and principal author of the landmark Port Huron Statement, which called for a radical shift toward participatory democracy, granting citizens a more direct hand in governance. As a “freedom rider,” he rode buses in the South to protest segregation and racism. He was also a vocal critic of the Vietnam War, flying on several occasions to Cambodia and North Vietnam to assess avenues for a peaceful solution to the conflict. After his 1968 arrest outside the Democratic National Convention, Hayden was tried on conspiracy charges alongside seven other activists. Known as the “Chicago Eight,” the defendants became a symbol of sixties student protest. All were exonerated.

In the 1980s Hayden’s activism took a new trajectory. With the election of Ronald Reagan as president and the ascendancy of the Republican Party, Hayden decided to try his hand at state politics. His election to the California State Assembly in 1982 so upset Republican representatives that they twice tried unsuccessfully to block his seating, citing his long-ago trips to North Vietnam. Hayden went on to serve five consecutive terms as a California assemblyman and two terms as a California state senator. In those eighteen years Hayden ushered through cutting-edge legislation on the environment, education, prison reform, women’s issues, and campaign-finance reform. At the end of his second and final term as senator, the Los Angeles Times reported, Hayden received the longest farewell ovation of any legislator in memory.

Since then Hayden has focused on writing and teaching. To date he has authored eleven books on subjects ranging from environmentalism, to gangs, to his own Irish American heritage. Rebel (Red Hen Press), his memoir of his experiences in the sixties, is widely used in high-school and college classrooms. Hayden is currently a visiting professor at the Urban and Environmental Policy Institute at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and also serves as a social-studies counselor at several inner-city public high schools.

Though retired from state politics, Hayden remains a bellwether of the social-justice movement; to find where the “edge” is, look to what Hayden is talking about. These days he serves as national codirector of No More Sweatshops, which urges the government to hold corporations accountable for their labor practices. He also speaks out against the global agenda of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and works with former gang members to reduce street violence.

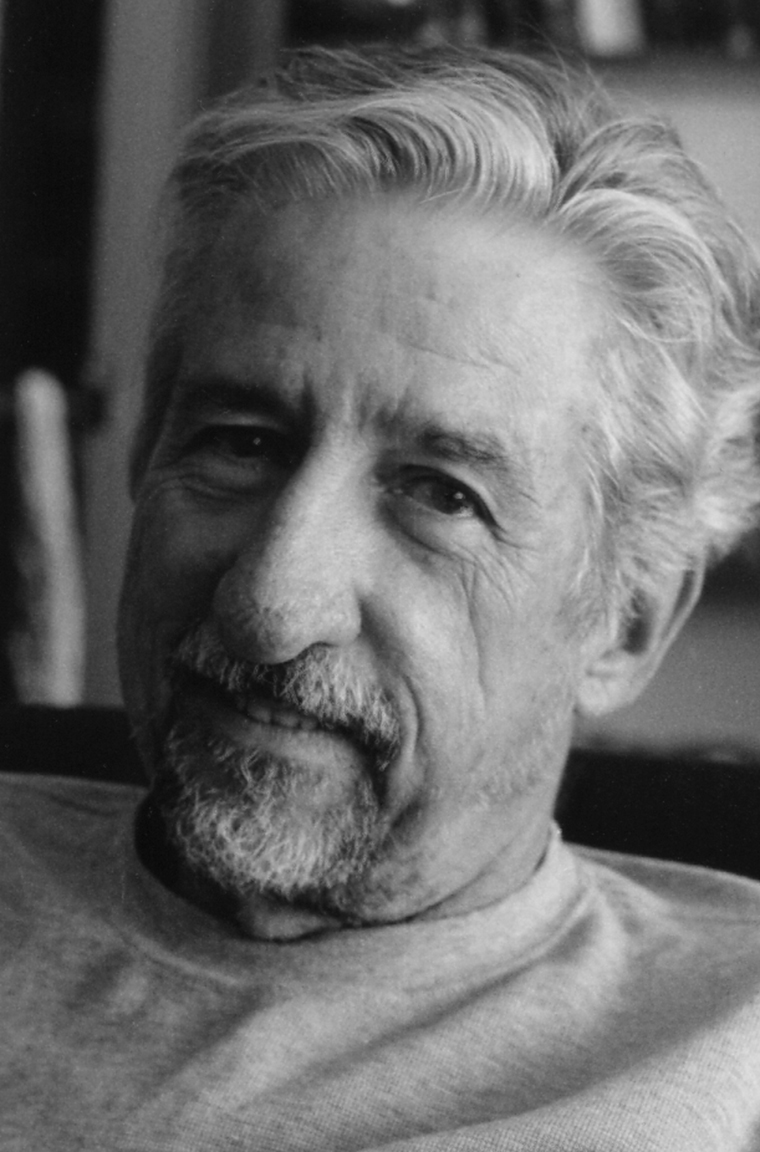

Hayden lives in Los Angeles with his wife, singer and actress Barbara Williams, and their four-year-old son, Liam. He also has two adult children from a previous marriage to actress Jane Fonda. When we met for this interview some months ago, Hayden invited me to his modest canyon home, where we talked in his office for most of a Sunday afternoon. On several occasions Liam poked his head into the office looking for his father, who stopped the interview to play with his son. After each break Hayden picked up exactly where we’d left off, the conversation still fresh in his mind.

TOM HAYDEN

© Anna Blackshaw

McKee: It’s been forty years since the Port Huron Statement called for a more participatory democracy. Is our society today more or less democratic than it was then?

Hayden: U.S. history as a whole is an ongoing struggle between growing participatory democracy, on the one hand, and the attempts of the corporate state to absorb and contain that democracy, on the other. Over the past 250 years, the corporate state has had to contend with Tom Paine’s Rights of Man, Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman, the women’s-suffrage movement, the abolition of slavery and the Negro-suffrage movement, the labor movement, the social upheaval of the 1960s, and the environmental movement. Ultimately the corporate state absorbs and accepts these movements (though it might take a hundred years) while trying to limit their effect on capitalism and elite rule.

So we have greater participation in the democratic process than we did forty years ago, or a hundred years ago, yet the elites are ever more intent on escaping its constrictions. For example, after the Vietnam War, there was a widespread desire to rein in, if not do away with, the CIA — certainly, to stop the intelligence services from assassinating foreign leaders. And there was an attempt to bring the presidency under control through, among other things, the passage of the Freedom of Information Act, which requires the disclosure of some secrets that presidents like to keep in the name of “national security.” These were all significant accomplishments, providing greater protections than exist in many other countries, including the United Kingdom. But secrecy has taken up another address since then. Elements of the CIA now seem to be secret unto themselves, and the Pentagon has developed its own intelligence network and spying capacity. I think of these powerful elites as being on the run; others think that they’re wielding more power over us than ever. Whatever the case, I think we have to fight all the time to keep participatory democracy the norm.

McKee: Can corporations ever be made to accept this norm?

Hayden: Growing up, I thought they had accepted it. In the fifties and sixties most working-class people were members of unions, and we were taught that there was a kind of balance — between labor and management; between different branches of government — and that no one institution had power over the others.

Now, however, we’re in a phase in which corporations are trying to burst the fetters of the welfare state and the New Deal and the sixties reforms, and it makes me more inclined to believe that they have an inherent unwillingness to coexist with democracy and will always try to do away with it. I think this started in 1972 with the formation of the Business Roundtable, which aimed to roll back consumer protections, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, environmental restrictions, the women’s movement — all forces that were pressuring corporations to broaden access and yield on property rights. The corporations have pursued this agenda indirectly, which shows that they’re nervous about their own legitimacy. Attempts to roll back air-pollution regulations are always called something like the “Blue Skies Act.” The fact that this subterfuge is necessary demonstrates that the populace is more supportive of environmental regulation than it might appear.

Nevertheless, corporations engage in a permanent battle against any democratic controls over their freedom of action. They’ve internationalized their private agenda in the WTO, which attempts to impose the will of corporations on the globe through the prohibition of reforms and the creation of an unregulated global market. Corporations then turn to U.S. politicians and argue that any attempt to protect the public interest makes this country less competitive, and that our economy will go down if we don’t conform to international rules of trade.

McKee: Which side do you think will prevail?

Hayden: I don’t think there’s any assurance as to how things will turn out, but I’ve always believed that the action we take, successful or not, reminds people that progress is possible. If we don’t take action, we give the appearance that it’s impossible to change things. Any action, while not guaranteeing change, creates possibilities that weren’t there before.

McKee: Why has liberal become a dirty word?

Hayden: Liberal sociological thinking has been in retreat since the Reagan presidency. Around the late seventies, you could feel the political middle shifting to the right. The joke at the time was: “A liberal is someone who hasn’t been mugged yet.” Residential burglary was on the rise, and all the attendant rhetoric about drugs and youth crime was affecting middle-of-the-road voters, making them more security-conscious. They were buying locks for their homes and lighting for their driveways. Republicans exploited this situation by proclaiming that there was no time to address underlying causes; we had to have more police on the street, because the enemy was at your doorstep and selling drugs outside your kids’ school.

Politically — and I emphasize politically, apart from other standards of truth — most Democrats had no answer for this. I had no answer for it, because I was getting hit by crime in my own neighborhood. I had several burglaries at my house, and the argument for having more police on the street was a tempting one. In my mind, however, there was no contradiction between having an immediate deterrent and at the same time working on the underlying causes. What I didn’t realize then was that there would never come a time when the underlying causes would be addressed. “Law and order,” in the Republican mind, is simply a matter of more police and more prisons.

In the late seventies the conservatives put forward the theory that there are no root causes for crime, and they’ve spent almost thirty years now trying to demolish all arguments for rehabilitation and instead promote the idea that there exists a class of “superpredators” or “career criminals,” incorrigibles who can be dealt with only by suppression. And that idea has taken hold.

The superpredator theory allows conservatives and Republicans to avoid the charge of racism. They can say, “We have our Colin Powells and our Condoleezza Rices; we’re not talking about excluding the vast majority of law-abiding people of color. We’re talking instead about the superpredators, many of whom happen to be black. But we’re not judging them by their skin color; we’re judging them by the crimes they commit” — by the “content of their character,” to borrow Martin Luther King Jr.’s phrase, which has now been co-opted by conservatives.

Meanwhile, the same rationale justifies our having more people in prison per capita than any other country in the world. The numbers are staggering. On any given day, there are around 2 million people in prison in this country. But that number tells only part of the story. Nobody — and this is an example of where we’re not directing our attention — has done the math on how many ex-convicts there are on the streets. That number is not 2 million, but a huge multiple of that.

In this political climate, police budgets in most cities are sacrosanct or are increasing, while federal funding for social programs has declined. As a result, there are no discretionary funds available for affordable housing, mental-health facilities, healthcare — all things that are vital to the rehabilitation of criminals. Of course, conservatives say rehabilitation is a waste of money anyway. But the fact is that being “tough on crime” isn’t working. Although we have the largest percentage of our people in prison, and the most rapid expansion of the police force, we still have the highest homicide rate among the world’s richest nations, and there’s no end in sight.

Just as hostility toward people of color and the fear of crime are turning our suburbs into gated fortresses, the so-called war on terror is turning the country as a whole into a fortress against much of the rest of the world. This is not a defense against terrorism; it’s part of the framework in which terrorism arises. But that framework is not discussed. Terrorism is said to be a result of “evil,” rather than a symptom of profound dislocation.

We have greater participation in the democratic process than we did forty years ago, or a hundred years ago, yet the elites are ever more intent on escaping its constrictions.

McKee: So you think our government is making the same mistakes in response to terrorism as it has in response to crime?

Hayden: Yes. I think we have a collective need to find a scapegoat, an enemy. The gang member is the domestic version, and the terrorist is the international version. Before 9/11 it was the narcoterrorists, and before that the communists. The trick here is to identify the enemy as a terrorist, or a superpredator, as opposed to a person who commits an act of terror or crime. If they are “terrorists,” then war is the only remedy. But if they are people who commit acts of terror under certain conditions, then you can eliminate the conditions that give rise to the terrorism.

Let’s look at suicide bombers. Suicide bombers were not prevalent in the Middle East during the first Palestinian intifada. The number of suicide bombings increased drastically in the 1990s. That pattern would lead one to believe that suicide bombings are not the result of certain people’s desire for martyrdom, but rather of something that happened in the early nineties, a catalyst that drove Palestinians to desperation. But that line of inquiry is foreclosed by the neoconservative presumptions that now hold sway. In the eyes of the neocons, who are more hawkish and aggressive than their predecessors on the Right, it’s as if suicide bombings have always occurred, as if the “suicide bomber” were a permanent type of person, as opposed to a person who, in desperate circumstances, became a suicide bomber.

The discrepancy between the facts and the neoconservative ideology is equally fantastic for superpredators. A decade ago the neocon argument was that, because there were going to be more minority teenagers due to population trends, there were going to be more violent criminals. It’s an argument based on the dubious idea that a certain percentage of people are destined at birth to become violent criminals. As it happened, however, more teenagers did not translate into a crime wave. So the crime rate must depend on other variables besides how many black and brown babies are born. What an insight!

Nevertheless, a pernicious new form of racism has taken hold here, completely infecting the body politic. The superpredator theory remains the given reason for why we have these so-called special-housing units — really maximum-security lockups — at virtually every prison, including juvenile facilities. It is the belief that “these people” are all inherently explosive; that none of them can be reached or reformed.

As a progressive, I believe that people can, in fact, be diverted away from violent crime or terrorism by being given jobs, education, and, most importantly, respect. But there are not resources available to pursue both our current approach and one that addresses underlying causes. So any brave soul who wants to question the framework of the war on terrorism will get only token resources, at best, to carry out an alternative vision. It’s no wonder that few are willing to make the case.

The situation is similar, in a way, to what we faced during the Cold War, which gripped our politics for forty years. Back then, there wasn’t enough money for both more nuclear weapons and troops, on the one hand, and housing and jobs at home, on the other. And if you questioned the overall Cold War framework, as Martin Luther King Jr. did in 1967 by linking poverty to the Vietnam War, your patriotism — and even your sanity — was questioned.

McKee: What was your experience in the California legislature when you tried to step outside the framework and look at root causes?

Hayden: I found that through persistent advocacy, I could educate the Senate and sometimes get the votes to pass concrete proposals. For instance, one of the most practical means of steering former gang members toward jobs is to offer free tattoo removal. So I got a million dollars into the budget for tattoo removal. It appealed to religious conservatives, who think that tattoos are the mark of the devil, and liberals were easily persuaded that these kids needed to get the tattoos off their faces and hands if they were to have a chance at getting jobs. But the liberals would support tattoo removal only if the conservatives did, too. That way they couldn’t be attacked for being “soft on gangs.”

I made headway on rehabilitation in the juvenile facilities and state prisons by arguing that, if we rehabilitated 10 percent of the inmates in California prisons, it would save taxpayers $400 million. Very few legislators were willing to argue that you couldn’t rehabilitate even 10 percent. They were not completely in the grip of the superpredator notion.

In addition I found that bringing former gang members to the legislature to testify scored points, because once you meet people face to face, you have to acknowledge their humanity. Afterward the legislature passed a bill to allow former gang members to participate in a round-table discussion on gang violence. Yet, even though their advisors supported it, both Democratic and Republican governors vetoed the bill for political reasons: they did not want to be held accountable for having allowed a former gang member to influence policy-making.

So you see how difficult it is to pursue rehabilitation. If nobody will hire or appoint a former gang member, then all we’re really doing is keeping them in limbo until they are back in the prison system.

My work on these issues in the legislature was all worthwhile, but it started with me and ended with me. It takes somebody with very strong beliefs to tackle an issue where there are no campaign contributors or voter constituencies on your side.

I think it’s helpful to remind white ethnics that they, too, came here in boats; that they, too, lived in slums; . . . that everything that was said about them in those days is now being said about Salvadorans, Dominicans, African Americans, Mexicans, Vietnamese, and Cambodians in our inner cities.

McKee: In your book Street Wars, you write, “Until America’s white ethnics get their true story straight, they will be unable to understand, face, and help in healing the wounds of today’s inner-city youth.” What do you mean?

Hayden: The true story is that the Jews, the Italians, and the Irish — not to mention the Germans and others — all went through a phase in this country of being an underclass that produced violent street gangs. It’s remembered occasionally in movies like Gangs of New York, for example, but those are fictional representations given to fantasy and nostalgia. There seems to be virtually no memory among today’s white ethnics of the times when they experienced ethnic profiling and police suppression, and of how they became working-class and middle-class through government intervention during the New Deal. That truth has been replaced with the myth that each immigrant family fought its way into the middle class alone. Collective struggle is almost entirely missing from our national immigrant myth. The psychological reason for this is that people don’t want to admit that they might have acquired a better life through anything other than their own hard work. Their pride won’t let them admit to getting a hand up from the government or the labor movement.

I think it’s helpful to remind white ethnics that they, too, came here in boats; that they, too, lived in slums; that they, too, had yellow fever; that they, too, were stigmatized as incorrigible; that they, too, had the highest homicide rates and the highest incarceration rates and the highest rates of mental illness; and that everything that was said about them in those days is now being said about Salvadorans, Dominicans, African Americans, Mexicans, Vietnamese, and Cambodians in our inner cities.

The question I haven’t resolved is whether race is even more essential to success than collective struggle and government programs. In other words, did these previous generations of gangsters become assimilated because they were white? Is the real difference that the existing white majority will resist the assimilation of any nonwhite minority?

McKee: The Port Huron Statement spoke powerfully of how the government used the fear of communism to justify huge military budgets, the curtailment of civil liberties at home, and the manipulation of truth. Do you see parallels between the Cold War against communism and today’s war on terror?

Hayden: Yes, there are parallels, but today the abuses are even worse. When the Soviet Union and China exploded their nuclear bombs, we didn’t invade them. Yet we invaded Iraq on the theory that Saddam Hussein might have been developing a bomb. I think we’re in more-dangerous hands now than we were during the Cold War. It’s as if Joe McCarthy, the infamous red-baiting senator of the 1950s, has become secretary of defense.

McKee: What fuels our country’s quest for empire?

Hayden: I have no easy answer for that question. Sometimes I think it’s the capitalist market’s need to expand. It’s like a shark: by its nature it must constantly feed. It’s not just a matter of a few greedy people. I’m talking about the market itself being insatiable and hostile to regulation and control. But just as they succeeded in avoiding the charge of being racists, the Republicans have succeeded in avoiding the charge that they are greedy capitalists by speaking of “small business” and “market solutions.” They don’t generally get out there and speak unapologetically in favor of more capitalism.

The word that they’ve deceived the public with the most is growth, which always sounds appealing. Progressives have to establish a quality-of-life index that challenges the gross national product as a measure of how we’re doing as a society. It’s not a question of growth versus no growth; it’s which type of growth do you prefer: growth in prenatal care, or growth in the number of AK-47s on the street? This is an ideological battle that the Left has to win.

I think the capitalist expansion framework is rooted in the frontier history of this country. Historian William Appleman Williams believes the frontier functioned as a safety valve for domestic conflict. For example, in the early days of the nation, landless farmers threatened to rise up against aristocrats and large property owners. So the farmers were offered land grants if they became frontiersmen and fought the Indians, and the conflict was defused rather than settled. Similarly, the question of whether the United States was going to become a social-democratic country or a purely capitalist one wasn’t debated very long, because the Appalachian frontier and the Ohio Valley were the solutions; and after that, the Great Plains and California.

This history, I think, makes us the staunchest of the capitalist countries. In Western Europe, for example, the models of capitalism at work are much more benign, perhaps because those countries haven’t been able to expand. The European Left created social-democratic parties and unions, so European workers have longer vacations, better healthcare programs, and higher workplace-safety standards. In Western Europe and Canada capitalism coexists with a proactive government that represents consumers, workers, and the public interest.

McKee: Why has that not happened here?

Hayden: Again, I have no simple answer, except that we seem more aggressive in this country, which might have something to do with our relative youth as a nation. Europeans have had more experience with being empires. Germany, France, and Italy, among others, have demonstrated that there can be life after empire. They don’t seem as agitated about the loss of power as America is.

Now, the neocons would say that’s because our military budget defends Europe, too, but I don’t think there’s any evidence that European countries feel protected by the U.S. colossus. I think they’ve realized, painfully, that no one stays number one forever, that empires come and go, but you can still have a good life even if you’re not the empire. U.S. politicians dare not utter this sentiment. How could one argue that we should be less competitive? And so our politicians try to have it both ways: “We don’t want an empire,” they say. “We just want to be the best; we want to have a competitive edge.” Well, what does it mean to have a “competitive edge” in technology or education or warfare, except to put the rest of the world at a disadvantage? But Americans blindly buy into the idea of competition and move forward with the quest for dominance. The idea of peaceful coexistence has never prevailed here, except temporarily during the Cold War, and then only because the Soviet Union and China had the Bomb.

If the Quakers had had their way in colonial times, we could have had peaceful coexistence with the Native Americans. There were attempts to create an Indian state. Can you imagine the thirteen colonies adding a fourteenth, Indian state? There were other attempts throughout history, but the voices for coexistence were just drowned out.

The dominant religion in the United States today is an expansionist Christianity. The theologian and activist Cornel West calls it the “Constantinian model” of Christianity, after the Roman emperor Constantine, who converted to the Christian faith and made it the official state religion of the Roman Empire. The social order was turned on its head, as a formerly persecuted religious minority was now a powerful political force.

Similarly, we’re seeing the ascendancy of a bizarre, populist Christianity that’s pro-state and pro-corporation. There was a time during the civil-rights movement when Christianity was not allied with the U.S. government. Nor was it an ally of the state in the previous century, when a large number of Christians from the prophetic tradition started the abolitionist movement. They attacked the citadels of power, motivated by a moral fervor. But now the moral fervor has been applied to the cause of cutting taxes on the rich!

McKee: You write in many of your books about the power of personal transformation: gang members becoming peacemakers, your own shifts in consciousness. How does personal transformation relate to the larger, societal shifts?

Hayden: You can’t bring about justice without personal transformation. The effort to abolish sweatshop labor, for example, has to arise from a personal disgust with sweatshops.

This idea can be taken too far, though. There are many people who believe that we have to achieve individual transformation before we can even begin to work for social change. I think that’s too dualistic. The process of social change can be helped along by a person’s actions, even if he or she hasn’t changed entirely on a personal level.

I understand why people put personal transformation first, however. They’re reacting to a tradition that has always said, “Objective conditions have to change first; people change later.” The problem with that view is the idea that there are objective conditions, when in reality they’re in the eye of the beholder. For instance, the American Revolution happened because sufficient numbers of colonists stopped seeing themselves as British subjects and started seeing themselves as independent citizens. Before slavery could be dismantled as an institution, people had to stop seeing it as an objective condition. And the fight for American women to vote began when Abigail Adams told her husband, John, the future second president of this country, that she would never accept a social order in which women had no voice in the making of laws. “There will be a rebellion,” she said. That was in 1775 or 1776. It took 140 years, but once women became conscious that they were not satellites of men, it was inevitable that they would win the vote.

So change begins in the individual lives of countless people when they no longer accept existing conditions as inevitable. But you can’t just change consciousness and expect that institutions will follow. They’ve got to be overthrown, replaced, altered. You have to have both elements. I don’t know why it’s so hard to grasp this, but people seem to come down forcibly on one side or the other. “I am a card-carrying member of the Natural Resources Defense Council; do not tell me that I have to give up my SUV!” — people actually say that. Other people say we’ve all got to ride bicycles to work before the U.S. can comply with the Kyoto Protocol. The truth lies somewhere in between.

McKee: What happens when supposed “incorrigibles” change their consciousness?

Hayden: I’ve seen plenty of gang members change their lives and get almost no respect, recognition, or resources in return. They seem to be permanent scapegoats. I understand that some of the reason for this is practical; it’s hard, for instance, to get an employer to hire somebody with gang tattoos. But I see no reason why felons who’ve served their time should be prevented from voting. They shouldn’t remain scapegoats their whole lives.

I’ve known people who did terrible, even inhuman, things, but later were transformed. One Mexican man I’ve known since he was a teenager was raised to hate blacks as well as whites. He used to get pleasure out of robbing people; it gave him a sense of dignity, he said, to see them down on their knees. He got stabbed when he was seventeen years old and would have bled to death had he not been rushed to the hospital. When he woke up, he saw looking down at him the African American doctor who had saved him. That was at least fifteen years ago, and he’s never been the same since. He stayed in his neighborhood and works to channel kids away from gangs. He now gets along with people of all races.

The root social causes of violence are poverty, discrimination, dislocation, marginalization, and the like, and any policies that perpetuate those conditions will increase people’s propensity for violence. But poverty is not the final trigger for violence, because not all poor people are violent. Rather, the final trigger for violence is shame. Poverty is shameful in this country, and it’s the shame and humiliation some poor people feel that makes them violent; if they don’t have therapy, books, and higher education, then they have no way to siphon it off. They live their whole lives in a context of traumatic shame. So any policies that lessen this shame will also lessen violence and make positive social transformation more likely.

Christians from the prophetic tradition started the abolitionist movement. They attacked the citadels of power, motivated by a moral fervor. But now the moral fervor has been applied to the cause of cutting taxes on the rich!

McKee: You suffered a heart failure in 2001. Did you experience any personal transformation as a result?

Hayden: It certainly introduced me to the way the ego can play tricks on us. The ego’s primary purpose is to try to escape mortality. It’s not subject to moral controls or upbringing. Even though I’d spent the greater part of my life thinking about the cycles of life and death, I couldn’t control my ego’s desire to be immortal.

Before my heart failure, I was living a hyperkinetic lifestyle: eating whenever I could, avoiding any relaxation, violating all the rules of good health in order to get as much done as possible, and generally acting as if my body could take that sort of abuse forever. But my body couldn’t take it anymore. At sixty-one I was forced to realize — and I wish I had realized this long before — that I was getting old.

I decided to stop trying to run things and instead do more reflecting and researching and writing. Being a political leader, as important as it may be, only gave me a burning feeling in my chest. It requires too many hours a day, too many days a week. It’s a job for people whose hearts can take it. Besides, nobody can lead forever. Now I spend more time tracking the rise of new social movements, teaching about the history of protest, and coming to some conclusions.

My adopted son Liam was one year old when I had heart failure. I’d known I was taking a risk, adopting a child late in life. My health crisis made me even more conscious that I’ve got to be a father to a little boy. I can only hope that, with proper diet and exercise, I can live another twenty or thirty years. But I try to remember that the time I have with Liam today may be the only time that I have with him.