for Todd Laufenberg

At midnight I slipped into my bleach-stained Levi’s and rubber gloves and walked across the street from my apartment to city hall, where I worked as a janitor. One of the offices upstairs was haunted, and the moment I entered that austere room with the branching shadows of the great elm wavering in the window, I was shot through with a rattling fear. I always cleaned that office first, frequently neglecting to vacuum. The rest of the building I did on automatic pilot: filling mop bucket, emptying metal tampon box, rubbing fingerprints off mirrors, vacuuming up the dust of ennui, and squeaking my cart around in the magnificent, ghostly silence. I finished at four or five in the morning, then went home and sat for a while in my swivel chair (rusted by two floods) with cigarettes and a spaghetti-sauce jar of cheap red wine. With the morning sunlight barely touching the curtains in my tiny basement room, I slept.

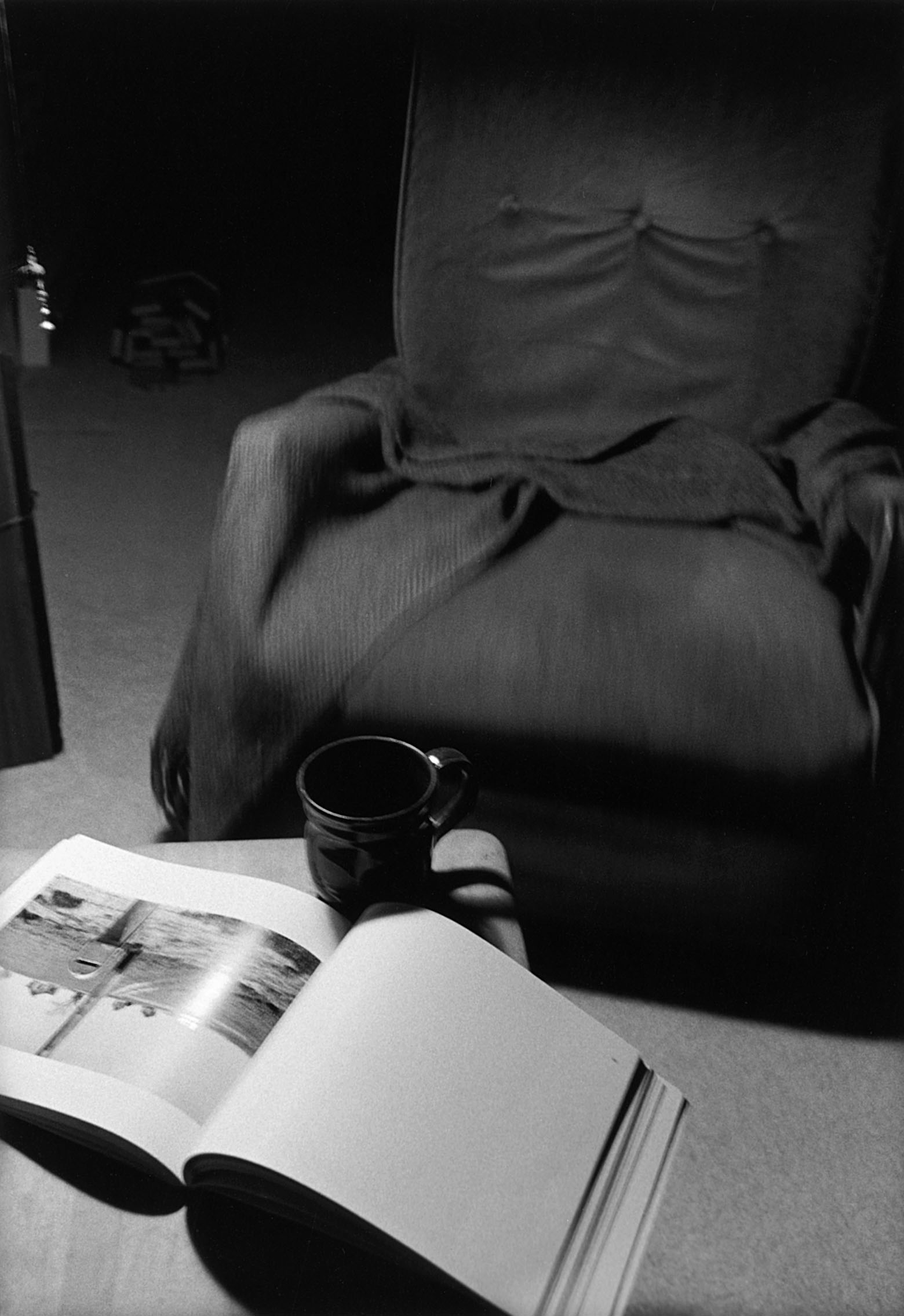

I wrote as soon as I got up, moving the five feet from bed to table: hat, coveralls, and cup of tea if it was cold. Friends sometimes stopped by in the afternoons and then left me with the rest of the day to fill. Time moved a little slower in the daylight. It was always easier after the sun went down. I listened to the radio and read books. The Fareway next door to my apartment complex sold roasted chickens for three bucks.

On Saturday nights I walked up to the university and read my stories at an open mike sponsored by the creative-writing department. I was thirty-seven and had been a returning student until I’d dropped out a few months before. The open mikes were the only reason I’d stayed in this small Iowa town — them and the friends I had made and my guilt over the enormous energy I had wasted, which hovered all around me every waking moment like a city-hall ghost. I usually read fifth or seventh or ninth behind the scheduled readers: the black student who wrote of the difficulty of being black, the homosexual student who wrote of the difficulty of being homosexual, the adopted student, the overweight student, and so on. It was a difficult time in America. So-called literature had become a grumbling pole, and it was no wonder people stayed home and watched television instead of buying books or coming to open mikes.

One night I read a short, autobiographical story about how difficult it was being a B-movie zombie. Afterward a few people I didn’t know came over to my table, the most interesting of whom was an attractive teenager who appeared to be part Asian. Though it was winter, she wore a short skirt and sat with her knees together, hands in her lap, and gazed at me.

“I really loved your story,” she said.

“Thank you.”

“I’m Aspen.”

“That’s a pretty name,” I said. “Are you named after the famous resort?”

“You mean where all the phony people go?”

An older man I took to be a professor was also talking to me, and I tried to be polite: No, I was not in the program; I’d quit. Yes, academic life was rather stultifying, hijacked by misanthropes. I’d grown tired of playing the scoundrel in their romance.

Aspen laughed at my remarks. I tried not to look up her skirt. She had the body of a woman but the face of a child, and her eyes shone. A young man with a red nose and a muffler slung around his neck wanted to talk to me about my story. “It’s the fish-out-of-water formula, isn’t it?” he asked.

“Right, of course — or it’s just telling things the way they are. I think they end up being the same.”

“Do you live in town?” asked the red-nosed man.

“Right over by the Fareway,” I said. “In the Colonial Apartments.”

“I’d like to see some more of your work sometime,” the professor said.

“I’m here every Saturday.”

“I understand there’s a tape of one of your stories circulating.”

“If there is, I don’t know about it.” I returned my attention to Aspen. “Isn’t that where Hunter S. Thompson lives, Aspen?”

She smiled. “Do you want a ride home?” she asked. “I live over by the Fareway, too.”

The professor wore a scandalized expression. The red-nosed man in the muffler looked pleased. I said good night to them both.

Aspen led the way out to the parking lot. Her legs were strong and well shaped: thick at the thighs, round at the calves. I would learn that she was an athlete, among other things. “I can’t believe you live in the same neighborhood as me,” she said.

“I’m just a few feet from the Fareway,” I said. “Do you ever get the rotisserie chickens there?”

“I’m a vegetarian.”

We had trouble finding her father’s car. It was cold out. She laughed as if it were fun to be lost. “What if you raped me right here in the parking lot?” she said.

“The townspeople would probably burn me at the stake. What color is the car?”

“White. Ah, here it is.”

Aspen talked giddily and drove as if the big steering wheel were a prop on the set of an old black-and-white movie. She said she was in high school and was going to be an actress or an artist or a singer in a band. She talked more about what if I raped her, her face tilting up at me, her eyes brimming with light. Pulling up in front of my apartment, she said, “Oh, this is where you live.”

“Yes, down in the basement. Number 9.”

“Can I come down sometime?”

“Anytime,” I said.

“I want you to teach me how to blow smoke rings,” she said.

A few days later there was a blue-tinted handmade card from Aspen in my mailbox: a superimposed nude on the front, the note inside littered with stars. Several nights after that I was frying a piece of fish for dinner at about nine o’clock when there was a knock on my door. I answered, the sizzling pan in my right hand. It was Aspen. I have a fan, I thought.

“Come in,” I said. “I was just cooking dinner. Would you like some fish?”

“No, I’ve eaten,” she said. Her eyes roamed the small, cluttered room.

“Oh, that’s right,” I said. “You don’t eat fish.”

“I eat fish sometimes.”

She sat on the floor at my feet, ignoring the perfectly good swivel chair nearby. She told me she had thought about my story for a week. I ate the fish with boiled potatoes and butter, wondering if I should ravish her on the floor. Though I’d reached the age at which I’d become tediously law-abiding, I was still willing to make the occasional exception. She stayed for two hours and recited her entire sexual history, which was impressively long for a seventeen-year-old. She wore a low-cut blouse and shot me tantalizing flashes of white cleavage and a smile that she knew could start an old B-movie zombie on fire. She told me she was an honor student with a 4.0 grade-point average; that an exhibit of her photography was showing in New York City; that she was going to win a full art scholarship to college — if she could get a reasonable grade in algebra.

“I don’t even know what algebra is,” she said.

“Someone made it up a long time ago,” I told her. “Like astrology. But don’t worry. Any arithmetic that has to steal from the alphabet can’t be legitimate.”

“Fuck you!” she shouted, startling me. Her eyes crinkled with something like affection. “Have you read Lorrie Moore?”

“Oh, yes. She’s good, isn’t she?”

“I think she’s the best in the world. I’m going to write her a letter soon —” She leapt up to seize from my shelf a copy of Robert James Waller’s bestselling novel The Bridges of Madison County, which my father had sent me in hopes that some of its magic would rub off. “What a piece of shit this one is,” she said. “I read the whole thing and laughed. Can I have it?”

“What for?”

“I’m going to circle all the bad sentences, then I’m going to burn it. Have you read it yet?”

“No,” I said.

“It’s a scream,” she said. “You won’t be mad at me for burning it, will you?”

I wondered why this smart, attractive girl would want to spend an evening with a thirty-seven-year-old janitor who had not had a girlfriend in many years. I thought of offering her a drink. I wondered again if I might ravish her, but it seemed the opportunity had passed, and I didn’t want to botch everything with my only admirer. The prospect of having a fan who would come visit me was much more exciting (I told myself) than having casual sex with a high-school girl.

“Fuck you!” she shouted at me joyfully several more times (Yes, well, of course, wouldn’t I like that?) before she finally rose to leave, my copy of Bridges tucked securely under her arm. I walked her to the door, lightheaded from my once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, which was disappearing forever now that she had seen me in my rumpled, cheap-wine-and-fried-fish element. She slunk down the green basement corridor, looking back twice, chin on shoulder, lashes lowered, with a smile that made me dream about her all night.

Against all expectations, she showed up again four nights later with cigarettes, a bag of candy, and a firm idea already of who or what I was, which I wished she would’ve shared with me. “Let’s go outside,” she said. “Have you seen the moon?” We sat on the park bench that faced the Fareway, and I felt like a mental patient with a candy striper as she tore open the wrappers. “Candy for the madman,” she said, portioning out sweets to me.

“Madman?”

“You write about fucking dead girls.”

“It was only a story.”

Her eyes went wide. “I nearly got my bellybutton ripped out the other night, did I tell you?”

“What happened?”

She lifted her shirt to show me a bandage on her stomach. “I had it pierced last week,” she said, “and I was with Eric down along the railroad tracks, and there’s a place where the train goes over, and we jumped into this hole, but I caught my ring on something, and it ripped out.”

“Lord,” I said, angling to get a glimpse of her breasts.

“God, I’m never going to get pierced again. I don’t have any tattoos either.”

“You’re different from the rest.”

“Did I tell you I’m going to be famous by the time I’m twenty-two?”

“I have no doubt that you will be.”

She lit a cigarette and shoved the pack toward me: Camel Lights, which smelled like a Tanzanian dung fire. Research has indicated that light cigarettes are no better for you than cigarettes with actual flavor, which just goes to show you the power of advertising. America is going light, the way the Romans went soft. I lit one of the cigarettes, feeling as if I were wearing state-issue pajamas and my hair had been combed by the aide that morning. I had a stupid erection sitting there on the park bench under the cold moon.

Aspen came over to my basement apartment two or three times a week, always at night, sometimes knocking on the window in her miniskirt. My heart would soar, and I’d lift the curtain and wave her down. The landlord had recently given me a couch, and Aspen would fall into it and light up a smoke as if she were at the house of one of her high-school buddies whose parents had gone to Lake Tahoe for the weekend. I smoked her dung-tasting cigarettes and basked in her spell. She was not ashamed of anything and continued to confound me with her frank and cheerful accounts of her sexual adventures. I forced myself to be open and honest, imagining this was my true appeal, the only thing she could possibly admire about me or my work. She spoke often of suicide. One of her favorite photographers, Diane Arbus, had supposedly documented her own suicide, which Aspen thought was wonderful. I’d pondered suicide a great deal myself, but I didn’t think it was wonderful.

Every night I listened eagerly for Aspen’s footsteps on the stairs or her rap on the window, convinced that each time I heard it would be the last. Yet every few days she reappeared, lovely and inscrutable, with her big dreams and long dark hair, her ears that stuck out, her laughter that bubbled up like a child’s. She worked on her smoke rings and told me about her boyfriends and her classmates and the books she’d read and the bands she liked and the artists she loved and the beauty of suicide and all the people she knew who were dying of AIDS, which, the way she described it, was a slow-motion, fire-lit, tragic love disease.

She introduced me to many of her friends, all of them female, none of them impressed by me. Once, I made it to the high school to see her in a one-act play she’d written, and I found myself sitting with parents who were not much older than I was.

“I hate all men,” Aspen often announced, as others might say, “Damn,” or, “Gesundheit,” which was strange to me since it was her sober and responsible Korean father — a history professor at the university — who had raised her. Aspen’s parents had divorced when she was two, and her flighty and mystical Irish-Choctaw mother had gone on to have other children, Aspen’s half brothers and sisters, some of whom Aspen barely knew.

One day Aspen sat in my swivel chair as it rained, the trees outside the basement window flailing in the wind. Her mother was back in Iowa, and Aspen had just been to see her. “On the way,” she told me, “I saw seventeen squirrels dead in the road.”

“How terrible.”

“My mother said they must have all been Sagittariuses.”

I laughed until I saw Aspen looking curiously at me. It hadn’t occurred to me that she might be serious. “Maybe there was a war with the beavers,” I suggested.

“Fuck you!” she shouted.

“I’m going to have a glass of wine,” I said, drying my eyes. “Do you want one?”

“What kind of wine is it?”

“Bird wine. . . . Cheep-cheep.”

“OK.”

I poured her a jar in the kitchen. Great, I thought. Not only am I contemplating statutory rape, I am contributing to the delinquency of a minor.

One drink did the trick. Her cheeks flushed, and she turned giggly on me. It was her Asian genes, she insisted. At the last swig from her jar she started to tip over in my rusted swivel chair, and I had to lunge to save her. This was the first time I had ever touched her, and she laughed and tilted her head back, her eyes flashing, her pretty teeth shining at me.

Somehow I managed to right her and get safely back to my own chair. I should run away to Saudi Arabia, I thought, and become the guardian of a harem. I had to put a pillow in my lap.

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

“Nothing,” I said. “No more wine for you.”

“My father is out of town,” Aspen told me one night. “I’m afraid to sleep in that big, empty house alone.”

You have to go for it, I thought. God or Nature or someone like that has given you a gift. The ripened peach has fallen to the grass. Soon you will be old and even more ridiculous and won’t want to remember the days when the radiant and promiscuous girl kept knocking on your door, and you kept turning her away.

“You can stay here if you want,” I said, “but I have to go to work tonight.”

“What time?”

“Before 2 A.M. The toilets must be gleaming by seven.”

“I can’t go home,” she said. “I don’t want to be alone.”

“Stay here, then,” I said. “I’ll be back before the sun comes up. Or come with me to city hall. You can shoot baskets or listen to the radio. I’ll show you the haunted office.”

“No, thank you.”

“You don’t believe in ghosts?”

“Oh, yes, I do.”

We each drank a jar of red wine, and at 1 A.M. I told her I had to go to work. “Walk me home,” she said. She lived only a few blocks away. Someone had abandoned a container of liver from the Fareway, and I kicked it and made up an R & B song: “Kick the Dish of Liver.” She danced through the empty supermarket parking lot in the moonlight.

Halfway up the walk in front of her house I stopped and said good night. She urged me up the stairs to the porch. The front door was open, and I could see into the home where she had grown up.

“I really have to go,” I told her.

“Wait just a minute,” she said. She went inside and brought out two scrapbooks full of childhood photos. She looked the same in the pictures as she did now: round faced, big eared, and brimming with life. On the porch was a dismantled art project she’d recently exhibited at a local gallery: a vacuum-cleaner sculpture and a medicine cabinet with tiny photographs arranged inside. I was flattered by her desire to share with me the things that were important to her, to stand with me on her porch in the spring night air when she was alone and afraid.

“I really do have to go mop out the gymnasium and suck up all the clumps of pubic hair from the corners,” I told her. “If you get scared, come over and find me. I’ll be in the only lighted window.” Then I trotted down the stairs and walked to work through the watery strips of moonlight under the trees that shivered in the April wind.

Aspen spent her eighteenth-birthday eve with me. We watched the clock roll to midnight and each drank a jar of wine. Hooray for Aspen! She confessed that she had been thinking about suicide lately. (Remember the burden of youth? And how everything corrupt and ancient seemed so new?) I told her she was a delight to me, and I would be angry if she deliberately went away. She stayed till one, and we listened to the new Mazzy Star album. In a month she would be off to art school. It was time for me to leave too. I was restless and tired of cleaning floors and looking at my aging dog face in the mirror. The readings at the college had been discontinued because, someone had told me, there had been too much interest being paid to work “from outside the program.”

Since we were both leaving, I thought it was time I finally slept with Aspen. Something had to happen between us besides a good-luck handshake. I would never have this opportunity again. She was of legal age now, a woman. She promised we’d have a bon-voyage drink together. “A double farewell,” she said.

I bought a bottle of Bordeaux for the occasion. It was a cheap bottle of Bordeaux, but expensive for a part-time janitor. I didn’t know how I would seduce her — I had grown too accustomed to being her friend — but I felt it must be done somehow. It was what she had wanted all along. The thought of going to buy condoms was strange to me. I was from the pre-AIDS era, when the pill had made condoms seem out-of-date. Plus my understanding was that they were ineffective 10 percent of the time anyway — a Russian roulette of romance — and you couldn’t feel anything, like cracking a safe with balloons on your fingertips.

But Aspen never came over to see me off. The night before I left, I drank the bottle of Bordeaux alone. It was not a very good Bordeaux. At least I hadn’t been pathetic enough to buy any condoms.

And then I was in a new place in the northwest corner of the only national forest in Nebraska. I had a part-time cooking job at a hotel and a rough little cottage on the edge of town, and for the first time in my life I was having trouble maintaining my sanity. I was working hard on the writing, but nothing was coming of it, and I realized there would be no girl in this town, just me sitting in this damn room alone, getting old. To quell my suicidal impulses, I promised myself that this would all pass, and one day I would be dust, grateful to be forgotten. In the end, time is as good as death, and suicide is a bad example to the people you love. I wrote Aspen a self-pitying letter. I didn’t expect her to answer, but she did, with sympathy and tenderness.

Summer came along, curled and fried at the edges, the air like clouds on the planet Mercury, with tides of rain-fearing grasshoppers rushing through the weeds and the leaves on the wild rhubarb turning brown as if from flames. I stayed up late, unable to sleep in my hot, thin-walled shack. Aspen sent me breathless, hasty, stream-of-consciousness letters written diagonally across the page or on gold-flaked paper. She was sorry she hadn’t seen me off, she said. She was taking twenty-two units per semester and at this pace would graduate in three years. She didn’t like the university and was thinking of transferring. She promised she would visit me before the summer was over, but it never happened. She was too far away and too busy. She would be dizzyingly famous soon. She had many friends, a new boyfriend every few weeks. Certain that our correspondence would fade and I would never see her again, I wrote her without restraint. I told her that I loved her and missed her. When she did not write back, I knew that she had given me up for a sap and a fool, but then a letter would arrive, always hasty but fond and full of life.

One year later I was at my parents’ home in southern California, recovering from a mental breakdown and a chronic cough and trying to get three novels into shape, hoping one of them, if Zeus struck me with a lightning bolt, might accidentally sell. One afternoon at five o’clock Aspen called. She had been traveling across the country on summer break with her friend Drew.

“Can you pick me up?” she asked.

“Where are you?”

“Huntington Beach,” she said. “Where is that in relation to you?”

“About eighty miles north. What are you doing there?”

“I’m staying with my sister Ariel. I would drive down, but I’ve split up with Drew, and I don’t have a car.”

“You want me to come get you now?” I said. “It’s rush hour.”

“If it’s too much trouble, I can fly down.”

“No, no, give me the address.”

“As soon as possible,” she whispered into the phone. “I can’t stand it here anymore.”

The address was easy to find. Aspen’s once-gorgeous half sister lived on California Avenue, a short walk from the ocean. Ariel was the famous one in the family, an ex–Penthouse Pet. Now she worked at a bikini bar, where the men mauled her and tipped lavishly all night. I found a place to park across the street. The door to the apartment was open, and Ariel, sitting wearily at a glass dining-room table, gestured me in as if I’d come to fix something. She’d made several appearances in Penthouse and was now thirty-three, an eight-month member of Alcoholics Anonymous, drug problem on hold, a handful of abortions under her belt, the somber letters GOD tattooed on the back of her hand.

“I’m a little early,” I explained. “I thought the traffic would be worse than it was.”

“Sit down if you want,” she said. “I don’t know where Aspen is.”

Aspen had told me that she wanted Ariel and me to get together. She thought we were some kind of match, both desperate and aging fast. I was forty now, and the idea of marriage to a troubled, dissolving pinup girl was laughable. I imagined myself cooking and cleaning house while Ariel perished from boredom in front of The Jerry Springer Show. I sat down in the only other chair in the room. The television was going without any sound. Three scrawny kittens roamed in and out the open door like little drunks.

Finally Aspen arrived, the late-afternoon sun silhouetting her in the doorway. She was as I remembered her, except more grown-up. She had gone to buy a pizza for her sister, who was so tired of living she rarely took the trouble to eat. I grabbed Aspen’s bags, eager to leave LA and everything associated with it. Aspen spent fifteen minutes saying goodbye. There were tears and promises exchanged between the half sisters, who’d been deliberately kept apart by their father for many years. Fog began to blow in, and I felt as if we were jaded bohemians playing out an exhausted California script, the classic genre tale of decline: Ariel was the bad influence; bright and talented Aspen still had the world before her.

Aspen had never been to San Diego before. On the way there I described it for her: a place, as novelist Nathanael West put it, where people went to die; a place so vapid many people’s heads collapsed like pumpkins in a vacuum as they combed the beach with their metal detectors or started their lives over again, thinking that a year-round mean temperature of sixty-seven degrees was going to make some kind of difference.

“You’re the first sane person I’ve talked to on this whole trip,” Aspen declared as we entered the flow of Interstate 5.

“That’s a good one,” I said.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I fell apart. I’m not working. I’m forty years old and live with my parents.”

Aspen thought this was funny. She thought everything I said was a joke — except for the time when I’d written that I wanted to butter her legs. She’d taken offense at that: what if her father had read it? I’d apologized for wanting to butter her legs. If she wanted to go around with dry legs, that was her business.

She chattered about her miserable trip: Drew — her traveling companion, an English/theology double major — hadn’t spoken more than twenty words across twenty states. He’d just chewed his nails and chain-smoked Native American cigarettes, then made a pass at her in San Francisco. “Did I tell you about my new boyfriend, Matt?” she asked.

“I’m not sure. It’s hard to keep track of them all.”

“He’s six foot six. Oh, I miss him.”

I dodged through traffic. The Radiohead song “Creep” played on KROQ. “This is my theme song,” I told her.

She sang me the unedited version with a giggle. Her face had changed: The roundness was gone. Her cheekbones had emerged. Her eyes were sharp and lush; her plum-colored lips lifted slightly, as if to attract hummingbirds. Her voice came from the middle of her chest, then hovered in her throat like music from a fine wooden box. She told me all her friends were in love. These were the same friends who, like her, shouted, “Fuck you!” whenever someone said something clever.

“All your friends but me,” I said.

“And Ariel,” she answered moodily, perhaps disappointed that her sister and I hadn’t hit it off. “You know, she used to be the prettiest girl I ever knew. Now all she wants to do is put a bullet in her mouth.”

“What goes up must come down.”

“Do you have any cigarettes?” she said.

“No, I quit.”

“Traitor. Stop and get some.”

My parents had conveniently gone to Lake Arrowhead for two weeks. I took Aspen’s bags upstairs. When I came back down, she was studying one of my great-grandmother’s oil paintings. “I have good wine tonight,” I told her. “One of the advantages of living in the sanitarium.”

We sat out back with our glasses of good wine and smoked cigarettes under the stars. Aspen’s favorite topics were still sex, death, and art, but mostly sex. She told me her new stories. She was blithe, even clinical, in her descriptions: “My boyfriend and I get drunk and fuck for hours, but we never come, because we’re too drunk.” I didn’t have any new stories, so I retold a few old ones. She wanted to hear about the girlfriend of mine who’d gotten the abortion. “Scrape, scrape, scrape,” she croaked, crooking her finger at me.

I shook my head.

“Would you be mad at me if I got an abortion?” she asked.

“I wouldn’t bake you a cake.”

“Does abortion make you angry?”

“I like people. Babies are people.”

“If I had a baby, you could have it,” she said.

“I’d love to have your baby.”

She laughed at the incongruity, lighting up a cigarette and crossing her legs. “You know, I hate all men.”

“Yes, I’ve heard that.”

“Lesbians are good people,” she continued.

“How are they, in essential character, different than other people?”

She shrugged cheerfully. “A third of the girls at my school are out,” she said.

“Out of what?” I said, feigning ignorance. “Blue-cheese dressing?”

“No, out of the closet, silly.”

“My, my.”

“I hate all men,” she repeated.

“I’m a man,” I said feebly.

“You are not a man,” she replied affectionately.

“What am I, then?”

“You’re Poe!” she cried.

What is Poe? I wondered. Some androgynous, benevolent, parental bumbler? What was I to her, and why had she come all this way to see me? Was it because I’d told her I loved her? Was it my talent as a chronicler of my own chaos and failure? Was I her confessor, her confidant, her buddy?

Aspen looked up at the brightest star and said, “Make a wish.”

I wished that I would make love to her.

At midnight, after several glasses of wine and enough cigarettes to give a hippopotamus emphysema, I showed her to her room.

The next morning we went to Tijuana, Mexico, a dangerous and exciting place in Aspen’s mind. We drank with the tourists, and she bought junk. Because she got drunk so easily, we’d have just one drink, then take a walk. We had a beer and then a walk; a mango margarita and then a walk. She bought a pair of leather sandals, a blanket, and a purse for her mother; and a big bottle of Kahlúa for Matt. We stopped at a cantina, and she had two beers this time. Leaving the bar, I had to grab her arm to keep her from getting flattened by a taxicab. I joked about calling her father with the terrible news: Hello, Mr. B.? Yes, flattened by a Mexican taxi. Prime of her youth. She beamed and bubbled with laughter. I was enthralled by this rich, bright, spoiled Irish-Korean child of science and atheism among the poor Mexican Catholics. The Mexican men gave me the thumbs-up as we passed. Aspen took photos of the dirty beggars, the orphans selling Chiclets, the strolling guitarists, the relaxed whores out in front of the Del Mar Hotel. I smoked cigarettes in the sun while she pored over cheap electroplated jewelry.

Late in the afternoon, we sat in a bar off the beaten track, drinking Pacificos and smoking harsh Mexican Marlboros. Aspen enjoyed the way I talked about “the soul,” and she pretended to point to hers. It was like a discussion about Santa Claus to her. I said that her soul was the only thing on earth she could not lose. She wondered if it would be corrupted if she slept with nine more men. I told her nine was the limit. She wanted a daiquiri, but the bartender didn’t know what one was, and I didn’t know how to say rum in Spanish. We had a third Pacifico, and if I could have, I would’ve stopped time right there.

It was evening when we got home. In the dim living room Aspen lay on the couch, her blouse loose at her waist, exposing her belly. I was drunk — on her, not the alcohol. I had not let myself be this entranced by a female in as long as I could remember. I knew that whatever happened, I would never forget the strange flavor and chemical force of this night: the delirious exhaustion, the hue of the sky at dusk, the smell of my mother’s carefully tended sanitarium flowers flooding through the screens. Aspen drew extraordinary subjects out of the air, explaining to me, for instance, the difference between fission and fusion. I kept thinking: She is no longer a little girl, and she has come all this way to see me.

I was so anxious and afraid of failure, though, I didn’t know if I would be able to go through with it. It had been too long. I had run the ship aground too many times, worn the fool’s cap, been clobbered over the head by lust and woken up to the roaring of elf laughter. The transition from fan to friend to confidante to lover seemed too great a leap. My hopes were alternately lifted and dashed like waves on a beach. She was too young for me, of course, and she had a boyfriend. Time was rushing away, the room growing dark. We had shared many miles and secrets together. She was different from any other woman I had ever known: her boldness, coarseness, music, sympathy, laughter. I knew that I would not go through with it, violate the trust. I also knew that I must.

Upstairs she lay in bed below a portrait of me as a youth, painted by a drunken artist. I was about to turn in, to my separate bedroom. I considered my coffin: its solid sides, its earthy comfort. She was lying dreamily below my portrait, gazing up at it. The pose seemed an invitation, a fitting conclusion to the evening.

I lay down beside Aspen and kissed the corner of her mouth. She turned her face away. I kissed her ear, then the part of her belly that was exposed.

“No,” she said.

I touched the curve of her waist, kissed her head. Her face was rigidly averted and concealed by her hair. A clam would have expressed more romantic interest. I had been mistaken all along. I mumbled an apology. She asked me to lie with her for a while, reaching up to drag me down, but I wanted only to assuage my embarrassment. I pulled away, feeling oafish and baffled, but it was an old familiar feeling, and I made the old familiar adjustments.

The next evening, after a day at the racetrack and a long walk on the beach, I drove Aspen to the airport. She was traveling standby and was on a waiting list. If she missed her flight, she’d miss her mom, whom she rarely got to see. I followed her to the gate (this was when they still let you do that), and her coverall buttons set off the metal detectors. She was irritated. When I told her there was a good chance she might not make the flight, she snapped at me. I shut up, found a seat, and crossed foot onto knee; we waited for the boarding announcement.

A plane landed, and the passengers filed off. The families kissed and hugged.

“I hate public displays of affection,” Aspen said.

“I’m glad you told me that.”

When her name was called for boarding, we both hopped up. “You made it,” I said, and I put my left arm awkwardly around her and gave her a squeeze. “No public displays of affection,” I said.

As Aspen turned to go, the woman sitting next to us, who had been watching us for a while, regarded me strangely. Her expression seemed to say: Why don’t you kiss her? You may never see her again. Why don’t you tell her how much she means to you?

Yes, of course, you’re right, I thought, but I was already moving through the airport as fast as I could go.