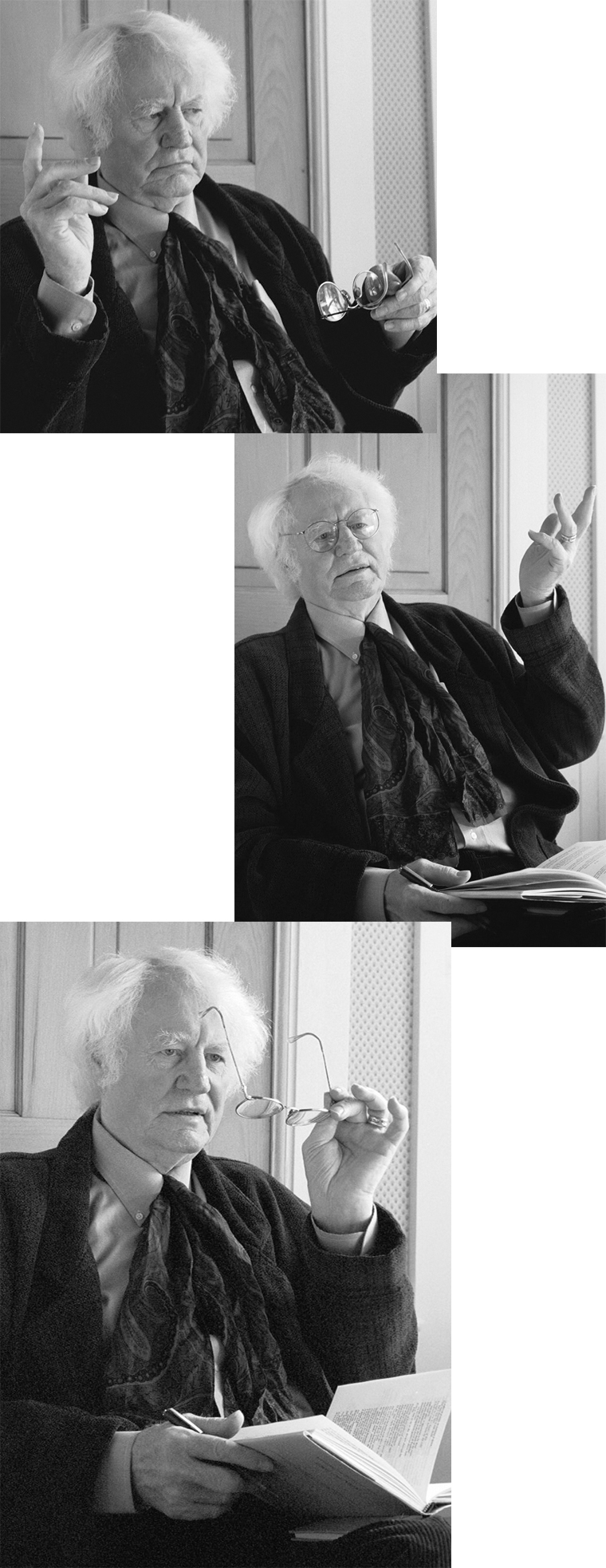

Robert Bly, poet and cultural firebrand, has been stirring up controversy for the past forty years. Today, at the age of seventy-seven, he is writing what many recognize to be the most important poetry of his literary career.

Bly is best known for his 1990 book Iron John (Vintage), which proposes that modern men suffer from a lack of male mentors and initiation rituals. The book served as a pivotal document and lightning rod for the burgeoning men’s movement, and Bly became one of the movement’s central figures, leading workshops — along with psychologist James Hillman and storyteller Michael Meade — in which men learned to express their hidden anger and grief. Critics accused the movement of being antagonistic toward women, but Bly dismissed the charge as “oppositional thinking”: the assumption that anything for men must also be against women. Bly has since joined with Marion Woodman, a Jungian analyst of feminine psychology, to lead workshops for both sexes.

Born in western Minnesota, Bly joined the navy out of high school and later graduated from Harvard. An interest in his ancestry inspired him to translate some Norwegian poets into English. It was the beginning of a second career as a translator. He started a magazine called The Fifties (and later The Sixties, and then The Seventies), in which he published Pablo Neruda and César Vallejo in translation prior to their becoming well-known in the U.S.

One of the first literary figures to publicly oppose the war in Vietnam, Bly cofounded American Writers against the Vietnam War in 1966. When he won the National Book Award for his poetry collection The Light around the Body (out of print), he donated the prize money to the antiwar effort.

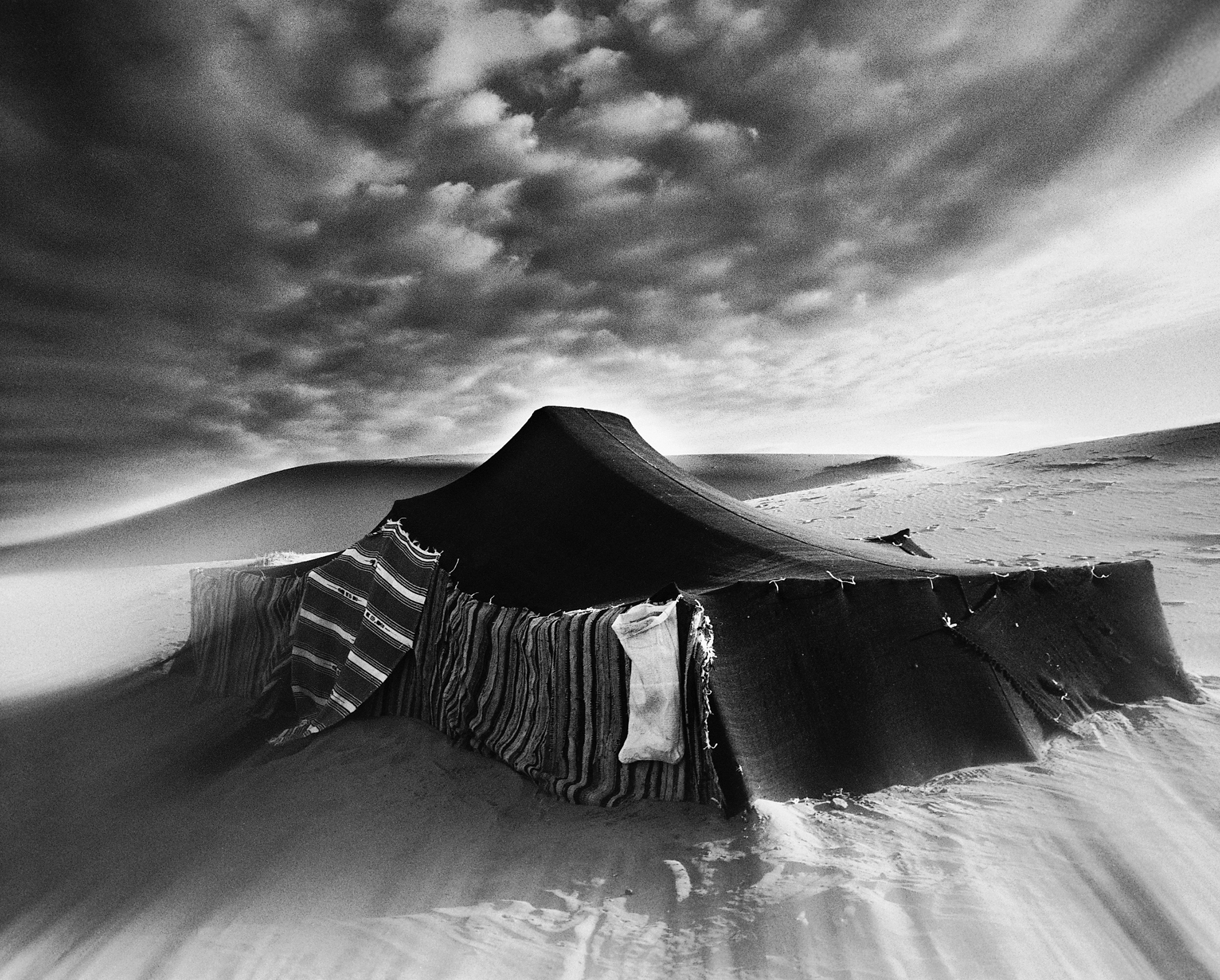

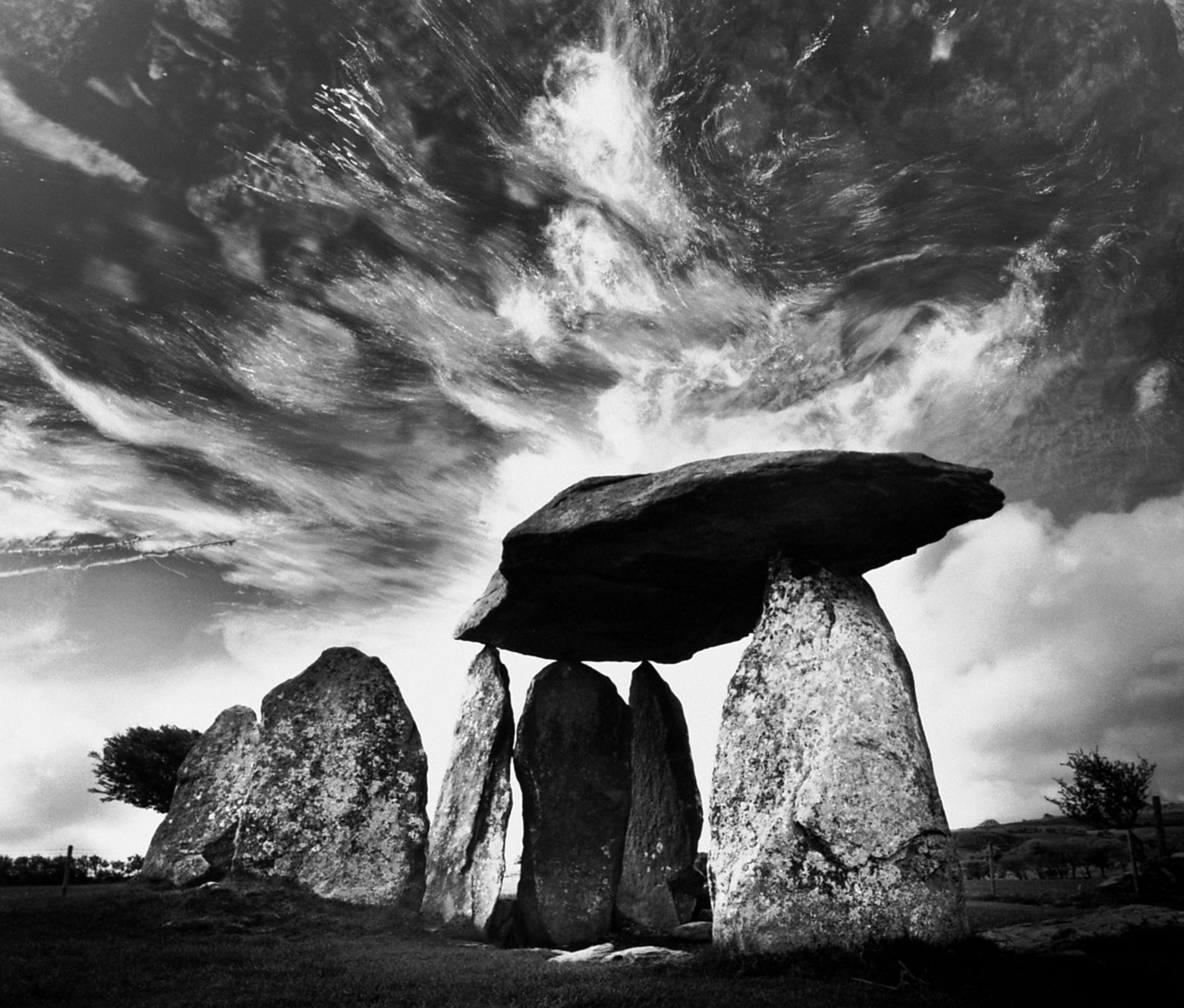

Bly is so identified with men’s work that few are aware of his early association with Goddess spirituality. Long before interest in the Goddess became more widespread, Bly wrote extensively about the feminine side of the divine, and in 1974 he started the Great Mother Conference. (The thirtieth annual gathering of the conference — now called the Conference on the Great Mother and the New Father — will be held June 5–13 at Camp Kieve in Nobleboro, Maine. To learn more, visit www.greatmother-conference.com, or send an e-mail to greatmother@yellowmoon.com.)

In his most recent book of poems, The Night Abraham Called to the Stars (Perennial), Bly borrows from Islamic literature a poetic form called the ghazal. (He pronounces it “guzzle.”) The poems celebrate joy in unexpected ways — joy at death as well as life, joy at loss as well as gain, joy at despair as well as wonder. Bly’s other recent books include The Maiden King: The Reunion of Masculine and Feminine (Henry Holt), with Marion Woodman; Eating the Honey of Words: New and Selected Poems (Perennial); and his collaboration with Sunil Dutta on translations of the Islamic poet Ghalib, The Lightning Should Have Fallen on Ghalib (Ecco Press).

The following is not so much an interview as it is a conversation between two authors and thinkers. Michael Ventura has been writing his biweekly column “Letters at 3 A.M.” for twenty years. It appears now in the Austin Chronicle and online at www.austinchronicle.com. He’s published three novels, written several movies, and is the author of four books of nonfiction, including We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the World’s Getting Worse (HarperCollins), with James Hillman.

“While waiting for Robert Bly to arrive at my apartment,” Ventura writes, “I wondered: What can that magazine be thinking, asking two nonlinear thinkers to combine their nonlinearity into a printable conversation? We’re in trouble. But, as Robert repeats in one of his new poems, ‘It’s already too late!’ ”

— Ed.

ROBERT BLY

© Mark Stanley

Ventura: For thirty years you’ve conducted a gathering called the “Conference of the Great Mother and the New Father” — though in conversation it’s invariably called the “Mother Conference.” At this gathering, through story, song, the arts, and play, you investigate goddess and god energy. Generally speaking, what do you mean by “goddess energy”?

Bly: By “goddess energy” I don’t mean pagan energy, but the powerful and clear feminine energy that one often feels in nature — for example, in the moon, or in a blossoming field. I don’t really know if it’s masculine or feminine, but it feels feminine because of its generosity.

Ventura: What goddess energy, or god energy, is most at work in the world right now?

Bly: Something called the “negative father” or the “poisonous father” — the one who curses the children.

For example, let me read you something from the Journal of Psychohistory, and by “psychohistory” they mean damage caused by brutality to children, from the beginning of history until now. Listen to this:

In the first Gulf War all eleven of Iraq’s major power stations were destroyed, along with 119 substations. . . . Iraq’s eight multipurpose dams were hit repeatedly and seriously damaged. Four hundred seven water-pumping stations were destroyed; eleven municipal water and sewage facilities were hit by bombs. . . . Bombs hit twenty-eight community hospitals and fifty-two community health centers. Six hundred seventy-six schools were damaged and thirty-eight totally destroyed.

And so on, and so on. All that happened in the first war. The journal article goes on to say that “the Pentagon did in fact admit it massively targeted civilian structures to ‘demoralize the population.’ ”

So one of the energies at work right now is the insane, obsessed father who tries to damage the children. In other words, we took Iraq and bombed it back into childhood.

Ventura: In that the U.S. rendered the civilians of Iraq helpless?

Bly: Exactly. That’s what happens when you get rid of the electricity and sewage systems and hospitals: you reduce an adult country to a child country. That’s the negative father who kills his children. And because Bush Senior wasn’t doing it to kids on our block, he got away with it.

And now we get his son, who doesn’t think that the child was punished enough. Saddam Hussein doesn’t have nuclear weapons. But Bush says, “Never mind! You did have them. I know you did. Now get over here. I’m going to give you a whipping.” That’s what I think is going on in Iraq. That’s why it’s so desperate and insane. The negative father is coming forward almost nakedly and beating a country that’s already on its knees. Why do you think it’s so sad right now in the United States? The men and women lack spirit, and they’re all depressed.

Ventura: You and I have spirit, and we’re not depressed. And more people are voting in the primaries than have recently.

Bly: I know, but the people as a whole — you don’t see them out there fighting all this, as they did in the 1960s.

Ventura: True, electing somebody to fight for you is not the same — though it’s better than nothing.

Bly: So what is the source of that depression? Well, when you find out that your father has been beating all your sisters and brothers, it’s depressing.

Ventura: Because we’re all brothers and sisters, including the innocent Iraqis.

Lately I’ve been thinking of another factor that drains our spirit. Ever since the advent of radio, when advertising began to be broadcast, the air has literally been filled with lies. You turn on the radio or the television, and every ten minutes you get a barrage of lies. The advertisers make claims that they know are false, and that the listeners know are false, but there’s some kind of unspoken agreement: “We’re telling lies about this product to get you to notice it.” It’s terribly depressing to be surrounded everywhere by lies for nearly a century. We can’t take it anymore, but we aren’t conscious of it, and it comes out as depression.

Bly: I don’t think we believe that a Great Mother is lying to us. It’s a father who’s lying to us. The whole system, in a way, is a father system.

Ventura: It’s a patriarchy, so it’s a father who’s lying.

Bly: Exactly. And we eventually get the sense that our own father is lying to us.

Ventura: These lies are literally in the air; they’re being broadcast, signals bounced everywhere. For your lifetime, seventy-seven years, we’ve lived increasingly in an atmosphere of lies. As a result, language has become thinner, less trustworthy. When I hear kids saying “like, like, like” throughout a sentence, even the really smart ones, it’s not that they don’t know what they’re thinking; it’s that they don’t have much faith in saying it. That’s what happens when the lie literally becomes the medium of exchange in commerce.

Words are very important to us. “In the beginning was the Word.” The myths say we received language from the gods. Now the angels, the messenger gods — angel means “messenger” — have been corrupted or driven away.

Bly: Whenever you have a culture completely run by gross capitalism, all of the gods are driven away. Well, then what? What does that mean when those gods are not present?

Ventura: We can go round and round about what it means, but the more urgent question is what do we do — specifically, in terms of language? How do we save the language from the effect of all those lies?

Bly: We have to remember the possibility that some kinds of language bring joy. My son-in-law Sunil Dutta helped me translate the great Urdu poet Ghalib, for a book titled The Lightning Should Have Fallen on Ghalib. Sunil helped me find a new version of a Kabir poem. Four lines. It says:

The buds are shouting The gardener’s coming Today he cuts the blossoms Tomorrow, us!

I say, if you can’t say that in an enthusiastic voice, just forget it. Most fear has inside it the hidden fear of our dying, but we have the choice to say, “We’re going to die anyway! What’s the big deal?”

Ventura: I hear in that a reckless joy that can pierce depression.

Bly: The language has got to be vital to give that joy. It has to be a live language, with live metaphors, to be a source of joy.

Ventura: In your book The Night Abraham Called to the Stars, you write: “All our language is woven from animal hair.” Is that true even of the language advertisers use to lie?

Bly: Maybe with radio and television, the animal connection is gone. Our language comes from our long association with animals and their grunts, not from television, and not from our long association with university professors.

Our spiritual life is a constant battle between the part of the soul that loves others and the part of the soul that will gladly eat them up in a moment.

Ventura: Maybe that’s why the kids speak so hesitantly. The animal connection is gone in print, too. Good language is a pleasure of the flesh, but when you have this homogenized style in all the magazines, that’s not a pleasure of the flesh anymore. It’s like reading milk cartons, or cereal boxes.

Bly: It’s worse. It drains energy out of you.

Ventura: One way to stop your energy from being drained is to face what you fear head-on. In some of the unpublished poems you showed me, you revel in precisely what many of us fear. You write: “It’s all right if I feel this same pain till I die,” and also, “It’s all right if the boat I love never reaches shore.” Those aren’t very American ideas, Robert. [Laughter.] What do you mean it’s all right to feel the same pain until you die?

Bly: The question is, who is this whiny one inside us who wants to be happy all the time? In the Muslim tradition, that whiny one is called the nafs, which is the greedy soul. You can also call it the insatiable soul, the rapacious soul. That’s who’s running the war in Iraq right now. The Sufis say the nafs is part of our ancient animal-soul, which is determined to have food, power, and sexuality, and to stay alive, even to the detriment of those closest to us. So our spiritual life is a constant battle between the part of the soul that loves others and the part of the soul that will gladly eat them up in a moment.

In The Night Abraham Called to the Stars, I wrote a little stanza:

I live very close to my greedy soul. When I see a book written two thousand years Ago, I check to see if my name is mentioned.

That will give you a little taste of the greedy soul. It’s my greedy soul I’m talking to when I say, “It’s all right if I feel this same pain until I die. It’s all right if the boat I love never reaches shore.”

Ventura: But we live in a culture that makes boats for reaching the shore, and for no other reason. We turn on the TV, and there are dozens of commercials saying, “Take this drug. It’ll get you to shore.” or, “Buy this car. It will get you to shore. We guarantee it.”

Bly: TV always tells us about what other people love: “Everyone loves this car. Why don’t you get one?” But if we love a boat, I don’t think we care if it really reaches shore. You can write a poem you love and not care if it’s published or not.

The storyteller Gioia Timpanelli tells a tale about Saint Francis: He comes back home one night with his friends. They’ve been doing all these good deeds, things you’d think they’d be praised for, and now it’s late, and they haven’t had any food. Saint Francis knocks on the door of a friend’s house, but the friend starts dumping things on him from the second floor and shouting, “Get away from here, you robber, you criminal!” And his companions say, “Oh, this is terrible, Francis.”

“No,” Francis says, “this is perfect joy.”

There’s something wonderful in that. Because the greedy soul wants our friends to welcome us into their houses; when they don’t, the greedy soul is weakened, and another sort of joy comes forward. The greedy part of you wants to get into the house and be comforted and praised, but it gets rebuked, and you’re left with the part that’s never going to get in. Your boat is never going to arrive at the shore, and in some traditions that’s called “perfect joy.”

Saint Francis knocks on the door of a friend’s house, but the friend starts dumping things on him from the second floor and shouting, “Get away from here, you robber, you criminal!” And his companions say, “Oh, this is terrible, Francis.” “No,” Francis says, “this is perfect joy.”

Ventura: What’s joyful about it?

Bly: I’m doing something beautiful and good, but I’m not getting any candy for it. My mother and father are both dead, and they’re not going to give me the reward I deserve for what I’ve done. That’s perfect joy!

Ventura: So the lack of reward, the disappointment, can open a space for something new, a new joy that doesn’t depend upon recognition and reward?

Bly: Exactly.

Ventura: That reminds me of another new poem of yours, “Listening to Sharam Nazeri.” The refrain is, “It’s already too late!”

Bly: Here’s a stanza:

When Nazeri sings, I don’t care if the Second Adam comes down or not; I don’t care if my words Get you to cry or not — it’s already too late.

Someone said to me, “Oh, Robert, that’s terrible. You’re becoming a defeatist. There’s no sense in doing anything if it’s already too late.”

I said, “But you’re never going to get in that house where they’re dumping garbage on you from the second story. It’s already too late, so enjoy it being too late.”

I know sweet vowels and inescapable rhythms. I know how sweet it is when a young woman is here And the old men think of God; but it’s already too late.

There is something joyful when we’re able to realize that everything is already too late.

Here I am; I am all alone. It’s early morning. I am so happy. How can so much grandeur Live beneath my skin? Go on asking; it’s already too late!

Ventura: I love that, because if “it’s already too late,” then you’re free.

In another new poem, you write,

Why do we imagine that we are responsible for all The pain of those near to us? The albatross that lands On the mast began flying a thousand years ago.

One reaction to that could be “You’re abdicating responsibility.” We go to all these therapists to see how we’re responsible for the pain of all those around us, and how they’re responsible for ours. We don’t want the therapist to tell us, “It’s just the albatross that has been flying for a thousand years to get to you.”

Bly: When something goes wrong in a marriage, and it all comes to grief, it’s our habit to think, It’s my fault. But from the point of view of an older culture, each of us has had many past lives, and the suffering that you and your spouse just went through is not coming from your connection to each other. It’s coming from those past lives. The albatross began flying a thousand years ago. The wife or husband who landed at the altar with you began flying a thousand years ago.

Ventura: I look at some couples I’ve known — two people I couldn’t imagine being together on the day they got married, much less ten or twenty years later — and I think, What are they doing with each other? They’re doomed! And then I see these wonderful children, and I know that’s why they got together. The ancestors pushed them together, saying, “We don’t care about your happiness! We want these kids! We want this to go on. We care about this energy going through our line, like some fantastic electric current.” So these ancestors decide, “Let’s hitch these two up.”

Bly: And they tell you, “That’s the way it is, so stop whining!”

Ventura: In another new poem, you write,

Go ahead, throw your good name into the water. All those who have ruined their lives for love Are calling to us from a hundred sunken ships.

Bly: The idea of throwing away your good name is related to an old Sufi teaching. In the twelfth century or so, a discipline grew up in Iran that was intended as a rebuke to the greedy soul. The discipline is this: When a stranger or friend spreads evil rumors about you, you don’t reply. You save the energy you would have expended in defending your good name. Even more important, by allowing bad stories to be told about you, you rebuke the nafs. It gets depressed.

Spiritual teachers began to teach this practice of not defending, which was called the Malamati discipline. Hafiz was a classic Malamati. He sometimes encouraged bad stories about himself in his poems, because he found his spiritual energy increased when he did this.

There’s a lovely story about that: A Sufi came to teach the Malamati discipline in a kingdom, and pretty soon he had ten followers, and fifteen followers, and twenty followers. The king himself was so delighted that his people were following this teaching that he said, “If you’re following the Sufi’s discipline, you don’t have to pay any taxes!” Pretty soon another fifty, and another hundred, and another two hundred came to follow the Sufi. Finally the king’s advisor went to the king and said, “Listen, you’re losing a lot of money here. All these people are not paying taxes. What are you going to do about that?” So the king called in the old Sufi and asked, “How many of your people are really good practitioners of your teaching?”

“We’ll find out,” said the Sufi.

The next Sunday afternoon, before his followers come and cover the slope of the hill, the old Sufi puts up a little tent and brings in two goats. When everyone gets there, he says, “How many of you like this teaching?”

“We all love this teaching!”

“How many of you are willing to die for this teaching?”

An old man says, “I’m willing to die.”

The Sufi takes the old man into the tent — out of sight of the crowd — kills one of the goats, and lets the blood flow out underneath the tent flap and stain the grass. Then the Sufi comes out with a bloody knife. “All right? Who else is willing to die for this teaching?”

Total silence. Then an old woman says, “I’ll die for it.” He takes her into the tent, kills the other goat, blood flows out, and he comes out again with the knife. The people all scream and run away: “Agh! He’s crazy!” And the Sufi writes to the king, “I have one and a half followers.” The half was the man, who didn’t know what was going to happen; and the one was the old woman, who did know what was going to happen — or thought she did.

Ventura: In many of your recent poems you’re writing about death with joy: “Like a note of music, I am about to become nothing.” You write without the one quality that everybody associates with death: fear. Where’d the fear go?

Bly: Maybe I’m just whistling in the dark.

Ventura: But if you’re not?

Bly: Isn’t there a word for something like “the joy of disappearing”? Some people say that’s what a water drop feels when it disappears into the ocean or evaporates on the sidewalk in the sun. I’ve always been interested in joy, but the joy of disappearing . . . [His voice trails off.] There’s a joy in winning the race, and there’s a great joy in losing the race.

The greedy soul is abashed whenever we lose, so the advice of Malamati is: go ahead and lose the race! [Laughs.] But that doesn’t seem to be an American point of view.

Ventura: Nor a New Age point of view. [Laughs.] You keep coming back to the joy of “loss.” It reminds me of James Hillman’s story about when somebody would come to Carl Jung and say, “I just got a new job!” and Jung would say —

Bly: [Laughing.] He’d say, “I think if we all stick together, we can get through this.”

Ventura: But when somebody would come and say, “I just got fired,” Jung would break out the champagne and say, “What a wonderful opportunity!” So it’s a stripping down. What feeds the true soul, over and over in these poems, is something being taken away.

Bly: It’s a little rebuke to the insatiable soul. As your legs get weaker, it’s a rebuke to the rapacious soul that wants to run after things and catch them. It’s a serious fight between the rapacious soul and the soul itself.

Ventura: So they’re different.

Bly: Yes, but not in capitalism! [Laughter.]

Ventura: Give me an example of the “real” soul, the generous soul.

Bly: Joseph Campbell described how he once saw that soul in action: In Hawaii there was a man about to jump off a cliff. A policeman pulled up and, at tremendous risk to his own life, caught the man at the very last second. And Joseph said, “There’s one human being risking his life to save another.” That’s not the greedy soul; that’s the real soul.

Ventura: So where does the rapacious soul come from?

Bly: The rapacious soul has apparently been in human beings since the very beginning. It’s what goes to the neighboring tribe at night and kills the men and kidnaps the women. And a sadness appears on the face of human beings because this has been going on for several million years. My teacher says, “This soul, just for the wink of an eyelash, is willing to destroy the whole world.”

My tongue never becomes bitter because my mouth Keeps holding the grief pipe between my teeth. Go on and conquer bitterness; it’s already too late.

That’s a funny use of language, in a certain way, because I say, “It’s already too late,” but what I mean is the opposite.

Ventura: How so?

Bly: I mean everything hasn’t even begun yet. [A pause.] What are you thinking?

Ventura: I’m thinking of the last verse in “Listening,” from The Night Abraham Called to the Stars:

The hermit said: “Because the world is mad, The only way through the world is to learn The arts and double the madness.” Are you listening?

Bly: When I talk about the world being mad, I tell people, “You won’t believe how bad television is going to be in ten years. You’re going to literally have to protect your children from it.” And we’re not going to be able to change that. The only thing we can do is recognize that it’s mad, and reach inside ourselves and bring out our own genuine madness in the form of art, and then teach our children to do the same. We can bring our madness out to meet the world’s madness! Can we diminish the world’s madness? No way! But every individual or family can bring up some madness of their own by learning the arts. Learn to paint a picture or write a poem.

Ventura: How do you define “genuine madness”?

Bly: If you say to a small child, “Will you draw a picture of a person?” the child goes [gestures scribbling in all directions]. That’s mad, but that’s the way it is. And I think all art is connected to madness — in a good way. Encourage that kind of pictorial madness, and even verbal madness, in your children. Everything I write is mad in some way. That’s fun. But I think people have been trained to be sane, and that’s the worst possible thing in the midst of the stuff we’re dealing with. Some people get mad through alcohol and drugs, but that isn’t genuine madness. I believe a lot in the possibility of art being connected to madness in a good way.

Another source of madness is something like the Mother Conference, in which people meet for ten days and do a lot of work with paint, mud, poems, stories, and ritual. The ones who don’t want to hear unusual truths and become mad will drop out, and gradually you’ll get just the people who are interested in being mad in a creative way. Then you have a union there.

Last year we were at Orcas Island, outside of Seattle, and a man would go up in a big tree outside the dining hall and play saxophone for an hour. That’s a tiny bit mad.

Ventura: American literature has become too goddamn sane. I think the worst thing that’s happened to American letters is minimalism. They blame it on Hemingway, but if you read Hemingway he’s not really like this. In the minimalist way of telling a story, you don’t digress. You just stay on the subject, and there can’t be ruminations; there can’t be anything pretty; you can’t get into description. Minimalism was basically applying the aesthetics of business to art.

Bly: Woooo!

Ventura: The universities bought into it, and the writers bought into it, and the magazines bought into it. Of course, Cervantes would have been totally bored writing that way. So would Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy — in War and Peace, Tolstoy stops in the middle of the story and goes on for fifty pages about history. Then he resumes the story.

Bly: Wallace Stevens, the poet, said, “In excess continual, there is a cure for sorrow.”

Ventura: So that’s where we have to go to survive this era. We’re not going to survive it through sanity.

Bly: No.

Ventura: And we’re not going to survive it through logic.

Bly: No.

Ventura: So we’ve made a suggestion, you and I, a tentative, reckless suggestion.

Bly: Which is?

Ventura: Release — increase — the madness, the rich madness of creation. My brother Vinnie once said, “In order to survive my life, I’ve got to become as outrageous as my life.”

Bly: I’d like to end with a poem by Antonio Machado:

The wind, one brilliant day, called to my soul with an odor of jasmine. “In return for the odor of my jasmine, I’d like all the odor of your roses.” “I have no roses. All the flowers in my garden are dead.” “Well then I’ll take the withered petals, and the yellow leaves, and the waters of the fountain.” The wind left . . . and I wept, and I said to myself, “What have you done with the garden that was entrusted to you?”

I like that, the way the wind isn’t depressed. And the wind says, “Well, OK, I’ll take the waters from the fountains.” And I wept. And I said to myself, “What have you done with the garden that was entrusted to you?”

I’ve seen men weep when they hear that.

Robert and I sit in the rich silence awhile, with echoes of Machado’s words in the room, smelling roses that may or may not be there.