ON SEPTEMBER 11, 2001, there was a knock at America’s door. No one wanted to open it, but History isn’t bashful. History smashed the door in.

The Sun doesn’t usually report on current events, but September’s terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C. marked a turning point for all of us. We put out a call to our writers, inviting them to reflect on the tragedy and its aftermath. The response was overwhelming. As word got around, we received submissions not only from regular contributors but from writers who are new to The Sun’s pages.

We’d already finished work on our November issue, but we scrapped half of it and started over. The pieces collected here were written within a couple of weeks — sometimes a couple of days — of the attacks. As we assemble these pages, during the first week of October, we have no way of knowing what lies ahead. The front door is still in splinters. History is walking around back.

— Ed.

I keep thinking of the time that I flew out of New York with my family, my husband and two young children. As the plane ascended, we looked down upon a sea of clouds, a soft billowing from horizon to horizon, and saw only the two towers of the World Trade Center reaching through them. The twin towers were symbols of human endeavor, of its perplexing scale of risk and accomplishment, capable of towering above the clouds and yet minuscule in that drift of white, viewed from an altitude of thirty-five thousand feet. To look at them that day was a kind of enchantment, the dream of human ascendancy.

In the Old Testament, the people of the plain build a tower to reach God, and it is their common language that makes the construction of that tower possible. God confounds their language; they all begin speaking different tongues, and the tower falls into disrepair.

Our dream of Babel is different. We do not dream of building a tower to God, and only the most fanatical lay claim to such proximity to the divine. We dream of a common language. The World Trade Center was not meant to reach the elevations of God but to find a common language in money. In our dream of Babel, the towers aspired to a world united and engaged in peaceful business, irrespective of the differences of nationality, ethnicity, or religion.

Many commentators compared the terrorist attack to Pearl Harbor, “a day that will live in infamy,” as Roosevelt said. They repeated that phrase, I realized, out of a hunger for language that could rise to the occasion: a longing for truth and beauty; a way of making sense out of senselessness; the clarion call, not of trumpets, but of the human heart. In the absence of any true language, these commentators were repeating the grand responses of the past. For it wasn’t just brave deeds but great language that brought this country into being, great language that banished slavery and won the Civil War, great language that brought about the successful granting of individual rights to many disenfranchised populations. We are silent, however, full of the disaster movies of our own imaginations, the techno-jargon of bureaucrats, the video-game language of modern warfare, full of hyperbole and exhausted cliché. It is not by accident that we have a president who cannot speak, who earns great praise when he manages to recite practiced lines without making some mistake.

It seems quite clear that the coming conflict is one of narratives in conflict. On the one hand, we have the dream of a common language of commerce; on the other hand, we have the medieval dream of martyrdom and religious war in a country that is no more than dust, a country where the average person makes less than eight hundred dollars a year. We can’t go back to the old languages that we have forsaken. In our silence, we should be glad for that: glad that it is impossible for us to respond to bin Laden in equivalent medieval terms. The challenge before us is to find a new language, a language of heart and imagination that honors those police and firefighters who gave of themselves so willingly, so generously, in those ruins, in those clouds of dust. A language that expresses the greatness of spirit that we see among the people on the streets of New York, that we hear in all those phone calls to say words of love to someone, to the world itself, while flying into the fire. A language born of the willingness to be human together on the ground where once Babel stood.

I remember the image of a man fleeing the ruins. Balding, wearing glasses, round of build, he came running out of the billowing dust cloud. The whole world had been bathed in that dust. It covered the ground, a nearby car, and the man himself, from head to toe. He was so gray, he seemed almost a ghost. He had been running headlong, but now he moved this way and that, in confusion, as if uncertain where he was or where he needed to go.

There are many accounts in war of soldiers badly injured and yet still walking, who do not know if they are still alive, who ask, “Am I dead?” This old man, covered in dust, seemed caught on that same threshold of not knowing what was real or whether he was dead or alive. When he saw the camera pointing at him, he put his hand upon his chest, feeling for his own heartbeat, and he said, “I made it! I made it!” With a wry, almost humorous expression, he said, “I’m sixty-nine, but I can still run!” and he turned and walked off, no longer a ghost, but a man again, certain of his own heartbeat, with mischief in his eyes.

On September 11 2001, 36,000 children worldwide died of hunger.

Where: Poor countries. News stories: none. Newspaper articles: none. Military alerts: none. Presidential proclamations: none. Papal messages: none. Messages of solidarity: none. Minutes of silence: none. Homage to the innocent children: none.

— e-mail circulated after September 11

Twenty-five years ago I was in the World Trade Center. From outside, the twin towers looked strangely puny. All decorative elements stopped at the sixth floor. The details and the siting were executed as if the designer was trying valiantly not to make it too overpowering. The long ribs reaching up — seemingly forever — reminded me of the vertical bars I had known at the state reformatory where I taught classes in literature.

I had gone to the World Trade Center to buy (I swear!) some antique Chinese National Railway Sinking Fund Debenture Bonds from (I swear!) Carl Marks and Co. — the biggest foreign-bond market maker in the country. I got off the elevator at the fifty-fifth (or sixty-fifth, or seventy-fifth) floor.

The halls were mustard-colored and smelled of too much money and cleaning and not enough joy. The narrow floor-to-ceiling windows at the end seemed absurdly small. All the doors were dun-colored and had peepholes. When I finally got buzzed into Marks and Co., the clerks lurked about behind heavy glass partitions, counting endless certificates. They never seemed to look out the windows at the stunning vistas.

People who suffer from acrophobia do not suffer from fear of heights; they suffer from reality. Tall buildings are designed to protect our psyches from the fact that we are a long distance from the ground. There’s a reason they don’t build these structures with see-through glass floors and ceilings, although it is now possible to do so. Ceilings are solid; floors are carpeted to disguise the fact that we are walking on cement, steel, and lots of thin air. Windows? In most skyscrapers, they are never to be opened. They, too, are part of the decorative delusion.

The people who worked in and visited the World Trade Center could never see the ground and those tiny people down there as something to which they were connected. They were a thousand feet above reality. The beautiful views of skyline and streets and harbors coming in through the windows were not unlike the pictures projected by a 180-degree film projector: large, idealized, unreachable. It is said that the architect who designed the towers, Minoru Yamasaki, had a fear of heights.

It was only when the shell surrounding their imaginary space was blown away that the citizens of this mangled aerie began to realize that there was only one way to reach terra firma. After the first few bodies toppled from the upper stories, the television cameras pulled back. It was reality TV, and none of us was prepared to see it through to its conclusion.

I will forever be haunted by the vision of those people hanging out the shattered portals of the upper floors of that fragmented building. It is a beautiful wind-swept day, with an achingly blue sky. There are dozens of them waving white towels, flags of hope (the day was so lovely), waving, waiting for help. Those white flags, for some sad reason, reminded me of the scraps of paper, hastily scrawled notes that, they tell us, were found along the tracks where the trains bound for Treblinka, Buchenwald, and Auschwitz had passed in the night.

Many of us were confused by the timing. We thought the big bang would come on December 31, 1999, at midnight. We dreaded it so much so that we invented a computer glitch to give us an appropriate reason to fret. But we were off by more than a year and a half because disasters, like history and love, never come exactly on schedule. Thus, the twenty-first century arrived at 8:45 in the morning, September 11, 2001.

Composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was roundly condemned for saying that the bombing was “the greatest work of art ever.” His words came out sounding more callous than they should have. Those who have followed Stockhausen and his peers know that for them the function of art has always been to skew reality. As such, his take on this act of terrorism is plausible, if crude. Our reality has been profoundly changed by it. We will never see clouds of debris, people in high windows, and bearded men with Middle Eastern accents the same way again.

Jets will no longer be simply a rather crowded box to get us from here to there quickly. You and I will never enter the elevators of what we once called “skyscrapers” without a momentary pause, a twitch of fear.

This new fear of ours goes well beyond structures. Subways? We all remember the sarin gas attacks in Tokyo. Water? They are saying it’s possible to drop something in the water, something invisible, undetectable, that will poison us. The air? How about anthrax or botulism? Food? One of the nineteen hijackers was studying crop-dusting, to seed our fields with new and awful chemicals.

Can there be any end to our fears now? For fifty years, the ecologists have taught us to worry about the contaminants of our milk, water, air. Now, a band of willful men (and our televisions) is teaching us to find dread in every corner.

Let us thus pause for a moment to grieve for the shedding of our innocence, that great American innocence — now infected with this new and deadly particle of fear. We have caught the virus, the one that has for so long permeated the lives of so many overseas — in Northern Ireland, in Israel and Palestine, in Laos and Cambodia, in Iran and Iraq, in Timor and Indonesia, in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Buddhists say that we must be mindful of every bite, every sip, every step, every thought. Thanks to nineteen men who had the arrogance to believe that their god was more important than human lives, we have now all become fully alert Buddhists.

I woke on September 11 to the sound of the phone. It was my sister in Iowa, her voice panicked, telling me to look out my window. I pulled back the curtain and saw the flames and the huge black flag of smoke unfurling over the harbor. I don’t have a television, so I turned on the radio and sat at my desk and watched. Mercifully, I was far enough away that I couldn’t see the people falling. Though I have binoculars, I never once considered picking them up.

Later, at the foot of the Williamsburg Bridge, a couple of hundred people pressed around the knot of police blocking the entrance to the footpath. The cops were apologetic, but firm: No one goes into the city. A ragged flow of people came over the bridge from Manhattan, some coated with gray dust they didn’t even try to brush off. Groups of Hassidim wandered through the crowds handing out bottled water. An Hispanic guy wheeled his Italian-ice cart into the middle of the crowd and started giving his ices away. For hours, we all stood in the hot sun, staring up at the heavy smoke trailing across the perfect, blue sky.

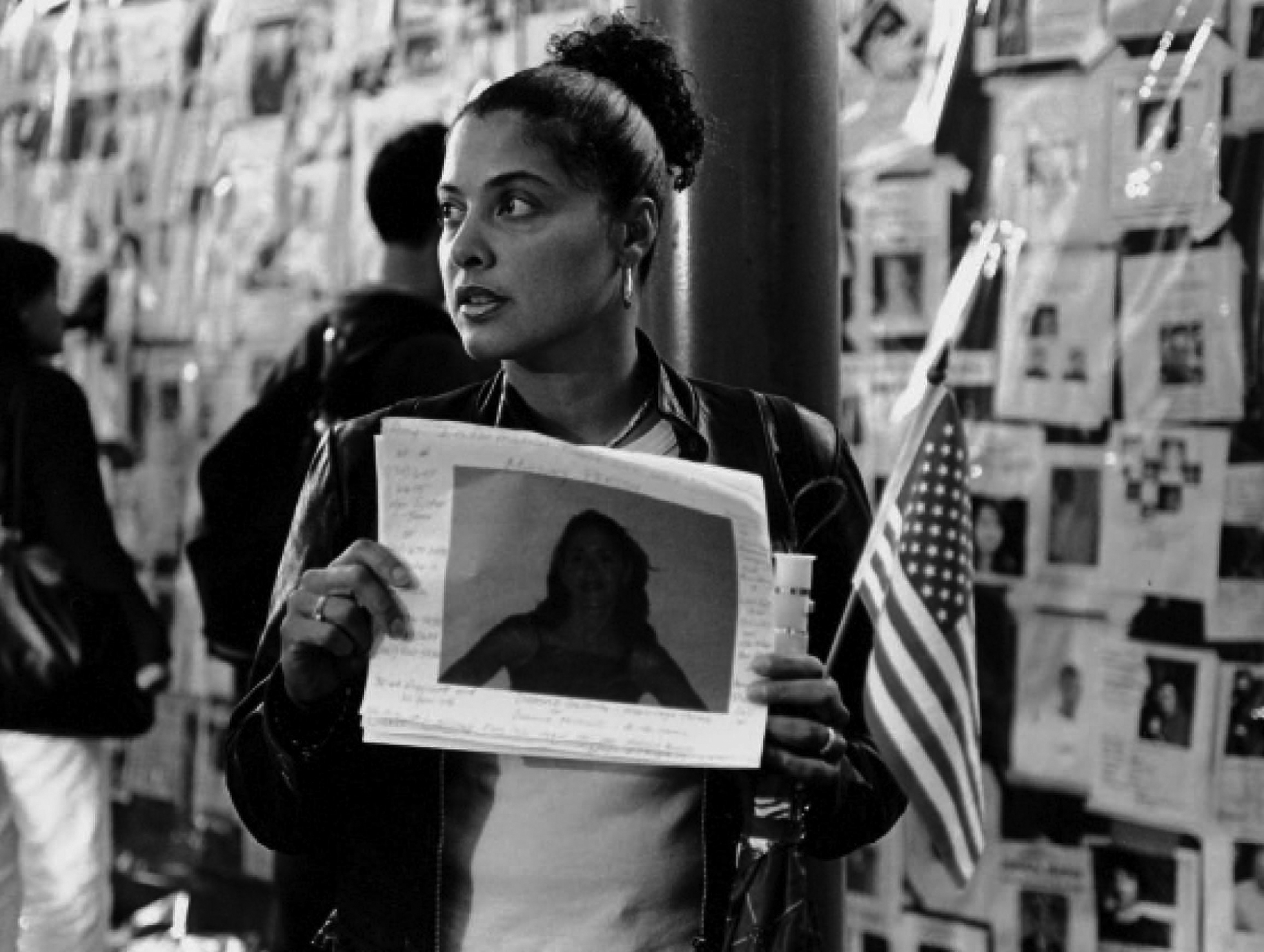

My friend Suzy runs an art gallery downtown, and on Thursday she and I used her business card to get past the police barricades at Houston. There were soldiers manning the barricades on Canal, but we cut through a parking lot and walked south into the carnage. Crushed, burnt cars and emergency vehicles lined some streets, a few stacked two high. Office papers blew around, and photocopied fliers with pictures of the missing covered poles and windows. Men with hoses washed the thick dust from the buildings and streets. Flats of water bottles and boxes of food were stacked on street corners.

We reached serious barricades a few blocks from the disaster site. Through the drifting smoke, we glimpsed the pile of rubble towering over the streetlights.

“Five firemen were just found alive!” a filthy rescue worker yelled, his ear pressed to a cellphone. “Two of them walked away!”

In response to the news, the reporters rushed around looking for someone to interview, and the police and soldiers tightened security. Dust and smoke swirled in the air, and every few moments I had to blink something out of my eyes.

Suzy and I stood around for an hour, and I took a few pictures, feeling useless. There was no simple explanation here, no clues to decipher.

I’ve been back to the ruins again in the past week. I’ve stood in the smoke, smelled the rotting flesh. And I’m terrified that the President’s attempt to make this into a B-grade Western, with an evil villain and a happy ending, will be the death of many more of us.

I was visiting my aunt in New Jersey that morning, and I rode the 8:50 A.M. train into New York City. Three men boarded and announced that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. Heads snapped around.

“Which tower?” someone asked; no one knew. Either way, it meant the same thing: our commute was fucked.

A stop or two later, more passengers got on. It was a jet plane, one of them said.

Impossible, I thought.

We stopped at Summit, where I changed trains. I thought about calling my aunt, who worked at the World Trade Center, but the line at the pay phone was long, and there was my train already. And what would I say: “Get off the phone; an airplane just hit your building”?

On the new train, a man said two planes had hit. Two commercial jets.

“That’s no accident,” I said.

The man gazed out the window at the crisp blue sky and said, “Can’t be weather related.”

He began to tell a story about two planes that had collided over Brooklyn in the 1960s, but he interrupted himself to point a finger against the window. We caught a quick glimpse of the World Trade Center, white smoke billowing off the towers. My aunt worked on a floor somewhere in the nineties, maybe the hundreds, of Tower Two. I’d been to her office before. She could watch helicopters pass by the window during dull meetings.

The train stopped at Maplewood, and an announcement was made that no more trains would go into the city that day, that we should cross the tracks here to get a train back home. People smacked their cellphones into their palms, trying to force them to work.

I studied the train schedule. My aunt had taken the 7 A.M. train, which put her in the World Trade Center at 8:40 or so. We’d talked about my riding into the city with her that morning, but I’d said, “I’m not really a morning person.” Now it seemed a vacuous, stupid remark.

Someone said the Pentagon had been hit. . . . The south tower had collapsed. . . . The north tower had collapsed. Was I supposed to believe any of this?

An elderly woman standing near me said to no one in particular, “I hope my husband is watching the TV and thinks to call and cancel my doctor’s appointment in the city.”

The train I was waiting for arrived. Some of the passengers already on board had seen the plane hit the World Trade Center. They had seen it. This was no longer a vague rumor.

No one talked much, except one man who abruptly cried out, “Thousands of people just died in the last few minutes!” Everyone kept reading, the way commuters do. Even those who had seen it were reading.

At my aunt’s house, there were nine messages on her answering machine. One was from her father-in-law in California. He said my aunt had called him, and she was fine.

But I didn’t really believe it until she got home that night and we stood in the kitchen, our arms around each other, crying, holding on.

“New York, the capital of the twentieth century” — so Norman Mailer once described his city. The proof is in the architecture. In the 1930s there was no skyline like New York’s. By the 1990s the New York skyline, and the way of life that goes with it, was mirrored by every major city in the world. The Manhattan-style skyscraper became the most visible global symbol of economic and political power, and New York became the nerve center of humanity’s commerce. On September 11 two great buildings of the world’s economy, New York’s tallest, 110 stories high . . . we watched them collapse, dissolve, in mere seconds. The intended symbolism could not be more clear: what was strong in the twentieth century is fragile in the twenty-first; what seemed invulnerable is vulnerable; the very things that were designed by our strength, and for our convenience, can be transformed into the implements of our destruction. The World Trade Center and the Pentagon — the twenty-first century has announced its terms by successfully assaulting two prime symbols of the twentieth. Daily American life, from now on, will require a far greater capacity to endure uncertainty and fear. We don’t yet know if the American Dream, with its cocky mix of audacity and naiveté, can remain viable amidst the forces of chaotic instability that seem to be the twenty-first century’s signature.

Granted that the World Trade Center, as architecture, expressed the buildings’ functions all too well. Those monolithic rectangles were crude, massive, unimaginative expressions of raw, selfish power. But those buildings were inhabited by individuals who, like most people, were trying to resolve the contradictions of their dreams within the humble, difficult, never-finished task of earning one’s keep and doing one’s best. How much love, and effort, and laughter, and hate, and regret, and bravery, and longing, and cowardice, and certainty, and dullness, and ambivalence, and sweetness, and greed, and illusion, and generosity, and truth, and memory, above all, their private special memories . . . how very much died with each of those people that day.

And the deluded cruelty of the terrorists — that, too, is part of us. For it is human to believe passionately and mercilessly; to sacrifice oneself for an ideal, and to blind oneself to the grotesque results. More than anything, it is horribly human to fail to see the Other as equally valid, equally human. And how much delusion and cruelty will those terrorists, in turn, generate? On the night of September 11, even a man whose opinion I value highly spoke in the most extreme terms of annihilating Islam. Horror begets horror. For it is also human, in times of crisis, to allow the lowest and ugliest to set the terms. So Hitler set the terms by which America justified the atomic incineration of a quarter million civilians at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. No nation that committed such atrocity can claim a moral high ground on terrorists. Which cannot excuse anyone’s terrorism against our innocents. None of it is justified. And that is human, too: to become so intoxicated with the unjustifiable that our very intoxication becomes our justification. How terrible can be the allure of the unspeakable, and how human it is to surrender to that allure.

It remains to be seen, as I write, what America will do. A military response is essential, but it brings to bear an ancient question: how can justice be balanced by mercy? If we fail in justice, we cannot survive. If we fail in mercy, it won’t matter whether we survive. As was said by the prophet whom we name as the fount of our civilization: “What does it get you, if you gain the whole world but lose your soul?” So America is about to be tested, and to test itself, by the form and extent of the unquestionably necessary violence to which we must resort. What America does now will set the tone and pace for the history of the next fifty years.

In Stephen Mitchell’s translation of the Tao Te Ching, the thirty-first passage reads:

Weapons are the tools of fear; a decent man will avoid them except in the direst necessity, and, if compelled, will use them only with the utmost restraint. Peace is his highest value. If the peace has been shattered, how can he be content? His enemies are not demons, but human beings like himself. He doesn’t wish them personal harm. Nor does he rejoice in victory. How could he rejoice in victory and delight in the slaughter of men? He enters a battle gravely, with sorrow and great compassion, as if he were attending a funeral.

And yet fury also is necessary, or you cannot win. Such a paradox used to be called “the human condition.” We are learning again that all our sciences, all our achievements, have not and will not free us from the condition that we are contradictory beings who cannot satisfy one need without denying or giving short shrift to another, equally essential need.

Is a national response within the Tao Te Ching’s terms possible? Of course. Acting with great audacity and compassion during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Kennedy administration faced the gravest threat and prevailed with virtually no violence — though it was ready for the greatest extreme of violence if its gambit failed.

Is such a natural response likely now? As the firefighters and police of New York City proved, rising nobly to the occasion is also one of the great human possibilities, and we cannot prejudge that possibility for any leader, especially our own. But no action will solve for very long the dilemma we find ourselves in. It would be delusional to think there’s some ultimate solution. No matter what we do, the twenty-first century has announced itself in the starkest conceivable terms by how quickly, on September 11, we accepted this fact:

We know we’re at war, but we don’t know precisely with whom.

That’s the twenty-first century.

But even if we identify the perpetrators and supporters of these gruesome acts, and even if we destroy them, our satisfaction will be temporary. It is one thing to war against a nation, for you can defeat a nation; it is quite another to war against a subculture, a movement that spans many nations and cannot be ultimately confined or pinned down — a movement that uses the very instruments we’ve invented and depend upon: weapons, communications, financial arrangements, and tactics concocted by the ingenuity of the West. The biological, chemical, and atomic devices that we fear most in the hands of others — they are our creations. And the fact that others can wield them is the result of our greed, arrogance, and short-sightedness. This does not in any way mitigate the moral culpability of our adversaries; but it is a fact as much as a metaphor that they threaten us with the devices of our own paranoia and ambition. And that, too, is the twenty-first century.

Whether it is global warming or terrorism on the monstrous scale of the World Trade Center, the fundamental dynamic of the twenty-first century has announced and revealed itself: the underlying enemy of the Western nations will be the chaotic unleashing of the very forces that the West so proudly and hopefully created. Insofar as those forces were the expression of our selves, we will be fighting ourselves. For our adversaries, on their own, have invented nothing that could touch us. If we are wounded again (and we almost surely will be); if we are somehow defeated (and even that is a possibility) — it will be by the tools we created and the forces we unleashed.

That, above all, is the twenty-first century.

At present, most of humanity lives in poverty and ignorance, under the constant threat of violence. Roughly three out of five children receive no education at all; these kids have no way of investigating propaganda, and are easily molded. We will not be safe until they are safe. Until they’ve achieved a modicum of security, education, and prosperity, they’ll have every reason (emotionally if not logically) to hate us, and no reason not to attack us. We are learning the terror of fighting an adversary who has nothing to lose. Until they have more to lose than their lives, they’re not going to quit. Which is why the satisfactions of retaliation will be fleeting — however necessary retaliation, at the moment, certainly is. Killing one of their leaders and a thousand of his followers won’t change the basic equation. Nothing can ultimately “win” but a foreign policy that has as its ultimate goal the well-being of the disenfranchised. Until that is achieved, it is only human for the wretched of the earth to take satisfaction in making our lives equally wretched — and we’ve given them the tools to do so.

Fear and rage are natural but beside the point — for acting out of fear and rage will only increase the chaos. What is necessary is vision, compassion, and courage. Nothing else can meet and tame the dragon-like energies of the twenty-first century.

Is this the first event of World War III, a war unlike any before, to be fought in ways unlike any before? It may be. As I write I feel like I’m whispering, because in such a time all words that are not shouted feel like whispers — small breaths of sound spoken in the dark, their meanings tentative and incomplete. It is very late, it may be too late, but still I propose a toast and raise my glass:

To the compassionate and brave.

Michael Ventura’s essay also appeared in the Austin Chronicle.

“God bless America” was painted on the rear window of an SUV in front of me in traffic today. The driver made a sharp right turn without signaling, flaunting his conviction that this is a free country. A near victim of his rugged red-white-and-blue individualism, I slammed on my brakes, only to be jolted back into the memory of the four hijacked planes, right here in the country where I live. In two hours on a sunny, bright-blue morning, the media endlessly repeated in their collective soundtrack loop, “our lives were changed forever.” “Things will never be the same again.” “America has lost her innocence.” The opening scene: the repeated image of a plane flying into a tower of the World Trade Center.

We have been lucky up until now, free of tragedies on this scale, which happen all the time around the world but are relegated to sidebars in our papers, a two-sentence reference in a television broadcast, the hundreds of thousands lost to war, famine, natural disaster. We do what we want here, travel at will, choose from ten brands of cereal, and shop till we drop. After all, we are Americans. That has been our legacy, our shield against disaster, our illusion.

Our President has promised to protect us and save us from Evil, with a capital E, which now seems to have been located somewhere in Afghanistan. He has promised to make things safe again, the way we have had the luxury of imagining they always were. He has asked us to join him in this belief. We will toughen ourselves, harden our borders, galvanize our troops, and send our young men and women off to a war far away. There will be sacrifices, we are warned, but sacrifice we must, at least long distance. This is who we are, our President tells us. This is what it means to be an American. Scripts in hand, we are all unwitting actors in an astonishingly gruesome movie-of-the-week. The voice-over begins; the opening credits roll. The film, as of yet untitled, is destined to become a classic.

A day after the attack, I learn about friends of friends dead in the planes and the buildings. I comb the lists of the missing for my estranged fiancée’s name, and am relieved when I don’t find it.

In the morning, the sidewalks of San Francisco are full again, and a light gray fog sits over the bay. The newspapers are questioning what we could have done differently. There’s a world of consoling to do. The blood banks won’t take my blood. We won’t know the body count for a week, but they’re already talking thousands. Colin Powell says we will respond as if at war, and the Chronicle runs heartbreaking stories of doomed passengers making last phone calls to husbands and wives. The crowds are back in line at Peete’s Coffee, and there is even a little laughter, but not much. We’re preoccupied. America has been at peace so long that we elected George W. Bush president, and now we have to make do.

I read all of the editorials. Most bellow for revenge, some pointing to the perhaps twenty Palestinian children caught on camera dancing in the streets, no doubt before being told to go back inside. A couple call for reason, knowledge before action, remorse for the victims. The only one I really like is in the Washington Post: it begins, “What to write in the face of something so horrible? It defies you.”

Nobody knows what’s going to happen next. The first assault will almost certainly be on civil liberties. America will choose safety over freedom.

I returned from Palestine just ten days ago. People call to say, “I bet you’re glad you’re not there right now.” The presumption being that a white American in the West Bank would be pulled limb from limb by gleeful Palestinians, who would then paint themselves with my blood.

At night I dream of Islamabad. I consider joining the army.

I’ve never gotten so many e-mails. Friends of friends spam me indiscriminately; it’s urgent that everybody get their point across. The full spectrum of human emotion has found its way into my inbox. I get letters about what we plan to do to those “towel-headed niggers” and “camel-jockey motherfuckers.” And I get letters imploring that we not hurt anybody; there’s been enough killing. I don’t know which bother me more. Everybody complains about the media, the endless video loop of flight 175 crashing into the south tower, the explosion, the Asian newspaper reporter in a bright pink dress screaming behind a car.

Buried in an article in the New York Times are two sentences saying that Congress has granted the INS authority to deport suspected terrorists without a trial. Where shall we send them, Cuba or Afghanistan? I don’t fret over civil liberties; they are a thing of the past.

I hear complaints about the copious number of American flags. The local communists say the flags equal violence. In Berkeley, a man is asked to take down his flag.

I have decided against joining the army. I would not be a good soldier. It’s been eleven days since the attack, and I am no closer to grasping the situation. Nearly seven thousand are dead in Washington, D.C., and New York City. We’re going to attack Afghanistan. The peace pundits worry about fixing the root of the problem: the evils that America has done, a million dead innocents in Iraq, 3 million occupied Palestinians, missile strikes on pharmaceutical companies in the Sudan. The list goes on and on. America is responsible for enormous amounts of grief. The Susan Sontags and the Noam Chomskys of the world tell America to look inside itself. This, of course, is not going to happen. What conclusions would we draw? We suck. More bombs, please. Kill us: we deserve it.

In the end, we won’t know until it’s over what the right decisions should have been. Perhaps not even until we are picking through the irradiated landscapes for scraps of early decisions made, cataloging and filing our glow-in-the-dark mistakes. Historians in spacesuits will then state with absolute certainty, “They never should have assassinated Archduke Ferdinand.” Everything else is just speculation.

The most striking image for me in all the hours of television I watched on September 11 was the picture of a man and a woman, both African-Americans, both dressed in business suits, both completely covered in gray ash, fleeing hand in hand, their mouths open in gasping Os. Their ashen faces and bodies, their postures of woundedness, grief, and confusion made me think of images I’ve seen of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the moments and days after we dropped atomic bombs on those cities.

Some people have been saying the American age of innocence is over. What is over is the American age of impunity. Now we suffer as the rest of the world has suffered.

Seeing those two people staggering through the rubble of the World Trade Center also made me think about the saturation bombing and the napalm we loosed on Vietnam, and the TV pictures of our relentless bombing of Baghdad. You remember those squeaky-clean images of our “smart” bombs falling, how we sat at home and watched on TV as Generals Powell and Schwarzkopf explained to us the technical details of our devastation of Iraq.

What unites all of these images of human suffering, these acts of carnage and devastation, is how far away all of them were, just pictures to us, TV images to be watched and analyzed with a cool and pristine fascination.

Not anymore.

My daughter stood on the Brooklyn shore of the East River and watched tens of thousands of ash-covered New Yorkers stream across the Brooklyn Bridge like refugees. This timeless image from Germany, Japan, Vietnam, China, Iraq, Bosnia, Ethiopia, Rwanda, this image of dazed and confused refugees fleeing — this image has come home.

No amount of macho, saber-rattling bravado from politicians and generals can save us from the images of September 11. We now know what it’s like to have done to us what we do to others.

Let us pause a moment.

Let us ponder what unleashing yet another wave of violence will do to continue this international curse of war on civilians.

Let us act now to stop the carnage rather than perpetuate it.

I sleep with my daughter’s plastic rosary beads wrapped around my fingers. My grandmother used to carry rosary beads around with her all day long; she had lost her only child, her son. I have lost my neighborhood and some of my faith — a friend’s father, too. Frank De Martini, an architect for the Port Authority, stayed behind in Tower One to help his coworkers escape.

The site of the World Trade Center is two blocks west of our apartment building. We can see the skeletal hulks from our front door. At night, we hear the rumble of bulldozers moving heaps of steel around. The noise runs through our dreams, like the sound of tectonic plates scraping against each other. Spotlights from ground zero project shadows onto surrounding buildings. National Guardsmen stand outside our door. Our street has become a parking lot for police and detectives, their Chevy Suburbans lined up as if in a used-car lot. On the weekends, streams of people descend on the neighborhood to see what’s left behind.

Smoke continues to rise from the rubble. My children are amazed at the relentless, stubborn nature of fire. At night, we feel a scratchiness in our throats, and in the morning, depending on the direction of the wind, an acrid smell assaults our senses. We hurry out of the neighborhood to work and to school.

It seems impossible to live so close to ground zero, but we are determined to stay and go on with our lives. My children’s schools have been turned into command centers; they now attend crowded, makeshift classrooms in the Village and Chelsea. They are glad to be back among friends, though only half of my daughter’s classmates returned: most of them lived in Battery Park City, which is entombed in debris. Some families have vowed never to come back.

Our grocery stores are open, our phone has come back on after twenty days, and our parakeet, who made it through the two explosions and the collapse of both buildings (I had left our windows open when I fled, not anticipating the worst), still sings. But don’t be fooled; it requires stamina and fortitude and a partial blind eye to live here. The Twin Towers were integral to our everyday existence; we walked and strolled and biked through their corridors and plazas. And so I sleep with rosary beads, thinking of the dead, waiting for the neighborhood to recover.

I smell something burning, though all I’ve done is light a candle to honor the thousands who are dead. I smell the familiar odor of my mother’s scorched string beans in the copper-bottom pot. I smell the building blazing beside the Grand Central Parkway while I watched in awe from the back seat of my family’s aqua-and-white 1954 Chevy. I wanted to scream, “Slow down, Dad!” I wanted to see the bones of a building, its breath, to see how things are underneath, how they end. But he just kept clicking his gold-and-onyx ring on the pale gray steering wheel, the ring he’d found behind the radiator in our new apartment. “Wow!” he’d said, a rare exclamation from this man, whose silence burned steadily from behind the barricade of his newspapers every night. A silence born of disregard, I thought then. (Of fatigue, I believe now.) I wanted to topple his newspapers, slam my fists into them, make him see me. I am glad he didn’t live to see New York, the city of his birth, burn, the fiery towers crumble.

So many have died. Our usual self-absorption blows away to reveal grief, a tenderness. Strangers say, “I’m sorry,” for next to nothing — almost letting a door close, almost cutting in line, almost brushing someone with a shopping cart. So many other almosts have lined up: “I was late to work that day.” “I took the elevator to the basement to buy Altoids, because I just gave up smoking.” I recall the “almost” of my son’s near death in Peru six years ago. I feel again what it was to almost lose him, my heart charred until I saw him alive, on crutches, tears in his eyes at a safe, busy airport, and how I thought I’d always shine with my good fortune. The lucky mother.

On my way home from town, I stop my car and get out to look at the newborn lambs at Mr. Gould’s farm, their umbilical cords, black and thin, still dangling from pink bellies. I stare into the eyes of one tiny guy propped up on his shaky new legs and remember how the God of the Old Testament found the odor of a sacrificial beast “pleasing.” Standing on the road there, my car still running, the radio on low, I have no idea which god to kneel before, nor what I can truly offer to this burning world but to slow down and see it.

Since Congress has now authorized the president to spend as much as he sees fit and to punish whomever he likes, it seems important to request a deliberative pause to consider what a “war against terrorism” means and implies.

A “network” is any several people who align themselves for a common purpose. Tim McVeigh and Terry Nichols (and three others the government could not make a sufficient case against) were a “terrorist network” pursuing a vengeful agenda. What could soldiers or bombs have done to inhibit their capacity to act? And this occurred in our own country, where we speak the language and spend more on domestic intelligence than many countries spend on their entire economies. What makes us think a “war” will be more successful in places where we are constrained by enemies and political realities; where we cannot put espionage agents on the ground and do not know the language, customs, and terrain?

It is an understandable impulse to desire vengeance when hurt, and it is in this sense that I understand many of the declarations of the President and Congress. Nevertheless, one must ask: Does retaliation serve the best interests of our people? If not, what might? It appears that bin Laden secreted “sleepers” into America who lived invisibly until they were activated to perform a task. The nineteen men who so traumatized us did not fit our comfortable profile of addled and “brainwashed” fanatics. They were organized, multilingual, educated, technologically proficient warriors of fixed purpose, their cover sustained for years before they sacrificed themselves. Knowing what they cherished enough to die for would be the most reasonable place to begin any counter-terrorism response. Lacking that knowledge, what logic indicates that military campaigns in the Middle East will make us safe from such suicidal agents and not simply inspire new terrorists to replace those who have fallen?

Unfortunately, when Osama bin Laden asserts that America has little regard for the interests and lives of Muslims, he has ample evidence to bolster his claims. He can remind Muslims how their cousins in Eastern Europe were denied arms to defend themselves against Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing, and then bore the brunt of his genocidal retaliation when we initiated our bombing of Yugoslavia. Impoverished Palestinian citizens in Israeli refugee camps would need no urging to believe that the United States supports Israel too unequivocally, that it ignores how egregiously — or even illegally — Israel behaves toward them. It is tragically easy for bin Laden to offer himself as their fist.

In Baghdad alone, he could point to the two hundred thousand civilians who died and the millions who suffered, as we are now suffering, from our bombing of a major metropolitan area. He can cite UN estimates that an additional five hundred thousand children have died of an epidemic of cancer from the million uranium-tipped shells we fired there, or from diseases related to our destruction of the civilian water systems. We make it too easy for bin Laden to be the avenger for their anguish and rage.

People with something to live for are not eager to commit suicide. We must attend to the grievances of ordinary citizens in the Middle East if we ever hope to sever their connections to the thugs claiming to represent them. Bin Laden argues that the West is anti-Muslim. What could serve his interests better than further violence against already traumatized people?

A “war against terrorism” has a nice ring, but let us not misunderstand that what is being described is a war against ideas and intentions, and these are not targets that can be bombed or burned away. This is a war for the “hearts and minds” of people we have underestimated and ignored for too long. We made a tragic and costly mistake in Vietnam by proceeding in ignorance of the culture, belief systems, and resolve of those we were determined to vanquish. I pray that we do not hurl ourselves into the same abyss again. It is not the way to honor our dead. It is not the way to live.

I follow a spiritual teaching that advocates peace, mercy, and understanding. I lead poetry workshops for everyone from corporate employees, to prisoners, to at-risk kids. I am against the death penalty. Though I’m not a vegetarian, I do not eat mammals or wear fur.

But, in truth, I have a warrior heart. Had I been born in a different time, I would probably have joined the military. I have a fascination with JAG, a television show about military lawyers, which I watch religiously. I know this warrior heart is what attracted me to my husband — a Republican, for God’s sake. I chide him for his inflammatory rhetoric about the “war on terrorism,” but a certain part of me is marching to the same drum. A certain part of me wants to know if there is somewhere a forty-five-year-old woman can sign up, grab a rifle, and put on a pair of combat boots.

I do not feel the need for revenge, but I do feel — suddenly, urgently — the need to protect my child, my brother’s children, my neighbors’ children. A way of life that just yesterday seemed to me shallow and pretentious now seems unbearably poignant and precious. Our tidy lawns, our clean, smooth streets, our busy little children, our concerts and meetings.

And yet I know the futility, the vanity of violence. What will it get us? Pain and grief.

On Sunday, I go to church. During the service, the minister reads from the Koran, and, like everyone else in church that day, I pray for peace, peace, peace. I say prayers of gratitude for the survival of my family and friends in New York and send thoughts of comfort and love to those who were not so fortunate.

On Monday, my husband’s testosterone level is just about through the roof. People send me e-mails exhorting our leaders to bomb the Afghanis with butter, love and VCRs. I receive at least four copies of a petition to the President for peace. These messages resonate in a deep way, but when someone else e-mails me a picture of the Statue of Liberty with her middle finger held aloft and the caption, “We’re coming, motherfuckers!” that message resonates as well. I laugh and forward it to my warmonger husband, knowing that my peaceful, spiritual friends would be appalled.

For some reason, I don’t sign the petitions for peace. I also abstain from joining my husband in his rants for revenge. Instead, I do what I have always done when I need to find solace: I meditate. I write poetry. I gather with the people I love. A couple of weeks later, when I visit New York City, I notice a pregnant woman, I watch children playing games, and I listen to the multitude of tongues on the streets. I take my peace where I find it.

9/13

I remember suddenly that I have always hated the World Trade Center and often imagined how Manhattan would look if it were gone. Before those buildings, the skyline of Manhattan resembled a recumbent woman. The twin towers looked like two tusks growing out of her legs.

If the attackers had flown two empty planes at 3 A.M. (when all the cleaning women were gone) into the empty World Trade Center — and sent a woman dressed in white to warn the security guards to leave — I would have agreed to it.

9/14

One child asked her mother, about the disaster: “Was the pilot blind?”

9/15

A student in the school where I teach is carrying a tennis racket. “This is my Afghani-beater,” he explains. Two other students laugh.

While I am reading The Iceman Cometh in the library, tears begin falling from my eyes. I’m not sure if I am “crying,” but I am certainly flowing with tears. I don’t feel sad. I just feel my eyes are being washed out.

9/16

The American flag is most unlovely. It doesn’t look like the flag of a nation but of some manic department store.

It is the only flag in the world that is cumulative. It began with thirteen stars, and now has thirty-seven more — as if flags were a game and the one with the most points wins.

9/17

This is not terrorism. Terrorism is a particular strategy: A group attacks a civilian target, for a known purpose. A communiqué conveys the meaning of the act. When a suicide bomber attacks Tel Aviv, it is clear what he wants. Hamas accepts responsibility for the bombing. Their demands are known.

This is a new act. I call it “personal-enigma warfare.” “Personal” because of the small number of people involved. To destroy the entire World Trade Center, nine or ten people were necessary. This is the amount of people at a dinner party. “Enigma” because of the mysterious nature of the attacks. No one claimed responsibility, and no one made demands. Furthermore, the people involved are now deceased. We can investigate their associates and interview their friends, but we will never comprehend them.

Never before has a group of dead people begun a war.

9/18

I listen to talk radio as I wash the dishes. Here, deep in the Adirondack Mountains, stations drift into our range, then migrate away. I hear dissociated phrases:

“I’m not telling people to beat up Arabs, but . . .”

“The Crusades . . .”

“It’s time we finished them once and for all . . .”

9/19

“It’s him: Osama bin Laden!” a teenage boy says, pointing at me. I am walking down Main Street. I examine the “Wanted Dead or Alive” poster of bin Laden taped to Brio’s Pizzeria; he does look like me.

— Sparrow

After the September 11 disaster, I decided to fly back east to see my folks. I was long overdue for a visit, and, given the world situation, it seemed important to be with family. My parents are both seventy-five years old, staunch Republicans, Protestant, middle-class, avid bridge players and golfers.

I called my mother to tell her I was coming.

“Do you think it’s safe?” she asked.

“Yes,” I answered. “I’m not scared.”

“It’s terrible what’s happened, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” I said.

“They’re cheering in Palestine and Newark,” she added.

“Can you believe it?”

“Not everyone is cheering, Mom. Most people aren’t.”

“They need to wipe them all out,” she said.

“Who?”

“Everyone who has done this to the United States. All of them.”

I didn’t reply.

“Your father is down at the golf course practicing his marching. Seventy-five years old, bad heart, bad knees, bad eyesight, and he can’t hear a thing. He thinks he’s going to join the United States Army. I told him he was nuts, that the army wouldn’t want him, but he’s ignoring me. Can you believe it?”

“No,” I said, but after I hung up the telephone, I imagined my fragile, bald-headed, stooped father, marching back and forth along the country-club fairways, readying himself for war.

It’s the end of summer. Everything is changing.

Last night, I had dinner with a friend, and we struggled to keep our promise not to talk about IT. I was driving home when the rain began. I turned on my high beams and squinted into the darkness as the trees flew past. In the headlights, I saw frantic movement on the ground ahead. Tiny white frogs scattered in terror, as though the light itself were a physical force. I slowed to five miles an hour, my car inching through rain, my hands tight on the steering wheel. I thought, Please, dear Lord, don’t let me run over any of them. Please, please, please, don’t let me kill anything.

September 11 was my wedding anniversary. September 11 was my friend’s thirtieth birthday. September 11 was the week before Rosh Hashanah.

A week earlier, on the morning of September 11, another friend walked with me to Alewife Pond. It hadn’t rained worth a damn for weeks. We examined the dry soil and moisture-stressed trees, tisked at the low water level and discussed global warming. Then we decided to get in our cars and go back to her house to examine a tiny pond she’d dug to hatch dragonfly larvae.

I started my car’s engine and pulled out onto the road. News came on the radio. I looked at my watch: 9:30. It should have been classical music. I listened. My heart began to pound wildly. I pulled over and caught my breath, which had become trapped in my suddenly tight chest.

As I climbed out of my car at my friend’s house, I could tell by her smile that she hadn’t heard. I took her hands in mine and repeated what the announcer had said. She looked at me in disbelief. Shaking her head, she led me to the dragonfly pond. I gladly followed, in a wordless agreement to avoid this new world for a few moments more, to remain anchored in the banal flow of the everyday. We examined the pond. She spoke about the tiny, valiant pump at its heart. We admired the long, flat rocks that rimmed the cavity. We discussed the hours of labor it had required. Then we went in for coffee, turned on the television, and reeled in horror.

For days, I had no words for it. Then the dead on their cellphones gave them to me: “I love you,” they said as they vanished into creation, and finally I wept.

“I love you. I love you. I love you.”

This is transcendence, these words that ensure survival beyond the shadow of this life.

In elementary school in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, during World War II, we were taught to conclude our singing of “America the Beautiful” with the following refrain:

America, America, God mend thine every flaw, Confirm thy soul in self-control, Thy liberty in law.

Written by Katherine Lee Bates upon viewing the country from Pikes Peak, this song of love to the United States has been played frequently on the air since September 11, but to my knowledge without this refrain, though these are the sentiments we need most now.

A year ago, I sat in a movie theater watching the film Gladiator, which went on to win the Oscar for best picture. The film opens with a battle scene: the Roman Army slaughtering some vastly overmatched foreign force. It was difficult not to feel roused by the spectacle, which was, in the manner of Hollywood, elaborately choreographed and gorgeously filmed. A number of moviegoers cheered as flaming arrows sailed toward the enemy and Russell Crowe leapt into the fray with his broadsword.

I thought about this scene as I listened to George W. Bush’s address to the nation about the recent tragedies in New York City and Washington, D.C. He stood tall in the well of the Senate and called for imperial might to visit ruin upon the savages. And the audience — the Congress — applauded wildly. Their reaction was, in a sense, typically American, by which I mean: almost entirely devoid of self-examination, true Christian humility, or respect for the tremendous sorrow of our current circumstance.

It is natural for Americans to feel rage over the attacks. But beneath the tawdry jingoism that has swept the country lie far more complex emotions. We’re scared, for one. As a culture, we’re not used to the sight of our own blood. Our emergence as the lone superpower has endowed us with a bully’s false sense of invulnerability. If a handful of zealots with X-acto blades can do this, we think, what’s to stop them from blowing up my office next?

I also believe that Americans feel a suppressed sense of guilt. We know that we’ve been living high on the hog while much of the world goes hungry and dodges bullets. We know there is something inherently immoral in our decadence, something pathological about a culture of citizens who plunk down eight dollars to cheer at fake breasts and fake genocides.

And so our leaders, to assuage our fear and to obscure our guilt, beat their chests and vow revenge. The problem is that a military response to these attacks will, in the end, invite further attacks. Terrorism, after all, is the language of violence. One side kills, the other side kills. The news we receive from Israel and the West Bank should have taught us this by now. The only way to stop terrorism is to attack its root cause, which is extremism. And this includes our own extreme policies of economic hegemony. In times such as these, the Osama bin Ladens of the world make for easy scapegoats, but they are merely demagogues exploiting the poor and aggrieved.

America is never going to be the same again. This has become a kind of national mantra in the uneasy weeks following September 11. And I still hold out hope — a dumb, human hope — that this prophecy might bear fruit. We can, as a nation, forge a new national identity, one marked by an intolerance for all forms of human suffering. But this will happen only if we begin to recognize our own failings: our profligacy, our deification of the wealthy, our support for corrupt regimes. Jesus was an indigent radical who condemned violence and preached a revolutionary gospel of love. He was right. If we are blind to our own sins, we are doomed.

September 11, County Galway, Ireland

When Nicole started the engine of our little rental car, the radio was saying, “— terrorist attack in New York City.” We looked at each other, round-eyed. As she drove, we listened, inarticulately punctuating each new piece of information with “Fuck! Fuck!” When I heard, “The Pentagon is burning,” I started to cry.

What does one do, several thousand miles from home, when the people at home need blood, need support, need condolence beyond all imagining? Where did I belong?

We drove blindly through world-class scenery, too stunned to notice it. We came to Clifden, a hillside fishing town I loved, but instead of driving up the Skye Road to the castle, we parked and found a pub with a TV.

Inside the bar, I stood staring at the televised flames and smoke covering the top of the skyscraper. I, who have never owned a television and rarely watch movies, kept thinking it was just special effects. For me, the worst moment was when the camera zoomed in on a man waving his handkerchief out a window — as if that could help, as if all he had to do was let people know he was there, as if there was anything that anyone could do.

I usually don’t even think of myself as an American, but after seeing those images, I could not stop crying. My parents are British, and I maintained dual American-British citizenship until I was eighteen. Yet I knew the World Trade Center towers, had once lived within sight of them. I had friends in New York and had often taken that flight from Newark to San Francisco. Though I never would have expected to feel any support for or sympathy with the Pentagon, the image of it broken and burning horrified me. I felt almost guilty for the times I had protested outside of it, as if I’d somehow helped cause the destruction.

Despite my newfound allegiance, I was not one bit reassured by the televised image of a nervous George W. Bush promising to “hunt down and punish” the terrorists. Great, I thought, more death.

But then, what could he possibly have said? There’s little that anyone could say that would have helped.

September 14, County Cork, Ireland

The Irish had declared a national day of mourning, and not one single business was open. For us, it was becoming a day of fasting, as well, since we couldn’t find anywhere to eat.

The Irish papers were filled with news from America. More than two hundred Britons had been lost, and an unknown number of Irish, not to mention Irish Americans like the chaplain for the New York Fire Department, who had been crushed while giving last rites to a firefighter.

I slept in the car while Nic drove, and when I woke, we were outside a huge church where a memorial service was in progress. So many cars lined the streets that we had to park a quarter mile away, and walk back. People were clustered outside, listening to the service being broadcast over a speaker.

The doors to the church stood open. When I squeezed in between the bodies in the entryway, I glimpsed the crowded pews and the people standing in the aisles. Hundreds and hundreds of light-haired, fair-skinned people had put on their best clothes and quietly filled the enormous church in the middle of a Friday afternoon. I kept thinking, Whenever two or more of you are gathered in my name, I will be there.

The congregation recited the responses in unison. I knew none of the words, but even if I had, I wouldn’t have been able to speak; I could hardly breathe. Over and over, I prayed, Help us. I thought, Thank you.

September 18, Stonehenge, England

When I’d last visited Stonehenge, about twenty years ago, there had been no fences, no gates, no buildings, and no entry fee. Not even a sign: there were the stones on the wide, grassy plain.

Now the henge looks smaller, standing amid a huge fenced-in area and flanked by a parking lot, a turnstile, a gift shop, and the inevitable tea room. Several tour-bus groups of Germans and Americans milled around, distracting us. Still, we were delighted.

Nic did sketches of Stonehenge from many different angles while I stayed in one spot, gazing at the heart of the henge. To my amazement, I had that rarest of travel experiences: a sense of belonging. Looking at this ancient structure, I thought about the generations of visitors who had come to look at it before me. My own parents had seen it, and their parents, too. Probably every generation of my family for hundreds of years had traveled there to look and wonder. Did the original builders know how long their work would last, how far their intentions would echo into the future? The World Trade Center towers had crumbled, but Stonehenge remained.

The lyrics to an old song began running through my head: “My love for you will not fade away.” Pop lyrics are a strange source of mystical inspiration, but as I heard these words, the material world around me disappeared, and in its place I felt a powerful and enduring love, both for and from the builders of the monument, and all the other humans who had ever been there. I saw Stonehenge as a unifying symbol of awe for God and for human endeavor, throughout time. Though in America thousands of people had died, and hundreds of thousands around the world were grieving those deaths, I felt comforted and reassured that this love was stronger and more lasting than the suffering.

A helicopter appeared overhead, circled around, and hovered, thrumming loudly. Large and dark gray against the gray sky, it made contemplation impossible.

“How revolting!” I shouted to Nic over the noise of the engine.

Nic agreed, yelling sarcastically, “What a great idea! Let’s rent a helicopter to see Stonehenge!”

It should be silent on those plains, or there should be only the sound of wind and rain and dead Druids. I hoped the helicopter would leave once the tourists inside had taken their snapshots, but it stayed. The mood was further degraded by a PA announcement asking if someone had lost a backpack. I wanted everyone just to be quiet, so I could go back to my reverie, but then a second helicopter flew over, this one smaller, painted red and white. Probably rich Germans or Americans videotaping the still and silent stones.

A whistle sounded. From the corner of my eye, I noticed a guide blowing a whistle and waving her arms at some visitors. Another guide, frantically gesturing, began shooing the tourists back toward the parking lot. I thought of the scared Hispanic cop on CNN shouting, “Go north! Go north!” after the first building fell, as the ghost-gray people trudged by him.

“Nic,” I said, “this is a bomb scare! That backpack they were asking about — they must think it has a bomb.” Nic looked up from her drawing. Some visitors were running, frightened.

I urged Nic along even before she could put away her pad and pencil. As we moved toward the exit, I saw a big blue backpack by the rope that separated the path from the grass. It looked abandoned, even vaguely ominous.

We were the last visitors to leave the area. Half a dozen police cars had parked on the curb, and an ambulance was pulling up. Buses poured out of the parking lot, the occupants looking back through the windows, their faces scared.

Then someone shouted that the backpack had been claimed; it was safe to go back. As it turned out, a young Asian photographer had left the backpack unattended — because he didn’t speak English, he hadn’t understood the announcements asking about the backpack’s owner.

So the bomb scare was relatively trivial and brief, but we couldn’t laugh it off. There could easily have been a bomb there, and whoever had left it would have been sure of killing a good number of Americans.

Soon, the helicopters had gone, and with most of the other tourists frightened back to their hotels, the peace of Stonehenge was no longer disturbed. But my peace was. Despite the great mystical presence I’d felt in this place, there was no safety here. And if we couldn’t be secure on a lonely plain at an ancient religious site, then it seemed there was no place safe on earth, for anyone.

On Thursday, September 20, I was at my friend Paula’s house watching Michael Radford’s film version of 1984, which I planned to use for a class I am teaching this fall. We were forty-five minutes into the film when we stopped the VCR in order to listen to the President’s speech.

So far, we’d learned that Winston Smith, the hero of 1984, works in Oceania’s Ministry of Truth, changing archival issues of the Times so as to coincide with the facts as Big Brother presents them. People who have since become “unpersons” are simply deleted, references to national production are altered to serve the party’s current pronouncements, and all military predictions are corrected so as to make it appear that the government never made a bad guess.

Oceania is a society in which all human effort is dedicated to the war against Eurasia. Winston and his countrymen live lives of deprivation amidst a landscape of smoldering rubble. At the point where we paused the film, Winston and a woman named Julia had committed themselves to renting a secret apartment where they will go to make love, the ultimate act of resistance.

We switched over to CBS and listened as the President spoke with drama and eloquence. He acknowledged the suffering of the Afghani people and made a number of positive references to Islam. He said the terrorists belonged to “a fringe movement that perverts the peaceful teachings of Islam.” He said that the teachings of the Muslim faith are “good and peaceful,” and that no one should be unfairly treated because of their ethnic background or religious faith.

Yet despite his words, his body language spoke another message: that unfortunate smirk made him appear to be enjoying his declaration of protracted and uncertain war.

Over dinner, Paula and I discussed the things the President had not said. He had not said anything about the fact that Osama bin Laden, and others who share his radical views, had been trained in CIA-financed camps during the period when the Soviets were our enemies and anyone willing to help drive them out of Afghanistan was our ally. He had not acknowledged our role in engendering the animosities that led up to the September 11 attack, most of all the bombings of Iraq, of terrorist training camps in Afghanistan, and of a Sudanese pharmaceutical company. And the President had never once mentioned oil.

Still more troubling, the President had not set any boundaries around this new war. “There are thousands of these terrorists in more than sixty countries,” he’d said. That sounded as though he were writing himself a blank check. Is Cuba one of those countries? Is Colombia? Is Ireland?

After dinner, we finished watching 1984. In one scene, the omnipresent television announces: “Oceania is at war with Eastasia. Oceania has always been at war with Eastasia. Eurasia is our ally. Eurasia has always been our ally.”

A few scenes later, Winston is called into the office of O’Brien, an Inner Party member, who tells him the enemy has “attacked an unarmed village with rocket bombs and murdered four thousand defenseless, innocent, and peaceful citizens of Oceania. This is no longer war: this is cold-blooded murder. . . . The endless catalog of bestial atrocities which will inevitably ensue from this appalling act must, can, and will be terminated. The forces of darkness and the treasonable maggots who collaborated with them must, can, and will be wiped from the face of the earth.”

I spent several days thinking about the parallels between 1984 and the President’s speech, and wondering whether my students would even be provoked by this film. As we narrow the distance between Big Brother’s institutionalized lies and the omissions of our own president, does 1984 even have the power to shock?

I’ve been seeing a psychiatrist for panic attacks — a vague fear that suddenly balloons into a full-blown terror of fainting, or vomiting, or even worse, going insane. My appointments are on Tuesdays at ten o’clock.

On the morning of Tuesday, September 11, I drove my daughters to school, said goodbye to my husband, who was working in Washington, D.C., that day, and chatted briefly with the men who were painting my house — their faces in every window, as if I were under observation. The house painters were listening to the radio. “Two planes have hit the World Trade Center,” one of them told me through a half-open window. They came down from their ladders and stepped inside to turn on cnn. I looked briefly at the news, saw the burning towers, and went to call my brother-in-law in Manhattan. “Go home,” I told him.

“I can’t,” he said. “We’re stuck. There’s no way out of the city.”

I hung up the phone and cried.

On the way to the psychiatrist’s office, I turned on the radio. Every station was broadcasting the fact that “something” — they weren’t sure what — had hit the Pentagon. I turned the radio off and called my husband on his cellphone; we could barely hear each other, but he managed to tell me that he was turning around and driving back to Baltimore.

By the time I walked into the psychiatrist’s office, I was eating a Balance bar to combat the nausea. I launched into an explanation, but my mouth was full, and he couldn’t understand me. I chewed, swallowed, and gave him what little information I had: two planes had hit the World Trade Center and something had hit the Pentagon.

“And how do you feel?” he asked.

There was a certain calmness and serenity in his demeanor: the direct stare, the notebook steady in hand, one leg casually slumping across the other. He hadn’t heard the news.

“You have to call your mother,” I said.

“Why?” he asked in his official doctor voice, the voice that says, You’re in a panic, and I am not.

“Your mother is in D.C.,” I said.

“The Pentagon is just outside D.C., in Virginia,” he said.

“But something hit it! You must call your mother.”

“Will it make you feel better if I call my mother?” he asked.

“Yes.”

He went to his desk and called his mother. An answering machine picked up. “It’s me,” he said tiredly, as if suppressing a yawn. “Something happened at the Pentagon, so traffic might be pretty bad out there. Perhaps you should turn on the radio before you go out.”

That night, as my husband and I watched TV, it occurred to me that my psychiatrist was watching, too. Would he recall his session with the panic-disorder patient who finally, truly, had something to panic about?

In the early-morning hours of September 11, I awakened in a cheap Las Vegas motel room to the news that the World Trade Center had been attacked by two hijacked commercial jetliners. I’m a poker player from the Boston area, and I had been running well for days. Eager tourists with fat wallets from cities like Tulsa, Harrisburg, and Dubuque had been clamoring for seats at the $8-$16 Texas Hold ’Em tables, eager for a chance to give their money away. Suddenly, everything was changed.

Even the better part of a continent away, there was no escaping the monumental human, economic, and symbolic dimensions of what occurred that Tuesday morning. As a steady stream of tourists found their way out of town, with no one coming in to replace them, Las Vegas was quickly being drained of its lifeblood. The strip appeared nearly deserted; hotels were laying off employees; taxicabs languished at curbside. A mere three or four days after the attack, the city seemed a fallen animal, her flesh twitching at the site of the blow.

I surprised myself by soon returning to the card tables. For one thing, except for watching television, there was nothing else to do. Also, it seemed better to be with people. A patriotic spirit the likes of which I had not seen in my lifetime was spreading over the land. Many hotel and casino signs, previously devoted to showgirls, magicians, and slot-machine payouts, were now given over to images of shimmering flags and messages of “God Bless America.” Cocktail waitresses in skimpy outfits passed out miniature American flags to anyone who wanted one.

As the days went by and the stock markets prepared to open, pundits of various stripes appeared on television and urged the public to buy stocks as an expression of their belief in America — as if belief alone were enough to save the market. Soon, of course, the stock market was in the midst of one of its worst declines in history.

At the poker table, I began to think a great deal about this matter of belief. The world, it seems, is lousy with it. Poker players — the bad ones — believe in luck. Jerry Falwell believes, or at least said he believes, that the attack on America was a punishment from God. Some well-educated Middle-Easterners, I have heard, believe the attack was orchestrated by Israel, and that precisely four thousand Jews received an early morning wake-up call on the morning of September 11 warning them not to go to work. Meanwhile, Americans cling to the belief that wealth has the power to keep us safe.

Sitting in Starbucks, I’m struck by how everything around me has been arranged for my comfort. My hot chocolate is delicious, topped with lots of whipped cream. Right outside the door is another favorite addiction, a discount clothing store, where, for twelve easily earned dollars, I can buy some cheap, bright sweater made by someone in a Third World country, working for pennies an hour. No matter; new clothes make me feel sexy and fabulous. And don’t I deserve some comfort here? After all, my country has been attacked.

The streets are dripping with American flags: big flags, little flags, waitresses wearing flag pins and ribbons. The American flag is the latest trendy logo.

I have just spent a week torturing a poem about the World Trade Center’s destruction, and my poetry-goddess friend Ruth maintains that it still doesn’t work. “It’s not cooked yet,” she insists. Damn! Well, of course it’s not cooked; it’s only been ten days since the world split open.

Pablo Neruda wrote:

If we were not so single-minded about keeping our lives moving, and for once could do nothing, perhaps a huge silence might interrupt this sadness of never understanding ourselves and of threatening ourselves with death.

A huge silence. If I were truly sincere in my desire to bring peace, I would just shut up and give blood. Then again, I’m human; I need to talk.

To the American people, I have this to say: I love you. I love us. I can’t help it; I do, even though I know how spoiled, selfish, and ignorant we are, how much of the world’s resources we guzzle, how deliberately blinkered our President and most of our politicians are.

The media pundits talk about our “loss of innocence,” as if we were innocent; poor us, we didn’t realize we’ve been bombing and starving innocent civilians in Iraq for the past ten years — the networks didn’t tell us. We didn’t realize what was going on with the Palestinians, or how we abandoned the Afghanis and the Pakistanis after the Cold War was over; that was so complicated, and the names of the countries around there are impossible to pronounce.

But I love us anyway, even sitting in this corporate, cushy, silly Starbucks. I love the mix of cultures and races and languages that flow through here without a second glance. I love our brashness, exuberance and style, even as I wince to think how it offends people who come to life with a humbler, more community-centered attitude. I have learned a lot from foreign friends about how to be gracious and think of others. But they have also told me how much they appreciate our openness, how Americans speak their minds and engage with new ideas.

And I love this ground I walk on, even knowing how much innocent blood was shed in its conquest: the rich black earth of Boston, with its melancholy tang in autumn, its never-ending winters and heavy summers; and California, where I live now, which smells of eucalyptus, bay laurel, jasmine, and sage. I’m glad my ancestors left Russia and Poland and Hungary to come here a hundred years ago. Very, very glad. Think what my life would have been like otherwise. So when my friends on the left try to totally disassociate from our culture, I want to say, Please. We have to work with what we’ve got.

It’s hard to realize my appropriate place among the creatures and beings of this earth in a culture where everything is designed for my seduction and comfort; where everything I touch is corporate-sponsored and made in a sweatshop; where the food I eat is grown by agribusinesses; where the car I drive poisons the atmosphere. To know all these things and continue consuming anyway creates a cognitive dissonance so severe as to be almost unbearable. But we have to bear it, look at it, own it if we are to begin the arduous process of actually changing things.

At a conference, I heard a writer speak of how she came to quit her corporate job and write full-time. She said she practiced stepping out of her comfort zone a little bit at a time. She left her soft bed before she wanted to, turned off the hot water in the shower before she was finished, allowed herself to feel progressively larger discomforts. In this way, she came to trust in her own ability to face adversity. Then she quit her job, went freelance, and threw up every day for a month out of sheer terror.

As a culture, we need to progressively move out of our selfishness zone. Start with the smallest things: yielding the right of way, listening instead of speaking. Then move on to bigger challenges: becoming scrupulous consumers, becoming involved citizens who can speak with integrity, giving back to life more than we think we can afford.

In the elevator Tuesday morning, going up to work, after the planes had hit but before the towers fell, I stood with two white men, an East Indian woman, and a Latino delivery man. One of the white men said abruptly to the Latino man, “Where are you from?”

“Sergio’s,” the man said, naming the restaurant where he worked. The white man seemed unsatisfied. What is this guy getting at? “Mexico?” the deliveryman said, trying again.

The white man shook his head. “We should just flatten the whole Middle East, turn it all into a big parking lot. China, too. All those places.”

I exchanged glances with the East Indian woman, who works on my floor. Then I said, “I think it’s a little more complicated than that.”

As the elevator doors opened, the other white man muttered, “Just a little.”

On the train that Friday morning, there was complete silence except for two West Indian women talking loudly to each other in Patois. When they finished their conversation, one of the women began to sing along with the music she heard in her headphones: “I want to be like Jesus, I want to be like Jesus.”

Directly across from me sat a fragile-looking, older Jewish man wearing a black suit and a yarmulke. He looked exhausted and ill, very pale, with three small sores on his face. He was praying silently, mouthing the words. He would pray himself to sleep, then jerk suddenly awake and resume his prayers. He took out a small white prayer book wrapped in a plastic baggie; it was falling apart, the pages stained and the cover partially burned. He unwrapped it carefully, read a bit, then put it away and continued to pray.