When Li-Young Lee talks about God, his eyes light up, and he leans forward, hands on his knees, every bit the image of a young boy eager to tell you about some great discovery. In his poetry, too, he tackles fundamental themes — the presence (or absence) of God, the nature of identity, the meaning of beauty — with a childlike wonder that, though it may seem naive at first, is profound in its piercing clarity.

One of the youngest poets ever to be included in the Norton Anthology of Poetry, Lee was born in Jakarta, Indonesia, to Chinese parents, in 1957. His mother is a descendant of China’s first president, and his father was a personal physician to Mao Tse-tung. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Lee’s parents fled to Indonesia, where his father eventually became medical advisor to President Sukarno. In 1959 Sukarno began a campaign to purge Indonesia of Chinese and Western influences, and Lee’s father, who loved Western culture, from the Bible to Shakespeare, was imprisoned for nineteen months. At the end of his incarceration, the family left Indonesia and spent time in Macao, Japan, and Hong Kong before settling in the United States in 1964. Lee’s father became a Presbyterian minister, and Lee spent the rest of his childhood in a small Pennsylvania town. Ashamed of his inability to speak English, he rarely spoke and played only with other foreign-born children.

Lee now lives in a Chicago row house with his wife and their two sons, his mother, and his brother and sister-in-law, each branch of the family occupying a different floor. Although Lee considers himself an American poet and was raised as a Christian, his work is informed by a broad understanding of various spiritual traditions, particularly Taoism and Buddhism. Clearly the poetic tradition of China has left its mark on Lee. Though he has never lived in the country of his ancestors, he remembers dinners at which his parents and their Chinese guests would compete to see who could recite, from memory, the longest and most complex poems in Chinese.

Today Lee is in constant demand for readings and talks on college campuses across the country, but he spends his summers loading boxes in a book warehouse. He is the author of Rose (BOA Editions), which won the Delmore Schwartz Memorial Poetry Award, and The City in Which I Love You (BOA Editions), a Lamont Poetry Selection. An insomniac, Lee often writes at night, and his most recent book of poems is titled Book of My Nights (BOA Editions). His memoir The Winged Seed (Simon and Schuster) received an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation.

When we interviewed Lee, he was in New Hampshire for two weeks, teaching in the MFA poetry program at New England College. The three of us huddled together in a small dormitory meeting room that turned out to be a well-used thoroughfare. The interview was interrupted repeatedly as Lee introduced us to other faculty members passing through, including his mentor Gerald Stern. Though brilliant and reflective, Lee was also playful and unpretentious. (He prefers B-grade kung fu movies to art-house cinema.) He stopped the conversation more than once to ask, “What are we talking about? Does this make any sense?” As he often does in his poems, he answered questions with other questions, probing for what cannot quite be said in words.

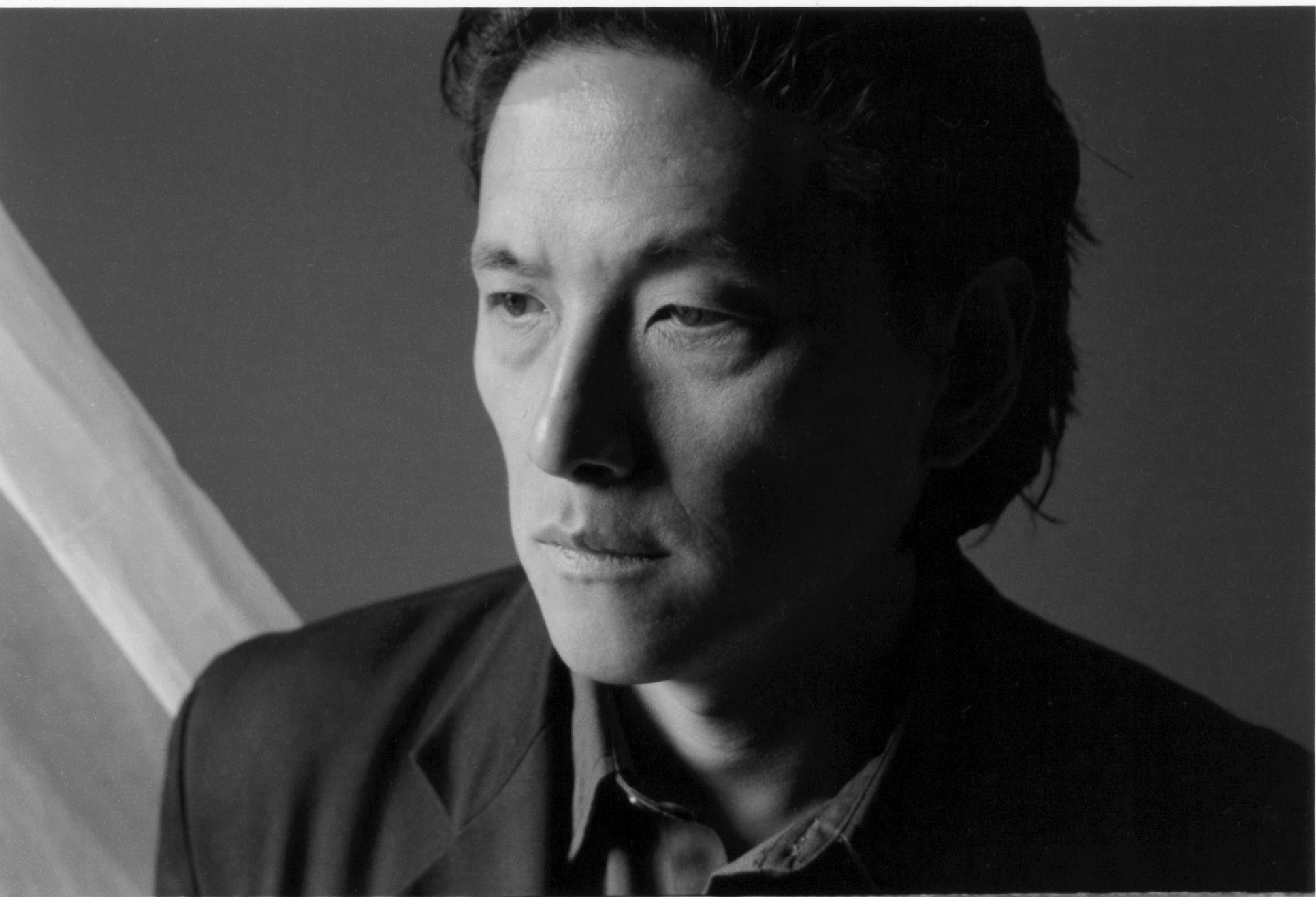

LI-YOUNG LEE

© Donna Lee

Kaminsky and Towler: English is not your first language, though it is the language in which you write. Do you see yourself as a poet who writes in a foreign language?

Lee: It happens that, as time goes by and I use English more, it grows less alien to me. But I feel the real medium for poets is silence, so I could be writing in any language. To inflect the inner silence, to give it body: that’s all we’re doing. We use the voice to make the silence more present. It’s like in architecture, where the medium is not really stone or metal, but the space they enclose. We use materials — brick, glass, words — to inflect space, both outer and inner. So I would say the real medium of poetry is inner space, the silence of our deepest interior.

Kaminsky and Towler: The theme of exile comes up repeatedly in your poems. Is the United States a place of exile for you?

Lee: I’ve taken that personal, historical — what I’d call a “horizontal” — phenomenon of exile, and I’ve seen it as a metaphysical phenomenon. I feel as if I’ve been exiled from a state of identity. When I was little, there was a shared identity between the world and me: I was the world; the world was me. There was no difference. Then suddenly I began to feel apart from that, and since then, I’ve been trying to get back to that sense of shared identity. So I guess you would say I’ve been exiled from Eden, from the Garden.

Kaminsky and Towler: But does this feeling you describe derive from an actual exile from a country — China or Indonesia — or is it just your state as a human being?

Lee: I feel as if what I have gone through on the horizontal plane of history coincides with what we all go through in our psychic lives. I see that parallel between personal history and psychic history in my life as lucky: it makes things clearer for me.

But I would like to be known as a poet of reconciliation, a poet who made it back from exile. You see, I have children, so everything’s at stake. My final report to them can’t be that our true human condition is homelessness and exile. Of course, if that’s what I ultimately discover, then that’s what I’ll report. But my hope is that someday I will be a poet of blessing and praise. I need to find my way home, and I need to get there authentically.

William Butler Yeats said that we make the self in the poem. Whatever you profess, whatever you write in a poem, is a self that you are making, and this is the self that you pass on to your children. My children don’t take from me what I say, but rather who I am, and who I am is in large part the self that I uncover in my poems, whether that be a homeless wanderer or a man rooted in a deeper repose.

Formal religion takes calcified poetic images and worships them for two thousand years. But the poet makes fresh religious images. . . . Poetry provides a very deep, immediate service, like a vital church service. It is proof that contact with God is possible without a middleman.

Kaminsky and Towler: You spent the early years of your childhood moving from country to country with your family. How much of that unsettled time has stayed with you?

Lee: I have body memories, visceral feelings from that time. The other day I opened the back-porch door and got a blast of winter air: suddenly I was reliving our first winter in America, its newness and strangeness. I also have vivid visual memories, but they lack context; they’re just images, little explosions without surrounding narrative. Maybe that’s just the way my mind works. Or maybe it’s because, at the time, my parents were inundating me with narratives of their own, so I couldn’t make any up myself.

Kaminsky and Towler: What were their narratives?

Lee: My father was very involved with the books of the Old Testament, studying and translating them, so many of the narratives he gave us were his interpretations of those biblical stories. Looking back now, I guess those narratives were his version of the Midrash, the biblical commentaries of Judaism. The way he told those stories led us to believe that we were the exiled children of Israel, and Sukarno was Pharaoh. He saw our plight as a version of surviving the biblical flood. The family was our ark. With the stories, songs, and photo albums, we would start over again once we had found shore.

On the other hand, my mother, who came from the ruling family that had been displaced when the Communists had taken over China, was filling us with stories from her childhood — tales of haunted mansions, heroic uncles, ignoble ancestors, concubines, and so on. On the whole, my parents’ stories probably helped us. They gave a kind of mythic context to our experience, saving it from being merely late-twentieth-century political exile.

My earliest complete memory from Indonesia is of a servant bringing in a basketful of eels, pouring them out into the yard, and then chasing them around and chopping their heads off, because we were going to eat them that night. For a child that sight — the eels being beheaded — was both violent and sexual.

After our move to the United States, I remember the little house where we lived in Seattle, with a hill and woods in the back. I remember that it was a sad time for us, and my mother cried a lot. One of my father’s first jobs in this country was as the token “Chinese man” in the China exhibit at the World’s Fair. He was unhappy about that.

Kaminsky and Towler: After you’d moved from Seattle to Pennsylvania, your father enrolled in seminary and became a Presbyterian minister. Why did he go into the ministry?

Lee: It started when my father was imprisoned in Indonesia. Sukarno said that he and the CIA had been planning bomb attacks — a ridiculous, made-up charge. Sukarno was just locking up Chinese; it was Sinophobia. While in jail, my father had a conversion experience; as he put it, he “died.” His cellmate washed his body, and the state put him in a new suit and pronounced him dead. They were going to bury him, but he “came back to life,” or perhaps he was never really dead. I don’t know. My father said when he died, he “saw things.” He said God gave him back his life, so he decided to give his life to the ministry. He began preaching while still in jail.

All my father’s life, I think, he was wrestling with visions of God that he found contradictory. On the one hand, there was a God who acted in history; on the other, there was a God who was a condition of the pure present. I think this is what I wrestle with, too. But I’m beginning to believe that the two visions aren’t mutually exclusive; that they might be seen, rather, as a fruitful paradox. The whole idea of a historical God fascinated my father when he converted. He started to feel that he had a destiny.

Kaminsky and Towler: How do you see the historical God?

Lee: I believe that God unfolds a divine will in history. By “history,” I mean human phenomena. We can read history as either the story of humans or the story of humans and God. For me, if history is read just as human endeavors, it’s not interesting. I think a deep orderedness permeates all phenomena; call that orderedness “God,” or “Tao,” or “the vast hand of Buddha” — whatever your Jewish mother or Buddhist father called it. I believe poetry is grounded in this order.

But here’s something I’ve been troubled by lately: I think there is only one subject. It makes me nervous to say it, but this subject is the “I.” Now, either the “I” is very deep and embedded in a bigger “I,” or it’s just this tiny little “I,” floating around like a piece of confetti. I’m not referring to the ego, nor do I mean to imply that we humans are the only thing. But every time we experience a poem or a piece of art, the real subject is the “I.” What art can do is give us a version of the “I” that is manifold and deep, that has both divine and human content. When I say “divine and human,” it sounds as if they were separate, but they’re not. It would be more correct to say “divine in human.”

Kaminsky and Towler: The best poems are better than the poets who wrote them.

Lee: Yes. I think that poetry is the most a human being can be. What we actually get when we read a poem is presence; that is the ultimate subject. I do think that there are poems where the presence is more complete, and other poems where the presence is less complete. What troubles me are the ethical implications of projecting into the world an “I” that is less than the best of who I am, a presence that might even be toxic in one way or another.

Kaminsky and Towler: With a father who was a minister, you grew up in church. Are there memories of that time that remain important to you?

Lee: It was a rich life, pregnant with symbols: the loaves and fishes, the Bible stories, Communion, all of it. The church itself was a huge symbol, especially when it was empty. I loved sitting in the church by myself. I don’t attend church now, however, because it’s not pregnant for me anymore. Poetry is. I believe that poetry is natural religion. (I’m not the first person to say this.) Formal religion takes calcified poetic images and worships them for two thousand years. But the poet makes fresh religious images for him- or herself. Poetry provides a very deep, immediate service, like a vital church service. It is proof that contact with God is possible without a middleman. Read Emily Dickinson: through all her quarrels, she affirms this.

Kaminsky and Towler: In The Winged Seed, you write about bringing Communion to the disabled and the poor with your father. How did your experience of being a poor immigrant, and then watching your father minister to the poor, affect you?

Lee: I don’t know what to say about poverty. We were poor. At one point, my mother sold her wedding ring so we could get by. But my father’s work brought him in touch with people who had even less. He saw astonishing suffering, destitution rivaling the worst slums of Jakarta or Hong Kong, except this was in rural Pennsylvania. In the area where we lived, the people earned their living mainly as coal miners and steelworkers, but most of the mines had closed down, and the mills were beginning to fold, so plenty of people were out of work. There was a lot of alcoholism. And there were those who didn’t even have money for alcohol. I was dumbfounded to find people in the twentieth century in the U.S. living in the hills in unheated shacks. I remember thinking, That guy lives in a shack and survives on squirrels and dandelion leaves. What the hell is this? Aren’t we in America? Traveling with my father to visit shut-ins, I saw shocking things, inhuman conditions.

But I believe the experience was good for me. When my wife and I moved to Chicago with my mother and my siblings after my father’s death, we bought an old house that was falling down. It was a former crack house, but it was the only place my family could afford. The sheriff came and threw out the crack dealers and prostitutes, and we moved in. Everybody but me wanted to rehab the house. I kept saying no. When they asked me why, I said it was because if Father came back he wouldn’t recognize it, because he’d been so poor. I thought we had to live poor for his sake. Now, however, knowing a little of my own psychology, I realize I must have meant the father in me. I didn’t want to live in a nice place; I wanted to live in a poor place.

We still live in the same house. Little by little, we’ve been working on it, and it’s been very painful for me. All my siblings, my wife, and my mother have been saying to me, “It’s OK, Li-Young. We can afford to have a new door. We don’t have to have an old door that is falling off its hinges.” It’s not that I want to romanticize poverty. It’s that I feel that’s where I belong — that poverty is in some sense essential.

Kaminsky and Towler: Is poverty essential in terms of the lessons you learn from it?

Lee: Yes. I think it shapes the hierarchy of your values. If you’re poor, you realize that you wear terrible clothes that you got from the neighbor, and that when you’re done with them, you’re going to give them to your brother, and so on. On Christmas we had no real presents to give, so we gave one another presents from our own belongings. When you live like this, you ask, “What is my value in the world?” You know you can’t answer, “I’m rich,” or even, “I’m clean.” So you begin to value people differently. Does this mean that everybody should be poor? I would say that I was fortunate to experience poverty and fortunate to get out of it.

Kaminsky and Towler: You’ve had a varied work life, including running a restaurant with your brothers and working in a warehouse. How have these different kinds of work affected you as a writer?

Lee: When my brothers and I owned a restaurant, it was magical. I enjoyed cooking with my brothers. I loved the people I met, and we even won an award for “Best Chicken Wings” at the Reading Terminal Market in Philadelphia. But it was hard work, too hard. I think physical labor is ennobling for about three minutes, and then it’s just drudgery.

I work in a book warehouse now, in the summer, moving boxes of nursing textbooks, coffee-table books. Last summer my sons worked with me there for the first time. The first week, my oldest son said, “Hey, Babba, I can just work here the rest of my life and read books.” I told him to tell me how he felt after the third week. About the third week, he said, “I don’t know how you do this. It’s just eight hours of the same thing. It’s boring, endless.” There’s no shape to that kind of work, no beginning or end. It’s drudgery, heavy and dark. So, by the third week, my son said he didn’t want to work there anymore, and that he was going to college.

I keep working there for the security: I know, when things get tough, I’ll still have a job. But it doesn’t leave my mind free for other things. Mind is body, and body is mind, right? So if your body gets drained, your mind gets drained. If I could do whatever I wanted to do, I’d read books, take walks with my wife and my kids, and write poems. Basically, I’m pretty lazy.

Somebody asked Gerald Stern after 9/11 if he could write a poem for the occasion. He responded: “I already did. It’s all I have been doing.” In a way, every poem is written at Ground Zero.

Kaminsky and Towler: Many of your poems seem to be addressed to an unseen God who is nonetheless tangibly present, a physical force. How does your dialogue with this presence inform what you write?

Lee: I feel that the poems are addressed to an “all”: the stars, the trees, the birds — everything. When I’m writing a poem, I feel as if the whole future of the universe depended on that poem. Of course, I laugh as I say this, but I do feel this way. Somebody asked Gerald Stern after 9/11 if he could write a poem for the occasion. He responded: “I already did. It’s all I have been doing.” In a way, every poem is written at Ground Zero. Yehuda Amichai said, “Every poem I write takes all of human history into consideration, all the atrocities, all the good stuff, and it’s the last poem I’m going to write.” So there you are, writing at Ground Zero all the time. The audience is everything: birds, trees, stars, women, children, men, grandmothers, aunts, uncles. Everybody is listening.

Kaminsky and Towler: Although God is a constant presence in your poems, you do not invoke God in purely Christian terms. How do you define your belief, if at all?

Lee: Taoism speaks of “the way,” which is, ultimately, the will of God. If you feel that will working every day in your life, then everything will be all right, because you will abide by that will.

I feel that God is a mystery, but it’s the only subject for me, because I sense that God is our deepest identity. If a work of art lacks the presence of God, then it’s not even art to me. For me, the definition of poetry is very narrow, but then, my definition of God is very wide. So, for instance, I would say that God is all through the poetry of Robert Frost, even though he was an atheist. In Frost’s work, the surface subject is people, but there is a deeper divinity in his lines, a will that is beyond Frost’s personal will.

The “problem of problems,” as Sigmund Freud put it, is the ethical problem: right and wrong, good and bad. If a poet doesn’t tackle this problem, doesn’t face it down and come to a conclusion, then he or she is just making knickknacks, just decorating. I believe the only possible ethical consciousness is one that accounts for the whole human being, that doesn’t leave any of it out — and this is precisely what poetry can achieve. On a social scale, this would be a government that accounts for all of its population — the poor, the rich, women, men, children, old people, black, white. Poetry is a way to integrate all of who we are: the saint, the murderer, all of it. By this, I don’t mean to suggest that we give the murderer free rein, but we have to account for that aspect of human psychology and understand it, not just push it aside.

Kaminsky and Towler: Jewish theologian Martin Buber spoke of this question of ethics in his book I and Thou. Is he an important writer and thinker for you?

Lee: I would want to move past “I and thou” to “I and I.” What if we could walk through the world and practice “I and I”? Christ said this, right? Treat your neighbor as yourself. If we looked at everything in the world as ourself, then that would be complete enlightenment. We could never hurt another person after that. But we’re so unenlightened, we haven’t even gotten to the point of simply loving ourselves. There are plenty of people cutting themselves, killing themselves, drinking themselves to death. I believe the practice of poetry can help us move toward loving all of who we are. It can help us become more comfortable with things in ourselves that we don’t like.

Kaminsky and Towler: What you’re saying might be true for the person who writes poems, but what about people who only read poetry?

Lee: That would be like only having heard about the burning bush. You’ve got to write poetry. If you just read it, then you can only hear about the burning bush, but if you write it, then you sit inside the burning bush. I have friends who say, “The only people who read poetry are people who write it.” I think, Well, of course. And everybody should be writing it.