I first encountered the work of Jacob Needleman about thirty-five years ago when I read his 1970 book The New Religions, which reviewed the eclectic spiritual landscape that was then just beginning to flower in the West. I had studied a little philosophy in college, but the academic perspective seemed intellectually cold and remote, certainly impossible to apply to the challenges of everyday living. By contrast, Needleman has built his unique writing career as a popular yet erudite philosopher primarily concerned with the great questions: Who are we? What’s going on here? And what is our real purpose in life? The range of his concerns is reflected in the titles of his books since the 1970s, including Lost Christianity, The Way of the Physician, The Heart of Philosophy, Money and the Meaning of Life, The American Soul, Why Can’t We Be Good?, and, most recently, What Is God?

As a journalist I’m indebted to Needleman for a concept he pioneered: “the warmth of real objectivity.” Western science and rationalism have schooled us in the idea that objectivity consists of being dispassionate, if not outright wary and cynical. Needleman suggests instead that real objectivity is suffused with a profound compassion. He writes in What Is God? that leaving the bias of the limited ego-self behind opens us up to the living experience of God — not God as a judgmental deity watching us from a throne in the sky, but God as us:

It is only in and through people, inwardly developed men and women, that God can exist and act in the world of man on earth. Bluntly speaking, the proof for the existence of God is the existence of people who are inhabited by and who manifest God. . . . God needs not just man, but awakened man, in order to act as God in the human world. Without this conscious energy on the earth it may not be possible for divine justice, mercy, or compassion to enter the lives of human beings.

Born in Philadelphia in 1934 and raised by Jewish parents for whom “becoming a doctor was the only human thing to do,” Needleman entered Harvard University with the intention of going on to medical school. But the young student’s obsessions with the big questions of life steered him into the pursuit of philosophy. “My father never understood what I was doing,” Needleman recalls, and his mother didn’t take his decision well either. When he received his PhD from Yale and was first introduced socially as “Dr. Needleman” in her presence, she interrupted to point out, “He’s not the kind of doctor that does anybody any good, you know.”

Needleman has never been the kind of philosopher that an academic is supposed to be, either. Early on he departed from the dry-bones pursuit of argumentative logic and analysis to deal with questions that inexorably cross over into the academically suspect realm of spirituality. At Harvard he was the only student to sign up for an esoteric course on the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy, and in ensuing years he studied Zen Buddhism and the other Eastern traditions. He also encountered the teachings of the Russian mystic G.I. Gurdjieff, which remain a touchstone of his perspective.

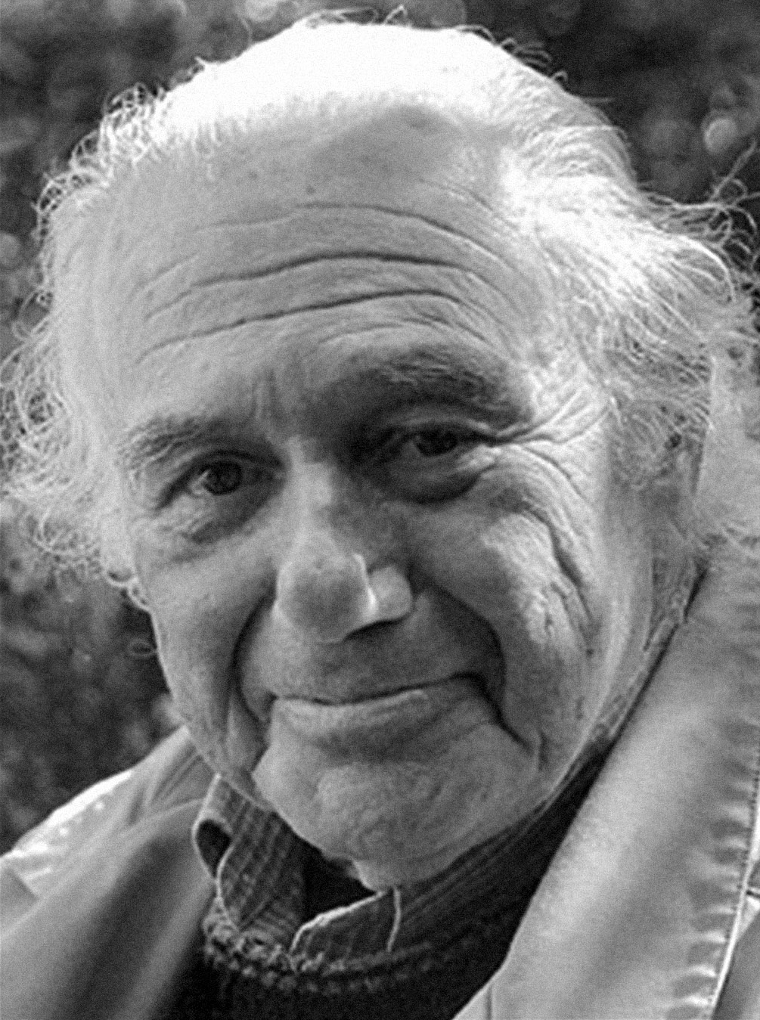

Needleman has spent more than five decades as a professor at San Francisco State University. The following conversation, focusing on What Is God?, is the fourth time I’ve interviewed Needleman and the third time I’ve interviewed him for The Sun. In an age when the search for spiritual meaning often seems reduced to one pop trend after another, Needleman delivers a wealth of insights with no pedantry or hyperbole. His remarks are always free of sound bites, and he takes the time to answer inquiries with thoughtfulness and an obvious concern for getting closer to the truth. It’s not unusual for a full minute of silence to pass between asking a question and hearing his response. I always get the feeling that he’s referring all inquiries to a higher authority — an authority that animates his face and his voice not with self-righteousness but with an openhearted curiosity that celebrates deeply shared questions rather than final answers.

JACOB NEEDLEMAN

Miller: What was your first recognition of God?

Needleman: I was eight years old, and it was summer in Philadelphia, a very hot and muggy evening. My father was sitting out on the steps, looking up at the sky, which he often did. He was a quiet man, though sometimes explosive, and I was in awe, and a little frightened of him. Even his silences were strong. We were overlooking the front yard, where he had planted a victory garden during World War II. There was a big area of weeds around it, which I just loved. It was heaven to me, walking through all that nature. We were on a low-rent street in an otherwise fine area of Philadelphia, close to the Wissahickon Creek, where some of the greatest mystical sects from Germany had settled and established communities. I didn’t know this at the time. I was just sitting there, looking up at the sky, and I was stunned by what I saw. Suddenly there seemed to be a million stars, far more than normal. The whole sky was filled, almost as if you couldn’t see between them. And at that point, when I was trying to figure out what was happening, my father simply said, “That’s God.”

Nothing else passed between us, and I wondered how he knew that I was trying to understand what I was seeing.

Moments like that, and other moments I had as a child in nature, were all I needed to know of God. I was not at all interested in Judaism, the religion of my ancestors. My parents were not religious, but my grandparents were Orthodox and often took me to synagogue. Yet I was completely allergic to that religion and their God; my God was in the trees and the sky.

Miller: Did your awe of your father heighten that moment when you were looking up at the sky together?

Needleman: Oh, no question. He was like God to me in many ways. He was not a highly developed spiritual man, but he did have a yearning that I would call deeply spiritual. He had the soul of a poet; he just couldn’t express it very well.

Miller: How has your experience of God changed through the years?

Needleman: All through my life I’ve experienced a sense of wonder that has to do with something that’s out there but also touches a place within me. It feels as if I’m part of something bigger. Once, when I was in Greece, I went into an Orthodox church and saw an image of Christ up on the ceiling — a giant head of Christ the Creator looking down on me. I felt the same sense that somehow reality or the universe was offering me a gift, but I wasn’t sure how to respond to it.

In the midst of such wonder, all my ordinary concerns, fears, and worries are quieted. The source or trigger for this wonder is always outside: the stars, the face of Christ, the extraordinary beauty of nature, looking at a slide of blood cells. But the experience is inside. What I see out there awakens an impersonal joy within me, as if this wonder is what I really am, rather than being my day-to-day self, which we can call the “ego.” In those moments the ego realizes that everything it always wanted — safety, security, happiness, the ability to give and receive love — is granted by this great thing outside me. Yet it is given to me within. And in that moment the ego submits, because it realizes that this great gift is not of its own making. This gift comes from God, and anyone can have it, without religious trappings.

For a while I led a double life in regard to God. On the one hand, I was a scholar and philosopher, respectful of religion yet fundamentally disbelieving of God. On the other, I had these transcendent experiences in which the word God was not even involved. I would have described them simply as encounters with “higher consciousness.” At some point these two ways of being merged; it was as if the wall between them became a porous membrane. I didn’t become a “believer” in the usual sense, but I recognized that my experiences of wonder were pointing me toward what God is.

Miller: You had an early encounter with the Zen master D.T. Suzuki.

Needleman: As a young person I went to Harvard intending to become a scientist. I considered myself an atheist and existentialist, but I didn’t buy the reductive scientism of the analytic philosophers, who were the leading thinkers of the time — at least, at Harvard. I had a humanistic bent that led me to pursue the great questions of meaning — what are good and evil, life and death? — instead of reducing everything to word problems and logical puzzles. I became a philosophy major and decided that would be my career.

I became preoccupied with the problem of the self: what is it? I was touched by the work of Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, who was an extraordinarily gifted and sensitive writer, but I tried hard to ignore the Christianity in him. A lot of existentialists did that, taking his deep psychological insights and downplaying the religion — which means they hadn’t really understood him at all. His questioning of the self had a great influence on my undergraduate work. I was fascinated with the problem of the self — understanding its true nature and its relation to the physical body and the world at large. In my senior year I became interested in Zen Buddhism through a series of essays by D.T. Suzuki, a great scholar and practicing master of the tradition. He was the one most responsible for bringing Zen to the West.

But Zen at that time was deeply incomprehensible. These days in many places it’s become so watered down that it’s hardly Zen at all. It’s become a brand, like Satori perfume. People make jokes about koans. It’s sometimes hard to recognize the original tradition anymore. When I first encountered Zen, its incomprehensibility also made it irresistibly attractive. What was this thing that could be so irrational and yet so deep and powerful, so alive with meaning?

In 1957 I heard that Suzuki happened to be visiting New York City, and I was eager to meet him. So it was arranged, and I went to a beautiful apartment where he was staying on the Upper West Side. There was this little man with these incredible eyebrows, like bat wings. And he had such a presence, a real strength of being. He was there in a way I had never experienced. I’m not talking about stage presence or charisma. He had a kind of stillness and quiet attentiveness that energized the atmosphere. When someone like that is in a room, your attention naturally goes to him or her. There’s an attraction that’s not sexual, not egoistic, not flamboyant. There’s something about the person that compels your attention and respect.

Miller: Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido, once said that the point of mastering that defensive martial art is to have the capacity to enter a room and quell any conflict without making a single move.

Needleman: Yes, that would be an expression of presence. It means someone emanates authority because of what he or she is, rather than what he or she does, says, or looks like.

I had prepared a question for Suzuki: What is the self? I’d written my undergraduate thesis on the question of the self and gotten a high grade on it, so I felt ready to pick apart his reply. I had Heidegger, Kant, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Hegel, and all these other philosophers on my side, backing me up.

Suzuki replied, “Who is asking the question?”

Now, in 1957, nobody talked that way. In fact, I was a little angry at his response. What did he mean, who was asking the question? All the philosophy in my head went right out the window, and I answered, “I am! I’m asking the question.”

He replied, “Show me this ‘I.’ ”

Now I was really annoyed. I couldn’t speak. I had no associations, no ideas, nothing to answer with. We were both silent for a while. Then we had some trivial conversation before I got up and left, deeply disappointed and puzzled — shaken, really, and thank God for that.

Had anyone else said, “Show me this ‘I,’ ” I would have thought they were being clever, trying to engage me in an intellectual game, but Suzuki’s presence carried such weight that I couldn’t think. I just couldn’t make any sense of it. I felt a great respect for the man in my gut, but my mind was confounded by him. That’s a very special state to be in. The part of me that could enter philosophical discussions and play the intellectual game was simply not admitted into the room. Here I was in the presence of this man whom I respected not because he was smart or widely published but simply for his being. And he respected me for my being, because that’s what he was calling forth with his challenges. He wasn’t interested in having an intellectual debate with me.

Miller: He was inducing in you the same experience that a Zen koan is meant to induce: stopping the mind.

Needleman: Yes, because to stop the mind within such a context is to touch someone’s being, to touch his or her yearning, the essential need in the person for a relationship to something higher.

Miller: So when Suzuki threw you back on the experience of your own being, you found yourself wordless.

Needleman: Yes. At the point of encountering your own being, you either have to remain silent or start singing. If you’re going to talk about “being” in any meaningful way, you may have to use special language, perhaps mythic language. Myth, in this context, is not falsehood. It’s the language of the heart and mind together, and it surpasses our ordinary way of expressing ourselves. Nature often speaks to us in mythic language. We tend to paper over nature with scientific language and think we’ve fully described it, but to look at nature only in that way is to muzzle it.

Suzuki was not going to give me an intellectual answer; he meant to put me in a questioning state so that I could experience something about the self — what it isn’t, what it could be, and so on. As Kierkegaard said, direct communication between people is not real communication. Real communication is indirect: it allows one to experience something rather than intellectually understand it.

Miller: It seems your father, by looking at the sky and saying, “That’s God,” was pointing you toward an experience rather than explaining what you were seeing.

Needleman: Yes, even if he didn’t know that’s what he was doing. It was an instinct he had. But with Suzuki it was his deliberate way of respecting another person’s spiritual search. He gave me an authentic answer, the importance of which I realized months later. I literally woke up in the middle of the night exclaiming, “So that’s what he meant!” It was my first experience of a real spiritual communication from a master.

Miller: There seem to be many such stories in spiritual literature, where the first thing a master has to say delivers some kind of shock to the student. Instead of having wisdom directly dispensed to you, you’re confronted with your own lack of resources.

Needleman: I can’t say for sure what Suzuki intended; it was a brief encounter, and I didn’t see him again. But the encounter certainly affected me as if he had meant to impart this lesson.

Other times the lesson comes from a source that doesn’t intend to give it. In the Hindu tradition there’s the idea of the upaguru, the “guru next to you.” This means that anything that is happening in your life at the moment can be your teacher, if you have the right attitude.

For instance, this drinking glass sitting here is not my upaguru at the moment. But if I were talking to you about how important it is to have awareness and in the process I absentmindedly waved my arms and knocked the glass over, then I might become aware of how unconsciously I was behaving while talking about being conscious. In that moment of heightened awareness, the water glass may become my upaguru, but only if I’m willing to pay attention instead of just saying, “Oops!”

That’s a lighthearted example, but there are countless more-serious instances in life where we have the opportunity to recognize and be conscious of what we’re doing and who we really are.

Miller: It reminds me of a Native American shamanic practice called “rock seeing,” in which you pick up a fist-sized rock and stare at it until you see a picture or just get a feeling from the stone that wasn’t there before. Psychologists would probably say that one is projecting the unconscious onto the rock, but I think the Native American perspective is that you’re actually becoming aware of what this bit of nature has to say to you.

Needleman: Yes, it’s the difference between projecting meaning onto a Rorschach blot, which is truly meaningless, and recognizing an inherent meaning in nature, which, from an indigenous perspective, is always speaking to us and yearning to be heard. The typical modern reaction to nature is instead to manipulate it or cover it over with our own artifacts. We’re constantly muting the living presence of nature in our lives.

But if you really give your full attention to nature, it does speak to you. If you’ve ever been out in the woods and suddenly experienced a shock of grief or awe or a sense of belonging to something greater, that’s because nature has spoken to you. That’s why there’s a timeless, universal tradition of experiencing God in nature. It’s one way of recognizing that we’re part of something greater than ourselves.

Miller: Not long after the encounter with Suzuki, you found yourself having to teach the fundamentals of Judaism and Christianity to college students while still considering yourself an atheist. What were your opinions of those two traditions at the time?

Needleman: Well, I thought of all religion as, at best, good literature: symbolic and interesting maybe, but to say that any of it was true — never! The most charitable view I could manage was the standard Freudian interpretation of religion as an illusion we project onto the universe because of our psychological weaknesses. I regarded Christianity as particularly perverse, especially the idea that it was meant to replace Judaism. I didn’t see Judaism as true either, but I still resented the implications. When I’d been a freshman at Harvard, I’d had to read The Confessions of St. Augustine, and I’d hated that book so much: all the thees and thous and sin, sin, sin. I just could not bear it. When the class was over, I went to the fireplace in my room and burned that book one page at a time!

Years later, when I started teaching at San Francisco State, I was required to teach the history of Western religious thought, and I had to read St. Augustine again to prepare for the class. This was after my meeting with Suzuki, and this time I found it to be a deeply beautiful book.

Miller: Perhaps any set of ideas toward which one has such a visceral negative response actually has an attraction that one doesn’t want to recognize.

Needleman: I don’t think so! [Laughs.] It’s more that my experience with Zen Buddhism had opened me up to a different way of accessing knowledge. I’d begun reading classic works in both Judaism and Christianity that I couldn’t stand before, and I could now see the wealth and depth of these traditions. Even though I was still an atheist, they had become deeply interesting.

Miller: How did the experience with Suzuki enable you to read St. Augustine differently?

Needleman: As I began my own search for deeper meaning, I recognized that, in terms of inner being or spiritual development, I was worse off than I’d thought I was. I was far from the state of being I wished to be in and had sometimes imagined that I was in. At the same time, I began to see greater possibilities for myself than I had previously imagined. Recognizing how many illusions I’d entertained about myself was not discouraging, because it was paired with the knowledge that I could be so much better. So the price of realizing our great potential is seeing ourselves as we actually are.

This idea is at the heart of Christianity, as well as every other great spiritual tradition. It’s what I think sin actually means, but I could not see that until after the experience with Suzuki had thrown me out of my mind, as it were, and into the experience of my own being. Before, I’d thought that Augustine’s references to sin meant that I was a bad person and should be punished for it. In my second reading I could understand that he was actually echoing the realization that I was not all that I could be. At that moment Augustine felt like my teacher rather than my judge.

Miller: The conventional idea of sin is that you’re not merely falling short of your potential; you’re no damn good and need to confess or testify in the hopes that God will forgive you. If that’s not what Augustine was saying, what was his solution to the problem?

Needleman: His solution was faith in God but, again, not in the way that we’re used to thinking of it. He meant the influence that one can feel from a higher level of reality. In this view God or Christ is a force or element of higher reality that has the quality of personhood. And only such a higher influence, however you experience it, can allow you to confront your fallibility. You can’t do it on your own at the level of personality. We can’t transform ourselves, but we can allow ourselves to be transformed.

To do spiritual work, you must invite into yourself a higher force or identity: God, Christ, the Holy Spirit, Higher Self, Brahma, Atman, Buddha-nature, whatever you want to call it. It’s a force that redefines the “you” who works on yourself.

Miller: So self-help is doomed?

Needleman: Self-help is fine for getting over some hang-ups, adapting to the world, and healing relationships to a limited extent. But self-help isn’t going to bring about the degree of transformation that a genuinely spiritual process does. Seeing yourself as you really are is a great healing force in itself, if you can bear it. Some people need therapists to help them bear it. But in self-help or therapy you’re chiefly working on the self you see. Spiritual change takes place when the seer, and not merely what is seen, begins to change and deepen. When the part of you that sees begins to deepen, then you’re opening to other levels of inner spiritual work. But to do spiritual work, you must invite into yourself a higher force or identity: God, Christ, the Holy Spirit, Higher Self, Brahma, Atman, Buddha-nature, whatever you want to call it. It’s a force that redefines the “you” who works on yourself. It’s an entirely different level of engagement.

Miller: How can we learn to see through religious language to the meaning it carries?

Needleman: One has to treat religious language as one would treat a person: you have to learn to listen to what someone is really saying. At first St. Augustine was so alien to me; the emphasis on sinfulness seemed so extreme that I couldn’t get past it. The word sin was a huge wall. To peek behind the wall of language does take some maturity or experience. Studying the mystic and spiritual teacher G.I. Gurdjieff helped me understand that sin is actually the idea that we are all deeply in need of help. Humanity’s situation is much worse than we like to think, and yet the possibility within humanity is also greater than we can imagine. I began to see that Augustine was speaking of this helplessness, this lack within ourselves, and the need to reach toward what we can be. That’s very different from the conventional moralism of sin.

Miller: When I interviewed the late John Sanford, a Jungian psychologist, he said that an encounter with one’s own dark side or “shadow” is always horrifying but also a necessary part of genuine growth. Is this similar to the recognition that humanity is in a far worse condition than we’d like to admit?

Needleman: Yes, the shadow is a big part of what we have to accept within ourselves. Everyone has an ego, and it’s a necessary part of our psyche. It helps us function in the world. But it’s not the whole story of ourselves. The ego is threatened by the shadow, which represents what we find undesirable in ourselves. But the ego can be taught to live with the shadow, which can heal you in some ways. Being at peace with your darker elements may free you from depression or suicidal thinking.

Therapy can strengthen and integrate the ego so that we can function in the everyday world and not fall apart, but there’s another element in oneself that has to do with divinity or the higher level of our psyche. It’s one thing to accept all the elements of our mind, from which our personality is derived; it’s another to accept our being. To put it in Christian terms, one of the great mysteries is the recognition that we are loved for what we are and also forgiven. At the ordinary level of the mind, this idea may seem sentimental, mawkish, or simply unrealistic. Properly seen, it’s a Christian koan that stops thought and forces us to face a big question: Why is it so difficult for us to accept total love and forgiveness? In the course of ordinary life we can find in ourselves a kind of acceptance of our flaws and peccadilloes, although that often involves some ignorance or denial of our bigger problems. But complete acceptance of the totality of our being is actually impossible at the level of our mind. It has to come from a higher level, from a consciousness that’s both within us and far beyond us at the same time.

Miller: Most academic philosophers steer clear of spirituality. What changed for you that made spiritual practice the focus of your work?

Needleman: One of the turning points of my life was reading Immanuel Kant’s The Critique of Pure Reason, a book with a reputation of being awesomely difficult, which it is. It’s like holding a cathedral in your hands. I was sitting on the steps of the Widener Library at Harvard when I cracked the book for the first time and encountered the opening sentence:

Human reason has this peculiar fate that in one species of its knowledge it is burdened by questions which, as prescribed by the very nature of reason itself, it is not able to ignore, but which, as transcending all its powers, it is also not able to answer.

That touched me deep down: the idea that the mind is incapable of answering some of the deepest questions it asks. It didn’t make me a believer in religion, but it made me realize that the situation I was in was profound. Although I didn’t know it at the time, I would later learn that this was the same truth expressed in Zen Buddhism and the Upanishads, and by the German theologian Meister Eckhart, Gurdjieff, and Krishnamurti: that the mind alone cannot answer the questions of the heart. For a long time I didn’t know what to do about this, but just grasping that concept was an important step in my turn toward the spiritual life, as opposed to conventional religion.

When I came to San Francisco, I became interested in the new religious movements that were taking root in the West. Some of them were dubious, and some of them were nuts, but some of them, like Zen, were very serious. Eventually I had a student who was interested in Gurdjieff and gave me a book called Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff, which I took home and read just to please the student. The book is by composer Thomas de Hartmann and his wife, Olga, who tell about journeying out of Russia during the revolution with Gurdjieff. I stayed up all night reading it, and toward the end I realized that I was in a rare state: the book had made me inwardly quiet in an unfamiliar way, and I wasn’t sure how it had produced that effect. The writing was nothing special. The story, though dramatic, wasn’t the source of the feeling. Somehow the book had just balanced me.

After that I reread In Search of the Miraculous, by Gurdjieff’s follower P.D. Ouspensky, which I’d first encountered when I was younger and hadn’t really understood. This time I was touched by it. To make a long story short, I decided to pursue the Gurdjieff teaching, and it’s stayed with me ever since.

Miller: What is Gurdjieff’s significance?

Needleman: He understood, as many great teachers have, that humanity is in a bad way. He called it “sleep.” He said that we live in illusion and have lost all contact with reality, both in the world and within ourselves. He did not use religious or metaphysical language; he used the words consciousness and being. He felt that most religion, as it was practiced institutionally around the world, often served only to deepen our sleep. It played upon our weaknesses and turned faith into a weakness of the mind, a form of sentimental wish fulfillment instead of a contact with deeper love, feeling, and trust.

Further, what we think of as free will is an illusion in Gurdjieff’s view. In fact, we are heavily influenced at every moment by forces within and without that we don’t see or understand. We think that we are freely choosing to do something, but instead we are actually driven to do it.

Gurdjieff used scientific and psychological language because he thought it would reach the modern, sleeping mind and give it a taste of higher awareness. He had rather harsh words about most philosophy, which he called “pouring from the empty into the void.” He had many ways of confronting people with their illusions about themselves. He said, “I wish to create around myself conditions in which a man would be continually reminded of the sense and aim of his existence, by an unavoidable friction between his conscience and the automatic manifestations of his nature.” He wanted to help people see that their automatic manifestations — what they say and do without awareness — actually contradict the innate demands of their conscience.

Miller: What is the central practice of his teaching?

Needleman: Conscious, willful attention to oneself and the world is the standard in the Gurdjieff teaching. When we say that we are “asleep,” we could equally well say that we have no conscious attention. Our attention is automatic, sometimes dispersed or distracted, and focused only when a temporary stimulus or urgent need magnetizes it. The Gurdjieff practice involves trying to open one’s inner life to another source of attention, starting with just being aware that you’re here. At one level this is the practice of being present. It is something you have to practice, and you may need help or instruction.

It is not a form of being self-conscious, which would interfere with your daily activities. On the contrary, it means being fully engaged with whatever you’re doing at a particular moment. In a sense it’s the practice of remembering yourself at any given moment, which is why Gurdjieff called it “self-remembering,” recalling what you have always been, from the beginning of time, within yourself. It’s trying to be open inwardly to the real “I” within myself. I believe that’s what Gurdjieff meant when he said, “Remember yourself always and everywhere.” It’s a seemingly impossible task, but just the attempt to do it can be transformative.

Gurdjieff wanted his teachings to move the student toward a profound experience of stillness and presence that points in the direction of God. I wouldn’t say it’s the same as God, but it takes you in that direction, whereas much of contemporary religion generally does not. Through Gurdjieff’s method I became absolutely certain that something we call “God” exists, even if it remains ultimately inexpressible.

Miller: You refer in your writing to the “work of listening.” What is it?

Needleman: It’s opening yourself to what another person is saying without reacting in defense. In one of my classes I had a very serious fundamentalist student, unable to accept any idea that disagreed with his literal interpretation of the Bible. I felt I had to understand him, so I started listening to this fundamentalist and responding, respectfully, with my point of view, even as he rejected me entirely. You could say that was my spiritual discipline at that moment: to let that rejecting point of view in instead of reacting to it. And as I did so, I began to feel both his humanity and mine in a new way. We came out of that class with a deeper respect for each other. That’s not to say that either of us changed his views, but that didn’t matter. It was an exchange that allowed us to relate as two human beings rather than opponents, and that was an important experience.

Miller: In your writing you distinguish common emotions from “deep feeling.” What is the difference?

Needleman: I think our experiences of real feeling are rare. By “real” I mean non-egoistic feeling, feeling that isn’t an expression of the conditioned social self. The personality experiences many emotions that have real energy, but they are not the same as, say, a sense of wonder that transcends the ego. We all experience real feeling from time to time. Sometimes, when facing the death of a loved one, we experience a grief that is non-egoistic. It may eventually turn into fear or anger or even guilt, but at least for a while we become truly quiet in our sorrow. In that state you’re a different person; no one can annoy you, and nothing is a problem. Sorrow or grief, at this level, is not a negative emotion. It’s an impartial, nonpersonal state of being, a vibration that comes from inside yourself. It has that quality of wholeness that’s so much bigger than our egoistic concerns. It’s infused with a great compassion and not limited to your personal, self-preserving perspective.

The deep feelings associated with God have nothing to do with personal gain or loss, with getting what you want or being disappointed that you don’t, with battling or defeating your enemies, with success or failure. Deep feelings are outside of time and beyond our daily concerns; they are impersonal and impartial, yet powerfully experienced within ourselves. They connect us with a sense of joyous obligation without any reference to religious rules or customs. Real love, deep joy, and genuine grief all have this transcendent quality.

Scriptures often express deep feeling, when the writing appears to come from a non-egoistic state. You can find this in the Old and New Testaments, the Upanishads, the Tao Te Ching, and The Cloud of Unknowing, and if you can’t understand or grasp it at first, then you may need to go live a little more and come back later. It can’t be explained to you any more than music can be explained to you. I can show you melodies and chords and talk about music theory, but that’s not going to enable you to grasp Mozart. The same goes for the deep feeling that connects you to God.

Without the experience of deep feeling, you’re likely to suffer from a fundamental sense of meaninglessness. I’ve seen it countless times in the young people I’ve taught throughout the years. When push comes to shove and you get down to the real question of their hearts, it’s always some form of “What’s it all about? Why are we here? What are we doing? Is there something else we’re meant to be doing? What kind of bad joke is this life we’re living?” Every human being thinks about these questions sooner or later. The only real answers lie in a deep feeling that shows us what meaning is, that gives us the experience of God rather than a belief in God. When you’re far from that meaning and experience, you’ll be depressed.

What we call “God” is what actually gives meaning to life. Everything else, like fame, money, or power, is what traditional religion calls an “idol.” Idols give you temporary gratification or distraction but leave you with the feeling that “you can’t take it with you.” The experience of God cures that, not by making you feel immortal, but by connecting you with what’s timeless, both out there and within yourself. So the meaning of life is not words but experience. If you want to translate it into words, go right ahead. Just remember that the words are not the experience.

People are recognizing that something is missing in religion as we know it, and also that something is missing in their lives without a belief in something greater than themselves.

Miller: The last couple of decades have shown a rapid increase in the number of people who identify themselves as “spiritual but not religious” — as high as 70 percent among young adults. Do you think this is good news?

Needleman: I think it’s a very good sign. It means people are recognizing that something is missing in religion as we know it, and also that something is missing in their lives without a belief in something greater than themselves, something that exists both inside and outside. So much of what preoccupies us doesn’t really matter. We’re all very concerned about money, for instance, and money is important, but in the long run it’s deeply unsatisfying as a priority. Science is tremendously powerful in our culture, yet any good scientist knows that the more we figure out, the more we discover how little we know. So science ends up deeply unsatisfying as well. Much of the technology it produces only enables us to do things faster while ending up even more alienated — not to mention creating more problems than it solves.

We live in a very complicated, high-tech society that gives us Facebook and Twitter, yet leaves us longing for real human connection. Something more, something greater needs to pass between us, and that’s what people are looking for when they seek their own “spirituality.” For this to happen, we need to pay a higher quality of attention. That’s not the same as simply paying more attention to each other; it’s a transformative energy that passes between people when they genuinely listen to each other. Television appeals to the lowest common denominator by portraying social and political debates as people shouting at each other. Everybody on TV exercises his or her right to express dogmatic beliefs at top volume, but we almost never see a model for deep, attentive listening. The value of genuinely being in each other’s presence, regardless of whether we happen to agree, seems to be almost completely lost in our social discourse. That’s why we get so little meaning from all our public arguments. It seems that we don’t even know how to facilitate genuine presence, the kind of authentic being-with-each-other that may actually bring about real, positive change.

As a culture we’re coming to face our spiritual poverty, which is an important first step, as it would be for any seeker. But we tend to look at religion the way we look at football — we want our side to win! Even atheists want science to win over God. I’m all for scientific atheism in the sense that it encourages people to question the egoistic content of religion, but we don’t need to throw out God so much as we need a new concept of God: a concept that’s free of myth, superstition, and fear, and that brings us into real presence with each other. When that happens, it transforms everything, at least for a moment.