My mom loved games so much that, before she died, she asked us to place some of her ashes in the Boggle egg timer. As a mother of seven, she bonded with her children through games. She didn’t dumb you down by letting you win. She also didn’t whoop your ass and leave you feeling crushed. She offered tips if you wanted them and allowed you the glory of victory if you were paying attention. Winning or losing was less important to her than spending time together. During a good game, she was invested in the moment with you.

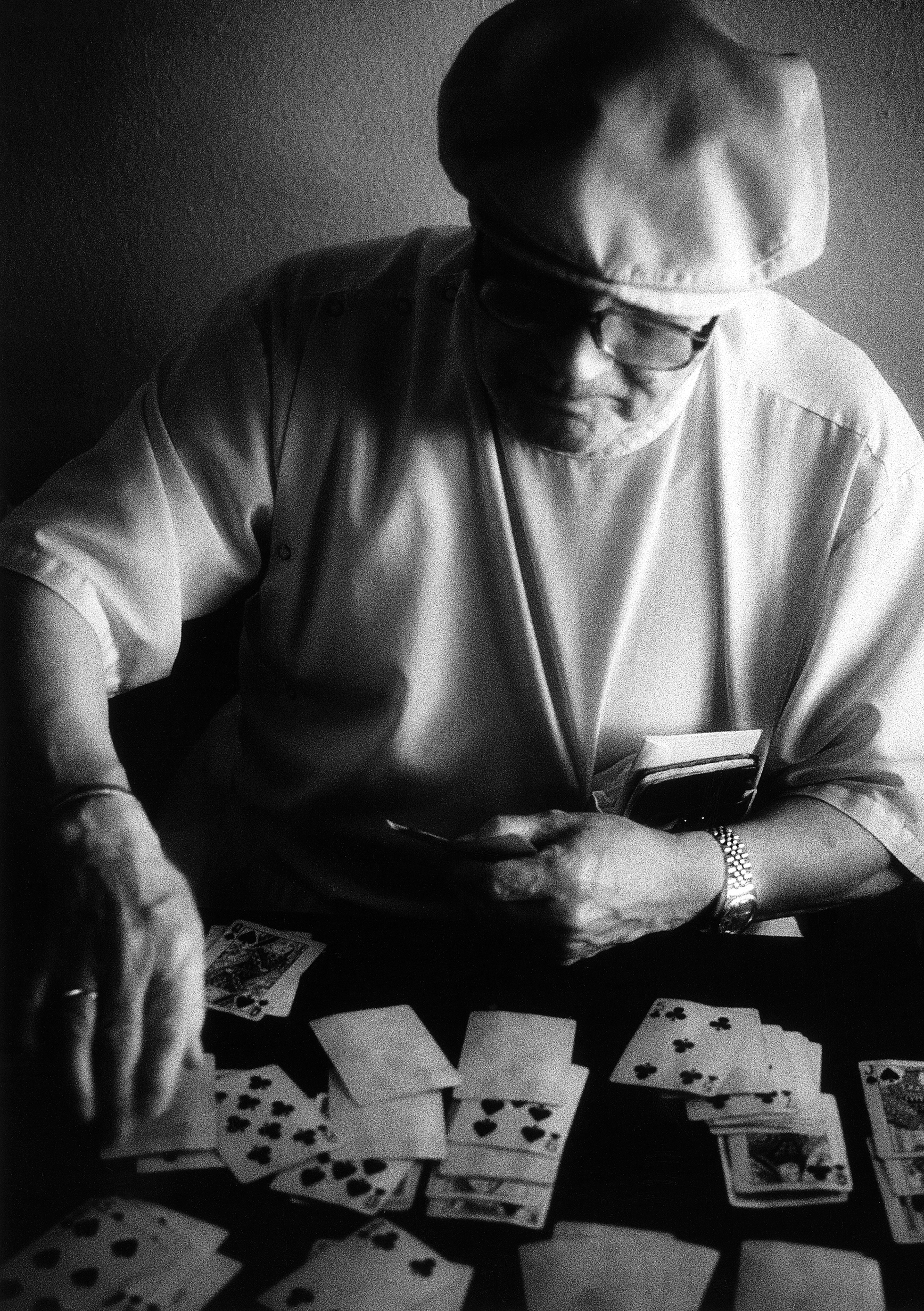

Later in life, she developed Alzheimer’s. When I’d visit her in the nursing home, I often took along a deck of cards and played solitaire on her bed, hoping to spark a flash of recognition in her. One day, feeling overwhelmed, I missed playing an ace. Mom gently reached out, placed it where it belonged, and pointed to the two of hearts. She then leaned back and returned to that world I could not reach.

Ann Davis

Stewartstown, Pennsylvania

Uncle Dave was our church pastor, and all the women thought he was next to perfect. He had blue eyes like Paul Newman and a full head of wavy hair. He would even show up at Ladies’ Aid meetings, sealing his image as a man who could do no wrong. As an uncle, however, he was stern and intimidating. Those blue eyes could deliver a withering look that grown-ups never saw.

One Sunday after dinner at Uncle Dave’s house, somebody suggested a game of croquet. We had two teams — Uncle Dave and my cousin Lisa versus my dad and me. My dad had a deep laugh and a big heart. He worked for the parks department, digging up tree stumps and planting tulips. He was warm and friendly to everyone, no exceptions.

During the croquet game, my uncle hit my ball with his ball. According to the rules, he could then knock my ball in the opposite direction. He hit it out of the backyard and down the sidewalk: it would take me at least three turns to get back in the game. Nobody said a word. I didn’t let him see me cry. When it was my turn again, I mustered my courage and said, “Uncle Dave, I’m only five.” I waited to be reprimanded; no child ever talked back to him. I was amazed when nothing happened. I decided that somehow my father’s presence protected me.

Four years later my dad died. My mother had to change her will to name a guardian for me, in case she died while I was still a minor. She chose Uncle Dave. While he signed the papers, Dave commented that he was taking over my father’s role now. “You may be my uncle,” I said, “but you’ll never be anything like my father.” Nobody scolded me. They knew it was the truth.

Marcia K.

Chicago, Illinois

In the summer of 1993 I went to Romania as part of a study-abroad program. While there, my group visited an orphanage in Cluj-Napoca. Before the visit, we went to a toy store and bought toys for the children. The selection was extremely limited, but we settled on an assortment of simple toys, including a plastic duck with rings that could be tossed over its neck.

When we got to the orphanage, we were met with mild hostility by the staff. These children, I was told brusquely, were not available for adoption. Their parents were alive but either in jail or too poor to maintain custody. (I was told later that some parents reclaimed the children periodically and put them on the streets to beg.)

On the playground, the children hung from the arms and legs of the few beleaguered workers. They all wanted to be held, or at least touched, by an adult. After picking one child up, I was lost in a sea of upraised arms. I was grateful for the chance to express affection, but their desperation haunted me, and has ever since.

No children were playing together. If a child sat on a seesaw and another child dared approach the other side, the first child would scream and yell at the intruder. Thus the three teeter-totters were all stationary, guarded aggressively by children using them as seats.

The duck toy was doomed. The children would not allow us to demonstrate the game. Rather, they clamored for pieces, then ran from the group, clutching a precious ring or the duck to their chest. Occasionally one child would approach another and take a ring by force.

I now have a two-year-old daughter. I worry a lot about making the right decisions for her: Should she take Suzuki violin classes? Did I do an art activity with her today? Should I be working with her on her letters? Is she getting enough socialization? Should I work a second job to pay for part-time preschool?

A few days ago my husband and I took our daughter and her friend to the park. We sat on the seesaw, one adult and one child on each side. The girls were completely delighted, smiling and laughing as we went up and down, again and again. I thought of those Romanian children and took bittersweet comfort in how complete my daughter’s life already is.

Cara C.M. Althoff

Portland, Oregon

In the midsixties I was a stay-at-home mom with four children living in a small tract house. Though my husband had a good job, we struggled financially. When he got paid, he gave me some money to run the household and kept the rest for himself. One Friday he left his cash on the dresser. I counted it and was amazed by how much he had compared to how little he gave me. I snuck a twenty, hoping he wouldn’t notice. He didn’t. The next payday, he again left his cash on the dresser. I snuck another twenty. No reaction. This became our routine.

One Friday there was no cash on the dresser. While my husband was in the bathroom, I scavenged around, searching his pants pockets and jacket. No money. After several paydays went by like this, I realized that he was hiding his cash. He had to get it out sometime, though, so I began to watch him carefully. One night he stayed in the living room to look for a book. The next morning, before he awoke, I combed the room and found his hiding place in a wall unit. My heart raced. I snapped up a twenty.

Now the real game had begun. Each payday I found the money stashed in a different location: in a tissue box, under the living room rug, in the kitchen cabinets, under a toy in our daughter’s bedroom. One morning my husband stood at the ironing board ironing a stack of bills: he’d stashed his money in the dirty clothes, and I’d inadvertently washed it. We both laughed our conspiratorial laughs and said nothing.

I became more interested in winning the game than in getting the money. When I didn’t find it for many weeks, I started to get depressed. Then my husband casually remarked about a “wall safe.” I examined the artworks in our living room and found that one had a deep frame, creating a kind of hidden shelf. Exhilarated, I rewarded myself with eighty dollars.

Eventually my husband grew tired of playing and announced that he would leave the money out and count it before going to bed. The game was over.

Gail B.

Hooksett, New Hampshire

Four years ago, my dad learned he had a brain tumor. Within days, he could no longer construct sentences, swallow properly, or move his right side.

Because part of his throat was paralyzed, eating and drinking became a struggle. On good days, he could raise his own fork. On bad days, I held his head up while my brother lifted a glass to his lips.

Dad’s hydration became my obsession. I recorded how much he drank and listened for the rattle of water in his windpipe after every swallow. At night, when I held his toothbrush for him, his tongue seemed shrunken and dry. His skin shriveled and turned white. Light seemed to shine through him at the end.

Even before his illness, water had been a personal issue for us. Dad remembered Idaho’s rivers when they were thick with fish — before dams stopped the salmon migration. Growing up in New Mexico, I saw a pinyon forest ripped out for a water-needy golf course. Now I live in Owens Valley, California, a community sliding into desertification. Natural springs, grassy meadows, and water-dependent plants are slowly disappearing. The valley’s smooth soil crumbles into sand. Everywhere I look, I see Dad’s dry tongue and translucent skin.

When I go on a long run, I often play an idiotic game: I take an unfamiliar route and tell myself I will find water along the way to refill my bottle. Before he died, Dad survived with only sips here and there. After a century of surface-water diversions and thirty years of groundwater pumping, the valley too survives on sips. I should be able to do the same.

Sometimes I go many miles without finding water. As I become dehydrated, my calves cramp, my cheeks become encrusted with salt, my fingers swell into sausages, and I start to stumble. I find myself trying to suck dampness from an empty bottle, wondering why I play such stupid games. I look at the tumbleweeds and bare sand. I think of my dad and his dry husk of a tongue. I have no idea what it is to be truly thirsty, and for that I feel both gratitude and guilt.

Ceal Klingler

Bishop, California

At the age of eleven I started watching my mother and her friends play bridge. Once I began to understand the game, I found it fascinating. If one of them had to leave early, I’d take her place.

In college I played bridge once a month at the Cosmopolitan Club. One Friday my partner, a senior named Alex, was so impressed with my card playing that he offered me a ride home. That’s how I started dating my future husband.

Throughout our twenty-year marriage, bridge was one of our regular pastimes. After the divorce, I didn’t play for fifteen years.

My son Douglas is a professional dancer and the only one of my children who loves to play cards. He and his friends in Los Angeles started asking me to teach them bridge, but I wasn’t interested, so I made excuses.

By the mideighties, Doug had experienced one tragedy after another, losing friends, ex-lovers, colleagues, and health-care providers to AIDS. Then Earl, Doug’s closest friend, was diagnosed. “I feel such a comfort when you are in town,” Earl said to me. That’s when I decided to teach “the boys” bridge.

Every few months I flew down from Oakland for a marathon session, playing all day Saturday and Sunday. I drew up a teaching plan but soon realized that these young men did not take the rules and conventions as seriously as I did, and I yielded to a more casual form of bridge. Expertise was not the goal; having fun was. So was having a place to talk, and occasionally cry.

After a while the group dwindled to four regulars: Earl and Chris, both of whom were sick, and Doug and his friend Jeffrey. It was a bittersweet time, getting close to people I knew I would lose.

Chris and Earl both eventually died. Now Doug and Jeffrey are the only bridge players left. When I travel to LA, we rope my ex-husband into being our fourth. After all these years, he and I are partners again, if only at the bridge table.

Tita Caldwell

Oakland, California

The local paper calls my coach “the Vince Lombardi of girls’ softball.” We’ve creamed every team we’ve played. One night Coach arranges a meeting with our families: he has decided to move the team from the city league to a national softball association.

“There’s one condition,” he says to our parents. “If you want your girl to stay with this team, she is mine. If that’s a problem for you, take your daughter home now.”

This is not a problem for my family. My father is a violent alcoholic who threatens me with foster homes. My mom, overwhelmed by his rage and unequipped to raise three teenagers, screams about having a nervous breakdown. They don’t want me. I am his.

Every day my teammates and I do two hundred push-ups, proud of our physical prowess. In the middle of practice, while we’re fielding short hops from the machine Coach sets at seventy-five miles per hour, he stops and orders, “Drop and give me fifty!” No one wants to struggle and have her weakness show a “lack of respect for this team.” No one wants to be the one his eyes fix on when he shouts, “Don’t waste my time, ladies!” We know that girls all over the city want out of the bush league.

When we practice outdoors, I dive for the ball and come up covered in mud mixed with blood, gravel, and torn scabs. I pull the ball into me, wind up, and rocket it back to him. When it rains, we practice indoors, where the ball spins off the waxed gym floor. “Get in front of the ball!” he yells. “Don’t be scared of it!”

I take a ball to my breastbone. I take it on the chin and bite my tongue and taste sweat and salt.

Our team wins first place in the state and earns a slot in the national tournament. We hold bake sales, car washes, and bottle drives to pay for airfare. I ride a DC-7 from Oregon to Houston. The minute I step into the Texas heat, I am immediately covered in sweat.

At the playing fields, I’m terrified. The other teams are fast and skilled, as tough and ready as we are. For the first time, I wonder if I am good enough.

We lose the first game to a lesser team, because we aren’t used to their psychological tactics. They scream, “Goodbye, Ora-Gone!” when we are up to bat. But it’s best out of five, and we advance in the tournament.

In our final game against a team named Sid’s Forces, I catch a fly ball in right field and throw out a runner at third base. Still Sid’s team beats ours three games to two. We take sixteenth place out of thirty-two teams.

As we shake hands with Sid’s Forces, our coach is right behind me. Sid nods to him and says, “She’s a rock.”

Coach puts his hand on my shoulder. “Yes, she is.”

Rachel Indigo Cerise Brown

Portland, Oregon

I missed fourth grade because my mother left my father and took me to live in the Bahamas. She told my teacher she would homeschool me, but we did only a few multiplication tables before going to the beach every day.

On my first visit home to see my father, I learned that he hadn’t been living in our house, but instead renting a one room basement apartment: a sad place with a grille across the only window. Even at nine, I realized he wasn’t doing well.

We stopped by to check on our old house, which had been empty for months. As Dad and I walked in, I breathed in its smell and wished I still lived there. Several stacks of mail were waiting for us. In one pile Dad found a big mailer addressed to me. I knew what was inside: I’d sent away one dollar and several box tops for it before our lives had changed.

It was a Froot Loops dry-erase message board with a plastic felt-tipped marker and a picture of Toucan Sam, the cereal’s cartoon mascot, on the bottom. Froot Loops cereal was a staple of my diet. I ate it for breakfast every morning, and sometimes again for dinner.

For a couple of hours, Dad and I sat in our kitchen, playing hangman on my Froot Loops message board. We talked about little other than picking vowels and consonants. It was probably the most time I’d ever spent alone with him.

Jeanne B.

Boston, Massachusetts

“I am counting to ten. You have that much of a head start.”

“But, Dad, I don’t want to play this game.”

“Five. Six.”

“Please, Dad, I don’t want to.”

“Seven. Eight.”

I know better than to be standing here when he reaches ten. I take off running.

I run until my legs begin to hurt and I’m breathing hard. Then I hide in some bushes, close my eyes, and feel my breath slow. I hear women’s voices and see their legs walk past. They do not stop to ask what an eight-year-old girl is doing hiding in the bushes, so I must be hidden really well. Still, my father is a marine and a good tracker. I must be careful, stay still, and breathe silently. My father can hear the smallest noises.

After a while I’m so tired I can’t keep my eyes open. I close them and ask the hedge and my guardian angel to watch over me if I fall asleep.

A pain in my neck wakes me. The sun has changed position. I have to go to the bathroom. Am I safe? Is the game over? Is my father waiting to pat my head and say, “You’re a good marine, kid”?

I decide that if I wait for a blue car to go by, it will bring me good luck. Two cars go by: silver and black. The next one is red. At eight cars I begin to worry about the time. Being on time for supper is part of the military discipline my father says we will live by or else “ship out.”

Car number nine goes by, white. Then number ten is close to blue. Now I can come out of hiding.

Where is my dad now? In the house, I’ll bet, fixing something that’s broken or reading his newspaper or having his beer. I hope he and my mom are not fighting about his drinking. He is going to be proud that I have become such a good hider. He wants me to become the best marine there is.

I walk back up the hill feeling pretty good and go around to the back door of the house to climb the stairs. (We live on the second floor.) I’m almost there. If I count stairs by twos, I’ll have even more luck: two, four, six.

He grabs me from behind, covering my mouth so tight I cannot breathe, and lifts me off the floor in a crushing hug. In my ear he whispers, “You thought you were safe, didn’t you? You thought you won, didn’t you? Well, you don’t know who you’re playing with. You’re playing with the big boys, and you lose, kid. You think you’re a smartass, don’t you? You think you can beat your old man. Think again. I win! I always win!”

I am plastered against his chest. I feel his hand inside my shorts, my underpants.

“What do we have here, now? Is this the prize for the winner? I think so. Let me see.”

I want to scream, but his other hand is over my mouth.

“You love this, baby, don’t you?”

I try to nod, but I can’t move my head. I want to cry, but marines are not allowed to.

“Don’t tell your mother. If she knew what you were doing and how you keep asking for this, she would send you away to where crazy kids are taken. Don’t worry. I won’t rat on you. Supper is probably ready. She’ll have a fit if you keep her waiting. I’ll be there in a minute.” He smooths my hair. “Remember, kid, I always win.”

My body moves without me. Through the screen door I see my brother and sister at the table, my mother at the stove with her apron on, forking spaghetti onto a plate. She frowns. “You know the rules. You’re late. Sit down before your father finds out.”

Carole U.

Franklin, Tennessee

My four-year-old son David has spinal fluid leaking from the incision in the back of his shaved head, where a few days ago surgeons removed a malignant brain tumor. The emergency room staff and the on-call physician have decided that the situation is not dire enough for the neurosurgeon to cut his Saturday golf date short, so here we sit in a small ER admissions room. It is going to be a long day.

I take stock of the room: a chair, the hard examining table with pillow and blanket, cupboards, latex gloves, lighted ear-nose-and-throat scope, examining-table paper, and rolling stool. Dave has a Ninja Turtle in his hand and clutches his blue stuffed bunny tightly. He is not in any pain, but the continuous flood of spinal fluid soaking the back of his shirt is making him fussy and uncomfortable. He is scared, angry, and clinging to his bunny and me for all he is worth.

I do a quick recalculation of the room’s possibilities. We could play pillow toss or hide-the-Ninja. We could blow up the latex gloves like balloons or stretch them over our heads and pretend to be chickens. We could make shadows with the light on the ear-nose-and-throat scope or take spin rides on the rolling stool. But first I need to draw Dave out.

I slide my nose up the side of his neck, sniffing him and lightly nuzzling his ticklish skin. Then I quickly back off. Aggravated, he waves his free arm, trying to make me go away. I zero in again, closer this time, with more determination: sniff, sniff, sniff.

He wriggles. I see life rising in him, but he doesn’t want me to know.

“Hey!” I yell, drawing back and looking at him fearfully. “There’s an animal in here, and he’s sniffing me!”

“Mo-om,” he says gravely, “that’s you sniffing at me!”

“No way,” I say, looking behind the exam table and in the cupboards. “I’m telling you there is something in here.” I pause for effect. Then I squeeze him tight in feigned panic. “It’s trying to get me!”

In his eyes I see the balance between despair and joy slowly shifting. “Mom!” he says again, not quite as peevishly, with a hint of uncertainty. A sly smile starts in one corner of his mouth, then moves up his cheeks, into his eyes.

He slides two fingers up my back, behind my neck, in a clumsy four-year-old’s tickle. “Look out! He’s behind you!”

We will not return to despair this day, no matter how hard things get.

Anne E. Visser

Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina

My older brother loved Monopoly. On summer days when it was too hot to be outside, he’d beg me to play. Sometimes I would give in because I didn’t have anything better to do, or because I felt sorry for him. He didn’t have many friends.

At first I’d get caught up in the game, trying to buy at least a few good properties and not get stuck with just the purple ones. But it wouldn’t last. There weren’t many things my brother was good at, but he was good at Monopoly. He always ended up with Boardwalk and Park Place, where he would put not one, but several hotels. At that point I would quit. Furious, he would insist I keep playing, but I saw no point if I was going to lose. I see now that by refusing to continue, I took away his chance at victory.

Now in his fifties, my brother hasn’t won much in life. He’s never had a relationship that lasted more than a few years and hasn’t worked in a decade, letting our mother support him. Maybe he would have believed in himself more if I’d let him experience the joy of winning.

Mary D.

Wheaton, Illinois

In 1982 I worked in a VA hospital on a unit for schizophrenics. Treatment consisted of Thorazine, group therapy, individual therapy, and major tranquilizers. Dysfunction ruled. Group therapy was a long period of silence punctuated by mumbles, grunts, and farts. It got so bad I decided to try basketball with them instead. The patients didn’t get it, preferring to use the ball as a missile.

Next I tried volleyball, and this time I let the patients make the rules. They decided it would be me against them. Ten schizophrenics against one doctor: seemed fair. They lost most of the early games. Then something happened. Their hostility turned to friendly insults, banter, and finally fun. They started winning almost every game.

Late one evening a patient named Fred, who had made some big plays earlier on the volleyball court, told me that at 33 1/3 he would be on 45 taking a 78 to Venus. I thought this was one more delusion, the numbers taken from the speeds on an old record player. The next morning, though, Fred turned up missing from the locked unit.

The police later reported that at around 4 A.M. Fred had stepped in front of a truck on Route 45, holding a cardboard sign with the number 78 written on it. The volleyball games stopped after that.

Two weeks later I walked into the hospital cafeteria and found the unit’s volleyball team, minus Fred, all at one table, laughing and eating ice cream. They weren’t supposed to be off their unit. When they saw me, they fell silent. Then one asked, “You aren’t going to turn us in, are you, Doc?”

I told them I wouldn’t. They said they were talking about Fred. “ ’Cause Fred got out!” someone said. The whole table burst out laughing. Laughter is good medicine. So are games, for people who happen to be schizophrenics, and for their doctors, too.

Douglas Gill

Clarendon Hills, Illinois

“Thimble in sight” was our winter-evening game. My mother would get her thimble from her sewing box in the bedroom, and we’d take turns hiding it, my father first. While my mother and I carefully covered our eyes and listened for clues, he tried to throw us off track. He would fumble near the record-player cabinet, pause by the windows, rattle a lampshade. The only rule was that the thimble had to be hidden where it could be seen without moving anything.

When I opened my eyes, I’d scan the room to see if I could spot it easily. The best hiding places were in plain sight. One night my father hid the thimble on top of the shiny nut that held the lampshade in place. My mother saw it and quickly said, “Thimble in sight,” then looked in another direction while I continued to search. “Getting warm now,” my father said. “No, colder . . . colder . . .”

It was a gently competitive game that reinforced our connections to one another. It also held uncanny echoes of my family’s secrets, known to us all but invisible according to the rules we followed.

Name Withheld

I used to coerce my little brother into playing one-on-one whiffle ball with me. I took these games very seriously, chalking batter’s boxes and foul lines in the grass behind our house, turning T-shirts into makeshift uniforms, and keeping meticulous records of hits, runs, and other statistics. It was impossible for me to relax and enjoy playing. I needed to win, to dominate my smaller, weaker opponent. When I lost, I blamed it on injuries, bad calls, or inclement weather. I could never accept that my brother might be my equal.

The summer my brother was twelve and I was fifteen, he was pitching in a tight game and called me out on a third strike. (By our rules, the pitcher was the umpire.) Humiliated and angry, I disputed his call. Our argument escalated. When he screamed, “Grow up!” I hit him in the jaw with the plastic bat. He stumbled back with a look of shock and fear. A large pink lump swelled below his ear, and tears welled up in his eyes.

I apologized profusely and begged him not to tell our mother. I admitted the pitch had been a strike. I offered him baseball cards and proclaimed him the winner.

“Go to hell,” he whimpered, and he sprinted toward the porch, where our mother enveloped him in her arms. She glared at me and shook her head in disappointment.

I felt terrified and powerless. I knew that my brother and I would never play whiffle ball again.

Chris Malcomb

Berkeley, California

When I was nine, my family moved from Washington, D.C., to a log cabin in western Maryland. My father kept his government job in D.C., commuting ninety minutes each way. We got used to postponing dinner due to a late departure from work or an accident on I-70.

In the early eighties a video arcade opened in our town’s shopping mall, and Dad became chronically late. When pressed, he’d confess that he’d stopped to play a few games of Missile Command. We began eating dinner without him.

Dad eventually lost interest in video games. Then he retired and bought a computer preloaded with the solitaire game FreeCell. He plays it daily. Because the game keeps track of wins and losses, he is able to determine that he has played more than seventeen thousand games. Still he sees it as an innocent pleasure, not an addiction.

Lately, as I struggle to earn a living as a writer, I find myself playing more and more computer games. My weakness is Spider Solitaire. After six months of playing it constantly, I deleted it. Then I bought a new computer that had the game preloaded, and the cycle began anew.

I come up with all kinds of rationalizations for my habit: it engages my mind, develops problem-solving skills, helps me start the writing day. In reality, though, the video game diminishes my spirit. It keeps me — as it did my father — from fully joining others at the table.

Nathan L.

Richmond, Virginia

I am the father of two teenage boys who are enthralled by video games. Often all I see of them is the backs of their heads surrounded by the blue haze of a video monitor. Most of their games have some element of violence and center around saving the world from evil in the form of Nazis, extraterrestrials, or robots. There is no moral ambiguity: they are killing the bad guys. But their games make me uneasy, perhaps because they are so different from the games of my childhood.

My father died when I was eight, and my younger brother and I spent a lot of time unsupervised, playing basketball, baseball, and backyard football. We also invented games that had two consistent characteristics: danger and violence.

One summer we couldn’t wait till December for a snowball fight. After considering several alternatives — apples, tennis balls, baseballs — we decided on charcoal briquettes. They were the perfect weight and size, and the welts they left on our skin only added to the excitement.

Bicycle soccer was our version of polo. All you needed was a soccer ball, bicycles, and a street without traffic — not a problem in our small town. Collisions, however, were a constant problem. It didn’t take many bent fenders, broken spokes, and bloody knees to weed out the less-rugged competitors.

In high school we invented the moped game: one of us would ride our mother’s moped down the street while the other flung a Frisbee at the rider. It combined all the best game elements: technology, speed, skill, and fear. The last time we played, I hit my brother in his right temple, causing him to crash violently. I ran to him, screaming, “Are you OK?” I remember the tremendous relief I felt when I realized he was going to live. I also remember that my mom did not yell at me, but simply comforted us — probably because I was sixteen and crying for the first time since my father had died.

Maybe my boys’ video games make me uneasy because they feature plenty of violence, but no danger. I worry my sons won’t make the connection.

Then I think about other ways their childhoods differ from my own. They’re constantly reminded about the dangers of drugs, sex, and guns. A few years ago they watched people jump from burning towers, which then tumbled to the ground. They have friends on active military duty. Maybe they have enough danger in their lives.

Sam Mullins

Iowa City, Iowa

Before our new school opened, my second-grade class was put on a split schedule. I was a “late kid.” My school day started during the early kids’ recess. I wanted to leave early for school so I’d have time on the playground with the early kids, but Mom never let me. There was too much vacuuming, clothes-folding, and toilet-scrubbing to be done. Besides, she needed me to keep her company and keep her depression at bay. By the time I walked to school, she was napping on the couch, and the lines had already formed on the playground for tetherball.

I loved to hit the tetherball. It felt so satisfying: the violent impact, the heavy popping sound, the way the ball would fly around the pole. But I didn’t get to play very long before the bell rang, calling the late kids to class while early kids continued to play.

One day the bell rang in the middle of my game, and I ignored it. After winning, I stayed to defend my victory, and the one after that. When the final bell sounded, summoning the early kids inside, I trudged to class, late and in trouble.

The following day I again played through the first bell, and even the final bell. The playground emptied, and I continued to hit the ball alone, wrapping the rope tight to the pole, then hitting it the other way to unwrap it. The game was to see how long I could stay there — hitting, wrapping, unwrapping — ruler of my own percussive world.

Daniel Ruark

Los Angeles, California

By fourth grade, my brother Tom could beat my father in chess. Most days after school, Tom sat at the chessboard with a book in hand, practicing moves with names like “Bird’s Opening” or the “Sicilian Wing Gambit.” On weekends he played in tournaments, where he won so many trophies we had to store them in the attic.

When my brother entered MIT, he decided chess was a useless game and shifted his energies to his social life. Though he flunked out after two semesters, he had a reputation for knowing the answers to all of life’s problems. Other students would ask his advice on everything from how to approach a girl to what color to paint their room. All he did, he explained to me, was figure out what people really wanted to do and tell them to do exactly that.

After a few years of living at home and driving a taxi, Tom tried college again, but again lasted only one year. Then he started working at an MIT computer lab, where he discovered the MIT blackjack team, a highly secretive group of players and investors. People often trained for years to get a spot on the team. Within ten months Tom was spending weekends in Las Vegas, gambling hundreds of thousands of dollars in investors’ funds.

At first the casinos were delighted to see him placing ten-thousand-dollar bets at the blackjack table, figuring it was only a matter of time before he lost big. After six months, though, he was still winning far more than he was losing, and the casinos banned him from their blackjack tables. Tom switched to poker, but it wasn’t as lucrative. Then he heard about a company that hired top gamblers to work as day traders.

He now works in an office filled with traders who have backgrounds in either finance or gambling. At the end of the day, the finance experts ask each other, “Did you earn anything?” The gamblers ask, “How much did you win?”

Devon Schuyler

Portland, Oregon

My father and my brother Mitch liked to invent games in which I was the patsy. My earliest memories are of a game I call “Where’s Laney?” Pretending not to see me, my father would cry, “Where’s Laney?” He’d talk of wanting to give me a ride in his truck, perhaps to the dairy, where I might get chocolate milk, or to a nearby farm to visit baby animals. I’d flail my arms. I’d beat my fists. I’d cry, “Here I am, Daddy!” but it made no impression on him as he murmured sadly about my disappearance. I never got to go for a ride. “Where’s Laney?” was a game I could not win.

Mitch often invented games that ended with me abandoned in the swampy woods behind our house, wandering in circles or blindfolded and tied to a tree. In the last blindfold game I played, the other blindfolded players giggled about ice cream and cake being placed in their mouths while I struggled to spit out a lump of cow manure.

“Custer’s Last Stand” was another of Mitch’s games, only he described it to me as “Custard Stand.” I was assigned the role of managing the “stand.” I carefully arranged rocks to be the custard and even gathered shiny leaves to use for money. I was humming contentedly when I was attacked by a tribe of “wild Indians” who pinned me to the ground and sawed off great hunks of my hair. I ran screaming to my mother.

“But it wouldn’t have been historically accurate to let anyone else be General Custer!” Mitch protested. “Custer had curly blond hair.” Mitch said he was sorry; he’d had no idea the other boys would get so carried away. My mother fell for his story, but I’d seen him pass a hunk of my curls to a friend when he’d seen my mother coming.

Another time, after I was kicked by a cow and fell down, scraping my face, Dad and Mitch helped me clean up. They washed me with such care that I should have sensed something was up. (The smell of ketchup should have been another clue.) When my father lifted me up to the mirror, announcing mournfully that my face was gone, I went numb at the sight: a mass of “blood” where my face had been.

For years shame and anger at myself for having been so easily duped kept me from thinking much about these experiences. Now, half a century later, I am helping other abused children deal with shame over the “games” played on them. I’ve learned to understand the game-players too: how, to protect themselves from their own feelings of vulnerability, they attack vulnerable and trusting people close to them, especially those they love. So, in a way, those games may have been evidence of love — love twisted inside out, perhaps, but love nonetheless.

Name Withheld