Growing up in New York City in the early 1960s, I sometimes watched “the fights” on Friday night. That’s how I first became acquainted with a bald, baleful, angry-looking boxer named Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. Like Jack Johnson, another African American prizefighter, Carter had a knack for inciting the ire of white Americans. It’s this ire, he believes, that eventually landed him in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. “I was persecuted,” he says, “less for what I did than for who I was.”

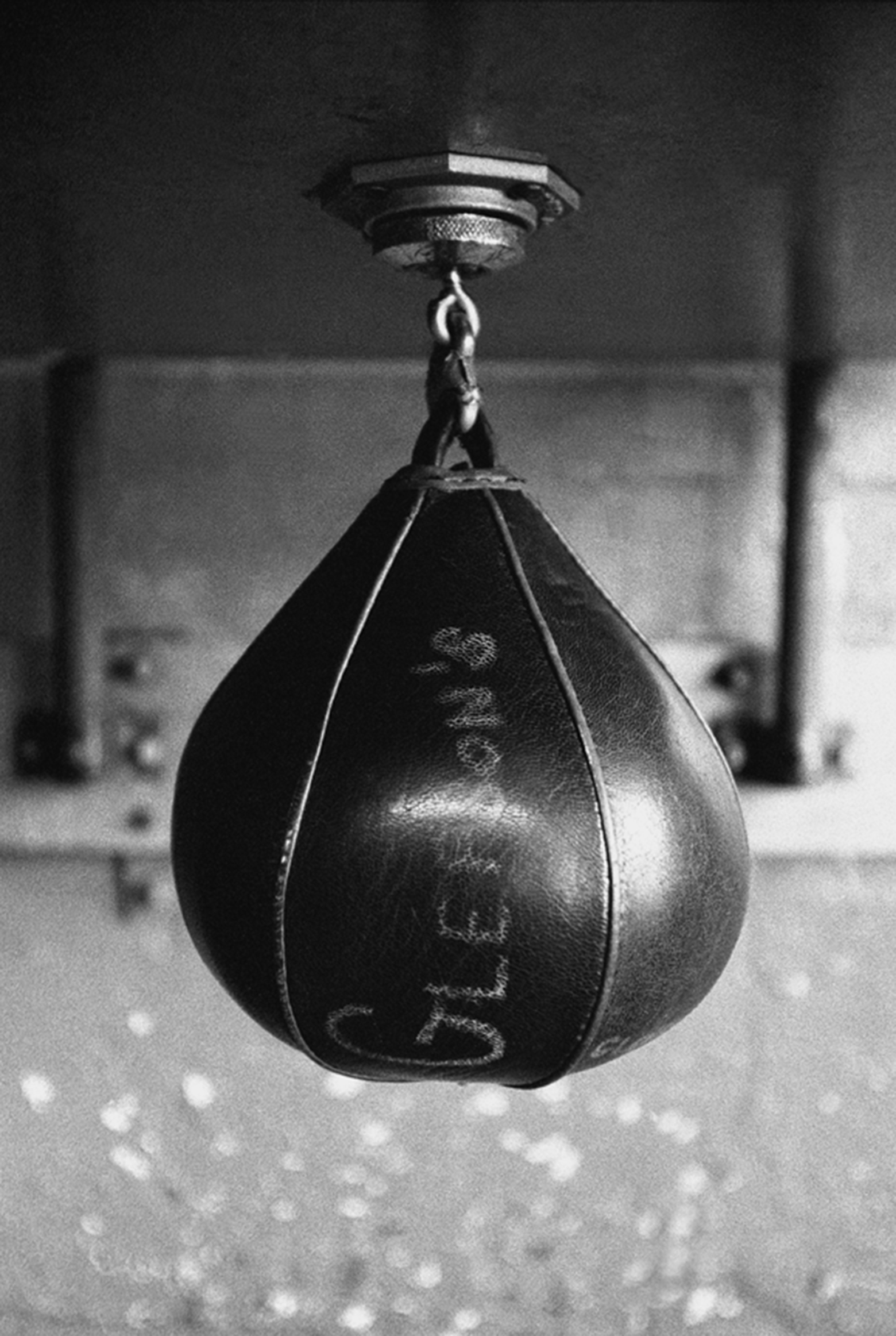

Boxer, prisoner, writer, crusader — Carter has lived an epic life, at once controversial and inspirational. He was born in Clifton, New Jersey, in 1937 and had early troubles with the law. His youthful penchant for brutality resulted in a conviction for a violent purse snatching and mugging. (The memory of his crime still pains him today.) He spent time in the U.S. Army in Germany, where he learned to box. He became a middleweight prizefighter, and from 1961 to 1966 he was a relentless, straight-ahead competitor who was never knocked out. He amassed considerable wealth from boxing and was joint owner of a string of nightclubs in New York and New Jersey.

Perhaps that’s all he would be remembered for had his life not taken an extraordinary turn. In 1966, Carter and a young athlete and admirer named John Artis were accused and convicted of a triple murder at a bar in Paterson, New Jersey. Though Carter and Artis have always maintained their innocence, Carter spent almost twenty years in prison for the crime, only narrowly avoiding execution.

In the midseventies, Carter’s case became a cause célèbre after Bob Dylan wrote the song “Hurricane,” proclaiming Carter’s innocence. The attention helped Carter get a new trial, but he was again convicted and returned to prison. It wasn’t until November 1985 that Carter was released from Trenton State Prison by Lee Sarokin, a federal judge, who found a “pattern of prejudice and racism” at the core of his previous trials. It was the longest-litigated case in the history of New Jersey.

What distinguishes Carter’s story from others about the unjustly accused is the personal transformation he underwent in prison. As he puts it, the man who entered prison was not the same man who came out. After many years behind bars, Carter saw what bitterness was doing to him, and he abandoned the angry persona he’d had most of his life. Then, following his second conviction, he had a vision that he would be freed not by the law, but by a miracle. He began to study the great works of philosophy and religion, which he says helped him “awaken” to a higher level of reality.

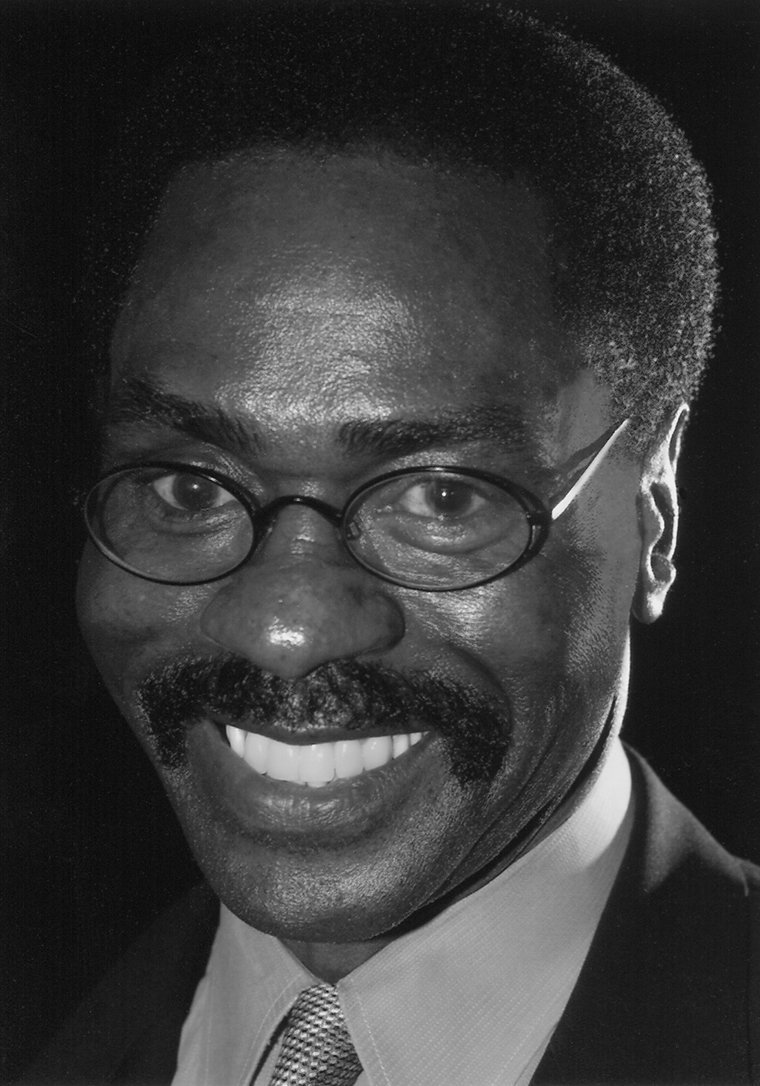

Carter moved to Toronto, Canada, in 1987, two years after his release, and he has lived there ever since. He is currently executive director of the International Association in Defense of the Wrongly Convicted (AIDWYC), an organization that attempts to save innocent people from execution or life imprisonment (www.aidwyc.org). AIDWYC is headquartered in Canada and has offices in the United States and Great Britain. Carter also sits on the board of directors for the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, Georgia, and the Death Penalty Focus of California. He takes no salary from AIDWYC or any other organization, making his living entirely as an inspirational speaker. Two years ago he spoke on the same stage with Nelson Mandela at the first World Reconciliation Day in Australia. “Once Nelson and I saw each other,” Carter says, “we just cracked up. We laughed. He said, ‘We’re here, man. We’re here. We made it.’ ”

Three books have been written about Carter’s life: his autobiography, The Sixteenth Round, published while he was still in prison (and out in paperback this fall from Penguin); Lazarus and the Hurricane (St. Martin’s Press), by Carter’s Canadian supporters Sam Chaiton and Terry Swinton; and the authoritative The Hurricane: The Miraculous Journey of Rubin Carter (Houghton Mifflin), by James Hirsch. This last title was the inspiration for the feature film The Hurricane, directed by Norman Jewison and starring Denzel Washington.

My recent acquaintance with Carter began when my high-school English students, so moved by the movie The Hurricane, invited him to speak to our class. To our amazement, he agreed. He gave a motivational talk, encouraging the kids to pursue their education, and his visit was a transformative event for every student in that overcrowded class. With his dynamic presence, Carter convinced them that their lives meant something.

Speaking to Carter, one is constantly reminded of his religious background. Though he maintains few of his minister father’s traditional beliefs, he will often, in his deep, rolling, sonorous voice, make his points through biblical stories. He acknowledges the influence of the Russian spiritual philosopher Georges Ivanovich Gurdjieff and his student P.D. Ouspensky. Carter’s views are also akin to those of the American Transcendentalists, who understood our day-to-day lives as a kind of waking sleep and saw human errors as the result of our failure to look beneath the surface of things.

I interviewed Carter at his home over a period of three days, roughly coinciding with the seventeenth anniversary of his release. Made wary by his life experiences, Carter refuses to answer his front door himself, but his house, once one gains access, is warm and inviting. There is a room commemorating the children of the world, another devoted to black history, and a meditative flower garden in back.

Carter says he lives in “the eternal present,” yet his memory of past events is palpable, almost physical. (He recalled a boxing match with the great Ibo fighter Dick Tiger by reenacting feints and jabs.) Although his circle of close acquaintances is small, he told me his life is full of “presences” who look after him. At one point, he joined my son Ray and me at a small Toronto restaurant for dinner. I discovered that, during his long imprisonment, Carter learned to live on a minimum of food. Yet when he does eat, he says, he is mindful of the food, savoring every bite.

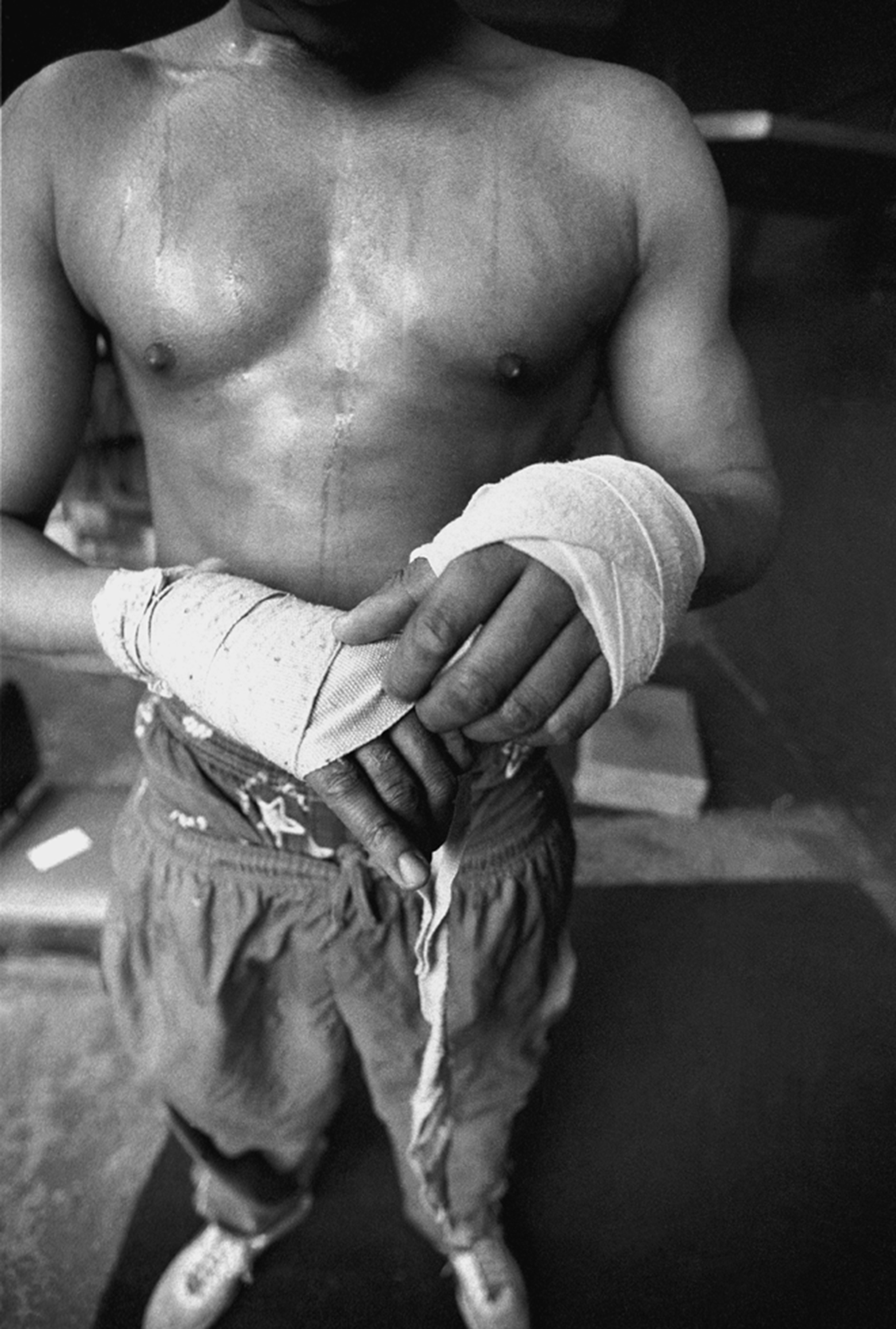

Carter never hesitated to answer a question. While he may have had a brutal streak once, he impressed me as a generous and caring person today. He is charismatic and sharp-witted, still in good shape, with powerful hands, arms, and chest. His confinement, he says, terrible though it was, probably saved him from the fate of many boxers who never knew when to quit. He can be reached at forevercarter@sympatico.ca.

RUBIN CARTER

Klonsky: As a person who was unjustly imprisoned for almost twenty years, how do you manage to avoid bitterness?

Carter: If I learned nothing else in prison, I learned that bitterness only consumes the vessel that contains it. I was angry for a very long time. I was madder than a black bear in mating season who isn’t getting any. I was eating hatred and bitterness and envy as if they were succulent morsels of buttered steak. I was angry at everything that moved. I was angry at the two state witnesses who lied. I was angry at the police who put them up to it. I was angry at the judge who allowed their testimony. I was angry at the prosecutor who sanctioned it. I was angry at the jury who accepted it. I was angry at my own lawyer for not being able to defeat it. I was furious at everyone who helped to put me there.

Bitterness is a part of society’s conditioning. We were all born conscious beings without a single fault. But we were born to people who had already been conditioned by society, and they, in turn, conditioned us. In our society, people are conditioned along tribal lines. I use the word tribalism, not racism, because racism presupposes that there is more than one race of people on this planet: That’s one of the lies we live with. There is only one race of people on this planet, the human race. We all belong to it. What we really have in this society is not racism, but tribalism, and it’s killing us.

One day, I was flying back from the West Coast, and in the seat pocket in front of me was a newspaper folded open to an Ann Landers column. In that column, Landers printed a poem by an anonymous author [later found to be James Patrick Kinney]. I memorized that poem, because it fit my understanding of tribalism. It was called “The Cold Within”:

Six men trapped by happenstance In dark and bitter cold; Each one possessed a stick of wood, Or so the story’s told. Their dying fire in need of logs, The first man held his back, For of the faces ’round the fire, He noticed one was black. The next man looked across the way, Saw one not of his church, And couldn’t bring himself to give The fire his stick of birch. The third man, dressed in tattered clothes, Then gave his coat a hitch. Why should his log be given up To warm the idle rich? The rich man sat back thinking of The wealth he had in store, And how to keep what he had earned From going to the poor. The black man’s face bespoke revenge, While fire passed from sight. Saw only in his stick of wood, A way to spite the white. The last man of this forlorn group, Did nothing but for gain. Give only unto those who gave Was how he played the game. The logs held firm in death-stilled hands Was proof of human sin. They died not from the cold without But from the cold within.

That is the problem of tribalism. It cannot be any different as long as people remain asleep. Sleeping people fight one another. Sleeping people hate one another. Sleeping people go to war with one another. Sleeping people rob, rape, and plunder one another. But there is also a circle of humanity that has woken up and is saying, “I want to know what this is all about and where I am.” These are conscious people. We don’t know these people. We don’t see these people, because we are asleep, and they are awake.

Klonsky: When you say that we’re “asleep,” you mean that we haven’t fully awakened to reality.

Carter: Exactly. Everyone is acting like something that they’re not. The Russian spiritual teacher Gurdjieff tells a story about a magician named Kundalini who owned a flock of sheep, but his sheep kept running away. They didn’t like the fact that the magician wanted to get rich off their wool and fat off their meat, so they ran away. One day, he called all of his sheep together, and he hypnotized them. He told one sheep, “You are no longer a sheep. You are a lion. You’re the king of the jungle.” To another sheep, he said, “You’re a tiger.” To another sheep, “You’re a wolf.” Another sheep, “You’re a bear.” Another sheep, “You’re an antelope.” And on and on and on. After that the magician had no more problems with his sheep running away. They just waited for him to come and take their wool and eat their meat.

On this level of life, we are under the spell of the magician. Whenever we try to identify ourselves, we do it by color, by nationality, by religion, by politics — by words, nothing but words. We act as though we are these things because we don’t know who we are in the first place. Nobody has ever taught us who we are.

When you spend a great deal of time in darkness, in solitary confinement, where everything blends into one, if you’re fortunate, you’ll begin to see things more vividly than you’ve ever seen them before. It may take days, weeks, months, years, but you’ll begin to see things as they really are. You’ll begin to see yourself as you have never seen yourself before. Because when you can’t see outside, you can only look inside.

In a very real sense, going to prison was the best thing that ever happened to me. Without it, I would never have been able to find myself. I would’ve been a baldheaded, mean-looking ex-prizefighter talking through a screen of conditioning, anger, and bitterness.

Klonsky: So, paradoxically, prison made you free.

Carter: Not free, but awake. Freedom doesn’t really exist, because it implies separation, and everything in this universe is connected. There is no separation. This is Nicaragua. This is Israel. I see and feel everything on this earth. When somebody is facing execution, I know it. I feel what that person is going through, waiting to be killed: the ritual, the humiliation. When bombs drop, I feel the pain and the suffering of people. There is no such thing as freedom. What we can have instead is “free from.” We could be free from pain, free from suffering, free from illiteracy, free from poverty, free from violence, free from any of those things.

If you want to escape prison — and we’re talking about a universal prison as well as a physical prison — you’ve got to be very quiet. You can’t alarm the guard. You can’t let the guards know you’re going to escape. You’ve got to find other people who have escaped prison before you and who know the way, and you dig tunnels to go under the wall, or build ladders to go over it. There are physical, mechanical guards that keep us where we are.

Klonsky: You resisted the prison system every step of the way.

Carter: Yes, because I entered prison knowing that I was innocent. I knew that I had committed no crime, and that it made no difference how many juries said I did. I knew I had not done what they said I had done, that I could not have done it. Because I was innocent, I refused to act like a guilty man. I refused to obey the prison rules. I refused to wear prison clothing. I refused to wear the stripes of a guilty person. I refused to eat their food. I refused to work their jobs. I would have refused to breathe the prison air if I could have done so and yet kept my innocence alive. Because that was the only thing I had: my innocence.

My attitude and my belief in my innocence earned me many, many trips to solitary confinement. I spent close to ten of my twenty years in prison in darkness — no lights, no sanitary conditions, no toothbrush, no running water, five slices of stale bread to eat and a cup of water to drink. There was no morning, no noon, no night, just different shades of darkness. There’s a smell down there, down under the ground, filthy waste buckets not emptied in three or four days. It really is a hole. Every fifteen days we were allowed to take a shower, and every thirty days we were given a medical examination.

On my way to one of these physical checkups in what they called the “hospital,” I happened to pass a mirror, and the grotesque image that glared out at me from that glass shocked me back to life. I saw the face of hatred in that mirror. I saw a monster, and that monster was me. And I knew at that moment that if I was going to survive that prison, I had to change. Hatred and bitterness were eating me up.

Klonsky: Why do you think you were kept in solitary for such a long time?

Carter: I was born in 1937, into an openly segregated society where certain people were told, simply because of the color of their skin, “You can’t live here; you can’t work here; you can’t sleep here; you can’t go to school here; you can’t eat here; you can’t drink out of this water fountain; you can’t ride on this bus.” Even in the North it was very clear how America felt about Africans in this country. And then I went into a white prison — at that time they had no black guards in the penitentiary — as a triple racist murderer who would not admit his guilt and would not wear their clothes and would not eat their food and would not even talk to a guard. What do you think they’re going to do to that person? They’re going to try to murder that person. They’re going to try to break that person down to the lowest level they possibly can.

Let me tell you, television representations have nothing to do with the reality of prison. All you have is raw, naked hatred and violence and bitterness. Every day in that prison, my life was threatened. Without question, my being alive at this moment is a miracle. The fact that I am alive and free is a double miracle.

Klonsky: The word miracle comes up often in relation to your story.

Carter: A miracle is nothing but higher laws made manifest on a lower level. When we awaken, we can perform miracles on this earth. That is the kingdom of God: being awake. You have access to it only through yourself. Nobody is going to give it to you. The priest can’t give it to you. The priest doesn’t know. The priest is asleep, and so is everybody else on this level of life. In prison, condemned by history, repudiated by the courts, I was in the one environment that could help me wake up.

I had nothing, absolutely nothing. I was trapped at the bottom, the lowest point at which a human being can exist without being dead: solitary confinement. It wasn’t the end of the line, but I could certainly see the end of the line from there. I had nothing to hold on to, no family, nobody to do anything for me. I asked God to let me understand what was going on, because if I understood it, I thought, I’d be all right.

In the Bible, Solomon had a dream in which God came to him and told him, Ask me for anything and I will give it to you.

And Solomon answered, I am but a little child. I know not how to go out or to come in, but I am a servant of thy people. Give me, therefore, an understanding heart that I may judge thy people wisely and fairly.

And the Deity said, Because you did not ask for the lives of your enemies, did not ask for longevity, did not ask for riches; because you asked only for this one thing, understanding, I will give you understanding. There will not be a person wiser than you on this earth before you or after you.

That’s all I asked for in prison: understanding. And I began to understand that the baldheaded, mean-looking ex-prizefighter who hated everybody — who was conditioned to hate everybody, including himself — he wasn’t me. He was just a mask. He was a persona that I took on because people said I was mean. The more people said it, the meaner I became. Only in prison, when I was stripped naked and bare, did I realize that this person wasn’t me. So I began to grow my hair. I cut off my beard. And I disappeared. That loud, baldheaded, mean-looking man just disappeared. Nobody knew who I was anymore. I went to court in Paterson, New Jersey, and sat in the bullpen, and people were saying, “Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter is coming.” And there I was, sitting right in front of them.

Klonsky: In your autobiography, The Sixteenth Round, you write about how you went and spoke to the electric chair in Trenton State Prison.

Carter: It was executing all my friends, and it almost got me. That’s where my utter abhorrence of the death penalty comes from. You cannot ask for a perfect punishment, such as death, from an imperfect system run by human beings. That’s why opposition to the death penalty has been part of my life’s work since the moment I was released from prison in 1985.

Klonsky: Can you describe some of the work that you do with the wrongly convicted?

Carter: At the International Association in Defense of the Wrongly Convicted, we work to free innocent people from prison. AIDWYC does not defend guilty people. There are other lawyers who will take their cases, and they need to be defended, but AIDWYC defends only innocent people. We determine whether someone is innocent by reading every transcript, going over all the evidence, and investigating the case independent of the police and the prosecutors. Once we come to the conclusion that a person is innocent, we will go to the wall for them. We will insist upon whatever is necessary, even DNA testing, to get that person out of prison.

The average time an innocent person is incarcerated before being exonerated is ten to twelve years. We’ve gotten Donald Marshall out of prison, David Milgaard, Guy Paul Morin, Thomas Sophonow, and many others you’ve probably never heard of. The reason I do this is because, when I needed help, people came to help me. I know what it’s like to be innocent and to have nobody believe you. Maintaining your innocence in prison doesn’t help you at all. In fact, it hurts you. There’s no place in prison for innocence.

Klonsky: How big is your case list right now?

Carter: We have between twenty and thirty ongoing cases and hundreds of applications from all over the world. In fact, we are going to see the Saudi Arabian ambassador in a few days because we have a client, William Sampson, who is on death row there. We have clients in Australia, New Zealand, Vietnam, Japan, and, of course, the United States.

I went to the White House when Bill Clinton was in office to ask him to save one of our clients. A mother and daughter had been arrested in Vietnam after drugs were found in their luggage. They didn’t have any idea they were carrying drugs. The mother was sentenced to life in prison. The daughter was sentenced to death. I asked President Clinton if he would intercede with the president of Vietnam to delay the execution, to give us an opportunity to go over there and prove their innocence. But on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Tet Offensive, Vietnam executed 140 people, the daughter among them. She was executed because she would not admit that she was guilty. Eventually we were able to get the mother out of prison and bring her back to the States. We win more than we lose, but when we lose, we lose a life. It’s devastating.

I refused to obey the prison rules. I refused to wear prison clothing. . . . I would have refused to breathe the prison air if I could have done so and yet kept my innocence alive. Because that was the only thing I had: my innocence.

Klonsky: You appear to be in terrific condition, yet you smoke, you don’t exercise regularly, and you eat a poor diet.

Carter: Let me tell you about food. Because I was unjustly imprisoned, I refused to eat the prison food. My ration of food was an eight-ounce can of soup brought in from the outside once every three days. In order to get to that point, I had to overcome all of my bodily functions. I had to overcome all of those things that tell you that you’re hungry: the growling of your stomach, or a headache, or whatever else informs you that you need something to eat. I had to become a fakir. Fakirs are people in the East who have overcome their physical bodies. The physical body does not know anything about heat, or cold, or being sick, but the mind does, and the mind controls the physical body. The fakirs know this, so their bodies are theirs to do with as they choose. I had to become a fakir in order to survive prison.

Learning to control my physical body was nothing new to me. For the first eighteen years of my life I could barely talk. I couldn’t say two words that made sense to anybody but myself. I had a million words running through my mind, but I couldn’t get one to pass my lips. I would stomp my foot and do all kinds of gyrations trying to get the words out. People would laugh at me. When they laughed, I would attack them. That caused me to have a lot of fights.

Then, when I was in the military in Germany, I met a Sudanese Muslim who was trying to get American citizenship by serving time in the U.S. military. His name was Ali Hasan, and he was a very dignified person. He befriended me and told me that my stuttering was always going to get me in trouble. He said, “If you’re embarrassed to go to school, I’ll go with you.” And he did. I went to school and learned how to talk through one of the first Dale Carnegie courses ever given. People haven’t been able to shut me up ever since. Ali Hasan also introduced me to the boxing coach there, and I started prizefighting in Europe and finally became welterweight champion two years straight.

Overcoming that speech problem and going on to be a professional prizefighter, who had to stay in training all the time, helped me to understand that my physical body was mine, and I should be able to do anything with it that I wanted.

Klonsky: You had moments of doubt and despair in prison. Was there ever a moment when you knew for certain that you would one day get out?

Carter: When I had gone back to prison after my second trial, I was at my lowest point ever. All those celebrities — Bob Dylan, Muhammad Ali, Ellen Burstyn — had gotten behind me, and I’d been let out on bail for nine months during the retrial. But I was reconvicted and sent back to prison. I felt as though I had let everybody down. Everybody had put their butts on the line for me, and here I was back in prison. I stayed in my cell for five years.

One very hot day, I decided to go out on the yard. The yard at Trenton State Prison was built over a paupers’ cemetery. It was rectangular, one-eighth of a mile long, and barren. Just dirt. No shade. Gun towers all around. The sun beating down. I walked around the yard once. That was the longest I’d walked in five years, and I was tired. I leaned against the wall to rest.

While leaning against the wall, I looked across the yard at the wall on the other side, a thirty-four-foot-high brick wall. I saw a pinprick of light in that wall. As I stared at that pinprick of light, it began to quiver and get bigger and bigger. Eventually I could see through the wall. I could see cars passing by in the street. I could see schoolchildren walking to school. I could see all of that through this wall. I thought, I wonder if anybody else sees this. And just as suddenly as the hole had appeared, it disappeared.

But it left an indelible impression in my mind. Maybe that would be my escape, I thought: through that hole. I became determined, right then and there, to find that hole in the wall again. I was going to find it, and this time I was going to walk right through it, even if that hole would deposit me somewhere in infinity. Even if that hole would sear the flesh off my bones, even if that hole meant instant death, I was going to walk right through it. Because anything was better than what I had.

When I went back to my cell that afternoon, I got rid of all my law books. I had been immersed in law for ten years. My case was the longest-litigated case in the history of New Jersey, and I did a lot of the legal work myself. The briefs that were filed to get me out of prison, I wrote. But I gave my law books to other prisoners. One prisoner was shocked. He said, “These are your law books. This is what you’ve been studying for ten years!”

I said, “This is not my way out. My way out is finding that hole in the wall again.” And I found it. That’s why I’m sitting here in Toronto with you today.

Through books, I was able to go on an anthropological expedition, . . . searching for something that was above the law, something that would neutralize the law, because it was the law that had put me in prison, and it was the law that was keeping me there. I had to find a good that was higher than the law.

Klonsky: How did you find it?

Carter: Through books, I was able to go on an anthropological expedition, excavating this world’s cultures and religions, searching for something that was above the law, something that would neutralize the law, because it was the law that had put me in prison, and it was the law that was keeping me there. I had to find a good that was higher than the law.

Klonsky: Whose books did you read? Who influenced you the most?

Carter: I was influenced by a great many people: Einstein, Socrates, Plato, Viktor Frankl, Nietzsche, Émile Zola.

Klonsky: How did you get these books? Were they in the prison library?

Carter: Oh no. I had a friend on the outside, Tom Kidrin, who stuck with me all through prison. He understood that I wouldn’t eat the prison food, and he would bring me a package of canned goods once a month. He was my lifeline. Tom and I are still very close friends. When I was in prison, we used to talk about visiting Jamaica, putting our feet in a blue lagoon, and smoking cigars on the pier. I would dream about that in prison. When I got out, that’s exactly what we did. We went to a blue lagoon, me and Tom, and put our feet in the water and lit up one of those Cuban cigars.

Anyway, after I had that experience out in the yard with the hole in the wall, I told Tom, “Bring me some books.” I wanted something to read besides law.

Tom said, “I’m going to bring you some books that will blow your mind.” He started sending me books on philosophy. When I got to In Search of the Miraculous, by P.D. Ouspensky, who was a student of Gurdjieff, that book struck a chord with me. It suggested that the problems of this earth exist because people are asleep.

I studied all kinds of history and philosophy, trying to find understanding. It was like panning for gold. I began to understand why people had done what they had to me all my life. It was all mechanical. We were all asleep. Even in criminal law there are guidelines and statutes that say you must not punish a sleeping person, and we live in a world of sleeping people. Whatever others have done to you in life, you cannot condemn them, because they did the only thing they could do.

Klonsky: Is that what Jesus meant by “Forgive them for they know not what they do”?

Carter: Yes. He was saying, “Forgive them because they are asleep.” There’s a story about Moses, after he had freed his people in Egypt. While wandering in the wilderness, they happened to make camp in the territory of a certain king. This king heard that Moses, this man of God, was camping in his territory, so the king sent his best portrait painter down to paint Moses’ picture. When the painter brought the portrait back, the king gave it to one of his wise men who was skilled in discerning a man’s character by the lines on his face. The wise man told the king, “Sire, this is the portrait of a mean man, an angry man, a vain man, a man who is full of hedonistic desires, a man who thirsts for power.”

The king said, “How could this be? This is Moses, the man of God. I’m going down to see Moses for myself. If my portrait painter didn’t paint an exact portrait of Moses, I’m going to chop off his head.” So the king went down to see Moses. He found that his portrait painter had painted an exact image of Moses. The king told Moses, “I’m going to chop off my wise man’s head, because he obviously lied to me.”

Moses said, “No. Both your portrait painter and your wise man are correct. In my lifetime, I’ve been all of those things. I’ve been mean. I’ve been angry. I’ve been vain. I’ve been full of hedonistic desires. I’ve thirsted for power. But my greatest task in life has been to resist those things until that resistance has become second nature to me.”

Well, in my twenty years in prison, I resisted everything about that foul abomination to the human spirit. I resisted it until there was no more of it left in me. November 8, 1985 — the date I was released from prison — is my new date of birth. That’s when I began to understand what forgiveness is all about. Before you can forgive anybody for anything, you first have to forgive yourself for being the very thing that you hate. If you can forgive yourself for the things you did while you were asleep, you can forgive others who have done, or still do, those things, “for they know not what they do.”

Klonsky: In your autobiography you say, “Keeping folks like me locked up inside these iron cages forever was big, big business.” Can you elaborate on that?

Carter: I’m old enough to remember when the prison system of the United States reflected its general population. If Italians, for example, were a certain percentage of the population, that’s roughly the percentage of Italians you would find in prison. So the prisons were mostly white. The prisoners were served pasta fazool on Monday, shepherd’s pie on Tuesday, and Irish stew on Wednesday. The black folks were a minority, and they caught hell, pure hell.

In the 1950s, the United States assimilated a lot of its white prison population back into society and began to fill up prisons with black folks, because blacks were telling them, “We want to be able to eat in this restaurant; we want to drink out of this water fountain; we want to ride on this bus.”

At that point, the prison system of the United States became big business. They began loading those prisons up with black people, mostly young black men arrested on petty or trumped-up charges. And they’re still doing it today. According to a U.S. Justice Department statistic, one out of every three black people between the ages of twelve and thirty-seven is now under the control of the criminal-justice system. They have been tagged, just like you would go out on a safari and tag animals. There are more young black men in U.S. prisons than there are in the universities. Do you think that was accidental? No. Eighty percent of prisoners are nonwhite. Eighty percent. The United States today has more than two million people behind bars: more than any other country on earth. They have six and a half million people under the criminal-justice system today. They’ve got a multibillion-dollar budget. That’s why they’re privatizing the prisons. “American justice” is an oxymoron. It’s big business. Justice isn’t blind; it’s got dollar signs for eyeballs.

Klonsky: What do you think of boot camps for young offenders?

Carter: Let me tell you a story. Once there was a little boy whose father promised that he would play with him when he could find the time. The father was a busy man, working all day long, trying to pay the bills, trying to keep his family outfitted in the latest fashions. One Saturday the father was sitting at home reading the newspaper and watching a football game when his son asked him to play as he had promised. But the father was too tired. To buy himself some time, the father ripped out a page from the newspaper that had a map of the world on it. He tore the map up into tiny pieces, gave them to his son, and promised that by the time the boy put the pieces back together, he, the father, would be ready to play.

The little boy went off with the pieces of paper, and the father sat back in his favorite chair, sure that he had all the time in the world to watch football. Five minutes later, the little boy was back, the page of the newspaper totally intact, every piece of the map in its proper place. The father looked at his son in amazement. “How did you do that so quickly?” The little boy said innocently, “On the front of the page was a map of the world, but on the other side there was a picture of a little boy. So I just put the boy back together. And when I turned the page over, the world was all together, too.”

It is not the young people you’ve got to deal with. It is the old people. It is the old people who pass these nasty ideas down from generation to generation and are poisoning the minds of the future; those people who sit in council rooms planning for greater armament and mapping the battle charts. In war, the dead are all boys and girls. So no, it’s not the children you’ve got to deal with. Boot camp is nothing but the perpetuation of violence. I don’t believe in violence of any kind. I don’t think it should hurt to be a child. I’m in my second childhood. We’re all children on this planet. We might think that we’re going to browbeat somebody into behaving properly, but we are not.

Klonsky: What do you think can be done to change the justice system?

Carter: It’s not just the justice system that needs changing. It’s the whole system. When you say that the justice system needs to be fixed, you imply that it’s not working. Well, the system is not supposed to work. The system is mechanical. The system might become more liberal, but that’s really just a reflection of the society. When a society begins to become liberal — and I use that word guardedly — prisoners feel it first. Perhaps they are able to write more than five letters a month, or they may get an extra television or an extra movie, or they may get people coming in and talking about rehabilitation. But when the pendulum swings back and society becomes oppressive, that, too, is felt first in prison. Everything is taken away.

You can’t change the system in the long run. The only thing you can change on this planet is yourself. You cannot change another single thing. You can’t change your mother. You can’t change your father. You can’t change your wife. You can’t change your children. You can’t change your grandparents. You can’t change the government. You can’t change anything. But you do have the possibility of changing yourself, of waking up.

Those who are awake don’t allow the sleeping people to know it, because the sleeping people will crucify them. They don’t want to hear about peace and family and love and brotherhood and sisterhood. They want to hear, “I want mine. I want my money. I want my guns. I want my drink. I want my drugs. I want my football game.”

Klonsky: What would you say to prisoners who have been convicted of a crime they did not commit and are serving time?

Carter: To every human being in prison, guilty or innocent, I would simply say that everything depends upon one’s attitude. The physical body is the vehicle in which we traverse life, but our attitude is our steering wheel. A person in prison finds him- or herself at the bottom of human existence. That’s what prison is: the bottom. Anybody who is in prison has to say, “OK, whatever I’ve done in life has led me to where I am today. Therefore, if I want to get out of prison and stay out of prison, I’ve got to turn around and go back up.” You’ve got to use this time to learn how to read if you don’t know how to read, to learn to write if you don’t know how to write, to learn a skill if you never had a skill. Use this time to better yourself. Maybe on the outside you didn’t have time to go to school, to learn a skill, to take care of your family. Now you’ve got time. This time is imposed upon you. Use it in your best interest. Use it to look at yourself. Use it to become a useful person.

If people like Anwar Sadat, Malcolm X, and Nelson Mandela can come out of prison as better people, able to shape their country and the world itself, then you can, too. And if the people who run these prisons, particularly in America, see that these poor people are going into prison and coming out as geniuses, coming out wide awake, coming out as presidents of countries or as diplomats, then the powers that be will open those prison doors and let all the poor folks out.

Before you can forgive anybody for anything, you first have to forgive yourself for being the very thing that you hate. If you can forgive yourself for the things you did while you were asleep, you can forgive others who have done, or still do, those things, “for they know not what they do.”

Klonsky: Is there anything you still desire from the State of New Jersey or the United States government?

Carter: I never desired anything from the United States government except that it act decently toward all of its citizens, not just a segment, and that it give the disenfranchised an opportunity to go to work and school free of any kind of bullshit. Of course, this cannot happen. It cannot happen because we are on the level of life where everything is mechanical and everyone is asleep.

Klonsky: And yet you transformed yourself as an individual. You woke up.

Carter: That’s the real miracle of it all, that you can wake up.

Klonsky: Looking back, do you have any regrets, anything you might have done differently in your life?

Carter: If I had an opportunity to change anything at all in my life, I would not do it. I love the person I am today. The person who went into prison and the person who came out of prison are two different people. They don’t even look alike. Yet that old Rubin “Hurricane” Carter is still here in me. He hasn’t gone anywhere. He is still here, but he is dormant. On the level of life at which I operate, there is nothing but good. When Jesus was asked, “Who are you?” Jesus said, “I am good.” And I second that: “I am good.” Now, why would I want to change that?

Klonsky: How would you like to be remembered?

Carter: I was a prizefighter at one point in my life. I was a soldier at one point in my life. And I was a convict at one point in my life. I’ve been many things in life, and have many things still to be. But if I had to pick an epitaph to put on my tombstone, it would say: “He was just enough.” He was just enough to overcome everything that was laid on him. He was just enough not to give up on himself. He was just enough to believe in himself beyond anything else in the world. He was just enough to have the courage to stand up for his convictions no matter what trouble his actions may have caused him. He was just enough to perform a miracle, to regain his humanity in a place of living death. He was just enough.