It was February during one of the worst winters on record in Montana, and I had a rampant case of cabin fever. So when my son invited me to spend the summer with him and his family on the Greek island of Alonissos, I said yes without hesitation.

My daughter-in-law, Marinela, is half Greek and has spent every summer of her life at her parents’ rustic villa on the remote side of the island, which is covered with pine and olive trees. When we arrived on July 4, she said it had been cold and wet but was about to warm up.

A week and a half later the mercury shot to 44 degrees Celsius — 111 Fahrenheit. The breeze stopped, and there was no relief. I felt ill and wondered if I would make it.

When I asked Marinela if it could get any hotter, she told me about the time the dust-laden sirocco winds had crossed the Aegean Sea from Libya in 2007: The chirping of the island’s cicadas, generally considered a temperature gauge, became deafening. She and my son heard popping noises and thought it was dying birds falling from the trees. Then they realized that the pine cones were exploding in the heat. As the wind reached the nearby hills, the cones ignited like fireworks.

Elizabeth Carhart

Kila, Montana

My friend Julie and I were baking in the sun on a boat dock at Kings Beach in Lake Tahoe. I was fifteen and full of longing to look cool and meet boys. Just then two honest-to-goodness hippies with sexy long hair, bell-bottom jeans, and bare feet sat down next to us and started flirting.

“How’s the heat around here?” one asked.

“Really hot in the daytime, but it cools off at night,” I responded, hoping I did not sound as awkward as I felt.

He laughed, stripped naked, and jumped in the lake. I was both confused and excited. I didn’t know why he’d laughed, and I’d never seen a naked man’s body.

Walking back to our cabin, Julie told me that when the hippie had asked about the “heat,” he’d been inquiring about the local police presence. Any feeling I’d had of being cool seeped away into the hot pavement.

Marianne Lonsdale

Oakland, California

In the summer of 1958 I was ten years old and living on the fourth floor of a six-story walk-up in the Bronx. My three sisters and I, all under the age of twelve, spent as much time outdoors as we could. With the other neighborhood kids we’d take over the streets and courtyards as our mothers sat nearby at card tables, playing mah-jongg or canasta and keeping an eye on us.

But that summer was a hot one, and the heat and humidity would sometimes become so oppressive that even the dark of night didn’t bring relief. Fans only circulated the hot air. On nights when we could barely breathe, the whole family would tote blankets and pillows up to the tar-covered roof, where the air was cooler and we had a breathtaking view of Manhattan.

Dressed in the flimsiest pajamas we could find, my sisters and I would listen to the sounds of the city below while Daddy read by flashlight and Mom told us stories about growing up during the Depression. Once we quieted down, they’d retreat to a corner of the roof in their folding chairs, smoking unfiltered cigarettes and sharing news of the day with neighbors, who’d also brought their clans up to the “tar beach.”

The ritual ended a few years later when my father bought an air conditioner — a newfangled machine that actually cooled a room with the push of a button. Nobody else on our block had one. I was excited and more than a little proud.

The air conditioner was installed in my parents’ bedroom window and used only at night, to keep the electric bill to a minimum. Now, when it was too hot to sleep, my sisters and I dragged our blankets and pillows to the floor of Mom and Dad’s room. We enjoyed the coolness, but I missed the camaraderie and excitement of sleeping on the roof, the gathering of the building’s families. Somehow the summer night had lost its magic.

Carole Battaglia

Apex, North Carolina

I remember having to get my hair done for church when I was a little girl. The process usually began early Saturday, so my hair would be washed, pressed, and shining on Sunday morning.

The part I enjoyed the most was the actual washing of my hair: my mother’s hands on my head, the way her fingers massaged my scalp. Whether I received this care in the bathtub or standing on an old crate, bent over the sink, the feeling was the same: heavenly.

Then she would take a big towel, rub my hair as dry as she could, and sit me in front of the TV while it finished drying. The images on the screen barely held my attention. All I could think about was that hot pressing comb.

I watched as my mother placed the comb on the gas stove and the flames tickled each tooth. I listened as it popped and sizzled. And I waited, back stiff, hands clenched, sweat beading on my forehead.

When the comb was ready, my mother would take it off the stove and wave it back and forth, smoke clouding the room. Then she’d tell me to be really still while she took a piece of my well-oiled hair and ran the comb through it. As she did this, she’d always blow on my scalp. I didn’t know then what the blowing was for, but now I know it was meant to give me a little relief from the heat.

Nicole Mays

Ypsilanti, Michigan

This big, old, drafty house has been my home for twenty-five years. My former husband and I tried to keep some of the cold air out with insulation, but the windows are single paned and poorly sealed, and a cold draft waits around every corner.

When my three girls were growing up, the hearth in our home was the heating vents. On cold mornings my daughters would stand on the vents, school dresses blown up by the rush of hot air, exposing bright cotton tights. Later I’d vacuum Cheerios out of the grates.

As my girls grew older, they rarely left their winter nests on the vents. As teenagers they had long telephone conversations, listened to music, texted, cried, and (at least once that I know of) made out there. They used the hot air to dry their hair, to warm their jackets, to melt the snow off their shoes. I never understood how they could tolerate the heat.

My youngest daughter, Georgia, a voracious reader and writer, spent many hours reading and doing homework on the vent in the dining room. After her older sisters left for college and her father and I divorced, she seemed to hunker down even deeper into her nest. I always knew I could find her there.

Now all my children have left home, and I live in this big, old, drafty house by myself. This past winter, while running an errand on my way home from work, I got caught in an unexpected rainstorm and was drenched to my skin. When I got home, I dropped my wet jacket and shoes on the floor, found my way to the heating vent, and sat down, feeling exhausted and sad. I missed our old life together and was worried about what the future would bring. I could feel the cold metal of the vent through my wet slacks. Then the furnace lit, and, within moments, the hot air engulfed me. I sat back against the wall and closed my eyes and felt warm and peaceful. I finally understood.

Carey Critchlow

Portland, Oregon

The women in my family kept a secret from me, leaving me to discover for myself what happens to a woman as she ages.

In my forties I awakened one chilly night feeling pleasurably warm. I kicked off my blankets and lay naked in my bed as a heat I’d never experienced before spread through me. I naively thought how nice it was, being warm enough to lie there uncovered, the way I imagined Hawaiians did every night.

The flashes have gotten hotter, though, to the point where I cannot allay the heat but can only surrender to it. I count the seconds until it backs off and leaves me slightly moist and a tiny bit chilled.

There is always a warning first — a tiny, fearful feeling deep in my belly that gives way to what feels like an adrenaline rush, and then the slow spreading of a prickling fever. Once, the heat caused me to lie naked on our snowy patio. The next day my husband and I laughed at the outline of my body outside our kitchen door where I’d melted the snow.

Ruth Wimsatt

Costa Mesa, California

I lived pretty fast as a young woman, always looking for adventure.

In college I had a chance to study overseas. Rather than spend a semester in France or England, I went to the Beirut College for Women in Lebanon. I loved it so much that I ended up staying for two years. Everything felt strange and dazzling: the Arabic language, the food, the covered markets, the rural areas where I learned to squat over a hole in the ground to pee. If it was foreign and a little dangerous, you could always count me in.

One Friday after school, some American and French girls and I took a long, bumpy bus ride to Damascus to visit the Turkish baths we had heard so much about. We were eighteen, nineteen, twenty. We were beautiful and fearless. When we arrived, we found our way to the steam room, where a few old men with towels wrapped around them sat quietly. We threw off our towels and lay naked in that intense heat, giggling, talking, and thoroughly enjoying the newness of it all.

It wasn’t until years later that I found out men and women have separate bath-houses. Those baths were hot, but we were definitely hotter.

Terry Jenoure

Greenfield, Massachusetts

Summers at the girls’ group home in Southside Virginia were sweltering. This was in the 1960s, when we didn’t have air conditioning. Crayons would melt into car seats, and flowers would wilt on their stems by midday. When school let out, the other girls and I would work on our tans. We couldn’t always afford suntan lotion, so we’d slather up with mineral oil, margarine, even mayonnaise.

We saw few men of any sort at the group home. I’d get up at 6 AM twice a week just to glimpse the garbageman’s rippling muscles and inscrutable, dark face. There were only two males on the premises: the married, middle-aged director and the young handyman. A few girls developed crushes on the director and cried when he didn’t acknowledge them in the dining hall or rebuked them for a too-revealing outfit, but the handyman was the chief object of our adolescent desire.

“All them girls need love,” I overheard him remark to the secretary one day. “It could wear a rooster out if that was his aim.”

He was fired a year later after seven girls between the ages of thirteen and seventeen confessed to having had sex with him.

Name Withheld

I drove a New York City cab on the second shift, which, if business was good, ended as late as 2 or 3 AM on weekends. After work that winter I’d turn in my cab on the far west side of midtown and walk home into the wind on dark, barren Ninth Avenue with temperatures in the teens.

My landlords were a thrifty older couple who turned off the heat when they went to bed at 9 PM, and my cast-iron radiators would be like ice when I arrived. I kept a space heater on the floor by my mattress alongside a little black-and-white TV. Every night I’d empty a glassine envelope of heroin into a spoon, add water, and cook. Next I’d drop a tiny ball of cotton into the solution and draw the liquid up into a syringe.

Poking holes in your veins isn’t much fun, but as I squeezed the plunger, a beautiful warmth flowed up my arm and into my brain and dispelled my loneliness the way the sun evaporates the morning fog.

Name Withheld

Mid-August afternoons in Arkansas were ill suited to football. Even the most gung-ho jock did not look forward to practice. The temperature was usually above a hundred degrees, and the three large lakes nearby pushed humidity levels high. It felt like a swamp inside that helmet and uniform.

In my childhood most experts agreed that drinking water during games and scrimmages was not good for you. One afternoon a linebacker was so parched he could hardly speak when the coach asked him something. There had been a thundershower earlier in the day, and a mud puddle had formed near the sideline. After hearing the linebacker’s arid voice, the coach asked, “You thirsty, son?”

“Yeah, Coach,” the boy replied.

Pointing at the mud puddle, the coach jokingly said, “Go get yourself a drink then.”

The boy ran over, dropped to his hands and knees, and drank, earning himself the nickname “Mudwater.”

Why more kids didn’t die back then is a mystery to me. Or maybe they did, but the deaths weren’t reported the way they are today. Our only respite was when we pleaded to use the bathroom and then drank from the sinks, which spewed lukewarm water. For the ultimate refreshment we might sneak a sip from the drinking fountain in the hall when Coach wasn’t looking.

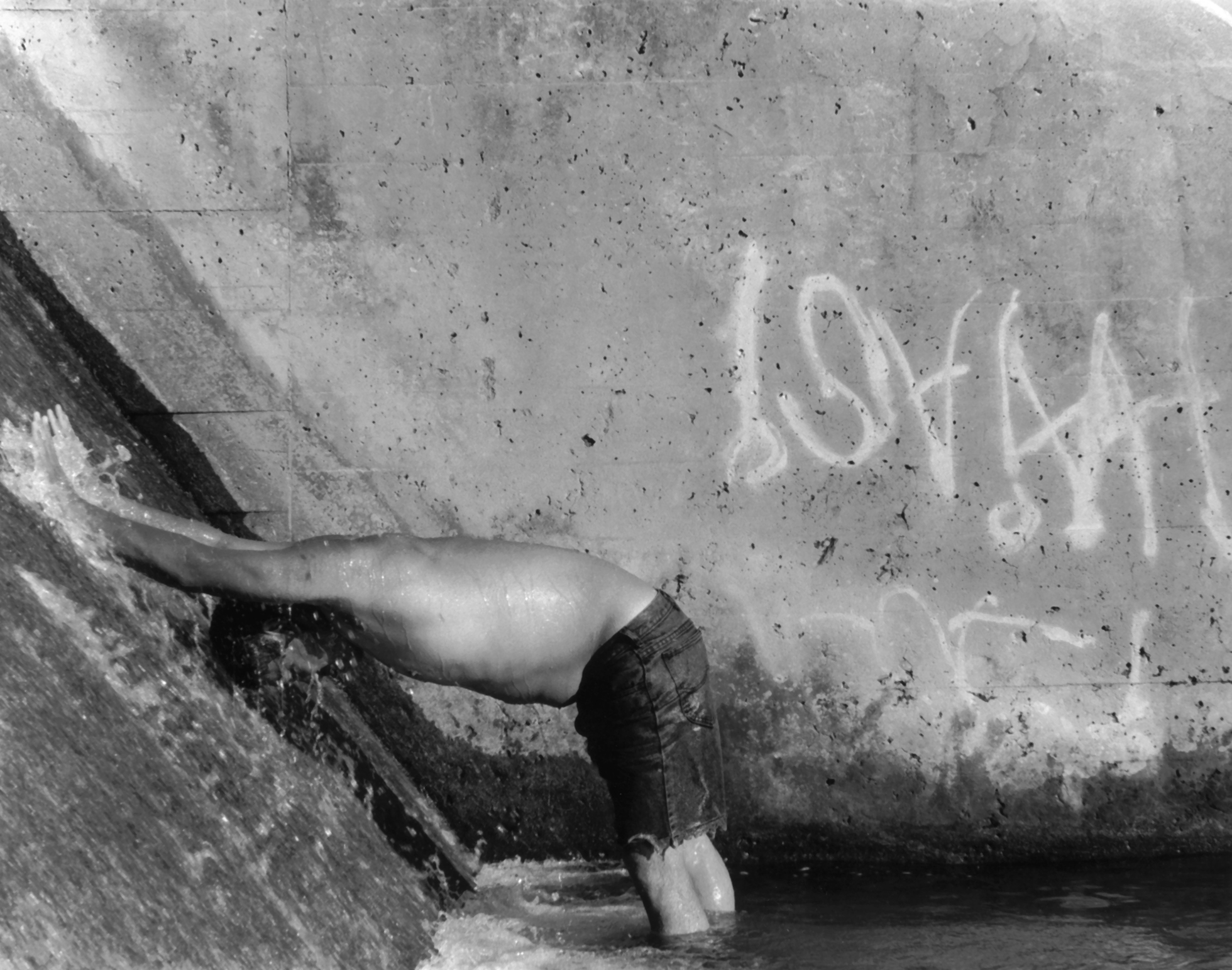

Our locker room was in an old concrete-block gymnasium: no air conditioning, stuffy as hell. When practice was over, we shunned the showers, opting instead for a speedy change into summer clothing and a quick, windows-down ride to the swimming hole on the Little Mazarn. A rope swing dangled from a big cottonwood tree there, and all other worldly pleasures paled in comparison to releasing that rope and being immersed in the spring-nourished creek. We’d spend a good hour swimming, dunking each other, and sharing the occasional slug of contraband beer.

On one occasion, when the thermometer registered 105, we wallowed like hogs in a mudhole by the bank, coating ourselves from head to toe. A photograph remains of us standing there, smiling in mud-covered camaraderie.

Pat Conover

Albany, New York

Many years ago, on a frigid night during the Christmas holidays, I went out with some friends in our small Montana town. We met at a bar for drinks while my husband was home with the kids.

As we were catching up, my high-school sweetheart entered through the front door. I hadn’t seen him in several years. He took off his heavy wool coat, shook the snow from it, and brushed flakes out of his hair. When he saw me, his face turned serious for a moment. Then he smiled and walked to our table.

In high school our relationship had been off and on. We’d never gone all the way, but we couldn’t get enough of each other’s lips, hands, whispers, and caresses. The old longing came rushing up and caught me completely off guard.

He greeted everyone else at the table but didn’t look at me. Finally he came to my end, sat down, and asked where my husband was. I asked where his wife was. When it was clear that neither spouse would be joining us, he said it could be a dangerous night.

It turned out his brother’s band was playing at the bar, and he had come out to watch. Over the course of the evening I tried to act nonchalant while inside I was buzzing, alert to exactly where he was at all times. He asked a couple of my friends to dance but not me. I became angry and remembered that part of the reason we had broken up was because I’d gotten tired of his games.

Finally the band started to play “Feel Like Makin’ Love,” and he took my hand and asked if I’d join him on the dance floor. He pulled me close; I pulled him closer. Every place our bodies touched pulsed with heat. He whispered in my ear, telling me how good I felt, how beautiful I was, how much he wanted me. Having been told by my husband that I was frigid, I was shocked by the intensity of my desire. I practically moaned with lust.

My old boyfriend tried to convince me to leave with him. I told him I couldn’t because of my kids, and because I knew that, if I did, I could never go back to my old life. He thought differently: if we gave ourselves this one night, he said, we could return to our spouses better off.

After the music had stopped, he took me back to my chair, kissed my hand, and whispered that he’d wait in his truck for ten minutes, in case I changed my mind. He said that no matter what I decided, it had been good to see me and hold me again. Then he left.

It was a long, cold drive home alone that night.

Name Withheld

I went to elementary school in a small town in northern China. In the wintertime the fifty or so children in my class huddled around a coal stove in the middle of the room, still wearing our thick jackets, hats, and gloves. Taking our hands out of the gloves to write was such misery that for the first lesson of the day, before the stove heated up, we’d recite poems from memory or do math in our heads. During ten-minute breaks we would go out to the yard to jog, jump rope, or chase each other to get our blood moving.

Sitting close together to feel the precious heat gave us more opportunity to whisper gossip, pass illicit notes, and tickle each other. Placed on the stove, a bowl of water became a humidifier; orange peels, a natural air freshener. Most of us brought our lunch to school in aluminum or enamel containers; late in the morning we would stack them on top of the stove to heat our food.

By then the room was warm enough that we could take off our jackets. The winter sun melted the frost on the window and projected a rainbow on my open book. Through the waves of heat above the stove the teacher’s face became distorted like one of van Gogh’s paintings.

A few years later I would move to an entirely different country, where central furnaces, twenty-four-hour hot water, and even heated car seats are taken for granted.

Anna Hui

San Francisco, California

In the jungle’s dry season the sun beat down on us through the denuded trees, and we needed to drink at least a gallon of water a day. Two would have been better. We never got enough.

Every soldier carried his water in a combination of canteens. If all mine were full, I had enough for three, maybe four days. I carried my main supply in a fragile five-quart bladder inside my rucksack to protect it. At every rest break I checked it for leaks. When I found one, I patched it with the sticky tape from the bottom of a smoke grenade. Replacement bladders were hard to come by.

Whenever the platoon stopped, we put down our heavy rucksacks with a groan of relief and formed a quick perimeter. After we’d tended to security, the first thing I did was take a drink of water — not the large gulp I wanted but a mouthful, maybe two. In moments of weakness, three or four. It was warm and tasted of water-purification chemicals.

When I had patches of infection on my arms from scratches, a field surgeon urged me to wash them three times a day with antibacterial soap. I handed the soap back; there was no water to spare for this luxury. Making coffee was the only purpose water was put to other than drinking, and it could be argued that coffee — even C-ration mud — was a necessity.

Once, while pushing to secure a hilltop for some nameless firebase, we had to go two days past our normal resupply date. Our supplies were nearly out: no food, few smokes, and less than a quart of water apiece. The platoon moved in slow motion. Twice we stopped to tend to a grunt who had collapsed from the strain, expending precious water to cool him until he could continue. That night we spread two ponchos close to the ground, hoping to catch any rain that fell or even enough dew to give everyone a cool mouthful. We were disappointed.

Finally the resupply bird came with water. It hovered some sixty feet up, just above the tops of the trees, but wouldn’t land. The crew chief and gunner pushed bladder sacks of water out the open doors. Most were torn open by the sharp branches. Enough survived to fill a canteen for each man, no more.

Not enough, never enough.

Ron Orem

Owings Mills, Maryland

I was fourteen and in the middle of the growth spurt that would deliver me at long last to a respectable height when my granddad decided I was big enough to work a summer job on his pipeline-construction crew. He was the hard-drinking patriarch of our clan, and his approval meant everything to me.

I showed up for my first day wearing boots, Levi’s, and a blue work shirt, the same as the older laborers, only mine were shiny and new. The work was hard — swinging a shovel or a pick to clear ditches that had been shoddily dug by a backhoe. At home I had always regarded the old man as generous, since he occasionally treated my little brother and me to steaks and was known for picking up the tab in bars, even for strangers. But at work I saw a different side of him: penny-pinching and mean in small ways.

When I got my first paycheck, I saw that he’d paid me a dollar an hour for my labor in the hot sun — a tenth of what his other workers were paid, thanks to their union contract. But I cashed my check and kept quiet, glad to at least have some spending money.

That summer I not only grew four inches but also put on twenty pounds of muscle from all the hard labor. In the fall my football coaches would be shocked by my transformation, and I would go from being a hapless fifth-stringer on the freshman team to a starting guard for the junior-varsity squad.

On my final day of work all that was left was to seal the ditch forever with asphalt. This task had to be finished before we could leave, because the steamrollers were expensive and Granddad had a permit to block the street for only one day.

It turned out to be the hottest day of the summer, 112 degrees in the shade, and we were most definitely not in the shade. The asphalt was delivered at 325 degrees and had to be shoveled rapidly into wheelbarrows and then spread evenly over the ditch before it cooled. We started before dawn and finished late that evening as the sky was growing dark. I was proud that I had worked as hard as any of the men and never taken more than a ten-minute break to gulp ice water from the metal cooler.

Usually stingy with praise, Granddad actually put a hand on my sweaty shoulder and said, “You done good today, son.” I flushed with pride. When we got home, he gave me my check for my fourteen-hour day in the blistering sun: eight dollars. He hadn’t even paid me for the extra hours I’d worked, let alone given me the double time the other workers had received.

I swallowed my disappointment but later confessed it to my grandmother. She was sympathetic and said my granddad would make it up to me.

He never did. A few weeks later my grandfather died suddenly of a heart attack.

The resentment I felt over that paycheck has lived on in me. I always long to trust, yet struggle against, the men who hold power over me. Whenever I find myself in a position of authority over another, I am compelled to be generous, as if to balance the injustice I experienced on that hot summer day almost half a century ago.

John Edward Ruark

Portola Valley, California

I was home for a brief visit in the humid heat of a Carolina summer. “So, you really don’t believe in God?” my dad asked nonchalantly as we drove by the church of my childhood.

Oh, Lord, I thought. I always felt a slight rush of blood to my cheeks when this subject came up.

I’d been raised Catholic — with the incantations and the incense, the gilded chalice and the guilty conscience — but I’d pulled away from the Church as a young woman, finally rejecting all religion. My dad was a devout convert, and I couldn’t help but feel that my lack of faith caused him consternation.

Still, I was honest with him. I said I thought that there are energies and dimensions we don’t understand, but I didn’t think there’s a deity, certainly not one who sits in judgment and punishes and rewards.

“So, you don’t believe in an afterlife either?” he asked. “No heaven and hell?”

I told him I believed that we have only this one life to live, and when it’s over, it’s over. I didn’t acknowledge that I sometimes had late-night moments of existential dread and panic due to this belief.

“Who knows, Dad,” I said, wanting to lighten the mood. “I could be wrong. Maybe after I die I will be pleasantly surprised.”

“Or maybe not,” he replied.

At first I felt shock: had he implied that I’d be banished to the fires of hell? But then I saw the twinkle in his eye.

My father died a few years later. I still don’t think I will see him in an afterlife, but I have felt his presence near me since his death.

I am a Buddhist now. I wonder if he would consider that an improvement over my atheism. I certainly do. I’ll take the cycle of rebirth over the fires of hell any day. And my meditation practice has quelled those white-hot fears in the middle of the night.

Katherine Hamilton

Camarillo, California

When we first moved into the housing co-op, our two young children shared one bedroom while my wife and I shared the other. Then my mother-in-law came to live with us. Her name was Gertrude, and she slept on our sofa in the living room. Space was tight, but heat was part of our co-op maintenance fee, so we were never cold. In fact, sometimes we would have to crack the windows at night to let some cool air in.

As the kids got older, the co-op apartment became too small, so we bought an older house a few blocks away. There was more room, but the utilities were now all ours to pay.

The cast-iron radiators were inefficient and the windows drafty. Cold winds whistled through the cracks around the doors. Even with a new, energy-efficient boiler, our gas bill began to soar. I mandated that the thermostats be set at sixty-eight and not a degree more. My wife and children complained that the house was too cold, so I gave them all wool sweaters and flannel pajamas for Christmas.

Sometimes I would find a thermostat set at seventy-six degrees. Of course no one would admit to changing it. I bolted a cover over the control, and my wife brought home some infrared space heaters, which glowed so hot our children wanted to roast marshmallows over them. Seated near one, I felt as if I were sunbathing on a beach. The gas bill went down, but the electric bill went up.

Through it all Gertrude never complained. She would just sit by the nearest heater or radiator with her sewing or a book on her lap. Why couldn’t the others follow her example?

One day I came home early from work and found Gertrude in the living room with her hands wedged into a radiator. Looking up at me like a child caught in the act, she said that sometimes her hands ached, and when she held them to the radiator, the pain went away.

I had never looked closely at her hands before, but now I saw they were red and swollen from arthritis, knuckles twice their normal size, the skin raw from the dry winter air.

I realized that she’d been the one turning up the heat — not in defiance of me but in search of some relief. She looked so small and helpless that I felt guilty about the way I’d been treating everyone. In my effort to save money, I’d been ignoring their comfort. When my wife and kids had protested, I’d just dug in, determined to prove them wrong.

I promised myself I would listen more and let the others participate in family decisions. I stopped checking the thermostats and made certain that my mother-in-law always had a heater beside her.

Robert G. Essick

New Rochelle, New York

When I was seven years old, my mother decided to get over her fear of dogs by breeding them. She bought Sassy, a certified Pembroke Welsh corgi with a full pedigree flown over from England. We were not allowed to let Sassy outside to greet the black-and-white mutt who always wandered by. My mother had chosen a special mate for her. I was disappointed when the exciting part happened while I was at school.

When I was a teenager, however, and the dogs were in heat, my older sister and I would invite our friends over to watch. Seven of us leaned against the fence in our backyard one day to observe a tri-colored stud having his way with our corgi Lena. The four boys in the group laughed and shouted catcalls, but I was quiet, my eyes darting to the left every few seconds to look at my sister’s friend Jason — his straight white teeth and the little crinkles under his eyes when he laughed. I gripped the fence with both hands to settle the stirring in my loins. Lena looked almost bored while the stud pounded against her from behind, but my own heart beat loudly, as if keeping time.

Sindee Ernst

Owings Mills, Maryland

My boyfriend remembers the heat of his Hawaiian childhood as if it were a lover who got away. Just the thought of that golden place of eternal summer makes him heave a sentimental sigh.

In his restless youth he moved several times to the West Coast, but he would soon pack his belongings and make the long trip home again. Now he’s having another go of it in Portland, Oregon, where we met.

The seasons here are unfamiliar to him. He’s never gone to a pumpkin patch on Halloween or worn a scarf at Christmas. He needs to be reminded what month the leaves turn and when the crops are ready to harvest. Every day he checks the weather forecast, longing for that cartoon sun to break the monotony of clouds and raindrops. When spring comes, he wants to swim outdoors, and I’m reluctant to tell him that all the rivers here are fed by melting mountain snow.

Everyone in Portland complains about the weather, but one word from my boyfriend about it and I find myself defending the rain and the cold. I insist that winter offers us a time to rest, with blankets and fires and huddling close for warmth. When the sun does finally come, people positively burst with activity; not a moment is wasted indoors.

I make the seasons here sound like the right and natural order of things. How can he call it “paradise” to sweat all year round? To live where everyone drifts drowsily about in the heat and every day is the same?

I can feel my arguments fall flat. Most of the time my boyfriend seems happy, but as winter approaches, I can’t help but wonder if he’ll go back to Hawaii, and if he does, will he sigh sentimentally when he remembers me?

Chelsea Schuyler

Portland, Oregon

I grew up in a small town in Michigan, where spring and fall were fleeting but summer seemed to last forever. The days were hot and humid, and sometimes it was hard to sleep in our un-air-conditioned house. I remember being escorted home once from a date to find my entire family sprawled on the floor in the living room — the only room with a window unit.

My five siblings and I had to entertain ourselves during summer vacation. Mom used to send us outside to play and then lock the door so we couldn’t get back in. We tried everything to get her to open that door.

“Mom, I’m thirsty!”

“I have to go to the bathroom.”

“I think I’m going to throw up!”

“Please, Mom. There’s bees out here!”

“I just saw a snake!”

Nothing worked. She always made us use the bathroom before we went outside, and the snakes were all nonpoisonous.

Once, my sister was stung eight times by a wasp that had flown into the armhole of her romper. She got to go inside and have baking soda and cold cream applied to the stings. I was jealous.

I remember the sound of cicadas buzzing, the smell of vegetables being steamed right in the garden, the prickly feel of the dry grass on our bare feet, the way the sand and straw from the barn would stick to our skin. (But it was cooler in that barn.)

I remember being allowed to bring a blanket from the house so that we could lie on the grass under the big pine tree in the front yard. We made a tent with the blanket and front-porch chairs and nearly suffocated inside it.

And I remember Mom telling us that if we’d be good and not fight, Dad would take us to the lake when he got home from work.

Now I live in North Carolina. The heat here from June through August is brutal. There are still cicadas and snakes — including some poisonous ones — but they don’t bother me, because I rarely go outside, other than to dash from my air-conditioned house to my air-conditioned car.

Kate Fischer

Greensboro, North Carolina

“I’m on my way,” he phoned to say, in a bedroom voice. Minutes later he appeared at the door with his hands deep in the pockets of a nylon team jacket.

This was before anyone knew about us.

He came inside bearing kisses as light as butterfly wings and hugs so warm they would melt chocolate. In the half-light of gray dawn I led him down the hall to my room and pulled him into my bed.

It was a rainy Sunday. The sheets were crisp. I remember the downy hair on his belly, how, when my hand paused there, his back flattened against the mattress and his chin rose toward the ceiling.

His embraces were like a bonfire, and I was kindling. Every time we met, I burned a little hotter. We held each other, his lips on my neck, his breath in my ear, but we never removed our clothes, because we were still committed on paper to people who had abandoned us long ago.

I remember the longing in his eyes each time we parted. I wondered how we would survive another week without touching. And when we were together, I wondered how we managed to contain so much heat.

Juli O.

Columbus, Ohio

I was at the local New Year’s Eve celebration when I gazed across the gymnasium and saw my housemate, a look of horror and heartbreak on her face. She was screaming, “The house burned down! Hurry! Come with me!”

Riding home in her car, all I could think about was Tucker, my cat, who was my closest friend. Had he been inside or outside when I’d left that day?

As we neared home, a sea of red lights flashed against the glistening ice and snow. The old Victorian was still standing but almost completely gutted, and the firefighters were mopping up. I attempted to run inside to find Tucker, but men wearing gas masks blocked my way. It took several of them to restrain me in my hysterical, grief-stricken state.

Finally the fire inspector agreed to take me inside. We had five minutes.

The downstairs was completely destroyed. The porcelain bathroom fixtures had melted. We found the second story only barely spared, the paint on the walls blistered by the extreme heat. I called out for Tucker, but he was nowhere to be found. The inspector theorized that my cat had escaped when the firefighters had opened the door at the bottom of the stairs. Then he gently placed his hand on my arm and said it was time to go.

I could not bear not knowing what had happened to Tucker. Each night after work I went back to the skeletal house to search for him. Yellow tape draped around it declared, DANGER — FIRE LINE — DO NOT CROSS. I would bring a blanket from the motel room where I was staying and wrap myself in it to stay warm while I whistled and called in a singsong voice, “Tuhhh-kerrrr!” My calls always gave way to sobbing and finally wailing. I was learning how to grieve.

After several weeks of this I had a dream about Tucker. He was curled up on his “doctoring towel,” a threadbare bath towel that I always used when he needed medical care. As I got closer, I saw that he was missing teeth, his fur was dry and bare in spots, and he was skin and bones.

When I awoke from the dream in the middle of the night, I got dressed and returned to the house with even greater resolve. I had to know the fate of my old friend, good or bad. I whistled for him and heard a sound like a cat: plaintive, small-voiced, coming from someplace high up and to my left.

I saw a quivering, feline silhouette on the roof of the garage next door. One of my neighbors, who knew my story, heard me outside and brought a ladder and a bag of cat food. I carefully climbed the ladder with a handful of the food. As I reached the top, I could see him huddled at the bottom edge of the roof: Tucker! He had all his fur and his limbs, but he was incredibly skinny and clearly terrified.

It had been twenty-five days since the fire, and the ground was covered with ice and snow. Where had he been all that time? He came close enough to lick one of my fingers and take a bite or two of cat food, then ran out of my reach. Eventually he curled up in my arms. He was so slight I was afraid of hurting him.

I took him to the emergency veterinary hospital, where the night-shift staff all came to look at the cat who’d survived a fire and almost a month in the cold.

The vet examined Tucker and gave him fluids for dehydration. The pads of his feet were covered in delicate pink skin, which the vet said meant that they’d been badly burned by the fire. We were lucky there’d been snow on the ground to cool his burns. The vet reckoned that the night I found Tucker might have been the first time that he’d been able to put any pressure on that new, tender skin. I imagined Tucker holed up somewhere, waiting for his feet to heal enough for him to be able to walk again.

Lauren Silver

Indianola, Washington

The air conditioner is not working, but I light two candles and sit in meditation anyway, as I do every day.

I have been a Zen Buddhist for almost twenty years, and yet, every time I sit, it is not so much a deep, spiritual experience as it is a time of scattershot thoughts and frustrations. I think of what I need to buy and the chores I have to do; of the guy who cut me off in traffic and the sexy actress I saw in a movie last night.

Today droplets of sweat are trickling down my back and chest, reminding me of my time in prison.

I was an inmate when I took my Zen Buddhist vows with my friend Doc. We sat in meditation every day on the yard, in the late-afternoon heat. There were about a hundred other inmates out there, some playing softball or basketball, others walking or jogging on the path. It was a noisy setting for our practice. And yet we sat and meditated as mindfully as we could.

The worst for me was the heat and the insects. A trail of sweat ran down my back like the Mississippi. Ants crawled over my legs and feet while I anticipated the first bite. Gnats landed on my sweat-slick face and tried to climb into my eyes. I was miserable.

One day Doc told me about a Zen student who struggled with the temperature and took his question to the roshi. The master replied, “If you are hot, be a hot Buddha. If you are cold, be a cold Buddha.”

I remember that now and relax. I have meditated under worse circumstances. Doc is still meditating on the inside. I think of him, and my frustrations disappear.

David Wood

St. Petersburg, Florida

I was seventeen and riding my 1956 Vespa scooter from Berkeley to Crystal Crag Lodge in Mammoth Lakes, California. I’d gotten a summer job at the lodge, cleaning cabins during the day and washing dishes at night. The pay was a hundred dollars a month, plus room and board — pretty good for a high-school kid in 1963. I’d already worked part of the summer, but I missed my scooter, so early on a Saturday I’d hitchhiked back to Berkeley to get it. My boss had approved my plan, but she’d told me that if I wasn’t cleaning cabins by 8 AM Monday morning, I’d be fired.

Somewhere outside Modesto the Vespa’s engine quit on me. After three hours, a lot of pushing, and several stops at service stations where mechanics failed to diagnose the problem, an old-timer at a lawn-mower shop replaced a cracked spark plug and charged me $1.80, and around 6 PM I was back on the road.

By eight I was riding at a crawl up the western side of the Sierras into Yosemite National Park. In addition to my unplanned three-hour delay, I’d failed to account for the reduction in speed as a three-horsepower scooter maneuvered up a series of steep switchbacks. My sweat shirt was little help when the temperature quickly dropped below freezing due to the altitude. Then my dim headlight, which barely lit the twisting roadway, began to blink off and on, leaving me to either brake or drive on blindly for several seconds at a time.

I was prepared to stop at any sign of human habitation and ask for help, but there was nothing but a wall of dark pines on both sides of the roadway — when I could see them.

Sometime after midnight I pulled over to look for shelter in the woods. My legs numb from the cold, I crawled into the trees, wedged myself under an overhanging boulder, wrapped my body in a poncho, and fell into a sleep of exhaustion.

I awoke several times during the night, reasonably certain I was going to freeze to death and occasionally delusional, most apparently so when I saw a large bear shamble out of the dark and settle in next to me with a sighing grunt, sharing with me its considerable animal warmth. The hallucination was so vivid that I could smell the pungent odor of its wet, matted fur and hear the sound of its breathing as it rolled its back against me and pushed me farther under the boulder. Grateful for the heat of its body and the protection from the wind, I slept soundly.

When I woke, the light was just hitting the top of the steep mountain slope. I waited until the sun reached a flat boulder about two hundred yards away, then stumbled to the rock and stretched out atop it in the radiant warmth.

By nine that morning I’d reached the lodge and was back at work cleaning a cabin. When my boss found me, she displayed uncharacteristic kindness by not firing me, but she did tell me to go shower and change clothes. “You look like hell,” she said. “And you smell like wet fur.”

Tom Selsor

Stoughton, Wisconsin