June

June is a song I don’t really know the words to but am singing along with anyway. One verse tells of small yellow warblers calling, Witchity-witchity-witch, and garishly plumed western tanagers up from Mexico to feast on just-hatched salmon flies crawling drowsily through bankside willows. There’s a verse about a young bull moose, too, modest antlers still in velvet, chewing cress by the river road each day, and something about a black bear dragging a trash bag through the preschool parking lot. In another verse the mountain sky dumps barrels of snow so heavy the green branches snap, and in the next the sun comes out to shine on wet asphalt that glitters so brightly you have to pull your truck over beside a high meadow, from which a meadowlark sings: I am the god of summer resurrected, come to salvage your soul from the snows.

If only there were a chorus to help slow the song down and allow me to ponder a few lines. But there is no chorus.

I spend each June guiding tourists down Montana’s rivers, alternately basking in June’s glories and mourning its swift passage. Busy is not quite the right word. Think April 14, H&R Block. If I believe my journal, which contains only four entries in the past five years between Memorial Day and July Fourth, June doesn’t exist, a strange missing stratum from the sedimentary cross section of my life. How do these longest days of the year become the briefest? I was mulling over this conundrum the other day after I lost an oar to the river.

I had anchored my boat on an inside bend of the snowmelt-fed Rock Creek. Whoever christened that body of water a “creek” had clearly never attempted to cross it in June, when the burly current threatens to unfoot the knee-deep wader. We — my clients Peter and Miller and I — had devoured a snack of salamis, grilled steaks, and cheeses, all washed down with a bottle of cold white wine while waiting for the freckled sunlight to warm the water. Large stoneflies, their dark wings sponging up the sun, began to pour from the alders and congregate in the air above the river to mate. Occasionally one of the biplane-like insects would crash into another, the pair sputtering to the water’s surface, where they’d be swept away and possibly devoured by a trout.

I pulled up anchor, took hold of the oars, and with vigor shoved them simultaneously into the U-shaped oarlocks. The port oar settled in perfectly, but somehow the starboard oar slid clean over the lock, shooting into the ankle-deep shallows. Jumping over the gunwale, I waded in after it. For twenty yards or so the oar seemed within reach, just a stride or two beyond me. I splashed through the water as if chasing a dropped dollar bill blown along a windy sidewalk. Downstream an island divvied the river into two channels: a slower, shallow channel that fed into a backwater, and the deeper main channel that straightened over boulders into a small rapid. The oar, of course, veered right, doubled its speed, and rode along the island’s cutbank. Peter later said I looked like a rodeo clown running from a bull as I high-stepped along the bank, leaping junipers, a downed barbed-wire fence, clumps of sage, and beaver-whittled willows, still hoping to catch the oar. Finally I drew even with it and stabbed my hand into the water, but the oar caught a chute and sped off into the glare.

I put my hands on my knees and, panting, looked back at Peter and Miller, who were doubled over in laughter. I could have vomited, literally. Though I had a spare, I hated to see the oar go. I stood winded alongside the horizontal rush of the snow-fed river we call a “creek,” thinking about what had been lost to it.

July

Mary and I and our son, Luca, take a lot of creek baths in July: sleep late, wake up, lounge around the house while it’s still cool, then pack a picnic and walk the few blocks down to the creek bed. It’s a tedious scramble across the dry cobbles caked in stale moss and stonefly exoskeletons, and I always exhale in relief when I spread the quilt at the spot where the creek eddies behind two La-Z-Boy-sized boulders. We call this place the “Sweet Spot” because, during the feverishly hot weeks preceding Luca’s birth, Mary would lug her pregnant body here and sit nearly submerged for hours, reclining against the rocks that December’s ice jams had arranged like living-room furniture.

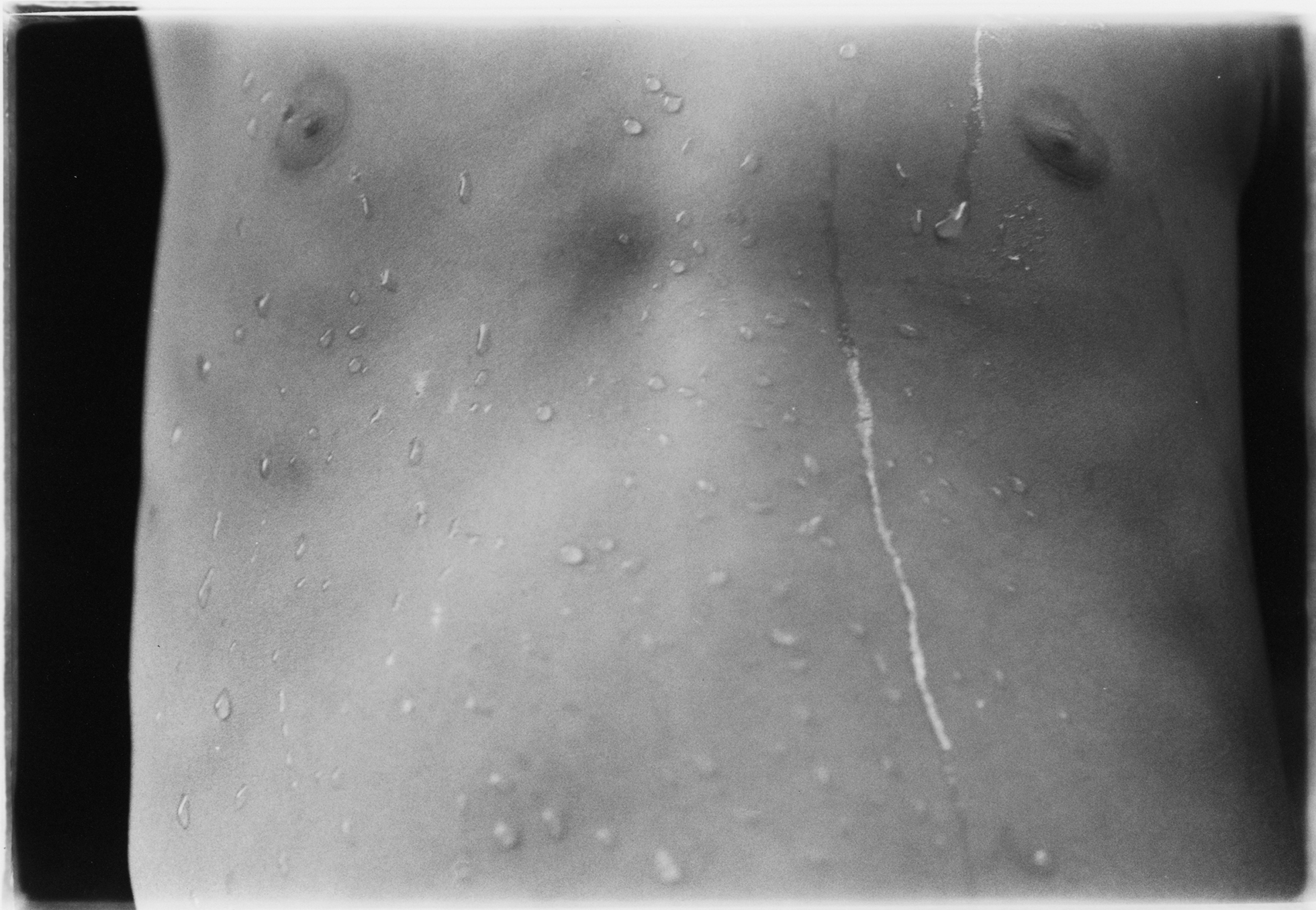

The body is happy here: warmed by the improbably high sun falling through cottonwood boughs and the vague heat radiating from dark granite, then cooled by a plunge in the downhill rush of water. Though Luca splashes around naked, the Sweet Spot’s a bit too close to a well-traveled trail for us adults to take off our clothes. The other day, though, while chasing a garter snake through a swath of forget-me-nots, I saw, not fifty yards downstream, a slender blonde remove her light blue bikini and slip into the creek.

I had left my prescription sunglasses on our quilt, but, squinting, I could blurrily see her swim to the surface, look squarely at me, and wave. Trying to look like the most diligent of snake hunters, I sucked in my gut and waved back. I admit, had a genie spontaneously appeared and offered me just one wish, I would have asked not for a million dollars but for my glasses. The utter wonder of a woman’s body.

She got out and stood in the sunlit corridor, drying off in the breeze, her back to me. Then, after sliding on her bikini bottom and tying the top in back, she lay down on a spit of sand and lifted a book to her face.

Have I said the suit was the color of a forget-me-not’s stamen?

Shaken, I turned upstream and submersed myself in the current, imagining my mind as a log the creek might hollow out, but when I surfaced, the image of her standing there stood firm. Above the water stoneflies undulated, the veins of their translucent wings making the space around me appear charged with energy, as if some invisible beings of the air had become momentarily visible. I touched my abdomen, where a faint burning resided. Then I stumbled barefoot back to our creekside picnic.

Luca looked up from his pile of skipping rocks: “Did you catch me a snake, Daddy?”

“No, love, I did not.”

“Awwww.”

Mary came to my rescue: “If Daddy can’t catch ’em, nobody can.” Then she said to me, “You were searching pretty hard.”

I felt a little liquor headed. “Yeah, well, there was a girl down there. Skinny-dipping.”

“Really,” Mary said, clearly ready for the punch line. “Did you talk to her or just peek at her through the bushes?”

“I waved.”

“Well? Was she pretty?”

I picked up my glasses from a sage-colored square of quilt. “I reckon she was.”

Never was there a woman less prone to jealousy than Mary, but by now she was intrigued. “Since I have to pee,” she said, “perhaps I’ll have a look.”

Mary ambled out of sight around the bend as the boy fired stones across the water. Without looking away from the rippling he’d caused, he held out his hand: Reload, please. I passed him a skipper from the pile and watched the pockmarks on the creek’s surface expand and slide downstream.

When Mary returned, a smirk puckered her face.

“You are a funny man,” she said.

“What?”

“There was no girl down there, but you had me going.”

“Hold on,” I said.

I slipped into the creek and swam down to the beach where the woman had stood after her dip, but there were no footprints, no imprint of a slender body, just the tracks of a killdeer that stopped abruptly at the waterline.

After the sun had gone down, with the boy bathed and sleeping soundly in his bed, Mary and I sat eating chips and homemade guacamole on the quilt, now spread over the backyard’s prickly, unsprinklered grass. I still carried in my abdomen — and was trying to articulate to Mary — the sensation that I had swallowed some incredibly potent shot of vodka whose burn wouldn’t recede or weaken.

“I bet you saw a sylph,” she said.

“A sylph?”

“A fairy sort of thing. Frail, erotic. Go Google sylph and see what pops up.”

I hated to enter the kiln-hot house, especially to Google something, but I was curious. I fired up the computer and typed into the search engine, “Sylph”: invisible beings of the air; frail cloud creatures who carry with them a fecundity that is sometimes passed on to the humans they come in contact with; sexually provocative winged rulers of the dreaming. Through the window I glimpsed Mary’s shoulder and felt a tremor of stomach nerves as intense as any since middle school. The body, the sylph seemed to be saying, if she was real, if she was still with me. Remain in the body.

August

Today I awoke to the sound of wind in the pear tree, fall’s first hard fruits hanging unpicked from the jostling limbs.

Stepping out of bed, I saw Mary’s black dress on the floor, the black dress I’d zipped her into and out of the night before. We’d dined at a fine local bistro: a salad of prawns and arugula, a cool green gazpacho, then a chimichurri rib steak. Mary drank a glass of sauvignon blanc, and I spruced up my soda water with a little mandarin vodka I’d smuggled into the restaurant via flask. Afterward, walking across town, I led Mary away from our car, and when she asked what I was doing, I told her I simply wanted to keep walking with her, to be seen in her presence, to raise my status, perchance, the way some B-grade-sitcom actor might if photographed with a bona fide Hollywood diva. Then home to the bed: holiest, most sensual of havens.

Yet I awoke this morning as aware of my mortality as of the wind in the pear tree. I thought simply: I will die. And before that, barring some scientific miracle, I will grow limp and incapable and will want to recall again this fabulous memory of her body moving beneath my hands.

Day dawned cool, and Mary and I sipped tea at the kitchen table, enjoying the rarity of a morning alone. Then came the sound of the boy’s bare, scampering feet on the hardwoods. He often looks surprised to see us in the morning, as if his nighttime dream journeys have been so vast he can’t believe we’re actually still here in the house, right where he left us.

“I had two bad dreams and twenty-thirty good,” he said.

“What were the good dreams about?” I asked.

“Dragons.”

“And what were the bad dreams about?”

“Dragons.”

We learned that his baby sitter had sung him “Puff the Magic Dragon” before bed, and after breakfast Mary dialed up the seventies Puff the Magic Dragon cartoon on YouTube. Luca seemed to be watching it contentedly as Mary and I went on sipping tea. Out of the corner of my eye, though, I saw his smile morph into a wince, and then a grimace, and before I could ask what was the matter, he began to sob uncontrollably.

It took about half an hour of Mary’s patient soothing before we could decipher how the video had set him off. Luca gathered himself, dried his tears with the back of his hand, and explained: “It said little boys don’t live forever.”

Mary and I looked at each other, cocking our heads like two dogs puzzled at their owner’s action. Then we simultaneously recalled the lyric: “A dragon lives forever, but not so little boys.” We tried to explain that the line was a metaphor for growing up, but our own little boy would have none of it.

“When we die,” Luca said, sniffling, “do our faces change?” and he launched into another torrent of sobs. After he’d calmed down a bit, he told me: “I wanna go in my crib.”

“Sweetheart,” I said, “you don’t have a crib anymore. We gave it away when you grew out of it,” which set him wailing again.

I knew from the start as a parent that I would be privy to life at its most raw, but I hadn’t known I’d be witness to the Fall itself, my son’s realization of Time, the actual end of his innocence.

Midafternoon, after Luca’s nap — and after he had, as only a child can, thoroughly cast off his worry — he and I drove up Mill Creek several miles to fish for native cutthroat trout. When we reached the first hole, I cast into the glare-coated water and watched the lure pause on a cushion of current before the trout plucked it from the surface. I caught a small cutthroat with dark bars in its scales — an indication that it was still a parr and too young to go to sea. Luca asked me to let the palm-sized, parr-marked fish go. Little parr-marked boy, wild and pure.

Carrying a stick he called his “cutlass,” Luca held my hand and hopped across the rocks, singing, “Yo, ho, ho, pirates on the go!” Soon we found a suitable boulder some glacier had set in place eons ago and sat watching the ripples our sandaled feet made on the water. In addition to the cutthroat, we’d caught a mess of nonnative brook trout, which I kept for the pan. I was thinking of how I might poach them in butter, a little fresh sage, and white wine when Luca poked me in the side with his stick and startled me from my reverie.

I picked up my own stick and turned to him in mock combat. “Prepare to walk the plank, landlubber!”

“No, no, these aren’t swords anymore,” he said. “They’re oars, and this is our boat.”

I would prefer to see the world as the world and not some elaborate metaphor. And yet when I recall “rowing” with Luca today, I remember my lost oar — a mere shaped stick floating down the fleet waters of Rock Creek in June — and I can’t help but think, OK, I get it. The river is time.

If the river is time, then what does my lost oar represent? A moment? An image? A memory? Perhaps a moment that becomes an image that becomes a memory?

Right now, two months since it evaded my outstretched hand, the oar could be lodged in a root wad three hundred yards downstream from where I dropped it, the current eating at the grain of the wood. Or it could easily have ridden the length of Rock Creek and slipped into the Clark Fork of the Columbia River and continued through the EPA Superfund site of Milltown Reservoir, slowing a bit in the largely stagnant water before tumbling over the century-old dam. For all I know the oar could have shot past Missoula and surfed the rapids of two gorges on its way to the teethlike turbines of Bonneville Dam. Today, 787 miles downstream, some boy on the beach at Astoria could be using a piece of the chewed-up blade to smooth down a sand sculpture.

Wherever it is, the current has set to pulverizing it, much the way that time pulverizes a moment. A quantum physicist would assert that the notion of a “moment” is an illusion; that life, which seems so fractured, is actually one long moment to which one’s mind attends only at certain points. Yet what about those instances to which we hold fast, the remembered moments we grip tightly, like oars, without which we would be unable to withstand the fleeting nature of existence?

One summer when Luca was eight months old we camped on an island on the Big Hole River. Before sunrise I sat with him on my lap so that Mary, who’d been up off and on all night to feed Luca, could sleep. The river rushed around the island, slammed hard into a sandstone cliff wall, then caromed into an audible riffle that charged through a short box canyon. Overhead the wheeling, hurtling stars seemed to make a similar rushing sound: groan of the turning world, blood pulse of the universe. Around us and above us, all was movement, all was in flux, while on the island I held my sleeping son and believed we were not moving, that the world had halted its passing for us.

Of course, by then, the moment itself had passed, elusive as a stray oar carried by the snow-fed currents.