James, after receiving your letter (so old-fashioned!) at my place of employment, I muddled through my last class of the week, faked a stomach bug, and went home early to my flat to pour a tall, murky glass of the communal drink of the natives, which, yes, is also the private daily restorative of your old man, if you so choose to think of me that way. To be honest, I’ve had to summon some courage before writing you. Specifically I leaned out the casement window of my living room (it’s the kind that opens on hinges, like a door) to take in the lovable slapdashery of my neighborhood: The granite cobblestones. The vine-covered canopies. The motor scooters parked at a lilt. The warm fragrance of the afternoon’s bread baking. The tin-man stovepipes and their little hats. The grimy facade of the adjacent apartment building. The ironmonger’s clanging hammer. The snap of checkers on the backgammon boards. A tanker moving through the Bosphorus Strait must make sixteen turns, cutting them as tight as it can; every half hour one slips by so close that it looks, from my vantage point, as if it’s passing up the middle of the coast road. In fact, I can hear, what with my windows open, the low rumble of a churning propeller now.

Well, I seem to be getting carried away. What I want to say is: Ah, spring. . . . Can any task be unpleasant in spring? A herring gull has just landed on a neighboring roof, so close I can see the yellow in its hard little eye. Did you know that in your neck of the woods this bird is an endangered species, while in mine it’s an obnoxious pest? This seems to me as apt a metaphor as any of the unbridgeable chasm between our two worlds. And yet, here we are.

First let me say that I’m delighted to hear from you. Again, how you found my workplace address is notably absent from your letter. Perhaps through your mother’s efforts? Or otherwise on the sly, using all the online resources with which your generation is so proficient? Even here, on the brick-and-mortar back stoop of Europe, I see this technological prowess in many of my students, who aren’t that much older than you.

Speaking of age: you are now eleven, as indicated on the back of the Little League card you sent me. Thank you for that. Yes, you’ve got that bat cocked like you know what you’re doing. Bear in mind, though, how many children want to be baseball players. The competition will be stiff; I would suggest you explore something more esoteric but with no less a payoff. What that would be, I don’t know. You’ll have to discover it for yourself. Nonetheless, thank you for the baseball card. It’s very cute.

Little League . . . Now, those are two words I haven’t heard in years. Here it’s nothing but futbol, as they call it. People bet on it, riot over it, kill over it! The refugee children play with anything they can get their hands on — soda cans, taped-up lumps of clothing, lemons, bottle caps, cat skulls, et cetera. Just the other day, on Independence Avenue, where it seems only Arab tourists shop these days, I saw a pair of private-school brats ball up a half-eaten sandwich in tinfoil and kick it back and forth before offering it to a begrimed little girl who knelt in the middle of the street, blowing through a plastic recorder. She peeled open the foil, sniffed the sandwich, and then, to my horror, finished it off.

But that’s how it is, James. There are those with wealth and those with a tinfoil ball of soggy bread. As for me, I’m in neither category. We have here a “healthy middle class,” as The Economist likes to put it, of which I am one cog among the many gears of the sprawling institution of privatized education. I should say that even the foreign teachers like me are not, by American standards, very well-off. My monthly salary isn’t paid in dollars, so with every one of the prime minister’s idiotic public remarks — that citizens with dollar accounts, for instance, are traitors and/or terrorists — the real value of my paycheck pitches downward by another quarter percent. Believe it or not, I make less than I did when I arrived here ten years ago. There’s no point in being coy about figures: I get about two thousand dollars a month, which I can only hope is less than what your mother makes, whatever it is she’s doing these days. Now that I know your address, I suppose I could send you an occasional gift, albeit with a caveat: the post here is notoriously unreliable. What I can most assuredly offer you, however, is a bit of fatherly advice.

Judging by your grades, which you’ve so proudly enumerated in your letter, it’s clear that you are a hardworking student. Your penmanship is shockingly adequate for a child’s, all your t’s crossed, your i’s dotted, your g’s and j’s dangling below the line at the same casual angle, like the bare legs of a group of boys lounging on a dock. They have a saying here that I would translate — I do some translation, by the way, and am hoping to make a career out of it — as “Don’t invent anything; just study.” That, of course, is nonsense. Grades are not the be-all and end-all. Good grades only get you into college, which wins you a place at the table of adult mediocrity.

You’ve written me quite a few questions, James, but I have one of my own: Have you noticed yet how most adults spend the first hour of their day slouched at the breakfast table, chin in palm? It’s not that they’re tired. Rather, psychologically speaking, they are most vulnerable in the morning. Torn by the alarm clock from their dreams, they must face the next eighteen hours yoked to some banal label like “administrator” or “credit officer,” and they wrap their fingers around the toothbrush, the bureau knobs, the teakettle handle as if clutching at the last shreds of their happiness. Try this: Ask any of your teachers what their Plan A was; then ask what letter they’re on at this point in their lives. F? K? Z? Ask your mother, too; I’m sure she’ll tell you, “A.”

I was around your age when I first noticed this phenomenon — I’ll call it “silent adult dysphoria” — in my own parents. They never truly despaired over anything, nor did they lose their heads with joy. As I observed them, I realized they existed for three purposes: to raise me, to make food, and to maintain the plain-but-solid midcentury character of the house so that it could be sold for a profit at a later date. They were also involved in a church, which I’ll explain later, but I suspected that this odd and relatively brief venture into religion was a distraction from their real lives, which stretched into the future with little novelty or purpose. I don’t suppose you’ve ever met them, have you?

My Plan A? It was the tuba. And I began to get good at the tuba for the same reason any eleven-year-old decides to get good at anything: I’d discovered the Happy Vertex. I remember sitting at the dinner table with my parents one night in September when my father turned from my mother and said to me, seemingly apropos of nothing, “At least, that’s what the Dutch say.” Seeing that I hadn’t been following their conversation — with all their opaque references and strange digressions, what child could? — he repeated what I’d missed: “Too soon old, too late smart.” He raised his eyebrows at me, resuming his meal, and I did something I’d never done before: I asked him what he meant. Why then? Who knows, but I asked! For a moment it seemed, from the wrinkles that suddenly appeared under his eyes, that he doubted the sincerity of my question. But then his eyes softened, and he attempted an explanation — a not altogether immediately illuminating one, but substantive enough to give me something to think over that night in bed.

Indeed, I couldn’t sleep. For a long time I stared at the dozen or so glow-in-the-dark stars I’d stuck to the ceiling in a stupid, crowded cluster, that pithy proverb revolving carousel-like in my head, until a thought occurred to me: Why hadn’t I spread them out? Those ridiculous stars, they were the work of a child, a child who wasn’t yet intelligent enough — or, at the very least, thoughtful enough — to create realistic constellations. How could I have been so simpleminded? What a shame I hadn’t gotten those plastic stars in my stocking the following Christmas, when I’d have known better. I’d have asked for more and turned my room into a veritable galaxy. And that was when I understood my father’s throwaway comment, which I’m sure by that point he’d completely forgotten. And at that moment, James, I felt a genuine concern for my own future, and I suddenly recognized the potential learning power of my own preadolescent body and mind.

Let me explain:

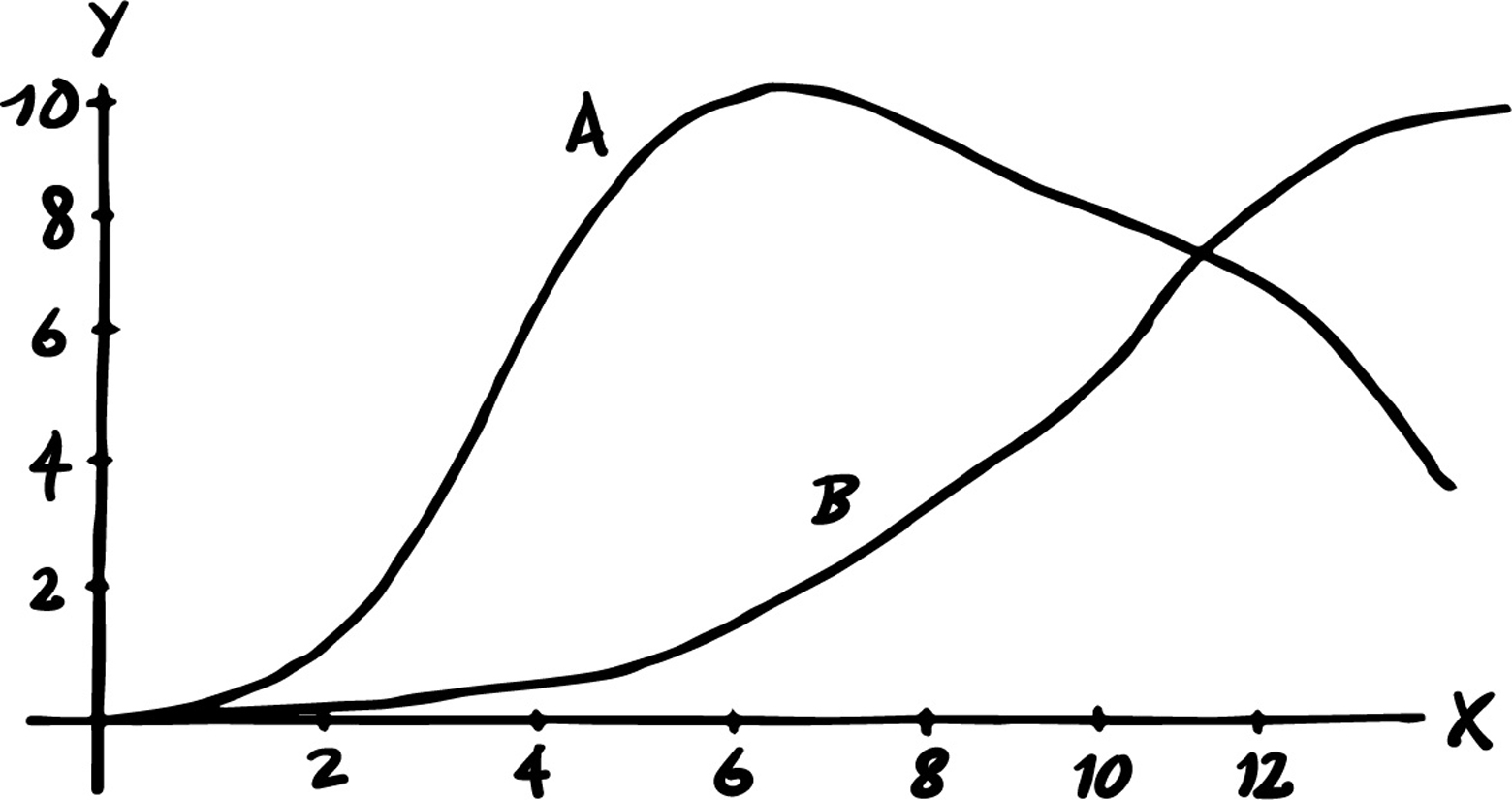

You do graphs in the sixth grade, don’t you? Well, imagine a graph where the X-axis represents age, from birth to twelve, we’ll say, and the Y-axis something like, I don’t know, “capacity” (arbitrarily quantified from zero to ten). Then imagine two lines setting off from the origin and following an upward slope. Line A rises sharply at first, as it depicts the capacity for talent with the possibility of mastery. I’m thinking here of three-year-olds on hockey skates, or five-year-olds at the Bryant Park chess-boards. Line B, however, which delineates self-awareness or self-determination, really doesn’t take off until around ten years of age. And if those two lines intersect, they will do so at around eleven. Hence: the Happy Vertex. Does that make sense?

I’ll draw it for you:

You see that the cruelty of the Happy Vertex is its fleeting nature. Line A plunges downward, line B eventually plateaus, and before you know it, the distractions take over, and you’re thinking about girls, or you take a brief but intense interest in Mazda Miatas. Soon you’ll think about money, nothing but money. And, I should further warn you, for many children the Happy Vertex passes completely unnoticed.

Of course, as a child, I didn’t conceive of this in the schematic way I’m explaining it now. It was all intuitive.

I sat up in bed, hugged my knees, and immediately started planning. But rather than start afresh with some athletic or scientific endeavor, I decided to throw all my energy into something I already enjoyed, which was the tuba. Because I’d been at it for only a month — I’d started in the sixth grade rather than fourth, which back then was when most schoolchildren took up an instrument (is this still the case?) — time was of the essence.

The next day at school, lunch followed band, and while my classmates clamored into the hallway, I stayed behind. Mr. Blum had returned to his desk and was already absorbed in a small pile of papers. With his head down, he waved away two or three lingering students and their questions as if swatting at flies, telling them, “Tomorrow, tomorrow, we’ll talk about it tomorrow,” which was always his refrain. (He sounded like Macbeth.) Once they’d all left, he lifted his head to see me standing across the room beside the metal storage lockers. He winced at my presence and asked what I wanted. I told him that what I wanted was to be one of the best tuba players in the world.

“A tubist,” he said. “You want to be a tubist.”

Mr. Blum was actually rather young, no older than I currently am, now that I think about it. A quintessential woodwind man — slight in stature, sharp-nosed, high forehead topped with a wisp of thinning hair — he took a less-than-active interest in the brass section. Nevertheless I thought I noticed in his expression a willingness, perhaps even an eagerness, to take me under his wing. But then he turned in his swivel chair to the window and looked out at the line of cars beneath the trees for a long time, so long that I began to wonder if he was waiting for me to leave. When he finally spoke, he seemed to have woken up from some sort of reverie. “Next week,” he told me. “Let’s talk about it at your lesson next week. In the meantime? Just keep those cheeks puffed and anchor the corners of your mouth.” He patted me on the shoulder, walked me toward the door, and stared at me a moment. “You do have a natural sense of rhythm,” he said, and he nudged me into the hall.

His was an awkward, confusing response, and I doubt now if he was at all aware of the influence his words had on me. They acted as a bellows, stoking my ambition. A similar thing happened to a colleague of mine, who remembered her swimming teacher telling her, when she was a girl, that her backstroke was excellent, leaving my colleague struck by the conviction that she was going to the Olympics. As for me, I came home that afternoon, ate a snack, and went straight up to my room. For six hours, breaking only for dinner, I practiced the two-octave chromatic fingering chart Mr. Blum had handed out to the brass section at the beginning of the year. I remember little of what my parents said that first night — which, yes, felt like (and I’d never feel this way again) the first night of the rest of my life. I suppose my mother would have made some pampering remark while my father remained silent. Later he probably rolled his eyes to the ceiling beams overhead — his desk was directly beneath my bedroom — and turned up the volume of the tax tapes he listened to in the evenings, to better serve his financial-planning clients.

Within three days I began to sound good — at least, to my own ears. I followed the same daily schedule — come home, eat a snack, go to my room, and practice until nine, breaking only for dinner — and was soon working my way up and down Mr. Blum’s handwritten sheet of scales with ever-increasing speed. I did this with quarter notes on Wednesday and Thursday, eighth notes on Friday and Saturday. On Sunday, at a loss for what to do next, I took out the score for “Colonel Bogey” and played it twenty, maybe thirty times, until I knew my part by heart. I remember my mother looking in that afternoon, her otherwise long face wide and bright with surprise. The rims of her eyes glistened. I asked her to sign my practice chart, which showed forty-two hours. “My word,” she said. “I can imagine the look on Mr. Blum’s face when he sees this.” Later that night my father barged in, mumbling and blinking uncontrollably. He squinted at me as if I were some strange boy who’d snuck into his home and replaced his son. Then he smoothed his mustache with the palm of his hand and told me I sounded very good, but could I please pack it in for the night? He was trying to finish one last tape before bed. I gripped my tuba in my lap, afraid he’d haul it away, but he stalked off without another word.

What could he have said? I believe he regarded my newfound mania with distant caution. Young people burn with passion, James. To an adult we’re like a barely contained fire: get too close, and we’ll melt away the wax-thin illusions without which adults simply cannot live. Besides, one thing was clear to him: his son had fallen in love with music. And music — more than literature, or painting, or athletics — is the purest expression of human genius. It resonates with the most oafish of people, as exhibited by my father’s submissive reaction. Against music one is defenseless, and when I breathed life into those eighteen feet of twisting brass tubes, animating the notes in the exact manner in which the great F.J. Ricketts had collected and organized them, I felt tethered somehow to all the other musicians and composers who’d preceded him — Sousa and Tchaikovsky, Beethoven and Mozart — such that each of us was pressing a kind of communal string to the fretboard, sounding our voices up and down fifteen hundred years of musical history.

The following Monday morning I had my weekly tuba lesson with Mr. Blum. Stopping short at his door, I saw him through the little square window, sitting at his desk with his head down, pencil in hand. The windows behind him stretched from the metal radiator cabinet to the ceiling; he could turn around and see, beyond the football field, the distant red-brick high school where his wife performed the same duties as him. I realized that he was probably working on a score. Whenever I think of him now, I see in my mind a young Mahler, what with those thin glasses and billowing shirt sleeves, that wisp of hair splashed over his forehead. When we sat down, he plucked my practice chart from my folder. “Forty-two hours?” he said. “Is this a joke?” He accused me of forging my mother’s signature and stood so fast, his chair jostled one of the snare drums behind him, sending a pair of sticks clattering to the floor. But before he could leave to call my mother, I launched into my one-octave scales with a steady train of quarter notes, regular as a pump jack. Mr. Blum returned to his seat beside me. I doubled up to eighth notes. He tapped the shelf of the music stand with his baton and stopped only when he saw I was losing my breath. I had yet to build up any stamina, but otherwise I’d executed this little performance flawlessly. “That’s very good,” he said. “Quite good. What about the Ricketts?” And without taking the score from my folder, I closed my eyes and played “Colonel Bogey” from start to finish. The final note drained into the silence. I lowered my tuba. Some muted shouts reached us — a group of high-school boys galloping around the track outside. Mr. Blum went to his filing cabinet and took out a book. Plopping it on the music stand, he explained it was a collection of advanced tuba exercises of significant difficulty, and he spent the rest of the lesson tapping me through Wagner’s “The Giant.” When the bell rang, he slipped the book into my band folder. “Learn half of this by January,” he said, explaining that his wife had a tubist in the high-school band, but he was terrible. She needed a good one for the spring concert; they were doing “Circus Polka.” Was I familiar with it? I shook my head, and he scribbled on an index card a list of music he thought I ought to purchase: Mahler’s First, Petrushka, Pictures at an Exhibition. He said he’d give me the score to “Circus Polka” the following week, and he saw me through the door with both hands on my shoulders, either pushing me out or leaning on me for support — I don’t know which. I couldn’t see his face, but I felt as if his delicate hands were all that kept me from floating to the ceiling.

This was thirty years ago. Strange as it may sound, the present moment might be the first in which I ever acknowledged the distance between the man I am now and the boy I was then. Fifteen or twenty years is one thing, but thirty is something else altogether — a generation! I should thank you, James. Your letter has caused me to look back at this time through a sharper lens, and, to be honest, I find myself speculating a little as to the sincerity of Mr. Blum’s initial encouragement. Specifically I wonder if, like my father, he’d tossed away that compliment about my ear for tempo for want of anything else to say and with little regard for its effect. But I’d be interested in knowing what you think. You seem mature enough to make a judgment on the matter.

Anyway, I told my parents what had happened in my lesson that week, and, being parents, they were pleased, albeit to a mild degree. You see, it’s common knowledge that when a child pursues a hobby with such maniacal passion, nine times out of ten he flames out phoenix-like before rising again from the ashes with some new fixation. As a teacher I’ve seen this happen to many children, over and over, until there’s nothing left for them to burn for except love. I believe this is what my parents expected. They would let the fever, as it were, run its course.

Over the next two months I cloistered myself in my bedroom, working through that book of advanced exercises. So that my grades wouldn’t dip, I made good use of my one study hall and counted my lunch and gym periods as sufficient time to maintain a cordial relationship with my friends. On the weekends I hoarded my time from my parents, joining them downstairs only to eat. After lunch I would see my mother leave for the grocery store, and hours later, without having moved from the vantage point of my window-side chair, I’d watch her return. Meanwhile I’d hear my father raking the yard or putting in the storm windows or clearing the gutters with a broom handle. And when my mother had put away the groceries, organized her coupons, and started dinner, and my father, freshly showered, had set himself up again at his desk with his tax tapes, I’d still be there in my chair by the window, practicing away. Some nights I’d lie in bed, propped up by pillows, playing from memory until I’d fall asleep with my tuba cradled like a lover in my arms.

I ’m glad today is Friday. It’s getting late, and I still haven’t finished your letter, which is turning out to be a very long one indeed. The clock has just struck nine, the lights of the neighborhood lampposts are all on, and I can hear one of the carpenters at the bottom floor of my building winding back the shop awning. If the previous two nights are any indication, at midnight the Orthodox church around the corner will give its bell a good five-minute ring — for what purpose, I do not know.

Ah, you’ve asked me so many questions, James. I hope I’m answering some of them, in my strange way. I have plenty of my own, too, one of which is prompted by my reference to the church bells above.

I remember, after the many consular visits and the long-sought-after green card they produced, that, when I brought your mother to the U.S., she so effortlessly adapted to the various cultural facets of American life: The weekly outings to the hollow-columned strip malls. The impassioned discourse on food. The obsession with that filthy, anthropomorphized creature, the family dog. My point is that she always had a kind of fluidity of character. So it wouldn’t surprise me if she has converted to the Protestant faith, bought herself a Kentucky Derby hat, and joined one of those megachurches that talk about God as if he were a vending machine.

It was on a weeknight in November, two months after I began practicing my tuba in earnest, that my life took yet another strange turn. We — that is, my parents and I — were assembled at the dinner table when my father said to me, “I hope you don’t have any plans on Sunday.” Of course I did. Had he not noticed the cetacean melodies pulsing through the floor every weekend?

“Why?” I asked.

“What’s it matter why?” my mother said.

He just came out with it: “Because we’re going to church.”

Now, I had no objection to religion. I didn’t think in those sorts of terms, nor have I ever opposed churchgoing in principle — although it did baffle me to see my parents suddenly lift their noses from the grindstone, from the dishes and the tax tapes, and point their gazes heavenward. No, my objection had everything to do with time, of which my father apparently thought I had plenty. But rather than fight him over it, I went silent for a few days and wrote a letter of protest. I remember explaining that I saw life as if it were made up of slivers, like slices of a cake. You extract as many slivers as you can for yourself, and they quickly add up. Those lost Sunday slivers just might make the difference for me between greatness and mediocrity. I expected my parents would tell me that forgoing practice once a week wouldn’t matter in that false endgame adults like to call “the grand scheme of things,” which I knew wasn’t true. So I wrote that Mozart’s father had been his first teacher, that Yo-Yo Ma had settled on playing the cello at the age of four, and that I was already far behind them. (The Happy Vertex occurs much earlier in the prodigy.) I added up the slivers of hours I’d lose: six, maybe seven each week, which made an annual total of fifteen twenty-four-hour days.

I watched as my father read my letter, and I respectfully asked him to consider the level of tax expertise he might gain if he spent an extra hour a day listening to his tapes. But he waved away my objections.

Let me pause to make a brief point here: There is something wildly suspicious about a middle-aged man claiming to have suddenly found religion. Never trust his intentions; they’re buried so deep that he himself is unaware.

So off we went to church, James. To church! Literally over the river and through the woods, half an hour away. I learned in the car that one of my father’s colleagues had invited him, and I expected the place to be as perfunctory as a bank. How wrong I was! This was no kneel-and-stand affair; no quaint, green-shuttered New England chapel. The place was housed in a converted four-bay auto garage along a strip of county road, and the service stretched well into the afternoon. The music lasted an hour, the sermon another, and the “altar call” a half hour at least. Even the coffee hour afterward lasted fully as long as its name implied. By the time we got home, it was past two, and I still had my homework to finish.

I whined bitterly on that first ride home, but we returned to church the following Sunday, and the Sunday after that, and church soon became a part of the weekend routine, along with my mother’s grocery shopping and my father’s gutter cleaning. I got nothing out of the experience except inescapable boredom. I should remind you, James, these were the days before not only the smartphone but the Internet as we know it. (My God, what a thought. It’s like imagining the entirety of the Americas on the eve of Columbus’s landing.) The mind was forced to seek distraction in the real world, which for me was the church bulletin or the handsome brown maps at the back of my mother’s Bible. But once the music began and the congregation stood to sing, there was nothing I could do but grudgingly join in. Sometimes I’d stare at the felt banners of crosses and doves hanging on the walls; other times I picked at a mysterious burn mark in the hymnal rack or counted the number of motor-oil stains on the concrete floor. But these distractions lost what little charm they held once I found something genuinely alluring up there on that makeshift stage: the girl — or, rather, the slender young woman — at the keyboard, leading us in song.

Her name, I learned, was Andrea, and she must have been at least eight years older than I, her skin very pale, her eyes a wintry blue. She kept her long black hair gelled to a curl, a style that has never attracted me since. In fact, I have yet to fall in love with another woman of Italian descent. Isn’t that strange? I imagined that the worship band behind her had been assembled not for the Lord’s benefit but for her accompaniment alone — including the choir of a half dozen middle-aged ladies, perched on a small set of risers like hens on a roost. And because it was she who led us in song, I had an excuse to gaze. Occasionally her eyes flicked up to catch me staring. Once, she smiled — privy, I was sure, to my secret longing. There was a childless couple who sat in front of my parents and me, and I positioned myself to see between them so I could follow undetected the fluid movements of Andrea’s body. She became the only reason I stopped complaining about attending church. She had somehow stormed the beachhead of my boredom and begun a slow campaign for the conquest of my thoughts.

One Sunday before service, as I sat with my elbow on my knee, reading the church bulletin for perhaps the third time, she sat down in the pew in front of me, turned, and said, “I heard you play the tuba.” I thought she meant that she’d heard me play the tuba, and she laughed and said, “No, no. I mean, I know that you play the tuba.” Then, as casually as if she were asking me about the weather, she said, “How would you like to be my tuba player?” She propped her elbows on the back of the pew, narrowing the gap between us. Her face inches from mine, she shrugged her shoulders up beneath her ears. I sat there waiting for an answer to spring to mind. I suppose it must have been the innocent use of that possessive pronoun that had fused my mouth shut. Her tuba player. I turned to my mother.

“The girl’s asking you a question,” she said. “What do you say?”

And as I framed my response, James, not a thought went to the Happy Vertex. Instead I summoned all the courage I had within me to explain that I didn’t have my tuba with me, but could I play next week? Of course, she said; she didn’t think I carried my tuba around with me everywhere. I’d have to come to rehearsals, though; they were Thursday nights. Did I mind? I shook my head, and with that I lost not one but two days of practice a week.

My mother drove me to rehearsals and waited in the foyer outside the pastor’s office with a book. Andrea set me up with a chair and a music stand beside the drummer, a thick-limbed divorcé with Coke-bottle glasses who’d recently found a job as a corrections officer in a downstate prison. I remember this because he would mention it repeatedly, as though he couldn’t believe his own good fortune, and it depressed me to no end that a man in possession of a bona fide musical talent would be so happy to have found such a job. At first I wondered what his marriage had been like and how poor they must have been. Where had he gone wrong? Where had they all gone wrong?

Although I was overjoyed to be in Andrea’s presence, I was also aware of the losses resulting from my decision to join the church band, which I tried to mitigate by incorporating into the worship music some of the advances I’d made in my practice sessions at home. But the tuba can do little more with cathedral tunes than pump out that incessant ostinato, unless I soloed, which I was encouraged to do from time to time. Besides, with Andrea there, playing with any significant concentration was like trying to thread a needle on horseback. And so I held the line, oompahing away the hours every Thursday night and Sunday morning.

But, as I said, James, I was happy. I harbored no regrets. You’ll laugh at this, but I sensed that I wasn’t so much trying to thread a needle as I was weaving with my tuba the first gossamer fibers of a love knot. What else could explain why, when Andrea looked over her shoulder at the rhythm section to signal the final chorus of a hymn, her eyes would rest on mine; or how, when I’d pepper a verse with some little sixteenth-note flare, she would smile at me and — I couldn’t believe it the first time she did so — wink. When my mother took me home, I would look out the window at the windswept fields of moonlit corn stubble, and my heart would nearly burst. School awaited me in the morning. I couldn’t bear the thought of returning to that world of neglected homework, regulated lunches, clanging lockers, and the sloppy execution of “Colonel Bogey.” No, not when I had a beautiful adult sharing a bit of her affections with me. I tried to stay true to my craft. That cluster of glow-in-the-dark stars served as a reminder. Mr. Blum noted the reduction in my practice hours, although without reprimand. He appeared satisfied with my progress, but — how can I put this in a way you’ll understand? — a worm had crept into my thoughts and begun to eat away at everything but Andrea. Unable to focus on practicing at home, I would put my tuba down; lean forward, chin in hand; and grant myself a little flight of fancy about her. Other times I closed my practice book and played “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” because it reminded me of her. And then, one Saturday in mid-December, I put in two hours, called it a day, and went downstairs to watch TV. I didn’t practice my tuba again for the next week.

And there it is, the double high-pitched ding of the church bell, echoing throughout the midnight streets. I need to wrap this up.

You’ve asked me about my job. As I said, I am a teacher. As for my hobbies, I translate, take little trips, and eat interesting foods. That is all I can afford to do, although I have a colleague who makes a killing off of private math lessons. I admit that I get a little jealous whenever he trades his “old” car for something new. But that’s one of the surest signs that you’ve missed the Happy Vertex: an automobile fixation. Now, me, I have little need. The metro system grows like ivy, and if I want to get out of the city for a few days, I can find a well-priced five-star bus staffed by stewards who serve tea, coffee, and cakes. No, a car would be useless to me. Aesthetically speaking, however, I have a great fondness for the Mazda Miata. That is because Andrea drove one: a red convertible coupe. She would park it in front of the church’s double glass doors, which the morning sun would strike at an angle so that, upon entering the sanctuary on a Sunday, the last thing I’d see of the secular world was that car’s bright and solid reflection.

It wasn’t until I’d attended the first Thursday rehearsal that I realized Andrea was the owner of that Miata. After she pulled in just ahead of my mother and me, I watched her get out, lock the door, and push back her sunglasses, which she must have worn out of vanity, as the sun had already set. There was a hint of the devil in that car, and I quickly came to love the curving stretch of its hood, the short porch of its rear, the headlights that looked like bedroom eyes. Every man has his beau ideal, James. He settles on it in childhood and installs it on that proverbial pedestal, where it remains for the rest of his life. You may have assumed mine to be the lilting cadences of some great nineteenth-century score, but, no, it is that cliché of clichés: an attractive woman behind the wheel of a red sports car.

Despite our time spent rehearsing together, Andrea and I hadn’t once spoken alone. Nonetheless I had the impression that I could, simply by talking to her, insinuate myself into her favor. If Andrea could only hear me speak and see how I listened to her words, without any other adults in the room to overshadow my already diminutive stature, she might see a man in me yet.

One night in December, while we all milled about onstage waiting for a few latecomers, I felt so comforted by the Christmas season — the sanctuary was bedecked with green bundles of pine branches, and the slats in the walls of the Nativity manger glowed with an orange light — that I made a passing remark to Andrea regarding her Miata. I believe I said, “I like your car.”

“You want to take a ride in it?” she replied.

I was so taken aback that I responded with the sort of underenthused “OK” young boys barely manage to get past their lips when in a state of elated disbelief. Off she went into the foyer to speak with my mother while I took out my tuba and began to warm up. When she returned to her keyboard, she traipsed her fingers over the keys and announced to me, in a low voice through her microphone, that she would be taking me home. One of the choir hens giggled. The percussionist dashed off a drum fill: biddle-de-boop — splash! I may have been in the sixth grade, but the playfulness of her comment wasn’t lost on me.

My mother went home. Goodbye, Mother. After rehearsal had ended and everyone else had left, I turned out the lights, save for the one in the manger, while Andrea closed up. I followed her outside into the cold, where the gravel crunched under our feet. When we got into her car, her Miata, the space between us was no wider than a hand span, unlike the immense cavern of my mother’s Voyager. Andrea clipped her seat belt and tossed her hair over her shoulder. She put the car in gear — it was an automatic — and off we went. A little ways down the road, she squirted the windshield with wiper fluid. The blade on my side was worn, leaving the glass a streaky blur.

We rode in silence, past the reedy pond and up a hill toward a lone traffic light in the distance. No doubt I had lobbed my thoughts several miles down the road. I suppose it was in response to my reticence that Andrea suddenly asked if I wanted to ride with the top down.

“Won’t it be cold?” I asked.

“I’ll blast the heater,” she replied, swinging the car onto the shoulder. She opened the pair of latches over the windshield. The long day had softened the gel in her black hair, and as she leaned over me, it brushed my nostrils. Down went our two windows. The cold swept her fragrance away. She snapped the canvas top behind us, and we were off again, speeding beneath a dark canopy of leafless branches silhouetted against the moonlit sky. I can tell you, James, that the heating unit of an early-nineties Miata is pitifully inadequate, despite the proximity of one’s hands to the vents.

The cold seemed to make Andrea talkative. She spoke about her Miata and how it had come into her possession, and of her ambitions as a vocalist and the various people who had thus far helped her get her “tenterhooks” into the meat of her career, which she helped me visualize by taking her hands off the wheel and miming a pair of upturned claws. I told her that I knew exactly what she meant. “Oh, do you?” she replied. I said I did, what with my tuba and all. “That’s right,” she said, as if she’d forgotten. “You’re very good, you know.” Then she returned to her previous topic — herself and her voice. She said she had to be careful because she could never be sure what, exactly, people were interested in: her voice or her looks. She asked if I knew about that sort of thing, and I couldn’t take it anymore. I swallowed my childish inhibitions and boldly asked if she was teasing me. “Oh, I’m not teasing you,” she said. “You’re very gifted — you’ll have to watch out.”

She continued to talk — about what, I haven’t the slightest memory. The freezing wind spilled over the top of the windshield, churning inside the car like an eddy, blowing our hair forward instead of back. The moon shifted with the turns in the road. I felt simultaneously elated and miserable, and I fell silent until we pulled into the driveway at my house and she asked me to help her put the top back up. Andrea never offered to drive me home again.

The holidays passed. Snow soon covered the ground. I forced myself to finish Mr. Blum’s exercise book, joined the high-school band, and performed “Circus Polka” in the spring — which would be, I’m sad to say, the high-water mark of my music career. Practice had simply become such a slog that, as I stared out the window at the neighbors’ snow-covered field, I felt like I was schlepping my tuba across an interminable distance. Bored, distracted, I wrote songs to Andrea, most of which were in common meter, so that whenever I played a hymn, my own words ran through my mind.

About a year later she married a man from Tulsa and moved out there, God have mercy, with her Miata. Another year passed, during which our church troupe was led by our drummer-cum-prison-guard. Then, shortly before the summer between the eighth and ninth grade, when an adolescent boy either tragically or brilliantly attempts to reinvent himself, Mr. Blum mentioned in front of everyone that if I wanted a tuba to practice on for the summer, I’d have to put in a request to his wife. The breezy, indifferent manner in which he said this, while casually flipping through his score, incensed me. Nor did I appreciate the idiotic notion that his best musician had to go through some sort of protocol in order to secure an instrument. Out of protest I made no such request. I ended up missing the tuba that summer much less than I’d expected, and I never bothered to sign up for the high-school band. Mrs. Blum called me to her office at one point, and I gave her an excuse about focusing on my studies for a year. Around that time, my father grew bored with church, and we stopped going.

In the back of my mind, James, I figured I might one day return to the tuba, but I never did, except once, in my final year of high school. I had a small part in the school play, and because Mrs. Blum’s band room was just across from the auditorium, the cast used it as a dressing room. One night, as I changed out of my pilgrim’s doublet and cloak, I saw that someone had left a tuba out. To impress my friends, I hefted it into my arms and gave “Circus Polka” a try. A low, moist, offensive flutter bubbled forth, and my friends doubled over. Caught up in the performative moment, I did a little jig and, with a percussive series of flatulent puffs, earned more cheap laughs. It was depressing. I had essentially confronted the complete loss of my artistry, and in anger I fetched an apple from the refreshments table and dropped it down the bell.

How had I reached that point, James? You could say I’d lost interest, and that may be true, but where’s the causality? For a long time I’d fixated my ire on Andrea. Specifically I’d wondered if she hadn’t infected me with a kind of inertia. Had she declared outright the absurdity of my love for her, I might have sought refuge in music. And, in the less likely scenario that she had given voice to her feelings for me (because it isn’t that rare that an adult develops a kind of amorous interest in an adolescent), I might have kept playing out of inspiration and joy. But that patronizing flirtation and those vague compliments — and at such a delicate time! — what’s a boy to make of it? Still, as I sit here considering the dullness of my professional life and the ever-dimming excitement of living as a stranger in a strange land, I don’t think so much about Andrea as I do about the rest of the adults. Do you understand? The child with his misplaced affections or the promising student who curries his teacher’s interest, only to lose it for no fault of his own — they’re no different from the doting kitten that kneads its owner’s lap and ends up tossed to the floor. Oh, the damage they do with their proverbs and clichés, their opaque soliloquies, their sudden tenderness, their unfounded frosty aloofness. . . . Oh, the damage they do, the damage they do!