Actor Peter Coyote suggested we meet for this interview at his home north of San Francisco. Nicknamed “the Treehouse,” it has a striking view of Mount Tamalpais and is close to Golden Gate National Recreation Area and San Francisco Zen Center’s Green Gulch Farm. It is a long way from Hollywood, where Coyote has worked since 1980, appearing in more than ninety films and television programs. He says that he is “a Zen Buddhist student first, an actor second.” He will be ordained as a Zen priest in August.

Coyote has had an eclectic life, having done everything from farming to being a stockbroker. A self-described “socialist radical hippie anarchist environmentalist,” he’s seldom without an opinion on an issue and never one to hold back his views. Born Rachmil Pinchus Ben Mosha Cohon in New York City in 1941, Coyote took his stage name from an experience he had while taking peyote in the Southwest. He has been socially and politically engaged since the age of fourteen, when he volunteered for the Adlai Stevenson presidential campaign in Englewood, New Jersey. Coyote’s passion for progressive reform continued at Grinnell College in Iowa, where, during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, he helped organize a group of twelve students to travel to Washington, D.C., and protest nuclear testing. They fasted for three days outside the White House before President John F. Kennedy invited them in to talk with National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy.

After college Coyote joined the San Francisco Mime Troupe, a guerrilla street-theater group still in existence today. He and some of his fellows from the mime troupe went on to form the Diggers, an anarchist group that “acted out” its ideas of what culture should be, questioning the core values of capitalism and distributing free food to runaways in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, sometimes feeding hundreds of people a day. They also ran a Free Store, a Free Clinic, and even (briefly) a Free Bank. The Diggers evolved into the Free Family, a network of communes around the country pursuing an alternative economy and culture.

Coyote is the author of the memoir Sleeping Where I Fall: A Chronicle, a portion of which won a Pushcart Prize. A new book, about what he calls the “present mass hypnosis afoot,” is currently in revision. He’s written for magazines such as ZYZZYVA and Mother Jones. He’s made recent television appearances on Law & Order and FlashForward, and his latest films are Di Di Hollywood, by Spanish director Bigas Luna, and Valparaiso, for ARTE Television in France. In addition to his roles in films, Coyote has made yet another career out of doing voice-over narrations for more than 120 films. He won an Emmy Award for his work on the PBS series The Pacific Century.

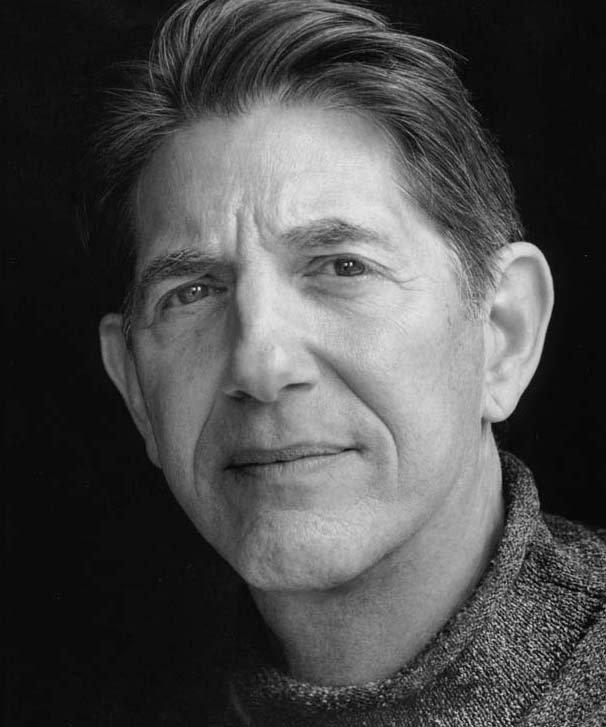

When I arrived at his home, Coyote met me at the door with a fraternal smile and an offer of a cappuccino. He couldn’t have one himself, he said, because of the homeopathic medicine he was taking for his hepatitis C. Though sixty-nine, with his dark hair, trim stature, and casual dress — jeans, gray T-shirt, gold earring — he could pass for much younger. We sat by a display of Native American fans and rattles that he told me were used in religious peyote ceremonies. We spoke between check-ins from his assistant and a call from his wife, Stefanie Pleet.

“I’ve reached the place,” he says, “where I do what I do, not because I think I will win, but because it’s the only way I know how to be human.”

PETER COYOTE

Kupfer: Tell me about the Diggers.

Coyote: The Diggers were a group of friends who met in San Francisco in the 1960s largely through the San Francisco Mime Troupe. We imagined the world we wanted to live in and then tried to make it real by acting it out, inventing a style of invisible public theater that no one knew was theater. For example, we ran a Free Store, to make people consider the roles of consumer, employee, and shop owner. We were trying to create a place for those who didn’t like capitalism, private property, or being compelled to have a piece of paper with someone else’s picture on it to buy what you needed. The Diggers represented the cutting edge of sixties counterculture. We did everything anonymously and for free.

Kupfer: The Diggers predated the height of the Haight-Ashbury scene, didn’t they?

Coyote: Yes, when I moved to the corner of Haight and Clayton Streets in 1964, it was a working-class neighborhood. There were no hippies yet, no psychedelic shops. We were in the right place at the right time.

We tried to create a culture in which we could be authentic. We were on the Left, but we didn’t want to do socialist plays about heroic tractor drivers and streetcar conductors. We wanted to make people reexamine the premises of profit and private property, and we offered what we thought were more beautiful and imaginative alternatives. We weren’t just calling for political change; we were trying to change the culture, which operates at a far deeper level than politics.

Kupfer: But your generation did transform the U.S. political agenda.

Coyote: No, I don’t think we did. We lost every one of our political battles: We did not stop capitalism. We did not end the war. We did not stop imperialism. I can’t point to real political victory.

Culturally, however, we’ve changed the landscape dramatically. There is no city in the United States today where there is not a women’s movement, an environmental movement, alternative medical practices, alternative spirituality, organic-food stores. That is a huge and powerful development that I think will eventually change the political system.

Kupfer: So the political system is the tail on the dog, the last thing to change in the culture?

Coyote: Politicians are not leaders; they are followers. They think that, because they can plunder the public treasury, they are leading. In fact they are terrified of the people. The people are a problem for them to manage, and when they can no longer manage them, they must follow them, or oppress them.

Kupfer: Where do you find the counterculture today?

Coyote: I guess with the punks and the kids with rings through their eyebrows and noses and lips. But when I look at those kids, I get the sense that they are suffering. All the kids I have met who look like punks have been, without exception, sweet people, but they are not hopeful. I think they are trying to keep a part of themselves sacrosanct from the culture by violating norms of fashion and behavior, making music that is so angry and unbeautiful. But the genius of capitalism is the rapidity with which it can co-opt social movements and, via Madison Avenue, sell them back. All my T-shirts are either plain or have pictures of musicians and artists on them. I would never wear a brand and turn myself into a billboard. But now people identify themselves with brands of food, clothes, everything. It’s a triumph of corporate culture.

Kupfer: What is lost when the counterculture is embraced by the larger culture?

Coyote: Nothing. Gary Snyder wrote a poem that says, in essence, when you eat a deer, the spirit of that deer is inside of you, lying in wait for a takeover from within. I did not surrender my values. I may have short hair; I may work for wages; but I am still meditating every single day. Every single decision I make, I ask myself: Is this going to hurt people? Is this going to help? Is this going to move us all forward? The only difference is that now I am on the inside of the culture. I look just like everyone else. You can’t tell the hippies from the bankers. I actually think that’s a good thing.

Kupfer: The San Francisco Mime Troupe has been around for more than fifty years now. How has it evolved since you were a member?

Coyote: I think it is a little less zany than it was, but the players’ skills are more refined, and they have demonstrated that you can continue to survive as an artistic company by making people laugh, bringing your shows to where the people are, and not treating yourself too preciously as artists. The Mime Troupe makes much of what passes as theater elsewhere look thin and self-absorbed.

Kupfer: Do you think theater can be an agent of social change?

Coyote: No, and that’s one of the reasons I quit acting on the stage. A play I cowrote and performed in and directed in New York won an Obie. Here we had done this play attacking the middle-class lifestyle, and instead of stirring something up, we’d been given an award. I realized then that theater was not a vehicle for radical change; it reflected change, perhaps, expressed it for an audience that already “got it.” (Otherwise why would they laugh and clap?) That was when I threw my lot in with the Diggers.

I don’t think theater has ever been a vehicle for radical change. Theater is a vehicle for deepening knowledge about the human species. I am not even sure that the system has to change. People have to change. If people behaved with self-restraint, generosity, and compassion, even capitalism could work. We are never going to create a system that generates fairness, equity, goodwill, and justice. I became a Buddhist in part because I believe that change like that has to start internally and be expressed one person at a time. It is true that a system can advance or repress certain attributes of human behavior, but no set of rules is going to make us perfect.

Kupfer: About the Diggers you write, “My commitment to pursue social change wholeheartedly demanded that I . . . live consistently with my beliefs, not just during performances.” Did this sort of authenticity get you into trouble?

Coyote: It has gotten me into trouble more recently, but not then. We were living so close to the bone then that we did not have to worry too much. Our philosophy was: Why not just do what you believe? It is much more difficult for me today. When I came back to California after the last commune I’d lived in had broken up, I was a single father with a young daughter, and I had to earn a living. I began acting professionally as a source of income. The good news is I was able to save toward my retirement and send both my kids to good schools and colleges, to graduate debt-free. The bad news is that once I took the money, I was a bought boy. I was dependent on other people for a living. I put my family’s needs before my own authentic desires. I don’t mind, and acting has been good to me, but it’s not where I live, and whenever you violate what’s most important to you, you pay a price.

I did many, many projects that I did not like. They weren’t against my principles, but they violated my standards of intelligence and excellence and were often beneath me as an artist. Still, I wasn’t going to take my kids out of private school because I didn’t want to do a Disney movie. There are people who would have done that, though, and I respect them.

One reason that I am shifting back to writing is that it’s a medium in which I don’t have to bend away from my center as much. I write the book the way I want, because I don’t make my living at it. I care less about the movies. At my age there are fewer good roles anyway.

Kupfer: How did you come to Zen Buddhism, and how has it changed you?

Coyote: I started reading about Zen Buddhism when I was fourteen or fifteen, probably influenced by Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and the Beats. My interest picked up when my Digger family and I went to visit Snyder. I was impressed with his gravitas and elegance, his care and deliberation. His community had taken it upon itself to protect where they lived. I found my own community wanting in that regard. As our friendship deepened, I could see traces of his Zen practice in everything he did. Around 1975 I began actual meditation practice, and I’ve been doing it ever since. It’s become a deep and rich vein in my life. I’m being trained as a teacher myself, and I’m currently sewing my robes for my ordination as a priest later this year.

The deeper I go into meditation, the less different from other people I am. Maybe I have some talents or abilities that set me apart on the surface, but I am not all that different from a whole host of people who set out to change the world in the sixties. Some of them did it by organic farming; some of them did it by weaving; some of them did it by working for nonprofits; some of them did it by becoming doctors and nurses; and a number died trying just to protect themselves from the ravages of our political and economic system. I think all of those people were driven by compassion and a desire to make a positive change, and I continue to admire them and identify with them today.

Kupfer: Did practicing Zen Buddhism take you inward and away from your outward activism? How do you reconcile the desire to change society with the Buddhist philosophy of accepting reality?

Coyote: The practice of Buddhism in no way changed my commitment to political work. I did take about ten years off while I learned to pursue politics with less anger and attachment to specific outcomes. There is no exact line between inside and outside, or between self and other, so either-or dichotomies like “inward versus outward” are not really descriptive. Show me where the world ends and you begin. Buddha did not urge people to “accept” everything. That’s a colloquial, Western misunderstanding. He preached a radical transformation based on what worked. He was the ultimate social activist who introduced concepts and practices that have revolutionized humankind. He was not a navel-gazer.

Kupfer: How did drugs influence your life?

Coyote: One of the problems for the Diggers, as we tried to invent a world and act it out and make it real, was the fear that maybe the old world had already irrevocably altered you. Maybe it had trained your imagination, turned it into a mental pet. Maybe what you thought of as new and exciting was just a recycling of the possibilities you’d been given through your schooling. Drugs became a way to break that up, to move beyond the permissible and pursue authentic beliefs and feelings.

Acid was a huge and cataclysmic change. Taking LSD was an awesome experience the first time I did it. It overwhelmed my ego and gave me a sensation of free and boundless unity with the world. The problem was it wore off. And I could see that in the acid culture, a lot of old social forms were simply being replicated. It was as if people believed the experience of acid was somehow a fail-safe fence you had climbed over, and now, on the other side, everything was Enlightened. That was a seductive fraud. You had the Haight merchants turning the hip experience into a product: selling hash pipes and velvet clothes and hiring runaways to work at starvation wages. I did not like that at all. So I foolishly pursued the drugs that my heroes, Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker, had used. That led me to heroin and speed.

Unfortunately when you are young, you do not realize that there is going to be a cost to your body, that whatever insights you gain are going to be paid for in heartbeats and flesh. At a certain point I saw that, if I didn’t stop using drugs, I was going to die young and unfulfilled, without having made an impact and without having been a responsible father. So I cleaned up and went into a Zen monastery. I began dating a woman there, whom I subsequently married. I also undertook a serious course of psychoanalysis, and I pursued that diligently for ten years, in tandem with Zen meditation. I changed my life.

I did not surrender my values. I may have short hair; I may work for wages; but I am still meditating every single day. Every single decision I make, I ask myself: Is this going to hurt people? Is this going to help? Is this going to move us all forward?

Kupfer: Did you find it difficult to clean up from hard drugs?

Coyote: Not particularly. You have a bad week or so. The trouble is staying clean, taming the pit bull that’s been chewing on your innards your entire life, the one you’ve been bribing to stay out of your consciousness. After I had cleaned up physically, I needed to change my life, and Zen practice and psychotherapy and working as the chair of the California State Arts Council became the bedrock of that change. I tried to understand as exhaustively as I could how and why I had been haunted, and I ended the haunting.

Kupfer: What did your use of hard drugs teach you?

Coyote: It taught me not to do them. It taught me how corruptible we all are; if we are not paying scrupulous attention, we can use the posture of integrity and the importance of our political ideas to cover up a host of unsavory and self-destructive practices. It doesn’t have to be hard drugs. You could be treating women badly. You could be oppressing people in your organization. You could be intolerant and dogmatic. Without what Alcoholics Anonymous calls a “fearless moral inventory,” and without a community to keep you straight, it’s almost impossible to stay out of trouble.

Hard drugs also teach you that there is no escaping your life: no matter how high you get, the drug wears off. It was partially my pursuit of a high that wouldn’t wear off that led me to Zen Buddhism.

Kupfer: How did you talk to your son and daughter about drugs?

Coyote: I was candid with them. From early on I let them know what I had done, what it had cost me, and how many friends I had buried. Because I was not hysterical about the subject, they were open to discussion and at least listened to my advice. I understood the social pressures confronting them. I told them I didn’t care if they smoked a joint or drank a beer at a party, but anything that had been chemically concocted by some doofus who might not have washed his hands or measured correctly could turn them into a vegetable. About the time I quit hard drugs, there was a synthetic heroin floating around Haight-Ashbury that gave people tremors for the rest of their lives after they’d used it just once.

Kupfer: What scars do you carry from that period of your life?

Coyote: I have a few, all related to my own bad choices or lack of consciousness. Physically I carry the hepatitis C virus, which, if I can’t stop it, will cut my life short. Emotionally there were people I hurt by not being sensitive; by being exploitative; by using my charisma to get what I wanted; by not being as kind as I could have been. Once you wake up and see your own behavior clearly, it is a kind of wound, because it makes it impossible to reflexively think of yourself as a “good person.” It has taught me to be very cautious. It has taught me that we all have within us the potential to do great damage to the world and to other people, and the only thing that saves us from doing it is our self-awareness.

Kupfer: What mistakes did the counterculture make in the sixties?

Coyote: My friend Freeman House argued at the time that the idea of a “counterculture” condemned us to marginality. He was correct, though I didn’t understand it back then. There were many people who might have shared our ideas but who did not like our dope or our long hair or our indulgent behavior. We lost the opportunity to communicate with those people. We were not good organizers. We were artists. The Diggers was a kind of art project that evolved into the Free Family, which was a nationwide group of people who were living in communes, but our separation from the majority culture also diminished our effectiveness and the degree to which we could help others.

The communal movement grew because, if you did not want to trade your life for wages, you had to learn how to live cheaply. We also wanted to minimize the energy that we used and how much we took from the world. We pushed it a little hard maybe, but that was the way you had to live if you had no money. You could have a household with thirty people basically using two welfare checks for their cash needs and sweat or barter for everything else.

Kupfer: That sounds quite efficient.

Coyote: I would still be living that way if I could have provided medical care and education for my kids. If you want to reduce the energy that you are using, cooperative living makes a lot of sense. A refrigerator can serve ten people. A stove can serve ten people. Not everybody needs a three-bedroom house (though they do need private space — in our culture, anyway). But you couldn’t afford to go to the doctor. You couldn’t get your kids into good schools. So I was eventually forced to participate in the larger culture. The way we lived in the sixties looks more and more prescient as the U.S. moves into the future.

Kupfer: How did the Free Family start?

Coyote: By the time I left the Haight in 1968, the media had generated so much interest in the neighborhood that it was overrun by runaway kids from all over the country, and it was not my dream to run a soup kitchen. I wanted to learn about how to be in a community.

As we dispersed out of the Haight, the Diggers met other families, like Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers from New York and the Free Bakery from Oakland. These various groups joined together and became the Free Family. It was an overarching alliance of sympathetic souls, like the Sioux Nation, which was a union of seven different tribes.

Kupfer: In the Free Family you had no leaders or claims of ownership. Was there a downside to that approach?

Coyote: Yes. Here’s an example: You wake up in the morning and go to the sink to wash your face, and it’s a black, greasy mess because one of the guys who was ripping apart a tractor engine the night before washed up and left the sink a wreck. There is no revolutionary principle you can point to that says the sink has to be clean. It is a question of personal preference and consideration for others. Or you come home one day and find that all the doors have been taken off the bathrooms because somebody has decided that privacy is a “bourgeois ideology.” Or some subset of the group dictates that you can’t be in a committed relationship; you can only sleep with someone three times, and then you have to move on to another partner, because monogamy is bourgeois. There was no authority to say, “That’s nuts!” so we had to talk over every issue as a group and hammer things out until we came to an agreement.

We learned that for every given task, someone in the group was the natural leader, and if we all just listened to that person, everything would go fine. When that project was over, that person would drop back into the group. Problems arose only if that temporary leader tried to hold on to that authority.

Kupfer: Did you succeed in avoiding the larger economy?

Coyote: We did try to build an alternate trade route of small, independent communes. We compiled a list of surpluses and needs as we traveled, and we printed up a catalog and mailed it to everybody. If you go to the Diggers’ website today, you will see that some people never abandoned that system. Some of them have attacked me for working for wages, as if they were totally outside the economy. They are writing their critiques of me on a computer! [Laughs.]

Kupfer: Do you find lessons from that era applicable to the growing localism and organic-agrarianism movements today?

Coyote: The new localism is not new. We are just rediscovering ways of developing resources where we live and then trading with other people who have different resources. I don’t grow coffee here, but if I buy it from a fair-trade organic collective in Guatemala, that, to me, is ethical trade. Those are authentic, self-governed people making their own decisions about what is best for their region and their community. It is actually an extension of what communards were doing in the sixties.

Kupfer: What killed the commune era?

Coyote: I think it was a mix of forces. The Free Family communes were really anarchic and didn’t have rules. Most of us worked hard, but if some people didn’t feel like working, we didn’t compel them. So maybe you were depending on someone to fix your roof, and they didn’t do it, and you got wet when it rained. Or maybe you did not want to share what little money you had with somebody who sat around and smoked dope and played the flute all day.

When children came along, they began to exert new pressures. If you are waking up at five o’clock every morning because that’s when your baby wakes up, you can’t have Wino Eddie playing the tom-tom at 4 AM.

Another factor was that we did not yet have a vocabulary with which to talk about our feelings. We were busy being heroes and remaking the world, but a hero isn’t supposed to get jealous if his wife sleeps with somebody else. A hero isn’t supposed to get upset because the sink is a grease pit. All these things began to fray the body politic of the commune. The last commune I lived on, which was in the Delaware Water Gap region of Pennsylvania, finally broke up because the bank foreclosed on the land I’d inherited from my father. But I think by that time many people had begun to lose interest.

Kupfer: Your father was a stockbroker, and after he died, you did his job for a while. What was that like, dividing yourself between Wall Street and the commune?

Coyote: It was the worst time in my life. My dad owed millions when he died, and my mom had not worked in thirty-five years. People were demanding money from her at the funeral. She had to sell two homes, and we were living in the third, which was also on the block to be sold.

My dad’s old business partner came to me and said, “You could be doing more to help her.” He felt that I could take over my dad’s business, and, on the basis of my being there, we would be able to float a year without interest on the outstanding loans. Perhaps I could still make enough to pay off the creditors.

I accepted the challenge, got my license as a registered representative entitled to be a stockbroker, and went into my dad’s business. But my dad had never taught me anything about money. He’d wanted me to be an English professor or an artist. I was so out of my depth. It was like what F. Scott Fitzgerald says in his journals: “One of those tragic efforts, like repainting your half of a dilapidated double house.” All my dad’s best customers had been taken by the salesmen who had left the company. I was given a book about six inches high, listing every business in the state of New York that employed two or more people. I sat in this barren little office on Wall Street, wearing a suit and tie and making cold calls all day long. In an entire year I made one sale.

I had lived my whole life in judgment of this system and the people in it, and I just couldn’t pull off pretending to be one of them. It was a really bad time for me, and it led to a lot of drug use.

If you are waking up at five o’clock every morning because that’s when your baby wakes up, you can’t have Wino Eddie playing the tom-tom at 4 AM.

Kupfer: What was your role in the very early days of the antinuclear movement in the Delaware Water Gap region?

Coyote: In 1972 or ’73 the local utility, Metropolitan Edison, wanted to dam the Delaware River and declare eminent domain on my land and many of my neighbors’ land as part of a plan to build a nuclear power plant and send the power to New York City. We were considered expendable, I suppose. So my friend Kent Minault, a fellow communard and Mime Trouper, and I started to read up on nuclear power. The more we read, the more frightened we got. We disseminated a lot of information locally, printed up handbills, and urged people to come to the Northampton County Board of Supervisors meeting to discuss this issue. More than three hundred people showed up. The firehouse was jammed. Two PR guys from Metropolitan Edison were there in their white jumpsuits with slide rules in their pockets to tell everybody about the project.

I got up and spoke for ten minutes about what I had learned, and Kent did another ten. We covered the dilemmas of nuclear power: The waste is the most carcinogenic substance on earth, with a half-life of over a hundred thousand years. How were we going to maintain safety for a hundred thousand years? Humans are not perfect. And why was the plant being built here to power New York City? And so on.

When I was done, there was dead silence. The board president asked the two PR guys if they’d like to rebut, and one of them said, “We aren’t ready for something like that.” The room exploded, and right then and there we formed the Delaware Water Gap antinuclear movement. Two members of the board of supervisors joined on the spot. It is still running today. Not bad for a couple of hippies, huh?

It was an example of active citizen engagement that stopped a huge power company. I am still fighting the nuclear industry. It is the most expensive method of generating power. It is filthy, not green at all, and if you include the energy it takes to build the plant, the carbon released in the production of cement, and the thermal discharges that endanger wildlife, it’s an ecological disaster. They haven’t made an inch of progress on the waste, which still has to be kept completely out of the biosphere for a hundred thousand years! It can’t be done. Forget it. You can’t avoid the “oops” factor with humans, and you can’t afford an “oops” with a deadly material that stays poisonous forever. [Note: This conversation took place prior to the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan. — Ed.]

Terror is terror; it is despicable. But nothing is ahistorical. Nothing comes from nowhere. The way that we are systematically denied knowledge of the antecedents of events makes Americans sulky, ignorant, uninformed, and self-righteous, and it is killing us.

Kupfer: What are your thoughts on the nuclear-power industry’s effort to sell itself as a solution to global climate change?

Coyote: They are opportunists. The bill for the problems with nuclear power will come long after today’s executive is retired. It’s the same with Congress: the real problems caused by any legislation will come after Senator Blowhard is out of office. There is no downside for them, and in the short term they get paid off. If you want to make a good investment, buy a congressperson. The returns are outrageous. When I was researching my book, I learned that the timber industry spent $8 million to preserve its logging-road subsidy, valued at $458 million. Drug companies make campaign donations in the millions and receive patent extensions worth billions.

To me nuclear energy and nuclear weapons are the most palpable threats, besides global warming, to life as we know it. Because we have manufactured fissionable material in such volume, it is vulnerable to terrorists. They don’t tell you about how our nuclear-plant security has failed. Every simulated terrorist attack on a nuclear facility has succeeded. The simulated attackers have overwhelmed the plant and could have done whatever they wanted. We are gambling with the lives of our great-great-great-grandchildren, and I am not going to do it. I am never going to support nuclear power.

Kupfer: Through your travels you have become a veritable citizen diplomat. What brought you to this role?

Coyote: I’m not sure I know what a “citizen diplomat” is. I try to be a good citizen. I realized that there is no conflict the U.S. is engaged in now, anywhere in the world, that is not blowback from some prior problem we failed to solve. When we hired Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan to fight the Soviets, all we wanted to do was get rid of the Soviets. It never occurred to us to worry about arming radical Islamic jihadists. Then, when the Russians left, we rolled up our entire intelligence apparatus as if we’d never need it again, in the same way we throw away spare parts in this culture. No good mechanic throws away spare parts. You never know what you are going to need, and conservation and thrift are indices of maturity and wisdom.

When al-Qaeda took out the World Trade Center, most Americans had no idea that they were the victims of blowback. I am not saying it’s our fault; I am not making any excuse for Osama bin Laden and the terrorists who killed those poor people. Terror is terror; it is despicable. But nothing is ahistorical. Nothing comes from nowhere. The way that we are systematically denied knowledge of the antecedents of events makes Americans sulky, ignorant, uninformed, and self-righteous, and it is killing us.

Kupfer: What did you learn on your recent journey to the Middle East?

Coyote: That the Middle East needs an honest broker, and the U.S. government can’t be one, because Israel is the leading recipient of our foreign aid, and we let them do whatever they want in the region. I don’t care how corrupt the Palestinian leadership is; the Palestinian people are just like the Israeli people and the American people. They want to wake up in the morning and do something productive and take care of their children. But the Palestinians can’t do that, because the preponderance of power rests with the Israelis, who have been moving, despite protestations, to make a two-state solution impossible. I refer people to a book called The Iron Wall, by the Israeli historian Avi Shlaim. Every year that goes by, more settlements are built in the Palestinian territories; more walls are built around them; more highways are built through them. Palestine’s being carved into isolated enclaves. And Israel supporters in the U.S. routinely decry any criticism of that as “anti-Semitic.” I am a Jew, and I have relatives who call me a “self-hating Jew” because I suggest that the Palestinians have a pulse and are not a degraded form of our species.

For the U.S. to be an honest broker, it has to say no to Israel sometimes. I am already receiving propaganda e-mails about President Obama’s “war against Israel,” even though Israel still gets billions of dollars in aid. I support Israeli culture and am quite proud of it in every respect except its treatment of the Palestinians. Israel needs to be brought to heel, and only major powers can do that. If you look at how the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is cited as the source of grief and rage in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Indonesia, and Arab cultures all over the world, our unconditional support for Israel is pretty damn expensive for us.

I am in solidarity with all suffering people. I am speaking for the Palestinians here because they rarely get a voice in this country, unless you listen to Berkeley’s listener-sponsored KPFA radio or follow the work of Edward Said or visit Palestinian Web pages.

Kupfer: Do your views put you in conflict with your family?

Coyote: Yes, because they think that everything they read is fact, and everything I read is propaganda. At least one-third of Israeli Jews are in the peace movement there, but many American Jews prefer to call those people “crazy” too. I think it’s because American Jews are crazed with guilt about not living there and are far removed from the conflict and never have to worry about going into the pizza parlor and getting blown apart or not having their kids return home alive. The Americans are the ones who are the most obdurate, hammering the hardest about what monsters the Palestinians are and how they have no value as human beings. It’s the same thing we said about the Vietnamese; the same thing we said about the Japanese; the same thing we said about the Native Americans; the same thing we said about the Filipinos; the same thing we said about the Cubans. Is anyone getting the picture yet? If I’m shocked at anything, it’s that the American people never seem to wake up to the same old play staged with new costumes.

Kupfer: You actually met with Khalid Mishal, the head of Hamas. What did you two talk about?

Coyote: First I told him I was a Jew. He pointed around the room, where about ten men were sitting on chairs. “He’s a Jew,” he said pointing to one, then another, and a third. “We don’t have any problems with Jews,” he said. “Our problem is with a Jewish state.” I asked him why Hamas would not recognize the right of Israel to exist. He laughed and said, “It sounds so fair and reasonable, doesn’t it?”

I said, “Yes, it does to me.”

He responded, “But don’t you see? It is a trick question.” The Palestinians are realists, he told me. They can make a long-term treaty with Israel, but asking them to acknowledge Israel’s right to exist would be like asking Native Americans to admit that Europeans had the right to come in, take their land, and commit genocide. They are never going to say that Israel had that right, and the Israelis know that. It is a ploy to fool the West.

Kupfer: What has U.S. foreign policy done to the country domestically?

Coyote: Pursuing only our own self-interest has made us a mess. We are the richest, most powerful third-world country on the planet. We’ve got income disparity greater than Saudi Arabia’s. We’ve got crumbling infrastructure. We’ve got uneducated children — 30 percent of the kids in public school drop out before they graduate.

Look at some of the older, more stable cultures around the world: Their organizing principle is not self but community. You don’t just do what is good for you. The Golden Rule has a real flaw in it that indigenous cultures pick up on immediately. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” puts you and your personal standards at the center, and it allows you — if you are antisocial — to stay at home and do nothing. Any ancient culture would say you don’t have the right to do that; you have responsibilities to the old, weak, and infirm, to the widows and orphans. You can’t just do whatever you want. That is the difference between community-mindedness and self-interest. Our culture is paying the price of self-interest as an organizing principle.

Kupfer: The war economy is continuing unabated under President Barack Obama. Do you think there will be much of a change in the remainder of his term?

Coyote: I have great faith in Obama: in his intelligence, his probity, and his humanity. Despite that, I am deeply disappointed by nearly everything he has done. I think his agenda is to repair the infrastructure, create the basis of a green twenty-first-century economy, and fix education and healthcare. If, to do all of that, he has to let the bankers and the military have their way for a while, he will. He also has to know that, unless he can resurrect the economy, he will never get a second term, so I think that figures into his thinking.

I am deeply afraid, however, that just as Vietnam wrecked Lyndon Johnson’s progressive agenda, Afghanistan and Iraq and Pakistan are going to wreck Obama’s. We are spending so much money on these fruitless wars. It would be cheaper to buy the entire poppy crop of Pakistan and Afghanistan directly from the farmers, undercutting the economic base of the Taliban, than to pursue this war. We should secure the nukes and let the Pakistanis and the Afghans work it out. They are going to have a bloodletting there. If we had decent intelligence, we would know where the nukes are. I’m afraid we don’t.

We ought to be getting rid of our own nukes. We are tasked with that as signatories to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. It is the weapons themselves, not who owns them, that are the threat to the world. We can’t tell the Iranians not to have nukes while we have thousands. We can’t tell them that they don’t get to play in the big-boys club. Iran is an ancient empire. They are not going to take a back seat to the United States. They are fully aware of the difference between how we treated Iraq, which had no nuclear weapons, and North Korea, which did. Our invading one country and not the other clearly demonstrated to every nation the value of having the bomb. Any country that is antagonistic to the United States now wants a nuclear weapon, if only for their own security. Why won’t we give Iran a no-first-strike guarantee? Without it, why shouldn’t they fear us and pursue their own deterrent? That’s just rational. They’ve already seen our intentions toward them when the CIA overthrew their elected president, Mossadegh, in the 1950s for having had the nerve to nationalize the country’s own oil reserves.

Iran is going to arm itself for the worst, and that is partially our fault for our failures of diplomacy. We’re still pissed off about the Iranian Revolution in the 1970s, when they ended the shah’s reign and imprisoned our diplomats. But we do not relate that to the fact that we overthrew their leader in the 1950s. We just begin our history of Iran with the overthrow of the shah. That is what I mean by blowback.

Kupfer: What did you think of the Republicans branding Obama a socialist?

Coyote: I am a socialist, so Obama being called a “socialist” is ridiculous. A president who took single-payer healthcare off the table, who put the same men who ruined the economy in charge of it?

Kupfer: Do you think we can solve the problems we are facing using the capitalist system?

Coyote: No. People rightly feel that business has to participate in any solution, but can you imagine any business not trying to sell you new-model widgets that are better, faster, brighter? Does Toyota want you to keep a Prius for fifteen to twenty years? I had a Dodge wagon for thirty-two years and a little BMW for twenty-two years. They were great cars, built to be fixed. Today’s cars are built to be replaced.

Capitalism requires growth. It has to produce more wealth, which means it has to turn more of the world’s resources into commodities. It has to monetize the biosphere in one way or another. I think manufacturing will get more efficient, but, at the same time, I think that it is already too efficient. We are fishing the oceans too efficiently. We are cutting down trees too efficiently. I don’t think you can be both green and capitalist. If you are accreting capital faster than nature grows it, you’re using up the world. The only thing that grows continuously is cancer. All other natural systems reach a climax form — a steady state. We need to do this. Why does everything have to grow and get bigger and more profitable? It is certainly not for the health and prosperity of working people.

Kupfer: Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future?

Coyote: I am a pessimist. There was a study done somewhere that said pessimists are more often correct in their predictions, but people more often choose to follow optimists. Americans have been indulged for two hundred years. We had the incredible wealth of a new, untapped continent as ours — after we’d killed the original inhabitants. We were so rich we could hardly make a mistake. We have lived an unrealistic lifestyle sustained by massive debt and massive expenditures of our natural capital. We have trained our citizens to feel entitled. Whatever they want, they want it now; they don’t want to wait.

What, other than his wealth, makes Donald Trump, the deity of vulgarity, worth one column inch of newspaper? The only reason is that he is rich, and because of that he is enshrined, lauded, and respected. When people are elevated to the top of the social pyramid solely for making money, how can I not be pessimistic? In the meantime the people who care for and teach our children and who nurse us and our relatives are barely scraping by.

I see a lot of wonderful efforts being made, but you can’t possibly recycle Coke cans faster than Coca-Cola makes them. There have to be industrial-scale changes if we are going to survive. That means industrial-scale reallocations of resources, taxes, and investment.

I just read that the Chinese are building new high-tech, steam-powered coal plants that are over 40 percent efficient. They gasify the coal before they burn it. They are building one a month, and for every one they build, they are retiring an old, polluting plant. The U.S. is still arguing about building steam-powered coal plants in this country. Should I be optimistic or pessimistic? We are still making four-hundred-horsepower cars in this country. Should I be optimistic or pessimistic? People are still living in 2,800-square-foot homes like mine. I have changed every light bulb in this house to an LED. It makes a minuscule difference. I drive a biodiesel car; I drive a motorcycle that gets more than forty miles to the gallon. I do everything I can do. It is all minuscule in comparison to the scale of the problem that needs to be addressed. And I represent the point of the spear. I am a hippie radical anarchist environmentalist with plenty of money. What about all of the Americans who are just trying to get by? They have been the victims of billions and billions of dollars of advertising telling them that, if they buy the right products, they will have higher status and a better life; they will have more fun. After 9/11 our president stepped up and told us all to go shopping. If it weren’t so horrific, it would be funny.

Kupfer: How does being in the final third of your life affect the projects that you are choosing?

Coyote: It has made me extremely focused. Unless they can stop the virus in my liver, my years are indisputably limited, and I don’t know how good they will all be. I am getting ruthless in cutting away luncheons and casual meetings to concentrate on my writing, the legacy that I want to leave behind, and doing what I want to do.

I recently officiated a ceremony at which the Dalai Lama was present. He said that expecting results for good works in your lifetime is a kind of selfishness; that you need to detach from that expectation and just do what it is you are doing.

Every generation is a life-and-death struggle between wisdom and ignorance, and there are no guarantees that wisdom is going to win. We have to try to be as human as we can be, and as kind as we can be, and detach from our need for results.

Kupfer: If you could go back in time fifty years, what advice would you give your younger self?

Coyote: Remember that you have only one body. Don’t do anything that is going to adversely affect your health, because your health steals away faster than you can possibly know. Everything takes four times as long as you think it will. Don’t be impatient. Don’t use urgency as an excuse to be unkind or violent. Just keep doing your work, keep pushing straight ahead, dedicate your entire life to it, and don’t fret too much about results.