During the late eighties there were a lot of people coming of age who saw and felt the failures of the older generation in ways that bred cynicism. This cynicism drew us together, and we embraced noisy music that mirrored the dissonance in our heads, wrangling beauty out of chaotic feelings.

Being in a band felt vaguely like a political act, because we were working to create some kind of path outside of an industry that constantly tried to sell subversiveness back to the youth. We booked our own shows, made our own T-shirts and posters and zines. We wanted to have some kind of impact. Despite our sense of hopelessness, we actually had songs with political content. We struggled with the desire to be performers while also seeing performance as so much artifice. It can be hard to get out from under the crush of irony.

Two friends and I moved to Providence, Rhode Island, in the summer of 1990 to focus on our band, Sleepyhead, which we had started in our New York City dorm the previous fall. We walked down the street with a sign saying we needed an apartment, and within about an hour we’d arranged to sublet part of a house on Prospect Street. It was right at the time when everyone was moving out for the summer from Brown University, and I found a double mattress on the street and dragged it back to my room. I think we paid a hundred dollars a month. Our first night there we went to a house-party concert, and it was one of the greatest things I’d ever seen — explosive, tight, and chaotic. I had just taken my first real photography class, and I was firing on all cylinders creatively for the first time in my life. That fall I returned to New York with the sense of commitment to document the underground music scene there.

The thing I miss most about being in a band is the travel and connection with others. I recall the sense of freedom and adventure that touring entailed. To be fair, there was an enormous amount of boredom and long drives, too. We didn’t sell many records or draw crowds. We barely covered gas money on these trips. We stayed with friends, family, or the first person who bought a T-shirt. Sleeping on people’s floors can get old, but we brought cushions. Lots of bands I barely knew stayed at my New York City apartment on Avenue B. One guy somehow locked the door handle from the inside on the way out, and we had to break it off. Three of us lived in a tiny place where none of the rooms had doors. We had way more roaches than money, and I ate rice and beans four to five nights a week. I once went on tour with my bike locked up out front on the street. I was surprised to find it still there when I got home weeks later. It was gone the next day.

We were all just kids, really, not so emotionally mature or settled into our sense of self. I’m still not settled into my own. People made a lot of bad decisions in that time and place. Lots of people had heroin issues, and people I cared about became ghostlike, and some died. Others pulled through and thrived, but it was messy.

It was never wholly about music; it was also about being part of a community of like-minded misfits and broken dolls. I felt a responsibility to capture these bands and that world specifically because it seemed like nobody else was. Being in a band connected me with hundreds, if not thousands, of others trying to make art outside the expectations and demands of the system. I think finding that community saved me in ways I can’t even articulate. None of it was easy, but all of it had meaning.

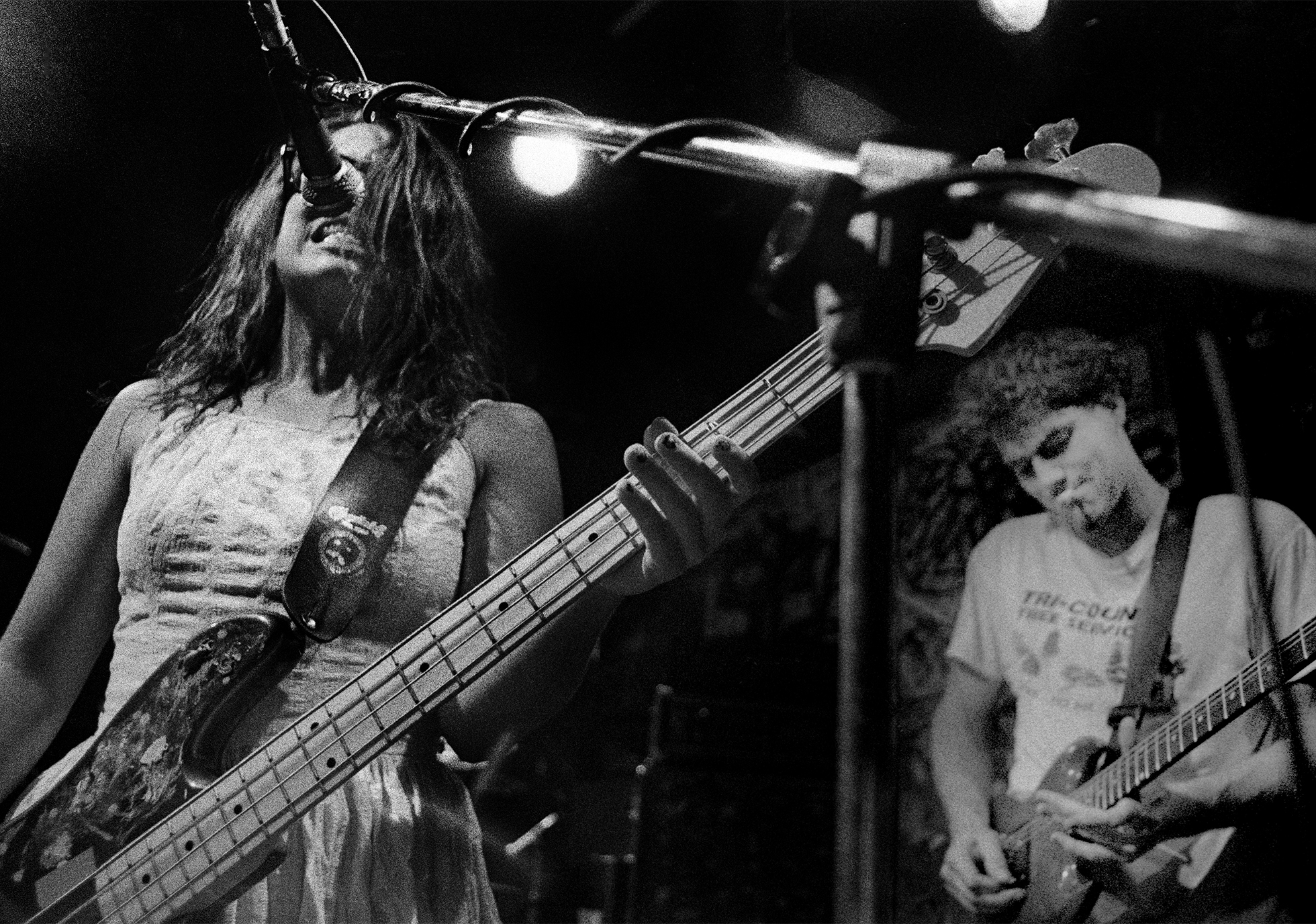

Stereolab plays at Maxwell’s in Hoboken, New Jersey, on their first visit to the U.S., 1992.

Backstage at CBGB in New York City during a Dungbeetle show. Dungbeetle played with the photographer’s band, Sleepyhead, many times over the years.

Sonic Youth performs for an abortion-rights benefit concert at the Paradise in Boston, 1990.

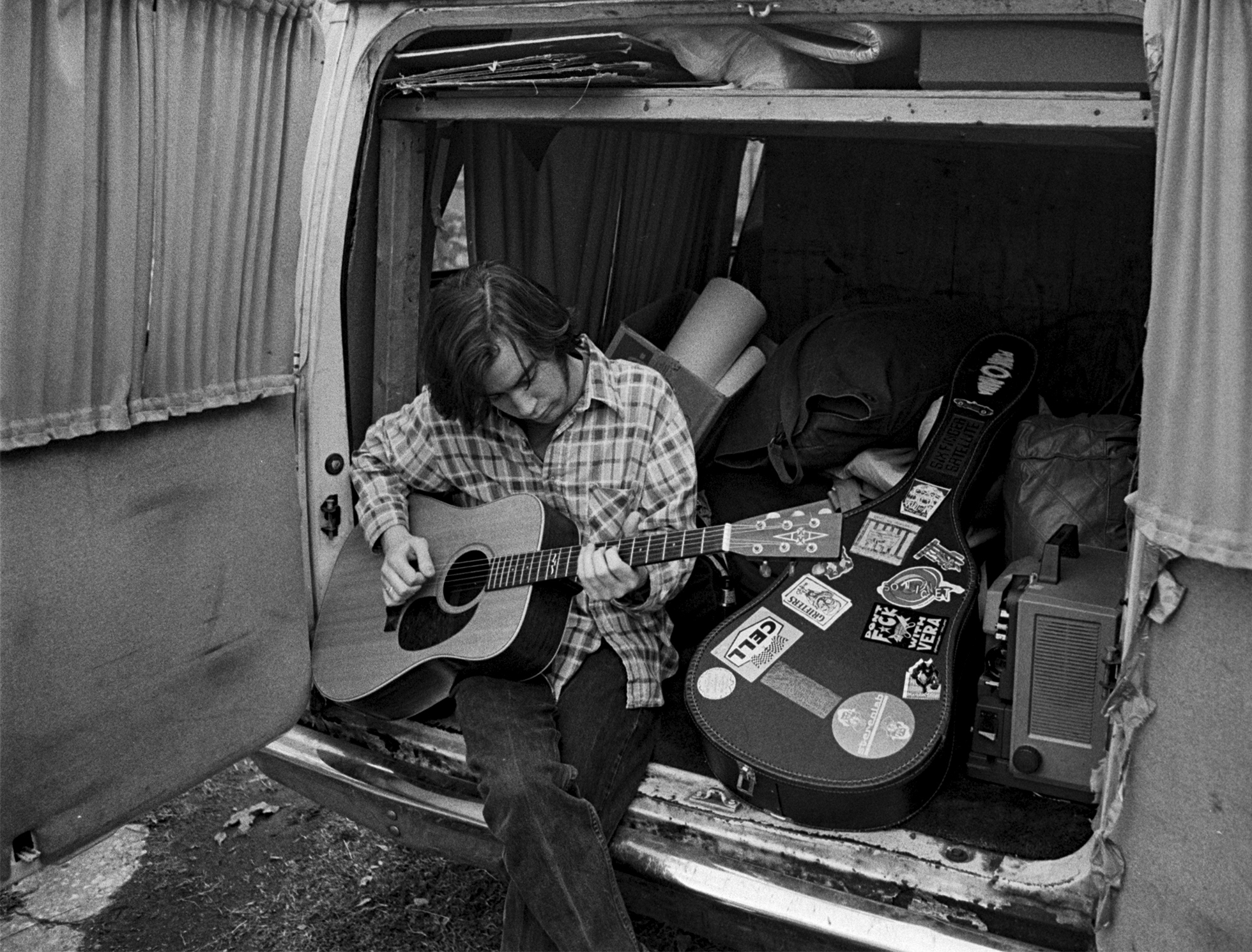

Chris O’Rourke of Sleepyhead warms up for a show in the mid-1990s.

The Thinking Fellers Union Local 282 at CBGB, circa 1991.

Jackie Arthur behind the bar at the Snake Snatch Lodge in Knoxville, Tennessee. After the show she would help the bands find a place to sleep.

While on tour, Sleepyhead spends the night in a former frat house in East Lansing, Michigan.

In the early 1990s the photographer shared a 450-square-foot New York City apartment with two friends. The bathroom had no sink, so they hung a mirror above the stove.

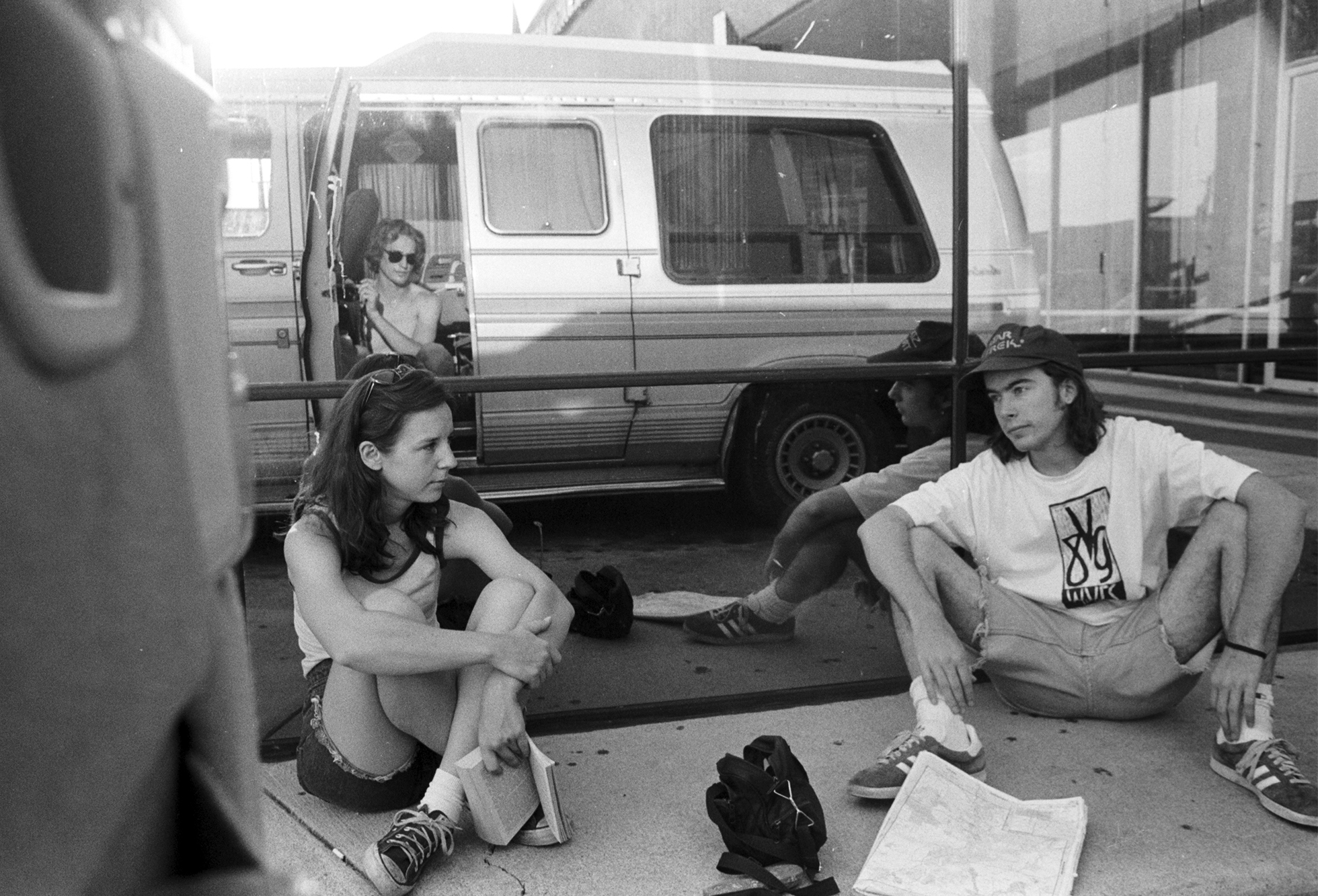

Sleepyhead has an official band fight in Houston, Texas, on the band’s first cross-country tour. The photographer can be seen in the reflection, sitting in the van.