For millennia humans have gathered in circles, warmed ourselves around a fire, and told our stories. Often there has been ritual involved, something that separates this practice from our frenetic daily lives and sets aside a time for speaking and listening from the heart.

As executive director of Center for Council in Los Angeles (centerforcouncil.org), Jared Seide has helped keep this tradition alive in crowded cities, inside classrooms and assisted-living facilities, and even within the thick walls of prisons. The method he uses is called Council: People sit in a circle. They set an intention to speak spontaneously and authentically, and to listen generously and without judgment. They use prompts to get the stories flowing. They pass around an object designated as the “talking piece” to indicate whose turn it is to address the group. Sometimes people bring in objects that are meaningful to them and talk about those.

It may sound simple, but Seide says it can be transformative in its ability to cultivate compassion and reduce defensiveness and aggression. He explains that when he teaches Council to a new group, it isn’t so much an act of learning for them as it is an act of remembering. This is what humans have always done; we have it in our DNA. Council might have been recognizable to Benjamin Franklin as what he witnessed at Iroquois “talking circles.” It resembles what people in Sierra Leone would call Fambul Tok (“family talk”) and what Quakers call Friends meetings. It incorporates aspects of Buddhist meditation gatherings and the Nonviolent Communication techniques developed in the civil-rights era. It is nothing new. Yet it is largely absent from modern life.

Seide was fascinated by storytelling from an early age. He became a child actor and studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London before earning his BA with a concentration in theater arts from Brown University in Rhode Island. After graduation he went to Hollywood and worked as an actor and screenwriter. He says he found “the commoditization of the story” to be a lucrative career, but ultimately an unsatisfying one.

He was introduced to Council when his daughter’s elementary school adopted the practice to address racial tensions. After seeing how Council helped his daughter find her voice and transformed the school into an “empathetic, cohesive community,” he became a student of the process. Seide studied Council intensely at the Ojai Foundation, a Southern California educational and retreat center established by medical anthropologist and Zen priest Joan Halifax, where indigenous teachers and contemplative wisdom traditions were celebrated over many years. Seide built up the foundation’s Council initiative, and in 2014 he became director of the spin-off organization Center for Council, which aims to bring the practice to a wider audience that doesn’t have access to private retreat centers. He is also a member of the Zen Center of Los Angeles, a graduate of the Buddhist chaplaincy program at the Upaya Institute in New Mexico, and has served as a “Spirit Holder” for the Zen Peacemakers.

What compelled me to sit down and talk with Seide was his work with people in difficult settings — specifically Hutus and Tutsis seeking restorative healing two decades after the genocide in Rwanda, and inmates and correctional officers in California’s prisons. One prisoner at Salinas Valley State Prison says that his Council training “allows me to reconnect with my innocence and vulnerability.”

I have used Council in my own work as an educator, sitting in heart-opening circles with squirrelly middle and high schoolers and white-knuckling it through circles with fellow educators who were not ready. I have even brought Council into my relationship with my husband and sons, who appreciate the space that opens up when we get out the talking pieces and listen deeply for a while. In Council no one is the authority, and each person in the circle is the expert of his or her own story. I have found it a powerful tool for building empathy and making sense of our lives.

This interview began years ago but got interrupted by the birth of my second child. We picked up the thread again more recently, and I learned how Seide has brought Council to law-enforcement and health-care professionals, to help them be more present in their high-pressure jobs. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic he is finding ways for people to maintain meaningful connections in a time of social distancing.

JARED SEIDE

Kight Witham: In Council people sit in a circle and share their stories one at a time while others do their best to listen without judgment. That may sound to some people like a support group. How is Council different?

Seide: It’s a nourishing, therapeutic environment, but it’s not therapy. It’s not a treatment for somebody who is in need of mental-health support. There’s no single expert there who has the answers, who can fix you. But all of us care, and we agree to give each other permission to speak and to unburden ourselves. We practice listening intentionally, without the need to judge or analyze what’s being said, and we speak spontaneously and without an agenda. We’re able to create an environment where we can just be human together, and that’s enormously sustaining, because in the circle there are likely others who’ve been where you are and who have resources you didn’t realize were available. We come as we are, ready to be the best version of ourselves we can be in this moment, on this day. That’s what we bring, whether it’s tears or laughter, goofiness or seriousness. That’s what the group gets, and that’s OK.

Kight Witham: You’ve brought Council into some difficult environments: prisons, law enforcement, hospitals. Tell me how you went to Rwanda in 2014.

Seide: We knew the twenty-year anniversary of the Rwandan genocide was going to be a big one, so Bernie Glassman [co-founder of Zen Peacemakers] asked me to help support a Bearing Witness retreat, which would be an opportunity for people from Europe and the U.S., as well as Rwanda and other African nations, to come and participate in five days of bearing witness to the atrocities. Bernie had been leading similar retreats to Auschwitz for two decades.

In a hundred days in 1994, more than a million Tutsis were slaughtered by the majority Hutus. [The mass killings took place during a civil war in which Tutsi rebels were challenging the Hutu-led government. — Ed.] It was a genocide so amazingly brutal it’s almost inconceivable. It’s incredibly difficult to listen to the stories of the actual events. So we needed a container that would take into account how unbearable it is to hear those stories.

The Bearing Witness retreat centered on a place called Murambi, which is a memorial on the site where fifty thousand Tutsis were brought and then, one day, between the hours of 11 PM and 9 AM, massacred, mostly with clubs and machetes. Their remains were buried in mass graves, which were later exhumed, and the bodies that had been preserved — hundreds of them — were laid out at the memorial so that people could recognize and remember what had happened there.

A variety of people showed up to this event, including direct survivors who had the physical wounds of what had happened: scars and loss of limbs and hands. Also some perpetrators had come to beg forgiveness.

Twenty years after the genocide, the convicted perpetrators were about to get out of prison and go right back to the villages where they’d committed their crimes. There was a great need for a conversation about how these folks might reintegrate. We created a community-based model, where the former prisoners and their neighbors would be given the opportunity to open up and start to unpack some of the feelings that had been with them for two decades.

We wondered: Was there some conversation that would help us understand the human experiences of being victim or perpetrator, of being safe or being hunted? We wanted to see if we could find some way to support each other, to recognize our stories in each other, and be allies.

Kight Witham: What was it like to sit in the circle with survivors and perpetrators?

Seide: I couldn’t even imagine the carnage, the gruesome acts. It was disorienting and difficult. When we sat in those circles and people were able to tell about their individual experiences — after we got beyond the drama of blood and machetes and screaming — I started to get a deep sense of what it was to live in a place where nothing makes any sense.

A woman spoke in harrowing detail about losing her teenage children and her nine-month-old child. The next person spoke of hearing stories of relatives and visiting places where murders had happened. Then the talking piece made its way to a person in the circle who had been part of the group that had terrorized the first woman’s family; who’d been given a machete and had used it that night. He spoke of the murders he’d committed twenty years earlier and had lived with since then; of feeling that he had been taken over by the devil; of not knowing why the devil had chosen him to do the most evil thing possible; of trying to make sense of it, to figure out what he could do, how he could live after having done something like that. It had destroyed his life. Hearing his story didn’t actually make things any better, but it brought a complexity to the situation. There was more to it than the simple story of the good guy and the bad guy. The person to whom we had ascribed all this evil was suddenly more than just the monster, and the person who had been the victim in the story was more than just a victim.

I can’t think of anybody who participated in that Council who wasn’t altered by the experience. And nobody forgave anybody. Nobody was fixed. Nobody was healed. Nothing was solved. But people walked away more compassionate. The empathy was palpable. I think it had to affect what they did next, and how they would tell the story to their children, and what would happen in the schools and the hospitals and maybe the parliament.

It was like we’d tilled the soil, and at the end of the five days we saw some green shoots.

Kight Witham: Part of the Council process is to show up empty-handed, with no preconceptions, as uncomfortable as that is.

Seide: And to cultivate in oneself a practice of being comfortable with silence, with listening and being present. Being able to sit with discomfort is a prerequisite for being a Council trainer.

Bernie Glassman talked about three tenets. The first is not knowing, which isn’t ignorance, but rather letting go of what you think you know. The second is bearing witness, which is critical to the practice of Council. Bearing witness means listening deeply, with, as the Buddhists say, “eighty thousand pores wide open.” The third tenet is that compassionate action arises from the first two. Our impulse is to fix and to rescue and to control, but to truly know what will serve in that moment, we must let go of all that and be present with what’s there. Then we can become powerful allies.

Kight Witham: I think of a TED talk by [Nigerian writer] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie about the danger of having only a single story about a person and not allowing different realities to exist. It makes me think of how we have a single story about people we lock away in our prisons: the offense that put them there. We don’t want to think about the children left parentless or the older parent who is now alone.

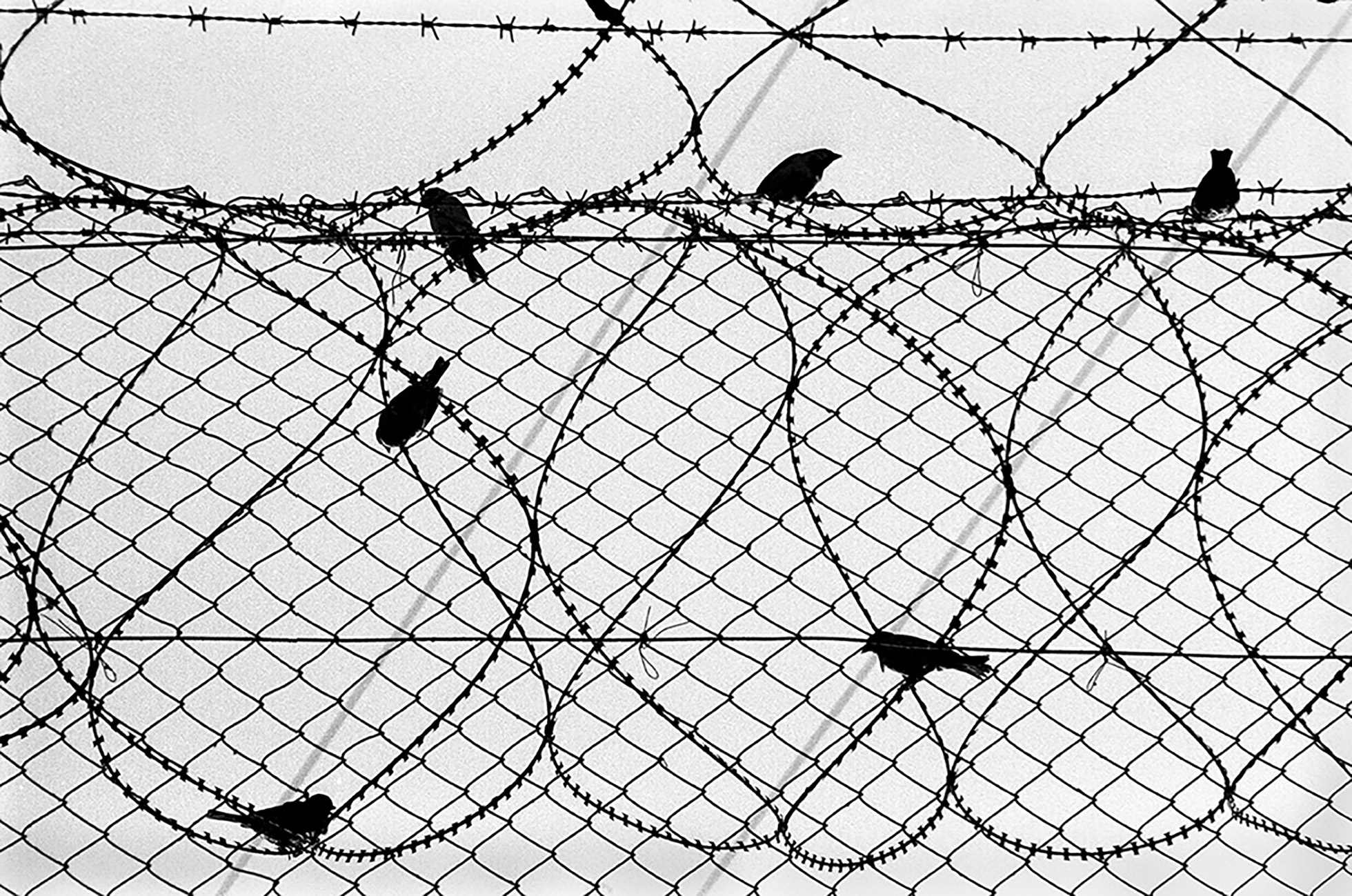

Seide: It’s the tyranny of the loss of nuance, of oversimplifying. The concrete prison by the freeway might look innocuous enough to those driving by, but it houses people who are suffering deeply, and whose family members are suffering. To be unconscious of the segments of the population we don’t want to see affects all of us. And it’s impossible to sustain that. Whether we are talking about incarceration or education or health care or any number of systems, we are damaging the next generation when we let people’s stories be lost and let folks become invisible.

Kight Witham: Tell me about Council circles in Soledad State Prison, also known as Correctional Training Facility.

Seide: Soledad is on the outskirts of Salinas, outside of San Francisco. Randy Grounds was warden there when we began to bring Council to those inmates, and he was someone who thought deeply about all this. After the state of California decided to make rehabilitation a priority, he and I had a conversation about what rehabilitation means.

The very concept of rehabilitation suggests that a prison system can encompass some progressive ideals. And Council can reinforce the idea that such transformation is possible, if incarceration is about more than locking people up and keeping them there and never hearing about their lives and their humanity. My feeling is, if I can find those officials like Randy who really want to put the rehabilitation back in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, I can tell them a story about the great work that is already happening.

Here’s an example: I sat with an inmate who was affiliated with a gang, and he was sitting in a circle and hearing a story from somebody who was in a rival gang. And the rival prisoner described how he had worked on forgiveness, and it had helped him find peace. When it came around to the first inmate, he said that he had never really thought about forgiveness until just then. And he thought about his mother and how he needed to ask her forgiveness. “Thank you for saying that,” he told the other man. “It changed my thinking.”

The next day I saw him schedule a phone call and actually reach out to his mom and tell her he couldn’t find peace unless she forgave him. He asked if she could find a way to forgive him for what he’d done to her life. That ripple had begun with a rival, an “enemy.” That man deepened and grew. He became heroic in that moment, doing something that hadn’t been possible for him before, all as a result of listening to somebody who, by the standards in place in that prison, he shouldn’t have listened to.

Whether we are talking about incarceration or education or health care or any number of systems, we are damaging the next generation when we let people’s stories be lost and let folks become invisible.

Kight Witham: That’s something that doesn’t happen every day.

In my experience, when you’re in a Council circle, you don’t have to say anything. You don’t have to add anything to people’s stories. You don’t have to give an answer. You don’t have to interpret it for them. You just get to listen.

Seide: Every encounter is different, and if we practice how to create a space where this kind of deep interaction is possible, then we get more skillful at applying it over time. We don’t use new-agey words with people who don’t talk that way, but we can create a ceremonial space with anyone who is open to it. We take five minutes when we get five minutes, and we take a couple of hours when that’s possible, and we don’t get stuck calling it by certain names or needing it to be surrounded by trappings that connote “spirituality.” Council is for all of us who are slowly losing touch with the ability to be present with each other. And maybe we can learn from those who have had the courage to show up with open hearts and leave behind old ideas of who they used to be, or think they should be, or who we are in their stories.

When I go into a prison, there’s often a moment when the officer at the entrance is looking through my backpack and asking, “What are you going to do with this? A seedpod? A shell? And what are you doing with the dog collar?” I have to justify each object I’m bringing in to use as a talking piece. So I explain that my dog Max wore this collar for years, and my daughter found the shell, and how all these objects are meaningful to me.

In a circle, when I’m sharing these items that are precious to me, the group starts to realize that, even though they are in prison and don’t have many belongings, there are objects in their cell that are precious, whether it’s a family photo or a ChapStick. One guy brought a sewing needle and a bit of thread to the circle, and people kind of snickered, but when it came time to tell his story, he spoke about how terrifying it had been for him to wind up in prison as a young man. (He was now in his late fifties or early sixties.) In his first week he had ripped his prison uniform, and his butt was showing. His cell-mate quickly helped him sew it up and said, “I’ve got your back.” And in that moment he felt that somebody cared. He’d kept that needle and the thread all these years. That act of generosity had remained with him.

People want to celebrate the things that symbolize generosity and goodness in their lives. To share that with others and have others understand that this means something to you — that’s an extraordinary act of communion. It seems so natural, but unless you’re reminded to take the time to enact that gesture, it doesn’t occur to us to do it. Our lives are not full of sacred spaces or ceremonial processes. We might go to church or temple, but we don’t often create sacred space for ourselves.

Kight Witham: What were some of those first prison Councils like?

Seide: I was invited to go in with a couple of nuns who were running a program at Correctional Training Facility in Soledad. There were guys in that circle who had sentences of 150 years to life. It was overwhelming and disconcerting for me to be sitting with these people, and when I got to speak, I had to admit how it was difficult for me. I’d never been in a prison before, and I’d been taught to be afraid of guys like these. And yet, hearing their stories, I felt that I knew them, and I trusted them, and I felt they really cared about my stories. I shared all of this, and the men and I were able to develop a rapport because of our commitment to authenticity. That first experience gave me a sense of being someone who lives with a great deal of privilege, just from having been born into the skin that I have, in the place where I was born. At the end of that hour and a half, I told them, I realized that I was going to go back to a hotel and would get to have a nice dinner, and they weren’t going anywhere. And I shared how that kind of broke my heart.

One man told an extraordinary story about wondering what a pomegranate tasted like. He’d read about the fruit and wondered what it smelled like, what it would be like to actually bite into one of those seeds and have it explode in his mouth. And I remember later walking by a Whole Foods and seeing a big stack of pomegranates and thinking, Can I just sneak one in to him? And then I thought, No, that’s not for me to do. I wasn’t there to smuggle pomegranates to somebody, to solve a problem. I was there to hear that story, to be heartbroken, and to enjoy the pomegranate I would eat on behalf of everybody who didn’t have that opportunity, and to feel the sadness of that — and then to come back and talk about it and be able to carry my privilege honestly, and maybe use it to build some bridges and create compassion, as someone who was able to walk between those two worlds.

People want to celebrate the things that symbolize generosity and goodness in their lives. To share that with others and have others understand that this means something to you — that’s an extraordinary act of communion.

Kight Witham: It must be hard to find common ground, with such different life experiences.

Seide: We’ve learned, as Council facilitators, that we need to find discussion prompts that are universal. I didn’t come in saying, “Let’s talk about a time we killed somebody,” but rather, “Let’s talk about a time we lost something,” or “a time we did something we regretted,” or “a time we got away with something.” We all have stories like that. So I was able to bring my authentic truth, which was no better or worse than anyone else’s. It was just my truth. I think they respected that I was not trying to hide my discomfort. Facilitating in Council is not as much leading as it is smoothing the way.

Those guys are particularly good at sensing authenticity and knowing what’s up, and to feel I had earned the ability to sit with them was a great honor to me. I also found myself identifying with them to the point that I started to resent some of the correctional officers. It took a couple of years for me to realize that everybody is suffering in a system that dehumanizes any of us. And when I started to listen to the stories of the correctional officers, I realized that I had fallen into “us versus them” thinking.

One of the most difficult prisons we were able to work in was Pelican Bay just after they ended administrative segregation, or AdSeg, which is pretty much solitary confinement. After decades men who’d been in AdSeg were being moved into the general prison population. I heard from them what it was like to spend years isolated from any human connection. I heard men talk about being brought out to get that phone call with the news that a mother or father had died. They had to have the phone held up to their ear because they were in shackles, and then they were led back to solitary with a hand on their shoulder pushing them forward as their only human contact. Afterward they had days, weeks, months, years to think about how they had failed their parents. Hearing that changed how I reacted when my own father was dying. I was able to set aside all of the bullshit and drama I’d had with my father, because I knew what a gift it was for a son just to sit with his dad. How many men in prison wished they could have been there, sitting with their dad? They’d mentored me in that moment of human tragedy. They’d taught me not to squander that opportunity.

Kight Witham: How does race come up in these prison settings? Do you find your own assumptions or biases being challenged?

Seide: For me, sitting across from a man with a swastika in the center of his forehead and seeing SS tattoos on people’s arms has been really triggering. It’s been a challenge, and a great revelation, to see beyond that into some beautiful, kind human beings. I’ve spoken about my Jewish heritage in the presence of Aryan Brotherhood members. I’ve seen how quickly the lines are drawn on day one of a Council group, and how quickly those lines dissolve when someone says, “I never thought I’d hear a story that would make me cry from someone who looked like you,” or, “I never realized that somebody who looked like my enemy could sound like my brother.” But relationships on the prison yard do not change as quickly as they do inside that Council circle. So how we navigate the transition from Council back into the world is critical. Some of the alliances and compassion that happen in Council need to be protected from what might await on an overtly segregated prison yard.

Still I think there are certain bells that can’t be unrung, certain things that are just undeniable, such as the way folks interact across races, across politics, across gang affiliations as a result of the bonding in the Council setting. Correctional officers and staff have observed changes in how people behave. It’s reducing the amount of violence and antagonism on the yard, where the culture of racism has been in place for decades. I’ve been very clear and direct about my own whiteness and privilege and maleness and economic status, and I’ve found it’s not as divisive as it might be. We all have our own stories of love, loss, fear, and joy, and I find that racial identification disappears as those stories come out and we reside in our authentic humanness.

The effectiveness of these Council programs is provable and replicable. We’ve reached out to academia, and we now have solid research to show that participating in a Council program will improve empathy, impulse control, and social attitudes. A lot of folks are skeptical of this touchy-feely, wishy-washy kind of “candles and sandals” work, but by testing for these things using academically validated scales, we have convinced them to give it a chance.

Kight Witham: You spoke about how, in Rwanda, a woman described horrific murder, and then someone spoke who had been there that night, committing murder. Have you done anything similar in the U.S., bringing the perpetrator of a crime and the family of the victim into the same space together?

Seide: In California prisons, victim-offender dialogue groups require an enormous amount of advance preparation. The moment has to be right. Surrogate victims are often more effective in these encounters — somebody who has been the victim of a similar crime, but not necessarily the victim of that specific crime, and has done some work on healing. Restorative justice needs to be thought of as systemic, not transactional; it needs to restore something. When a community is so full of acrimony that no one can sit with each other, there’s nothing to restore.

Although Council practice is not restorative justice per se, I think it’s a critical foundation for effective restorative-justice interventions. In Council we sometimes include an empty chair in the circle, a place for the person who is with us in our heart but not there in person. That provides an opportunity to invite into the circle those individuals who have been harmed by our actions. It lets us think about our own accountability and speak to the person who is not there. I have heard men say, “Man, I wish that person could be here. If they were, this is what I’d have to say to them.” When you speak the words that maybe you have never spoken but that are bubbling up in you, and a community of people you have come to trust are there to bear witness, I think it goes much deeper than going through the motions of writing an “I’m sorry” letter. It’s as if we’re rehearsing conversations that we’d like to see happen, though life might never give us an opportunity to have them. Maybe we figure out what it is we need to do to make amends or what we need to ask forgiveness for. Though it might not involve a direct dialogue with somebody, Council helps us focus on harm and accountability. It begins to move us toward empathy and is a critical step toward real rehabilitation, even redemption.

Kight Witham: Tell me about your work with police officers.

Seide: Council can help police officers cultivate positive relationships with the communities they serve, so that they can become real guardians of the community. But it starts with self-compassion. It starts with understanding how we respond to stress, what effective communication looks like, and how to create positive relationships. It’s much more proactive than “de-escalation training” [teaching officers to remain calm in crisis situations — Ed.], which I think is starting too far downstream. It’s too late when you get to the point in a crisis where someone feels the only option is to use force. Officers need to learn to recognize and manage their potentially detrimental responses to stress as they arise. And Council lets them practice that with others whom they trust.

It’s important to recognize, first, how the system often sucks the life out of law-enforcement officers. The stress of the job results in sickness, depression, anxiety, suicides. The average age of death for people in law enforcement is fifty-seven years old. When you join the force, you are potentially giving up your retirement and your ability to see your grandchildren grow up, because of stress-related illness and maladaptive behaviors like drinking, addiction, violence, hypersexuality — so many things that cops get caught up in as a way to manage stress. The job creates a habit of hypervigilance that they can’t shake. They don’t know how to leave work at work, and they’re constantly afraid something’s about to blow up around any corner. When they get off shift and it’s time to coach soccer or take their kid to Pizza Hut, they are still carrying that stress. Some might attack a person who taps them on the shoulder, and then not understand where that rage came from. They are not taught effective ways to de-escalate; to recognize and regulate their stress; to work skillfully with tense moments and not just pull out their gun. Sometimes in the line of duty pulling a gun is the right thing to do, but not always. Teaching skills to navigate these moments can save lives in the moment of crisis, as well as teach us how to be a healthier human.

It’s been extraordinary to see law-enforcement officers open up to this process. Some are starving for it. Didactic, presentational methods of training officers are ineffectual. Behavioral science has shown us that immersive, interactive, long-term, practice-based education is the way we learn best.

So we start with self-awareness and self-regulation. Then communication and relationship skills. Then meeting the community. We have a program called Cops and Communities Circling Up that’s trying to bridge the divide between the police and community organizations and activists. I’d say the skills that Council teaches generally come easier to nonprofit and social-justice workers than they do to correctional officers and cops. But everyone can recognize stress and how it can throw us off our game.

The officers I’ve worked with really want to meet members of the community in Council; to see not just the Black Lives Matter placards but the individuals holding them. They want to hear those people’s stories. We can talk about policy and politics later. First let’s talk about how it is to be a human being, to be someone’s son or daughter or father or mother.

Kight Witham: What law-enforcement agencies do you currently work with?

Seide: We started with the Los Angeles Police Department and the Bureau of Prisons. We initially chose to go deep with two specific groups: the LAPD South Division, and the Bureau of Prisons Metropolitan Detention Center downtown. The stories of what we did there spread, and the director of training at the LAPD came to us and said they wanted to offer this throughout the department. As agencies are hearing about this work we’ve started in Southern California, we’re getting calls from all over the country, which is very exciting. C-POST [the state certification agency] has approved professional credit for officers who take our course. There’s a cultural shift that needs to happen in the profession. I think we’re seeing the first stirrings of that. I attended an officer-wellness symposium for police chiefs in Miami last February that had four times as many attendees as the year before.

We’ve learned to do some things differently when introducing Council to police officers. We don’t need to be quite so ceremonial. The idea of a huddle goes over pretty well: a forty-five-minute Council where folks can sit and take a breath, check in and reflect before they “armor up,” put on the Kevlar to go out on the street. We call the program POWER Training — Peace Officer Wellness, Empathy, and Resilience.

Kight Witham: Tell me about the start of the police program. When did it begin to flourish?

Seide: On the first day I met with twenty-five LAPD officers, all of whom showed up to our training with an enormous amount of skepticism. It was a mix of young officers and veterans. Probably all of them had their arms crossed and their eyebrows raised, if they weren’t outright sneering. There was not a lot of love. They had been preached at over and over by people who thought they knew better, who thought they could do the job better, who thought they had insight that only someone who had a psychology degree could possibly have.

Kight Witham: So it was a tough room.

Seide: It was a tough room. It was a tough day. At the end of it my partner left with his shirt drenched with sweat, feeling like he couldn’t come back, which was totally understandable. But I saw a glimmer of something. Day two started differently. People had taken some of our suggestions about breathing techniques for getting to sleep and other exercises we’d done. Some of the veterans remarked that, had they known about these techniques earlier in their career, they would not have been in the state of ill health they were in now: the stress, the blood-pressure medication.

Some of the younger officers opened up in our Council about how difficult it was to have this conversation, when the norm was just to button up and keep uncomfortable topics to yourself. Vulnerability was seen as weakness. We posed [author] Brené Brown’s question: “Is there any act of courage that you have known to exist without some vulnerability?” Nobody could think of any. Courageous action requires vulnerability. By the afternoon things had started to come out that were remarkable, goose-bump inducing. People were choking up, beginning to feel emotions they had been holding back, and in some cases they spoke beautifully about them.

At the end of the session a lieutenant told me there were people in that room who had talked more that day than they had in the last five years he’d worked with them. He could see how they were carrying so much. Later he told his superiors he wanted his entire unit of sixty officers to get Council training right away. When things got tense, he wanted everyone in the room to be able to break into this practice together. Now, a few times a week, his whole unit stops everything and huddles up in Council. The understanding of stress is growing, and the communication is much easier.

Obviously if we’re going to change police culture, a lot more needs to happen. But we’ve made amazing inroads in a short amount of time. Folks in these programs are sleeping better. Colleagues are telling them they look healthier. Their kids want to hang out with them. I feel like these officers are better able to work with the community because of these skills they’ve started developing in themselves.

Kight Witham: But does feeling healthier change how they behave?

Seide: Joan Halifax [founder of the Ojai Foundation] says that you can’t teach compassion, but there are ways you can prime the pump for compassion to emerge. We know what feels healthy and wholesome, and we can train people in best practices. There’s an innate human goodness that shows up when our newborn is laid on our chest, or when we see somebody in pain. Everyone has the capacity to care. And sometimes it just gets blocked. We become hardened when we’ve been hurt. There are police officers who really do care but who don’t know how to access that when walking into a tough situation. I think it all starts with how we understand the stress and resistance we encounter and the ways we can deal with that and regulate ourselves effectively. A chief in LA South Bureau has told me that sometimes his officers just break down in his office, and he doesn’t know what to say. He told me he wished he could help them build skills so that they don’t collapse, or have a nervous breakdown, or harden themselves, or just leave the force. I think that’s what our programs and the ongoing Council huddles do.

Officers are taught in the academy that they have to control chaotic situations. If something is out of control and dangerous, we want them to be in control, but sometimes the control winds up being oppressive and harmful. When the use of force comes into play, it can be tragic. On the other hand, if a situation is starting to spin out, and somebody is posing an immediate danger to innocents, you can’t say, “I need some space. Let’s all take a breath and light a candle and close our eyes.”

I remember [police officer and peace activist] Cheri Maples asking Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, “Can I do this work? How can I be open to all these teachings that you have and carry a gun?” And his response was “Who would you rather carry a gun than someone who has a meditation practice?”

Good decisive action comes from a place of compassion, not misunderstanding or fear or prejudice. Sometimes we need to act decisively in the moment, and if it’s done in a heartfelt way, it can be beneficial to the community. In a difficult situation I’d rather have somebody handle it who is coming from a place of profound, and sometimes fierce, compassion.

It’s critical that we look for ways to rehumanize our systems, and criminal justice, education, health care, and politics are all systems that can suck the humanity out of people. I think there is a great opportunity to reintroduce contemplative practices that remind us of who we really are. These practices not only benefit our individual and communal health, they enable us to perform better. It’s such an asset to know how to really listen to ourselves, to each other, and to the planet, rather than blindly following what our systems have convinced us is expected.

Kight Witham: The Sun recently ran an interview with sociologist Alex S. Vitale, who’s an expert in policing. He said that efforts to eliminate bias in policing have failed because of this entrenched culture of “us versus them.” How can Council make a difference?

Seide: Council is not a magic potion that makes everybody love each other. We believe you need to start bonding within groups you trust before you can bridge the divides between them. And trust is built on shared experience and vulnerability. The core of our approach is understanding that your identity is more than the role you’re playing; that in addition to being a police officer, you may be a parent, and you’re certainly a son or daughter. You’re a person who has a hobby, a person who fell in love once, a person who loves a certain kind of pizza, a person who laughs at good jokes. When you can bring that part of you out among colleagues, a spaciousness develops. You are able to work with more of yourself, not just your tactical skills. Those are important, of course, but you have so many more resources you can bring to bear.

Developing a broader sense of who I am and who my colleagues are opens space for relationships with others outside of my group, who maybe also had a Chihuahua growing up, or an auntie who made sweet-potato pie, or a mom with dementia, or an unrequited love they still think about. We uncover those commonalities when we sit together in Council. And the connections exist not just with your fellow officers but also with people you used to think of only as activists, as “Black Lives Matter people,” or as ex-felons. To see that, you must develop the capacity to listen beyond your idea of who someone is and what you are expecting them to say. But I would never invite people with an antagonistic relationship into a Council out of the blue and expect them to really listen to one another right away, amid the fear and resistance and suspicion.

If I’m a police officer, and I know you only as the activist who’s shouting, “Black lives matter!” at me, I probably can’t hear your story, and I believe you don’t want to hear my story, so we have nothing to talk about. But if I practice Council with my fellow officers, with my buddies, with my family, with people I trust and feel good about, and I know that you, the activist, have been practicing the same way, it might open up an opportunity for us to listen to one another and realize we are more than just the conflictual roles we play in public. We’re also part of the evolving human story.

I think about a moment when a pretty uptight police officer told the circle about his pet bunny, and something shifted. He felt comfortable enough to bring that story forward because he had practiced Council, and others in the community felt comfortable enough to listen to him, and not just write him off as an uptight, unfeeling officer, because they had practiced.

Kight Witham: It seems like it would be hard to get people to view with compassion someone who’s been oppressing them.

Seide: That’s why we don’t start there. We start with the notion of self-care: How do my shoulders feel right now? How am I sleeping at night? What’s my appetite like? How are my conversations? That self-awareness is the first step. Then we ask: How do I take care of myself so I’m not so stressed out? So I’m not walking around with my shoulders at my ears because I’m so tense? Once people have tried Council, they might think: Maybe, when I go home, I can practice this with my kid and my spouse, so that I can be more present for them. And maybe at work I can really see my colleagues and appreciate them.

We cultivate this facility for compassion in a safe way, until it’s a skill that can be brought to the community. At that point people realize it’s critical not just for their own well-being, but for the well-being of generations to follow. If we don’t understand the importance of that person sitting across from us in the circle, then we’re not seeing the full picture. But we can’t begin there. We need to aspire to that. We need to earn that. Some folks don’t want to hear that this is a slow process. They want a quick fix. But it’s a complex, wicked problem. To solve it takes time and commitment. And I believe the solution arises from authentic presence and connection.

I remember reading a Sun interview with Bruce K. Alexander, who is renowned for studying addiction with an experiment called Rat Park. He showed that rats who were fed morphine in isolation became addicted, while those who could be social didn’t want the morphine. That’s so important to remember. The way we behave when we are feeling isolated and dislocated and disconnected is different from the way we behave when we have a sense of connection and community. Societal ills are exacerbated by a sense of being “siloed.”

There’s an innate human goodness that shows up when our newborn is laid on our chest, or when we see somebody in pain. Everyone has the capacity to care. And sometimes it just gets blocked. We become hardened when we’ve been hurt.

Kight Witham: You’ve said Council isn’t about “fixing” people. Doctors see fixing people as part of their job. Tell me about your work with health-care professionals.

Seide: The health-care system is not only dehumanizing; it’s killing folks. The suicide rate among physicians has doubled. I’ve read that more than 50 percent of doctors report being burned out, and 70 percent would not recommend a career in medicine to their children.

This is one of those problems that can’t be addressed with a top-down solution. Yes, people are navigating it, but what toll is it taking? If you’re a doctor, patients are facing life-and-death situations and looking to you for solutions. What if there is no solution, or if you are unsure? How do you handle that and keep yourself whole? How do you keep your heart open and not just become a puddle at the end of every encounter, let alone every day? We’re teaching health-care professionals to create a place where they can let go of everything they think they have to be for everyone else and attune themselves to what’s alive in them and in their relationships. They are responding to an incredibly stressful job, and they need some way to regulate that stress, to get through the day so that they don’t feel like hell and are able to sleep at night and to have a relationship with their kids and their spouse. Like cops, doctors learn to cover over stress with a steely demeanor, but that’s not a healthy situation. They need a safe place to work on this.

Kight Witham: We’ve talked a lot about your work with prisoners. I can imagine somebody in prison reading this and wanting to practice in a prison setting, without any training, without a program from outside. What would you tell that person?

Seide: Anybody who is reading the words that you and I are speaking now and who feels these words resonate is already moving toward the circle. I hope there will be increasing support for these programs in prisons. But opportunities to practice in person may well be limited by our circumstances. Those who sit in AdSeg and have one hour a day of pacing around a small space can’t come together with their peers, or anyone. Others may not have a group to go to, but there are many opportunities to be present with every moment, to speak in a way that’s alive, to listen beyond what we think we’re hearing, to see beyond the person we think is in front of us.

When cell-mates turn away from a conversation that is transactional or competitive and toward an intention to create a deeper understanding, the spark of Council is alive. When incarcerated folks are visited by families, and the interaction shifts to take in the big picture, whether they sit in an actual circle or not, that can be Council.

Amazingly, as a result of the current pandemic, we’ve seen the emergence of effective virtual gatherings in our community programs. We’re offering “Social Connection Councils” online to essential workers, like doctors and nurses, as well as to the general public, and I’m surprised it’s been so powerful and effective. That moment of feeling truly seen, if only on a screen, is nourishing.

Of course, we’ll be back to gathering in person at some point. Hopefully there will be more opportunities for folks to practice in groups, with a bunch of chairs in a circle and a space at the center and a little peace and quiet. We are restored by connecting with one another, by showing up and sharing our stories. Whether it happens in a circle with a talking piece or not, it’s a deep longing we’ve all felt: to listen and to be heard.