Christian conservatives’ support for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan is well publicized, but there is also a long tradition in the U.S. of Christians using nonviolent direct action to oppose militarism. One of the current leaders of that nonviolent resistance is John Dear, a Jesuit priest who has been arrested more than seventy-five times for civil disobedience. For him, to be a Christian is to question the government and reject violence in all its forms. In his recently released autobiography, A Persistent Peace: One Man’s Struggle for a Nonviolent World (Loyola Press), Dear writes, “The arrival of dawn comes at a high price. It requires good people to break bad laws.”

Born in North Carolina in 1959, Dear has committed civil disobedience at the U.S. military’s School of the Americas (since renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation) and has broken the law to protest nuclear-weapons development at sites such as the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory and the Nevada Test Site. On December 7, 1993, he was arrested at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in Goldsboro, North Carolina, for hammering on an F-15 nuclear bomber. It was one of a series of protests, called “Plowshares Disarmament Actions,” inspired by the biblical prophet Isaiah’s prediction that the nations of the earth will “beat their swords into plowshares.” For that action Dear spent more than eight months in a North Carolina jail with fellow Catholic activist Philip Berrigan.

Dear has spread his message by giving hundreds of lectures on nonviolence in the U.S. He’s also traveled internationally to witness the violence perpetuated by U.S. policies and military actions in Guatemala, Nicaragua, Haiti, the Middle East, Colombia, and the Philippines. In the early 1980s he lived and worked in a refugee camp in El Salvador, and in 1999 he led a delegation of Nobel Peace Prize winners to Iraq to witness the deadly effects of UN economic sanctions on children there.

In the late nineties Dear served as the executive director of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the largest interfaith peace organization in the U.S. After the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center, he helped coordinate the chaplain program at the Red Cross’s Family Assistance Center, working with hundreds of firefighters and police officers, as well as with family members who’d lost loved ones.

Dear was vocal in his opposition to U.S. military retaliation for the 9/11 attacks, and his antiwar position got him kicked out of his New York parish by his Jesuit superiors. He moved to northeastern New Mexico to serve as pastor for several parishes there and later cofounded Pax Christi New Mexico (www.paxchristinewmexico.org). In 2008 Dear was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa.

In addition to his autobiography (www.persistentpeace.com), Dear is the author or editor of twenty-four books, including Put Down Your Sword: Answering the Gospel Call to Creative Nonviolence (Wm. B. Eerdmans), Living Peace: A Spirituality of Contemplation and Action (Image), and The God of Peace: Toward a Theology of Nonviolence (Wipf & Stock). He writes a weekly column for the National Catholic Reporter at www.ncronline.org and is the subject of the film The Narrow Path. Dear advocates vegetarianism as a form of Christian nonviolence and has worked to end the death penalty. Currently he is coordinating a nonviolent campaign to close the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

While interviewing Dear, I heard in his voice an inspired perseverance and deep commitment to working for peace and justice. When I talked with him again recently, he explained that he was rather busy: he’d been arrested the previous day during protests at Nevada’s Creech Air Force Base, the center for U.S. drone warplanes, and he’d just gotten out of jail. He added, “And tomorrow I plan on going back and getting arrested again.” He is currently awaiting trial for his Nevada protests against U.S. military activities.

JOHN DEAR

Malkin: You’ve said, “Nonviolence is not passive.” Can you elaborate?

Dear: Everyone presumes pacifism means passivity, that the only response to violence is to either retaliate or do nothing. Nonviolence is a third choice, and an active one. For me, nonviolence is not just a tactic or a strategy; it’s a way of life that requires us to love our enemies. It demands creativity, initiative, and engagement with the culture. There’s nothing passive about it.

Labor leader César Chávez said to me long ago that we can’t be nonviolent by sitting alone in our rooms and praying the rosary. Nonviolence happens in the world, usually on the streets. Yes, nonviolence requires private prayer, but it always leads to public activity and risk. Gandhi defined nonviolence as “conscious suffering.” He said it is practiced only in courtrooms and jail cells — and on the gallows, because true nonviolence means being willing to give our lives for lasting justice and peace.

Malkin: Tell me about your experience with breaking the law to protest injustice.

Dear: I’m still learning from and reflecting on all of the experiences I’ve had. I think that living responsibly in the United States requires resistance to the culture of war and injustice.

When I was a college kid at Duke University, I decided to give my whole life to God and become a Jesuit. My parents were appalled and begged me not to, so I agreed to wait for a while. I decided to hitchhike through Israel first, make a pilgrimage to see where Jesus lived. I was there when Israel invaded Lebanon in the summer of 1982. I saw the jets swoop down over the Sea of Galilee and bomb the place where Jesus had said, “Love your enemies.” That was a great revelation. After that I entered the Jesuits.

As a young Jesuit I wrote to Daniel Berrigan and his brother Philip, who were icons of the peace movement. Dan is the one who told me that change happens when good people break bad laws and accept the consequences. It’s been true throughout history, whether you look at the abolitionists, the suffragists, the labor movement, the civil-rights movement, or the antiwar movement. Dan also said to me, “If you’re going to follow Jesus, making trouble for peace is just part of the job description. Look at Jesus: he got killed.”

I immediately went and got arrested at the Pentagon. I tried to get a few friends to join me, but they wouldn’t. I was twenty-two years old and almost got kicked out of the Jesuits, but a higher-up let me stay. That was the first in a series of arrests for me all over the country.

Malkin: In 1993 you participated in a Plowshares action in North Carolina with Philip Berrigan.

Dear: Phil and two friends and I went onto the Seymour Johnson Air Force Base and hammered on an F-15 nuclear-capable fighter-bomber, which was on alert to bomb Bosnia. It wasn’t the first time anyone had done something like this. Ours was about the fiftieth of the Plowshares Disarmament Actions. We were convicted of two felony charges: destruction of government property and conspiracy to commit a felony crime. I faced more than twenty years in prison and fully expected to get five. In the end Phil and I did about eight and a half months together in a tiny North Carolina jail cell. Then the judge at my sentencing put me under house arrest for nearly a year. And after that I was on probation. Even now, I’m still monitored.

Malkin: There are differing views in the social-justice movement on how useful it is to break laws and go to jail. Some think we can do more by remaining out of jail and agitating for political change.

Dear: I’m beyond the question of what difference it makes or whether a protest is successful. I’ve tried letter writing and prayer services. I’ve written twenty-five books, spoken to millions of people, held press conferences, and met with every politician I could. Gandhi said that after you’ve tried everything you can, you have to cross the line and break the laws that legalize mass murder in your name — and accept the consequences.

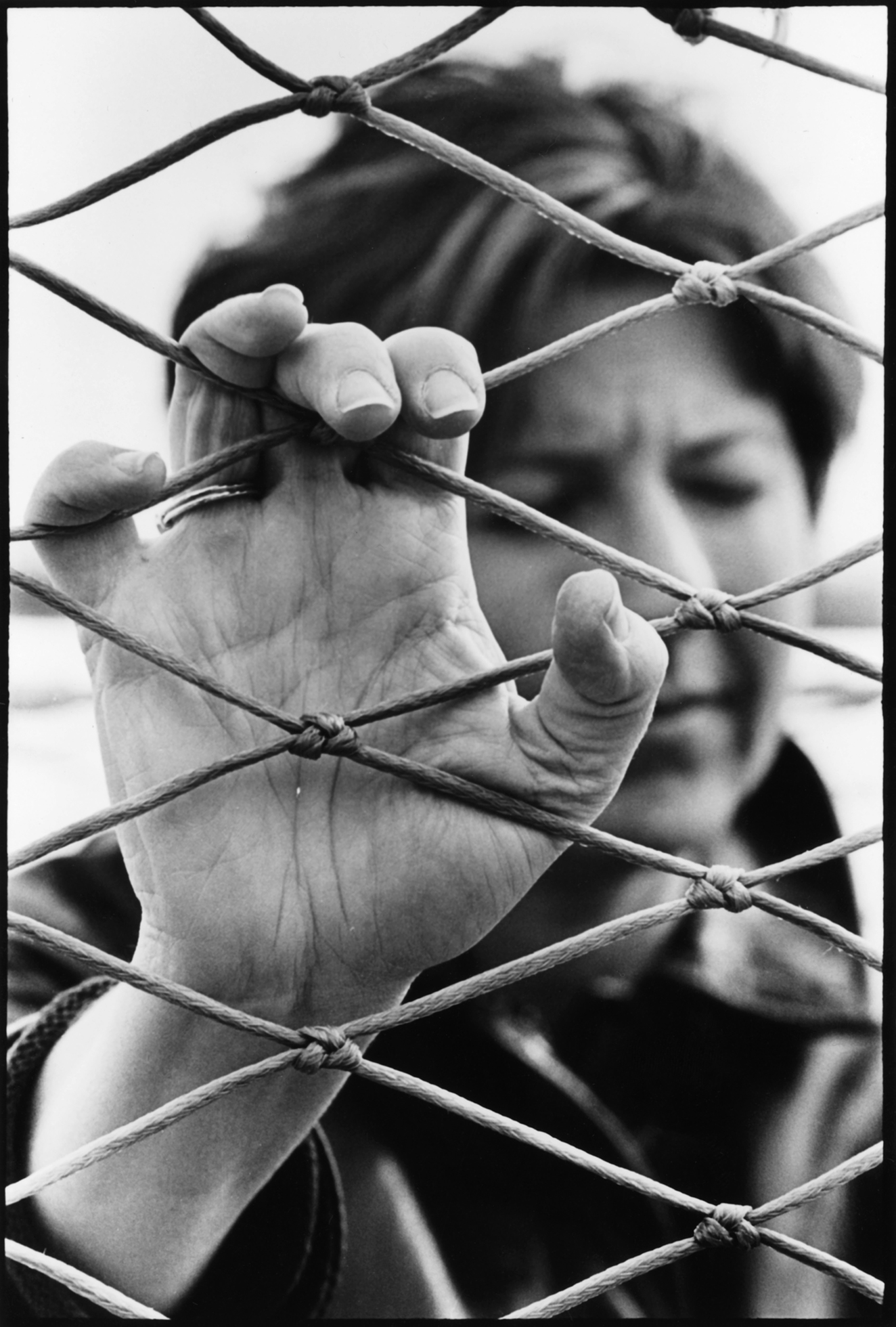

I’ll never forget being in that tiny jail cell with Philip Berrigan, feeling as if the walls were closing in on me. It was horrible. There was nothing romantic about it.

Malkin: You’ve also said that you had profound spiritual experiences in jail. What kind of spiritual growth or clarity did you find there?

Dear: I’m still trying to figure it all out. I actually never made it to a prison where you could go outside and walk around a yard. Phil and I were in a cell about eight feet by eight feet, with a bunk bed and a cold concrete floor. There was an open toilet, and our food came through a slot in the door. It was like being locked in a bathroom. We didn’t know how long we were going to be in that cell. The warden was afraid to put us in the general prison population, so he kept us isolated. The only time we got to leave our cell was when we were brought into a little hallway. It was even hard to pray in jail, because Phil and I were always together. As a Jesuit priest I’m used to having solitude, privacy, and silence. Not knowing what was going to happen — and not even being able to walk around — quickly had its effect on us. It was a kind of low-grade torture.

Malkin: What was a day in jail like?

Dear: We’d get up at 6 A.M. and read about five or ten verses from the Gospel of Mark and then talk about them for two or three hours. I learned more in that eight months than I had in four years of graduate theological studies at Berkeley. The Scriptures took on a whole different meaning. Then we’d take a little Wonder Bread from breakfast and break bread. Every Monday we were given a plastic cup of grape juice, and we’d hide it in the toilet and let it ferment. We’d break the bread and pass the cup and have Eucharist. It felt as if God was right there in the cell with us, in our suffering, loneliness, and claustrophobia.

Despite all of that, there were moments of profound peace and deep joy, which makes sense to me now: if you do the will of God — and working nonviolently for an end to war and nuclear weapons is God’s work — then God will touch you. That’s what the lives of saints and mystics tell us. Being in jail was painful, and it was a profound mystical experience. We were getting a small taste of the suffering of all people in prison and of the poor. There’s a lot of talk among Jesuits about how to be in solidarity with the poor. I’m a white male priest, and I’m rich compared to most people around the world. Going to jail is one way for me to know their suffering. It’s probably the closest I can get in this society. Jail was a spiritual journey of downward mobility.

Malkin: You’re just now coming off six months of probation, right?

Dear: Yes, in September 2006 some friends and I helped organize the Declaration of Peace, which was a direct action at 350 Congressional Representatives’ local offices. I was part of a group of nine who went into the federal building in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and headed for the third-floor office of Senator Pete Domenici, one of the biggest Congressional hawks, who brings funding to Los Alamos for nuclear weapons. We wanted to give him a copy of the Declaration of Peace and ask him to work to end this evil war on the people of Iraq. As soon as we stepped into the elevator, the police charged us and wouldn’t let us go up or get out of the elevator. We said we were there to see our senator, and we weren’t leaving. I had brought with me the names of ten thousand Iraqi civilians killed and of every U.S. soldier killed. We started to read them out loud there in the lobby of the federal building, through the open doors of the elevator. We did this for seven hours. Meanwhile they brought in the SWAT team, the FBI, and the head of Homeland Security for the state. Finally they arrested us all on federal charges. I think they deliberately went after me because of my work to close Los Alamos. We were in and out of court for a year and were found guilty of a federal misdemeanor. I expected to get six months in prison but was given a very strict federal probation instead.

Malkin: That brings to mind a story in your book about the Plowshares trial in North Carolina, when the judge asked who had driven you to the air-force base.

Dear: The moment you’re referring to was actually at Philip Berrigan’s trial in April 1994 — they gave us separate trials. There was enormous publicity, and the place was packed. Phil had called me as a witness, and I was brought into the courtroom in chains and an orange jumpsuit. All the jury members worked at the air-force base, and the prosecutor worked with the air force, too. They were trying to uncover the identity of our key support person — who, unbeknownst to them, was sitting in the front row — so they could arrest him, too.

After I testified about Phil, the prosecutor asked, “Who drove you that day to the Seymour Johnson Air Force Base?” I refused to name anybody, saying, “I take responsibility for my own actions.” The judge grew angry and ordered the jury out and said if I didn’t answer, I’d get two years in prison for contempt of court. I said, “OK, I’ll answer.” They were all shocked that I’d agreed so quickly. They brought the jury back, and the prosecutor asked me the question again, and I said, “Thank you for pushing me to tell the truth. The truth is that we were driven to the Seymour Johnson Air Force Base by the Holy Spirit.” The judge started yelling and hammering his gavel. He struck my testimony from the record, ordered me out, and dismissed the court for the day. It was a great moment.

Malkin: You were in New York City when the attacks of September 11, 2001, occurred, and you volunteered to serve as a chaplain to rescuers and families of victims. You also spoke out against retaliation.

Dear: Yes, I was working at the Red Cross’s Family Assistance Center and also organizing against the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan. There was a story in the New York Times about my speaking out, and the Jesuits saw it and called me in and said I had to leave my position in New York within three months. I could go anywhere I wanted. So in 2002 I moved to New Mexico, where I am now.

Malkin: Why New Mexico?

Dear: It’s an incredibly beautiful state, and it’s the poorest state in the country, according to the 2000 census. It’s number one in military spending and number one in nuclear weapons. It’s also number one in drunk driving, domestic violence, and suicide. There are more millionaires per capita in Los Alamos than in any other place on the planet, because George W. Bush poured billions of dollars into it to build a whole new generation of nuclear weapons.

My hope when I came here was to take a small parish among the disenfranchised, just to serve them. The Church gave me five parishes and four missions, spread over a 150-mile radius, so I was working nonstop. Then the war in Iraq started, and I had to speak out about the injustice and the lies. I’d been to Iraq and spent three hours with Iraqi deputy prime minister Tariq Aziz. I knew that good, innocent people would die in this war.

But this viewpoint didn’t go over well in New Mexico, which is a very pro-military state. The military heavily recruits the poor here; some of the poorest people in the country are Hispanics in the desert Southwest. My parishioners had no healthcare, no jobs, and no opportunities, and the high-school seniors in my parishes were getting letters every week from various branches of the military.

There was a lot of hostility toward me because of my opposition to the war. My wealthiest parish kicked me out. Then in November 2004 I woke up at six in the morning at the rectory in a village in the bleak northeastern corner of the state, and I heard soldiers marching down the street. The 515th Battalion of the New Mexico National Guard, which was leaving for Iraq the following week, was marching and chanting, “Swing your gun from left to right; you can kill those guys all night.” The whole town was awakened by the yelling. I got up and had coffee and felt sad and began praying about it. This went on for an hour. Then, at seven o’clock, the noise got really loud. I looked out the window and saw seventy-five soldiers right at my front door, shouting at the top of their lungs, “Kill, kill, kill!” These were just poor kids.

I’d lived in Guatemala at one time and had seen soldiers march down the street and terrorize people like that, but this was in the U.S. Here was a state military unit trying to intimidate a private citizen. It went against everything in the Constitution. It was the Wild West.

I was looking out the window and thinking, I don’t want to do their funerals. If you really want to know what it’s like to be a priest among the poor in New Mexico, I’ll tell you: you do funerals every day, because when the poor get sick, they just die, and because so many of them were serving in Iraq.

My job as a pastor was to protect these boys from the forces of evil, so I had to do something. I put on my coat and went out in the street and put my hand up. They all got quiet. And I said, “In the name of the God of peace, I order you to quit the military. I order you, in the name of the nonviolent Jesus, not to kill anyone and not to be killed, because God does not bless war. No war is justified. God thinks all war is evil and calls us to love our enemies. So stop all of this nonsense and go home. God bless you.”

They looked at me in stunned silence for five seconds. Then they burst out laughing and walked away.

All those kids were sent to Iraq, but none of them was killed.

We can’t be nonviolent by sitting alone in our rooms and praying the rosary. Nonviolence happens in the world, usually on the streets.

Malkin: Many conservative U.S. Christians support the military actions of the U.S. government. How do you reconcile that with Jesus’s message of peace?

Dear: For the record, I don’t believe you can be a Christian and support war in any form — or, for that matter, support greed that leads to global poverty or any form of injustice, racism, or sexism. Christians are supposed to be peacemakers. The only thing you can say for sure about Jesus is that he was nonviolent. That was his whole message. Martin Luther King Jr. said that this is actually the most exciting era for a Christian to be alive, because we’re at the brink of destruction, and our only choice is to lead humanity back to the nonviolence of Jesus. Gandhi said that Jesus was the most active practitioner of nonviolence in the history of the world, and the only people who don’t see that are Christians. It’s incredible!

There is a reason for it, though. The history of the Christian Church is one long rejection of the Gospels. For the first three centuries, under the Roman Empire, anyone who was baptized a follower of Jesus could not join the Roman Army or say that the emperor was God. That’s why so many of the early Christians were martyred. Others were scared to be baptized and waited until they were near death. Then the emperor Constantine I became a Christian and ended the persecution, but he also ended three hundred years of nonviolence in the Church. That set the stage for Augustine, the Church father who came up with the conditions under which Christians were justified in killing. Eventually we came to the “just-war” theory, and then the holy wars and crusades in which millions were killed or died in the name of Jesus. And today at Los Alamos a Catholic priest blesses all the Catholics who are building the nuclear bombs. There’s not much difference between past and present.

Malkin: Some activists say that it’s a privileged point of view to advocate nonviolence as the best strategy for everyone, including people who are suffering under U.S. imperialism. Gandhi taught that force may be used for protection in certain situations. Is nonviolence always the best strategy?

Dear: I’m not preaching nonviolence around the world. I am preaching nonviolence in the U.S., first and foremost to Christians, because we’re the problem. We are the ones who need to be converted.

When I was twenty-three and twenty-four, I lived in El Salvador and worked in a refugee camp with Jesuits who were later assassinated by the Salvadoran military, which had ties to the CIA. My desire at the time was to leave the United States, because it was so evil in my mind, but the Jesuits in El Salvador — the ones who were later killed — told me to go back and work in the U.S. to spread peace and stop the U.S. war machine from killing the poor around the world. While I was in El Salvador, the U.S. was organizing, supplying, and overseeing the bombing of that country, and the U.S.-backed “death squads” would come into the camp. I could go out and talk to them, because I knew they wouldn’t open fire on a white North American.

I also lived for a year in Northern Ireland in the 1990s, and I met with Gerry Adams, president of Sinn Fein, and members of the Irish Republican Army. They had heard about me through friends and were amazed that a priest would be willing to face twenty years in prison for hammering on a nuclear bomber. Because I had resisted the United States government, many people in Northern Ireland were willing to hear me out on nonviolence. Gerry Adams started reading my books. I think it was puzzling to him that I was willing to lay down my own life but didn’t believe in killing.

But I didn’t go there to preach. I was there to learn and listen. It’s here in the U.S. where I am actively trying to convert people to nonviolence.

I’ve been trying to celebrate life with the same intensity that I resist the culture of death.

Malkin: In spiritual practice we often let go and surrender to God’s will. In political action we actively try to change the world. How do you decide when to push forward and when to let go?

Dear: I don’t know exactly what you mean by “surrender.” In a way my whole life is surrendering to the God of peace. That’s why I became a Jesuit. I still have that desire. The only way to stay faithful is through prayer, friends, community, and periodic public action. Deciding when to do what just comes down to discernment and staying nonviolent and following the light that guides us to the next step of the journey. It’s a matter of faith and timing and having my eyes open to what’s happening in the world.

Right now I’m working on the next public action at Los Alamos. We’re bringing in some Nobel Peace Prize winners to call for disarmament. That just seems to be what I should be doing right now: standing up publicly and saying we have to get rid of nuclear weapons. It’s going to get me in trouble, but I believe it’s God’s work.

Likewise, there are times when I lean more toward reflection and retreat. For example, when I was under house arrest for ten months, I spent most of that time writing a book about my time in jail. I also used the time to reflect, let go of my need to control, and pray.

Malkin: Speaking of letting go, you’ve written that you loved music as a young person but decided to give it up because music wouldn’t fit with a path dedicated to peace and justice.

Dear: In college I was a serious musician. I minored in music and started a singing group at Duke University that continues today. I was writing and recording my own songs and wanted to be a rock star.

When I entered the Jesuits, I thought I had to renounce all that. Actually I didn’t have to give it up, but I was a kid and didn’t think you could be both a Christian peacemaker and a musician. It was all or nothing to me, so I left music behind and threw myself into the peace-and-justice movement.

One of my heroes was rock musician Jackson Browne. I’ll never forget sitting in jail in 1989 in Los Angeles for a day, after a protest to draw attention to the assassination of my Jesuit friends in El Salvador. A huge crowd of people were jailed, and I was moving among them when suddenly there was Jackson Browne. He said to me, “This is my church.” So I was wrong about music and peacemaking not mixing.

In these last ten years I’ve brought music back into my life, because it feeds my spirit. I’ve been trying to celebrate life with the same intensity that I resist the culture of death. Gandhi said that art, music, and literature need to be a part of every movement. Certainly music was at the heart of the civil-rights movement. We need art to give us soul and deepen our spiritual lives.

Malkin: There are some Christians who say that Jesus was greater than any human and that it’s not possible for us to live up to his example.

Dear: I’ve heard that many times. I’ve just come home from traveling the nation for two and a half months. I spoke to ten thousand people and told them all that if you’re going to follow Jesus, you have to be a person of peace, nonviolence, and love. And everywhere I’ve gone, some people have told me I’m wrong.

For me it all comes down to the four Gospels. They’re not a story of a holy being who made everybody feel good and loved. Yes, there were times when people were healed by Jesus’s presence, but he was trouble everywhere he went. He connected with all the wrong people and said all the wrong things. He hung out with the poor and marginalized. He touched lepers. He supported women’s rights. And then he turned and marched into Jerusalem, to the source of the problem, where the religious authorities were working with the empire to steal from the people in the name of God. He turned over the tables of the money changers.

If you march into the outpost of a brutal empire and commit a dramatic act of nonviolent civil disobedience — Jesus didn’t hit anybody or hurt anybody — you’re going to be arrested, tortured, and executed. That’s what happened to Jesus, according to the Gospels. He was confrontational, daring, even revolutionary.

The challenge to Christians is to continue the story. That’s what the Resurrection is about, I think: we carry on the story. But it’s hard, and we don’t want to do it, so we’ve come up with all these different theologies. The technical term for what you’re describing is “high Christology” — the belief that Jesus is God, and therefore we don’t have to do what he did. But Jesus is also fully human, and he wants us to follow him. Even if every other Christian in the world supports war, I’m going to say that Jesus calls us to peace.

I’ve been leading retreats around the country on the Sermon on the Mount. Gandhi read from the Sermon on the Mount every day for forty-five years. He said it was the greatest teaching on nonviolence in the history of the world. And it ends, in Matthew 7, with Jesus saying that Christians who say to him, “Lord, Lord,” but do not do what God wants, will not enter the kingdom of heaven. He wants us to love our enemies and bring justice for the poor. He wants us to forgive everyone and not judge anyone and create a new world without war and poverty. That’s the spiritual life.

Malkin: Gandhi, among other things, was a strict vegetarian. There was a time when one of his children was ill, and doctors recommended a meat broth, and Gandhi said, “The life of a lamb is no less precious than that of a human being.” You have written a booklet for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals called “Christianity and Vegetarianism.” What is it about Jesus’s life and actions that you feel supports vegetarianism?

Dear: I think that everything is connected — every aspect of how you live and what you do: it’s all one. We’re supposed to be at peace with all of creation and to side with the poor of the earth.

I became a vegetarian because I want to end starvation. The UN says that 900 million people are hungry and twenty-five thousand people die of starvation every day. In 1982 I read Frances Moore Lappé’s Diet for a Small Planet, in which she argues that if Americans became vegetarians, we could help end world hunger. She says not to eat McDonald’s hamburgers, not just because they’re unhealthy or because you don’t want to kill cows, but because you want to stop starvation. I was with Thich Nhat Hanh, the great Buddhist teacher, last year on retreat, and he said he didn’t think that anyone can care for the earth and eat meat, because raising cattle is speeding the destruction of the environment.

Maybe Jesus didn’t say not to eat meat, but he did say to feed the hungry. We could argue about the Passover lamb, but what would Jesus be doing today if he saw what eating meat is doing to the earth and how it affects the poor? Clearly he would be a vegetarian.

Malkin: Are there particular parts of Jesus’s life or actions that illustrate for you his commitment to nonviolence and opposition to empire?

Dear: The Gospels portray him as a radical nonviolent resister in everything he does. For example, his struggle in the desert with temptations: these are the basic human temptations that lead to violence — the desire to have power and to use that power. When the devil demands that Jesus demonstrate his supernatural powers, it’s like when someone demands, “You say you’re really against war? Then do something to stop it!” These are all temptations that lead to violence, and Jesus remains nonviolent to the end.

When the sick touch Jesus, they feel better. In my reading of that, they feel better because he’s perfectly nonviolent. There’s not a trace of violence in him. That’s what healing is about: being freed of violence. The rest of us have the Pentagon inside us; we’re addicted to violence. The spiritual journey is to let God disarm us and move us toward inner nonviolence.

Jesus also teaches nonviolence directly. No one in recorded history had ever before said, “Love your enemies.” I think it’s the most astonishing, revolutionary teaching ever. He says we should love our enemies because God loves God’s enemies.

The Eucharist, too, goes completely against the culture of violence. Jesus gives his followers bread and wine as a way to remember him and says, “This is my body, broken for you. This is my blood, shed for you.” He could have said, “Give me your bodies, broken for me,” or, “Go and shed their blood for me.” That’s what most rulers would say. But Jesus says, “I’m laying down my life for you.” It’s just perfect, unconditional, nonviolent love.

As he dies on the cross, he forgives the people who execute him. We all nurse resentments and grudges, but Jesus forgives even his murderers. At the core of nonviolence is the willingness to forgive.

Malkin: Among nonviolent activists, is there ever a tendency to compete in terms of the risks one is willing to take, the number of times one is arrested? Is there a temptation to wear one’s time in jail as a badge of honor?

Dear: We live in a culture that’s all about getting ahead, beating the other guy, and becoming number one, so it’s only natural that people in movements are competitive. The challenge is to try to model the peace we seek. If we want a world of nonviolence, we have to become people of nonviolence.

But I don’t think activists trying to outdo one another in going to jail is a big problem for us today. If it were, we would have thousands imprisoned for protesting the U.S. war machine. In India, at the height of Gandhi’s protest, there were more than three hundred thousand people in jail, and stories are told of children arguing, saying that parents who received only two years in prison were not serious freedom fighters. This is not yet our problem!

Still, the question of ego is a struggle for me, as it is for everyone. Nonviolence is certainly a journey toward humility, egolessness, and selflessness. Getting arrested and going to jail is actually a good way to deflate one’s ego, because the experience is always humiliating. I have been yelled at and mocked by police and guards. The trick is to move from pride to personal dignity.

Malkin: You’ve called modern peace activists the “new abolitionists.” What did you mean by that?

Dear: I marvel at the abolitionists of old, who campaigned for the abolition of slavery. Everyone told them they were crazy. Often their homes were burned and their lives threatened. But they held up their vision of a new world of equality, presenting it for all to see. Sometimes they gave their lives pursuing it.

We have to do the same thing today. When we campaign for an end to war, poverty, nuclear weapons, or global warming, we are the new abolitionists. We lift up the vision of a new world of peace that few people can see or even imagine. Everywhere I go, people tell me I’m unrealistic, too idealistic or naive or utopian; that I don’t live in the real world. I say: This is our future! A new world of nonviolence is coming! The world of violence is killing us all. If we are to survive, we all have to become people of active nonviolence.

Nonviolence is certainly a journey toward humility, egolessness, and selflessness. Getting arrested and going to jail is actually a good way to deflate one’s ego, because the experience is always humiliating.

Malkin: How do you avoid burnout and stay centered? Do you have a daily practice of some sort?

Dear: Every spiritual tradition demands a daily discipline. For me that means taking a certain amount of time to sit and welcome God’s love and allow God to disarm me and heal me of my violence, anger, and hostilities. The more I do this, the more I remember that I am loved by God, just as every human being is loved. It makes it easier for me to continue this hard work for justice and peace, because I know that it is God’s work, that the outcome is in God’s hands. Whenever I feel like I’m in charge, like this is my work, I quickly fall into despair and need to start over again. When I engage in civil disobedience, I often find myself renewed and strengthened. As Daniel Berrigan once said, “The best way to be hopeful is to do hopeful things.”

Malkin: Have you ever come close to breaking your vow of nonviolence and striking back physically?

Dear: No. I have been physically threatened and struck a few times — in El Salvador, in jail, and at a drop-in center for the homeless where I worked in Washington, D.C. The vow that kept me from retaliating also saved me, because in all of those situations, had I responded with physical violence, I believe I would have been beaten up or perhaps killed. The death squads in El Salvador and the prison guards who threatened and provoked me all had weapons.

The more frequent challenge for me is to respond without anger to Church people and others who mock me, ostracize me, or condemn me for my work for peace and justice. I’m continually trying to forgive, let go of resentment, and cultivate a nonviolence of the heart. It’s also hard to forgive myself.

Malkin: Is it possible to reconcile Christianity as you practice it with the power of the state, or will Christians who follow Jesus’s example always be at odds with the government?

Dear: I’m not sure it is possible to have a nonviolent state. Every government kills people. I sometimes think that is the purpose of government: to kill to protect national interests. But we can certainly do better. The government of Costa Rica, which has no army, is much more Christian than the government of the United States.

We are all, first and foremost, citizens of God’s kingdom of peace, love, and nonviolence. The Sermon on the Mount is our blueprint, our strategy, our plan for the future. We need to start doing what the early Christians did and refuse to fight or kill or join the army or support the empire. Every Christian who is in the U.S. military or who works making weapons should quit. Alas, most Christians support war and killing. We have a long way to go if we are to return to the Gospel of Jesus.

Malkin: How do you reconcile the loving God of the New Testament with the angry God of the Old?

Dear: The Church teaches that there is a slow revelation of God throughout the Scriptures. The early Hebrew Scriptures come to the conclusion that God is one but is violent and warlike. Then, in the Prophets, we learn that God sides with the poor and the oppressed and wants peace. Finally, in the Gospels, we read of the nonviolent Jesus, who says he fulfills the law and the prophets. He commands us to love our enemies, so that we will truly be sons and daughters of the God who “makes the sun rise on the bad and the good” and “the rain fall on the unjust and the just.” We see that God loves everyone, and as children of God, we are called to love everyone too.

We are still on this journey toward understanding the nature of God, and also our own nature, what it means to be human. But the Gospels clearly portray a nonviolent God. That’s the scandal of Christianity.

Malkin: What would you say to the criticism that protests like yours don’t change hearts and minds but just stir up controversy and conflict?

Dear: Today we maintain thousands of nuclear weapons as if that were perfectly normal. Nine hundred million people are starving to death. We’re teetering on the brink of catastrophic global climate change. Dozens of wars are raging. We cannot sit back and allow these evils to destroy us. I think stirring up controversy and conflict is a good first step.

Martin Luther King Jr. said that, in such times, hostile public reaction is to be expected. People have grown comfortable with war and injustice. When we advocate changing our lives, our country, and our world far beyond the election of a new president, people will resist that change.

So we have to expect opposition to our work for peace and justice. That’s another opportunity to practice nonviolence, love others, and still insist on the truth of peace. We can do this because we know that God is at work among us, disarming us all.