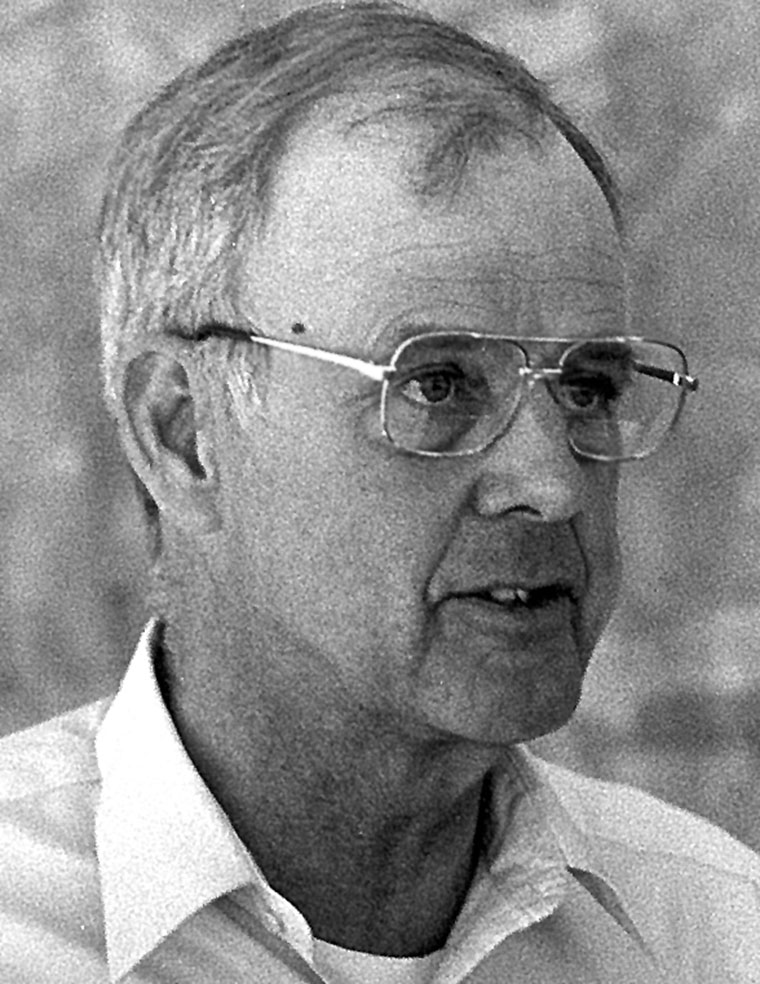

For more than forty years, Wendell Berry has worked his family farm in Kentucky the old-fashioned way, using horses as much as possible and producing much of his own food. And he has published more than forty books, writing by hand in the daylight to reduce his reliance on electricity derived from strip-mined coal. Berry has been called a “prophet” by the New York Times, and his Jeffersonian values are so old they can appear startlingly new. His strong pro-environment position has made him something of a cult hero on the Left, as have his antiwar sentiments, which have grown sharper over the years. His 1987 essay “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer,” published in Harper’s, led some to accuse him of being antitechnology, a Luddite. For his part, Berry has criticized environmentalists for not working to protect farms as well as wilderness. His stout self-reliance and unabashed use of moral and religious language in his writing have endeared him to a number of conservatives, even as his stance against corporate globalization has drawn criticism from others. But these apparent contradictions don’t seem to bother Berry one whit.

Born in 1934 in Henry County, Kentucky, Berry published his first book, the novel Nathan Coulter (North Point Press), in 1960. A steady stream of publications in various genres followed, along with honors from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation. Poet Wallace Stegner once noted, “It is hard to say whether I like [Berry] better as a poet, an essayist, or a novelist. He is all three, at a high level.” Some of Berry’s better-known titles include A Place on Earth (Counterpoint), which the New York Times Book Review called “a masterpiece”; Collected Poems 1957–1982 (North Point Press); Another Turn of the Crank (Counterpoint); and The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (Sierra Club Books). The rural Kentucky of his fiction has often been compared to William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Like Faulkner, Berry has an ear for local language and a feel for place.

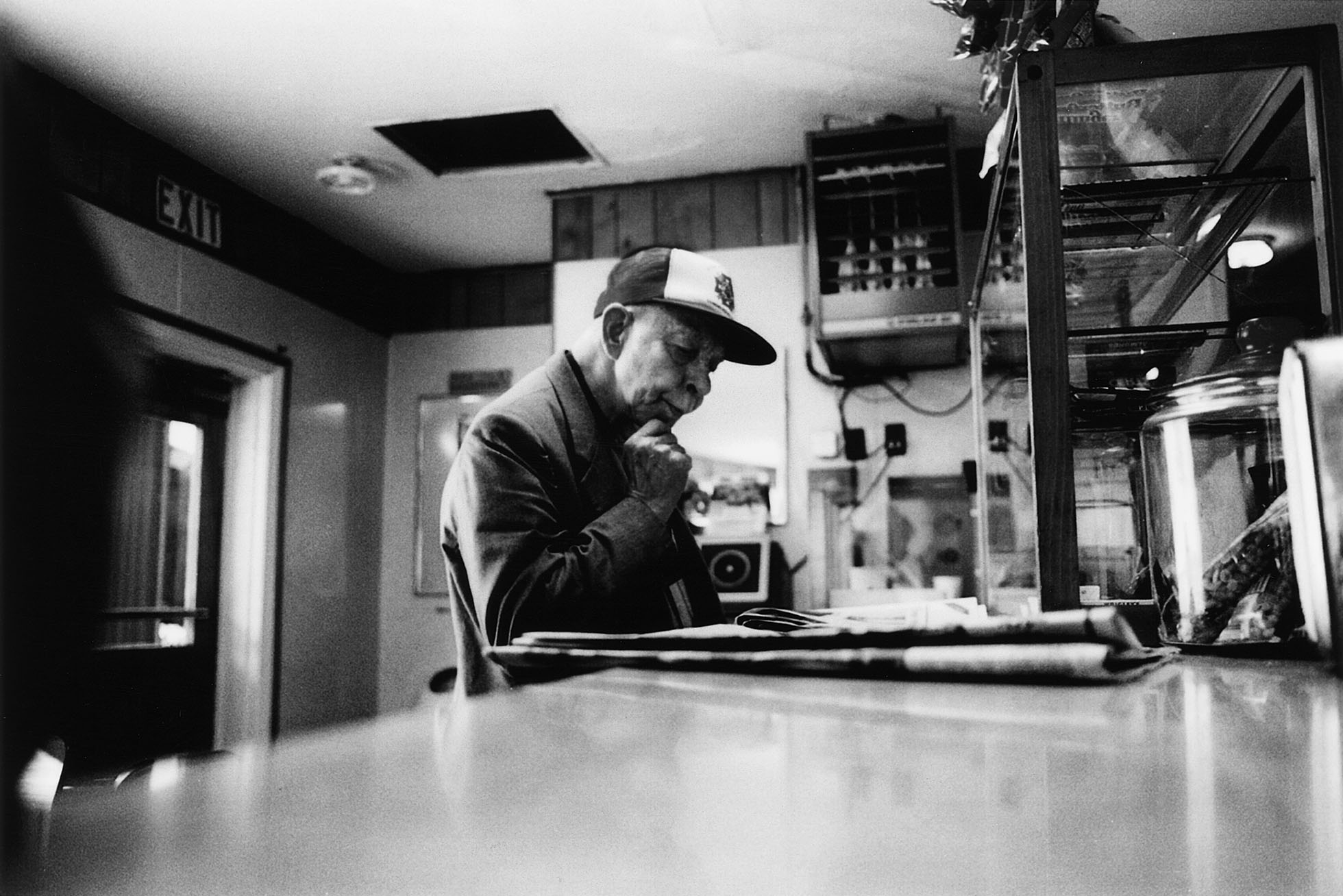

Berry taught for more than two decades at Stanford University, New York University, and the University of Kentucky, but he has now quit teaching. Since 1965 he has lived and worked on the 125-acre Lanes Landing Farm in the county of his birth. It was there that my wife and I visited him one Sunday afternoon. He was exactly what I would expect a gentleman farmer to be: tall, rangy in both body and mind, sagacious, and gracious. He and Tanya, his wife of fifty years, were impeccable hosts, making sure that we were seated comfortably on the porch and that our glasses of lemonade remained full. Earlier in the week, I had heard Berry speak to the Sierra Club in Louisville. Despite his busy schedule, he answered my questions in a thoughtful and deliberate manner reminiscent of his prose. The conversation touched on all the primary themes in his tremendous body of work: the importance of place, sustainability, and — above all — community.

WENDELL BERRY

Fearnside: Stopping by a local eatery on the way here, I asked people what they might want to ask you. Henry County is small, they noted, and farming isn’t very profitable anymore. So, why did you stay when you could have left for, as one waitress put it, “glitz and glamour” elsewhere?

Berry: I just happen to have no appetite for glitz and glamour. I like it here. This place has furnished its quota of people who’ve helped each other, cared for each other, and tried to be fair. I have known some of them, living and dead, whom I’ve loved deeply, and being here reminds me of them. This has given my days a quality that they wouldn’t have had if I’d moved away.

There have been some good farmers here. The way of farming that I grew up with was conservative in the best sense. I learned a lot from people in Henry County. Probably all my most influential teachers lived here, when you get right down to it. I owe big debts to teachers in universities, to literary influences, and so on. But it’s the people you listened to as a child whose influence is immeasurable — especially your grandparents, your parents, your older friends. I’ve paid a lot of attention to older people. Of course, not a lot of people here are older than I am anymore, but some are, and I still love to listen to them, to my immense improvement and pleasure.

Fearnside: What are some of the things that they say?

Berry: They tell stories. They talk about relationships. They talk about events that have stuck in their minds. The most important thing is not what they say, but the way they talk. We had a local pattern of speech at one time. Now we’re running out of people who speak it. But there were once people here whose speech was uninfluenced by the media, and it had an immediacy, a loveliness when it was intelligently used, and a great capacity for humor.

Fearnside: A good friend of mine told me that she knows people from Kentucky who have trained themselves not to speak like Kentuckians.

Berry: That was the main goal of the school system: to stop you from talking like a “hick” and get you to speak standard American.

Fearnside: When you speak of what the elders here in Henry County discuss, it reminds me of a line from Barry Lopez’s short-story collection Winter Count: “That is all that is holding us together, stories and compassion.”

Berry: I don’t think we’re just stories — we’re living souls, too — but we’d be nothing without stories. Of course, stories that belong to a landscape are different from stories that don’t. In Arctic Dreams Lopez talks about how the Eskimos, the native Alaskan people, have a cultural landscape — the landscape as they know it — that is always a little different from the actual landscape, which nobody ever will fully know.

In a functioning culture the landscape is full of stories. Stories adhere to it. And they’re most interesting when they’re told within the landscape. If, say, an oral-history project records somebody’s story and puts it in the university archives, then it’s a different story. It’s become isolated, misplaced, displaced.

Fearnside: You’re a well-known advocate for local economies, yet you write for a much-wider-than-local audience, which means you must rely on the machinery of the corporate world to get your message out. Is there a contradiction in this, or is it simply an inescapable paradox that you must be pragmatic about?

Berry: There are contradictions in it, no doubt about that. There’s an absolutely lethal contradiction in my driving and flying around to talk about conservation and local economies. But you have to live in the world the way it is. You can’t declare yourself too good for it and move away. You have to carry the effort wherever you can take it. You’ve got to have allies. The thought of the Committees of Correspondence in the American Revolution is never very far from my mind. People have to stay in touch somehow. They have to meet and talk. They have to support each other. But that’s a network, not a community.

Fearnside: I was fortunate once to participate in a barn raising in Idaho. It was an incredible experience of community. With the help of friends and neighbors, using mostly hand-held tools, a couple raised a barn in a day and a half.

Berry: The Amish do it in a day. They belong to a traditional culture that, for a long time, has steadfastly put the community first.

Fearnside: I’ve noticed that the Amish seem less self-conscious than most Americans. Why do you think this is so?

Berry: I’d say that in their community, honesty is the norm. One of the most striking things about the Amish is that their countenances are open. We pity Muslim women for wearing veils, yet almost every face in this country is veiled by suspicion and fear. You can’t walk down a city street and get anybody to look at you. People’s countenances are undercover operations here.

Fearnside: While traveling in the Xinjiang Province of China — which is predominantly Uyghur, a traditional Muslim culture — I was struck by the people’s openness. In particular, the children radiated gaiety and health, just as Amish children do.

Berry: The Amish children are raised at home by two parents. They’re given little jobs to do from the time they’re able to walk, and they’re important to the family economy. They have rules. They’re secure. There are things that they’re not allowed to do. There’s something pitiful about American children who are left to invent a childhood on their own with one parent or none, no community, no relatives, and nothing useful to do. They don’t even go into the woods and hunt.

Fearnside: I fear that my generation may be the last to grow up outdoors. I used to roam for hours, hiking through the fields and woods or bicycling down country roads, completely unsupervised, which is unheard of today. Nowadays a kid is going to grow up sitting in front of a computer screen or listening to an iPod, not climbing trees or even playing ball in the street.

Berry: Young people around here don’t come to the river to swim or fish anymore. Of course, an alarming percentage of Kentucky streams aren’t fit for swimming or fishing.

Fearnside: It seems that we’ve been separated from our local communities by radio, television, and now the Internet. Because these forces come from outside the communities, they often don’t reflect the communities’ values. How can we stay plugged in to information and yet preserve our local connections?

Berry: I don’t know. There’s not much you can do, unless you want to disconnect yourself from those electronic gadgets. I pretty much do. Tanya and I haven’t had a television for a long time; people used to give tv sets to our children, because they felt sorry for us. I think we were given three over the years. I listen to the radio some. I don’t have a computer, and I almost never see a movie. To me this isolation is necessary. It keeps my language available to me in a way that I don’t think it would be if I were full of that public information all the time.

Fearnside: My wife and I enjoy watching movies on dvd, but we find that most mass-media offerings aren’t worth our time.

Berry: To make yourself a passive receptacle for information, or whatever anybody wants to pour into you, is a bad idea. To be informed used to be a meaningful experience; it meant “to be formed from within.” But information now is just a bunch of disconnected data or entertainment and, as such, may be worthless, perhaps harmful. As T.S. Eliot wrote a long time ago, information is different from knowledge, and it has nothing at all to do with wisdom.

Fearnside: In your recent talk to the Sierra Club, you mentioned “foodsheds.” Can you explain this concept in more detail?

Berry: Cities attract food products from the countryside the same way that a major stream attracts water from the smaller streams in a watershed. A foodshed would be the tributary landscape around a city from which the city’s food would come. It goes back to the ancient concept of the city as a gathering point for the products of its landscape. And since we haven’t had cheap petroleum for a while — and we’re probably not going to have it ever again — we need to think this way once more. Sooner or later, we’re not going to be able to afford to haul food in from everywhere in the world.

Another reason to think in terms of local food economies is that an extended food system concentrates food at collecting points and transportation arteries, so it’s extremely vulnerable to blockades or acts of terrorism. A third reason — and this may be the most important reason of all — is that if you’re going to have sustainable agriculture, it has to be adapted locally. Local adaptation means that you observe in the economic landscape the same processes that you find in healthy natural landscapes: You must have diversity. You must have both plants and animals. You must waste nothing. You must obey the law of return — that is, you must return to the ground all the nutrients that you take from it. You must protect the soil from erosion at all times. You must make maximum use of sunlight. In those circumstances, you may leave the crops and animals pretty much to fend for themselves against diseases. The farm will have some disease, but it won’t have epidemics. If you look at a healthy forest, for instance, you see some prematurely dead trees, but not massive numbers of them.

Fearnside: This sounds like the opposite of the monocrop agribusiness model that we have today.

Berry: That’s right. It’s the diametric opposite of reductive science, and industrial agriculture is based on reductive science.

Fearnside: If what you’re talking about is natural, how did we stray from it in the first place?

Berry: It’s not natural; it’s a conscious, deliberate imitation of natural processes. The farm imitates the diversity of the forest.

Fearnside: So you’re talking about farming more as an art than a science.

Berry: It’s both. Art is a way of making, and science is a way of knowing. You’re never going to escape the need for either one; you’ve got to have a certain amount of knowledge, and you’ve got to have a certain amount of art. You’ve got to know how to make a thing — whether it’s a crop or a novel — and you’ve got to have a way of making it.

Fearnside: You mentioned threats to our food security. How can communities ensure their food security?

Berry: They have to maintain the health of their local landscapes, and they have to provide a livable income to the people who work those landscapes. That’s it.

We pity Muslim women for wearing veils, yet almost every face in this country is veiled by suspicion and fear. You can’t walk down a city street and get anybody to look at you. People’s countenances are undercover operations here.

Fearnside: In your Sierra Club talk, you said that you would like conservationists to become more interested in “economic landscapes” — in working farms, ranches, and forests. Do you feel that most people’s definition of the natural world is too small?

Berry: The human definition of the natural world is always going to be too small, because the world’s more diverse and complex than we can ever know. We’re not going to comprehend it; it comprehends us. The question is whether we can use it with respect. Some people in the past who knew very little biology were able to use the land without destroying it. We, who know a great deal of biology, are destroying our land in order to use it.

Fearnside: Your emphasis is on local economies, not on organic farming. Why?

Berry: “Organic” has become a label, as it was destined to be. It’s a completely worthless word now. It has been perverted to suit the needs of industrial agriculture.

Fearnside: Many people buy organic because it’s healthy.

Berry: That’s true, but in a local food economy, consumers could exert a certain pressure on producers, and rather than push for convenience or even cheapness, informed consumers would apply pressure on behalf of health, sustainability, and security. So the natural tendency in a local food economy would be toward healthfulness.

Fearnside: Do you think that our unhealthy food practices have to do with our lack of connection to the sacred?

Berry: I would say so, because when you are in the presence of something you consider sacred, the natural response is to be humble and respectful and careful. This is dependent on the scale of the endeavor not being too large, and on a proper ratio between the amount of land needing care and the number of caretakers. Ecologist Wes Jackson calls that the “eyes-to-acres ratio,” and it varies according to the type of farm. A ranch in New Mexico with a good grazing program can get by with fewer people than a highly diversified Kentucky farm.

Fearnside: Should the responsibility for changing the food system lie more with the consumer, more with the producer, or equally with both?

Berry: When the producers — the farmers — are going broke, it’s wrong to expect them to reform the system. In fact, there are too few actual farmers left to reform anything. So, as a practical matter, reform is going to have to come from consumers. Industrial agriculture is an urban invention, and if agriculture is going to be reinvented, it’s going to have to be reinvented by urban people.

Fearnside: Those concerned about the land often try to quantify its worth — for example, calculating the monetary worth of a forest to demonstrate why it should remain uncut. Wouldn’t it be better to help people understand the unquantifiable value of a healthy environment?

Berry: Quantification is useful up to a point. You can’t quantify the true value of a forest that is going to be destroyed by mountaintop-removal mining, but to the extent that it can be quantified, I think it ought to be. Any good forester should be able to tell you what the value of that timber would be over, say, two hundred years of sustainable production, and we can compare that to the current dollar value of the coal under the mountain and make a financial argument for keeping the forest. That sort of comparison ought to be done, but it isn’t.

It’s possible to figure out what a city’s annual consumption of products from the land economy is: How much food do the people in the city eat? How much do they require in the way of forest products? How much do they require in the way of mined minerals or fuels? Those numbers can be produced, but we don’t have them, as far as I can tell. Economists and businessmen who are supposed to be hardheaded realists and materialists, concerned about scientific fact, never have these numbers. There’s such a thing as professional bullshit, and this is it.

Fearnside: Mountaintop removal has been called “strip mining on steroids.” Yet it hasn’t generated a lot of press, despite how widespread and damaging it is. Why do you think this is?

Berry: I can’t tell you. That Kentucky coal-slurry pond that broke loose in October 2000 spilled thirty times the pollution that the Exxon Valdez let go in Alaska. The Valdez completely took over public attention, but the Martin County spill didn’t even make the New York Times. Maybe one of the eastern-Kentucky people I’ve seen quoted had it right when he said, “We ain’t as cute as them otters” — which is a heartbreaking statement. This ruination is happening in what’s called a “national sacrifice area,” a term that has some truth to it: the Appalachian coal fields were given up to exploitation a hundred years ago.

Fearnside: The Valdez spill happened in 1989. Since then we’ve had so many new environmental disasters that the press and the public may be becoming numb to them.

Berry: If you’ve lost the capacity to be outraged by what’s outrageous, you’re dead. Somebody ought to come and haul you off.

Fearnside: It’s ironic that we treat time, of which we have an abundance, as a scarce commodity, whereas we treat finite commodities, such as topsoil and fossil fuels, as limitless.

Berry: Actually, though at present we are using topsoil as a finite quantity, as long as you keep it in place, take proper care of it, observe the law of return, and balance the forces of growth and decay, topsoil is an infinite resource. It has the capacity to go on and on. A man named F.H. King traveled in Asia in 1907 or so and wrote a book called Farmers of Forty Centuries. His question on that trip was: How is it that these people have kept their land in production for four thousand years? (Some now think it was longer.) It’s a practical, obvious question. Anybody of normal intelligence should think to ask it. But for the last fifty years or more, no certified agricultural expert has asked it.

The human definition of the natural world is always going to be too small, because the world’s more diverse and complex than we can ever know. We’re not going to comprehend it; it comprehends us. . . . Some people in the past who knew very little biology were able to use the land without destroying it. We, who know a great deal of biology, are destroying our land in order to use it.

Fearnside: I came to Kentucky after four years of living in Central Asia, and I was struck by how environmental disasters both here and there have the same causes: shortsightedness, greed, and the concentration of wealth among a powerful elite. Do you think these are simply part of human nature?

Berry: Greed is a part of human nature, and greed is the root cause of these disasters. Once you have greed and the means of exploitation, the high-toned rationalizations — in other words, the excuses — follow as a matter of course. A real culture functions to limit greed. Our culture functions to increase it, because, we are repeatedly told, it’s profitable to do so, though the majority of the profits go to only a few people.

Fearnside: We’ve talked about what consumers and producers can do to change things. What should the role of government be?

Berry: The appropriate role of government should be to see that power and money don’t accumulate in too few hands.

Fearnside: But too often governments act in their own self-interest and harm the people they’re supposed to be working for and protecting.

Berry: Unless a community consists entirely of like-minded individuals, the community must, to some extent, have laws, which means government. It’s the nature of an organization like a government — or a corporation — to be self-aggrandizing and self-perpetuating. Once it starts running, it aims to keep running. The real limit on government would be reasonably independent, self-sustaining localities and communities. But if there is no local independence, then governments and other organizations have a kind of freedom that they wouldn’t have otherwise.

If you’ve got 300 million people, most of whom produce nothing for themselves or for the community and to whom everything has to be brought from somewhere else, then there’s no way you’re going to have limited government, or limited anything. All organizations feed upon the helplessness and ignorance and passivity of the people.

Fearnside: At the same time, governments and corporations are made up of people.

Berry: People who go to work for corporations essentially abandon their integrity as individuals in order to serve the corporation. And the corporation has a set of rationalizations and excuses for its behavior that the people within it subscribe to, which means they have no moral force of their own. It’s impossible for them to think for themselves or have a contrary opinion.

Fearnside: For most of us, work no longer satisfies our real needs, and so we must convince ourselves that what we do is needed. On the grossest level, that’s all advertising or public relations is: creating a need for things that aren’t needed.

Berry: You’re right. The whole system depends on the ability of the people in power to convince the rest that they’ll be better off if they buy certain products or elect certain candidates. If a company has a better product, they don’t explain why it’s a better product. They make false promises, telling you you’ll be truly happy at last if you’ll buy whatever it is they’re selling. We used to call this “lying.”

Fearnside: In your own writing, you seem to confront head-on the speed and thoughtlessness of contemporary society by your deliberate, thoughtful style. Do you consciously write this way?

Berry: I did make up my mind at some time that instead of trying to serve my purposes by rhetorical artifice or personal attacks, I would try to make as much sense as I could. If your cause doesn’t make sense, why defend it? Writing is a test of sense. It’s an exposure of your ideas to your own scrutiny, and then to the scrutiny of other people.

Fearnside: The decline in reading in the U.S. has often been blamed on writers having become too disconnected from the people and their writing having become too abstruse.

Berry: Real reading, of course, is a kind of work. But it’s lovely work. To read well, you have to respond actively to what the writer’s saying. You can’t just lie there on the couch and let it pour over you. You may have to read with a pencil in hand and underline passages and write notes in the margins. The poet John Milton understood that the best readers are rare. He prayed to his muse that he might a “fit audience find, though few.”

Fearnside: In your preface to Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community [Pantheon], you wrote a beautiful refutation of the idea of intellectual property: “As I understand it, I am being paid only for my work in arranging the words; my property is that arrangement. The thoughts in this book, on the contrary, are not mine. They came freely to me, and I give them freely away.” Where do your ideas come from?

Berry: It’s awfully hard to have an idea that somebody else hasn’t already had, you know. The French writer André Gide worried that he wasn’t original enough, and then he finally consoled himself by realizing that the same things need to be said over and over again, because the times change, and the context shifts, and the language changes, and ideas need to be expressed again in new ways, to be submitted anew to the test of sentences.

But I don’t have much gift for abstract ideas. I’m usually moved to write by practical problems that I’m interested in. And when I lose sight of the problems, I lose interest.

Fearnside: You have certainly stuck to writing as stubbornly and passionately as you have to farming an old, worn-out Kentucky hillside. Is such stick-to-itiveness essential to success as a writer, or in any endeavor?

Berry: Practice is essential. If you’re going to learn to write, it has to be your practice. I’ve been fascinated with the job of learning to write, which is unending. And I enjoy writing. Dealing with the problems it presents gives me pleasure. Sometimes there’s frustration, but if I get frustrated or hit an impasse, I just stop and go back to it later. I don’t like to hear writers talk about how they suffer for their craft. If it’s that bad, they ought to quit.

Fearnside: You left your job as a professor at the University of Kentucky. Why did that position become untenable?

Berry: I had so much going on outside the university, so many obligations and causes, that I needed to quit something. And I’m not a very good employee. I don’t like bosses. I don’t like being under the expectations of a damned administration, and the universities are getting more administrative and industrialized: too much rigmarole, not enough substance.

Fearnside: Is the influence of global businesses, which increasingly are endowing scholarships, professorships, and chairs, threatening the objectivity of research being conducted at universities?

Berry: There’s real concern for the context of the work being done in the universities today. The assumption that professors can concern themselves only with their specialties, and that the results will somehow be used for good, is bankrupt, shot. Too many bad results have come of well-intentioned work. The old intellectual structure is breaking down. Academic life is going to have to rearrange itself so that it can deal with consequences and responsibilities. The shallow optimism of the specialist system is no longer tenable.

On the other hand, we need specialists, to some extent. If you want the best masonry, for example, you’ve got to have people who know the trade secrets. Your amateur householder who decides to build a stone wall is almost certainly not going to build the best possible stone wall, and any civilization worth anything at all wants the best possible stone walls. So you’ve got to have people who are practiced. But there’s a limit. If this person becomes so specialized that he or she can’t speak to ordinary people or to other kinds of specialists, then something’s wrong.

Fearnside: How can writers, especially those who don’t find success through corporate publishing, support themselves and still have enough time to produce a body of work?

Berry: I don’t think there’s an answer to that question except the ones writers make for themselves. I’ve written pretty steadily over the years and farmed pretty steadily, and I’ve always had to have a third source of income. Sometimes it was teaching. And for ten years I earned the extra income we needed by lecturing and giving readings. I could get a thousand dollars sometimes to speak at a college. But to do that, I had to make phone calls and reservations, and write the speeches, and take the trips, and then come home and do the things I ought to have been doing while I was gone. It’s not easy. If you have children, it’s more of a struggle — not that that should stop anyone from having children if they want them.

We had two friends, Harlan and Anna Hubbard, who had a little income from renting out Harlan’s mother’s house after she died. I think that was all the regular income they had. Harlan painted and wrote, and he and Anna played music every day. They lived, as Harlan put it, “on the fringe of society.” They didn’t have electricity. All their technology was nineteenth century. But they were satisfied, and they lived a great life — they made a great life. It was a work of art.

Fearnside: So their answer was to simplify their lives so that they required less income and could do the things they were passionate about.

Berry: They reduced costs, but when you do that, you make your life more complex. It’s much simpler to live by shopping.

Fearnside: For me, as for many people, being a writer means getting up early in the morning — sometimes when it’s dark — writing as much as possible, and then going out and working a full-time job. I’m content with this, knowing that I’m doing my best under the circumstances, and I define myself as a writer even though I’m not writing full time or earning my living from it.

Berry: That’s good, but you need to realize something else: that you can lead a perfectly good and satisfactory life even if you’re not a writer. When I figured out that I could be perfectly happy and not be a writer, I became a better writer.

Fearnside: But you never gave up writing.

Berry: No, but I don’t think you ought to let your happiness depend on writing. There are a lot of worthwhile things you can do. The unhappiest people in the world may be the ones who think their happiness depends on artistic success of some kind.

Fearnside: In the 1960s you wrote the poem “The Morning’s News” in reaction to the Vietnam War: “I will purge my mind of the airy claims / of church and state, and observe the ancient wisdom / of tribesman and peasant, who understood / they labored on the earth only to lie down in it / in peace, and were content. I will serve the earth.” All these years later, with our country in the midst of another terrible war, do those lines still describe how you feel?

Berry: I suppose so. I’m doubtful I would put it that way now, but I’m not going to subscribe to anybody’s excuse for coldblooded killing. There’s no such thing as a “just” war anymore, if there ever was. You can’t defend bombing children and innocent people. It isn’t right to teach people how to torture and kill each other. Wars never end, really. The Crusades aren’t quite over yet. Our Civil War certainly isn’t over yet. I don’t think we can afford this kind of behavior anymore. Nobody’s talking about the ecological damage of war.

If you’ve lost the capacity to be outraged by what’s outrageous, you’re dead. Somebody ought to come and haul you off.

Fearnside: When the army practices bombing at Fort Knox, it rattles our windows a dozen or more miles away.

Berry: The guns and bombs from Indiana’s Jefferson Proving Ground, which is now decommissioned, rattled windows here for two generations.

Fearnside: My wife and I feel depressed when we think about how many millions of dollars are being blown up in our backyard.

Berry: It’s great for wildlife protection, though, because nobody can go where they’ve got all that unexploded ordnance. The Jefferson Proving Ground is now a wildlife refuge. They’ve got unexploded ordnance and depleted uranium, and they’ve got rare birds, too. It sounds like a joke, but it’s a fact.

Fearnside: In your book Blessed Are the Peacemakers: Christ’s Teachings about Love, Compassion, and Forgiveness [Shoemaker & Hoard], you write that until recently the scale of wars was relatively small and the destruction relatively controlled. Yet Genghis Khan massacred millions of innocent civilians, and the Bible speaks of pillaging on a scale that’s appalling even today. Why this belief that, once upon a time, war was more civilized?

Berry: I don’t mean it was more civilized. I just mean that the weapons weren’t as destructive. I don’t think wars ever were civilized, though the U.S. once conducted wars without torturing prisoners.

Fearnside: And the destructive power of war only grows. How can we justify blowing up buildings and infrastructure only to rebuild it all again at several times the original cost?

Berry: It’s good for business. If you were Halliburton, you’d look upon that as a business opportunity.

Fearnside: Do you really think people see it in such crude terms?

Berry: I think there are people who are perfectly capable of seeing it in those terms. If you can arrange somehow to be paid for building back what you’ve torn down, that’s an opportunity to make money. It’s also profitable to make weapons in the first place, and you’ve got to create a demand for more. We’ve got twelve thousand nuclear warheads. How does that make sense except in terms of some kind of insanity? Suicidal insanity. Plumb craziness. Or big business.

Fearnside: I used to be a newspaper journalist, and I had a chance to interview a number of World War ii veterans. None of them glorified war, seeing it as a last resort to be used only when all diplomacy has failed. Yet even as we hold these people up as heroes, we don’t heed their words.

Berry: Veterans are appropriated by the pro-war crowd. Not just veterans, but casualties, too. The appropriation of the dead is one of the worst war crimes. If you’re a soldier, as soon as you’re dead, the government says that you died for your country and that your sacrifice justifies the war.

Fearnside: The writer and Trappist monk Thomas Merton lived and wrote just a couple of hours up the road from here, at Gethsemani Abbey. Are you familiar with him?

Berry: I’ve read a number of his books. He interests me. He was a man capable of real seriousness, but he was capable of real merriment, too, and that’s important.

Fearnside: What interests me about Merton is that he believed that service and contemplation — which I interpret as right action and a constant scrutiny of the motives that inspire the action — could bring one closer to God. Do you believe this?

Berry: That’s fairly formulaic. I suppose the appropriate answer to something that formulaic is “Probably” or “Maybe.” Some of those formulas are all right; there’s no question about it. The monastic life is a formula.

The most important thing I’ve read by Merton is a series of talks he gave in Alaska, just before he left for Asia. Some people think that when he showed interest in the East he was abandoning his Christian commitment, but I think it’s clear in those talks that he wasn’t doing any such thing. He was talking earnestly to those people in Alaska about how we could get along with each other.

Fearnside: You’re a Christian.

Berry: I’m a subscriber to the Gospels; you could put it that way.

Fearnside: You strike me as being both devout and skeptical; firm in your faith, yet willing to question it. Do you see skepticism as something that nurtures your faith?

Berry: Faith implies skepticism. It implies doubt. Faith is not knowledge. It’s not the result of an empirical study. So I would think that people of faith would always be involved in some kind of maintenance to shore it up. Sometimes it’s easy to have faith, and sometimes it isn’t. Maybe if you’re in a monastery it’s easier, because everything there is established for the purpose of preserving your faith. The world, as it operates today, isn’t made to preserve it.

Fearnside: In your essay “Standing by Words” you note that love is not abstract and cannot lead to abstract action. Love is the catalyst for concrete action, which is taking responsibility for what we do here and now. It seems to me that in some ways this kind of love is the salvation of the world.

Berry: That’s true. But like religion, love has to be practiced. It has to find something to do. Love isn’t just a feeling. It’s an instruction: Love one another. That’s hard to do. It doesn’t mean to sit at home and have fond feelings. You’ve got to treat people as if you love them, whether you do or not.

Fearnside: The Buddhists try to follow a path of “right livelihood,” which means that a person should not engage in work that brings harm to others, either directly or indirectly.

Berry: Right livelihood would prohibit strip mining and building warplanes. And so would “Love one another,” if anybody took it seriously.