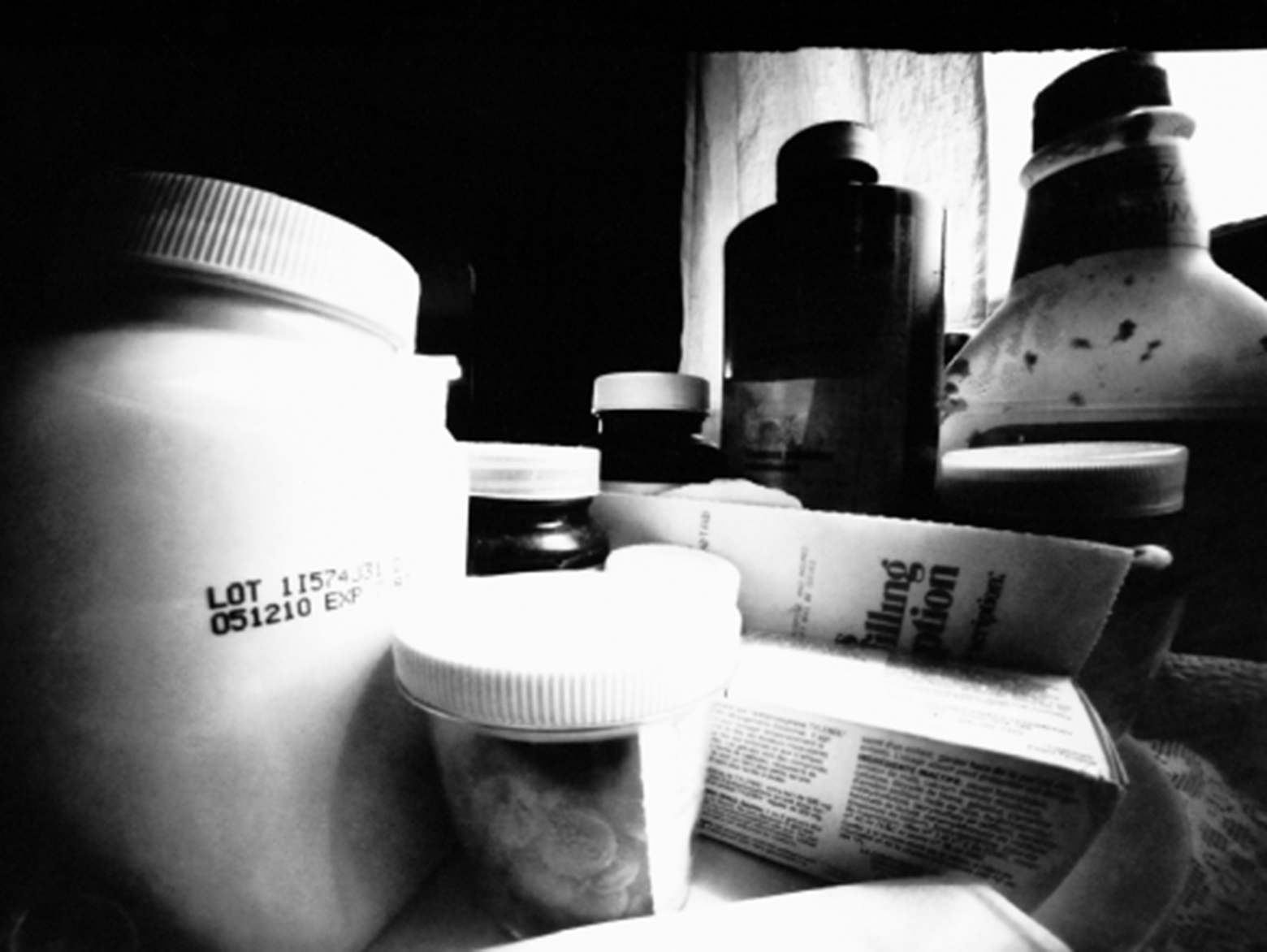

I felt good in the morning, almost strangely well. My daughter, my husband, and I sat together for a few minutes before he left for work and she left for school. (I was off that day.) I talked about my own job, as a nurse: how a patient on the psychiatric ward had constructed a complicated delusion in which a boil on his ass and the attack on the Pentagon were somehow connected. He had taped tiny American flags all over his hospital-issue pajamas. As I told them this, I felt almost elated. Was it because I had recently doubled my Prozac? Could the evening primrose I was taking really have restorative properties? Or was it the tyrosine, or the tryptophan, or the melatonin, or the DHEA? Who knew?

Perhaps it was the key I had in my pocket. It belonged to a swanky house in a swanky part of the next town. Through a strange series of events, I had been asked to care for the owners’ dog while they were away. This meant that, besides walking the dog, I could examine the contents of the nice elderly couple’s medicine cabinet down to the last Bactrim. I could look in the cabinet next to the sink in the kitchen and in the bedside drawer — anywhere anyone ever thought of keeping their pills. If either husband or wife had ever been prescribed Percocet (or, even better, Dilaudid), they probably had not discovered that opiates were the most wonderful substance ever invented. Rather, they had used the pills for pain, as prescribed, and left twenty-eight in the medicine cabinet. And I, in all my immoral glory, would pocket them and feel grrrrreat for three days. Afterward I’d feel awful, worse than awful, like something at the bottom of a cockatoo’s cage.

After my daughter and my husband had left, I jumped in my car and prayed the starter would work. It was scheduled to be replaced that day, while I was at my noon Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. In the meantime, getting the car to start was a dicey proposition. The engine turned over after four tries.

At the elderly couple’s house, I was surprised to see a car in the driveway and lights in the window. I knocked. The wife appeared.

I can’t say enough about how nice this woman is. She is just as pleasant as pleasant can be. Before my eyebrows could finish lifting, she said, “Oh, it’s next Monday, not this one.”

I’d like to think my face betrayed nothing, but my heart could be found in my left big toe. I would have no Percocet today. Instead, I would have a long conversation with this woman about ankylosing spondylitis and prednisone, teenagers and Venice. I would become reacquainted with the dog’s needs. Minutely. This done, I sat in my car and tried the starter six times before succeeding. I sailed away thinking, It’s OK. I felt oddly calm, not desperate at all. Maybe the AA was taking.

But I soon found myself at the nearest convenience store, perusing the wine selection. All I really wanted was a bottle with a screw top, as I didn’t have a corkscrew. Dressed the way I was, however — clearly a woman of intellect and taste — I had to make my selection appear to be based on something other than an immediate need for alcohol.

I finally settled on something sweet, cheap, and fruity. Back in the car, I gulped a quarter of the bottle, tried the starter seven times, and roared off toward home.

Ahhh, I thought. This is better. Now I could clean the house feeling sort of OK.

But I had to be careful: I couldn’t get too drunk before the AA meeting. I couldn’t smell like wine. If you want to spot an alcoholic, look for someone who is always chewing breath mints. This is worth ten points. Strong perfume counts for another ten. You get twenty for slightly over-the-top jocularity; twenty-five for an inadvertent slur. By the time I got to the church to set up for the meeting, I was in the fifty-point range.

On the way, I had to pick up Mary P., an older woman with no car. Mary irked me, because she had never drunk more than a couple of glasses of wine a day in her whole drinking career. No doubt my sponsor had instructed me to chauffeur Mary around thinking it would cure my resentment of her. And I had agreed because it would give me a chance to check Mary’s medicine cabinet. But when I got there, the cupboard was bare, and I was still stuck ferrying Mary. That was fine, though. I could hack it. Besides, I was building up a wicked karmic debt with all my cabinet investigations, and this might even the score a little.

I dropped Mary at the church, and while she made the coffee, I drove my car to the garage a mile away. The mechanic was a truly nice man.

Let’s face it: I’m surrounded by nice people. I live in a pretty, clean, safe place. I experienced some traumas as a child, but my mother was not raped in front of me; my house did not burn down and kill my family; I wasn’t born in Bosnia or sent to Siberia. I don’t have a good excuse.

Unless, of course, AA is right, and I have a disease — a progressive one that, unless I manage to remain abstinent, will doom me to jail, institutions, or death. So far I have experienced only the institutions. From what I’ve seen of my brother’s stint in jail, I’m not keen to explore that part of the prognosis. Death, on the other hand, is beginning to look like a reasonable option.

I left my car with my mechanic and walked back to the AA meeting.

At this point, I must mention that I had stolen some Lomotil, a diarrhea medication, at one of my jobs, hoping for whatever pathetic buzz it might grant me. It had made me constipated. Then I’d taken laxatives, to get my system going, but had gone too far in that direction and given myself the runs. While walking to the AA meeting, I farted, or thought I farted, and discovered that I had shit myself. I had to make a detour to the supermarket.

Fortunately, I had brought a small container of wine for emergencies, and I polished this off in the bathroom after cleaning myself up. Then I walked — with a rather wide gait — to the AA meeting. The coffee was ready, and I drank a cup, feeling nervous, my sinews straining with apparent goodwill.

Since I had set up the meeting, I got to pick the speaker. I chose a woman who had gotten sober at sixteen and had since made it to thirty-five without a slip. Her talk made me feel like something underneath the stuff at the bottom of a cockatoo’s cage.

Then several people spoke about how their Higher Power — or H.P., as we call it — was doing everything right: curing their cancer, or getting them published, or getting them safe and sober through Hell’s Angels stag parties.

That’s when I completely blew it. I shared. I shared that if I did have a Higher Power, it was the starter on my car. I shared that I was having trouble believing that H.P. gave a flying fuck about what happened to me. I shared that I was sure that at least four hundred people who worked in the World Trade Center had gone to AA meetings before September 11 and talked about how H.P. was taking care of them, and now they were dead. I mused that maybe this meant that it was OK to be dead, in which case this was no argument against the existence of God. I shared that Walt Whitman said, “A mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of infidels,” so why couldn’t I believe in a God who gave a flying fuck about me? I shared that I was trying and trying to stay sober, but I couldn’t. Was this some fault of my praying technique? I had crouched rather than kneeled that morning; maybe that had screwed things up.

My sharing didn’t go over well. Several people spoke to me after the meeting, looking at me out of the corners of their eyes. One said I seemed “defiant.” Another advised me to “keep it simple.” Mary got a ride home with someone else, and Patrick C. gave me a ride to the garage in his Cadillac Seville. Patrick annoyed me at meetings by talking a lot and by calling himself a “very grateful recovering alcoholic” every time he shared. He and Mary were the two people in the whole program who bugged me the most.

At the garage, I noticed that my mechanic’s wife, who was helping to answer the phone, had a cast on her ankle. She had broken it in a fall. This meant she might have Percocet at her house; I knew where they lived and made a mental note to check this out. In the meantime, I went to great lengths to appear charming and lucid.

On the way home, I stopped by my mechanic’s house and tried the door; it was unlocked. In the bathroom, I found only codeine cough syrup, of which I took a few slugs. I was heading for the kitchen cabinet when I heard a car in the driveway and saw their seventeen-year-old daughter coming home from school. There was nowhere to hide. I waited for her to find me, then mumbled something about leaving a note regarding my starter. She looked at me out of the corner of her eye.

I went home, drank the rest of the wine, and felt human for about thirty minutes. I called my sponsor and talked to him about my problems (not mentioning the wine and the codeine). Then I made dinner, tried to watch TV, came down off my paltry high, and felt incredibly bad. I realized that I never felt this bad when I was trying to get sober, even after weeks of abstinence. I downed some tranquilizers I had stolen and went to bed at seven. My husband was concerned, but I told him there was nothing he could do. I felt like cockatoo crap and just had to sleep.

I couldn’t sleep, though. I was in agonies of recrimination. I was a weevil, a leech, a chigger.

As I began to drift off about 9 P.M., I could think of only one thing that comforted me: Perhaps the boil on the man’s ass really was connected to the attack on the Pentagon; perhaps the edges that we see, the boundaries that define what we call the world, are fused into one seamless unit too large for us to envision. This would mean that all the bad and good are mixed up, and it’s too complicated to assign certain amounts to each person — so complicated, even God, if there was one, couldn’t be bothered to do it.

I also reflected on the laws of probability, which dictated that there were undoubtedly people as rotten as me who had gotten sober, so I might as well try again the next day.

Then I remembered that I hadn’t prayed, so I got out of bed and, rather furtively, kneeled with my hands on the covers. I was really tired by now, so I whispered, “God, if you’re there, I’m here,” and called it a night.