If you want it bad enough and know the right people, you can get anything you want in prison — for a price. The currency of choice where I am incarcerated is stamps. For two first-class stamps you can buy a cookie stolen from the kitchen. For five you can have your laundry washed and folded. For a full book of twenty you can get a hand-rolled cigarette made from the used chewing tobacco that the guards spit into the trash.

In the prison economy I am lower-middle-class. I don’t have three or four ex-girlfriends who send me money, but I do have friends and family who support me, and I earn nearly twenty dollars a month as a chapel orderly.

I try not to spend my limited funds too freely. I don’t buy much from the kitchen, but there is one temptation that I can’t resist: cinnamon. At home it is my partner’s favorite spice, and all of the cookies and muffins I baked for him were pungent with it. I would go to a specialty store and purchase cinnamon imported from Vietnam for five dollars an ounce. In here four stamps gets me a full sandwich bag of cheap cinnamon that’s probably packaged in one-pound containers, but when stirred into my coffee or my oatmeal, it still makes me think of him.

Because you can’t buy it at the commissary, cinnamon is contraband. During a shakedown, if a curious guard should take the time to sniff the contents of that bag in my locker, my stash would be confiscated, and I would have to wash a few windows as punishment. But for the brief thrill that I get when I take that first sip of coffee with cinnamon, it’s worth the risk.

Paul J. Stabell

Ashland, Kentucky

I was seventeen. Reed was fifteen but looked much older. I hadn’t had much sexual experience, just a handful of necking sessions with boys who didn’t seem to know what to do with their tongue once it was in my mouth.

Reed was not my usual type. In addition to his being younger and (I thought) less sophisticated than I was, we had different backgrounds and interests. He got in trouble a lot with his parents and at school. He smoked on the sly, ditched classes, and cursed like a truck driver. But he also had wavy hair, perfect teeth, baby-blue eyes, and an ass that looked great in Levi’s. He taught me how to masturbate him to orgasm while he did the same for me, often standing up in the dusty garage of an old, abandoned house. His manner was rough. He might order me to “take off your panties before I rip them off.” He must have known the effect this had on me. I told Reed to keep his mouth shut about our trysts, but his friend Ben smirked every time he saw me, so I think he knew plenty.

Reed was a jerk most of the time. He had little respect for anyone, especially authority figures. He wasn’t even that nice to me. My best friend, Pam, the only one I told about Reed and me, thought I was making a big mistake. I knew it was foolish to be infatuated with someone less mature and outside my social circle. (I was a snob in those days.) My brother despised Reed, referring to him as “the uncultured swine from down the street.”

Every time Reed and I finished a groping session, I’d tell myself it was the last. But my body betrayed me whenever we got close. If our eyes met on the bus or in the school hallways, and he mouthed the words Meet me tonight, I’d always nod yes.

I am now alone and in my forties and haven’t seen Reed in many years. Every now and then at night, before I fall asleep, he crosses my mind, and my hand wanders between my legs in an attempt to re-create the heady sensation of that first thrill.

Kathleen

San Diego, California

Charlie and I met one Saturday in a park downtown. I went there as a volunteer to hand out sandwiches, and he came to eat. After I gave him his sandwich, he pulled a near-empty billfold from his back pocket and produced a coupon for a free turkey. “I want to give something back,” Charlie said.

I redeemed the coupon that afternoon and brought the frozen turkey to the soup kitchen. The next time Charlie came there to eat, I took him back to the freezer to show him the bird, which would feed thirty people.

I got in the habit of talking to Charlie on Saturdays in the park. He’d once had a good job loading trucks at a food-distribution company, he told me, but then it had shut down. “I’m depressed,” he said, whiskey on his breath.

During the week I started walking through the park on my way to work. I’d often see Charlie on a bench by the goldfish pond. “How’s it going, Charlie?” I’d say. “Hang in there.”

One morning, wrestling with my usual angst about my life’s purpose, I sat down with Charlie.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

“I’m depressed,” I said.

His eyes widened. “You?”

“Yeah,” I said.

“When I’m sad, I sit here and watch the pond,” Charlie said.

I accepted his invitation. While we sat on the bench, and I became late for work, a great blue heron circled the pond and landed in the shallow water at our feet.

“You made my day,” I said to Charlie.

He grinned. “Glad I could help.”

Amy Malick

Hartford, Connecticut

Don’s station wagon was large enough to fit four teenagers comfortably across the back seat. My parents reluctantly allowed me to ride with him and the other guys, believing that we were just going to the movies.

Off we went, six suburban teenage boys relishing our new freedom. Don drove aimlessly while we laughed and spoke of school, sports, and girls. As it began to get dark, we found ourselves in a neighborhood that, had we not been so naive, we would have avoided.

“Is that a hooker?” someone said.

The woman was skinny, sickly looking, and wet, as it had been raining lightly. She stood in front of a run-down house with a collapsed porch a few blocks from the city’s once-thriving downtown.

Don pulled up alongside her and asked her how much for a blow job.

“Thirty-five dollars,” she said. And before anyone could respond, she was in the car, and Don was driving away. Tim moved to the very back to make room for the woman, who directed us to a dark alley a few blocks away.

Once we’d stopped, the prostitute climbed over the rear seat to join Tim. The five of us cheered him on while she pulled down his pants. I remember the confused and frightened look on Tim’s face as this stranger went down on him. When she was done, she asked if anyone else wanted her. Don told her to get out, then handed her only a twenty-dollar bill. The woman screamed and pounded on the car as Don pulled away.

I caught a glimpse of Tim’s face in the yellow glare from the streetlights and saw tears in his eyes. There was no laughing or talking as we drove home, just the sound of the car’s tires splashing through puddles in the street.

Name Withheld

Not too long after I moved to Macedonia, my friends introduced me to a local tradition called “proshetanje,” a late-evening stroll through the streets in which most of the townspeople participated. We’d circle the main square two or three times while I practiced my minimal Macedonian and enjoyed watching friends greeting one another, girls gossiping, and teenagers flirting while their parents looked on in disapproval. I thought it was quaint fun, but my roommate, an American like me, failed to see the appeal. She said parents shouldn’t keep their children out till eleven at night, and they walked too slow to get any exercise, and they weren’t drinking, so what was the point?

One night when my Macedonian friends stopped by to pick me up for proshetanje, my roommate expressed her disdain. One of my companions curtly told her, “Look, we’re a poor country. Unemployment is 40 percent. We don’t have the money to eat meat every meal and go to bars every night. This is our cheap thrill.”

More than a decade later my boyfriend is a poor full-time student, and most of my salary goes to pay our living expenses and my debts. Our friends frequently invite us to join them for happy hour or a show, but we can rarely afford to go. So we have dinner at home, and afterward we go for a walk through our neighborhood. We talk about what we learned or what we struggled with that week. We pet the neighborhood cats and comment on the landscaping and architecture. We never meet anyone we know.

M.C.

Portland, Oregon

My sister, Monica, and I grew up with bare feet and scraped knees. I called her “Moe.” We lived in the country and never went to church, so there wasn’t much need for fancy names, or fancy anything else.

Our neighbor Larry across the street worked at the Farmer Jack Grocery Store. Sometimes he’d give us a ride to school when it was too cold for us to wait outside for the bus. (In Michigan that was often the case.) Larry navigated the icy roads with a cigarette in one hand and the steering wheel in the other, and he made us laugh with his insults.

“Hey,” he’d say, “did your mom have any kids that lived?” Or, “You kids are pretty funny, but looks aren’t everything.”

We always cracked up. It didn’t matter that we’d heard all his jokes ten times before.

Once, Larry brought us a big barrel from the Farmer Jack that had been used for mixing cake batter. Moe and I rolled the barrel to the top of the hill between our house and our uncle’s. Then Moe climbed in, and I counted, “One, two, three!” and pushed my sister down the hill inside the barrel. It thumped over grass and rocks until it came to rest in our front yard. I waited anxiously for some sign of Moe. Finally the barrel wobbled, and she crawled out and walked unsteadily around, laughing.

“You gotta do it!” she said.

We spent the day rolling each other down the hill in the barrel and getting all greasy until we both smelled like cake. I thought nothing could be better.

Kristine Semantel

Wheat Ridge, Colorado

Having a large family, my parents couldn’t afford luxury hotels or fine dining. Most of our vacations were spent camping at the beach and touring mini-golf courses. Once in a while we would pile into the station wagon — the kind with the fake wood paneling and the bench seat that flipped up in back — and drive to the Farmer’s Diner for grilled cheese sandwiches, french fries, and clam strips. We would eat our fill and leave with the smell of fried fish clinging to our clothes and hair.

When my sister and brothers and I were given any spending money (which was rare), we’d splurge on bags of gummy insects or candy cigarettes that puffed powdered sugar when you blew into them. Sometimes we’d go to the bakery and order mugs of mint hot chocolate and cinnamon-raisin toast drenched in butter. If we saved up our money, we could go to the Golden Dragon, a windowless and smoky restaurant with small booths lit by Chinese lanterns. We’d marvel at the giant paper fans and delicate porcelain dolls, and we’d always order the pu pu platter, because we loved saying “pu pu” and seeing the skewers of meat and many dipping sauces arranged around the hibachi grill.

What I enjoyed most was the smell of the other diners’ cigarettes. The scent of a freshly lit cigarette fulfilled some desire in me to be bad and break the rules. I would sit as close to the smokers as I could, waiting for them to strike a match and burn the goodness from me.

Lindsey Scott

Cabot, Vermont

On cold winter nights when I was fourteen, some friends and I would loiter in the first-floor hallway of the housing-project unit where I grew up. We’d chew sunflower seeds and spit the shells on the floor like tobacco juice, which led the project guards to kick us out. We nicknamed the meanest one “Joe the Cop.”

One night we were standing outside the building when it began to snow, and a girl a few years older than us walked by wearing a pair of brown Girl Scout shoes that looked several sizes too big. All she had on for protection against the weather was a dress and a thin, flowered cardigan. Her face was blank, almost expressionless.

“She’s a retard,” one of us whispered.

We coaxed her into the hallway, where we tried to impress her in various ways. She said her name was Chrissie, and that she was running away and hadn’t eaten all day. No one asked from where — or from whom — she was running.

Suddenly the building door opened, and Joe the Cop screamed, “If I catch you punks inside the lobby tonight, I’m going to report you and your parents to management!”

Our parents would then get a warning letter. Three such letters could lead to eviction.

Back outside, Berk, the unappointed leader of the group, began whispering to each of us individually that we should take our new friend somewhere and get as much “titty” from her as we could. We were all virgins. I’m not even sure I wanted to have sex yet.

The group decided to take Chrissie to Moose Field, a vacant lot where we played baseball and football. Only Pinhead walked away from the action. He came from a churchgoing family and would have no part of what was about to happen. I was torn between wanting to go home, because I felt sad for Chrissie, and wanting to see what would come next.

Berk asked Chrissie if she’d like to go to a beautiful meadow. Chrissie said yes, but also that she was cold and hungry. Someone zipped across the street to his apartment and came back with his sister’s winter jacket. Then we each chipped in a quarter or fifty cents, and we walked to the deli and bought two roast-beef, tomato, and mustard heroes. One sandwich we shared among us, and the other we promised to Chrissie once we got to Moose Field.

There were no streetlights around the vacant lot, so we were hidden from everything but our own consciences. Someone handed Chrissie her sandwich. “You guys are my best friends ever,” she said.

While she ate, the guys took turns groping her. They removed her warm coat and worked in pairs, one boy rubbing her breasts while the other stroked her crotch. I watched, ashamed and curious and vaguely aware that it was wrong.

Sometimes now, when I sit down to practice lovingkindness meditation, I think of Chrissie and how I sat and witnessed her exploitation. I wish that I could tell her I am sorry.

Barry Denny

New York, New York

Growing up, I always behaved well, studied hard, and generally did what I was told. I didn’t drink or do drugs or lie to my mom or sleep around or get bad grades. I worked several jobs to put myself through college and graduated with honors.

After college I took a job as a middle-school teacher in an under-resourced school with underperforming students. I had no idea how to be an effective teacher. I couldn’t stay organized, and my classroom-management skills were shaky at best. I was proud of the gains some of my students made, but by the end of my fourth year all I could think about was how to get out. I wanted to go someplace far away and forget my students’ slim chances for success in life, the credit-card bills I couldn’t pay, the friends who were getting married or having babies, and most of all my heartbreak over losing the man I’d wanted to marry.

I resigned my position, let go of the lease on my apartment, sold all my furniture, and bought a one-way ticket to Mexico City. I eventually settled on the eastern coast of Mexico, teaching English at a private school there. It was easy work, and for the first time I had the freedom to do whatever I wanted.

It turned out that what I wanted to do was waste time. I had long conversations with taxi drivers and waiters and strangers at cafes. I got high for the first time and after that smoked pot whenever I pleased. I flirted and had one-night stands with the boys who pressed their bodies into mine at discos. I ate sticky pan dulce each morning, to hell with calories. I passed many afternoons napping or curled up in bed reading. I stayed up late into the night dancing and drinking, and the next day I taught while hung over with a wink from my boss, who had been pouring me shots of tequila the night before.

I condensed a lifetime of cheap thrills into eight months in Mexico. All those short-lived pleasures taught me to treasure people as they are, not as I want them to be, and to live in the moment without worry. I realized that I could let happiness instead of depression swallow me up, that joy could come as fast and intensely as pain.

Mandie Stout

Santa Cruz, California

Eight and a half years ago I began an affair with a man I had known in high school. He was charming and handsome, and we would rendezvous at cheap motels, drink cheap wine, make love, and talk about how we had finally found our soul mates. I recklessly threw myself into the relationship, risking the safe life I had created, including a loving husband, a house, two cars, and a secure job.

I had always been a “good girl,” but for the first time I was doing something bad, really bad, and only I and the man I was doing it with knew. Sometimes I would listen to my girlfriends complain about their husbands, jobs, and kids, and I would smile to myself and think about my enormous secret. I also lived in fear that someone would find out and my life would be ruined, but that only made the affair more thrilling.

I eventually left my husband to marry my lover. We’ve been married for almost seven years, and those motel rooms and bottles of wine are just a memory. We’ve settled into a comfortable existence with a house, two cars, and secure, well-paying jobs. Our marriage is fine, although we rarely use the term “soul mate” anymore, and our fights usually stem from lack of trust. The motels and wine may have been cheap, but I’m paying for them now with my self-esteem. And did I mention the guilt?

Name Withheld

Italian is the language of my ancestors, but I’d never learned it for a variety of reasons: no time, no patience, no guts. Then, two months ago, in a moment of courage, I signed up for a beginner’s Italian class at a local coffee shop.

Tonight is the final session of my class. As I wait for it to start, I say “grazie” over and over under my breath between sips of my (very Italian) cappuccino. I make sure to really exaggerate the r. It sounds beautiful to me. Because the Italian language shouldn’t be whispered, I say “grazie” again, louder this time and with even more emphasis on the r. I look around to see if anyone has heard, and I sort of hope they have.

Most of the other students are older women preparing for a trip to Italy. Because of my work schedule I can’t travel, though I long to go and walk the same ground as my relatives and experience firsthand the rich traditions. Each time I come to class, I feel more connected to my mother, who was born in Italy, and to my grandparents.

“Buona sera a tutti,” our instructor greets us as the class starts. For the next hour and a half, with each phrase I speak, I feel sexier, more dramatic, more Italian. For the price of a fifteen-dollar textbook and a three-dollar cappuccino, I’ve traveled to Italy.

Jennifer Orlando

Grand Ledge, Michigan

I work for a senior engineer who is fluent in Spanish and has traveled all over South America, including the slums of Lima, Peru. Recently he declared that we, his middle-class co-workers, were all living in a cocoon, and if any of us wanted to see what life was like for others, we should take a trip down Albuquerque’s Central Avenue on the Route 66 bus. I decided to do just that the following Saturday.

I admit that I boarded the bus with some trepidation. Every three blocks the age, race, and background of the riders seemed to change: young black and Latina women with their children; middle-aged white men wearing threadbare clothes who limped to their seats, looking much older than their years; old Latino men in cowboy hats and leather jackets. At one stop Asians piled on until the bus was standing room only. People talked freely to strangers and acquaintances alike, and every single person who exited shouted, “Thank you,” to the driver.

I got off downtown, where choppers and lowriders cruised the avenue. I saw a billboard in Spanish asking for help to stop human trafficking. I passed the office of A Million Bones, whose sign asked for student activists to help stop genocide worldwide. I heard a down-and-out young woman screaming at her small child to shut up, and I saw people thoughtfully intervene on the child’s behalf.

On the bus ride home, the woman seated behind me shouted that she needed to borrow a cellphone, and a craggy, handsome man with a cigarillo hanging from his lip offered his. After she made her call, the woman told the man that she had once been beautiful, but crack had ruined her looks. She mentioned several times how cute he was. The man gave her a few bucks and said that he had already handed out twenty dollars that day. The woman said she didn’t intend to take his last dollar, and he replied, “You think I’d give you my last dollar?” They laughed and talked about getting by, and when he exited the bus, she thanked him again.

What had I been so afraid of?

Eleni Otto

Corrales, New Mexico

My ninety-year-old grandmother always says that nothing comes for free in this world, but she insists that you can still find a bargain. Her one-story bungalow is crammed full of TV-commercial gadgets, Macy’s one-day-sale items, buy-one-get-one-free bric-a-brac, and other trinkets and tchotchkes that she has succumbed to purchasing.

It’s a thrill for her to see a commercial for a “genuine caquelon” with long-necked forks for a measly $19.95 that she can order right from her La-Z-Boy. Never mind that twenty dollars is too much for a cut-rate tin fondue pot. Perhaps a better deal is the turkey breast for only five cents a pound, which is now buried in her freezer. It wasn’t really bought to be eaten but because it was such a steal, just like the ten-cent nail polish in neon colors, the cardigan with one button missing and half a seam coming out, and the ten-pound box of pickled asparagus. She can describe the moment she purchased each of these items at great length: a mile-long wait at the checkout counter, a last-minute look at the receipt that saved an extra dollar, a double coupon, and, best of all, the item that was mispriced and was therefore free of charge.

My grandmother’s love of cheap goods has become a very expensive habit.

J.O.

Houston, Texas

I was a twenty-four-year-old single mother when I received my BA in theater. It was immediately clear that my theater stipends and the barista job I’d held while attending college were not going to keep my toddler and me afloat for long, so I got a full-time job as a bank teller.

On my first day of work my grandfather died of a heart attack. He had been the strongest male role model in my life, and I was devastated. I flew back to my hometown that same evening. In the days that followed, my family and I comforted one another and cleaned the inside of Papa’s small trailer home.

My bereavement leave at the bank passed quickly, and it was soon time for me to return to my new adult life. On the morning of my departure my grandmother pulled me aside and gave me a twenty-dollar bill, the only money Papa had on him when he died. I studied it hard on the plane ride home, noticing a burn mark in the center and the careful creases where he’d folded it. I wondered if the burn had come from one of his cigarettes and imagined the bill had been tucked away in his wallet for a long time.

My days at the bank were tedious and long, and my daughter was not sleeping through the night. I needed something to keep me alert. There was an espresso cart right outside the bank lobby, but I had yet to receive my first paycheck, and the only currency I had, besides a large sum of food stamps, was Papa’s twenty-dollar bill. By the third day I had convinced myself that my grandfather would have considered it his pleasure to take his granddaughter out for coffee one last time. So I headed through the glass doors on my break and ordered that long-anticipated nonfat latte with extra foam. But the moment the barista took the bill from my hand, I felt sick inside. How could I part with my deceased grandfather’s last twenty dollars for an overpriced cup of coffee? I tried to savor my drink in his honor, but all I could taste was shame.

I’d been back at my station for just a few minutes when the barista hurried in and walked straight up to my window to ask for change. He handed me five bills, among them Papa’s creased and burnt twenty. I calmly placed it aside in the cash drawer, where it remained for two years until I finally bought it back on my last day at the bank.

Twenty years later that bill sits in a tin box atop my dresser, a monument to my grandfather and to the time in my life when a two-dollar latte was not a cheap treat but an expensive indulgence.

M’Lissa Hayes

Seattle, Washington

I was a nun for twenty years and wore a habit at all times, whether I was cleaning toilets or lighting candles on the altar. I never minded, except for one day on the city bus when a little boy pointed to me and said, “Mama, is she a real witch?” (This was in Oklahoma, where Catholics were scarce.) I grew hot with embarrassment and felt a fervent desire to be able to move inconspicuously in public.

When I told my best friend at the convent what had happened, she suggested we borrow some lay clothes from the donation box at the high school where we both taught, put them on, and go to town. I was hesitant at first but also thrilled by the idea.

Two hours before the rising bell on the appointed day, we unlocked the school building, changed into lay clothes in the girls’ bathroom, and studied our unfamiliar reflections in the mirror. At best we looked dowdy. The outfits were ill fitting, and our scissor-cut hair was unstyled. But our legs were bare. We giggled with nervous excitement.

In town we walked up and down Main Street, and no one gave us a second glance. We went into an all-night diner and took turns sipping a cup of coffee. How liberated we felt! This was living life on the edge.

Judith O’Brien

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

“Can you put these in for me?” my friend Kellie asked, holding up two earrings.

It was easy to push the cubic-zirconia studs into Kellie’s earlobes, as she had no hair to move out of the way. Just twenty-one, she was undergoing chemotherapy for bone cancer. But tonight she, my friend Julie, and I were going out for dinner and a movie, and we weren’t going to let a mid-December rain dampen our spirits.

At the theater we pulled up to the glass doors and rolled Kellie’s wheelchair down the ramp. In the lobby we bought her popcorn and soda that we knew she wouldn’t eat and went with her into the theater to watch a movie that I cannot remember.

Julie and I had known Kellie since she was a child. I’d attended her confirmation and graduation parties. She was a kindhearted girl and more focused on other people than on herself. Anytime I saw her, healthy or sick, she’d ask, “How are you?” Kellie was going to be a social worker like her parents. In high school she’d given up family beach vacations to build housing for the poor in Haiti.

Kellie nodded off during the movie, but she kept bouncing back up to try to be normal. She was determined to have fun on this crappy, dreary Sunday.

By the time the movie let out, the rain had become a downpour, and we drove to a Mexican restaurant and ordered four unhealthy appetizers, knowing Julie and I would do most of the eating. Halfway through her piña colada, Kellie let her eyes close again. When her head dipped down, I could see the large tumor rising on the top of her head, dusted with blond peach fuzz.

As it turned out, that was the last crappy, dreary Sunday I spent with Kellie, the last movie she saw, the last time she ate Mexican food, and the third-to-last Sunday of her life. What I wouldn’t give to do it all over again right now. Best forty bucks I ever spent.

Garland Walton

Fairfield, Connecticut

When I was in high school, I wasn’t as healthy or fit as my friends. I later learned that my weakness was the beginning of muscular dystrophy, but then I knew only that they were all stronger and faster than I was.

One Friday night my friends and I decided to grab some beers and explore the railroad tunnels near the school, which were said to be a meeting place for devil worshipers. As we arrived at the tunnels, a train came snaking around the bend.

“We should hop it!” my friend Kevin said.

We all agreed that this was a great idea, never mind that no one knew where the train was heading. Being the slowest of the group, I reached the tracks last. My friends had already jumped aboard, and the train was picking up speed and entering the tunnel. I was running alongside a boxcar, desperately trying to grab the iron handle to the ladder. After two failed attempts (one almost resulting in my decapitation) I pulled myself up right before the boxcar entered the tunnel. I held tight to the ladder, my back inches from the tunnel wall, the wheels sparking on the old rails below me.

Then the train rocketed out of the tunnel, and I saw my friends on the ground, screaming for me to jump. So I did. It was like being tossed out of a moving car at fifty miles an hour. After a considerable amount of time my body rolled to a halt. As my friends came running, I rose to my feet and let out a yell, uninjured except for a few scratches. Their hoots and howls filled the night air.

I was happy to be alive, but I was more thrilled to have proven to my friends that I could hop that train with them.

Peter J. Gerrity

Bayonne, New Jersey

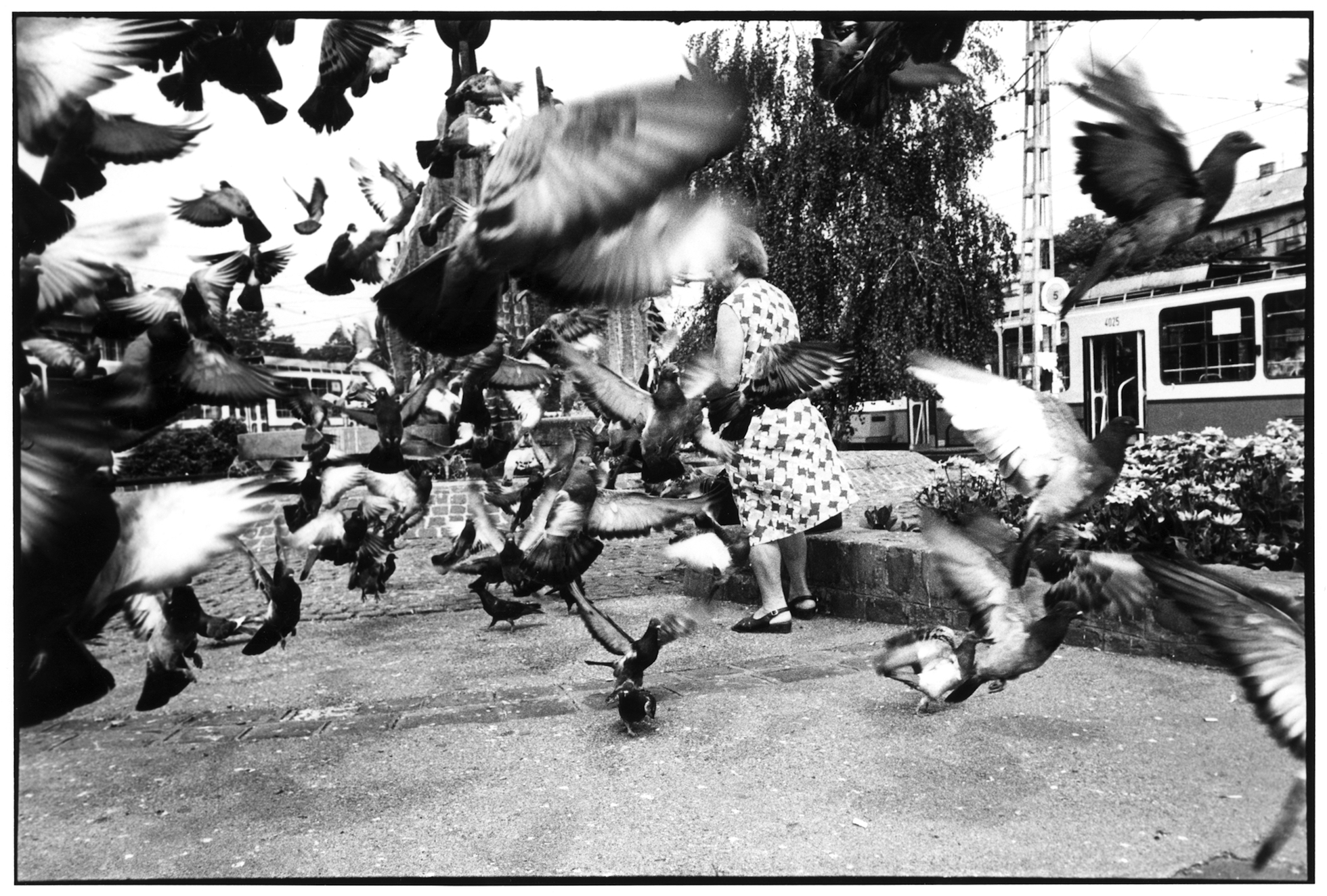

The pigeons came from every direction, their flapping wings drowning out the noise of traffic and crowds. The bright sunlight lit their iridescent feathers as they landed at our feet and on our arms, shoulders, and laps.

This was 1963 in downtown San Francisco. My buddy Doug and I had gone to Robinson’s Pet Shop on Maiden Lane, the inspiration for the pet shop in Hitchcock’s thriller The Birds, and bought two five-pound bags of premium birdseed. Then we’d walked to Union Square, found a relatively quiet place to sit, and opened the bags.

As the pigeons congregated around us, we laughed and tossed out seed. When we ran out, we decided to go home. Slowly and carefully we tiptoed our way through the mass of birds and walked down Powell Street, not realizing at first that we were leading an army of pigeons. Shocked pedestrians stepped off the sidewalk and into stores to avoid this bizarre parade. Even after we saw the pigeons, we pretended not to notice.

At the corner of Powell and Market, Doug and I boarded the streetcar to the west side of the city. I heard cooing sounds and saw that Doug had a beautiful gray-and-white-speckled pigeon tucked away in his jacket. We got some very strange looks from the other passengers, but we maintained our composure.

We set the pigeon free just outside of the west-portal tunnel, and it headed due east, probably back to its flock. Not long after that, we saw signs posted at Union Square: “Do not feed the birds.”

Keri Jenson

Oakland, California

When my best friend and I were high-school seniors in 1959, cigarettes were only twenty-five cents a pack. One day we decided to swipe a pack of her mother’s Marlboros and see what smoking was all about. To top it off, we were going to go to a cocktail lounge in the city and order a drink.

We dressed to look adult and worldly and took the bus to downtown Seattle, the stolen cigarettes tucked safely into my purse. Sauntering into the Olympic Hotel, we settled into seats in the lounge, ordered drinks, and lit up. As the alcohol rushed into our systems, we attempted to smoke like seductive women, or at least not amateurs. We couldn’t look at each other for fear we’d burst into laughter — or tears, because it tasted so terrible. Try as I might, I couldn’t inhale. But we thought we pulled it off, holding our cigarettes gracefully, smoke circling our heads.

The next morning our mouths were dry, and our hair smelled stale and smoky. We weren’t eager to try that again anytime soon.

Many years later I watched my father unhook himself from his oxygen tank and go out to his backyard for a smoke. He struggled to take a breath because of emphysema, but he couldn’t kick his nicotine habit. I figure that twenty-five-cent package of Marlboros kept me from a similar fate. Pretty cheap if you think about it.

Eileen Hosey

Juneau, Alaska

My husband and I sleep in separate bedrooms and basically live as roommates. He has withdrawn so far from our family life that I consider myself a single parent.

After the kids are in bed and I’ve crawled under my cold covers, the loneliness catches up with me, and I imagine I’m lying beside my college boyfriend. I tuck a pillow against my back and pretend he’s there with his arms around me, stroking my hair. Sometimes I talk to him in my head. He always listens carefully.

I hope someday my husband and I can work through our difficulties, but for now spooning with my pillow and remembering my past get me through the night.

Name Withheld

My friend Isaac and I are drinking after work at a Mexican restaurant with John, who is twice our age. We met him a year ago when he led us on a bungee-jumping excursion. Since then we have regarded him as our mentor in adventure.

Tonight John has a new thrill for us. “It wouldn’t be a big stunt,” he says, “but I’ll bet you it would be scary as hell!”

A half-hour and two gin and tonics later I find myself standing on the top beam of a wooden swing set in a vacant park playground. I have a harness strapped around my waist and another around my chest. Both are hooked to approximately six feet of rope that’s been tied to the beam I’m standing on. My balance wavers, and I squint to focus on the wood beneath my feet.

John, Isaac, and I measured the rope before I clambered up here and determined that, when I dive off, my head should avoid the ground by about six inches. We also bounced on the wood chips covering the ground and agreed that they were “soft.” Now that I am standing on top of this swing set, however, I don’t find soft wood chips all that reassuring.

John and Isaac scramble to find the best camera angles for a photo. Satisfied with his position, John looks up at me and asks, “Are you ready?”

I take a moment to evaluate the risks and tug on my rope a couple of times. It seems secure. Fuck it, I think.

“I’m ready,” I say, but my voice wobbles with uncertainty.

“Remember, you need to leap straight out so your rope stays tight,” John says.

“I know. I’m ready,” I say, with a little more confidence this time.

They count down, and the hairs on the back of my neck prick up.

“Two . . . one . . . jump!”

I leap outward, and the rope stays tight. Just before I make contact with the wood chips, the line whips me away and up toward the other side of the beam. I spin violently at the end of the rope until the swinging and spinning level out, and my body just hangs like a rag doll. I’m completely relaxed from the rush of adrenaline, more present in the moment than I’ve felt in a month. Funny how the closer you come to death, the more alive you feel.

Edwin Bobrycki

Twain Harte, California

As a (very) young adult in the late sixties, I was influenced by Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and determined to live a life worth writing about. Not that I actually wanted to write, but my life, I believed, should be noteworthy. To that end I made a list of experiences that I thought I should have, including spending time in jail, becoming enlightened (whatever that meant), and parachuting.

Then one day I fell from a second-story porch and injured my left kidney and my spleen beyond repair. The organs were removed, and I nearly died. When the doctor sat me down to discharge me, he told me that people live long lives without a spleen and that my remaining kidney would grow to one and a half times its normal size and provide all the filtering I would need, but he cautioned me never to participate in any risky behaviors like sky diving.

Relieved, I crossed that experience off the list.

Years later I did an internship in a jail and led guided visualizations for the female inmates, which was the closest I came to doing time or finding enlightenment. But I gave up trying to live a remarkable life the day I looked around me and realized that there was not a single person whose life was not worth writing about.

Beryl J. Polin

Carmel, New York