The Seed was a controversial youth drug-rehabilitation program that flourished in south Florida when I was a teen in the early 1970s. Founded by former comedian and recovering alcoholic Art Barker, it was modeled after adult treatment programs and administered by unlicensed staff. The Seed utilized coercive techniques such as aggressive confrontation, intimidation, verbal abuse, sleep deprivation, and restricted access to the bathroom to tear down a teen’s sense of self and replace it with the ready-made identity of a “Seedling.”

The Seed was highly publicized, and the attention eventually proved destructive to the program. In 1974 the U.S. Senate published a study that accused the Seed of using methods similar to North Korean communist brainwashing techniques. The bad press, in conjunction with legal pressure from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the drying up of federal funds, forced the Seed to scale back its operations dramatically. By the 1980s it had shrunk to a fraction of its former size and was officially admitting only voluntary clients. The Seed endured in this diminished capacity until it finally closed in 2001.

Today hundreds of similar programs are in operation throughout the United States and abroad. Some are even run by former Seed staffers. By most accounts, these programs are much harsher than the Seed.

I was in ninth-grade science class one afternoon in October 1972 when a note arrived summoning me to the dean’s office. My older sister, Judy, was already there. “Mommy needs us,” she said. I could tell by the apprehension in her eyes that she knew nothing more. I imagined my grandmother might be very sick, perhaps even dying.

My sister and I sat in front of the school until our parents pulled up. There were two other adults with them, a couple they introduced to us as “Mr. and Mrs. J.” I was relieved, because I could tell from my parents’ jovial attitude that nothing terrible had occurred. My sister and I got in the back seat. I didn’t think it unusual that Mrs. J. took the window seat next to my sister and Mr. J. got in on the other side, next to me; my mood had lightened considerably by then. Our mother encouraged us to try to guess where we were going. After a few minutes she gave my sister a hint: “Remember that news story we saw on TV the other night?”

“Oh,” my sister replied. “The Seed.”

I had heard of the Seed. It was a drug-rehabilitation center. My experience with drugs consisted of having smoked marijuana about ten times. My parents didn’t know this for a fact but were concerned about the company I was keeping and my disrespectful attitude toward them. Judy was also a source of worry to them because of her more blatant drug use and rebellious streak. I imagined they were taking us on a tour of this place to scare us. I mentioned to my father that I had a chess-club meeting that afternoon and did not want to miss it.

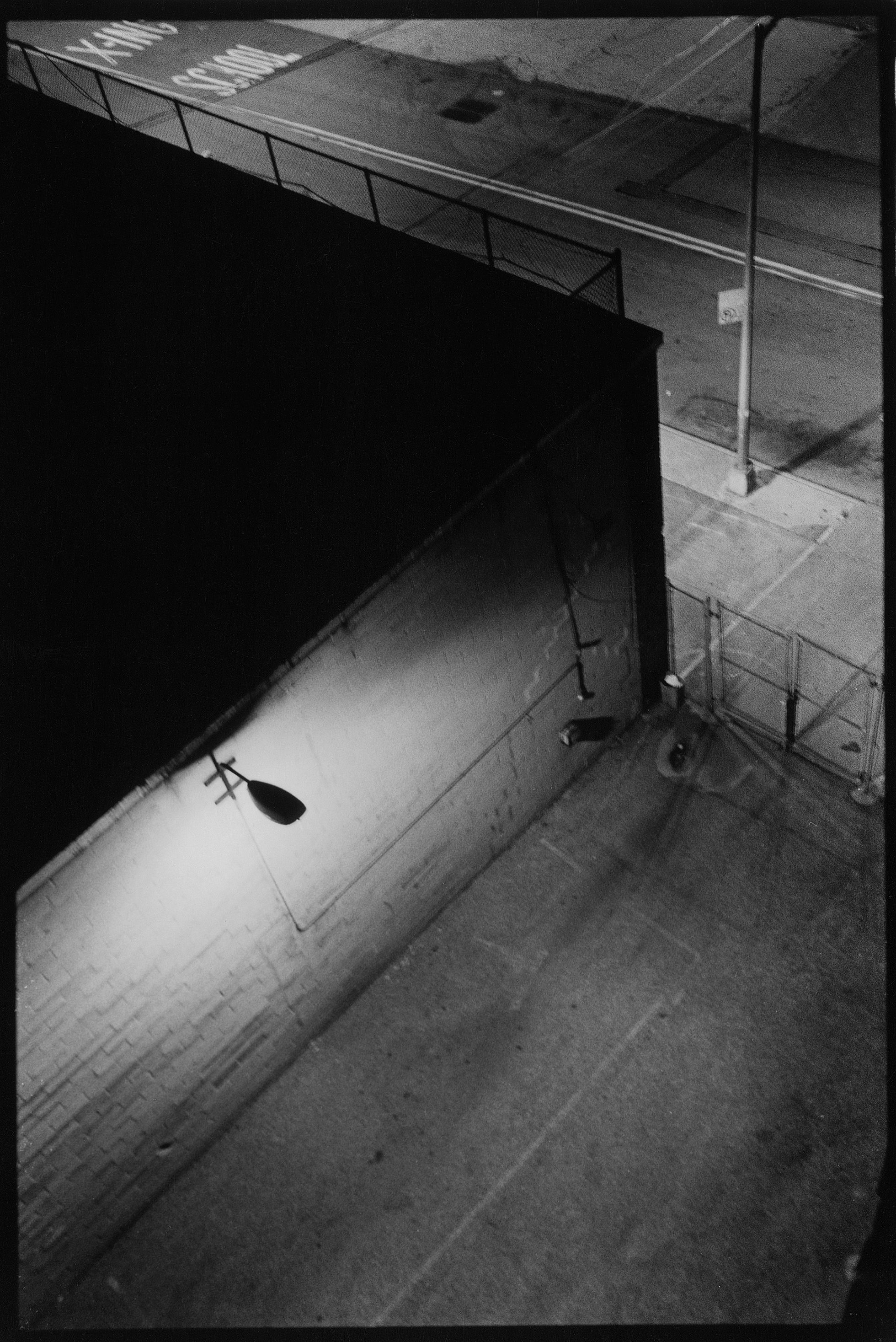

We arrived at an old warehouse surrounded by a chain-link fence. Two young men sitting on chairs by the driveway stopped our car briefly, then let us park. In the reception office a middle-aged woman named Vera sat down to talk with us. She addressed my sister first, asking her age, grade in school, and the kinds of drugs she had used. My sister answered frankly. There followed a peculiar exchange in which Vera made insulting remarks about my sister’s character and lifestyle, for no apparent reason other than to goad her. Judy’s reaction was first astonishment, then hostility. Meanwhile young people came in and out of the office, calling out greetings to Vera or bringing her messages. These were not kids receiving treatment but Seed staff members, I’d later discover, all of whom had been through the program. After each interaction Vera would say in a singsong voice, “Looove you.”

Toward the end of her prickly conversation with Judy, Vera revealed that my sister and I would be staying at the Seed for a while, and that we had no choice. I was shocked. We were not “druggies,” as Vera charged. I had no concept of what was really going on, and was sure we would get out soon, once the Seed realized its mistake. I even said to my sister, who was upset, “It’s OK. We’ll just agree with what they say, and then we can go.”

When Vera finally got around to me, she asked how old I was (fourteen) and what drugs I had used. I told her just pot. “Don’t bullshit me,” she said with a sweet, contrived voice and an intimidating stare.

While Vera was doing my intake, my sister had to use the bathroom. She was accompanied by a chaperone, another girl her age. A few minutes later a female Seed staff member approached my parents and informed them that my sister’s attitude was rotten. She explained: “We have a rule here that when a newcomer goes to the bathroom, someone must be there to hold her hand. Your daughter didn’t accept this, and she swung at the other girl.”

My sister and I were taken to separate rooms to be searched. I had to strip, and my keys and money were turned over to my parents. Then Judy and I were led to a long, stark, cement-walled room where about three hundred young people, ranging in age from twelve to their midtwenties, sat in rows of folding chairs. They all faced a young man seated on a high stool and holding a microphone. The boys and girls — whom the man referred to as “guys” and “chicks” — were separated by a wide aisle down the middle of the room. (Males and females were always separated at the Seed.) The windows were eight or nine feet up on the walls, and the two doors were guarded by Seed staffers. A sign on the wall proclaimed, “You’re not alone anymore.”

Upon our arrival, the “rap” in progress was briefly interrupted, and Judy and I were made to stand in front of the group to be introduced by our name and the drugs we had done. When it was my turn, the rap leader said, “And this is Marc. He says he’s only done pot.” The group then greeted us in unison with a resounding “Love ya, Judy and Marc!” and we were led to seats in the front rows of our respective sections.

We stayed there until ten that night. At the end of the day’s final rap, the rap leader said, “OK, all oldcomers picking up newcomers, pick ’em up.” The program had no overnight facility, and “newcomers” were not allowed to live at home, so they went home with “oldcomers” who’d been in the program a while and were deemed trustworthy. My first night I went home with Aaron, who was fifteen. I tried to explain to him that I was not a druggie, but he insisted that I was, even if I had smoked pot only once — or, for that matter, even if I just had a “druggie attitude.” When I told him I thought my attitude was fine, Aaron replied, “Listen. Don’t argue with me. Your attitude sucks.” I don’t think he was being mean. At the Seed it was an indisputable tenet that any newcomer’s attitude sucked, and there were only three roads a person could travel after his or her first puff on a joint: prison, insanity, or death — unless he or she was saved by the Seed.

I slept on the floor of Aaron’s bedroom. He had removed the handles from the windows, and he slept with his bed blocking the door. I still felt this was all a big mistake and entertained hopes of getting home soon. The Seed was probably a good place for some people, I thought, but I obviously did not belong there.

As a “Seedling” I lived by a strict schedule. Until the Seed determined you were rehabilitated enough to sleep at home and go to school, you had to spend twelve hours a day at the warehouse. Even after they’d returned to school, Seedlings were required to be at the Seed from the time school ended until ten o’clock at night. In the final stage of the program, attendance was required only three evenings a week, and one day on the weekend.

The Seed day began at 10 A.M. with the “morning rap,” which lasted more than two hours. The rap leader sat on his stool and called on people to stand and “participate.” Everyone who had been in the Seed more than a few days had to raise his or her hand to be called on or else be accused of “copping out.”

There were a limited number of topics for raps. Some were about how you and your old druggie friends had used each other for drugs or money or status and had only pretended to be friends while secretly despising one another. “Honesty” was a standard topic too. Being honest meant admitting you’d been “full of shit” before coming to the Seed, that all your relationships had been “bullshit,” that you had been horrible to your parents, who loved you, and that you’d been a dishonest, insecure, unkind, thoroughly worthless mess.

On my first day the morning rap was on “conning,” which meant parroting the Seed philosophy without really subscribing to it. No one could successfully con the Seed, I learned, because “everyone knows just where you’re at.” Seedlings were so supremely “aware” they could spot a con a mile away. This was when I realized that the Seed was after a different, more fundamental change than I’d imagined. Now I was scared.

Just as bad as conning were “analyzing” and “justifying.” “Analyzing” was just mixing up the facts and making them more confusing. “Justifying” was what you achieved by doing this. You analyzed your past actions to make it seem as if you’d had good intentions, or you analyzed what the Seed was telling you and tried to twist it in such a way that it seemed as if the Seed were wrong and you were right, though you knew in your heart that the Seed was right and you were an asshole. In fact, everyone was an asshole before he or she came to the Seed. Most of us had to proclaim this before the group at least once before we got to go home. Occasionally there were feel-good raps about “love” or “happiness,” which inevitably elicited ecstatic comments about the “vibes” in the room, but even these came back around to how you had never truly been happy when you’d been “on the streets.”

Sleeping during raps was strictly prohibited, though virtually everyone was sleep deprived due to the long days at the Seed, followed by extended carpool rides to the homes of oldcomer hosts and after-hours “rehabilitation” with oldcomers. If you saw someone sleeping nearby, you were supposed to shake him or her awake. Even daydreaming was forbidden. If you looked as if you weren’t paying attention, the rap leader or a staff member would shout, “Hey, get out of your head!” “In your head” was a bad place to be caught at any time. Private reflection and introspection were counterproductive, because they inexorably led to analyzing and justifying.

During raps, a person who’d been unwilling to be “honest” might be “stood up”: made to stand before the group while everyone else took turns saying how appalling he or she was, using name-calling, derision, and profanity. Boys were “twerps” and “pussies.” Girls were destined to become prostitutes if they didn’t shape up.

On my second day a young man named Jerry was made to stand up in front of the group. Apparently he had turned eighteen and had decided to leave the Seed, as was his legal right. A staff member said dryly, “I think we should try to talk him out of it.” One by one, members of the group told Jerry what they thought of him. The boys said things like “If I had met up with a guy like you on the streets, I would have used you for what I could get from you, walked all over you, and then beaten the crap out of you.” The girls emphasized that he was pathetic and ridiculous and unmanly. When the rap leader asked, “How many of you chicks would have had anything to do with a guy like this when you were on the streets?” no girl raised her hand. After the group was finished with Jerry, he was crying and had to beg to be allowed back into the Seed. The rap leader contemptuously told Jerry the precise words to say, and Jerry dutifully repeated them through his tears.

Everyone knew what you were supposed to say in the raps. The trick was to make your testimony sound convincing, lest you be accused of conning or giving “pat answers.” Rap leaders repeatedly warned the group: “I don’t want to hear any pat answers!” This placed us in a double bind: we were expected always to say the same things, but in different ways.

After the morning rap, we sang songs. Most were innocent kids’ songs, such as “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,” but a few had lyrics altered to fit the philosophy of the Seed. For example: “If You’re Straight and You Know It, Clap Your Hands.” And then there was the “Seed Song,” sung to the tune of “Greensleeves”:

The Seed indeed is all you need To stay off junk and pills and weed. You come each day from ten to ten And if you screw up, then you start again.

After the songs came lunch. A line formed at the back of the room, and each Seedling picked up a baloney or peanut-butter sandwich and a cup of Kool-Aid. Sometimes during lunch an oldcomer would introduce himself to the group and say what drugs he’d done, usually expressed as a range: “I’ve done pot to speed.” The Seed placed drugs in the following, somewhat arbitrary, hierarchy: marijuana, hashish, barbiturates, mescaline, LSD, amphetamines, cocaine, and heroin. This was assumed to be the order in which everyone tried drugs. So if someone had done “pot to speed,” he or she presumably had also used LSD, but not cocaine.

After lunch came the afternoon rap, which lasted until three. Then everyone filed into the parking lot for a half-hour of calisthenics. Next the “guys” and “chicks” gathered at opposite corners of the parking lot for gender-specific raps. I cannot say what went on in the girls’ raps, but in the boys’ raps we talked about how chicks used and manipulated us and always had us “by the balls.” (Having had very limited experience with girls, I could not participate too well in these discussions, but I invented things to say all the same.) One frequently delivered pronouncement was “Chicks are so slick, man!” There was also contrite acknowledgement that all we had really wanted from chicks was sex and ego gratification.

At five everyone filed back inside for the hour-long “rules rap.” The first thing the rap leader said each night was “Honesty is our first and most important rule.” The other rules followed in no particular order:

No boy-girl relationships while in the program. The reason was that you had to get straight first before you could have any kind of relationship with the opposite sex that wasn’t “bullshit.”

No old druggie friends or old druggie hangouts. Talking to an old friend was a serious offense, and if someone was caught doing so after returning to school, he or she could be made to start the program over. In fact, a Seedling could be abruptly started over or demoted to an earlier stage for a variety of real or imagined transgressions.

No hitchhiking or picking up hitchhikers. People who hitchhiked or picked up hitchhikers were invariably druggies.

No stopping at the store on the way home if you have newcomers in the car. Convenience stores such as 7-Eleven were druggie hangouts.

No newcomers talking to newcomers. Newcomers were full of shit and had nothing to say anyway. They could only hold each other back by talking to one another.

No automatically moving ahead in the program. Only the Seed could say when an individual was ready to progress to the next stage.

Protect each other’s anonymity. This was pointless, I’d discover, because everyone at school knew who’d been in the Seed.

Supper, which was served with songs before, during, and after, generally consisted of sloppy Joe or dubious chow mein with a cup of Kool-Aid or powdered milk. During the rules rap and supper, those who were back in school were allowed to sit apart from the group and do their homework. At seven came the evening rap, which lasted almost until the end of the Seed day at 10 P.M.

On my third day in the Seed I was called out of the group to speak privately with Gloria, a nineteen-year-old staffer. “As you probably know,” Gloria began, “your sister split this morning.” To “split” meant to escape from the program. Many newcomers attempted to run when they had a chance, but usually they were caught and restrained by physical force. The few who got away had no place to go and were often brought back and made to start the program over from day one. (Judy was picked up hitchhiking by a kind soul who drove her to a voluntary halfway house for girls in Miami called Genesis House. They treated her with compassion there, and she wound up living in Genesis House until she turned eighteen.)

Gloria and I talked for an hour or so. When I tried to explain that I did not have a druggie attitude, Gloria asked, “Have you ever been inside Raiford?” Raiford was the state penitentiary. “It’s an awful place,” she said. “People use you. They use your body.” The implication was that, if I did not get straight through the Seed, I was likely to end up being raped in Raiford. The specter of prison was often held over the heads of newcomers who resisted: “You wouldn’t last very long at Raiford, smartass.”

Needless to say, I did not convince Gloria that I was straight. That night I was sent home with a different oldcomer. Stan was older than Aaron, had been in the Seed longer (three months), and was a really “strong” Seedling. He had other Seedlings besides me staying with him: up to four of us at once, with the help of a second oldcomer. Stan lived with his father in an enormous home in Coral Gables, an hour and fifteen minutes from the Seed. We all slept in two adjoining rooms upstairs. The doors had security locks on them to which Stan alone had the keys.

The relationship between a newcomer and his or her oldcomer host was supposed to be intimate. It was the oldcomer’s responsibility to get the newcomer straight, and to do that the oldcomer had to get to know the newcomer and exploit his or her weaknesses and inconsistencies. Many times Stan screamed at me, “You don’t argue with what I say! You just accept it!” Disputing the oldcomer’s word was a sure sign of being full of shit, not honest, and not “working.” And you had to please your oldcomer if you wanted to go home, since the oldcomer could report you to the Seed staff.

Though we were not supposed to talk about our old druggie lives in any but the most derogatory terms, Stan bragged about his. He would recount all the LSD he had taken, the girls he had bedded, and the smashing parties he had thrown. Of course he’d always add how, through it all, he had been secretly miserable. Although he had been undisputed king of his druggie world, inside he had been suffering. Late at night, when the parties were over, he would throw himself on his bed and cry. He also made sure to point out that he was a straight-A student with a genius-level IQ, lest I think I was smarter than him.

Each night Stan made me write a “moral inventory,” listing all the good things I’d done that day (“I participated honestly in the morning rap about old friends”) and the bad (“I was getting into my head during the afternoon rap”). Then I had to explain my bad points. (“I was copping out of the rap because it was blowing my image of myself.”) My moral inventory had to satisfy Stan before I was allowed to go to sleep. Often he would make me redo it two or three times until it was “honest.”

Stan turned sleep into a privilege that had to be bought for a price: usually a concession in an argument, or a chunk of dignity. Often I would be the last newcomer allowed to retire because I was arguing with Stan over something, like whether I had read Siddhartha, by Hermann Hesse, for pleasure or just to impress people. He vehemently accused me of “playing the heavy-intellectual game.” If I mentioned that I had two good friends, Stan would state flatly that they were not my friends, nor had they ever been, nor had I ever been a friend to them. He insisted that I’d been completely insecure and unhappy before coming to the Seed, and he loved me too much to let me deny it. I resisted giving in on these and other points, but I eventually relented, since my stubbornness only earned me more scorn and rage. It hurt, though, to “admit” he was right.

“What are you thinking?” Stan would often demand without warning, as if it were his right to open my head like a jar full of jelly beans and pick out a thought. Most of the time I would answer him truthfully; he could tell if I was lying, because it would take me a moment to make something up or twist what I was thinking into a more acceptable version. After I’d told him precisely what I was thinking, he would pronounce it bullshit and tell me what I should have been thinking instead. I remember the moment, on the evening of my eighth day, when I realized that I had lost the ability to think matters through, because I had grown so accustomed to having my thoughts intruded upon without a moment’s notice.

The only point on which I did not eventually give in to Stan was my belief that I’d been happy before I’d come to the Seed. I believe it was this refusal that led Stan to comment, on the night before I was finally allowed to go home, “You’ve made some progress, but you’re not even in the same ballpark as being allowed to go home.”

What “progress” I’d made had already cost me dearly. Even if I had been pulled out of the program at that point, I could not have gone back to being the person I had been. I could no longer think clearly and had a reflexive fear of being caught or invaded. Stan’s “What are you thinking?” ploy had done its job.

Stan was a genuine believer in the Seed. Once, after a night of arguing with me, he sighed and said softly, “You know, even though you’re so full of shit right now, I know you’re going to make it. You’ll be another Seed success story.” And I once heard him remark reverently to another oldcomer, “The Seed will change the world. The Seed will be the world someday.” This was the mythology of the Seed, and we were all indoctrinated into it. The Seed would keep growing until there were Seed programs in every city on the globe. The Seed was not just the only drug program that worked; it was the primary source of enlightenment in the world.

On Monday and Friday nights we had “open meetings,” which started at 7:30 P.M. and often lasted past midnight. They were called “open meetings” because parents and other family members were allowed to attend. The parents sat in rows of chairs opposite their children. The Seed’s founder, Art Barker himself, was usually on hand to say a few words of comfort and assurance. Everyone had reason to be happy, he’d tell the parents, because these kids were in the best place they could possibly be. Sure, they might take some bumps and hard knocks, but every one of them was on his or her way to getting straight. And no matter what anyone said or did, the Seed was just going to “keep on saving kids.”

When it was the parents’ turn to speak, the microphone was passed from couple to couple, and they could talk to their child as long as they liked, which is why the meetings lasted so long. Usually they would encourage their kids to “keep working” and tell them they were missed, but once in a while a parent would say something like “We got your message through the Seed that you needed some more clothes and cigarettes.” (Cigarette-smoking was permitted in the Seed.) “Well, we brought your clothes, but we didn’t bring the cigarettes. You don’t deserve any!” Any public censure of a child by a parent was applauded on principle. After all, the kids were there to learn respect.

But what was exciting about the open meetings was that the parents learned at the door whether or not they could take their child home with them that night, and then they revealed the news to their son or daughter in front of the group. The emotional drama was spectacular. Of course there were also those who waited expectantly, meeting after meeting, for the magic words that did not come.

On my thirty-second day in the Seed, a Monday, I was allowed to go home. I walked out the gate that night with one arm around each parent. When we got home, I told them how awful I had been to them, how happy I was that they had sent me to the Seed, and — many times — how much I loved them. There were smiles all around, and I got to eat all my favorite foods to my heart’s content. Best of all, I could take my dog for a walk, play my records, and use the toilet all by myself. The freedom was heavenly, and I cannot say I was unhappy that night. But underneath all the jubilance was a sick feeling. I had said all the things I was supposed to say to my parents, but in my heart I did not feel them. The brand-new son my folks were so pleased with was not who I really was.

A day or two after coming home I wrote a letter to my sister, who was living in Genesis House. I told her about the new person I’d become, and the wrongs we had done to our parents, and how fortunate I was to be in the Seed. I also disparaged my previous relationship with her. Much later I would learn how deeply this letter had hurt Judy, and I would tell her, truthfully, that I hadn’t meant any of it. I’d written it only because I wanted to prove my loyalty to the Seed. There had been occasions when a rap leader had mentioned, or even read aloud to the group, letters that had been intercepted. One girl, whose letters to her boyfriend were read before the group, had been humiliated and then forced to start the program over. I was convinced the same could happen to me.

A week after arriving home I was allowed to return to school. On my first day back, my best friend, George, turned around in his seat, looked skeptically at me, and asked, “Same as you were?”

I smiled an arrogant Seed smile. “A little different,” I said.

“I liked you the way you were.”

“Turn around. I can’t talk to you.” I was afraid I had already said too much. I didn’t know whether there were any other Seedlings in the room.

There were about thirty-five Seedlings in my high school, and later that day I was made a member of their society. Seedlings were supposed to keep an eye on each other, though some followed this directive much more enthusiastically than others. If one of us so much as went missing from the Seedlings’ lunch table in the cafeteria, it was cause for deep suspicion.

I soon decided that George was straight after all. Like me, he’d done little to earn the title “druggie.” A kid had to look straight to other Seedlings, however, for it to be all right to talk to him, and George, whose hair was over his ears, did not meet this criterion. Within a week of being back in school I was in trouble with my fellow Seedlings at lunch. There was no name-calling or overt threat, but everyone seemed genuinely concerned that George was “dangerous.” Hadn’t he been a part of the life I had led before the Seed? How did I know he wasn’t using drugs now? He could be lying to me.

To the credit of the Seedlings at my high school, this incident was never reported back to the Seed. I certainly would have heard about it if it had been. But just the implicit threat was enough. People had been started over for less-serious offenses.

The next day I told George that I couldn’t talk to him. When I reported this to a fellow Seedling, he good-naturedly corrected me: “You should say you don’t want to talk to him. Not you can’t.” So the next time I saw George, that is what I said.

George and I eventually worked out an arrangement in which we talked only in gym class, which was held outside, so there was no chance of another Seedling walking by and spotting us. But our friendship was never the same.

Shortly after I’d been allowed to go home, I was sitting in the large warehouse room at the Seed one evening, pondering the fact that I still believed myself to be different from everyone else in the Seed and wondering what good it did me to feel this way. I could see how the belief was causing me pain, but I could not see how it served me. If there was nothing for me but to be a Seedling, I thought, then I might as well be one wholeheartedly and embrace whatever rewards came with it: being a part of something larger than myself, a member of a self-proclaimed elite; having friends, a community, an identity. Why hold out for some other set of rewards that I had already sold out anyway?

And that’s when I made a strange decision: I decided to become a true Seedling. All the energy I had put into resisting Stan and the others I now directed at myself. I became my own primary oppressor, working to deny and even change my genuine feelings. After all, I’d already betrayed my sister and my friends. One more betrayal would not make much difference.

This strategy worked brilliantly. I moved quickly through the rest of the program and graduated from the Seed nine days after my fifteenth birthday. For a few weeks it was still mandatory for me to come to meetings on Tuesday and Saturday nights, but when I started missing them now and then, no one said anything, and I gradually attended them less and less.

A year after completing the program I was excommunicated from the Seed community at school for talking to druggies, growing my hair long, and showing other signs of having a druggie attitude. And I did use drugs again — many more drugs, in fact, than I had used prior to being in the Seed. My relationship with my parents deteriorated and became fraught with hostility. My grades declined, and I failed classes for the first time in my life.

Within two years all but one or two of the students who’d been in the Seed with me had gone back to drugs and their old friends. Some of my fellow ex-Seedlings were, like me, deeply bitter about the experience, but most were indifferent; they seemed to have gotten over it and wondered aloud why I couldn’t. One or two even contended that it had been good for them: though they had returned to the lives they’d led before, they were now more in control.

Why did I feel so damaged? Because the Seed had forced me to mean things that were not true. I felt I had betrayed everything that was sacred to me, and even if my old friends still thought well of me, I no longer deserved them.

Perhaps some people did con the Seed, but I couldn’t. Maintaining a consistent lie under such stressful conditions was a tall order for an unsophisticated young teenager. Also I saw too many other Seedlings get busted and started over for conning. Whether these unlucky kids had actually been conning or not, I have no idea.

The ultimate consequence of my time in the Seed was an overwhelming self-disgust that lingered for years. Everything seemed a mockery of itself. I fundamentally doubted the authenticity of any conviction — my own or someone else’s. I had acquiesced and adopted the Seed’s judgment for a time, and I could not easily disown it.

In order to see the Seed not as a fundamental frame of reference but as just one tiny, narrow-minded, self-aggrandizing pocket of fear in the world, I first had to forgive myself for the part I had played in my own undoing. I needed to look at the fourteen-year-old kid I had been in 1972 and understand the pressure he’d been under, and feel compassion for the choices he’d made, and accept that he hadn’t been as heroic and invulnerable as he would have liked to be.

When I think now of the power the Seed had over me, I remember a time when I was still a newcomer, and the Seed was trying to obtain a license to open up a branch in Dade County, Florida. A new song was introduced called “When the Seed Comes into Dade” (sung to the tune of “When the Saints Go Marching In”). During renditions of this song, we would all wave our hands above our heads in a hallelujah gesture and sing more and more exuberantly with each repetition of the chorus. And when, in the middle of an open meeting one night, Art Barker strode into the room and announced that the Seed had won its license, I took part in the three-minute standing ovation that ensued. Despite my adversarial relationship with the Seed, despite the fact that I was there unwillingly, despite my general misery, I somehow felt included in the victory.