For the past forty years I have made Vermont my home. I love it here, yet I am compelled to leave every few months with my backpack and cameras and a ticket to some distant place. I travel as simply as I can, with a tent, a sleeping bag, some cooking gear, and small gifts to give to people I befriend along the way. I am drawn in particular to the indigenous peoples of the world and their vanishing customs. They have taught me groundedness, humility, wisdom, and authenticity. I am an old man now, and my hair has turned white, but I feel young inside, in part because of the people I’ve met in my travels.

— Ethan Hubbard

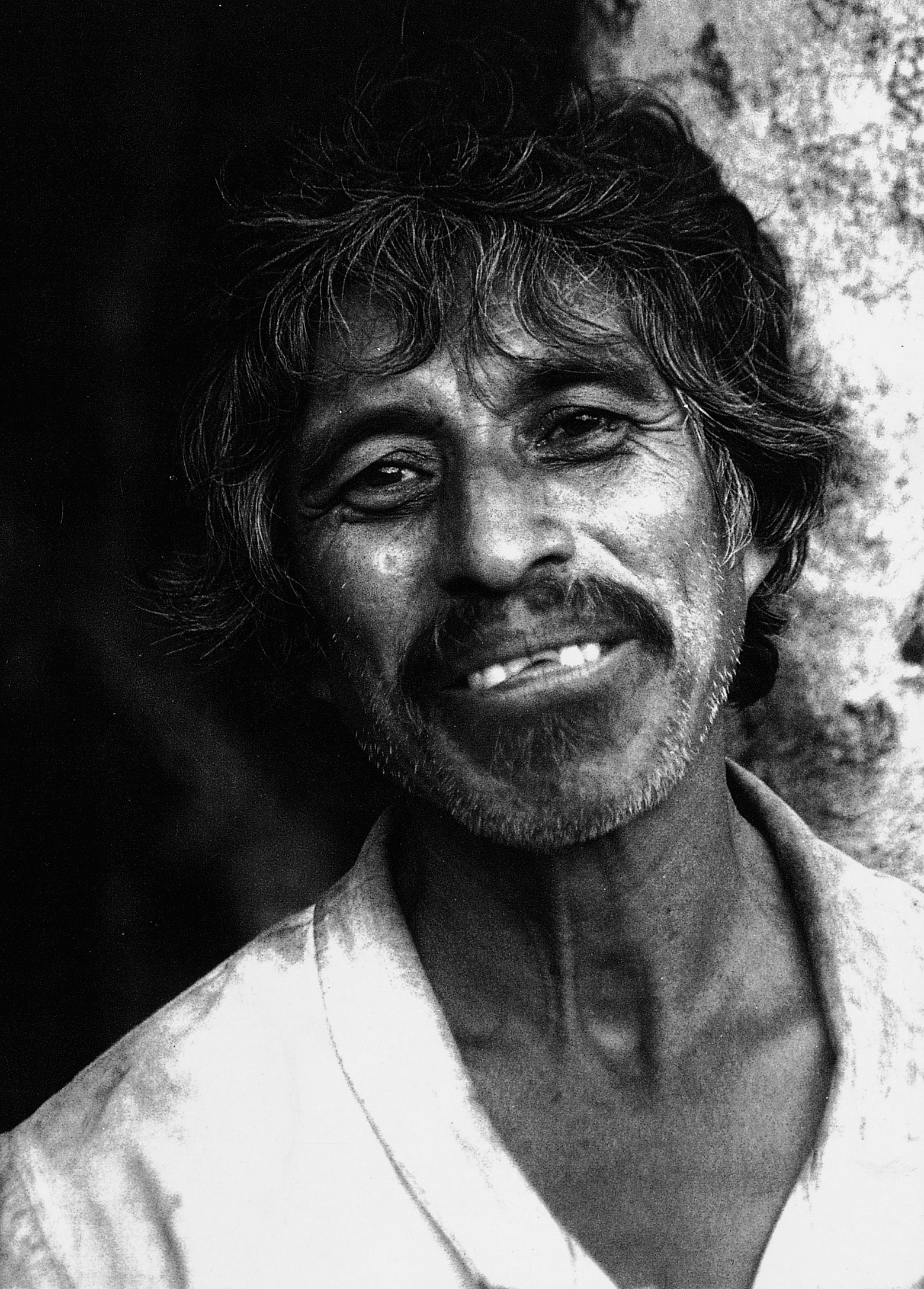

Ricardo

Ricardo Hernández made twelve cents an hour picking coffee beans on slippery, dangerous trails in the mountains above Matagalpa, Nicaragua. Each bag that he hauled a half mile down to the collection point must have weighed one hundred pounds. It was the only job he could get to provide for his wife and four children. When I told him that, in my country, a cup of coffee could cost three dollars, he nearly fell over.

Everything about Ricardo’s appearance spoke of a man pushed to his limits by poverty and the grind of daily labor: His clothing was stained with sweat and dirt, and his leather sandals were ripped. His eyelids sagged, his lips trembled, and his shoulders slouched. The tendons of his throat were as tight as piano strings.

He stood, looking forlorn, among seventy other workers waiting in the stifling heat to collect their weekly wages. He fidgeted. Eventually the foreman called his name. Ricardo, hand outstretched, moved quickly to take the money. Then, stepping under the shade of the trees, he counted the seven bills again and again. Finally he thrust them in the pocket of his pants and walked slowly down the dirt track with his head bent.

Two days later I followed the same track several miles to Ricardo’s house, a small adobe structure with a tin roof. Ricardo was sitting in the dirt rubbing a salve made of honey and herbs on his swollen ankles. Two of his children played with a rusty powdered-milk can on the porch. After visiting with him for a while, I asked if I might take his picture; I would give him money, I said. He nodded yes.

When I looked at him through the camera lens, his facial features seemed to be a composite of many nationalities. He could have been born in Turkey or Bolivia or India.

I knew he would rise again the next day and go to the mountains to gather coffee beans for wages that barely kept him and his family alive.

Heleni

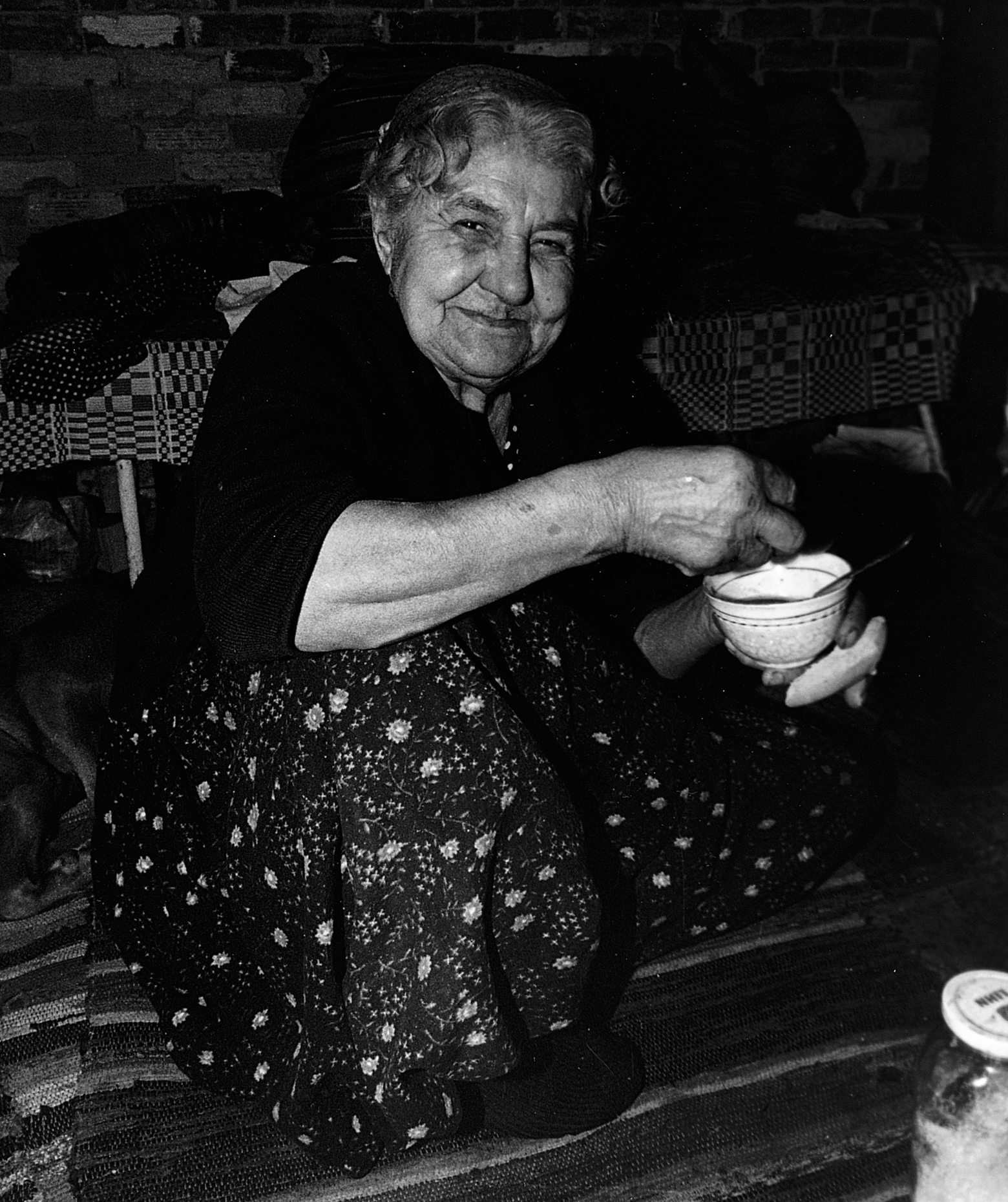

I lived for a month in Lesvos, a mountainous Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea, where I slept in a garret room in the house of an elderly widow named Heleni. In exchange for lodging, I hauled wood, carried water from the town well, and tended her small flock of goats.

Heleni was barely five feet tall and badly stooped from age. When she swept out her rooms, her head nearly touched her knees. But she went about her day laughing and smiling and talking to herself, her baggy, old-fashioned pantaloons giving her a clownish air.

As fall passed into winter, my room in the garret grew frigid, and I could see my breath even in the middle of the day. When the snows came around the beginning of December, Heleni, her dog Muesel, and I began to spend much of our time around a sheet-metal stove in the living room, our stocking feet stretched out against a low table. Portraits of her Greek and Turkish parents and deceased husband looked down at us from the wall. We ate sumptuous lamb stews and casseroles of cabbages and carrots in olive oil, all of it soaked up with fresh bread. We savored pastries and drank strong coffee from small white porcelain cups. The winter wind rattled the windows and shook the roof, but we were warm, spread out on big yellow pillows with Muesel curled up between us.

Heleni’s birthday was December 22, and I made plans to surprise her. That morning I watched from the garret window as she brought in the morning wood. At just the right moment I lowered a gift basket to her: a bouquet of flowers, chocolates, and two pairs of red winter socks. As the basket reached her, she danced a brief reel in excitement and then stopped to blow me kisses.

Willie

One winter I lived in Cumbria, England, where I met Willie Bentham, a sheepman who lived in a stone house in Dent village. We would often eat together at Sun Pub in the evenings and play dominoes beside the open fireplace.

On Christmas Eve the pub was packed. Willie sat in a straight-back chair with his walking stick between his knees, wearing his best shirt and coat and new boots. He and I made a few attempts at talking over the din, then gave up and simply sat together looking at the throngs of drinkers. After a while we slipped out the back door into the night.

Outside it was calm and clear and cold. The snow had stopped falling, and the full moon shone on the crow’s-feet around Willie’s eyes and the faint smile on his lips. “Come,” he said, “we’ll go down t’river and see if badger has come for a drink.”

Once we got there we scanned the shoreline for a sign of the animal. The branches of the bare trees cast thin shadows across the ground. “Aye, look here,” Willie whispered, gently grabbing my arm. “Our friend badger has been here again — see the tracks? Coming to have a drink, he was.”

Willie took a deep breath and looked back at the village. The streetlights cast a glow in the sky above it, and we could hear cars on the roads. “Some things have changed, and some have stayed the same,” he said. “I guess I’m not one for these noisy times.”

Alphens

On tiny Union Island in the Caribbean, I came upon seventy-year-old Alphens Ryan breaking stones with a hammer in the stifling heat. He explained that the road crews paid for crushed stone. “Do you like this work?” I asked. He replied, “Oh, yes, this is very good. I am happy every day to do this job.”

At Mr. Ryan’s invitation, I went to visit him that evening in his one-room shack on Good-for-Nothing Hill. He seemed happy I had come and apologized for his bare feet and sweat-stained shirt. I dug two cold beers out of my backpack, but he refused the offer. As a church man, he said, he did not partake of hard spirits.

In the shack were a cot, a chair, and a rickety table; some shirts and a suit hung from a nail. I sat on a wooden banana crate and listened as Mr. Ryan spoke happily about the island, its history, and the people of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

“Mr. Ryan, you live so simply,” I said. “You don’t even have a mirror on the wall.”

“I never did court vanity,” he replied, sitting up in his chair a bit straighter.

On Sunday Mr. Ryan escorted me to Mount Zion Baptist Church, a large tent with a small but enthusiastic congregation. He and I sat next to each other on folding chairs while the preacher implored everyone to repent of their sins. The service included dancing and shouting and the shaking of rattles and tambourines.

I returned to Mount Zion Church another day when Mr. Ryan was performing a baptism for twin three-year-old girls in matching bright pink dresses. The ceremony was not much different from those I had witnessed in New England. On the way home Mr. Ryan told me that when he’d first become a baptizer in the holy faith, he’d gone by the customs of the old African baptizers, whom his grandfather had known in the slave times: He’d build a wattle-and-daub hut in the woods and lock three or four teenagers in it for a whole week with only water and crackers. “This was for them to repent of their ways and pray for salvation,” he said. After the week had passed, he’d take them down to the sea and give them a complete dunking, as they’d done in the river Jordan in the Holy Land. “And I tell you,” he said, “that week in the hut prepared them to meet the true heart of Jesus the Christ. Amen.”

Brenda and Esperanza

When I asked her with whom she wanted to be photographed, young Brenda Montoya Aleman replied, “My great-grandmother.” She disappeared into the dark interior of her adobe house and reemerged with Esperanza Montoya Venabides, ninety-five. In the pale afternoon light of a side street in Matagalpa, Nicaragua, Esperanza put her right arm around her great-granddaughter’s shoulder, and they posed beneath a red hand-painted word on the door to their home: “Vota” — Vote.

While I took their picture, Brenda told me that her great-grandmother had been an insurgent with the Sandinista National Liberation Front. After the Sandinistas had overthrown a forty-year-old dictatorship, a bloody war had raged between Daniel Ortega’s leftist Sandinista government forces and the right-wing Contra rebels, who’d been armed by the United States.

The aroma of food cooking over a wood fire wafted through the open door, and Brenda motioned for me to enter. Inside, over a meal of rice, beans, and tortillas, I learned that Esperanza had lost both her son and her husband to the war against the Contras, as well as cousins, nephews, and nieces. Though she had not carried a gun (she’d been seventy-seven at the time the war had started), she’d cooked for all the Sandinistas who’d passed by her home and had often given them a place to sleep.

Brenda translated her great-grandmother’s slow, careful speech as Esperanza told me how, during the long war years, she’d made tortillas from four in the morning until midnight every day to feed the fighters. “Corn is the strength that we subsist on,” she said. “A person cannot work, cannot think, cannot exist without our corn.” Though they hadn’t won, she said, they hadn’t lost either. “Our lives in Central America,” she said, “are like tender new shoots of corn that always need tending and protecting.”

“What They Taught Me” is excerpted from Grandfather’s Gift: A Journey to the Heart of the World, by Ethan Hubbard. © 2007 by Ethan Hubbard. It appears here by permission of Heron Dance Press (www.herondance.org).

— Ed.