The beauty of Barry Lopez’s writing is in the details. On the first page of Arctic Dreams (Vintage), he writes about walking among birds in the high Arctic who, in the absence of trees, nest on the ground: “I gazed down at a single horned lark no bigger than my fist. She stared back resolute as iron.” His response is to bow to these birds, a gesture of prayerful respect and humble appreciation.

Lopez’s first nonfiction book, 1978’s Of Wolves and Men (Scribner), examines humanity’s relationship to the wolf. The book helped reshape Americans’ attitudes toward this native predator and likely played a role in the reintroduction of the wolf in the Northwest. Since then Lopez has produced more than a dozen finely crafted books. In “A Voice,” the introductory essay of his 1998 collection About This Life: Journeys on the Threshold of Memory (Vintage), Lopez recalls having pushed his alphabet blocks out the window at the age of three so his mother would have to take him out to the garden to retrieve them. It’s a richly symbolic vignette — words propelling the author into nature — that foretells a life of conscious exploration. It’s no accident that About This Life has only thirteen pages of autobiography. The rest of the book is a selection of Lopez’s finest essays. The message is clear: “If you want to know me, read my work.”

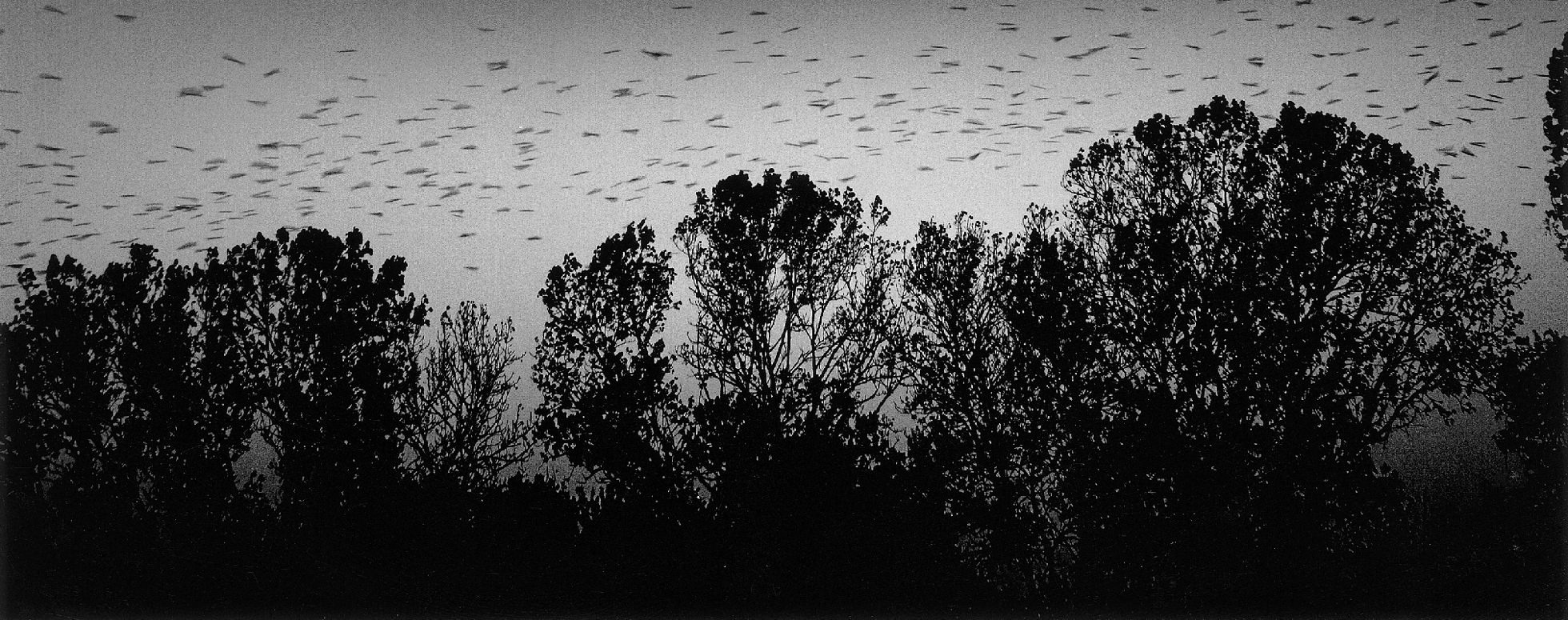

Lopez spent much of his boyhood in the wild creeks and vast fields of the mid-twentieth-century San Fernando Valley. For his tenth birthday a family friend gave him a flock of twenty homing pigeons. Watching the birds soar and dive was “a source of indescribable joy,” Lopez writes in the essay “A Voice.” “I would turn slowly under them in circles of glee.” When he was eleven, his family moved to New York City, and he studied at a Jesuit prep school in Manhattan. Though he missed, to the point of grief, the coyotes, snakes, and other creatures of the valley, he relished the academic challenges of his new urban environment. He devoured novels by John Steinbeck, Herman Melville, and others and went on to college at Notre Dame. As a young man Lopez considered becoming a Trappist monk and spent time at Gethsemani, the monastery where the author Thomas Merton lived. Though Lopez ultimately didn’t choose the monastery, he views his writing as morally informed and sees parallels between the monastic life and the writer’s life.

Lopez settled on the west slope of the Cascade Range along the McKenzie River, east of Eugene, Oregon, in 1970. He continued to maintain this home alone after a thirty-year marriage ended in the midnineties. He has long been committed to a domestic partner and her four grown children who live nearby. His home is decorated with friends’ artwork, and the dining table where we conducted this interview is made of black walnut cut and milled by Lopez and a friend.

The evening before our meeting, Lopez asked if I could pick up a sign he’d requested from the Eugene office of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. An unusual number of salmon were spawning in the McKenzie River just across from Lopez’s home, and he wanted to warn boaters not to disturb them. We met on a bracingly fresh morning on the autumnal equinox. Lopez poured me a steaming mug of herbal tea, and we sat down to talk. More than three hours later, we clicked off the tape recorder and walked down to the river. A couple of hefty chinook salmon wriggled in the clear water, sending out tiny waves in all directions.

BARRY LOPEZ

Shapiro: What are you working on now?

Lopez: Usually I’m uncomfortable talking about works in progress, but I can tell you what I’m doing besides writing. Lately I feel a sense of urgency, a sense of national threat, and because of that, I’ve become more involved with higher education, with public presentations and collaborative work, and with trying to advance the work of younger writers. For someone who’s not a social activist, I seem suddenly to be up to my neck in such things.

Shapiro: Political things?

Lopez: Yes. I really think the direction the country is headed is self-destructive: the psychological relief we pursue with consumption, the compulsion we have for distraction, the degree to which lying is now acceptable in business and politics.

Maybe what I’m really working on is grappling with my own reputation as a writer and what to do with it. In a very small way I’ve become something of a public figure. If you find yourself in this position, what are you supposed to do? The answer, for me, is to take it for what it’s worth: Lend your name to worthy causes and help younger writers. Read other people’s manuscripts. Try to open doors for writers who are devoted to story and language, and who have serious questions about the fate of humanity.

The main focus of my written work now is a large nonfiction project, on the scale of Arctic Dreams. It’s set in five different places I’ve been traveling to: the high Arctic, the Galápagos Islands, northern Kenya, the Tanami Desert in Australia, and Antarctica. It further develops the theme of Arctic Dreams, which is a relationship between landscape and imagination.

I’ve also recently published a set of interrelated short stories called Resistance (Knopf). In it, a fictional Office of Inland Security sends a letter to several American writers and artists, informing them that the American public finds their work disturbing and regards their politics as a threat to democracy. It’s a letter of indictment and notification. The government wants to have a talk with each of them. It’s not the kind of letter we’re used to seeing in the United States, but throughout history dictators and tyrants have behaved like this. There are nine testimonies in Resistance from people who refuse to cooperate.

Shapiro: When I heard you speak in 2001, you mentioned that you’d had meetings with an oil-company president.

Lopez: Yes, the president of Arco called me and said he’d been reading my work for ten years and really wanted to talk to me about civilization and oil and, as he put it, “where the hell we’re going.” I thought this was a strange request, but we’re living in strange times, so I said yes. We flew up to the North Slope of Alaska and walked around for a couple of days. This man was really serious and deeply concerned. He was looking for solutions.

Through him, I began to meet a number of executives who were profoundly embarrassed by the Enron fiasco, and by the arrogance with which the tobacco industry had testified before Congress, and by a certain kind of ruthlessness in American corporate culture. Being businesspeople, however, such men and women have very few outlets for frankly expressing their concerns. They can’t speak about them at a stockholders’ meeting; they can’t address these issues at a board of directors’ meeting; they can’t even speak openly among other executives without drawing suspicion. I want to get these savvy, ethical, powerful businesspeople together to talk. Often they don’t even know of one another. They’ve been politically isolated by our polarizing society.

Shapiro: And by laws that require them to try to earn the greatest profit for shareholders. These people are legally prevented from acting first in an ethical and moral way.

Lopez: They are. So I’ve been trying to create venues where they can talk to each other. I’m interested in how the citizenry can address issues such as the availability of fresh water without involving government and business. Businesses are interested in solving problems to their advantage. Nothing against them — that’s what they do. And government is interested in solving domestic problems in a way that helps the economy, which may not be what citizens want.

Part of what has happened to me recently is that, like so many others, I’ve become acutely aware of the political danger the country is in. The champions of material wealth, the acolytes of technology, and the religious extremists are so loud, so bellicose, so uncompromising. Who will rein them in? Who’s not afraid to criticize their notions of “progress”? The hallmark of their progress now in Third World countries is not further stratification into the haves and have-nots; it’s social disintegration. The social cohesion that defines a village; that provides healthcare, insurance, love — everything that’s been turned into a product or an industry in our culture — is threatened by the indifference of corporate capitalism.

As a writer, I have a responsibility, as I see it, to society. I want to be careful, however, not to take up a position of thinking that I actually know something, that I have answers. The only thing I know as a writer is how to tell a story. I sit at the typewriter and make a pattern, a story about how my culture works or behaves. Do you know that essay “Flight”?

Shapiro: Yes, in About This Life.

Lopez: I had this question: Why are air freighters flying all over the planet every day with all these products? What’s behind this? “Flight” is a piece of journalism, a reporter experiencing a set of events and then writing about them in such a way that you can grasp something as abstract as high-speed consumption. I don’t have any particular skill with economic data.

Shapiro: But the reader probably would not be drawn in by the economics. I was interested in that essay because it’s personal: you’re on the phone with your wife saying, “I’m just so disoriented,” and she says, “That’s because you’re not going anywhere; you’re just going.” That human story is compelling.

Lopez: I feel the same way. I think the writer should serve that function in society. The writer should be a person who sojourns in that chaos and comes back to write something cogent and coherent. That’s one’s service to society, and that’s the relationship I want with the reader. I want to say, “This is what I saw — what do you think?”

Shapiro: Most of your nonfiction involves travel to remote places.

Lopez: I think my compulsion to leave town is based on a belief that it is only by leaving the security of the familiar that I can learn whether my particular metaphors can continue to ground the reader in something trustworthy. If I put myself, say, at a social and cultural disadvantage in an Eskimo village, where nobody wants to talk to me, and I go through all of that self-doubt about whether or not I should be there, totally confused — if I have those thoughts, I think, Good, I’m in the right place. Now I just have to hold on in that windstorm.

When I come back from these places and tell readers something utterly remarkable about those people, the last thing I want them to think is: I want to go live in that village. You can posit that many traditional societies have basically solved the problems of maintaining stable social organization: holding a family together around sexual infidelity, spiritual infidelity, economic infidelity. But they can’t solve our problems for us. We have to fend for ourselves to straighten out the social chaos we’ve created; our families have been torn apart by the pressure of consumption and having to get and keep jobs.

Here’s something disturbing: We can’t survive economically in this country without a high rate of divorce. Social disintegration is required for the economy to work. The family has got to be broken down into independent consumer units. In divorced families, kids often have two homes, two sets of clothes, two sets of toys, two of this, two of that. Unless you undermine stable extended families, unless you regularly change the “answer” to filling a wide range of individual human needs and constantly subdivide those needs, you can’t keep the American consumer juggernaut going.

So if I go to Australia and visit with Warlpiri people, what can I learn from them about long-term social stability? They don’t have the latest cars or clothes, or this pervasive, hyperkinetic milieu of distraction in which we live. But they have to deal with the same basic social problems. And perhaps we can learn from them.

My writerly responsibility is to try to be discerning — even when camped in the Transantarctic Mountains — about how these circumstances I’ve put myself in relate to readers who are just trying to hold a family together, stay employed, deal with dying parents, and change the baby’s diapers when they haven’t slept in twenty-four hours. How can I help? The one thing I know how to do, I think, is turn a pattern I see into language. I like to go a long ways away, try to recognize a human pattern there, and then put it in an accessible form for people at home, so they might recognize the outline of what’s been troubling them and figure out what to do about it.

I’ve become acutely aware of the political danger the country is in. The champions of material wealth, the acolytes of technology, and the religious extremists are so loud, so bellicose, so uncompromising. Who will rein them in? Who’s not afraid to criticize their notions of “progress”?

Shapiro: I remember as a child reading Loren Eiseley. He wrote about fields being plowed over for shopping malls and wondered what would happen to the rabbits and the mice and the other creatures who’d made that piece of land their home. And I thought, Finally, somebody feels the same way I do. I think that’s one of the greatest services a writer can provide, to say, “You’re not alone in these feelings.”

Lopez: One of the things you have to do when you edit your work is make sure that when you use the first person, it’s about more than just you. We need the story of us. If I feel compelled to share something about my private life, I say to myself, This had better be good. When I put About This Life together, I decided, for the first time, that I’d include something about my private life, hoping my experiences would be easy for people to identify with.

Before that, when I wrote Arctic Dreams, the image I had of the reader was always of somebody standing right next to me. I was pointing something out and talking about it. But what I really wanted to have happen was for the reader to forget about me, to step in front of me and think, Oh my God, I’m sitting here watching this polar bear.

What’s changed recently is that I’ve become more revealing and autobiographical in my nonfiction. In this new book, I have a very different kind of narrator coming along.

Shapiro: My one frustration with your work is that sometimes I want you to be more outraged, more judgmental. You’ll describe something — for example, the roar of the caged lion in a cargo plane — and let the reader feel what you’re feeling, but you won’t try to be the judge. But sometimes I just want to say, “Damn it, Lopez, get ticked off!”

Lopez: The first time I let my sense of outrage show was in an essay called “The Rediscovery of North America,” which came out as a book in 1991. We live at a distressing time in American history, and, yes, I am outraged. Inevitably those feelings will generate a story, at the heart of which may be a renunciation of some negative aspect of our culture. The most obvious example of this would be Resistance, in which I make clear my sense of alarm about how far this government has gone in stifling civil liberties in order to advance its social and economic agendas. But it’s not I, the author, speaking in Resistance. The individual narrators of the stories determine the language and the point of view. Otherwise it wouldn’t be fiction.

Sometimes people ask how I decide, when I sit down at the typewriter with a particular thought or emotion, whether I’m going to write fiction or nonfiction. To me that’s like asking how you decide whether you will paint or dance. They’re two different things. The decision is almost unconscious. It’s a sixth sense about how to get at the truth of existence. Truth in a piece of nonfiction lies with material that can be verified outside the author’s authority. You can’t take that route with a short story. Its truth is an emotional truth: is the pattern of events in this short story true to what I know about what it means to be human?

Shapiro: In About This Life, you wrote some about your own childhood. When you were three, your family moved from suburban New York to greater Los Angeles. Parts of LA were more rural then.

Lopez: I wrote a piece for LA Weekly called “A Scary Abundance of Water.” It’s partly about the geography and the history of water in the San Fernando Valley, and partly about trauma in my childhood. Back then, to the northwest, toward Chatsworth, LA was open fields and braceros [laborers]. To the southeast, toward Van Nuys, was where all the development was taking place, and apartment buildings were going up. And I was living right on the crest of this wave of development that was wiping out the agriculture. My emotional growth took place on the border between those two very different communities. Agriculture in the San Fernando Valley went out like the victim of a flash flood. If I remember correctly, in 1950 Los Angeles County was the most productive agricultural county in the United States. By 1960 agriculture there was vestigial — it was nearly gone. In that microcosm you can see the pattern of what has happened to rural land across the United States.

Shapiro: When you were eleven, you moved back to New York. From what you’ve written, it sounds as if you lost your foundation, your connection to the world.

Lopez: A lot was going on for me. Here’s this eleven-year-old kid running around in the Mojave Desert, and then a few months later he’s studying Latin in a Jesuit prep school in New York City. Twenty years after that, you see a writer traveling in the Arctic with Eskimos, and a few months later studying anthropology journals in a library in Oregon. So the same pattern is there.

What I loved about the city were the museums and the theater. I did feel a loss — the landscape of my childhood was missing — but what I found was something equally fascinating. It was simply a more intellectual, more aesthetic realm of experience. That dual exposure predisposed me not to trust either one completely.

Shapiro: You almost became a Trappist monk. Why didn’t you choose that path?

Lopez: I tried twice: once when I was a senior in high school and once after I graduated from college. I don’t know that there was any clear reason why I turned away. After college I was at Gethsemani, the monastery where Thomas Merton was. Monasticism was a calling, but it wasn’t loud enough for me to heed it. I see some parallels between the kind of life I lead now and that life. What attracted me to Gethsemani was the combination of physical labor and prayer. In some sense, I have that here, cutting firewood for heat and then sitting down to write. I remember saying to an interviewer in 1985 that writing is my prayer. It’s a moral act for me.

There’s a certain deep longing in prayer for reunification with the divine, and there’s a strong leaning toward that in some of my work. I’m thinking about a piece of historical fiction called “The Letters of Heaven” [published in Light Action in the Caribbean (Vintage)], in which two sixteenth-century saints become lovers. Five hundred years later, their love letters are discovered. Two people whose lives were devoted to God became involved with each other in a way that the Church condemned. Yet, for them, this was the way they lived out their faith. Their testimony, their behavior toward each other, was all about a deeper pursuit of a relationship with the divine.

Shapiro: Your work is clearly propelled by curiosity. What are you most curious about?

Lopez: I’m curious about my immediate surroundings. I want to know why there are more salmon in the McKenzie River this year than there have been for the past twenty-some years. All of a sudden there is this big run of spring chinook, so I’m curious about that. I’m also curious about an osprey nest on the other side of the river that was knocked down in a storm five years ago, but now a breeding pair seem interested in rebuilding there. I’m curious how long that’s going to take.

When I travel, I’m curious about everything. While working on Arctic Dreams, I let the research go on for about two years before I developed an outline for the book, because I knew that developing an outline would narrow the field of my curiosity. So I let my curiosity flow until I thought, OK, I’m drowning. I need an outline here. I need a boat.

That kind of curiosity is not unique to writers. What may be unusual is that writers tend to push that curiosity farther. I have no sense of reserve when it comes to wanting to know something. I remember when I was a kid in New York, a friend and I were walking past an exotic automobile, an Aston Martin or a Ferrari, double-parked on Park Avenue. I immediately left the sidewalk, walked around the vehicle, and looked in the windows. My friend said, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m looking at the car.” He said, “You shouldn’t do that; people just don’t do that.” I said, “Maybe they don’t, but I do.”

Another New York friend said to me a few years ago, “It’s so clear you’re not from the city. You’re always looking up.” He said people in New York don’t look up. I look up at the buildings. I look up at the sky. I’m curious about all of this. It’s a hunger. I have to feed it.

When I drive anywhere, I don’t keep the radio on or have a CD going. I always want to be watching out the window. I’ve driven this road along the McKenzie River thousands of times in thirty-six years, but there’s always something going on that I’ve never seen before, and I want to know what it is. When I sit out there on the deck every summer, reading, an insect I’ve never seen before always ambles across that table.

These are all cues to pay attention, to stay awake. I sometimes say the first rule of everything — including writing — is to pay attention. To do this you’ve got to be curious all the time. I admire a pilot’s ability to perform a repetitious preflight checklist. I couldn’t do that. My mind would wander: Is that bird going to stay there at the edge of the runway, or fly toward us? I have the ability to close everything else out, but not an unflagging discipline for rote work. That’s both a risk and a blessing when you’re doing research. You can suddenly be distracted by what seems extraneous to somebody else.

We not only believe that we’re separate from nature; we actually think we can direct it. We refer to components of the earth as “resources” rather than as entities, life systems unto themselves. For many people, the earth has no meaning until they find utility in it.

Shapiro: When you talk about how you approach a place, you say you listen. It’s not constant motion; it’s not even recording. . . .

Lopez: It’s being present. I remember this Nunamiut Eskimo man I mention in Of Wolves and Men, Justus Mekiana. I said to him, “When you go to a place you’ve never been, what do you do?” He said, “I listen.” That was his lesson for me: that’s what I should be doing — not talking, but listening.

Another dimension of my work now is public speaking. Public presentation is all about talking. If you’re not careful, you can begin to think that you’re somebody, and if that happens, it can easily harm your work. I don’t want to lose the habit of listening. I don’t want to close out the voices that tell me what I don’t know. The temptation is there, later in life, to think you know what’s going on, but you don’t, no more so than anybody else. That’s why the library is full of books.

Shapiro: What has drawn you to connect with indigenous and aboriginal people, and what have been the most important things that you’ve learned from them?

Lopez: I’ve gained an understanding of the responsibilities of the storyteller. I’ve learned to exist comfortably in the world of comparative ways of knowing, without trying to say that one is superior to another. I’ve learned to watch animals with less judgment and presupposition. I’ve learned about the importance of elders in a society and about why certain groups of people survive over thousands of years. By developing a sense of respect for indigenous people, I’ve learned how to develop a sense of respect for everything alive. I’ve learned that the world knows way more than I do.

People who say they are searching for an exotic experience often have already figured out what that exotic experience is going to be. “Exotic travel” for some people is just another version of a theme park. They don’t want any surprises.

Shapiro: That things are more complex than we ever thought.

Lopez: Absolutely. I’ve learned the shortcomings of my own education. I’ve been exposed to many Western ideas, and I love and respect that knowledge, but native people helped me understand it as one way of knowing. It’s internally consistent, it’s engaging, but it’s not the whole truth. No one can tell the whole truth.

Shapiro: We are a society in constant motion. People move all the time. I wonder what you’ve gained by choosing a place and committing to it.

Lopez: I’m comfortable here, and the things I think I need to know, I get from here. A habit of permanent location in a time of dislocation is also an opportunity to learn about something we’re abandoning. I’m concerned about the rootlessness of so much activity in American culture. My allegiance to this place offers me something I can’t explain, which one day I may or may not write about.

Most everything in my home was made by friends. When you talk about being tied to a place, I look around at these gifts and feel a sense of community. I’ve grouped the books of several friends in each room, so when I walk in there’s all of David Quammen’s work, or Wendell Berry’s work, or Annie Proulx’s work. When I go through periods of self-doubt, feeling my work is no good, I’m borne out of that preoccupation with myself by looking at all this other work.

Shapiro: Indigenous peoples are so involved with nature, whereas our society typically views itself as separate from nature. It’s something we go and see, not something we’re a part of.

Lopez: I think this preconception is going to prove economically and politically disastrous. “Unenlightened” hardly covers it. The central distinction between indigenous people and us is that they continue to participate in the drama of life. We have attempted to step out of that drama. We not only believe that we’re separate from nature; we actually think we can direct it. We refer to components of the earth as “resources” rather than as entities, life systems unto themselves. For many people, the earth has no meaning until they find utility in it. Coal is without meaning unless it’s used to fire a machine. A gazelle is without meaning unless it’s eaten.

What we’re going to find out in the next hundred or so years is whether consciousness is maladaptive. I would guess it could prove so, meaning the human organism won’t survive. The notion that if we fail, then life in general will fail, however, is a non sequitur. Signs in hotel bathrooms urge us to help save Mother Earth by reusing the towels. We can do things that will help us survive as a species, but Mother Earth is going to be here long after we’re gone.

Shapiro: But we’ve harnessed such overwhelming power: nuclear weapons, for example. We can take ourselves down stunningly quickly and also cause suffering and extinction among our fellow species.

Lopez: We can. We compare with that meteor that smashed into the Yucatán Peninsula 65 million years ago, triggering the Cretaceous extinction. There’s no denying that. But there are some choices people can make that would ensure a better life for their children and grandchildren. All it would cost them is a few comforts, which, at least in this country, most people don’t seem inclined to give up.

Shapiro: It seems some people not only don’t care about despoiling nature; they actively, and almost angrily, conquer and damage it.

Lopez: I think that tendency is an expression of fear, a fear of not having enough control. Modern culture makes each of us so anxious about being able to control our own fate that any opportunity to control the environment around us becomes inordinately attractive. People pursue money because they believe in a myth that says, “With money you can control your environment.” The more money you have, the more you believe you can control your fate. This is naive.

Shapiro: The Arctic has probably changed a great deal since you first visited there thirty years ago.

Lopez: Outside of the worldwide effects of global warming and the impact of chemical pollution, I think the most profound changes have taken place in the villages, with the rearrangement of the traditional social order and the growth of consumerism and its destructive compulsions. Part of the reason I was drawn to the Arctic is that at that time, in 1976, it was a relatively stable environment. That’s not the case anymore.

I don’t think of the Arctic as a place that’s changed as much as I think about how people’s awareness of it has changed. To my chagrin, after Arctic Dreams came out, a growing number of adventure-travel companies began offering trips into the Arctic. One guy told me he built his entire business around reaction to the book in Canada.

I once wrote a piece called “The Stone Horse” [published in Crossing Open Ground (Vintage)]. For the first time in my life I was deliberately vague concerning the location of the place I was writing about. Travel writers are now faced with ethical dilemmas over how clear to be about where they are. Part of the reason remote places are changing today is that so many people are showing up and making their presence known. Travel writers have to ask themselves: What am I promoting here, and what are my responsibilities? At this point in my life I have doubts about what good can be achieved by going to very remote places and creating an aura about them that compels people to go there. It troubles me to consider what I have participated in. I often think the world would be better off if we just left these remote places to the people and animals who live there.

Shapiro: Do you think there’s something to be said for the writer as ambassador? It’s not good for a thousand people to go, but maybe it would be good for you to go and bring back an understanding of these places.

Lopez: We can’t control what people do, and I am suspicious of the idea of the writer as somebody who gets to go someplace the rest of us don’t. On every journey you bring something to a place, and you take something away. As a culture we’re more interested in what’s there to be taken than we are aware of what we bring. You’ve got to bring more than money when you go to a foreign place. You have to bring a willingness not to make it over in your own terms; not to demand, for example, that people always speak English. The best way to travel is to make proposals, not impositions.

It’s interesting to me that people who say they are searching for an exotic experience often have already figured out what that exotic experience is going to be. “Exotic travel” for some people is just another version of a theme park. They don’t want any surprises.

I wrote a piece for the Georgia Review [Fall 2003] called “Southern Navigation,” about traveling to Antarctica on board a German cruise ship. I occasionally get invitations from adventure-travel companies, asking if I’d be interested in giving shipboard lectures, and I said yes to this one. I wrote, in part, about the strange world of the ship, with its five-star meals and creature comforts. On the other side of those lounge windows was a place where I myself had been in very bad straits: cold, struggling against tough weather. We were following the path of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s famously desperate effort to survive the sinking of the Endurance, his journey from Elephant Island to Stromness on South Georgia. I had experienced similar physical hardship on my own Antarctic travels, but now I was in an environment of minimal risk, where everything was looked after. It’s hard to get a deep appreciation of what Shackleton went through over the course of several months on Elephant Island and South Georgia when you’re observing it all in ten days from the comfort and safety of a cruise ship.

Shapiro: You once wrote an essay about removing dead animals from the road. When I see these animals, I too want to get them off the road and give them back some dignity. Then I think, I can’t stop; it’s unsanitary and unsafe. But when I’m on my bicycle, not insulated by glass and steel, I sometimes will stop and move these poor creatures to the side. What enables you to break through that lack of connection that we have when we’re speeding along from one point to another?

Lopez: Stopping for the dead is a discipline of awareness. By setting up certain regular practices, we can ensure that we do not lose touch with life. If I want to write about the connection between culture and place, I’ve got to attend to those attachments. My taking an animal off the road or calling the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife yesterday to get that sign for the salmon — it’s all part of the same thing.

In an essay called “The Naturalist” [published in Vintage Lopez (Vintage)] one of the questions I wanted to answer was: What is a naturalist? What does it mean to be a naturalist today? Part of what it means to me is staying connected, keeping your hand on the real, living earth. Otherwise what you have to say is not going to be grounded in anything but abstraction. Ultimately a culture like that becomes completely solipsistic — its references are all to itself. I want to be in the woods every day, because every day there I’ll see something I’ve never seen before, and that’s a reminder that there’s no way I’m ever going to know everything.

I want to confront my own ignorance every day. Getting out of the car to get an animal off the road is a way to stay present to what’s going on around me. When you’re a visitor in traditional societies, it’s virtually never the case that you can tell a group of hunters something they don’t already know. They will listen to what you have to say, though, not to be polite, but because their minds are always open to the idea that you could have seen something that nobody had ever seen before. That openness to the numinous dimension of landscape is something to cultivate.

Shapiro: In “A Voice,” the first essay in About This Life, you meet a man whose teenage daughter wants to become a writer. You give him three pieces of advice.

Lopez: Yes, I advised him to tell his daughter to read widely, and I warned him to be aware that he could undermine her desire to read by making value judgments about what she’s reading. “Let her make the choices,” I said. Second, I told him he should help his daughter understand that someone could teach her to write, but to have something to say, to make a contribution to the community as a writer, she had to become somebody; she had to speak to us from a position that she is clear about. So, I said, “it’s more important for your daughter to become somebody than to learn the techniques of writing, if she wants to become a writer.” The last piece of advice was to help her get out of town, to get away from the familiar.

Shapiro: Have you made sacrifices to pursue this work?

Lopez: Choosing the life I did, I’ve lost some things that from time to time cause me deep anguish. Foremost among these are my social relations with other people. The truth is, if you’re devoted to your work, your family is going to pay a price. How you cope with that — opting for the work, or opting to maintain the long-term stability of a relationship — is a singular measure of character.

I’ve lived in this house for almost thirty-six years, but I know relatively few people around here. I’m not involved in the fabric of day-to-day life on the McKenzie, in part because my work is not local. My work is not here in the woods. If it were, I’d be logging every day with people whose lives I shared and with whom I went to church. I don’t have that. I’ve decided to do work that takes me a long ways away, and when I come home, what I really crave is privacy.

I’ve chosen a career that at times has made me very lonely. I can’t look at this as having made a sacrifice, though. When you choose one thing, you don’t get another. I love my work. It’s the good I have to offer. I don’t regret what I’ve done, but I have wondered what it would have been like if I had chosen the monastery, or a conventional family life. But those were choices I did not make.

Shapiro: Is there one quotation in literature that has been a guidepost for you?

Lopez: There’s nothing I would use to summarize my beliefs, but in Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick there’s a line about breaking through the “pasteboard mask” that has come back to me repeatedly. In some ways I see my life as an effort to break through a pasteboard mask, to destroy an illusion, to get at an important reality, because it’s the reality, not the illusion, that is to be trusted. The thing I am most fearful of in my culture is self-delusion: the self-delusion that deifies progress, the self-delusion that supports the superiority of one culture over another, the self-delusion of righteousness. The pasteboard mask obscures deeper meaning. It leads you to believe that deeper meaning doesn’t make any difference. That’s why I pull the truck over and get out and get the dead animal off the road: to keep pushing through, to make sure I don’t get trapped. It’s important to say that I don’t stop for every animal — there’s something in a particular animal that calls to me, and I pull over. Sometimes it’s so strong that I’ll drive two or three miles down the road and be unable to shake it off. I’ll have to turn around and go back and take care of it.

Our culture cultivates insensitivity and indifference. You’re in a little box, eating the popcorn consumer culture throws at you. You have one piece of tasty popcorn, and you want another. It’s easy to become remote and detached. Advertising tells us it’s OK not to love: “Don’t worry about other people,” it says. “Take care of yourself — and here’s a little secret: other people are too complicated for you to waste your time on. So just have this beer, this car, this vacation, and then the world will be under your control. You’ll get the things you need to get you where you’re going.”

I go back to Moby-Dick. That novel begins, “Call me Ishmael.” That means: “We’re going to be on a first-name basis. I am going to be your companion. You’re going to be in this with me. I want your trust. I’ll try to earn it. We’ll look at this thing together.” Never in that novel are you held prisoner by the limits of Melville’s imagination. The best kind of writing opens up a place sufficient to the reader’s imagination. I want to be the reader’s companion instead of the reader’s authority, and implicit in that is the knowledge that there are many readers far more imaginative than I am. I want to make a place where they can fully exercise their imagination. Not to do that is to cooperate in the building of this pasteboard world.

Shapiro: You’ve referred to your body of work as a “literature of hope.” Do you feel hopeful, and how do you distinguish between hope and optimism?

Lopez: I’m not optimistic. Optimism for me is about examining the evidence on the table, and the evidence on the table is bad. The way we are conducting ourselves in a world with limited supplies of fresh water is bad. No federal initiatives to address global warming; heavy-metals pollution; corporate avarice? Bad. The degree to which we are dependent on prescription drugs as a culture? Bad. So: optimistic, no.

Hopeful, yes. The reason is the staggering power of the human imagination to circumvent every kind of roadblock. So when I say a “literature of hope,” I mean a literature that gives readers the opportunity to be hopeful about their own circumstances and the circumstances of their communities. And if we encourage this sense of hope, people will exercise their imaginations in ways we could not have foreseen, and that will be our blessing and our release from pessimism. Somebody will see a different way to do things. I have to believe that my imagining a story will somehow help people to imagine a way around difficulty. Stories, in some way, are blueprints for the imagination. And I believe in the power of the human imagination to triumph over all these issues. For two-hundred-plus years the United States has failed to realize the dream of a Jeffersonian republic. We fail again and again and again, but we are still at it.

This is an abridged and edited version of an interview that previously appeared in the Michigan Quarterly Review.

— Ed.