For a long time the Dutch American ethologist and zoologist Frans de Waal was told by senior scientists that studying emotions in animals was off-limits. But while working with chimpanzees and other primates in the Netherlands in the 1970s, he observed behaviors that seemed to match human expressions of emotions — and why not? Chimps are our closest animal relatives. In the last twenty-five years many scientists have caught up with de Waal’s observations, and the notion that animals have emotions is no longer so controversial. Over the course of his long career he has conducted studies showing that our fellow mammals exhibit jealousy, grief, forgiveness, and more. He believes there “are no uniquely human emotions.”

His latest book, Mama’s Last Hug, takes its title from an emotional display de Waal witnessed between Mama, the matriarch of the chimpanzee colony at the Royal Burgers’ Zoo in the Netherlands, and de Waal’s biologist mentor Jan van Hooff, the cofounder of the colony. For decades Mama had been the loved and respected “alpha female” of her primate community, brokering reconciliations, soothing hurt feelings, and building coalitions. Before she died in April 2016, just shy of her fifty-ninth birthday, van Hooff, then seventy-nine, paid her a final visit. In a tender embrace captured on camera, Mama stroked van Hooff’s white hair despite the arthritis in her hands. The trust and love between these two elderly hominids was palpable. After Mama died, the other chimps washed and groomed her body. “For me,” de Waal writes, “the question has never been whether animals have emotions, but how science could have overlooked them for so long.”

As he details in his book, de Waal had a close relationship with Mama, too. He was the one who’d named her in the 1970s, while studying primates at the Royal Burgers’ Zoo. He had said goodbye to her months earlier, before returning to his work at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta, where he is director of the Living Links Center.

De Waal earned his PhD in biology from the University of Utrecht before moving to the United States in the 1980s; published his first popular book, Chimpanzee Politics, in 1982; and has since become a world-renowned expert on the similarities and differences between human and other animal behavior. He has studied capuchin monkeys, elephants, the crow genus of birds, and other species — but most extensively our closest primate relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos. When we scratch our scalps while solving a problem, he says, or feel the hairs on the back of our necks stand up when frightened, or brush a loose hair from the shoulder of our spouse, we are exhibiting typical primate behavior.

De Waal is also the author of The Age of Empathy, The Bonobo and the Atheist, and Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? His articles have been published in Science, Nature, Scientific American, and professional journals specializing in animal behavior and cognition. In 2007 Time named him one of its hundred most influential people in the world. His TED Talks and lectures have been viewed and shared millions of times online, and he’s a frequent guest on radio and television programs.

Now seventy-one years old, Franciscus Bernardus Maria de Waal — “Frans” for short — lives in Smoke Rise, Georgia, with his wife, Catherine. I had arranged to interview him in person before the COVID-19 pandemic made travel inadvisable, but he agreed to meet via video chat instead. We quickly overcame the awkwardness of relating through a computer screen and had a wide-ranging discussion interrupted by a few Wi-Fi glitches. He speaks excellent English, although at times his accent and sentence structures reveal his Dutch roots. At one point, while we discussed our childhood pets, he moved his camera to show me one of his many tropical-fish tanks. “The big fish do sometimes eat the little fish, so you have to be careful which ones you mix together,” he said. It wasn’t the last time he would point out that the natural world contains plenty of danger, along with great beauty and complexity.

FRANS DE WAAL

Courtesy of Catherine Marin

Leviton: Darwin wrote that the difference in mind between humans and higher animals is “one of degree and not of kind.” What do you think he meant?

De Waal: I think Darwin meant that the way we think is not fundamentally different from the way other species think, and I’m completely in agreement with him, even though people have attacked him for it over the years and said this was one of the things he was wrong about. There are some elements to human thought processes that are special, but the whole structure of cognition — how it works, what we can comprehend, how we find solutions to problems — is not so different. Human cognition is a variety of animal cognition.

Leviton: Why do you think some people have such a hard time accepting that idea?

De Waal: It’s strange, especially at a time when neuroscience is showing us the similarities between the monkey brain and the human brain. For instance, there’s no part of a human brain that you don’t also find in a monkey brain. There are no synapses or transmitters that are different. Even the blood supply is the same. We do have bigger brains, it’s true, which is certainly important.

Let me tell you a funny story about that. Five or six years ago some scientists were saying maybe we shouldn’t look at the brain’s size; the number of neurons might be a better measure of the brain’s power. And we thought humans came out on top in terms of neurons, so that was fine with everybody — until we found that elephants actually have three times as many neurons as humans. Certain people scrambled for an explanation of that, and now we don’t hear as much about counting neurons anymore.

That’s typically the human attitude: we need to be on top, and some people don’t want to hear about any evidence that animals can do things we cannot do or have some abilities we don’t have. For example, bats use echolocation, determining position by sending out and receiving sound waves, which is extremely complex. Ask any engineer who designs radar systems for airplanes. But because we are, in our minds, far above bats in the hierarchy of species, they don’t impress us.

Chimpanzees are our closest genetic relatives, and when they show extraordinary ability, some researchers get upset. Ayumu is a chimpanzee who lives at the Primate Research Institute in Kyoto, Japan, and his memory puts human memory to shame. He can remember the location and order of numbers flashed on a screen better than most humans. And though humans become less accurate when the time they see the numbers is shortened to 210 milliseconds, it doesn’t bother Ayumu. When he competed against a British memory champion, who was known for his ability to memorize an entire stack of cards, Ayumu won the contest.

We always look for traits that mark humans as special. Language is such a strong marker of humanity that in the eighteenth century a French bishop was ready to baptize an ape if he could demonstrate speech. In the 1950s we tried to teach language to apes, and it turned out they weren’t so great at it — not even at the level of a three-year-old child. But the apes still did much more than we thought they would, so the findings were hotly debated.

Leviton: We know animals communicate. Why isn’t that considered language?

De Waal: Linguists originally defined language as “symbolic communication.” Then apes showed the ability to use two or three hundred symbols, so linguists switched the definition: now language was not just symbolic; it had to be syntactical, meaning it had to have identifiable rules and processes governing structure. Even though we have a few studies that show a limited amount of syntax in animal communication, that’s still the dividing line. But it’s interesting that linguists had to change their definition as a result of the achievements of animals.

Apes aren’t the only nonhuman creatures capable of using symbolic communication. Bees dance to communicate about things they cannot presently see. The duration of a dance indicates geographical information about food sources, for example.

Leviton: It seems to me we don’t look at an animal’s life the way we look at our own. It’s like we don’t want to admit that bats are every bit as good at being bats as we are at being human.

De Waal: Yes, it’s a very anthropocentric enterprise. People sometimes ask me about ape-language studies, which have never impressed me. They say, “Don’t you want to talk to your chimps?” Well, no. I personally don’t see what I would get out of that. I’m much more impressed by how they communicate with and relate to other chimps.

We did experiments in which chimpanzees could work together on an apparatus, and we found they had ways of recruiting each other that we did not understand. We’d see a chimp approach another, and then they would walk to the machine we’d set up and start working together as if they’d agreed to collaborate. We’ve never figured out how they communicated the plan.

All species have complex communication. Dolphins produce a signature whistle, a high-pitched sound with a modulation that is unique for each individual. Females keep the same melody for their whole lives, but the males adjust their melody over time, until all the calls within a male alliance sound alike. We haven’t yet discovered why.

Leviton: Tools were once an important marker of human superiority. How do animals compare to us in their use of tools?

De Waal: The first studies that dealt with animal cognition were about the use of tools by chimpanzees. These were done by German psychologist Wolfgang Köhler a century ago. He was very much hated by the behaviorists — led by the American psychologist B.F. Skinner — who believed all animal behavior was the result of associative learning [a process in which a behavior is followed by a positive or negative stimulus that reinforces or discourages the behavior in the future — Ed.]. I’ve been at meetings where the behaviorists could not even pronounce the name Köhler, because they would be so upset. Köhler, Köhler! [Laughs.] He was the first to say animals could think, based on his work with chimpanzees. He’d hang a banana very high and give chimps sticks and boxes. And he would not train them. Behaviorists train their test subjects by giving them little rewards for every move they make. Köhler wouldn’t do that. And, after a half hour or so, one of Köhler’s chimps would stack the boxes, climb up with a stick, and get the banana. He concluded that this chimp had had an insight — in German, Einsicht — and solved the problem in his or her head. This was the opposite of what animals were supposed to do. They were supposed to operate completely on trial and error.

Now we have “insight learning” studies on all kinds of species, not just apes. Edward Tolman, who studied rats and has a building named after him at the University of California, Berkeley, talked about rats’ “mental maps.” A rat doesn’t just learn to go right or left as a result of behavioral rewards, Tolman said; he develops a map in his head of the whole maze.

The reason Tolman ended up in Berkeley was because the East Coast establishment were strict Skinnerians [followers of B.F. Skinner]. It wasn’t until the 1990s that we finally started to win the battle with the behaviorists, and those who talked about animal cognition got a foothold and got funding for experiments. We don’t yet have a grand theory of cognition, but at least we have abandoned Skinner’s reductionist idea that it’s all mechanical, a result of reward and punishment.

Leviton: When I studied psychology in the 1960s, I remember it being very divided between behaviorists and those I thought of as humanists. The Skinnerians believed people, too, were like automatons. There was something almost fascistic about it.

De Waal: Skinner’s utopian novel Walden Two, written in 1948, is a rejection of free will and posits that cultures and people can be engineered to be a certain way. So, yes, behaviorism had that element, that emphasis on control. I was trained in Europe, where Skinner was not nearly as strong an influence. In the U.S. behaviorism was almost a religion. My book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? has a lot in it about these battles with behaviorists. People who read it now may wonder what all the fuss was about, but it was a big deal at the time.

How much we know now about animal cognition and animal emotions is uncomfortable for some people. It does mean we need to pay attention to how we treat animals.

Leviton: In philosophical and practical terms, what’s the difference between studying animals in laboratory conditions and in the wild?

De Waal: There used to be a tremendous amount of tension surrounding this. Initially we considered fieldwork nonscientific. Places like the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, which was established in 1930, were the standard. We worked with captive apes, and we did controlled experiments. When researchers went into the wild and saw glimpses of apes’ natural behavior, other scientists were not impressed. Then people like Jane Goodall went into the field in the early 1960s and stayed longer. They didn’t just see glimpses. They were living with the chimps. They watched their behavior develop over time, saw them raise their young, and started to recognize all the individuals in a community. Then fieldwork became more serious, and we began to respect it. The field-workers started to look down on work with captive apes and criticized the artificial environment the apes lived in as a kind of prison.

Now the field-workers are encountering difficulties because ape habitats are under threat or have disappeared. And they need labs, because they want to analyze feces and urine and blood samples. They want to examine the DNA of animals or their hormone levels. So we have lots of collaboration between laboratories and field-workers. We’ve found a balance.

Experiments with captive apes have also gotten much more advanced. We sometimes discover things field-workers don’t know about. For example, when I was a student, I found out chimpanzees sometimes reconciled after fights. It was only twenty or thirty years later that field-workers observed that process in the wild. So sometimes the knowledge flows one way, sometimes the other. We realize it’s basically different pieces of the same puzzle. I can solve in captivity some issues the field-workers can never solve, and they can see natural behavior I might never see in captivity. We need each other to arrive at a full picture of a species.

Leviton: Don’t the field-workers in primatology have the same problem that anthropologists have — that their own presence influences the behavior of their subjects and skews the data?

De Waal: Yes, in the field someone might work on baboons and conclude that they very seldom suffer predation, but it’s partly because the researchers’ presence scares away the predators. Pristine environments don’t exist anymore, and the human presence affects everything.

It’s the same in captivity. We influence the animals there, too. But captive research has advantages in some situations. In the field, if there’s a big fight involving ten chimps, most of the participants will disappear for long periods, and researchers have to reconstruct what happened from clues. There’s a lot of speculation there. In captivity I can see the subjects at all times. If there’s a fight, I know exactly how it started and ended.

Leviton: How is your facility designed to let you observe?

De Waal: The chimps live in a large outdoor enclosure with grass and a climbing structure. We have a building and can try to call them in by name, but they come only if they want to come. We can’t force them. The building has food and air-conditioning, so there are certain incentives for them to come inside. They usually stay for less than an hour. Our big challenge is to get certain individuals to come in. Maybe we want A and B to do a test, not C and D. But A has a big fight with B, so that’s not going to happen today.

Once they are in the building, we offer touch-screen tasks or a cooperation task, where they can give each other tokens or food. After the experiment, we send them out again. Our experiments never involve anything painful or problematic. If we did that, they would never come inside again! [Laughs.] We want them to leave in a good mood.

Leviton: Can they decide to come in themselves when they want to?

De Waal: We haven’t managed to do that. We have to let them in. But at the Kyoto Primate Research Institute, the chimps live in an open area and can come in anytime to work on a computer. And the researchers have a camera at the computer, so they know who is generating the data. The chimp might work for ten minutes, then leave.

Chimps love computers. You don’t even need to reward them with food to get them to use one. When we first started using computers, we didn’t have touch screens; we had joysticks. We started very simply. For example, there would be a big red dot on the screen, and the chimps would use the joystick to move a cursor to the dot. As soon as they did, they got a reward. From there you move on to more-complex tasks.

Some have argued that the move from a hunter-gatherer way of life to agriculture and the domestication of animals was the worst decision Homo sapiens ever made. It profoundly changed our relationship to animals.

Leviton: The ethologist Konrad Lorenz, whom you call “the maestro of observation,” believed love and respect were necessary conditions for doing effective investigations of the lives of animals. What did he mean when he urged “holistic contemplation” of other species?

De Waal: Biologist E.O. Wilson, who studies ants, has said there are two types of biologists: The naturalists, like Lorenz and himself, who want to understand the whole organism in all its ecological relations, cognition — everything. And the specialists, who want to know one thing — for instance, what is the best reward schedule for a pigeon to learn a specific behavior? The animal itself and everything that comes with it is of no particular interest to them.

We have a lot of specialists nowadays, and I find it a little disturbing to meet a student who’s going into the field with a very specific hypothesis to test. I always ask, “Why would you have that hypothesis before you’ve even seen the animals? Why don’t you just absorb what they do, and then develop your ideas about them?”

What Lorenz meant by “holistic contemplation” is the desire to know everything about another species: how they lay eggs, how they raise babies, what they eat — even if some of it isn’t part of your initial interest. Everything you learn, placed in the bigger context of the animal’s life, makes it more interesting, in my opinion.

Most primatologists really love their animals and are passionate about their lives. But you sometimes also meet scientists who don’t particularly like their animals. These people do exist. They’re very rare among primatologists, though.

It also helps to be open to surprises. That’s true of all sciences. People who keep their eyes open pick up on things that are new and are ready to dive into them. Other people go around with blinders. They have a theory, and everything has to fit into the theory. Everything that falls outside the theory, they don’t see. Most of us are open-minded.

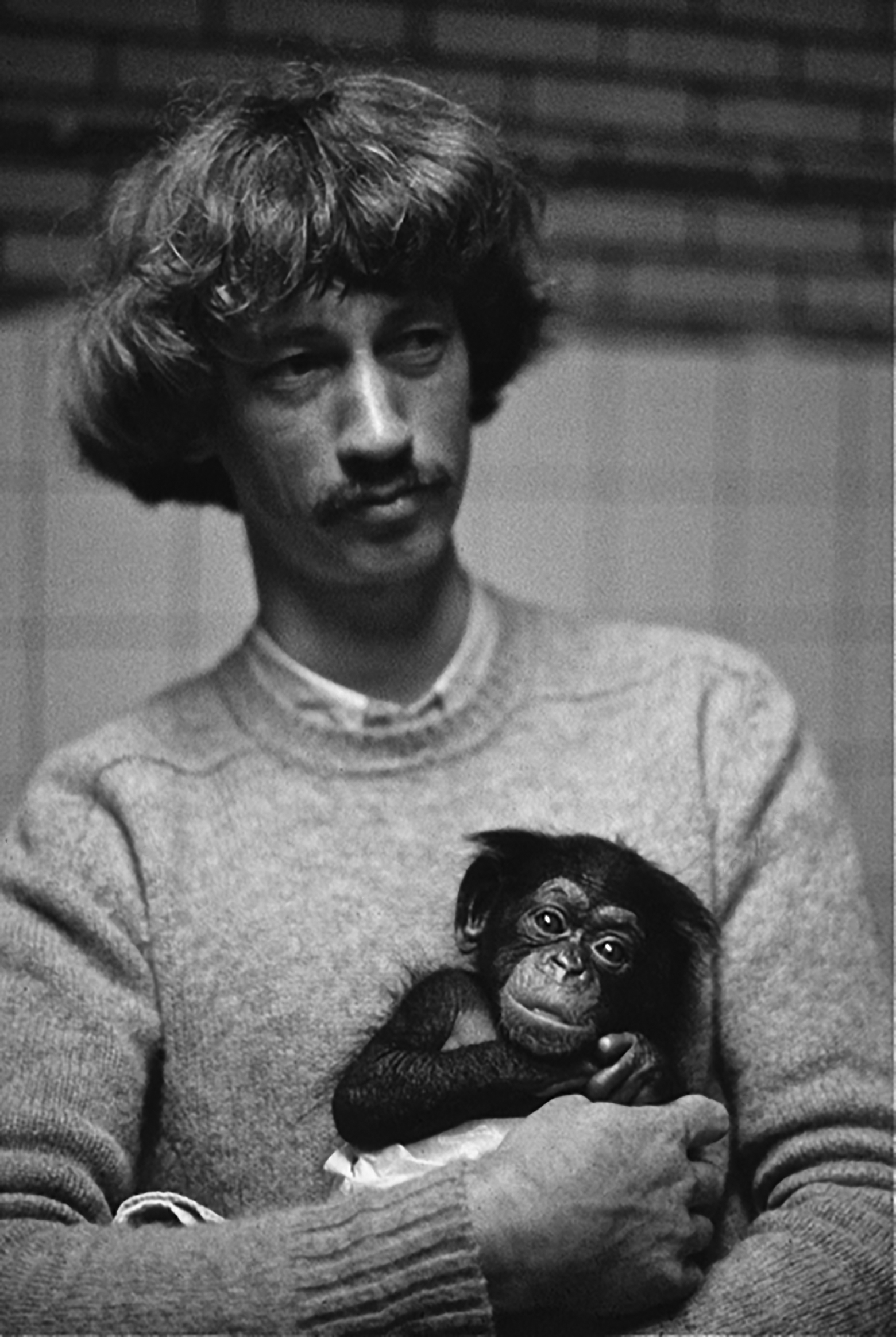

De Waal holding the baby chimpanzee Roosje in 1979.

Courtesy of Desmond Morris

Leviton: Did you have that type of open-minded curiosity when you were a child?

De Waal: Yes, I always had animals as a child — fish and salamanders and birds and mice. I read everything I could about them, at a time when there really wasn’t that much to read — at least, in the Netherlands. When I went to the university as an undergraduate biology student, I was disappointed because all I saw were dead animals. They had us cut up rats and other animals, and plants also. I saw the inside of animals but not their behavior. For my doctorate I went to the University of Utrecht, where I began to study with Jan van Hooff, and I eventually wrote my dissertation about the behavior of macaques.

Leviton: As a child I had pets like fish and turtles, but their deaths really bothered me. In some cases — like when my guppy gave birth and gobbled up her offspring — I was truly horrified. It put me off having pets for the rest of my life. You must have seen a lot of violent behavior studying animals. How do you deal with it?

De Waal: It’s true. Chimps can be violent, even brutal, with each other. They can kill each other. We’ve had it happen. I see this as being part of nature. After my last book, Mama’s Last Hug, which is about animal emotions, I’m often asked if I eat meat. I do. I know very few vegetarian or vegan biologists. I think it’s because we see all kinds of animals eating each other. We don’t find it morally reprehensible; it’s just how nature works. Now, the treatment of farm animals — that I see as a problem. But the eating part, no. The lion eats the antelope. We like the lion, and we like the antelope. This is just the way it is. You have to get used to it.

Leviton: I guess I see this as part of a larger question: Even if we evolved to eat meat, can’t we use our moral sense to overcome that part of our nature?

De Waal: I could see a nutritional argument, an ecological argument, or an animal-welfare argument for vegetarianism, but the eating of meat is not intrinsically immoral, in my opinion. As a biologist, that’s how I look at the world.

One of the convenient things about behaviorism was that it simplified the moral question by claiming animals were dumb. Animals didn’t have emotions, cognitive processes, consciousness. So you could do whatever you wanted with them: keep pigs in tiny lockups, put a bolt into the cow’s head. The moral convenience of behaviorism may be why it lingered for so long, even though it didn’t have much of a scientific basis.

How much we know now about animal cognition and animal emotions is uncomfortable for some people. It does mean we need to pay attention to how we treat animals.

With the coronavirus we have another interesting issue: how we eat wildlife. Ecologists and conservationists have been saying for fifty years that we shouldn’t be eating everything on the planet. Animal diseases can jump to humans with disastrous results. Turns out it might not be so good for us to treat animals like shit.

Some have argued that the move from a hunter-gatherer way of life to agriculture and the domestication of animals was the worst decision Homo sapiens ever made. It profoundly changed our relationship to animals. If you think about it, the hunter has respect for the animals he hunts. He knows how good they are at fighting back, how good they are at escaping; that you will never find them if they don’t want to be found. The farmer, in contrast, is in a dominant position and loses perspective. Small farmers may still be close to their animals and know them by name and so on, but on these big factory farms? No. Agriculture has not helped the human-animal relationship.

Leviton: We give a lot of attention to chimpanzees, but bonobos are just as close to us genetically. We share about 98.7 percent of our DNA with them. Some people find them more interesting to study.

De Waal: They are equally as relevant as chimpanzees, because they are equally close to us. You know, I’m partly responsible for making bonobos so popular. I described their sex lives, the way they make up after fights, and things like that. Still, there is a group of scientists who want to put the bonobos to the side, because the chimpanzee fits much better with their violent scenarios of human evolution. According to them, the history of humanity consists of eliminating others, killing the Neanderthals, conquering the world, being aggressive. If you build your whole evolutionary scenario on the proposition that humans are violent, males are dominant, and women barely matter, what do you do with bonobos, who are sex oriented and female dominated? They are just too peaceful, gentle, and matriarchal to fit into the myth of humans as “killer apes.” For example, female bonobos rub their genitals, their clitorises, together. I used to hear researchers say, “You call that ‘sex’? That’s just affectionate behavior.” I’d tell them, “If that’s not sex, try doing it in the middle of Times Square and see how fast you end up in jail!” [Laughs.]

Many female primatologists love bonobos. Among the general public, bonobos are popular especially with women and the LGBTQ community, and for good reason. But other researchers ignore bonobos and downplay the amount of cooperation in human societies. For example, Steven Pinker wrote a book called The Better Angels of Our Nature, in which he argues that humans have become less aggressive over time, thanks to civilization. That story makes sense only if we were very aggressive to begin with. To make his point, Pinker uses the chimpanzee as his main example of inherent primate behavior. He describes all the horrible things chimpanzees do to each other. He pushes bonobos aside because they don’t fit his story line. But if we started our theory of human development with bonobos, it would refute his scenario, because we’d be seen as inherently more peaceful and cooperative from the start.

It’s not all peace and love with bonobos, though. I recently went to Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to visit the biggest bonobo sanctuary in the world, Lola ya Bonobo. The name means “Paradise for Bonobos” in the Lingala language. All the groups there are dominated by an alpha female. You might think these females would be pleasant and nice, but they are very strict. They punish bonobos who don’t act right. The males have a hard time and will get away to a different part of the sanctuary if the females are not in a good mood.

Leviton: What does it mean to call a primate an “alpha”? Does it differ from the way the term is used in popular culture?

De Waal: The phrase “alpha male” was introduced for wolves by Rudolph Schenkel, a Swiss ethologist, in the 1940s. In my book Chimpanzee Politics, I describe alpha males as leaders who keep the group together, keep the peace, and build alliances. They are empathic and often act as the “consoler-in-chief,” interceding in fights and sticking up for the underdogs.

Now, in the business world, we see all these books about how to be an alpha male: basically, how to beat up your opponents, how to make them feel you are the boss, and how to attract women (who supposedly flock to these types). I sometimes speak to business groups and have to remind them that an alpha male or alpha female can have many different personality types. They can be bullies or coalition-building experts. They are not always the strongest physically. In my TED Talk about this, I speak about the chimpanzee Amos, an alpha male who got sick. He was liked by the other chimps, and while he was ailing, they brought him food and propped him up with the material they used to make nests. They respected him even when he was vulnerable and his days as the alpha were coming to an end.

Not all alpha males have such an easy time of it. They might be violently deposed. That’s one of the costs of being the alpha: others want your position. Sometimes we see old males who are no longer the alpha but still have considerable power behind the scenes, so to speak.

Chimpanzees who want to overthrow an alpha often become very generous in the months before their big move. To gain support within the group, they begin to tickle the infants, even though they’re not usually interested in them. It’s like politicians who kiss babies during the campaign.

Leviton: The chimp you named Mama was a very successful alpha female.

De Waal: Yes, for forty years she was the queen of the Royal Burgers’ Zoo colony in Arnhem, the Netherlands. My book Mama’s Last Hug is partly a tribute to how extraordinary she was. It’s true the males always dominate in chimpanzee colonies, but I make a distinction between dominance and power. You can have greater physical strength, but that doesn’t mean you have more power. The physically biggest male may not have the skills to be the alpha. He might not make the right friends or cut the right deals. Mama had much more power than many of the succession of alpha males who came and went during her time there. She and the oldest male — who was not the alpha — basically ran the group for decades. You might see this in an office: everyone knows who the bosses are, but one of their secretaries makes most day-to-day decisions. This is why I describe a chimpanzee colony as having “politics.”

Leviton: You coined the word anthropodenial, which is the opposite of anthropomorphism.

De Waal: I developed the word because anthropomorphism had become the insult of choice aimed at people like me, who talk about animal cognition and emotions. If I said a dog showed jealousy, they’d say, “Don’t be anthropomorphic. You’re always ascribing human traits to animals. Your dog cannot be ‘jealous’ — that’s a human term.” I always felt that, for apes, anthropomorphism is irrelevant. They are obviously human-like in their behavior, their anatomy, their brain structure. I don’t see the issue with using human terminology to describe them. So I had to find a counterword, to describe many scientists who were in denial about the similarities between species.

Psychology has really changed, though. Neuroscience has shown that the brain of a rat and the brain of a human have similar qualities. So psychologists have shifted their position.

But anthropology still emphasizes human specialness. Anthropologists hold meetings about what makes humans unique — they use the word successful, as in “Why are humans the most successful species on earth?” They don’t say “superior” because that word has negative associations now, but successful means pretty much the same thing. I don’t think humans are so successful, by the way. We’re destroying the planet.

Leviton: Is this connected to why you don’t like to call other animals “nonhuman”?

De Waal: I’ve never liked that word, as if they are unfortunate creatures who have the bad luck to be not human — as if we are the center of the universe. Why not refer to ourselves as “nonelephant”? [Laughs.]

Mama at the Royal Burgers’ Zoo, Arnhem, the Netherlands.

Leviton: Speaking of elephants, you mentioned that their brains have three times the neurons of human brains. What else is special about elephants?

De Waal: They are very emotional creatures. I got involved with them because I had this hypothesis that higher levels of empathy have to do with a higher level of self-awareness. The basis of empathy is that you are sensitive to the emotions of others. You find this in your dog, your cat — all kinds of animals. But higher-level empathy is when you can understand and appreciate what another creature is going through. In humans that capability starts to develop around the age of two, when we first recognize ourselves in the mirror. Apes can be empathetic as well, and we have lots of evidence that an ape can recognize itself and be self-aware.

For years elephants were given mirror tests, but they always failed. This turned out to be because the mirrors were too small in comparison to their bodies. Together with Josh Plotnik, who’s now a professor at Hunter College in New York City, I set up jumbo-sized mirrors, and we were the first to demonstrate that elephants did recognize themselves.

It’s impressive what else elephants can do. A recent study Josh did showed that elephants can smell the difference between a bucket containing 150 sunflower seeds and one holding 180 seeds. We say they have “a nose for counting.” They have forty thousand muscles in their trunks alone and more genes dedicated to the sense of smell than any other species in the world. In Thailand, where young elephants are often outfitted with bells around their necks to announce their presence to villagers, the elephants sometimes muffle the bell by stuffing grass inside. That shows real imagination. In an open-air sanctuary in Thailand, a female named Mae Perm acts like a seeing-eye dog for a blind elephant friend named Jokia.

Leviton: How do they deal with loss? Do they show grief?

De Waal: You can expect to see grief in every animal that develops attachments, even fish and rodents. When one member dies, there will be a response to that loss. In elephants it’s a very deep one. In the wild they return many times to the place where the bones of their deceased lie. So elephants have this very long, lingering attachment. In other species it tends to be shorter. Among chimpanzee females, when one of their infants dies, they carry the corpse around for weeks, sometimes until it completely falls apart. Of course, between mother and infant you expect to see these attachments. But elephants show it toward adult members of their herd.

Leviton: Do you think animals are aware of the possibility of their own death?

De Waal: Many animals understand that the death of others is irreversible. Apes have a strong reaction to the death of other apes. They know the dead are not going to spring to life anymore. Whether they extrapolate from there and realize they, too, will die one day — we really have no evidence for that. I doubt it actually. Sometimes, though, when I see how animals fight to stay alive, I suspect they know something about it.

Leviton: For a long time, researchers believed animals had no sense of the future. Do they?

De Waal: When Köhler’s chimps stacked boxes and climbed up with a stick to reach a banana, they showed future planning. Lots of experiments have demonstrated similar results. Orangutans and bonobos will keep a tool to use in the future. Given a choice between a tool they can use right away to get a food item and another that will be useful later to get much more food, they will opt for the bigger, delayed, reward.

Scrub jays hide caches of food to harvest them later. The British ethologist Nicky Clayton did a wonderful experiment that showed how the jays planned for breakfast the next day, moving food to a different location if another jay watched them hide it the first time. They seemed to understand the cache was safe only as long as the information was hidden from other birds.

In the field chimpanzees have been observed carrying tools for several miles to termite hills, where they use them to poke around for termites. That indicates they had a plan to go to the termite hills to eat. Also a female bonobo named Lisala took a heavy rock on her back and walked with it for fifteen minutes to a place where she could use it to crack nuts. If she wasn’t planning to do this, why carry the rock around with her?

Anthropologists hold meetings about what makes humans unique — they use the word successful, as in “Why are humans the most successful species on earth?” . . . I don’t think humans are so successful, by the way. We’re destroying the planet.

Leviton: One of your most popular experiments is about the reaction of capuchin monkeys to unequal rewards. It’s been viewed more than 16 million times on YouTube. What did you find out?

De Waal: It might be the most-watched animal experiment in history. I think it’s been shared millions of times, because everybody sends it to their boss to argue for a raise! [Laughs.] It’s important to understand that when you test a very social animal on its own, you will often get bad data, because the subject acts differently than when there is another animal there. When the behaviorists experimented on rats by themselves in mazes, they were ignoring the fact that rats are highly social animals. For twenty years I had a lab with capuchin monkeys, and I learned quickly that they don’t like to be alone. They want to hear their group-mates, their family, and it’s even better if one is sitting right next to them. So we always tested them in pairs.

A student of mine, Sarah Brosnan, noticed a monkey was paying attention to what the other monkey was getting as reward for the tasks we set for them. So we devised an experiment where the monkeys were in adjoining cages and could see each other, and we gave them both the same task, but as a reward we gave one grapes and the other cucumber slices. To capuchins grapes are ten times better than cucumber. The monkey that was rewarded with cucumber threw it back at us when he saw the other guy got grapes! Interestingly, if you do the same experiment with chimps, the one who receives grapes will sometimes refuse them until the other chimp also gets grapes. So the chimps go one step further than the monkeys. Chimps know they are going to upset their partner if they eat grapes in front of one who only has cucumber. They understand it will damage their relationship. Humans will do the same thing when given a fairness test.

There’s an economics experiment called the ultimatum game, in which the first player is given money and told they can share as much as they want with the second player — but the first player knows that if the second player rejects the offer, then neither gets anything. It turns out in most cultures people offer a fair split, fifty-fifty. We played this game with chimpanzees. It was hard to explain the rules to them, but we did manage to work it out. We also ran the experiment with five-year-old children. And the apes did exactly the same as the children: they tried to equalize the outcomes. I see little difference between apes and humans when it comes to assessments of fairness.

Leviton: The design of tests is so crucial. A study recently showed that out of twenty-eight famous psychology experiments, including the famous Stanford Prison Experiment, only fourteen yielded the same results when run again. It turns out some of the most seminal experiments were poorly designed, or the data were tampered with.

De Waal: We often see poorly designed experiments, and people often get only the results they expect. They expect the children to do better than the chimps, and, guess what, they do. In 2005 there was an experiment that claimed to show chimps don’t care about the well-being of others. The researchers set up an apparatus where chimps could pull a lever to get food either for themselves or for both themselves and their partner, and, according to the researchers, the chimps made no distinction. We looked at the videos and the data, and we couldn’t understand how the pulling mechanism worked. If we couldn’t understand it, how could the chimps ever figure it out? That’s why they just pulled randomly. We set up an experiment with tokens, which are much easier for chimps to understand, and now we have five or six studies that clearly show they do care about their fellow chimps.

Other researchers immediately jumped on our fairness experiment with the capuchin monkeys and started to try to replicate it. There were some that failed, and they concluded our result was incorrect. But we saw that their experiment wasn’t the same. They didn’t require the monkeys to do a task. We decided to see what would happen with our monkeys if we just gave them grapes or cucumber — no task. They didn’t respond negatively to that. It has to be an unfair reward for work. So these quick-and-dirty replications sometimes don’t test the same thing. Our experiment has now been properly replicated with dogs, too.

Leviton: What would happen if the tasks were uneven in difficulty? Would the monkeys conclude the more difficult task deserved the grapes?

De Waal: We did that. The monkeys didn’t respond to it. Keeping track of the relative difficulty of a task was too tough for them, it seems. They apparently don’t think, “He did twice the work, so he deserves twice the reward.” It’s always a challenge to make the experiment salient for them. They have to be able to discover a difference.

Leviton: You’ve said that human society can’t function without “triadic awareness.” What is it?

De Waal: That’s an understanding of the relationships among others. If there are three people — you, your friend, and me — you might understand your relationship with me, and your friend might understand his relationship with me, but do I understand your relationship with him? That’s triadic awareness. If I see a child walking near my home, I usually know who the parents are and what family the child comes from. I’m aware of the child’s other relationships. If you go to a party, you know the host, X, used to be married to Y and is currently living with Z. This is how societies and cultures are formed.

Leviton: Do animals have culture?

De Waal: We do a lot of studies about the transmission of knowledge and habits among animals — how animals learn from each other. The first major example was the potato-washing study in Japan in 1948: Kinji Imanishi and his students began to study monkeys on Koshima Island. He thought that if animals could learn from each other and groups could differentiate themselves, they could have cultures.

His students discovered that a little female monkey named Imo took sweet potatoes, still covered with dirt from being dug up, to the stream to wash them. Her young friends soon followed her example, then the adults, and before long all the monkeys were washing their potatoes. Some even took them to the ocean — to add some salt taste, it appeared. That was the first evidence among monkeys of what we call a tradition, which is a part of culture. We now have lots of examples — birdsongs, whale songs, and all sorts of tool use — of animals learning from each other. Neuroscientists have even found that the brain development of songbirds is altered depending on the songs they learn. So, yes, we now speak about animal culture.

Leviton: Can you explain “mirror neurons”? Some believe their discovery is as significant as the discovery of DNA.

De Waal: This is a type of neuron that responds similarly whether I move my hand to grab something or I see you move your hand to grab something. Your actions are encoded by that neuron in the same way as my actions. We think mirror neurons help us understand each other’s movements. They are usually invoked to explain imitation and empathy, but how they work is not entirely understood. Some people think they are overhyped, meaning we refer to them in many circumstances where they might not be relevant. For me, it’s interesting that they were discovered in macaques. Imitation and empathy were for so long considered uniquely human features, and then we discovered mirror neurons in monkeys.

Leviton: So if you show signs of anxiety, my mirror neurons react as if it might be happening to me?

De Waal: Well, there’s a lot of facial mimicry going on. That’s one of the processes of empathy. Often without knowing it, we adopt the facial expressions of others. If we are talking to someone who’s sad, we’ll make a sad expression as well. Laughter is “contagious” in a similar way. The Swedish psychologist Ulf Dimberg was the first to demonstrate this. In the 1990s he put people in front of a computer screen, attached electrodes to their faces, and found that they automatically mimicked the expressions they saw on the monitor — even if the pictures flashed for only a fraction of a second. The subjects thought they were looking at pictures of scenery; they couldn’t even see the subliminal faces. But their own faces took on the same aspect. Subjects who mirrored the smiles of others felt better after the session than those who were shown frowns. I talked to Dimberg one time, and he said that when he first made the discovery, he couldn’t publish his findings, because psychologists had decided empathy was a conscious process. His experiments showed it was involuntary, which didn’t fit the current thinking. At the same time, I was publishing my book Good Natured, which ran into some resistance for the same reason: because empathy was considered a cognitive feat, and my conclusions didn’t agree with that. We like to believe we “think” our way through life, when many of the ways we react are not a result of cognition but rather a rapid response of the body.

Leviton: Can you describe your relationship with the female chimp Kuif? You bonded with her after helping her raise her first surviving offspring.

De Waal: I was a student when I first worked with Kuif. Initially she was not particularly friendly toward me. I think she tried to dominate me — a typical chimp behavior: whether male or female, they want to have the upper hand. She shared a night cage with Mama, the alpha female we talked about earlier. They were best buddies. Mama never tried to dominate me, maybe because she already had such power in the colony.

Kuif had lost two or three babies due to insufficient lactation. Each time, she went into a deep depression that was horrible to watch. We were at the point where we thought she shouldn’t get pregnant anymore. Then a baby chimp named Roosje became available whose mother was not able to take care of it, and we decided to have Kuif adopt the infant. We would teach her how to bottle-feed the baby. That was not too difficult, because chimps are natural tool users. (We did have to teach her not to drink the milk herself.) We kept the baby chimp on our side of the bars, and Kuif would feed the baby from the other side.

After six weeks or so, feeling confident she could handle it, we put the baby chimp in the straw of Kuif’s night cage. She didn’t go near it, didn’t even want to approach it. She kept looking at us. I realized she was respecting our rights — she considered the chimp our baby, and in chimp society it’s certainly not well regarded to take the baby of someone else. But we kept telling her to take the baby, and at some point she went to it and put it on her belly, and she did the bottle trick very well, and she never left it after that. Three times a day she would bring the infant in from the island where she lived to do some bottle feeding, and then we’d send her out again. I became her best friend. She was so grateful. She also went on to have babies of her own and raised them on the bottle, too. She was a very successful mother until she died about ten years ago.

Leviton: I don’t want to let you go until we talk about octopuses. They are quite extraordinary, aren’t they?

De Waal: Yes, they are soft-bodied cephalopods, or “head-footed” animals. They have a decentralized nervous system with a huge neural network, and their arms have two thousand suckers, each with half a million neurons — on top of their 65-million-neuron brains, the largest of all invertebrates. Their brains are distributed up and down their arms. They can open bottles with childproof caps and are tool users in lots of ways.

The mimic octopus, found off the Indonesian coast, is a camouflage expert. It impersonates other species, changing color and shape and doing undulations on the sea floor to resemble local plants or fish. It doesn’t sound like genetic programming to me. I assume they first have to see another species to figure out how to mimic it. Roger Hanlon, of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, is one of the experts in the field. And the philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith wrote a book called Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness.

Leviton: We think of humans as “successful,” and then we encounter an animal like the octopus, with its amazing abilities, like something out of science fiction.

De Waal: The DNA studies on octopuses recently came out, and some say it’s like looking at alien DNA — whatever that might be. [Laughs.]

Leviton: Perhaps you were just having some fun, but you’ve said that if you were reincarnated tomorrow as an orangutan, you’d rather live in a zoo than the jungle. Why?

De Waal: People think that freedom is everything — especially Americans. It’s the “land of the free,” you know? I often hear from critics of zoos that the animals are not free. Well, in the wild, freedom means you can get eaten, and there are all these parasites, and you might starve to death because you’re not as successful at hunting as another. So freedom is not always so wonderful.

If I were an orangutan one hundred or two hundred years ago, I’d want to live in Borneo. That would be fine — especially considering what zoos were like in those days. In the last twenty years, however, a hundred thousand orangutans have disappeared in Borneo, with the forest going up in smoke and the farmers shooting all the orangutans who flee. Under those circumstances I’d give up my freedom, pick a good zoo, and have an easier life.

I think people underestimate how hard the life of a wild animal is. They think it’s all wonderful. If you’re a running animal like a zebra, or a swimming animal like an orca, you are definitely better off with a lot of space around you — that’s for sure. But other animals can have perfectly good captive lives.

People have tried many times to take primates from zoos or other facilities and put them back in nature. Sometimes they succeed, which is wonderful, but many times it goes wrong. In his book Unwitting Travelers, Benjamin Beck describes many cases where the chimp is released into the wild and two weeks later comes back to live with the humans. The forest is not so easy. A primate born in the wild might reacclimate, but for animals bred in captivity . . .

An anthropologist once wrote that if you take twenty people and release them in the forest, they will not survive, but twenty monkeys will. That’s the huge difference between humans and monkeys, he said. But if you take twenty monkeys from a zoo and send them to the forest, they’re going to die as well. We know that. Those monkeys don’t know how to live in the forest. They don’t know where the snakes hide, where the food is. They know nothing. There is an animal culture. They need the transmission of knowledge for survival just as we do.