It was ten o’clock on a Friday night in San Diego when my boyfriend said, “Let’s go to Vegas.”

We were unemployed students, broke except for his financial-aid money, but he assured me our winnings would more than cover the cost of the trip.

I had never gambled before, having been raised in a family that considered gambling a lower-class behavior (along with divorce and drinking). But I was taking charge of my own life now, and I decided there was such a thing as “responsible” gambling.

When we arrived at the casino, buzzers and bells and lights saturated my senses. We headed for the blackjack table. I was stunned by the minimum bet: twenty-five dollars. “Trust me,” my boyfriend said. I watched as he won twenty-five hundred dollars in fifteen minutes. It was that easy. Why hadn’t I tried this before?

I was ready to leave, but instead we went to the next table (where he lost) and the next (where he won a little) and the next (where he lost again). Our pile of cash was shrinking.

We hadn’t slept in more than twenty-four hours, so we got a hotel room. I collapsed into bed, but my boyfriend whispered that he was going to play a few more tables. I awoke each time he came back to the room for more money.

By morning our winnings were gone, but he wasn’t done. Shaken but still a believer, I ran to the ATM to withdraw a hundred dollars. Each time I returned to the ATM, I thought of how easily he’d won in the beginning.

Eventually there was nothing left. We had just enough money to buy gas for the long drive home. According to my boyfriend, it was all my fault: I had jinxed him. He’d never lost before.

Anna Marie Van Bonn

Flossmoor, Illinois

I had my first lesbian affair in my junior year of college. No one from my hometown knew about it. During spring break, I decided to tell Wendy, my best friend since seventh grade. If anyone could accept me, it was she. Still, I was nervous. There was always a chance I’d lose her friendship.

Wendy and I were riding on the train downtown when I proceeded to tell her about the affair, omitting names and pronouns. Eventually Wendy asked a question using the word he. “Well,” I replied cautiously, “the ‘he’ in this case happens to be a ‘she.’ ” Wendy stared hard at me for a minute, then turned and looked out the window. I was shocked and hurt but said nothing more.

Over the next fifteen years I tried unsuccessfully to gain Wendy’s acceptance. Though she expected me to support her through a string of boyfriends and eventually a marriage, she kept her distance from anything related to my love life. When I invited Wendy to meet my partner, who had moved across the country to live with me, Wendy replied, “Can I pretend the two of you are just friends?” I laughed, thinking she was joking. Then I realized she wasn’t.

I later wrote to Wendy and explained that I was still the same person I’d always been and expressed disappointment that an intelligent woman like her would choose to nurture her prejudices rather than examine them. I told her that I needed her to respect me, or the friendship would be over. In her reply Wendy was furious that I would threaten to end our friendship because of this and bitterly assured me that I would never find another friend like her.

Amy L.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

My father was a fun-loving, hardworking guy. He drove a semi and lived for Friday-night “club meetings,” when my parents and their friends would get together for card games. The women would play Tripoley and watch television. The men would gather around the kitchen table with their cocktails and play pinochle, joking and laughing long into the night. The money didn’t matter as much as the thrill. They were healthy and strong, at the peak of their game.

One by one the members of the Friday-night club died, until my dad was the lone survivor. He started going to the casino. Even after his health declined and he began to use a wheelchair, he could still play cards. His gambling debts mounted, but he continued until shortly before his death. Those card games were his connection to the life he had lived, those Friday nights in a house full of friends.

Cynthia Durante

Okanogan, Washington

My uncle always gave the best presents, like a wind-up toy motorcycle and a handmade silk box kite. In 1949, when I was ten, he gave me a present I didn’t recognize at first, but I could tell from my mother’s gasp it was something I wasn’t supposed to have — and therefore a really good present. It turned out to be a miniature roulette wheel with a green felt betting cloth and a pamphlet on rules and odds. I quickly tested the wheel to see if the odds given were accurate. Several hours later they were confirmed, and I put the wheel in the closet.

One summer day, looking for something other than the usual board games to play with my friends, I pulled the roulette wheel out of the closet and showed them how to bet, using beans and matches. It sparked everyone’s interest, and we soon switched to pennies. A few weeks later I had several coffee cans full of coins.

When the kids started grumbling about not winning, I switched to blackjack. The coffee cans continued to fill up. Soon most of the kids within a three-mile radius were scrounging around for Coke bottles to turn in or lawns to mow so they could get back in the game. We played on a table in the garage with a light hanging over it. I wore a yellow vinyl eyeshade and kept semiregular hours.

I was in the middle of a deal one Saturday morning — the ten-to-twelve shift — when the garage door opened, and there stood a dozen adults with wide eyes and slack jaws.

I was forced to close my casino, but since the parents couldn’t figure out who had lost what, I got to keep the money.

To this day I don’t go to Vegas. I don’t like to be on the other side of the table.

Doug Colville

Cotati, California

Unlike my mother, I’ve always played it safe. When she took me clothes-shopping, she liked hot pink. I chose brown. At five I knew I wanted to be a nurse. She was still not sure what she wanted to be. At twenty I met the man I would marry. At twenty she had joined the navy.

Before my wedding I thought it would be good to travel with my mother. I wanted to see Paris. She booked us on a cruise to Bermuda. On our last night I agreed to go to the casino with her. We put one quarter in the slot, and fifty-some quarters came shooting out! Overwhelmed with our good fortune, we called it a night.

I enjoyed telling friends the story of our good luck, until the first time my mother heard me tell it, when she quickly corrected me. “Oh, no,” she said. “After you went to sleep, I went back and lost it all.”

Lucy G.

Florence, Massachusetts

I grew up in Las Vegas and worked in twenty different casinos on breaks from college. I’d walk the floor or sit in a booth, making change for people playing slots.

One place I worked was the then-snazzy Riviera Hotel, the first casino to have its own wedding chapel. One night I saw a groom sitting at a nickel video-poker machine with his bride on his lap, both of them still in their wedding outfits. She happily supplied him with nickels from a plastic cup while she ate a hamburger with ketchup.

I also worked at the Aladdin, which had gone bankrupt and was always on the verge of closing. I had the graveyard shift and wandered the floor of the once-beautiful casino, a change belt at my waist. Sometimes a Marilyn Monroe impersonator would float in, so beautiful and blond and elegant in her white dress. She’d quietly order drinks and play the slots, going through racks of silver tokens, unwinding after a long night.

S. Solomon

St. Paul, Minnesota

Our wedding was set for February 1. We’d already booked the church, bought the rings, and sent out the invitations. Then, two weeks before Christmas, my fiancé, Alvin, disappeared for a day. I knew right away he’d gone to Las Vegas for one last gambling fix. I was angry, and my stomach churned with anxiety. How much would he lose this time? Could you stop a wedding once it had been planned?

Late that night, Alvin returned home with a sparkle in his eyes. “Before you say anything, take a look at this.” He handed me a check for thirty-four thousand dollars from Harrah’s casino. “I won it,” he said, elated. “This will be a fresh start for us. We can pay off all our debts. It’s the best wedding present anyone could have given us.” But I knew he was deceiving himself.

Ten days later Alvin went back to Vegas and gambled away every last penny. When he returned, he didn’t need to tell me the news. I could tell from his hunched shoulders and dejected expression. A small part of me felt relieved, because I knew if Alvin didn’t have to pay off his debts the hard way, he’d never learn. He kept apologizing and saying he never wanted to hurt me. “This was the last time,” he promised.

On our wedding day, after I’d put on my beautiful dress and checked my makeup, I peeked into the sanctuary and noticed another door at the back of the building. I had a mad desire to run out that door as fast as I could. But then I thought of Alvin waiting for the ceremony to start, of my parents and sisters who’d come so far, and I knew I couldn’t do it. Instead I trusted someone I knew could not be trusted. I walked down the aisle like the good girl I’d been brought up to be. I took a chance.

Louise E.

Venice, California

My devout Catholic mother-in-law believed in miracles. She knew that God could touch you with his grace when you least expected it, and she was going to give God every opportunity. She played her lottery numbers — birthdays and anniversaries — each week. Neither repeated failure nor talk about the odds deterred her. She was sure that riches waited just around the corner. Besides, she had heard stories of other winners: friends of friends, the daughter of her hairdresser’s cousin. Her own sister had won five thousand dollars on The Big Spin.

My mother-in-law died never having hit the jackpot. Driving to her wake, my wife and I passed a drugstore with a glowing neon Lotto sign. In honor of the deceased, we pulled in and bought fifty scratch-offs, then distributed them at lunch to all her relatives and friends. Their faces glowed in anticipation as they scraped the tickets. Most were losers; a couple had minor wins. Oh, well. There was always next week.

John Unger Zussman

Portola Valley, California

Before I was born, my mom worked in California as a dental assistant. On New Year’s Eve 1968, the dentist she worked for took the whole office to Las Vegas for a party. The staff piled into a rented limo and drank martinis as they headed for the Dunes Hotel. My mom went along, though she didn’t drink or gamble. She had other plans.

That night in Vegas, when the dentist was tipsy, my mom flirted with him and went back to his room. They had sex only once. She says she kept her eyes closed the whole time and prayed she would get pregnant. It worked.

Nobody knew that my mom’s best friend, Dee, was actually her lover. They wanted a child and had chosen the dentist — a smart, handsome, and (most important) married man — to be the unwitting sperm donor. As soon as my mom started to show, the dentist asked if he was the father. She swore he wasn’t and quit her job.

Eighteen years later, after I’d insisted on meeting the man from whom I’d inherited my passion for numbers and horse racing, the dentist finally found out the truth. I met him at a card house in Los Angeles, and we got to know each other as we played blackjack side by side.

Gina G.

Eugene, Oregon

My husband and I have been married for twelve years. He is seventy-five; I am fifty. When I met him, I’d been through decades of abuse at the hands of a volatile mother, an absent father, and the inevitable controlling men who’d followed. He gave me peace and the strength to get the counseling and medication I needed. We had a happy marriage.

When he entered his seventies, though, the passion went away. We tried Viagra and porn. We even briefly considered bringing a third person into the bedroom, but we didn’t know how to go about it. In the meantime I preoccupied myself with work and family.

The day I met Charles was like any other. He came to my place of business to give me a quote for a job. (His wife, of all people, had referred him to me.) His tall frame, gray hair, and blue eyes sent my imagination into overdrive. After that first meeting, I was torn between my sense of loyalty to my husband and a yearning to feel a younger, stronger, fully functioning body close to mine.

One day Charles called, and I confessed everything: how much I wanted him, how I’d agonized over betraying my husband. I had no idea what his response would be. I did not know his marriage was ending.

Being touched at fifty is different from being touched at twenty, or thirty, or forty. At fifty you know your life is passing, your body is changing, and this could be your last chance.

Every time I meet my lover, I take a risk. I am amazed I can lie to my husband so easily about where I’m going or where I’ve been. I tell myself I’m protecting him, and that my betrayal enables me to stay in the marriage. And I will stay. I will not desert him. He will be secure in the knowledge that he is loved and respected.

Every night I say a prayer of thanks that I’ve made it through another day and nobody got hurt.

Name Withheld

My dad’s monthly poker game rotated locations, so that he and Mom hosted it at our house every nine months. It was always a big production, with platters of cold cuts and my mom’s homemade apple pies to eat. We’d insert the leaf in the dining table and tuck extra folding chairs around it. Dad would shuffle a brand-new deck of cards, the plastic just removed. Sometimes my brother, my sister, and I would give Dad the money we’d earned helping him split wood or shovel snow, hoping to get a cut of his winnings.

As the guests arrived — all men Dad worked with at the police station — the house filled with noise and smoke and laughter and playful ribbing. Poker chips clacked on the table. One of the players would rub my head for luck; another would ask me to cut the deck. We kids would watch until Mom hollered for us to come to bed. Dad would give us each a playful swat on the butt as we left. The next morning we’d ask him how much he had won or lost. He’d groan in frustration when it’d been a tough night and lift us up, laughing, when he had won.

Once, as my father left for poker night at another player’s house, my brother, who was eight, pulled some money from his pocket and gave it to my father to bet in that evening’s game. The following day Dad was particularly miserable from the pain of his loss.

A month later, when the game landed back at our home, the guys asked how we’d enjoyed our dad’s winnings from the previous game. My brother looked at my father, and Dad turned away in embarrassment and shame. We never gave our money to him again.

L.N.

Chicago, Illinois

Akiko’s parents had struggled for thirty-five years to hold on to their Japanese identity while finding success in America. When she and I announced our engagement, they weren’t impressed with her choice. I was neither financially successful nor Japanese.

We made the announcement on Labor Day, when her family hosted an annual dinner for friends. The festivities included poker. Being pretty good at cards, I said that I wanted to play. Akiko’s father, Ben, took me under his somewhat drunken wing and explained the rules in broken English.

Most of the players were drunk to the point of being easy marks. Stone-cold sober, nervous, and calculating, I started to win. My victories were met with polite smiles and proclamations of “beginner’s luck.” Ben, however, was delighted and took credit for my skill, having taught me the rules.

Toward the end of the night things grew quiet, and everyone watched Ben and me — the last two players. We were playing high or low to win, and I had one of the lowest hands in the game. When it came time for us each to pick high or low, he generously said, “Micah-san, you go high, I go low, and we split the chips.”

“No, Ben-san,” I replied, “I’m going to beat you.”

We both went low. Ben shook his head. “Sorry, Micah-san. You played good.” He dramatically showed his cards one at a time: ace, two, three, five, and six. I showed my cards all at once: ace, two, three, five, and six. It was a tie. Ben pounded me on the back, and the older folks burst out laughing.

Ben and I get along pretty well these days, but I don’t play cards with him anymore. I’ve already won.

Micah Posner

Santa Cruz, California

I work at a racetrack, taking bets. Three types of bettors come to my window: There are the professionals, who always do their research, plan their bets, and know when to call it a day. They sometimes smile, rarely talk, and mostly just go about their business.

There are the recreational bettors, who start the day with a set amount of cash they plan to gamble and generally stay within that limit. They smile, drink, and have fun. Some are older couples who still dress up to go to the track. The women even wear hats and gloves, just as they did in the forties.

Then there are the desperate gamblers, who are alternately entertaining and pathetic. Each has a tale of woe. “Yesterday I picked the 4-6 at Philly, even though the 4 was 50 to 1. But the friggin’ teller couldn’t get the bet in on time, and I was shut out of a $15,000 payday!” It’s always the teller’s fault. The desperate gamblers also have stories of grand victories. “I had the pick-6 at Belmont last month. Made $106,000. But, hell, it’s only money.”

The “it’s only money” line is delivered cockily whenever they win. When they don’t win, they have no lines. They want to be cool and smart, like the professional gambler, or relaxed and fun-loving, like the recreational gambler, but they can only look like what they are: desperate. They start the day peeling bills off a bankroll and most times end it making two-dollar bets with coins, stinking of booze.

After placing their bets, they stand with their fellow desperate gamblers and yell at the TV screen: “Come on, Five. Come on, Five. What the fuck are you doing? Come on, go, go, go! . . . Shit! What are you doing to me?”

The horses can’t hear them. I wish I couldn’t.

Kevin Kane

Madison, Connecticut

One rainy evening in Berkeley, I was walking home alone, having just broken up with my boyfriend, John. I stopped at a gas station to get a newspaper. I didn’t really want to go home, and it felt good to be in the gas station, with its neon lights and people bustling in and out.

I noticed someone filling out the numbers on a lottery ticket. Although I rarely played, I decided, What the hell. I had three bucks. But it turned out the lottery machine was temporarily off-line, and people were waiting for it to be fixed. The store clerk told us it could take fifteen minutes. I didn’t care. I watched people and tried to ignore displays that reminded me of John; on climbing trips he and I had stopped in many gas stations to buy water, gum, nuts.

Twenty-five minutes later the machine reconnected, and I felt my heart sink. I didn’t want to go home yet. I’d felt comfortable yet invisible standing there.

I heard the rapid clicking as the clerk keyed in my numbers. Then I walked outside, letting the rain mix with my tears. You son of a bitch, I thought. I hope I win the lottery.

Kimberly G. Robinson

Laguna Niguel, California

Until a few years ago, gambling was my favorite pastime. Get me within ten miles of a casino, and I’d start feeling high. This will be my day, I’d think.

My husband gambled with me. When we were losing, we paid outrageous fees to the casino for cash advances on our credit cards. We occasionally recouped our losses, but the money rarely went back into the credit-card account. Instead I would hoard it for our next trip to the casino.

When we’d maxed out every credit card, my husband decided we needed to quit gambling. He would no longer go with me to the casino, he said. I felt threatened: how could he deny me something that brought me such happiness? I continued to go by myself. One weekend I won $5,500. At first I planned to pay down some of our credit-card debt, but instead I gave my husband and my daughter two hundred dollars each and saved the rest for my next visit to the casino.

A week later I lost $1,100 in an hour. It was just not my day. In two more visits I lost the rest. That last night, after several drinks, I cleaned out my checking account. Broke, I begged the casino agent — who had called me at home to entice me to come back — to help me borrow more money. She wouldn’t.

As I drove home in tears (and under the influence), I decided to lie to my husband about how much I’d lost. Then I started plotting my next trip to the casino.

S.M.

Murphysboro, Illinois

As a United Nations human-rights investigator, I was recently assigned to a remote area of an oil-rich country that is being devastated by armed conflict. The rebels are indigenous people who are being wiped out by the government, which is backed by the U.S. military.

The rebels kept track of where my UN colleagues and I stayed, when we traveled, and where we went. They let us know that we were safe from ambushes on the roads where the oil company drove its trucks. Rebels often attacked towns just after we’d left. They had seen my reports and thought I was on their side. They were wrong. I wasn’t on any side: I was working for the peaceful people caught in the crossfire.

In the UN compound, my colleagues drowned their anxieties in alcohol, went to bed late, and had nightmares. I meditated and did yoga and went running along a road, heading into the bush, where women gathering firewood were often raped by government soldiers. Those soldiers also routinely shot innocent people.

One time we were working in a town, and a colleague learned that the rebels were planning to attack government posts there as soon as we pulled out. I wasn’t sure what to do with this information and wrestled with the decision for days. Finally I leaked the rumor to a local official, asking him to warn the police. Then I sent word to the rebels that the army would be waiting for them.

When I told my colleagues what I’d done, they accused me of gambling with our lives. But the attack never came, and today I have a clear conscience.

In our final report we concluded that the native group the rebels belonged to would be gone in less than ten years. It’s now months later, and that report is buried inside the UN. The country’s government is still killing indigenous people. I’ve been told that if I leak the report to the world, my career is over. Again I face a difficult decision. If I take the risk and leak the report, I’ll never be hired again, but at least I’ll feel better knowing I did all I could for the innocent people being killed for oil in that far-off place.

Name Withheld

My father and stepmother had only just retired when my stepmother was diagnosed with cancer. She died within weeks, and my dad moved in with my Uncle Tom in Montana. I was going to college in California at the time, and Dad would send me fifty dollars a month to play the California lottery; if the ticket won, he said, he would split the prize money with me. He also played the Powerball lottery in Montana and told me that I would get half his winnings from that, too. Part of me thought that my father and I might actually win one of these lotteries. He was desperate with grief, and winning would lift his spirits.

Four months later my uncle called and told me that my father had committed suicide by swallowing enough morphine to kill two horses. Two weeks later my aunt called and said my uncle had just won $11 million in the Montana Powerball.

J.C.

McKinleyville, California

On my seventh birthday, my father died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage, leaving my mother to raise five children by herself. She suffered a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized. When she returned home, she medicated herself with bourbon. Her mantra was “We can’t afford it; we’ll never make it.”

Predictably I married a charming man whose heavy drinking seemed normal to me, given my childhood. I was an overachiever and squirreled away every bonus and raise, my mother’s mantra never far from my mind.

Eight years after we’d married, my husband and I agreed that his drinking was excessive. We attended support groups and marriage-counseling sessions. My bank account continued to grow, but my childhood sense of never having enough remained. We lived frugally, and my husband, whose expertise was finance, kept track of our investments.

One day, preparing to leave on a business trip, I went to the bank to withdraw some money from a special business account only I could access. I was informed that I had recently emptied that account — seven thousand dollars — with a check made out to “cash.”

I drove straight to my husband’s office. He had no choice but to tell me the truth: For three years he’d been gambling compulsively. He had doctored our monthly bank statements and maxed out multiple credit cards. He’d forged my name to clean out my account because his bookies were leveling threats at him.

My mother’s mantra had come true: we really weren’t going to make it. I told my husband to give me his house key, and I filed for divorce.

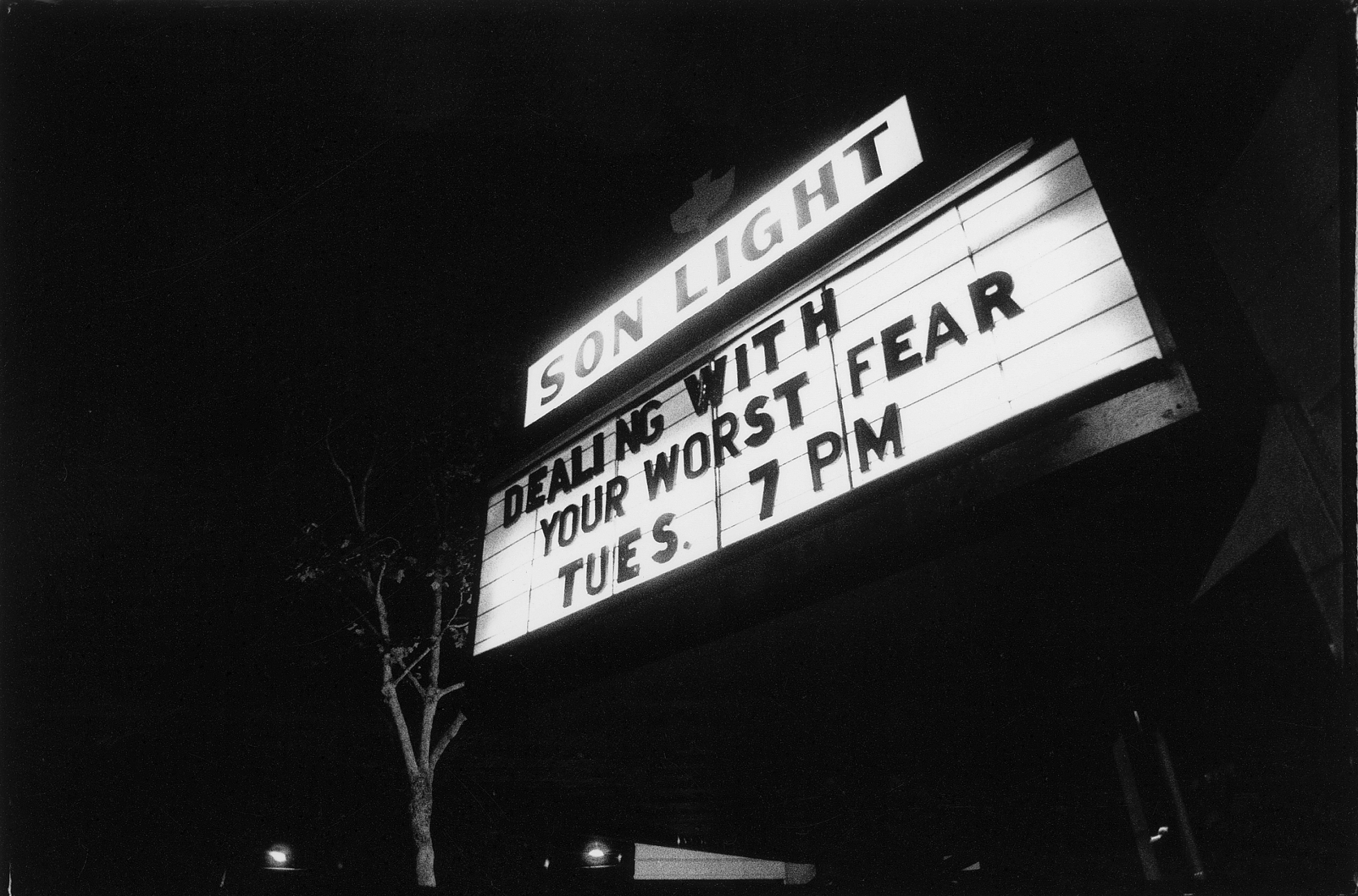

It didn’t end there. My ex-husband’s bankruptcy filing absolved him of his responsibility to pay me the money stipulated in our divorce agreement. Bill collectors started calling. The IRS came knocking: I had unknowingly signed fraudulent tax returns prepared by my husband. Thanks to compounded interest, the amount I owed the government was staggering. It took me years to pay it all off, and I teetered many times on the brink of despair. In the process, though, I learned that my worst fear could come true, and it wouldn’t kill me.

Fifteen years later I’ve lost my fear of economic insecurity. I recently gave up a six-figure salary to take a job I love for a fifth of my former income. I have become a more generous person. I trust that there will always be enough.

Mary K.

Fort Worth, Texas

The summer I was sixteen, I was living in a cheap Las Vegas motel with my mother. Our fortunes rose or fell daily with her luck at the dice and card tables. She’d often play all night and sleep until noon.

Still too young to enter a casino, I lived virtually without adult supervision. Las Vegas had yet to reinvent itself as a family-friendly destination, so there wasn’t much for teens to do. With only three movie theaters in town, I was always running out of films to watch. So I went to the public library, which had excellent air conditioning. (The unit in our motel room wheezed and splattered water on my books.) I got there each day when the doors opened, and I read historical fiction in the morning and science fiction in the afternoon. I’d eat lunch at a cheap burger joint or, if Mom had done well at the tables the night before, a casino coffee shop.

At night I’d swim in the motel pool or join the parade of other dice orphans drifting up and down Fremont Street, lingering by air-conditioned vestibules that separated the cool casinos from the blistering sidewalks. We didn’t often cluster in groups or interact. It was as if we didn’t want to call attention to our abandonment by acknowledging each other.

When I missed my mother, I sought out the ladies’-room attendants in the casinos, who were like a kindly sect of cloistered nuns. They let me curl up and read books on the rump-sprung couches or told me stories of their lives, which invariably had been full of tragedy and adventure. Once, a young woman fainted in a bathroom stall and had to be carried out on a stretcher. After the paramedics had left, an attendant whispered to me, “Honey, that happened because she was overfucked. We see them like that in here sometimes.” I nodded, staring with wonder. I hadn’t known it could be fatal.

Mischa Adams

Santa Cruz, California

Dad’s side of the family came to California in the thirties from Oklahoma with all their belongings packed in an old, beat-up car that broke down along the way. Dad’s treasured bike had to be sold for gas money. In school I learned about the Dust Bowl and the “Okies” who’d lost their farms and moved to California. I assumed this was what had happened to Dad’s family. About a week before Dad died, however, I learned that they’d left Oklahoma not because they’d lost the farm, but because Granddad had been run out of town for running illegal card games.

So that was where Dad had gotten his gambling addiction. He’d lost more than a few paychecks to card games and once had come home without the family car. Lenders sometimes came through our home to decide how much collateral our household goods were worth.

When my eldest son turned twenty-one, I sent him a poker set as a rite of passage. I’ve since learned that he’s discovered those same card houses where my father lost so much money. What was I thinking?

M.C.

Huntington Beach, California

In the 1970s, some friends and I took a day trip to the dog track. We supposedly had “inside information” on a race. It wasn’t even gambling; it was a “sure thing.” We came home with lighter wallets.

Thinking we might as well keep the money within the group when we gambled, from then on we decided to start a weekly poker game. We played every Friday night and into Saturday morning. The stakes were pennies, nickels, and dimes.

Time rolled on, and the weekly poker game evolved. One player died of cancer; two new players joined. We took road trips to Atlantic City, Biloxi, and Las Vegas. We held weekend poker tournaments in a cabin in the woods or a condo at the beach.

The phrase “friendly poker game” is an oxymoron, but our group has proven to be an exception. Over the years the other men have loaned me the cash to install a much-needed septic system, painted my house, and helped raise my sons. They have been with me through three open-heart surgeries, five amputations, and a mistaken terminal diagnosis. They have built wheelchair ramps inside and outside my home and come to my aid on a moment’s notice.

Playing poker with these men isn’t gambling; it’s a sure thing.

Michael W. Raymond

DeLand, Florida

My husband and I were on our way from the East Coast to California, where he planned to set up his medical practice. We stopped overnight in Las Vegas, and as I got into bed at the motel, he told me he wanted to go play twenty-one. He said he’d be gone only a short while. He came back at sunrise. (His excuse was that he couldn’t tell the time because casinos don’t have clocks. Or windows.)

Our new home was just four hours from Vegas, and we went back there frequently. My husband got better at twenty-one and usually paid for our weekends with his winnings. It was the same routine every visit: I’d go to bed, and he’d stay up to play “a few rounds.” He’d show up again at about six in the morning, apologizing that he’d lost track of time. It seemed out of character for my responsible husband to stay out all night and gamble rather than stay in bed with me, but it was only on these trips. I learned to live the life of a gambler’s wife: chatting with bartenders, spotting call girls, getting massages, and shopping.

Many years later, when the marriage ended, I learned that his chosen activity wasn’t gambling, but late-night encounters with other men.

Bree L.

San Francisco, California

I was in Las Vegas for the Mother’s Day protest at the nearby Nevada Test Site, where our country tests nuclear weapons in violation of international test-ban treaties, as well as a treaty with the local Shoshone Indians. I had come here several times before to protest, but this trip was different: I had recently become a foster parent and had promised myself I wouldn’t do anything that might get me arrested.

I’d planned to work in the kitchen, preparing food for hundreds of protesters. Unfortunately my period started as soon as I arrived, and Shoshone culture prohibits women from preparing food when they are menstruating. Because I was on their turf, and hoping to correct a wrong my government had done them, I honored their tradition.

I wandered aimlessly around the camp for a while. Then I decided to take a gamble: I went by myself down to the gated entrance of the test site, which was guarded by the army, law-enforcement officials, and the FBI. No other activists were there. I sat down on a nearby rock and wrote a letter to the guards, telling them about myself: I was new to parenting. I was from Montana. I liked to drink beer. I had a market garden where I grew lots of basil.

I wrote about the chaos there would be the next day, during the protest, with people getting arrested. I told them to remember that all the activists had stories like mine. I asked them to go easy on us, and keep in mind it was a sacrifice for many of us to come to Nevada to protest. In exchange for their reading my letter, I said, I’d obey the law: I wouldn’t get arrested. And on the solstice I’d drink a beer, eat some basil, and send them kind thoughts.

I approached the gate. A handful of guards swaggered over to me, adjusting their gun belts and their mirrored sunglasses. I offered them my letter. One asked, “Is it about our job?” I said no, it was about me. He took it.

The next day at the protest, the guards were dragging people out of the way. People barked orders on both sides. Protesters circled, danced, drummed, and chanted. I saw the guard who’d taken my letter. He was bending over a prone protester.

“Hey,” I yelled, “did you read my letter?”

He stopped and looked at me kindly, with the sort of human recognition I’d sought. “Are you Pam?” he yelled. “How’s the basil?”

Pam Gerwe

Whitefish, Montana

My husband and I moved to Las Vegas expecting to live lavishly on the money he earned using his gambling “skills.” After our savings ran out, he changed occupations and became my pimp.

It wasn’t the first time: two years earlier in San Francisco, he had attempted to share my body with the consuming male public, but his plans had been thwarted by a pimp who’d persuaded me, with cold blue steel against my head, to leave his turf.

This time I joined an escort service. When my workday ended at 3 A.M., my husband and I would go out on the town and lose most of the money I’d just earned. All I ever got out of it was a custom-designed yellow convertible, which he eventually sold.

My husband gambled with my life. So did I.

C.C.

Salt Lake City, Utah

After graduating from college, my friend and I left the United States and flew to New Zealand, having saved enough money for a few months abroad. To earn extra cash and stretch out our trip, we decided to work on New Zealand’s North Island picking apples. We’d heard that you could make good money there during harvest season. After a week of working outdoors in torrential rains, we discovered another way to make money: online poker.

The first thousand dollars we won was a thrill. That thousand quickly turned into two, then three. The more we made, the higher the stakes we played for; the higher the stakes, the more money we made. We bought plane tickets to Australia, and then to Singapore.

Eight months later, I was sitting in an Internet cafe in Bangkok, drinking and playing several two-thousand-dollar-buy-in games simultaneously. At five in the morning, tired, drunk, and unfocused, I lost it all — more than six thousand dollars.

Angry at myself for my lack of self-control, I stumbled back to the hotel, past prostitutes and rickshaw drivers offering me sex and drugs and good times. In the hotel room I took off my watch — an expensive present from a generous friend — and threw it against the wall over and over until it shattered. It was a savage impulse, as if destroying my most cherished possession would somehow release me from all this.

Ethan Earle

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

When I was ten, my friends and I went to summer day camp, where we learned arts and crafts and swam in an Olympic-size pool. Walking to and from camp, we’d kick cans, toss pebbles at unsuspecting motorists, and generally try to think of new mischief. One day my friend Mark produced a pair of dice he’d taken from a Monopoly game and announced, “Let’s gamble.”

We each had a few coins left over from our lunch money. Mark picked a number, and whoever rolled the closest to it won the pot. I was addicted immediately. We played dice every day, and I stole coins out of my dad’s change jar to support my habit.

My gambling addiction got progressively worse over the years. Once, I almost had my thumbs broken by mobsters when I couldn’t pay a thousand-dollar bet on a basketball game. I’ve ridden home penniless from Indian casinos. I’ve bet on everything from who can spit the farthest to who can sleep with a woman in the shortest amount of time after meeting her.

Now, thirty years after I learned to gamble while walking home from camp, I live in another camp: a prison camp. Presently I am wagering on baseball three times a week, down from seven. It’s a start.

Terrice L. Powell

Enfield, Connecticut