I GREW UP IN THE BRONX IN THE 1980s WITH AN IMAGINATION SO FAT AND FRENZIED, GOD COULD HAVE MADE TWO BOYS OUT OF ME — AND HERE IS WHAT I REMEMBER OF THAT LIFE.

My mind had a mind of its own, and over the top of the real world, my mind’s mind projected a world that to me was even more real. Creston Avenue — the street I lived on with my mother and my older sister, Asia — was two streets: one the way it actually was, and one the way it ought to be. A gushing fire hydrant drenching kids in the street became a small gargoyle shooting acid from its mouth to dissolve its enemies. I was sure at any moment the kids’ smiles would turn to cries of pain as they disintegrated into puddles of flesh, bone, and blood. At night I’d slip from my bottom bunk bed and stare out across the ignited borough. The cars I saw from my fifth-floor window were giant metal cockroaches with glowing eyes, and the gunshots I heard in the distance were fights between those mutant bugs. (Mommy tried to fool me once by telling me they were backfiring mufflers, but I knew better.) The real world itself was nothing more than a place my mind’s mind delivered me back to every now and again so that I could take baths, eat dinner, get my hair braided or picked, and go to bed. In this place I was Keemy; in the other world I was King.

My mind’s mind was relentless. Even my own mother became two people: my mother, a tall woman with big lips, a wide nose and forehead, and bulging eyes; and a being named Mommy, the throbbing source of heat, food, and affection. My mother had a nasty temper, but Mommy was wildly affectionate. When she was just a mother, I rarely noticed the jewelry that adorned her ears and wrists and fingers; as Mommy, her earlobes were forged from gold, the silver bracelets and rings born from bolts of lightning. She smelled constantly of perfume, breath mints, and lip balm, and had slender fingers, which she once told me would have been excellent for the piano, if only she had learned to play. I rarely saw my mother’s hair, because Mommy so often wore African head wraps — a different color each day — that I believed were her hair. From this being named Mommy, I first understood the notion of pretty.

Only Asia, who was two years older than I was, remained the same in both worlds: Just sister. Just girl. Hardly real to me at all.

THE apartment building on Creston was the first place I remember us living as a family. Before that Asia and I had spent a year living with a friend of my mother’s named Ms. Maye, a fierce old woman with dark skin and hair like wild electricity who called a boy’s dick a “stick” and a girl’s pussy a “purse.” She often whipped Asia for supposedly letting boys rub their sticks against her purse. I wasn’t partial to purses and paid no real attention to my own stick, but Ms. Maye punished me for not eating my vegetables. She refused to let me have any fried chicken until I’d finished every last bite of the slimy okra that she piled on my paper plate. Most nights I’d get through less than half of it before gagging and spitting up the mush onto the table. While I cried, Ms. Maye would stand with her arms folded and threaten to let me starve if I didn’t realize how important vegetables were and clean my plate.

“Just swallow it, Keem,” Asia said to me one night. “Don’t think about it. Just put it in your mouth and swallow quick.”

Ms. Maye held a plateful of fried chicken, still sizzling atop the wads of paper towels she used to soak up the excess oil. I longed for the deep-fried meat, the crunchy skin, the salty bone that I’d split open with my canines so I could suck out the marrow. The aroma was delicious, and it was torture. I managed to force a few more forkfuls of okra down, aided by the memory of what fried chicken tasted like. But after I was done, all I got were two runty legs that had barely any meat on them.

When Mommy showed up at the end of each month to pay Ms. Maye for keeping us, I’d tell her how the woman had made me eat nasty vegetables.

“Don’t you want to be strong like Popeye?” Mommy would ask.

Of course I did, I said, but Popeye ate spinach, not okra, which tasted like snot.

“How do you know what snot tastes like?” she asked.

I broke into tears, partly because of how I had suffered at the dinner table, but mostly because of the burgundy-plaid poncho Mommy was wearing, the sparkling earrings that hung from her lobes, fine as tinsel, and the glorious hair atop her head, which was vanilla-ice-cream white that day. The scent of her perfume stretched across the space between us, drawing me in. She looked and smelled the same as the last time I’d seen her. These visits hurt, because her presence meant that soon she would be gone for another four weeks. It was like having a mother and not having one. And so I cried.

“She be forcing him to eat it,” Asia snapped, wagging her finger in the air. “That ain’t right.”

“Oh, girl, stop being so damn dramatic,” Mommy said. “Ain’t nothing wrong with okra.”

The three of us were standing in the hallway of Ms. Maye’s apartment. On the wall next to the door hung a cluster of diamond-shaped mirrors. Mommy caught sight of herself in them and frowned. Her arms came out from beneath the poncho to unravel a section of her white hair, pull it tight, and then fasten it back. She did her lips with a tube of lip balm and gave each of her wrists a long inhale before turning on us like we’d just cursed her name: “I ain’t playing with either of you. You best behave yourselves. I mean it.”

Asia and I both knew the sudden anger in her voice was a ploy to distract us from the fact she was about to walk out the door and be gone for another month. I clung to her, my arms reaching inside the poncho. She struggled to free herself, telling me to hush up all that damn crying. Asia was crying too, but without much noise, her arms folded and her face creased with anger. Finally Mommy sighed, kissed me on top of the head, and told me that she’d see me real soon: “I promise, baby.” But I wouldn’t let go.

Then she said to Asia, “You ain’t gonna hug me?”

“How come you gotta leave us all the time?” Asia said.

“Don’t I always come back?”

“You know what I mean. Take us with you.”

“Girl, don’t make me out to be evil,” Mommy said. “I’ll see y’all real soon, and you know it.”

“You a liar.”

“Watch yourself now.”

While they argued, I pressed myself hard into Mommy’s body, the side of my face smashed against her stomach. Her promises slipped directly into my head while Asia’s pleas swept into my free ear, their voices slamming into one another inside me.

“Be strong for Mommy,” Mommy said to Asia, her tone low and tender now, the way it got when I was sick and she came toward me with a spoonful of cod-liver oil. “You know you have to take care of our little man. You know how he is. How he gets. I don’t have anybody but you to look after him, and you know that. Right?”

“Yes,” Asia said.

“Right?”

Asia said it again: “Yes.”

I had no idea they were talking about me; I was busy pulling on my mother’s hips, trying to drive my face and shoulders back into her belly so there would be no way she could leave without me. For all I cared, Asia could stay there with Ms. Maye’s mean old ass and the plates of okra and fried chicken.

“Let go, Keem,” Asia said, slipping her arm around me. “Let her go.”

Mommy unhooked my arms from her waist and helped Asia restrain me as I went wild, my eyes shut tight and arms flailing. Mommy was still close enough that I could smell her, and my feet brushed against her leg when I kicked, but the image of her was slowly disappearing from my head. I couldn’t go another month without seeing her, without any evidence of her I could rely on in my minds.

A short time after that, I took hold of a boy’s ear at school and tried to pull it off his head because he’d skipped in front of me in the line to the bathroom. Ms. Maye called Mommy and told her that she couldn’t take it anymore; it was time for her to come get her damn kids.

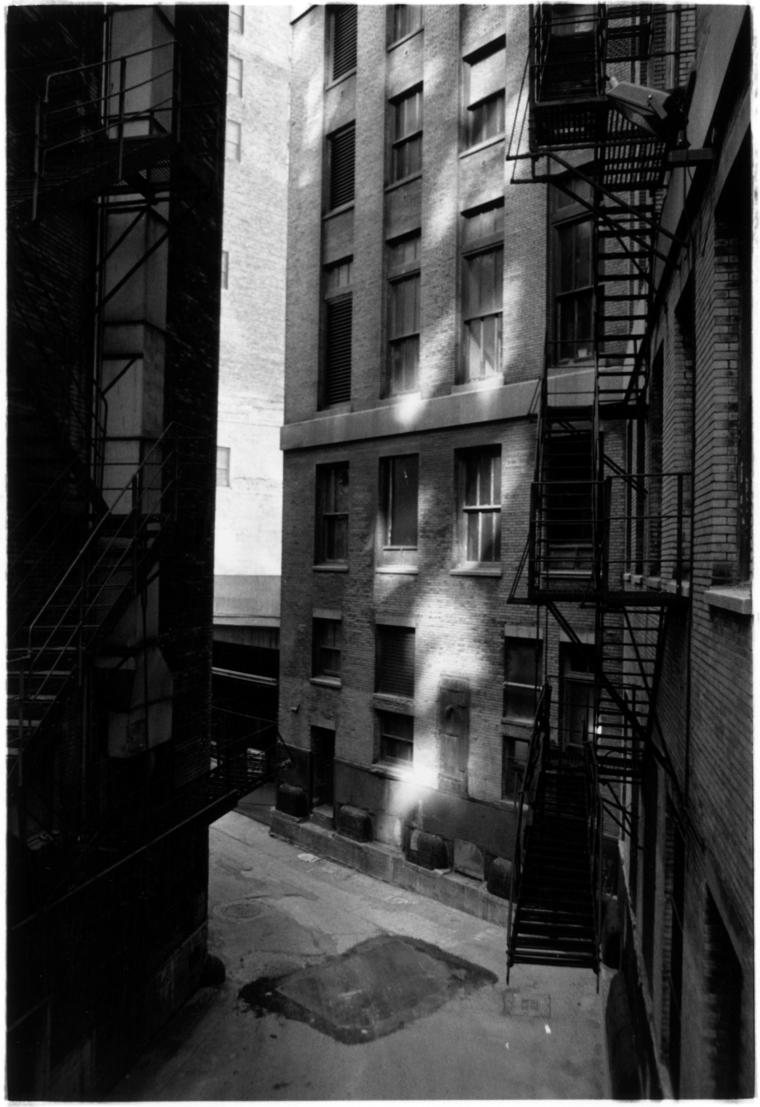

ASIA and I lived at Grandma’s place in Queensbridge for a while and with another of Mommy’s friends on Kingsbridge Road before Mommy found the apartment on Creston. I was seven, and if I hadn’t forgiven her for leaving us with Ms. Maye, it no longer mattered the day she brought us to see our new building. With a wave of her arm, as if snapping a sheet off a magnificent gift, she said, “Look, babies, at where we’ll be living!” I craned my neck to take in the gargantuan six-story tenement, thinking Mommy meant the whole fortress was ours. The building looked like it had been chiseled from a mountain, and the brown fire escapes were the rungs of a ladder that stretched to the sky. Our new home felt both still and alive, like a hibernating creature. As we walked toward the entrance, I dragged my hand along the gritty stucco side of the building as if stroking a sleeping dinosaur.

More disappointing than the discovery that we had only an apartment to ourselves on the fifth floor, or that I shared a bedroom with Asia, was that my palace overflowed with families — which my mother called “tenants.” No matter how loud I made gun-blast and fistfighting noises while playing with my action figures, there were always the louder sounds of the building: squealing cries of children (I couldn’t tell whether they were being tickled or beaten); the thumping beat of music vibrating up through the worn hardwood floors; doors being flung open and slammed. English and Spanish became one language to me when voices along the stairwell roared, Shut the fuck up! or, Cállate, cabrón! The constant noise of other lives made it difficult to sink deep into my imagination, so that the toys in my hands were only toys, and my fingers were nothing more than fingers, not an invisible force that made my action figures into living, breathing men.

Sometimes I’d press my palms over my ears, grit my teeth, and picture the whole place and everyone in it exploding into flames.

When the block didn’t vanish in a cloud of smoke and ash, but took deeper root in my skull, I’d lie down on my bed and close my eyes. In my mind’s mind I’d see myself walking out of my bedroom, down the hall, and through the front door, a laser rifle in my grip. I’d start on my floor, going door to door, kicking each one down, charging inside, and taking aim at the tenants’ stomachs and limbs and faces. None was spared. I wouldn’t return to my own apartment until everyone had been slain and the building was quiet. Then I’d walk past my mother cooking dinner in the kitchen, her face engulfed in the steam from a boiling pot of chicken and dumplings. I was an assassin returning home from a mission who neither cared about nor needed Mommy’s affection, but she always took me by the shoulders and hugged and kissed me anyway and said, Good job, baby. Mommy couldn’t think with all that noise!

I’d nod and shrug and tell her it was no big deal, then sling the laser rifle over my shoulder and head for my bedroom. From the doorway I’d stop and look at the boy lying on the bed with his eyes closed as he imagined me standing in the doorway watching him imagine me. I was both boys at once, until I’d unravel myself on the bed and open my eyes. The building sounds never fully disappeared, but thinking of myself as something more than I was had the power to muffle the obtrusive presence of neighbors’ lives.

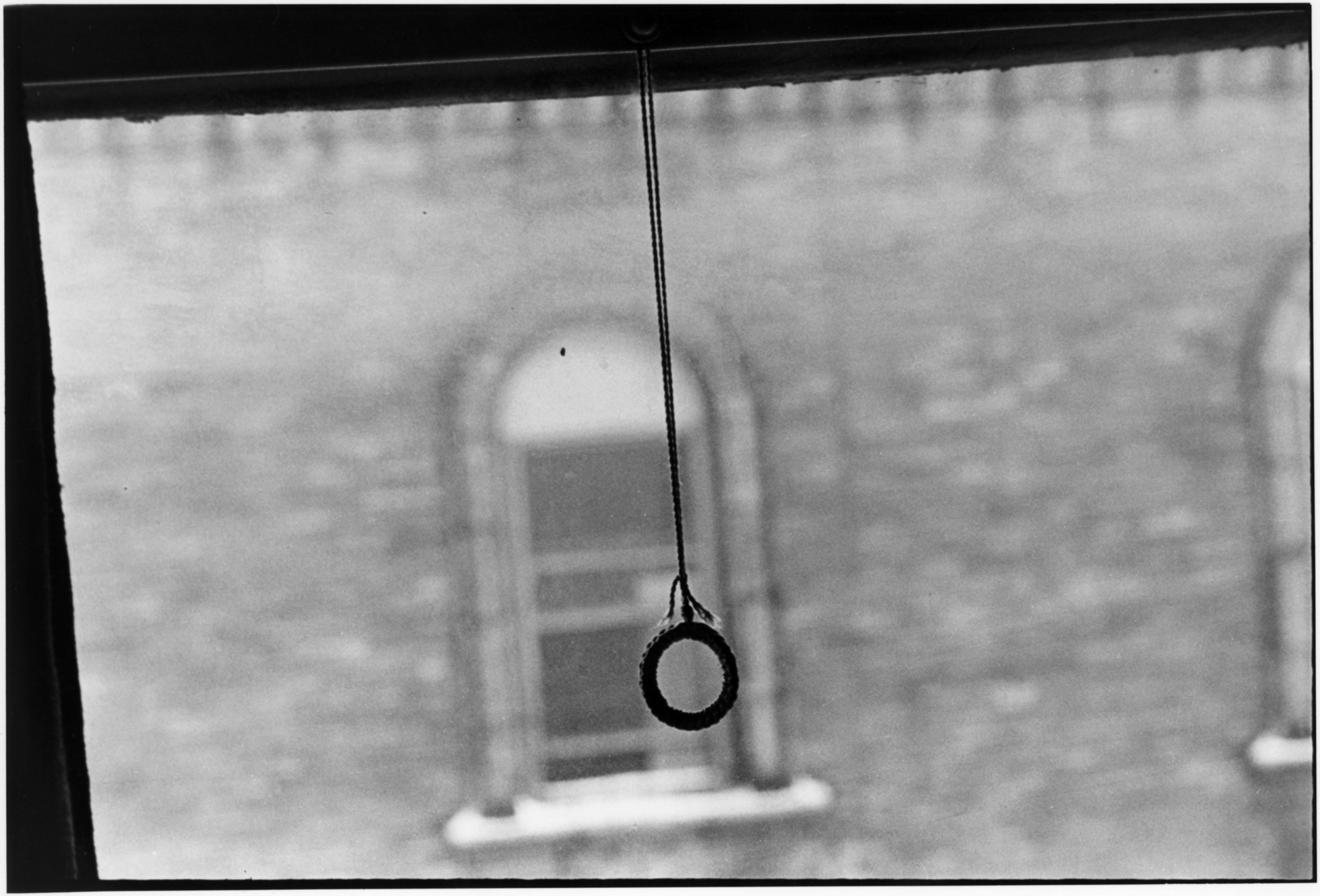

THE only friend I had was a boy named Julio in the building across the street. He lived on the fifth floor of his mansion, just like I did in mine, and our bedroom windows faced one another so that I could see him flying around his room, leaping back and forth from his sister’s bed to his with a red cape tied around his neck. Though I, too, dreamed of being able to fly, my main fantasy involved guns. Instead of wearing a cape, I wielded an M-16 and mowed down any invisible enemies who were either brave or stupid enough to show their faces, along with the cowards who hid under my bed and in the closet.

At the start of most summer days, Julio and I sat at our sills and shouted across the street to each other about the stories taking place in our heads. Eventually we led our mothers downstairs, arriving on our front stoops at the same time. I’d envision Julio and me leaping off our respective curbs and meeting above the tops of cars in a wondrous, midair, superhero embrace, but just as the idea took shape in my head, Mommy, sitting behind me on the stoop with her arms folded, would say, “I dare you.”

The threat whizzed past my ear like a warning shot and stopped me cold, though in my mind I propelled myself forward.

As for Julio, his mother hadn’t the same control over him. He’d be out of his building, down the steps, off the sidewalk, and into the street before his mommy could stop him. Without even checking for traffic, he’d race to my side, where we’d meet in an embrace. Our love for one another was bold and ritualistic, and our joy at being together was all that stopped Julio’s mommy from choking him to death for foolishly flying into the street against her instructions.

Julio and I would jump up and down, locked in each other’s arms, and then lift our shirts to reveal plastic pistols or laser guns tucked into our waistbands. Sometimes Julio was the bad guy, and I was the good guy, and it was my job to chase him up and down the sidewalk, firing shots or laser blasts while he ducked them all. At the end of the chase, he always took a shot in the gut or heart or back and fell flat to the concrete. Suddenly he became my friend again, my brother, a comrade whom some vile enemy had struck down. I’d fall to my knees at his side, watching as he faked being dead with his eyes open, something he’d seen in a movie. I’d pick up his gun, place it back in his palm, and wrap his finger around the trigger. “I have the power to bring you back to life!” I’d say. “Come alive again, Julio! Come alive!” When he didn’t, I knew it was because he liked the attention he got for being dead. So I’d add, “No, Julio! You cannot die. You are too strong to die!” Then I’d dance around him, waving my pistol at the gods.

After my performance he’d get up, and we’d spin each other around and howl like werewolves until we devised another scenario, which usually consisted of Julio shooting me dead and falling to his knees to bring me back to life. When it was time to go back inside, our mothers had to tear us apart, kicking and screaming, our hands curled into claws as we reached for one another.

THAT fall, on cold school mornings, my mother would iron a pair of my corduroys and a collared button-down as I stood shivering in the early dark blue of the living room in nothing but my underwear, afflicted with an unyielding erection. I either couldn’t see or didn’t notice the steaming iron, so I believed it was her own brown hand that ran back and forth over my clothes and brought heat into my world. The floor felt like a sheet of ice. I’d thrust a thumb into my mouth and with the other hand grip my penis and squeeze, making a game out of pushing the pain back from the tip, back into my thighs, where it seemed the hard-on had come from. After a few moments, though, my hand would weaken, and the pain would rush forward again, turning my stick back into stone.

Meanwhile my mind’s mind was working to give birth to visions of gunfights and explosions. One morning the pain was so intense that I was powerless to help a band of soldiers — my men! — as they moved aimlessly over a desolate battlefield, M-16s clutched in their hands. I could make only half-whimpering, half-choking noises, to which they responded with confused looks before slowly continuing along, guns pointing lazily toward the ground. Finally I cracked and started to whine. My men consoled me, and I apologized for not being able to conjure an enemy for them to fill full of bullets.

Mommy’s brown hand sighed and hissed as she pressed a pant leg, then a sleeve. “Shhh, baby,” she said. “I’ll be done real soon, OK?”

“Yargh.”

“If I rush what I’m doing, won’t you be colder than you are?”

“Yargh.”

“Because then your clothes won’t be warm, right?”

“Yargh.”

“So why is it good to have patience?”

Defeated by her superior logic, I said, “Because whining is for babies, and I ain’t no baby, and really warm clothes is better than a little warm clothes.”

“Are better.”

“Are better than a little warm clothes.”

She slipped the clothes off the ironing board and over my head and legs. I could feel my body grow warm and my dick relax. My men prepared to receive their first clear order of the morning: Them niggers are over the hill. Let’s kill their asses! And I was off again in my own world, the one where I knew every path, every sunset, every way an enemy could die.

Rather than force me out of this world, my mother was content to let me be while she got ready for her job at the post office downtown. She picked her battles, for she knew there was much more than M-16s and games with my penis that I was going to conjure, much more than she would be able to see or control. But when she needed my full attention, all she had to do was raise her voice, bend the two syllables of my name just so, and beckon me with a finger.

One afternoon Julio and I were locked in mock robotic battle on the sidewalk in front of the building when Mommy got that finger working. She stood above me on the stoop beside Julio’s mother, and both of them had their arms folded.

Mommy gave me a look, one eyebrow raised, that I knew meant for me to keep my little black ass right in front of this building until she got back. Then she said, “You understand what I’m saying, right?”

I nodded.

“We’re going upstairs to take care of some business,” she said. “I’ll be back in a little bit. Don’t. Move. From. That. Spot.”

Julio’s mother added something to him in Spanish, and he nodded his head quickly and said, “Sí.”

The moment our mothers’ legs had disappeared up the staircase, Julio and I resumed our mechanical battle. We played until the sun went down and the sky dimmed. By the time it truly got dark, Julio and I were spent and sat on the front stoop of my building, elbows on our knees, pistols dangling loosely from our forefingers. We hadn’t tamed the streets as planned. Cold and hunger had become more important than conquering villains. We were silent, separate boys then, wanting our mothers more than each other, looking over our shoulders every time there was a noise on the landing, hoping they’d finally descend the stairs to claim us from the street and carry us home as their sons.

But they didn’t.

With the last ounce of energy in us, we made our way into the building and took to fake-playing on the stairs, creeping higher up as our battle went on. Every time a door opened or someone shouted on the floors above us, we’d run back down to the lobby and pretend we’d been there all along. The sound of a bottle shattering, followed by a man yelling in Spanish, made Julio wince like he’d been hit in the stomach, and we ducked into a small alcove under the staircase. Shielded from view of the street, we listened to cars passing and to the wild voices of older boys and girls on the sidewalk and our own panicked breathing: mine a low hiss, Julio’s a harsh wheeze like a chain saw caught in his chest.

I don’t know which of us took out his dick first, but there we both were with them slipped through our zippers and pointing toward the ceiling. We hugged, pulling ourselves into one another like we’d done so many times before, only this time gripping each other’s hips, fingers hooked through the belt loops of our jeans. We slapped our pelvises together, our faces so close we smelled each other’s breath and saw into each other’s eyes in the dark. All the times we had taken turns falling to the ground and bringing each other back to life seemed to have led to this, and our thrashing hips settled into a rhythmic bumping, our breathing slow and sharp. I closed my eyes and felt like we were the same boy, that we had always been the same boy.

Then we stopped. There was nowhere else for the moment to go, and wanting our mothers took over everything once again.

Finally Julio’s mommy came downstairs with a soft, droopy look in her eyes. She placed a kiss on my forehead, then scooped Julio up and ordered me upstairs to eat. Her tone was feathery — the same as I knew Mommy’s would be when I got back to the apartment — and she smelled of that odor that reminded me of both food and candy, something meant to be licked or inhaled.

“Ahora. Go now,” Julio’s mommy said to me, but I didn’t move. I just watched her carry him away, his knees hitched against her hips, his arms slung around her neck. On these nights when our mothers had taken care of some business upstairs, they treated us like kings: we were allowed to talk back, skip baths, eat with our hands, and sit directly in front of the television. When it was time for bed, they’d get down on their knees next to us so we could say our prayers together and then kiss us on the lips good night. But I didn’t want any of that right then, and I didn’t want Julio to want any of it either. I sent a message to him with my mind — Run from her! — wishing for him to slip from his mother’s arms so we could parachute deep into the darkness of the alcove. Hunger pulled at my gut while I watched mother and son leave my building for theirs. Julio waved a weary goodbye to me, one that lasted down the stoop, across the street, up his own stoop, and into his building.

I took the stairs two at a time, feeling both mad that Mommy hadn’t come downstairs to get me and desirous of her touch after so much time spent away from her. Around the fourth floor I caught a whiff of a magic smell: incense, chicken and dumplings, and adobo seasoning. The scents became stronger with each stride closer to my floor, together forming an image of Mommy. The air was thick with her when I pushed through the front door and bolted down the hall into the kitchen.

Mommy stood at the stove with a pot lid in her hand. She looked up and saw me standing there, scowling, my arms tightly folded. Normally she would’ve snapped at me for not making any damn noise when I walked into a room and startling her, but now, her eyes red and her face damp, she said, “How’s my little boy doing?” Her voice was a melody, but I was still angry. On the way to the table I glanced in the sink and noticed Asia’s favorite sky blue plastic cup atop a dirty plate: Mommy had fed her first. I heard music from our bedroom down the hall and Asia singing along to a song.

“I’m thirsty,” I said, pouting, frustrated that my mother had chosen Asia over me. “Get me something to drink.”

“Who in God’s name you think you talking to, boy?”

But instead of smacking some sense into me, she retrieved a large cup from the dish rack and filled it full of red juice from a plastic jug on the kitchen table. She was still Mommy, but at the same time not. She piled spoonfuls of chicken and dumplings onto my plate, more than I’d be allowed on nights when her voice clicked like the second hand of a clock: Sit. Ass. Chair. Now. She set the steaming food in front of me and then held my face in her palms and kissed me right on the lips. I rubbed the back of my hand over my mouth as though her kiss disgusted me.

“Oh, stop,” she said. “Go wash your hands before you eat.”

“I already did,” I told her, though we both knew I hadn’t and was deliberately lying because I believed I could get away with anything at that moment.

Mommy looked at me quick, seriousness flashing in and out of her face, like she was trying to get mad but couldn’t help smiling. I didn’t want to push it. These moments of being treated like a king-son never lasted for more than one evening, and I was scared of what would happen the next day when she remembered how I’d behaved the night before. So I stomped — not too loudly — down the hall to the bathroom, washed my hands, and then stomped all the way back to the kitchen and dumped myself back into the chair, my arms folded even tighter across my chest. The plate of food still steamed with hotness, and Mommy stood there looking at me like she wanted to kiss me again, and suddenly she did — on the cheek this time, then on the temple — and I let my mood subside into hunger and affection.

“The food’s hot, baby. Don’t eat too fast, all right?”

I nodded and dug in. She disappeared for a while but soon returned to refill my glass and add to the mound of dumplings still on the plate.

“Good, good, good. Eat up, eat up.”

She was talking faster than before but still calm. My stomach was full, my lips were sticky with drink, and I didn’t think anything of her standing near the stove and saying, “You cold, baby? It’s so cold in here. I can’t believe how cold it is.”

I considered the kitchen’s temperature. It was cold, I guessed. Though the room pulsed with the heat of the stove, I could see how Mommy could be cold.

“I’m so cold, I’m so cold, I’m so cold. You need anything? You want some more?”

“No,” I said.

“You sure, you sure? You can have as much as you want.”

“No,” I said.

“What about pie? You like apple pie.”

It was my favorite. The pie was already on the counter, a knife already in her hand. I looked down at my half-full plate of food. “I haven’t finished.”

“It’s OK, you can put the pie on the plate next to the rest. It’s OK, I promise. It’s OK.”

Mommy held the knife tightly in one hand, and with her other she rubbed her arm furiously, more like she was scrubbing it than trying to stay warm. She stared at the pie with bulging eyes and shifted her weight back and forth, like she’d forgotten how to cut dessert and was unsure of what to do with the knife that she now held in both hands. “It’s so cold, it’s so cold, it’s so cold.” She made tiny, hesitant strokes in the air above the pie, then shook her head and said, “Uh-uh,” made a few more strokes, then said, “Uh-uh,” again. I was grateful she was taking so much time to cut me the perfect piece. She dipped the blade inside, then snatched it out quickly, unsatisfied, before plunging it in again. She did this over and over, her slices finally turning into small stabs. I imagined she was a sword fighter, and the dessert was her enemy, and silently I cheered Mommy on.

THE way Mommy was going crazy the next morning — yelling at us to get up and get a move on, that she wasn’t playing no damn games, and if we wanted our asses kicked, then we could go ahead and test her — I thought it must be the first day of school all over. I lay awake in bed until Asia slipped off the top bunk, snatched the covers off me, and in a sharp whisper said, “You better get up, boy, or you gonna get it!”

I gathered a crumpled pair of pants and a shirt from the closet, knowing I wasn’t moving fast enough and would get an ass whipping. But I was unable to shake the magnificent daydreams I’d been having before I got up, and there was nothing I could do about my mind and its mind. There never had been anything I could do, even with Mommy blowing through the house like a madwoman, clutching at her hair, which was green that day. I crept into the bathroom and closed the door, hoping Asia would get the brunt of Mommy’s anger, and when I emerged, I’d be the good child. Then I worried it’d be worse for me if Mommy had to come looking for me, and I hurried to wash my face and slipped my head beneath the running faucet to dampen my morning naps. To get ready faster, I got the idea to brush my hair and teeth at the same time. When my mother burst into the bathroom with the belt, I was about to rake my hair with the toothbrush and put the hairbrush into my mouth.

“You got one minute to get your ass out here and at that table,” she said. “One minute.”

Sixty seconds later I was at the table with bad breath and nappy hair, but Mommy didn’t seem to care. She stood with her back to us, her head down, her hands resting on the edge of the sink. “Foolish, foolish boys,” she said, and she covered her mouth with her hand. Then she said it again, through her fingers: “Foolish, foolish boys.” I wondered what boys she was talking about.

“Can I have some cereal?” I asked.

“Get it yourself,” my mother said.

The economy-sized box of Honey Nut Cheerios was too big for my hand, and I often dropped it, scattering the tiny o’s all over the table. Asia was already eating cereal, the spoon rising and falling slowly from the bowl to her mouth while she cautiously watched Mommy shake her head and move her hands all over her face. As I reached for the cereal box, Asia snatched it up and poured a pile of Cheerios in my bowl. I grabbed the milk carton before she could help me with that too, not wanting her to treat me like one of her dolls she carried around by the throat.

After pouring the milk, I played my usual game with the Cheerios, pretending that the o’s floating in the milk were miniature, faceless neighbors who believed I had come to rescue them from drowning by scooping them onto my spoon. Once they were safely in my stomach and the pool of milk was free of people, a cheering rose from my gut. Then I picked up the bowl and drank the remaining milk, sending a tidal wave of liquid down to drown them all for good. I wiped my mouth with the back of my shirt cuff and burped, then poured another bowl — by myself this time.

“If you put a drop of milk in it,” my mother said, “your ass is mine.”

“But I’m hungry,” I whined.

“Stop being greedy all the damn time.”

“But I’m hungry,” I told her again, remembering the night before, when I’d gotten away with so much, and all she’d done was give me a soft-stern look and feed me pie and plant wet kisses on my forehead that dried in the hot air of the kitchen. Now she shot me a glare.

“Go ahead,” she said, but when I reached for the milk, she added, “I dare you.”

After a moment of staring at me, she sat down with us at the table, plunged her face into her palms, and cried. “Fuck it,” she said. “Have as much as you want.”

Asia reached over, touched Mommy on the arm, and said, “What’s wrong? Please tell us what’s wrong.”

I was immediately jealous that I hadn’t asked the question, that my love for Honey Nut Cheerios had been more important than finding out what was wrong with my mommy. “Yeah, Mommy, what’s wrong?” I said, and Asia gave me a look.

“He cracked his head open,” Mommy said. “There’s blood all over the sidewalk.”

“Who did?” Asia asked.

She told us that the night before, after Julio’s mommy had tucked him in and his sister had fallen asleep, Julio had fastened a bath towel around his neck with a safety pin, opened his window, and jumped from his fifth-floor room to the sidewalk below.

My first thought was to be upset that I hadn’t had the courage to go through with the plan first. Whenever I’d tied a towel around my neck, I’d only run up and down the halls with my arms out in front of me. Though I knew boys couldn’t really fly, I also believed it was because they hadn’t tried the proper way. And now that Julio had done it — had tried to fly and hadn’t died, but only injured his head — I thought that I could succeed where he’d failed.

After breakfast Mommy led Asia and me downstairs and across Creston Avenue to the front of Julio’s building. I expected him and his mother to come out to greet us so we could talk about how brave her son was and marvel at his bandaged head, but they never came. Mommy just pointed to the dried blood on the concrete.

“This is what happens to little boys who don’t listen to their mommies,” she said, her eyes still wet but her face as hard as a brick.

Asia started to cry. I didn’t know why.

“What kind of cape Julio had on?” I asked Mommy, trying to figure out what I could do better than him when my time came at the windowsill.

The blow Mommy delivered to the side of my head — half on my cheek, half on my ear — rocked me to one side and rang in my skull. While I tried to understand why I’d been hit, my mind’s mind quickly went to work: it took the light that had flashed through my brain when she’d struck me and produced an explosion caused by a car that had gone over a cliff. While Mommy shook me back and forth by the collar — Asia sobbing in the background — and spat, “Boys! Can’t! Fly! Can you hear me, God damn it? Can you hear what the hell I’m saying?” my mind’s mind rewound the footage, and the sedan’s body sucked the rolling flames back into itself. The warped doors and blasted glass reattached themselves, and the car rose back toward the cliff’s edge, where it leveled off onto the ground, the split guardrail closing behind it like a pair of double doors. The car slid backward up the winding road to the top of the hill. Then the film rolled forward, and the car began to descend the hill, out of control, brakes shot, picking up speed and then bursting through the guardrail and soaring over the cliff as Mommy shook me and shouted, “Boys can’t fly!” The sedan tumbled through the air to the ground below, and right as Mommy slapped me again, the whole thing went boom!

With each blow she told me to wake the hell up, and when I finally opened my eyes, I couldn’t hear her voice any longer. Veins pushed from beneath the skin of her long, elegant, non-piano-playing fingers. Her earrings swung against her cheeks. Wisps of brown thread peeked from beneath her green cloth hair. At any moment I was sure Julio and his mommy would come downstairs and scold Mommy for handling so roughly a boy she loved, a boy she’d fed and bathed and warmed, all with the same hands she was using now.

But my friend and his mother never came down.

It was just the three of us — me, Mommy, and Asia — on the sidewalk on that cold morning as my mother spoke to me without a sound, her lips forming the words Can! You! Hear! Me! Can! You! Hear! Me! The car sped toward the cliff, smashed through the rail, fell, and exploded over and over again, going boom! boom! boom! with each of my mother’s blows to my head. Finally I shut my eyes against the blistering pain that filled my face and held on tight to the boy inside of me until it was all over.