ON the first Sunday of Lent 2012 Rabbi Michael Lerner delivered the guest sermon at St. Mark’s United Methodist Church in the San Francisco Bay Area. Dressed in a suit and the traditional Jewish prayer shawl and yarmulke, he spoke for half an hour without notes and challenged the congregation to apply the revolutionary teachings of Jesus and the Prophets to their own lives. While acknowledging that religions throughout history have often created division, enmity, and fear, he cited evidence of what he calls the “progressive tradition” in all the world’s faiths: the emphasis on showing compassion, easing suffering, and protecting the environment. He urged his listeners to oppose the Christian Right’s efforts to dominate the discussion about religious values and politics but cautioned against demonizing others. At a reception after the service he signed his latest book, Embracing Israel/Palestine: A Strategy to Heal and Transform the Middle East, a provocative vision of a path to reconciliation.

Born in 1943, Lerner grew up in an affluent home in Newark, New Jersey. His father was a judge, and his mother was a campaign chair to a U.S. senator. (When Lerner applied to college, President John F. Kennedy was among those who wrote letters of recommendation.) Before World War II his parents had been leaders in the Zionist movement, and Lerner grew up surrounded by socialist Israeli pioneers. He came to see conspicuous consumption and the Cold War as threats to the values of both American society and the Jewish community. When he discovered Abraham Joshua Heschel’s book God in Search of Man, he began his lifelong quest to bring mystical and meditative practices back into modern Judaism as part of the “Jewish Renewal” movement.

Lerner studied at Columbia University, lived on an Israeli kibbutz, and participated in the Free Speech Movement at the University of California at Berkeley. By the end of the sixties he was an assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Washington in Seattle and a leader in the antiwar movement. As one of the Seattle Seven he was arrested for alleged conspiracy to incite a riot and jailed for contempt of court. (The conspiracy charges were later dropped.)

In the eighties he worked as a clinical psychologist in the San Francisco Bay Area, having completed two PhDs: in philosophy at UC Berkeley and in clinical and social psychology at the Wright Institute. Concerned about the shift toward conservatism in the Jewish community, he founded the magazine Tikkun (Hebrew for “healing and transformation”) to give a voice to progressive Judaism and interfaith dialogue. He was ordained as a rabbi in 1995 and a year later founded Beyt Tikkun, a “movable synagogue” that welcomes members of all religions as well as atheists and agnostics (www.beyttikkun.org).

I first sought out Rabbi Lerner after attending an Orthodox synagogue for years. I’d been raised in a typical assimilated Jewish family: my parents sent me to Hebrew school and gave me a bar mitzvah but had discarded basic Jewish observances like Sabbath restrictions and keeping kosher. I wanted a Judaism connected to deep traditions, and the modern Orthodox Jewish community had given me that, but I’d become uncomfortable with the openly anti-Arab, homophobic, and racist rhetoric I heard from some congregants. Friendly conversations could turn into discussions of the “enemies of the Jews” who were always “ready to attack us,” and any criticism of the Israeli government was dismissed out of hand. Within the community there was great caring and kindness, but non-Jews were often seen as corrupt and dangerous.

Then I discovered Rabbi Lerner’s “Introductory Judaism” course, which he offered at his home in the Berkeley hills. About twenty people attended, many not Jewish. Over three days Rabbi Lerner gave us a fascinating and detailed history of Judaism, the development of Christianity and Islam, the history of the Jews in Europe and the U.S., and the current state of Jewish Renewal.

In 2005 Rabbi Lerner founded the Network of Spiritual Progressives, an interfaith social-justice organization, and he currently serves as its codirector, along with professor and civil-rights activist Cornel West and Catholic nun Joan Chittister.

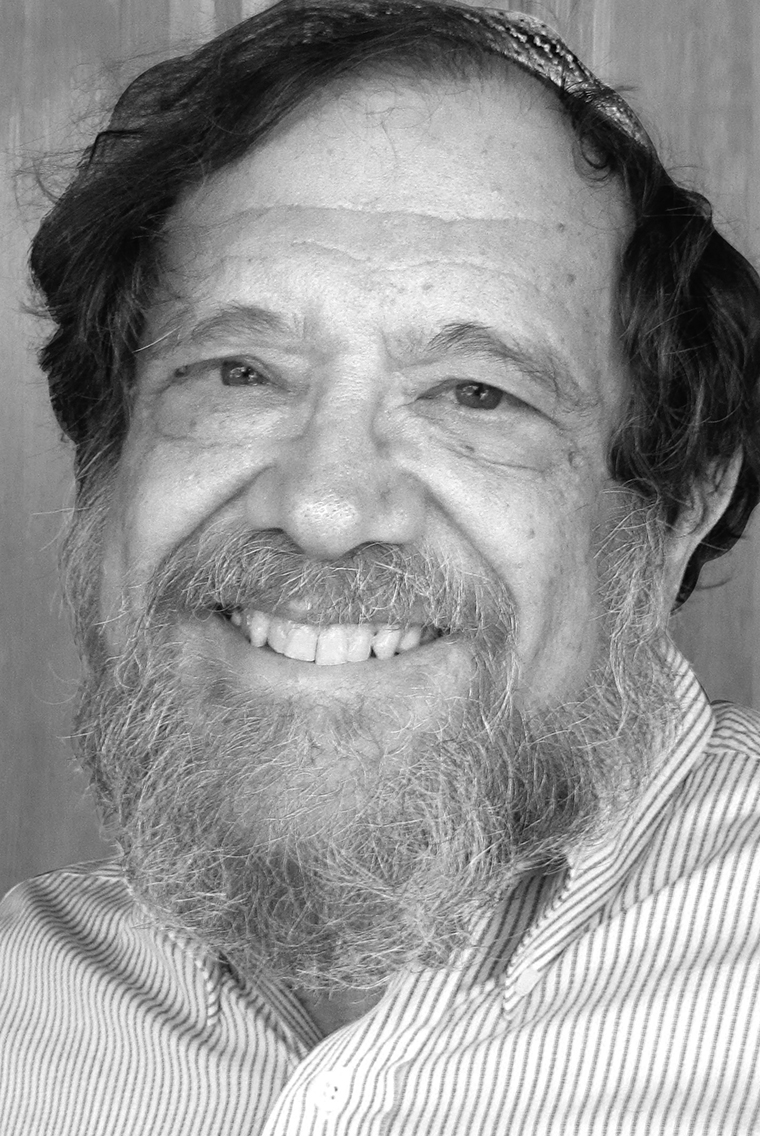

I interviewed Rabbi Lerner at his home in Berkeley. One of his favorite words is nuanced. In his writings and speeches he often constructs long, complex sentences full of clauses and parentheticals in order to include as much nuance as necessary. He dislikes sound bites, diatribes, and black-or-white thinking. In between passionate yet precise answers to questions, he grabbed a bite to eat with his wife, Deborah, who is also a rabbi, and played with the family dog. Although Lerner has had lung cancer for several years, he rarely slows down until exhaustion demands it. “Make sure you include my e-mail address,” he said (rabbilerner@tikkun.org). He loves to keep the conversation going.

MICHAEL LERNER

Leviton: You were last interviewed for The Sun in April 2004, just before George W. Bush’s reelection. Since then we’ve experienced the financial collapse, the rise of the Tea Party, the election of President Obama, the 2010 midterm elections — in which Republicans won a majority of seats in the House of Representatives — and the Occupy Wall Street movement. What’s your assessment of the health of our country at this point?

Lerner: I think we are less traumatized today than we were in 2004, because the effects of 9/11 have worn off for most Americans. Nevertheless, we are still seeing the struggle between two worldviews: One tells us we are thrown into this world alone and surrounded by hostile forces that seek to dominate and control us. Security comes only through dominating others first.

The other worldview is one of compassion. This view says we weren’t thrown into this life alone; we came into it through a mother who gave us our first experience of love, and she did it without expecting anything in return. Or maybe it was another caring person — a father, an uncle, or someone who adopted you. Someone provided that fundamental nurturance in the first few years of your life. This experience makes plausible to us a worldview that says security comes not through domination and control but through generosity, caring, and love. The religious and spiritual traditions of the human race are extensions of this worldview.

These two perspectives both exist in the minds of everyone, and which one is dominant at any given moment shapes how we see reality. The tragedy of 9/11 dramatically reinforced the idea that this is a scary world and there’s not much we can do except build up our armies and our homeland-security apparatus and protect ourselves in every possible way, sometimes by going out and killing those terrorists who want to hurt us. This is roughly analogous to saying that malaria is a really terrible disease, so we’re going to kill every mosquito on the planet. It would be far wiser to ask ourselves, “How do we dry up the swamps in which malaria breeds?” How do we dry up the swamps of hatred? The answer is not by bombing other countries but by approaching them with a spirit of generosity and caring.

We would have seen a very different outcome after 9/11 if we’d brought to it a worldview of love rather than fear. A different kind of president could have responded to the situation by focusing on the incredible generosity and goodness of thousands of Americans who risked (and in some cases lost) their lives in order to help victims of the attack, plus the outpouring of support and concern from almost every other nation in the world. The terrorists win, the president could have told us, when they undermine our trust in each other and in the goodness of most human beings on the planet. The way to defeat the terrorists, the president should have said, is to reject the worldview that the rest of the world is evil and out to get us.

Instead, by 2003 the U.S. was in a terrible war with Iraq, which led to the deaths of thousands of American soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis, not to mention the millions of Iraqis expelled from their homes — a terrible tragedy for both Iraq and the United States. Eventually a majority of the American people came to see that the war was wrong and that the worldview that had led us into it was problematic. So people responded with enthusiasm to the presidential campaign of Barack Obama, who made a point of saying that he had been against the war from the start. He led us to believe he would be a peace-oriented president and seemed to embody the more hopeful worldview.

Unfortunately once he got into office, he acted quite differently, and that has caused people to back away from hope and into skepticism and cynicism. By 2010 many of the people who’d voted for Obama were not even willing to vote again, because they felt so sick at heart at what they perceived to be his betrayal of campaign promises. At a deeper level many Americans felt humiliated at having opened themselves up to hope only to have the domination worldview take over again. The message is: “You people who think you can build a world on caring and kindness are going to be misled and shown to be fools.” Some Obama supporters may not vote in 2012 either, unless their fear of the Other — in this case the Republicans — becomes too great. Even then they’ll vote without the enthusiasm that shaped the 2008 election.

Leviton: What happened to Obama? Do you believe he was intentionally misleading voters with his message of hope, or was he transformed once he got into office?

Lerner: I think many of us were not listening carefully enough to what he was saying in the first place. We projected onto him a more progressive worldview than he actually held. On the other hand, he did foster that projection. He is a politician and a skilled manipulator. In 1996 Obama came to the conference Tikkun sponsored alongside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and he asked to speak. At first I didn’t know who he was — at that time he was running for the Illinois State Senate — but I was quickly convinced that he understood we were offering not just the same old liberal politics but a vision of a new bottom line of loving, caring, and generosity. He gave a great speech. He went on to win the state-senate race and in subsequent years showed up from time to time at Tikkun meeting groups, which eventually became the Network of Spiritual Progressives. In 2006 he and I met privately in his U.S. Senate office, and he told me he was reading Tikkun, that he loved my books, and that he identified with what I and Tikkun were saying. I believed him enough to write an endorsement of him in the San Francisco Chronicle during the 2008 primary.

So it was quite a shock to me to see his transformation. I don’t believe he was lying to us, but I do believe that when people get into certain positions of power, it changes their views. Let’s say you’re a worker, and suddenly you’re made president of the corporation. Unless you have a strong social movement pushing you in the direction of your ideals, you begin to look at the world from the point of view of a corporation president.

Obama needed money to run his campaign, and a lot of that funding came from Wall Street and the military-industrial complex. So immediately after the election many of his closest advisors were drawn from those worlds. They were “realists” who believed that if you want to change anything, you have to do it in a way that does not offend those with money and power. Capitalism was collapsing, and the only way to save it, they said, was to give huge amounts of money to the failing banks and investment companies.

I believe that pressure, along with daily reports from the CIA and the FBI and military intelligence about the situation in the rest of the world, made it hard for Obama to maintain his campaign positions. He needed people with different views around him. It was a huge mistake on his part not to appoint Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman and other progressive economists who could have advised him differently. Instead he listened to Clinton-era figures like Larry Summers, who had helped develop the policies that were now causing the crisis.

Leviton: So the realists are actually blind to what’s happening, and you, a utopian dreamer, have a more “realistic” grasp on the situation?

Lerner: Realism has been defined by the powerful and the media they control to mean any policy that does not significantly challenge the current distribution of power and wealth. So I say, “Don’t be realistic.” The God revealed to the Jewish people is a God that makes it possible to overcome systems of power and domination, starting with the liberation of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt. All people, who are created in God’s image, can aspire to transcend the constant voices from outside and from inside our own heads that insist we accommodate ourselves to the existing reality rather than change it.

Leviton: After 9/11 the media and the government called the attacks “senseless.” If someone suggested that the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were symbols of American power, that the targets made sense in that regard, the speaker was usually vilified. Most Americans couldn’t understand why anybody would hate us or want to attack us. Is it a persistent part of the American character to be blind to how we are perceived by others?

Lerner: I wouldn’t put it on “character.” I’d describe it as miseducation. I think most Americans have no idea what pain this country has caused abroad, particularly with its military and economic policies. Trade agreements that were developed during the Clinton administration under the name of “free trade” have made it possible for the U.S. to dump its surplus crops and products all over the world, where they sell at cheaper prices than local goods. The Third World agricultural economy has been virtually wiped out by this. Small farmers are going out of business and even starving to death, and when those of them from South and Central America seek to cross our borders and make a living here, they are portrayed not as victims of U.S. economic policies but as marauders coming to destroy our economy.

Only a small percentage of Third World citizens have benefited from these otherwise crippling economic policies. The vast majority, who were already poor, have gotten poorer.

Then you have the U.S. support of dictators. In the 1950s the CIA overthrew the democratically elected government of Mohammed Mosaddegh in Iran and imposed the shah, who ran a repressive regime for twenty-six years. And when the Iranian people rebelled against it in the 1970s, the U.S. took the shah’s side. As a result the extreme elements who won out hate the U.S.

Now our government supports the incredibly backward regime in Saudi Arabia. The Saudi leaders are treating their own people horrifically, and here we are, arming them to the teeth. We just made another nearly $30 billion arms sale to them: eighty-four new fighter jets.

Why are we totally insensitive to the needs of the vast majority of people on the planet? Is it because of American character? I say no. The British would do the same thing, and did when they were the largest colonial power. So would the French, the Dutch, the Turks. And if the Arab countries or the Chinese become the dominant world economic force in the future, they will do the same. I don’t believe it’s character. I believe it is the result of a global economic and political system that advances the interests of the few at the expense of the many. We need to democratize that global system rather than criticize our fellow Americans.

Leviton: Is better education a precondition for building a more caring global society?

Lerner: I think there’s no particular action that must be taken first. There never is. Whoever you are — whether you are a postal worker, autoworker, lawyer, doctor, high-tech expert — there are multiple ways you can advance the cause of love, kindness, and generosity.

In the sphere of education we are now facing an attack on public-sector teachers and professors, from grammar schools all the way to universities. Many will lose their jobs or find themselves teaching larger classes and working longer hours with more stress. These people have a responsibility to use their classrooms to teach about ethical and ecological sensitivity and awe and wonder at the grandeur of creation, and to help their students challenge the dominant ideology that says they live in a meritocracy in which those who succeed are those who deserve to “make it,” while the rest have less and are struggling because they are in some way deficient. Similarly, teachers should be helping their students learn how to challenge the myth that people are basically selfish. Classrooms are one of the only places, apart from the media, where people get exposed to different worldviews. Unfortunately most teachers will tell you they are supposed to teach their subjects, not values or caring for others and for the earth. They are now reaping the consequences of their moral obtuseness. But I don’t blame them entirely. They’ve been indoctrinated to think it’s inappropriate in public education to talk about anything that can’t be verified or measured. Because you can’t measure love, kindness, and generosity, they have no place. We can deal only with the facts, which are devoid of any spiritual or ethical content.

But this view, which says the only things that count are those that can be verified through observation and measurement, itself cannot be verified by empirical observation! In other words, it’s a religious view, the religion of capitalism, because money can always be counted. That view cannot, by its own criteria, defend itself. There are no empirical observations that support the idea that empirical observations are the only path to understanding what is real. These are religious beliefs, but they are so widespread that almost everyone sees them simply as “reality” or “common sense.” And so this religion gets taught in our schools and universities as though it were a value-free truth.

The Talmud says that you can start on a path of righteousness for unrighteous reasons, because once you’re on that path, you’ll be exposed to a different way of thinking and being, which can bring you to a higher level of consciousness.

Leviton: You said earlier that Americans’ level of fear has been declining since 9/11, but aren’t we seeing a reawakening of fear, whipped up by conservative candidates and media and exacerbated by worries about the economy?

Lerner: Yes, but let’s start with the fact that Obama won in 2008. And he won primarily with the votes of people who did not expect him to end up in the pocket of Wall Street, or to escalate the war in Afghanistan, or to create this new form of warfare using drone attacks. Obama won by the greatest margin since Reagan. So a significant portion of the population in 2008 was open to a different kind of caring, hopeful energy. But they soon became embarrassed and then humiliated by the cries of the skeptics and cynics. So they retreated.

Many people say, in Obama’s defense, that he has faced a determined opposition from congresspeople who have done everything possible to destroy or undermine his presidency. But I don’t fault Obama for not winning votes in Congress. What I fault him for is not using his bully pulpit to teach Americans why it is not OK for the rich to benefit at the expense of everyone else; why a single-payer plan is a far better healthcare system than we have now; how badly life on earth is threatened by production geared toward the competitive marketplace rather than toward the needs of planetary survival; why it is irrational to criminalize marijuana; why wars are not the way to achieve world peace. And if you think that’s utterly unrealistic, then he could at least have told us what he was up against — the forces pushing him toward war and the 1 percent’s domination of the rest of us — and also what he thought the country really needed. When he decided not to prosecute anyone for the war crimes under the Bush administration, he could have explained that, even though they were war criminals by any rational definition, he believed this country would be torn apart by such a trial. And when he authorized money to bail out corporations, he could have explained that we need a national bank, but the U.S. isn’t ready for that sort of transformation of our capitalist system. In other words, he could have spoken the truth. His failure to do that is what allowed so many people to think that nobody in Washington is telling us what’s really happening.

I don’t want to minimize the good that Obama has done — for example, in allowing young illegal immigrants to stay in this country or in banning healthcare plans from disallowing those with preexisting conditions. I certainly believe that our country will be better served by Obama winning the 2012 election than by Mitt Romney. But my fear is that Obama’s abandonment of a more visionary politics in the name of being “bipartisan” and “realistic” may actually have demoralized the people he most needed to energize for his reelection.

If we want to change anything, it’s critical to create organizations that will fight for a caring society. Unless we can refuse to be “realistic,” unless we can be visionary and even utopian, we are not going to change. Even if we do reelect Obama, we will not be able to pressure him to represent our highest ideals, and we will still have a Democratic president with a Republican worldview.

Leviton: The Occupy Wall Street movement didn’t wait for the national government to lead. It developed its own rhetoric and actions. Were you surprised by the Occupy movement?

Lerner: I was delighted. Before it started, I was surrounded by people who said I was too idealistic, that nothing could really change. That was common sense in the summer of 2011. Then a group of people in New York City stood up to reject the system and fight for the interests of the 99 percent. The New York Times did a poll in December 2011 and found that 27 percent of people supported the goals of the Tea Party movement, while 54 percent supported the Occupy movement. If anybody had told you in August of that year that 54 percent of the people would support the goals of the Occupy movement, you’d probably have accused them of being unrealistic.

The people who preach that “politics is the art of the possible” continually forget that we don’t know what’s possible; we find out by struggling for what’s desirable. Instead of listening to those who tell you to pick goals that can be achieved in the current political landscape, I say pick goals that will create the kind of world you want.

Leviton: You were involved with Occupy Oakland and were disappointed.

Lerner: First of all, the Occupy movement in the Bay Area has given me many wonderful, hopeful experiences. I don’t want to put down Occupy Oakland or deny its achievements. The day of the general strike in November 2011 was incredible. Tens of thousands of people, instead of going to work, came to a rally in front of city hall and tangibly affirmed a very different worldview there. It reminded me of some of the best moments of the 1960s.

Similarly, the march to shut down the port, which mostly serves the interests of corporate America, was a beautiful moment. There was, however, a small group of self-described anarchists who, at the end of that day, destroyed private property and provoked the police in ways that led to violence. Afterward some in the Occupy Oakland movement tried to defend those actions. They did not want to commit to nonviolence and supported a “diversity of tactics.” They essentially said that those who believed in violence were welcome in the movement.

This put in danger a lot of people who thought they were coming to participate in nonviolent demonstrations. Suddenly the police were attacking them with tear gas and batons. It also made it possible for the 1 percent and the media, including the San Francisco Chronicle, to portray the whole movement as violent and avoid the topic of economic injustice. So I thought it was a terrible mistake. I don’t want to give a free ride to the police, who were unnecessarily brutal and acted in ways that would have outraged anyone, but we shouldn’t have responded to their bait with more violence.

I was part of a group of clergy who had come together to support Occupy Oakland, and I proposed that the group pass a resolution calling on the Oakland demonstrators to embrace nonviolence officially and tell those who did not that they were not welcome in the movement. And I lost the vote within the clergy group! Many of those clergy said they wanted to be nonviolent themselves, but who were we to tell these demonstrators how to act? After all, we didn’t sleep outside every night, and we were older than they were and had had different life experiences. Some of the black clergy voted with me, saying the reason there weren’t more black protesters was that they feared police violence; they’d had enough of that in their own communities. But most of the clergy preferred to win the favor of their fellow demonstrators rather than the favor of the majority of people in the Bay Area. That was extremely disappointing to me. I still belong to a Jewish contingent of the movement, but we’ve changed our name to Occupy Bay Area to avoid being associated with the violence at Occupy Oakland demonstrations.

I had a similar experience in the early 1970s as a leader in the antiwar movement. I was part of the Seattle Liberation Front. At a demonstration I’d helped organize, the police attacked demonstrators indiscriminately, and there were rocks and paint thrown at the courthouse. Afterward I gave a statement to the press saying I was deeply sorry and regretted the violence that had taken place.

At the next meeting of our core activists, some guy with long hair and a fringed jacket got up and asked who’d given me the right to denounce the violence. I had no business speaking for them: “We have to fight back against the police and this racist and imperialist system!” Many people cheered him and booed me. Six months later that same man testified against us. He was an undercover police agent. It turned out that undercover officers had brought the rocks that had been thrown at the courthouse, and the FBI had paid for the paint. So I am positive that some of the people provoking violence in the Occupy movement are also undercover agents who want to discredit us.

Leviton: You’ve written that the Left views religion as “either intellectual retardation or psychological handicap.”

Lerner: I call it “religiophobia.” It’s a prejudice on the same level as homophobia, sexism, or racism. As in every form of prejudice, there’s some truth in it, though its overall conclusion is wrong. Many of the people who are religiophobic came out of religious communities that were oppressive, sexist, racist, homophobic, and xenophobic. They generalized that experience to all religions without ever discovering that there’s another tradition inside each religion that is oriented toward peace and social justice. I don’t want to dismiss their anger. Those atheists, agnostics, or secular humanists who feel anger at religion often have a valid foundation for it. What’s invalid is to ascribe it to all religious people.

Those of us who have a spiritual dimension to our consciousness have to make public our progressive political vision and challenge religiophobia just as we’ve challenged racism, sexism, and homophobia. We have to help the nonreligious understand that they cannot dismiss all religious people as having a lower level of intellectual development. Many of us who believe in God do not do so as a way of escaping the complexities of reality. Rather, we understand God as the power for healing in the universe, the force that makes possible the transformation of What Is into What Ought to Be.

Leviton: You’ve been under treatment for lung cancer. How has your illness changed your life and outlook?

Lerner: I’ve never smoked, but my surgeon told me that the oil refineries near my childhood home in Newark, New Jersey, may have contributed to my illness, along with the oil refineries that pollute the air in the Bay Area, where I live now. I’ve always fought for environmental causes to help my grandchildren survive, but now it is an even more personal issue for me.

Leviton: You believe nationalism has been disastrous for the environment.

Lerner: Yes, I do. In order for us to save the planet, the world’s people — and foremost the American people — must come to understand that our individual well-being depends on the well-being of everyone else. We won’t prevent environmental disaster by preaching to other countries that they should change, because we created most of the environmental problems in the Western world. And Third World countries will not act to protect the environment when their citizens are starving to death. This is why I argue for a strategy of generosity rather than domination. At the website of the Network of Spiritual Progressives (www.spiritualprogressives.org) you’ll find a detailed plan for how to end global poverty, homelessness, inadequate housing, and insufficient healthcare. We call it the “Global Marshall Plan.” As long as people in the Third World are faced with the choice between fighting global warming and cutting down trees so they can cultivate the soil and feed their children, they are going to cut down the trees. They will choose short-term survival even if it means long-term destruction.

The Global Marshall Plan would dedicate 1 or 2 percent of our gross domestic product for the next twenty years to repairing the damage done by the past 150 years of irresponsible industrialization throughout the world. We must raise the living standard of the world’s poor to a reasonably comfortable level, or we will not be able to get the necessary agreements among nations to save this planet.

The Global Marshall Plan also deals with immigration. People are coming to the U.S. because they can’t make a living where they are. So we need to change the trade agreements to benefit the Third World poor. And we have to approach this task with a spirit of generosity and caring, because if it’s perceived as just another attempt on our part to get more power in the world, it won’t work.

Leviton: If you try to convince Americans to eradicate poverty around the world because it’s in our own best interest, doesn’t that play into the same old “what do we get out of it” attitude?

Lerner: It’s OK if people want to support the Global Marshall Plan for selfish reasons. The Talmud says that you can start on a path of righteousness for unrighteous reasons, because once you’re on that path, you’ll be exposed to a different way of thinking and being, which can bring you to a higher level of consciousness.

Leviton: You can “act as if.”

Lerner: Exactly. There’s a command in our tradition called tzedakah (charity). It says, “We don’t care what’s in your heart; do acts of righteousness and generosity anyhow.” It doesn’t matter if you take care of the poor because you want to be recognized in the community or you want your name on a plaque or to have a building named after you; it’s still counted as a mitzvah, a good thing. We’re not examining motives; we want action. But as you’ll see from the full version of the Global Marshall Plan on the website, to really make it work, people must eventually act out of generosity and caring. And anyone who’s an official working on this program has to be coming to it from that perspective, not from self-interest.

Vayikra [Leviticus], chapter 26, says clearly that if you don’t create a world based on loving your neighbor, loving the stranger, and pursuing justice and peace, the world won’t work. There will be an environmental crisis: the rain won’t fall, the sun won’t shine, the earth won’t yield produce, and humans and animals will be in great trouble. When I was a kid, this was a part of Judaism I couldn’t buy. I thought it was total fantasy, because that’s not how the world works. But as I’ve grown up and learned about the environment, I’ve realized that it does work that way. Built into the structure of the universe is the necessity of caring for each other and treating each other with kindness and generosity. In the final analysis, self-interest and serving God go hand in hand.

Leviton: And you see this principle in action in Israel and Palestine as well?

Lerner: There’s no command more frequently repeated in the Torah than “Do not oppress the stranger when he comes into your land; remember, you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” If Israel were the Jewish state it claims to be, that would be its core value.

Leviton: Sigmund Freud identified the “repetition compulsion” as a tendency for trauma victims to re-create the traumatic event over and over. Do you see this at work in the twenty-first-century Jewish psyche?

Lerner: The tendency to pass on pain from generation to generation is common to all peoples on the planet. But Jews have been one of the most oppressed minorities of the past two thousand years, and that trauma has created a fearfulness of the Other that has been passed on from generation to generation. That fear escalated into a massive trauma in the years 1938 through 1945, when one out of every three Jews alive was murdered in the Holocaust. To make matters worse, the nations of the world, including the U.S., refused to accept Jewish refugees seeking safe haven from the Nazis. This massive trauma has never healed, and it comes on top of two thousand years of fear that at any moment Christians would turn on us and kill us, as they frequently have done historically. And these experiences greatly intensify the tendency of the Jewish world to pass on its pain — both to our own descendants and to other peoples, particularly the Palestinians.

As I explain in Embracing Israel/Palestine, this trauma makes it impossible for most Jews to respond to challenges, particularly from the Palestinian people, in ways that are rational and consistent with the best Jewish ethical tradition.

Leviton: You’ve said that Jews did not come to the Middle East to oppress Palestinians, and Palestinians did not resist the creation of Israel out of hatred of Jews. How do you understand the encounter of these two peoples?

Lerner: I see it as a tragic misunderstanding caused by the historical experiences of each side. On the one hand, Arabs who developed Palestinian nationalism had the cultural memory of the Crusades, when large numbers of Westerners came to the Middle East to loot and rape and murder and stayed for hundreds of years. Arabs saw the Jews as similar invaders. Then you’ve got the more recent history of colonialism at the end of the nineteenth century, when the Western world came to the Middle East and Africa and Asia, dominating the peoples there and fighting among themselves about who would have control over which countries. These conditions led to the First World War, after which the victors divided up the Middle East, creating the states of Iraq, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. So Arabs saw Jews arriving in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as an extension of colonialism.

The Jews, however, were leaving Europe and Russia primarily due to the rise of anti-Semitism and reactionary forms of nationalism, which always find some Other to blame for society’s problems. Traditionally in Europe that Other was the Jews. Most Jewish refugees did not go to the Middle East; they went to the United States, Eastern Europe, England, South Africa, and South America, trying to run away from a long history of Christian oppression. Those Jews who went to the Middle East were greeted with hostility and anger by Arabs who got most of their information from the mosques, which were controlled by owners who lived outside of Palestine and feared Jewish settlers would bring capitalist values into their feudal world — or, worse, socialist values! So the mosque owners did everything they could to convince Arabs that these Jews were coming to expropriate their land and throw them out.

The Jews who immigrated to what later became Palestine found themselves the object of hatred again and decided they needed a homeland for themselves, maybe even a state, because wherever they went, the non-Jews hated them. They were surprised to be thought of as colonialists. They were running from the colonial powers of Russia, Germany, France, and England, which had oppressed them for 1,500 years.

So each side saw the other as fundamentally misguided and evil, because they could not recognize each other’s histories. And there was no serious effort on the part of either Palestinians or Jews to reach out to the other side and explain who they were and what their goals were. Instead there was violence, which ended up validating the most extreme right-wing or ultranationalist voices in each community. Eventually the socialists and internationalists in the Zionist movement became subordinated to the nationalist view, because the Arabs’ actions made it seem as if there were no way for the two sides to live in peace. And the Arabs and Palestinians heard Jewish talk of expulsion, which validated what they’d been told at the mosques.

The Jews went on to build the Histadrut, the most progressive labor union that had ever existed up to that point, but it was for Jews only. And the Histadrut not only functioned as a labor union; it appealed to Jews in the rest of the world to raise capital to build a Jewish state in Palestine. By the 1920s Jews all over the world were experiencing a resurgence of anti-Semitism, and they sent money. The Palestinians saw these institutions being built for Jews only and called it discrimination, but the Jews had never been allowed to own land or join professional guilds. From the Jewish viewpoint, this was affirmative action, to try to protect themselves as a minority. From the viewpoint of the Arabs, Jews were excluding them and collecting money from other Jews around the world, so it was the “international Jewish conspiracy” they’d heard about in the mosques.

Just as my love for the U.S. often manifests itself in a willingness to challenge the . . . ultranationalist concepts that shape American policies, so my love for Israel has manifested in my vocal criticism of Israeli policies that defy the tradition of Jewish ethics and Torah commands — particularly “thou shalt love the stranger.”

Leviton: Right now it’s more accurate to look at Israel as a sometime proxy for imperial powers.

Lerner: Yes, but it wasn’t then. At its inception Zionism was a legitimate national liberation movement. But because of poor choices it has become more dependent on imperial powers and more of a representative of them. But that was not the essence of Zionism at its beginning.

Leviton: Many left-wing groups insist that Israel today is an “apartheid state.” Do you agree?

Lerner: There are two Israels. The Israel within the pre-1967 borders — what is typically called the “Green Line” — is the democratic Israel that respects human rights. Like the U.S. it has its pockets of discrimination: against Arab Israelis, Arab Jews, African Jews, and the hundreds of thousands of Asians, Africans, and Europeans who have been recruited to fill the jobs that used to be done by Palestinians from Gaza or the West Bank. But none of the discrimination in Israel is built into the actual laws. In the democratic Israel, Palestinians are legally able to vote in elections and form Palestinian political parties. They have representation in the Israeli legislature. They attend Israeli universities and share the same beaches and theaters and public spaces as Jews. So in no way can the democratic Israel be considered an apartheid state.

In the West Bank, on the other hand, Palestinians live under conditions of extreme repression and fundamental legal inequality with the Jewish settlers there, many of whose settlements have been constructed on land that Palestinians contend was seized illegally either by the settlers or by the State of Israel. Under the pretense of providing “protection” for the settlers, the Israeli occupying forces have created a regime in which Palestinians are not allowed to drive on certain roads; are restricted in their movement from city to city within the West Bank; daily face humiliating body searches and hours-long waits at Israeli Defense Forces [IDF] checkpoints; are not given protection from the hostile and sometimes violent settlers; are subject to arbitrary arrest and imprisonment without trial for months on end; and in general are denied the human rights that their fellow Arabs living inside Israel’s 1967 borders continue to exercise.

This situation is in many ways far worse than apartheid was in South Africa. But it is not strictly analogous to apartheid, which was a system based on race. The oppression in the Israeli Occupation comes from an unresolved national struggle between two peoples, not racial discrimination. So, for example, Palestinian citizens of Israel who visit the West Bank receive the same basic rights and protections as other Israelis and Jewish West Bank settlers. It seems a huge mistake for the Left to describe this situation as “apartheid,” because that allows supporters of the Occupation to show how false that claim is. There are so many other ways of describing the Occupation to highlight its venality and oppressiveness without handing ammunition to the Right. I oppose boycotts, divestment, and sanctions against the State of Israel, but I support much more narrowly focused actions against products made in West Bank settlements and against global corporations that invest in West Bank settlement–related projects, or that build products specifically designed for the needs of the West Bank settlers.

Leviton: You believe Judaism itself is at risk from Israeli policies. How can the religion be threatened by politics?

Lerner: The danger is that Judaism’s primary representatives — its rabbis, teachers, and synagogues — have sought to integrate into Judaism a set of political values and attachments to Israel that have polluted the core of the teachings. For example, a prayer for the welfare of the State of Israel and another for the “victory” of the IDF are now standard in most Orthodox synagogues around the world. All branches of Judaism, with the exception of the Jewish Renewal movement, teach that support for Israel is an intrinsic part of Judaism.

Now, I support Israel too. But just as my love for the U.S. often manifests itself in a willingness to challenge the racist, materialist, capitalist, militaristic, and ultranationalist concepts that shape American policies, so my love for Israel has manifested in my vocal criticism of Israeli policies that defy the tradition of Jewish ethics and Torah commands — particularly “Thou shalt love the stranger.”

Today most younger Jews are taught that they are “self-hating Jews” or violators of Judaism if they publicly disagree with the policies of the State of Israel. This practice not only drives many young Jews away from Judaism; it puts life in Jewish religious institutions at sharp variance with the Judaism of all past generations, a faith that was self-critical, that valued differences of opinion about matters of Jewish law, and that honored the Prophets’ clear message: that those who do not care for the poor and the oppressed are defiling God’s name. That message, though ceremoniously repeated in our synagogues, is systematically ignored by large sections of the synagogue-going community when it comes to the Palestinian people; or to undocumented immigrants; or to the 12 million children under the age of five who, according to UN statistics, die each year around the globe for lack of adequate food and healthcare, a direct product of the system of global selfishness we call “capitalism.” Moral insensitivity is a prerequisite for giving blind support to Israel’s oppressive policies, and increasingly it carries over to Jewish responses to the suffering of others.

On the other hand, the pre-Zionist Judaism that insisted on Jewish identification with the powerless continues to be a part of the collective Jewish unconscious, reinforced by those prophetic texts that are read in synagogues every Yom Kippur. These traditions lead many American Jews to vote consistently against their own economic interests and in some way or other promise to embody social justice, peace, and equality in the policies they pursue. So while the cheerleading for Israel has the potential to further erode the loving and generous aspects of Judaism, it has not yet been fully successful in doing so.

Leviton: In Embracing Israel/Palestine you identify the punishment of all Palestinians for the actions of a few as a major flaw in Israeli policy. You say it reinforces the view that the Palestinian people as a whole cannot be trusted. How should Israel deal with terrorist attacks?

Lerner: The problem of terror is one that also faces the Palestinian people, in the form of Israeli settlers and assassinations of Palestinians who are suspected of being terrorists but are never given a fair trial.

As to how Israel should address its own terrorist problems: First, Israel should end the Occupation of the West Bank and Gaza as part of a comprehensive peace treaty (plausible terms for which I lay out in my books). After that, there will still be acts of terror by both Palestinian and Israeli extremists who seek to rekindle the struggle. These should be dealt with the way all societies deal with homicidal maniacs: as a law-enforcement problem, not as a war of nation against nation.

Leviton: Do Jews and Palestinians really need separate countries of their own? Should all ethnic groups — the Kurds, the Hutus, the Uighurs, the Tibetans — have their own lands?

Lerner: Any ethnic group that has a historically proven record of victimization by a majority culture and faces demonstrable acts of violence against their persons or their institutions should have the right to national self-determination and some land that they can call their own and protect from hostile forces. I do believe, however, that in the long run humanity needs to reject all forms of ultranationalism and unite to address the real problem facing the entire human race: the environmental crisis. We will need to transcend national boundaries so that we can reconfigure global politics along environmental districts, which may encompass many nations that were previously fighting each other or were indifferent to each other’s well-being.

I believe this can be achieved only when we stop looking at nature in narrow, utilitarian terms. We must no longer see it just as a “resource” and instead give equal priority to experiencing awe at the grandeur and mystery of the universe. That attitude — mixed with the Jewish commands to love the stranger, to pursue peace and justice, and to act with humility and generosity toward others — will open us to the consciousness necessary to save our planet and the human race. And I hope to see Israel and Palestine both in the vanguard of nations that reconfigure themselves as part of a global environmental unity.

I am pro-Israel and pro-Palestine both. I would argue that you cannot be pro-Israel without being pro-Palestine. Israel’s fate is intrinsically tied to the fate of Palestine, and vice versa.

Leviton: That seems a tall order. Most peace treaties come when one combatant wins — or, in cases like South Africa and Ireland, when a solution is found. But what’s needed in the Middle East is on a greater scale.

Lerner: Yes, because the history of trauma is so much deeper there. The Irish people never faced full-scale genocide. Even when English policies were effectively genocidal, as in the 1800s during the potato famine, the goal of England was never to kill every living Irishman. The Jews experienced that when Hitler attempted to wipe us out completely, and not in the Middle Ages but in the 1940s, while I was alive. And you didn’t have to live through it to be traumatized by it, because the trauma that experience generated is passed on from generation to generation.

Similarly right now you’ve got millions of Palestinians living in horrific conditions throughout the Arab world, oppressed not just by the Jews who created the nakba, or “catastrophe” — which is what the Palestinians call the events of 1948, when the creation of Israel was accompanied by the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians — but by their fellow Arabs, as well.

So you have deep crises for both Jews and Palestinians, and they won’t be overcome by one side winning, because neither side has the capacity to totally wipe out the other. We need to work on alleviating the trauma, and the way to do that is first and foremost for each side to hear the story of the other and to be able to tell its own story. I am pro-Israel and pro-Palestine both. I would argue that you cannot be pro-Israel without being pro-Palestine. Israel’s fate is intrinsically tied to the fate of Palestine, and vice versa.

Step two is overcoming the domination worldview and instead establishing caring and kindness as the path to security. And to do this you have to defeat the idea that anybody who believes in generosity is a fool. There’s a Hebrew word, freier, that means somebody who is so idealistic and good-hearted that he or she ends up being walked on by everybody else. Israelis fear they will appear to be freiers. That fear has to be overcome, just as in the U.S. liberals need to overcome the fear of humiliation, of having trusted in Obama and been disappointed.

Of course there are times when the Other does not act according to his or her highest values, but nevertheless we need to help people feel safe enough to choose caring over control. I think that’s more likely to come from a movement that starts in the West than one that starts in the Middle East. If we can change the dominant discourse in Western societies, it will have a tremendous impact on the peace movement in Israel and Palestine.

Leviton: You write, “Palestinians have a government more open to compromise and a population more anxious to achieve peace than ever.” That’s certainly not the picture we get from the U.S. or Israeli governments. Hamas especially is considered dangerous. Where do you see this ripeness for peace?

Lerner: The Palestinians have already proclaimed their recognition of Israel several times. And the Palestinians have said they want a state in the West Bank and Gaza with some geographical continuity between them. Israel won’t say what it wants its borders to be, but the peace-oriented Israelis want to make a compromise that will allow Israel to retain control over holy sites in Jerusalem, the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem, and a few of the nearby settlements in the West Bank. Essentially they’ll trade 5 percent of what’s currently Israel for 5 percent of the West Bank, as long as the land is equally valuable. So the terms of the agreement are there, but no political compromise is going to work unless there is a change of heart and a change of consciousness on both sides.

The core elements of Hamas will never disappear. That’s why, after an agreement is signed and implemented, I call for an international force of Israelis, Palestinians, and other governments to protect citizens of both countries from the extremists on the other side. We will need this because there will be Israelis and Palestinians who will fight any deal that involves equality and fairness. There are people to be feared in both communities. There are Israelis who say that Israel’s borders should be what the Bible says, which would mean all the way to Baghdad. Palestinians who were not fundamentalists thirty years ago have been attracted to Islamic fundamentalism, partly because of Hamas’s social services. The strength of Hamas comes from its ability to provide services for those living in Gaza that the Palestinian Authority can’t or won’t. And fundamentalism is increasing partly because the conditions of the Occupation cause people to look for fulfillment in the next world. When people despair of finding a decent life in this world, they are willing to become martyrs. How do you counter that? Give them a decent life here, or at least make one possible.

Leviton: You’ve described the settler movement in Israel as a kind of idolatry.

Lerner: Settler Judaism is idolatry because it’s based on the assumption that power is the only way to achieve security, thus denying the biblical God who is revealed as compassionate and merciful and who delivers chesed (lovingkindness) to the thousands. These settlers don’t believe in God’s command to love the stranger and give that stranger equal rights. But that doesn’t mean I think most settlers are evil people or that we shouldn’t also care about their well-being when working out a peace settlement. Those settlers who want to stay in the West Bank should stay there, but as citizens of Palestine, just as more than a million Palestinians are living in Israel today under the laws of Israel. I respect the settlers’ religious commitment to live in the Land of Israel, but the Bible doesn’t say that Jews must exercise political sovereignty under a Jewish-only government; it doesn’t dictate what the government will be. So let Israelis live anywhere in the ancient Land of Israel, but let them conduct themselves according to the laws of the government there, which in the West Bank and Gaza will be a Palestinian government. And they must live as Palestinian citizens and give up their Israeli citizenship. Such settlers will still be fulfilling their religious beliefs by settling in the whole Land of Israel.

There should be a fund to assist those settlers who want to move back inside Israel, because many moved to the West Bank for financial reasons: they got a special deal from the Israeli government to live in the West Bank when they couldn’t afford comparable housing inside pre-1967 borders. Many of those people would be willing to move if they had enough money to buy comparable housing inside Israel.

Leviton: You have had your home vandalized by those who disagree with your opinions about the Middle East, and you have been attacked as a “self-hating Jew.” Where do you draw the line between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism?

Lerner: I don’t call myself a Zionist. That term has become so misused that I don’t use it. I’m a religious Jew. My commitment is to serve God in the best way I possibly can. And that involves wanting the Jewish people to do well and be safe. I moved to Israel, and my son, my only child, went into a combat unit of the Israeli army, the paratroopers. This is not the action of a self-hating Jew! I love Israel and want it to survive. But I say, let Israel be known not as the strongest military force in the Middle East but as the most caring and loving force. Then Israel’s survival will be assured. The only Judaism that is sustainable in the twenty-first century is an emancipatory Judaism of love. But our fate as Jews depends on the well-being not only of Jews and Palestinians, but on the well-being of everyone on the planet and on the well-being of the planet itself.