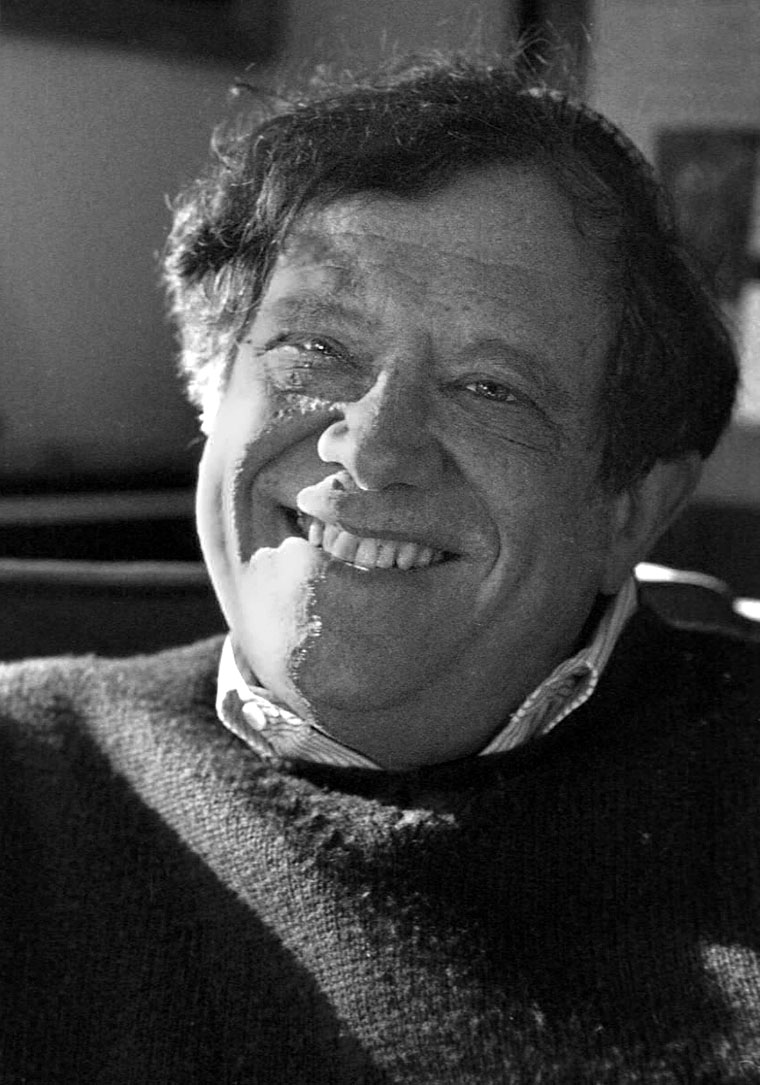

Michael Lerner, the editor of Tikkun magazine, is often at the center of controversy, especially for his position on the complex Palestinian-Israeli conflict. But in his quest for a middle ground, Lerner has emerged as one of the more balanced voices in the debate.

Lerner’s latest book, Healing Israel/Palestine (Tikkun Books), encourages each side to acknowledge the pain and affirm the fundamental decency of the other. Lerner’s attempts to be pro-Israel and pro-Palestine have provoked criticism from both sides — and even death threats.

Now sixty-one, Lerner grew up in Newark, New Jersey, in a household immersed in politics. His parents were leaders in the Zionist movement in the U.S. before World War II. After the war his father became a judge and his mother a political advisor and campaign chair to a U.S. senator. Democratic icons like Adlai Stevenson and Harry Truman passed through the family’s home as Lerner was growing up, and when he applied to college, John F. Kennedy wrote him a letter of recommendation.

By the time Lerner was twelve years old, he was reading the Congressional Record and noticing the difference between what politicians said and how they actually voted. He saw hypocrisy within Judaism, as well. Says Lerner, “On the one hand, the synagogues of the 1950s were filled with people who articulated high ideals; on the other hand, it was obvious that the real bottom line was materialism and conspicuous consumption.”

Then Lerner discovered Abraham Joshua Heschel’s book God in Search of Man. For years he read a chapter a week, and when he’d finished the book, he started over. As a teenager, Lerner got to meet Heschel, who invited him to come study at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. There, Lerner discovered that some Jews rejected the Americanized Judaism that he knew, suggesting it had little to do with the core of the religion. It was his first encounter with a Jewish critique of Judaism, and it laid the groundwork for his later campaign for a renewal of the core faith.

In 1966 Lerner lived for several months on a kibbutz in Israel. Although the socialist environment of the kibbutz showed him that people could be motivated by nonmaterial rewards, it also revealed what he saw as the central flaw of socialism: the absence of a spiritual element.

By the late sixties, Lerner had become a leader in the antiwar movement in the U.S. He was a member of the Seattle Seven, a group of activists indicted by the federal government for using the facilities of interstate commerce (the telephone) with the intent to incite to riot — i.e., a protest against the Vietnam War. FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover called Lerner “one of America’s most dangerous criminals.” Lerner was jailed at Terminal Island Federal Penitentiary for contempt of court. The conspiracy charges were later dropped and the laws under which they had been brought declared unconstitutional.

When the antiwar movement lost steam, Lerner attributed some of the responsibility to what he called the “surplus powerlessness” of the activists themselves. They couldn’t recognize their own successes, he says, because “they continually redefined the criteria for success in a way that made them feel like failures.” A desire to understand this self-destructive “pathology” led Lerner to study psychotherapy. He also wanted to examine his own emotional life. Says Lerner, “I found myself being too judgmental, particularly in regard to my parents.” He finished his second PhD (his first was in philosophy) at the Wright Institute in 1977 and went to work as a clinical psychologist.

In the late seventies and early eighties Lerner became increasingly distressed at a political shift in the Jewish community from liberalism to conservatism. This eventually led him to found Tikkun magazine in 1986. His goal was to revitalize the liberal and progressive voices of American Jews. But Lerner’s activism isn’t limited to the Middle East and Jewish American circles. Today Tikkun (the name means “to heal or transform” in Hebrew) helps liberals of all faiths integrate the spiritual and the political in their lives. Lerner recently formed the Tikkun Community, an interfaith group — it even welcomes agnostics and atheists — committed to nonviolence, global consciousness, and ecological sanity.

As a rabbi, Lerner leads services in several locations in San Francisco. His congregation, Beyt Tikkun, is an outgrowth of the Jewish Renewal movement, which combines spirituality with a call for social change. Lerner’s book Jewish Renewal: A Path to Healing and Transformation (Perennial) outlines his plan to reclaim Judaism’s revolutionary spirit. He expands the discussion to all faiths in Spirit Matters (Walsch Books / Hampton Roads).

Lerner is currently mobilizing people from every U.S. Congressional district for the Tikkun Community’s second annual Teach-In to Congress for Middle East Peace, April 25 through 27 in Washington, D.C. Their goal is to convince Congress that many Americans do not support the Occupation or the building of a wall inside the West Bank — “not because we oppose Israel, but because we see its current policies as self-destructive and a violation of the highest values of the Jewish people. We believe it is in America’s interests, and Israel’s, and the Jewish people’s, to seek peace and reconciliation, and we invite others to join us in D.C.” (To learn more, visit www.tikkun.org.)

Lerner has lived in the Berkeley hills since 1986. He has a thirty-one-year-old son, Akiva, and recently became a grandfather. We spoke in his living room, which is packed with books on many topics, including transpersonal psychology, philosophy, and politics. In person Lerner is passionate, down-to-earth, and tireless. A portrait of him as a young boy hangs on the wall. Though decades have passed since it was painted, he still projects the same sense of youthful optimism.

Lerner welcomes correspondence and can be reached by e-mail at RabbiLerner@tikkun.org.

MICHAEL LERNER

Cooper: Let’s begin with the legitimacy of Israel. You talk of not blaming either side in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Doesn’t this cover up the fact that one people came to another people’s land and dislocated them?

Lerner: There is no land on this planet that hasn’t been taken through force from someone who lived there before. In my view, nobody has any legitimate claim to a particular land. The Jews returned to their ancient homeland and came into conflict with a largely Muslim group of people whose ancestors had taken it from the people who had lived there before, who were descendants of a group who had conquered it under the Romans. Before the Romans came the Greeks. Before them there were the Persians, and before them the Babylonians, and before them the Jews, and before the Jews there were others whom we Jews dispossessed. This is true of every place on the planet, and especially here in the United States.

So instead of focusing on whose ancestors give one a right to own a particular land, we need a new discourse that focuses on our common responsibility. The Torah puts it this way: “God says, ‘The whole world is mine.’ ” The point is that there is no absolute right to private property or ownership of a particular land by a particular people. I believe our responsibility is to share this globe and its resources equally with every person on the planet in a way that is ecologically sustainable.

Let me make an analogy here. Let’s say I live on land that my ancestors built up and made into what it is today. Suddenly another group arrives wanting to live here, as the Jewish people did in Palestine. And the way these newcomers live is very different from the way I live. Do I have a right to keep them out? The Irish of Boston thought they did. They said that blacks who were coming up from the South in the 1970s had no right to live there or go to their schools. “We built this town from scratch,” the Irish said. “They’re going to destroy our culture. They’re going to bring different values and lifestyles. And they are going to take over our cities.”

To the fact that Southern blacks were an oppressed people in need of a place to live, the Irish responded, “We didn’t oppress them. We even sent troops to the Civil War to end their oppression. Why should we continue to solve their problems?” Eventually the federal government stepped in and told the Irish that blacks would be allowed to live there and go to integrated schools.

This is very similar to the situation that faced the Jews before World War II. Some of them wanted to go back to their ancient homeland, but the Palestinians said, “We have no place for you here. This is our society. We built it, and you’re going to destroy everything.” The Palestinians had no similar rule against Arabs coming in. In fact, they welcomed Arabs. They just didn’t want Jews. It wasn’t about there being too many people in the area; it was about who the people were. And this was precisely what Jews have faced for two thousand years, since Roman imperialism threw us out of our land — everywhere we went we were seen as a threat because we brought our own values and our own culture and language. And though we were refugees, we were always perceived as somehow having the magical power to overwhelm everyone unless we were dominated first.

Do countries have the right to exclude people based on ethnicity or religion or national background? I say no. I would not support the U.S. having an ethnic criterion — as it did for a long time — for who can come here. I think we have a right to set a limit on the number of immigrants, so that we don’t have an ecological disaster. But admission should not be based on ethnicity. The Palestinians’ refusal to admit Jewish refugees was fundamentally racist and illegitimate.

Some early Zionists were socialist internationalists who envisioned a Jewish society that might exist in harmony with Palestinians. But the hostile reception from Palestinians weakened the influence of those internationalists and strengthened the hand of the most right-wing Jews, who said, “We shouldn’t be surprised that the Palestinians are hostile — they are just like all the other non-Jews in the world. That’s precisely why we need a state of our own and an army of our own, and why we can’t build a society based on cooperation with Arabs, who don’t want us here any more than people anywhere else on the planet want us there. Everyone is against us, so here, in our ancient homeland, we will take our stand and create a safe place for Jews.” The influence of this more nationalist thinking increased during the Second World War. Jews were being murdered by the millions in Europe, but the Arabs used their influence to convince the British not to allow any Jewish refugees into Palestine.

After World War II, the UN declared that Jews had the right to build a state for themselves in Palestine and urged the creation of two states, but Palestinians rejected that plan and insisted that they wanted only one state (in which they would have been the majority). War broke out between the Palestinians and the Israelis. Soon the surrounding Arab states also declared war on the new Jewish state. Some Arabs living in the area were forcefully uprooted from their homes by acts of Jewish terror or by forced evacuations. But a greater number fled out of a reasonable fear that they might become victims of this war. Most Jews saw themselves as fighting a last fight of survival. Unlike the Palestinians, who could flee to neighboring lands, the Jews had no place to go for safety — this was it. They had just seen their own people massacred during World War II. It’s no wonder that many agreed with the right-wing, ultranationalist Jews’ claim that Jewish safety and security could come only from expelling Palestinians. They felt justified in doing this because of the way the Palestinians had behaved toward Jewish refugees.

After the war, Israel refused to let these refugees come back to their homes. Since not all Arabs had fled — hundreds of thousands had stayed — the Israeli government said that those who did flee had identified with the enemy and were not allowed to come back. Now, I think that Israeli policy was a terrible, tragic error, and morally unacceptable in the same way that it was morally unacceptable for Palestinians not to have allowed Jews to immigrate in the first place. But to sum up the whole conflict by saying, “Jews came and expelled the Palestinians,” as some on the Left like to say, demonizes the Jews and obscures the complex reality in which both sides cocreated this mess.

Jews jumped from the burning buildings of Europe and landed, unintentionally, on the backs of the Palestinians. Because our pain was so great from the Holocaust, we didn’t notice the pain we caused them. Nor could we understand how they could see us as aggressors or colonialists when we had been the primary victim of the European colonial powers for two thousand years, and had also been the victim of apartheid-like conditions in most Arab states (which still treated us better than we were treated by Christians). The Palestinians were furious at us for coming there, perceived us to be a threat, made no attempt to reach out and build bonds of understanding, saw us as modern Crusaders (though the Crusades had also targeted Jews), and acted in violent ways that validated the most paranoid Jewish perceptions of Arabs. Ultranationalist Jews then acted in violent ways that confirmed the Arabs’ most paranoid perceptions of Jews.

Cooper: Which brings us to where we are today.

Lerner: Yes, we are now looking at two peoples who have come to a moment of despair and mutual hurt and cruelty. I do not claim that these sides are equal in power. Israel is the occupying army. In 2002, Amnesty International issued a report on war crimes committed by Israeli troops in Jenin and Nablus, including unlawfully killing Palestinians, blocking medical care, using people as human shields, and bulldozing houses with residents inside. Yet Amnesty also made it clear that some Palestinian militants have engaged in attacks on Israeli civilians that can only be described as crimes against humanity. The deliberate targeting of innocent civilians is unacceptable in any civilized society.

Cooper: How do you explain suicide attacks?

Lerner: An occupation turns ordinary civilians into terrorists. If you control a population against their will, violate their basic human rights, use them as hostages and human shields, torture their young men, and impose twenty-four-hour curfews under threat of death, then you will find yourself fighting ordinary civilians, because that’s whom you are oppressing.

But the blame game makes no sense. Both sides have a story to tell. The Occupation did not start this struggle, but it has made it far worse. To end it will require a breakthrough in consciousness on both sides. Such a possibility seems more and more remote as the hurt increases.

Jews jumped from the burning buildings of Europe and landed, unintentionally, on the backs of the Palestinians. Because our pain was so great from the Holocaust, we didn’t notice the pain we caused them.

Cooper: What has been the media’s role in perpetuating stereotypes on both sides?

Lerner: The media rarely present voices that seek peace, which creates the impression that there are no such voices. Many Jews have been told that the only way to be a good Jew is to support the Israeli government, no matter how immorally that government acts. Few know about the tens of thousands of us who are building a progressive Judaism that affirms the rights of the Palestinian people. Many Jews feel they have to choose between their Jewishness and their moral center, and they end up distancing themselves from the Jewish world — because many Jewish institutions are dominated by conservative and morally insensitive people who make everyone who questions Israeli policy feel that they are “self-hating Jews.” Few Jews even know that there are hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who desperately want an accommodation with Israel so that they can live in peace. When I go to speak at synagogues or churches, people often ask, “Why is it only Jews who want to reach out to the other side?” The answer, of course, is that the mainstream media never quote Palestinians who want peace. But you can read about them in Tikkun or at www.tikkun.org.

Cooper: What’s being taught now in the synagogues and Hebrew schools? When I was growing up, I was taught that the Jews were good and the Arabs were evil.

Lerner: In many Conservative and Orthodox synagogues, it’s the same as it’s always been, or worse. While there are some notable exceptions, most identify exclusively with the very real pain faced by Israelis and close their eyes to the suffering of the “other.” In the Reform and Reconstructionist and Jewish Renewal movements, there is more focus on social justice, but many of their young people tell me that when they try to bring up the issue of social justice for the Palestinians, they are ignored. That’s why we at Tikkun, and those in the progressive sections of all Jewish movements, are building a global Judaism that can address the need for healing and transcend Jewish chauvinism and the conceit that our pain is more important than everyone else’s pain. This emerging global Judaism must reject or transform every part of our tradition that leads Jews to be insensitive to the pains of the other or insensitive to the vast ecological crisis facing all humanity. What the planet needs is for us to overcome separation and recognize the fundamental unity of all human beings. And that means really caring about the other, not just mouthing pious words while actually living a life in which we hoard the goodies of the planet for ourselves. (Here I’m thinking of the U.S. in general, not Jews in particular.) We need to repair the damage of 150 years of both capitalist and communist industrialization. Any religious system that prevents us from doing this should be transformed.

Acting from love and kindness is a privilege. . . . Those of us who insist that the solution lies in cooperation and generosity are not on a higher moral plane. We are just less oppressed.

Cooper: How does anti-Semitism shape Jewish thought and attitudes?

Lerner: By the time the Jews came along, the world was already class-stratified. A few people had great power, and most had very little. The wealthy and powerful elite traditionally maintain power through force and by convincing people that nothing can be done to change things. They also convince people that some “other” — a neighboring group or minority — is causing all the problems.

The Jews arrived on the scene with an ideology and a Torah that said the world can be fundamentally changed. We knew that anyone who said that hierarchical oppression is built into the structure of the universe was lying, because we’d been slaves and now we were free. It was a revolutionary message that generated a tremendous amount of resentment among the ruling class. They didn’t want people to hear this message. So the ruling elite of the ancient world demeaned the Jews and tried to convince people to hate us. That was the beginning of anti-Semitic attitudes in the ancient, pre-Christian world.

Most Jews didn’t want to be in conflict with the powerful, so they turned away from the revolutionary aspects of their own tradition and tried to convince the powerful there was no need to worry, that Judaism was not really a way of life, which is how the Torah described it, but “only a religion,” narrowly confined to the spiritual side of one’s life. Particularly after the Jews were conquered and oppressed by the Greeks and the Romans, the revolutionary message of hope and transformation seemed less and less real, and those who sought to play down that message and play up the message of accommodation had greater influence. Gradually, Judaism became less of a revolutionary practice. Still, its Exodus story, told every week in the Torah readings and each year on the major Jewish holidays, retained the revolutionary consciousness, and Jews kept a culture of rebelliousness and lack of respect for secular power and authority that confounded the Romans until they expelled most Jews from their homeland, which the Romans renamed Palestine.

Once the Christian Church became the dominant power, it had yet another reason to oppress us: we said Jesus was not the Son of God, and he certainly wasn’t the Messiah, because our texts had defined the Messiah as the person who would bring a period in which the lion lies down with the lamb and nations beat their swords into plowshares. Jesus didn’t bring an era of peace to the planet, so from the Jewish perspective, it was obvious that the Messiah had not yet come. That made the Christians’ anger toward the Jews even more intense.

Christians made laws restricting where Jews could live and what we could do for a living, and made it illegal for us to convert anyone to Judaism or to have communications with Christians except in narrowly prescribed areas. They claimed that we Jews had mysteriously managed to wield power over our Roman oppressors at a pivotal moment, and had used that power to convince the Romans to crucify our brother and teacher Jesus. So we were blamed with “killing God.” Each year, when the story of the crucifixion was retold, angry mobs would assault the Jews. And from time to time we were driven out of cities or massacred. This led many Jews to feel a great deal of anger at non-Jews. They said, defensively, “We’re the chosen ones. We’re better than other people, because we don’t do to them what they do to us.”

Instead of lessening after the end of feudalism and church rule, anti-Semitism got worse. The new ruling elite of Western capitalism needed an “other” to blame for the failures of the capitalist order to satisfy the fundamental needs of their own populace. And so they could draw upon the church-generated hatred of Jews and revive it in a modern and even more lethal semisecular form. By the twentieth century, the ground was laid for the Holocaust. After that, Jews came to believe that our only guarantee of security and strength would be to have our own state and our own army. Israel was an answer to the abject powerlessness of the concentration camp.

Cooper: Nowadays it seems that Jews are no longer thought of as an oppressed minority, especially by progressives. Why is this?

Lerner: Jews were not thought of as an oppressed minority in Germany and Poland during the first thirty years of the twentieth century either. That’s because the Left has a narrow understanding of oppression. It believes that oppression is measured by economic standing or by explicit laws. Since there weren’t any explicit laws against Jews, and they were succeeding economically, the Left never dealt with the anti-Semitism growing all around them. Then came the thirties and forties and the upsurge of fascism. One out of every three Jews on the planet was murdered. And the Left had no explanation for it.

Add to this narrow view of oppression the fact that there’s good reason to be critical of the state of Israel today, and you’ll see how the Left is able to fall into anti-Semitism. It says that Jewish oppression is over. Well, it’s not over, and the criticisms that are being put forward against Israel are good evidence. Although many of these criticisms are correct — and for that reason we in the Tikkun Community are adamant in our critique of the wall being built through the West Bank by the Israeli government, and adamant in our critique of the Occupation itself — some of the criticisms are being made in anti-Semitic ways.

Cooper: What would be an anti-Semitic left-wing criticism of Israel?

Lerner: To understand this, you have to understand how the same criticism can be made in both a legitimate and an anti-Semitic way. I’ll give you two analogies.

Number one: A candidate for public office goes around the country talking about black crime. When people challenge him, he cites statistics showing the disproportionate number of blacks who have been arrested and are in prison. Everything he says is true, but most people would call him a racist. Why? Because there’s a larger context that he is not mentioning — namely, that the justice system doesn’t prosecute blacks and whites equally. So it can be racist to separate the facts from the larger context, even if your facts are correct.

Here’s a second analogy: Say you’re a member of your neighborhood association, and a person gets up at a meeting and says, “Your child is making a lot of noise, and it really bothers me.” Actually your child is one of a group of kids who are making noise, and yours isn’t the worst of them. Still, you go home, criticize your child, and try to convince him not to take part in this behavior. But it doesn’t work. At the next meeting, the same neighbor gets up and says your child is still making a lot of noise. If this happened a few times in a row, you would think that this person, although correct that your child made noise, was singling out your kid for some reason that had nothing to do with your child’s behavior.

Sections of the American Left today are criticizing Israel in ways that do just that. They ignore the historical context of two thousand years of anti-Semitism, and they criticize Israel disproportionately in comparison to other governments that are engaged in equally bad or worse activities. For example, in the demonstrations against the war in Iraq, the group ANSWER constantly raised criticisms of Israel, but never once mentioned the human-rights abuses of Saddam Hussein, or, for that matter, the oppression people face in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Syria. Or the occupation of Tibet by China, or the occupation of Chechnya by Russia.

Still, this doesn’t mean that the criticisms of Israel aren’t correct. The Occupation is, in the view of the Tikkun Community, not only immoral but self-destructive. And to enforce it, the Israeli army has engaged in acts that violate international standards of human rights to such an extent that hundreds of Israelis now refuse to serve in the West Bank and Gaza.

Cooper: You have been called anti-Semitic by members of your own community. A recent letter in Tikkun called you a “disgrace” and a “traitor.”

Lerner: I get death threats almost weekly. Some people say that I’m worse than Hitler. They say they hope that I will die soon, or that they will kill me. They’ve threatened the people who work for Tikkun. I don’t like it. On the other hand, I try to have compassion for these people, because they, too, are the products of a world of pain and cruelty. And I pray that someday they can see that we who disagree with them are disagreeing not out of hatred for the Jewish people, but out of love for the Jewish people.

What worries me is that there are an awful lot of people who are scared to join the Tikkun Community and forge a path that is both pro-Israel and pro-Palestine because they, too, might get attacked. There are also many Christians who don’t feel comfortable criticizing Israel because they will be labeled anti-Semites by the pro-government forces. One of my tasks is to help non-Jews understand that it is not anti-Semitic to criticize Israeli policies, as long as you don’t deny Israel’s right to exist.

The profligate misuse of the charge of anti-Semitism is bad for Israel. A similar problem occurred with “political correctness” in the 1980s. A debate arose on college campuses over the language used to talk about race and gender. Many who didn’t use the correct terminology were unfairly labeled racist or sexist. This led to a backlash in which right-wingers came forward and said that racism and sexism were not a problem anymore, that the civil-rights movement and the women’s movement had so much power that now it was the people who weren’t “politically correct” who were being oppressed. Even people who had been a part of the Left had some sympathy with that right-wing reaction, because too many people felt they had been silenced by “political correctness.” They resented being told how to talk and what to think, and they felt oppressed by the forces that said they were against oppression.

I fear the same thing is going to happen with anti-Semitism — that people will feel so resentful over having been called anti-Semitic for making criticisms of Israel that they won’t be ready to fight against the real deal when it raises its dirty head again, as it is already doing in some right-wing Christian circles and some left-wing, supposedly anti-imperialist, circles.

Cooper: The United States originally armed Israel because it needed an ally against communism. Now the Cold War is over, and the U.S. still gives Israel billions of dollars a year. How legitimate is this relationship?

Lerner: U.S. support for Israel has two bases: the military and economic interests Israel shares with the U.S. elite; and the democratic and spiritual values held in common by the American and Israeli people. I believe that these democratic and spiritual ties are being weakened by Israeli behavior toward Palestinians. Those ties may someday break, leaving only the military and economic connections. If that were to occur, it’s not hard for me to imagine circumstances in which the American elite would decide it was in their best interest to abandon Israel and side with some of the Arab states, which have more oil and more potential consumers.

Cooper: You have said that Israelis and Jews have difficulty acknowledging their own power because they have been so brutalized. What’s it going to take for Israelis to realize that they do have power?

Lerner: Today neither side seems to think it has the power to change the situation. Either side could change all this by taking a repentant and generous attitude toward the other. For example, if Israel were to announce an end to the Occupation and approach the Palestinians with an open heart, a sense of repentance, and a request for forgiveness, we could see the end of the conflict within a year or two. Even if Palestinian extremists did engage in further acts of violence, they’d be opposed by their own neighbors.

Similarly, if the Palestinians were to follow a strategy of principled nonviolence and approach the Jewish people in a spirit of repentance for the violence that has been committed against Israeli civilians — and if they were to isolate the extremists in their community and treat them not only as criminals but as morally offensive people — they would within a few years have a Palestinian state in all of Gaza and the West Bank.

Cooper: Foreign-policy analyst Mitchell G. Bard says that there is nothing Israel can do to bring about peace, because a large percentage of Palestinians believe Jews cannot be allowed a state in the Islamic heartland.

Lerner: There were also many who predicted, after the Second World War, that France and Germany would never be able to live in peace. I believe that Bard’s statement will one day be looked upon as yet another example of the bizarre distortions of consciousness that happen when people live in a state of war. The only thing that will prevent peace from becoming a reality is the ethos of selfishness and cruelty that dominates both sides at the moment.

Cooper: In your book Healing Israel/Palestine you say there’s no way to avoid one’s own biases when relating history. What are your biases?

Lerner: There’s always a selection process when one looks at any set of historical events. If we were to describe events objectively and include all the facts, it would take more time than the event itself. So the question is: What’s your principle of selection? What’s important to you? The answer is shaped by your goals. The parts of any history that interest me are those related to the possibility of healing and transforming the world, because these are my goals.

Cooper: You’ve said that the Holocaust caused the majority of Jews to turn inward and focus on the Jewish state, while a minority, like yourself, started to fight for social justice. Why did you go in that direction?

Lerner: Acting from fear is sometimes the only option for the oppressed. Acting from love and kindness is a privilege. I was more privileged than others. I was less traumatized. Those of us who insist that the solution lies in cooperation and generosity are not on a higher moral plane. We are just less oppressed.

Cooper: But your family was decimated in the Holocaust.

Lerner: That’s true. But I grew up in the post-Holocaust period, and my immediate family had the benefit of security in the U.S. My parents also had a peculiar sense of self-confidence. Not many Jews had this. My mother was a very powerful woman at a time when not many women were allowed to have power. I personally benefited from seeing my mother defy the stereotype of what women were supposed to be. It gave me the confidence to follow my own intuitions about the world.

Of course, that drove her crazy, because my ideas were different from hers. She had hoped I would become the first Jewish senator from New Jersey. She was confident that, if I graduated from law school, she could get me a safe Democratic seat in Congress.

Cooper: She didn’t want you to become a rabbi?

Lerner: She was horrified that I was becoming a rabbi. She didn’t think it was a good profession for a Jewish boy. [Laughter.] She thought it was downwardly mobile.

Cooper: And your father?

Lerner: My father was more accepting of my path. His father’s father was a rabbi, so a part of his heart was open to that.

Cooper: How hard is it for you to live up to your ideals?

Lerner: I’m a deeply flawed human being. Though I advocate compassion, I often catch myself judging others. I have to remind myself to think of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld with compassion. And although I believe in the oneness and unity of all with all, I sometimes find myself demonizing those who live at the top and won’t share the wealth with others. I also get annoyed at myself, my co-workers, my allies, and my friends for not doing enough to end the oppression. I sometimes feel that we are not serious enough, not smart enough, not committed enough, and are not putting enough of our time behind our ideals. In short, I fall back into the very pattern that undermined the sixties Left: not giving enough credit to people who are doing their best to work for social change. So I have lots of work to do on myself.

Cooper: What is your own spiritual practice like?

Lerner: Each morning I meditate and pray. Each evening I pray again and try to review the day’s events and forgive anyone I feel has wronged me or those I love. I also try to say a hundred blessings a day — celebrating all the wonderful aspects of my life and the universe. Then, from just before sunset on Friday to after dark on Saturday, I participate in the Jewish practice of Shabbat. During this period I shut down my computer, turn off my phones, do not use money, do not “catch up” on errands, and do not cook or shop or read manuscripts or anything even vaguely related to work or “getting things together.”

Instead I meditate, pray (usually with my congregation), and take long walks in nature. I study, teach, sing, dance, and celebrate the universe. Shabbat puts me into a spiritual space that I can’t access through an hour of daily meditation. The tradition of Shabbat also emphasizes pleasure: good food, good sex, and good company. This practice has been a lifesaver for me and for many people in my synagogue in San Francisco.

Cooper: You’ve said, based on your study of history and your experience working with couples and families, that most struggles are cocreated by those involved: both sides are right, and both sides are wrong. How can this be?

Lerner: Reality is much more complex than any judgment of right and wrong encourages you to believe. When you really understand the ethical, spiritual, social, economic, and psychological forces that shape individuals, you will see that people’s choices are not based on a desire to hurt. Instead, they act in accord with what they know and what worldviews are available to them. Most are doing the best they can, given what information they’ve received and what problems they are facing. If you understand how that’s true for everyone, it’s much harder to be judgmental about a particular person.

Our actions are shaped partly by our history and partly by everybody else’s. For example, readers of The Sun may be extremely generous and kind people, but they are not giving all they have to feed the hungry. It’s not that they — or I, because I’m not doing it either — are evil people. Rather they’ve based their decision on what they feel is possible and what their concerns are about the future and what everyone else is doing. Their decision is also based on how our society is organized and the difficulty of arranging to get food to people without becoming a victim of fraud or some homeless person’s potential pathologies.

An outsider looking at the world today and seeing more than two billion people — a third of humanity — living on less than two dollars a day might say the rest of us are all unbelievably selfish. And I wouldn’t necessarily disagree, but I’d say that judgment ought to be tempered by a recognition of the limits and constraints on our consciousness.

Our current situation is cocreated. Each of us is partially responsible for creating this world in which one out of every three people doesn’t have enough to eat, but it’s only a partial responsibility. We need to change, but we also need to have compassion for one another.

Cooper: But aren’t some individuals simply evil, like Hitler, for example?

Lerner: When we look at Hitler, we see that he could not have done what he did in a vacuum. A whole world cocreated that reality. For example, science separated itself from ethics and allowed for the possibility that technology itself would become “value netural,” and so the technicians no longer felt it was their responsibility to make moral assessments of how their inventions were being used. Some have misused the scientific worldview to such an extent that they now think they have no moral responsibility beyond the narrowly framed professional ethics. (“Tell the truth about your experiments,” for example, but not “Make sure that your science contributes to the well-being of humanity.”) They don’t feel the need to bring broader ethical considerations to bear on their work.

I’m thinking of nuclear weapons, but I’m also thinking of the way in which the life-support system of this planet is being destroyed by the technologies developed by scientists and engineers. Many of them are very decent people, but they have distanced themselves from responsibility for how the technologies they develop are going to be used. That’s not their issue, they say. Their issue is just to develop them. These larger issues have nothing to do with their professional life and must be left to those empowered to make those decisions — which, in the case of contemporary America, increasingly means leaving it to the consumer marketplace.

This attitude is what makes it possible for us, people with good, decent instincts, to watch as the planet is being destroyed and not do much about it. Each of us thinks, I’m not the cause of the destruction, I’m just doing my job, and it would be arrogant for me to introduce my moral judgments into the public sphere, where they don’t belong.

In the case of prewar Germany, it was also conditions of extreme economic deprivation in Germany that made people vulnerable to ultranationalist and racist ideologies. After World War I, the great powers bled Germany dry and unfairly punished the German people, which paved the way for fascism.

And in order to fully tell the story, we also have to look at how capitalist social relations in Europe created a nostalgia for precapitalist days when there was more of a “we,” a sense of community among people. In a desperate situation, when people are feeling extremes of alienation and loneliness, the ultranationalists come along — or, in other cases, the ultra-religious people — and say, “We can create a we. The only problem is, there’s a non-we that’s stopping us.” In Germany, that non-we was Jews. In America, it was blacks. In France today, it’s Arabs.

So Hitler didn’t come to power because a bunch of evil people suddenly dropped from the sky; rather, a people made desperate by an unfair treaty and a capitalist marketplace fell prey to nationalist propaganda.

This situation was cocreated by all of us — including the Jews! All of the Jews who were alive in the years before the Nazis came to power were doing the same thing everybody else was doing: looking out for ourselves, trying to make sure we benefited as best we could in Weimar Germany while others were starving or in deep desperation. Does that mean the Jews deserved it? Absolutely not! Nobody deserves the cruelty and pain that were inflicted by the Nazis. But many Jews were living according to the ethos of the capitalist marketplace and not paying attention to what was going on around them. A number of Jews got involved in the Socialist and Communist Parties, but most were just pursuing their own self-interest. Are they to blame? Only to the same degree that all of us are to blame for cocreating the contemporary ecological crisis that threatens all life on the planet.

Cooper: After terrorists destroyed the World Trade Center, some liberals blamed U.S. foreign policy for giving the Arab world reason to hate us.

Lerner: I reject the notion that somehow America deserved to be attacked on September 11, 2001. But I also think it’s a fantasy to believe that once we wipe out Bin Laden and his al-Qaeda organization we will be “safe.” The Bush administration and the right wing have taken the threat of terrorism and used it to revive the deeply held conservative belief that the world is primarily a dangerous place in which our most rational goal is to protect ourselves from threatening “others.” In my view, we need to find security not through armies or counterviolence, but through building a world of love and openheartedness. We need to choose hope over fear not only because it is more consistent with the sanctity of human life, but because it is the path that will lead to greatest security.

As a first step, I would suggest tithing: Let’s take 10 percent of the gross national product of the advanced industrial societies for the next thirty years and dedicate it to eliminating poverty, homelessness, hunger, and inadequate education and healthcare in the underdeveloped countries, and do it in a way that is respectful of the cultural traditions and ecological needs of those societies. That would do more to eliminate terrorism than all the trillions of dollars Western countries would have spent on national defense in the same period. This kind of global Marshall Plan is far more realistic than any war against terror being envisioned by either the Republicans or the Democrats.

The U.S. should learn from Israel’s mistakes: Faced with a handful of terrorists, Israel has retaliated with sieges, border closings, and so on. But it has succeeded only in generating greater support for the terrorists and weakening the hopes for peace.

The growth of fundamentalism in the world’s religions is in part a distorted response to the distorted reality of globalization. Global capital is not only an economic system; it is a militant religion engaged in a crusade to remake every country in its image. It has its own moral code, which says that individuals should always look out for themselves, that it’s OK to hurt others to advance one’s own interests, and that sexuality is just another commodity for consumption in the marketplace. It seeks to impose these rules on other cultures as a prerequisite to their participation in the global economy.

In response, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, and Islamic fundamentalists have declared various forms of holy war. If the fundamentalists have their own sexist, homophobic, racist, or anti-Semitic beliefs, they also have some valuable sense of human solidarity, which is precisely what’s being undermined by the selfishness of the market religion. Much fundamentalist criticism of Western secular society is accurate: it aggressively promotes a mechanistic worldview and denies the validity of spiritual truth.

Cooper: What will it take to achieve what you’ve called “emancipatory spirituality”?

Lerner: We need to combine the energies of all the people who are trying to promote peace, kindness, generosity of spirit, and justice on the planet. We need to bring them together and let them recognize one another as partners in the same enterprise. Because right now these people don’t recognize each other. They are split apart. Although each part is making some valuable contribution, there hasn’t been an integration of these different parts into one larger movement. And a movement is what we desperately need, because without that, each part perceives itself to be relatively powerless.

Cooper: Do you think that capitalist forces are working actively to prevent this?

Lerner: I don’t think there’s any conscious conspiracy to stop people from developing solutions. There are certainly groups of capitalists who work together to help American or Western corporations dominate the world’s economy, but I don’t think that most of them understand the dangers of what they’re doing. I think they honestly believe that globalization will increase freedom and democracy.

When people do fully understand the ecological consequences of globalization, they don’t say, “How do we hide this from everybody?” They actually undergo a significant change in consciousness. Some of those who are most committed to challenging the globalization of capital are former officials of the World Bank or other major capitalist institutions. So capitalists are not evil or hurtful people. They just don’t get it. They argue that corporations have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize the profits of their investors, which must take priority over social responsibility.

People’s choices are not based on a desire to hurt. . . . Most are doing the best they can, given what information they’ve received and what problems they are facing. If you understand how that’s true for everyone, it’s much harder to be judgmental about a particular person.

Cooper: But you’ve also critiqued the political progressives, who presumably do “get it.” How are they missing the mark?

Lerner: Often political progressives understand only one dimension of the picture. It’s like the story about the blind men each feeling a part of the elephant. When asked, “What’s an elephant like?” one man describes a tail. Another describes a leg. A third describes a tusk. Each one has touched the elephant, but none gets the whole picture. That’s why integration is necessary.

The part of the elephant that you rarely hear about among progressives is the fundamental human need for a meaning to our lives that transcends the competitiveness of the marketplace and ultimately connects us with some truths about the universe. That hunger for meaning is just as important as the hunger for food or individual rights or democratic participation.

For thousands of years, there has been a struggle between two ways of understanding reality: one that sees the universe as a scary place filled with people who will seek to dominate and control you unless you dominate and control them first; and another that sees human beings as fundamentally connected and impelled by a spirit of generosity. While most of us realize that the world has both elements, in any given moment we tend to see the world more through one frame than the other.

It’s often hard for people to maintain the frame that emphasizes human kindness and love. It becomes even harder when religious and spiritual systems that were originally designed to preach that message are filled with people who no longer really believe that. So they preach love, but act as though what really counts is power and control. At that point, many of the rest of us start to distrust the spiritual truths. If those people who preach love are actually power-driven, then we can’t really believe that a different kind of world is possible. Instead of recognizing that the leaders of these traditions are themselves torn by the same inner conflicts as the rest of us, we react with feelings of betrayal, anger, and disillusionment about the ideals themselves.

As a result, there has been a growing rebellion against religion. The rebellion is based on legitimate outrage at the way religious institutions say one thing and do another.

In response, we’ve abandoned a worldview based on spirit and embraced a scientistic worldview which says that only that which can be verified through some kind of experiment or measurement is real. Anything else is a matter of personal belief and has no place in our public lives.

Now, the reality is that religions that abandoned their spiritual foundation and became focused on power did in fact become deeply oppressive. Many people today have rebelled against the hierarchical power relations, the sexism, the homophobia, and the hypocrisy they encountered in religious communities. And this rebellion against religion gets so deeply ingrained in the consciousness of progressives that they see all religion as wrongheaded and coercive. The distortions are seen as the totality, and the legitimate spiritual needs are no longer understood by many liberals and progressives.

They never question the degree to which the scientific, educational, political, and cultural institutions of this society are also racist, sexist, and so on. Instead they place disproportionate blame on religion and then reject it as fundamentally reactionary, and thereby cut themselves off from the very people they need to reach if we are going to construct a truly democratic and caring society. Similarly, many of my peers rejected the Judaism they knew growing up, thinking that it was the only Judaism. In fact it was a distortion, an Americanized version that bears little resemblance to the faith outlined by the Prophets. Again, they mistook the distorted part for the whole.

Now progressives find themselves without answers to any question that goes beyond the materialistic ethos of the contemporary world. The best they can offer is an end to economic and political deprivation. And I’m all for that; it is extremely important. And yet many who are not economically or politically deprived still hunger for something deeper. The progressive community can’t offer them anything. The only ones who are offering meaning are on the Right. Ironically, many on the Left quietly sneak off to a meditation practice or an ashram or a church or a synagogue, because they don’t feel they can acknowledge publicly inside the culture of the Left that they have this need for meaning that isn’t being fulfilled by involvement in progressive politics.

Progressives have become so estranged from and hostile to spiritual life that their movement is not sustainable. You find a preponderance of young people in progressive organizations because, as people get older, the organizations don’t meet their spiritual needs — so they go elsewhere. And that makes young people less willing to commit to a life of social change, because they don’t see many older role models within the movement.

It’s also true that spiritual movements need to integrate a political consciousness. No matter how much we talk about love and caring, if we live in a world where one out of every three people doesn’t have enough to eat, we’re not acting on love. And if we shut our eyes to the need to transform economic and political systems, we’re not really acting as spiritual beings. There needs to be an integration.

Cooper: When did it first occur to you that progressives had this lack? Was it when you were active in the sixties antiwar movement?

Lerner: At the same time that I was active in the sixties, I was also involved in my personal practice as a religious Jew. In fact, my commitment to social change came from my commitment to God and Torah. I quickly realized, however, that if I wanted to play a leadership role in the antiwar movement, I had to keep that part of my life under wraps. Whenever it came out, I lost respect and credibility. It was the same for everyone in the movement, unless you were African American, like Martin Luther King Jr. If you had a spiritual life, you wouldn’t be allowed to have any say in shaping the movement.

Still, I felt this was a personal problem that I had to deal with on a personal level. It wasn’t until twenty years later that I discovered this was not just my issue. In the eighties, as a psychotherapist, I did some work for the labor movement, exploring the shift in American consciousness from liberal to conservative. I discovered that a large number of working people — the very people the Left wanted to reach — were going to church instead of political meetings. Middle- and working-class Americans had a fundamental need for meaning and purpose that wasn’t being met by the Left.

When I tried to articulate that to a larger liberal community, I got nothing but hostility. I went to the leadership of the Democratic Party; I went to the leadership of the labor movement and the women’s movement and the civil-rights movement. Wherever I went, people reacted as if my goal were to subvert the Left and reintroduce sexism, racism, and homophobia — because that’s all they saw when they looked at religion. They simply had no notion of progressive or emancipatory spirituality.

Cooper: How do we integrate spirituality into traditionally secular institutions?

Lerner: In my book Spirit Matters, I describe what our educational, legal, economic, and healthcare systems could look like with a “new bottom line” of love and caring. Today courts are set up as a kind of arena in which two parties with opposing interests fight to the death. Imagine, if you would, a legal system in which the goal of lawyers was to serve the best interests of everyone involved — including society as a whole. The jury would be concerned with figuring out how to rectify all the distortions in the social fabric that had been uncovered in the process of hearing a specific case.

In economics, I’d like to see a Social Responsibility Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Corporations with incomes of over $30 million a year would have to get a new corporate charter every ten years, and they’d get one only if they could prove to a jury of ordinary citizens that they had a satisfactory record of social responsibility. People living in communities that were affected by the work and products of a corporation could bring evidence to show how socially responsible that company really was. It would suddenly become possible for decent people in corporations to do what they are now kept from doing: acting in the best interest of the human race. If such an amendment were passed, corporate leaders would be able to say to their investors, “I had no choice but to spend some of your money on socially responsible measures, because otherwise we might have lost our charter.”

As for education, nowhere have liberals more consistently missed the mark. They focus on better pay for teachers, upgrades to school buildings, and lower student-teacher ratios. All this is important. But then, in order to show that they are “tough-minded,” liberals have joined with conservatives to demand early and frequent “performance” tests to ensure that students acquire the necessary skills to succeed in the marketplace. The consequence of all this focus on material success is a population that thinks being smart means being selfish.

I’m advocating an educational system in which the goal is to create a person who is loving, alive to the spiritual and ethical dimensions of being, ecologically sensitive, self-determining, and creative. If that were the goal of liberal politics, it would win a lot more adherents than it does now, when it is seen as simply championing the special interests of the teachers’ unions. And the unions themselves should be at the forefront of “meaning-oriented” education.

Similarly, I want every social, political, and economic institution to be judged efficient, rational, or productive not only to the extent that it maximizes money or power, but also to the extent that it maximizes love and caring and fosters our capacity to respond to the universe with awe.

Cooper: Is this realistic?

Lerner: People hunger for love, for connection. They want their lives to be about something more than power and money. It may seem utopian, but before you dismiss the picture I’m painting, remember how utopian it seemed fifty years ago to talk about equality for women or African Americans. So it is with all transformations of consciousness: before they happen, everybody says they’re impossible; after they happen, everybody says they’re inevitable. Yesterday’s utopian visions can become the realities of tomorrow.