Here is what I remember most about the months I spent searching for dark matter: there are some things in the universe you can only find by looking away from them. It was how the professor who ran the lab greeted me on my first day, and I remember thinking, Yes, of course, and the thought was a revelation because this was a time when nothing about the world made sense to me. Later, sitting at my desk at midnight or nodding my way through some incomprehensible explanation, I would repeat the words to myself, trying to re-create that first frisson of . . . what? Joy, almost. Hope. The feeling that the universe itself was something I might take hold of if only I kept reaching. Even now, worlds away, the words have a certain magic to me.

I spent my days at the lab removing stars from vast pictures of the night sky. They were too bright, too loud, and they hid the smaller changes we were looking for: the slight gravitational warping that indicated the presence of dark matter. This was not my job, precisely. I was supposed to be constructing the two-point correlation function for certain galaxy clusters, but every time I thought I understood what this meant, it became immediately clear I did not. So I sat at my desk for ten or twelve hours at a stretch, using my mouse to draw lopsided red circles around problematic stars. At the desk next to me the other new research assistant was developing a computer program that we could feed my data into. We had our own corner of the lab, three computer screens each, and a nickname: the NASA girls. We were the only women.

Before we’d started, we’d emailed, proofread each other’s grant applications, discussed housing arrangements. I had imagined us as friends until our first day, when two things became clear: that for me a yearlong grant from NASA was an apex, and for her it was only a stepping stone. She was the real thing. She had the sort of brilliance I was only pretending to have. I think she understood this as well as I did, which I both respected and resented. No matter how many times I told her to call me Raffi, she kept reverting to Raphaela, which was the name of my great-grandmother who’d died in a concentration camp. Nobody called me that. My fellow research assistant had dark, greasy hair that fell to her shoulders and a perfect white center part. When she spoke, I stared at the part and willed her to run her fingers through her hair. She never did.

After staying as long as physically possible at the lab each day, I walked twelve blocks back to the sprawling, decrepit house where I lived with most of a men’s intramural rugby team. The room I rented was in the attic and half the price of anywhere else I’d found. It had a single narrow window and sloping ceilings that I crashed into once or twice each day.

Up there with me was a curly-haired rugby boy named Graham, who had a new injury each time I saw him: a split lip, ragged stitches beneath one eye, a wrist so swollen it hurt to look at it. He seemed too delicate for such a violent sport, but I knew violence was not proportional to mass, latent as it was in something as small as an atom. He’d grown up in northern Montana, where I had family. This coincidence, along with his immediate and unflagging belief that my job meant I was a genius, created a bond between us. We slipped into a strange domestic orbit in spite of our lack of similarity, in spite of my boyfriend, Caleb, who was working at a start-up across the country, and in spite of Graham’s girlfriend, whom I’d met briefly when she’d helped him move into the house. She’d worn cowboy boots and a flannel, had the sort of walk that made boys whistle. I measured myself against her and found myself lacking, which made it more satisfying when Graham ignored her calls so we could finish dinner.

Our intimacy was not physical, or was no more physical than the way our shoulders tilted together as we watched terrible movies on the couch late at night, or the way he sometimes fell asleep with his head resting against my thigh. Our intimacy was two children playing house. The way he paid for our groceries with cash he’d stockpiled in his sock drawer from selling weed, waving off my gestures of refusal — though in reality I was perpetually a paycheck away from overdrawing my bank account. The way he had water boiling on the stove when I got home from the lab. The way I tilted the cheap box of pasta into the water without a word. We ate straight from the pot, so as not to create more dirty dishes. Our intimacy was forks occasionally clinking together, flecks of pasta sauce staining our clothes.

Our intimacy was, above all else, the mutual willingness to see only the best in one another. “It’s a shame you don’t want kids,” he said to me once. As if my DNA were so valuable that not passing it on was some kind of loss for the world.

The job at the lab was a doorway, a wormhole to the life I wanted: acceptance into a PhD program, a prestigious postdoc, research papers, and discoveries about the inner workings of the universe. I’d gotten it by pretending I’d worked through all my difficulties with physics — a lie I still hovered on the edge of believing. I’d emailed the professor who supervised the lab and begged him to take a chance on me. True, my college transcript was unimpressive, but what I lacked in pedigree and proof I tried to make up for with conviction. Dear Professor, I’d written, then listed all the extra math courses I’d taken to give myself the necessary background for rigorous research. This research, I told him, was what I wanted to do with my life, and I would put in whatever work was necessary. Even in spaces less public than emails, even in the dark corners of my brain that admitted no visitors, I held entirely to this rhetoric.

When I wasn’t pretending to be an astrophysicist or a housewife, I was hanging around a sculptor named B, pretending to be an artist. I’d come across B’s work in an art gallery on one of my first days in the city and recognized their name from my high-school yearbook. Coincidences in those months felt significant — how could they not when my work was tracking the ways in which seemingly random alignments were proof of invisible structure? I asked the gallery owner for B’s business card, then sent an email before I could convince myself not to. I think we might have gone to the same school, I wrote. I came across one of your sculptures, the one where the girl is breaking open her rib cage and inside there’s a whole galaxy. I can’t stop thinking about it. I told them about my research at the lab — that it felt connected, somehow, to their art. I hadn’t started work yet; I was living in a universe where anything was possible.

We met at a coffee shop that served their lattes deconstructed on wooden boards: a shot glass of espresso, a tiny pitcher of steamed milk, a vial of lavender or hibiscus or cardamom essence. “So you’re a physicist,” B said. “That’s cool.” Half their hair was shaved off, the other half long. Graceful tattooed lines crisscrossed one arm. For an instant I imagined telling them how deeply miserable physics made me, as if I could tie us together with a confession.

“You’re an artist,” I said instead. “That’s cooler.”

“It’s not like physics,” they said. “If you want to make art, you can just do it. Come by my studio sometime, I’ll show you.” I would’ve done anything to spend more time with them, except ask.

And then, of course, there were the other days: the days I didn’t go to the lab or to B’s studio, the days I spent lying in bed, the weight of all the bones in my body insurmountable. My personal gravity had become erratic. I hadn’t figured out the formulae that would let me predict its rhythms, so I woke each morning with a sense of foreboding and waited to see how difficult it would be to lift myself from the bed. I was getting heavier as the months at the lab passed. Not larger, just denser, so that remaining upright required tremendous effort. I began to look longingly at sidewalks while walking the twelve blocks to the lab, imagining what a relief it would be to stretch my body out on the ground and sleep. One day I took a different route than usual and came upon a stone bench beneath a tree. Just for a moment, I told myself, and woke up hours later, my spine aching from the press of slate.

I called Caleb, who said, “I’m at work. Are you OK?” I explained about my fluctuating gravity. “What are you talking about? And shouldn’t you be at the lab?”

“It’s the dark matter,” I said. “Inside me.”

“I think you should talk to a therapist,” he said, not for the first time. “But I’ve got to go. I have a design that needs to be filed by noon.”

Caleb and I had met in the fall of my sophomore year, during a period I remember as a brief flicker of light. For once, my physics and math classes were going well. Understanding them made me feel invincible. On the weekends I let a friend drag me to the campus dive bar, where a library card could function as a fake ID, and I temporarily became a person who would go out on Sunday night. A girl who boys like Caleb bought drinks for at bars. By spring the illusion had dissolved. I couldn’t understand anything. I was failing to prove to myself whatever it was I needed to prove. Some part of me was convinced that Caleb never forgave me for that initial well-being, the way it tricked him into thinking I was someone who knew how to be happy.

At the studio with B I tried to sculpt my heaviness, but it only looked like a lump of clay. I imagined asking them how to sculpt a black hole, the deepest gravity, exhaustion that eats whole days. I imagined their hands on top of mine, crushing the clay until it was dense enough to warp the weave of space-time. In theory, any mass could become a black hole if it was compressed tightly enough. In theory, inside a black hole space might flow like time and time might stretch like space and the law of causality might become mere suggestion.

Across the room, B knelt next to a statue of a horse that was so lifelike I kept startling at the sight of it. A girl was draped across the horse’s back, her body seeming to melt into the horse’s. B was using what looked like a scalpel to carve detail into one of the horse’s hooves. They were wearing overalls with a sports bra and no shoes, though the floor was littered with scraps of clay and plaster. They had their bottom lip pinned under an incisor, hair messily plaited down one side of their head. I tried to bite my lip identically, remembering studies that showed forcing a smile could induce happiness. If I could mimic B’s expression, maybe I’d feel whatever it was they were feeling. But all I felt was tired.

I was still moving my mouth in weird ways when they looked over. They raised an eyebrow, held my gaze for two heartbeats that I heard in my ears, then turned back to their work with a half smile. I looked down at my hands. I’d squashed my black hole; the clay was squeezing from between my fingers. It was an improvement.

At the lab I was largely left to my own devices, and I wondered if my bewilderment was perceptible, measurable in my endless red circles. I had thought nobody understood dark matter — that it was, fundamentally, an encapsulation of all we didn’t know. But it turned out other people’s lack of understanding took the form of complex theories, mathematical equations, computer programs that turned impenetrable data into different impenetrable data. Other people’s confusion was a castle you could live inside, a whole architecture of the unknown. My confusion was a wall I kept walking into.

Once, at the lab, I called dark matter “hypothetical,” and the professor said, “I might be biased, but I think hypothetical is a little much. We can measure its effect. We can detect it astrophysically. We just haven’t identified it in the lab yet.” After that, I tried to avoid calling dark matter anything at all.

Another evening, the professor stood behind me, watching me circle stars. “Don’t feel pressured to do all the data cleaning yourself. We have undergrads who help with that sort of thing,” he said. I told him I didn’t mind, that I enjoyed working with the raw data, that I found the pictures of the sky inspiring. I had no idea what I was saying, but he smiled. “I know exactly what you mean,” he said.

I had time before I had to present my research. I had time in which anything might happen.

When I felt particularly despairing about work, I let Graham and the rugby boys drag me to the nearest bar. Anytime my glass of beer started to empty, they filled it from a pitcher. Soon my head was buoyant, though the rest of me stayed earthbound. This had always been the sort of belonging I’d found easiest to come by: not one of the boys, but not exactly a girl, either. When a boy from another table tried to talk with me, the rugby boys puffed their chests out and chased him away, tripping over one another to defend me. “Fuck off,” they said. “Raffi doesn’t go home with strangers. She’s not like that.”

What was I like, I wondered. How could these boys — these drunk and happy people I barely knew — have the answer? I ought to have been annoyed, but instead I was grateful. I was too tired to talk, too tired to pretend to be anything. Whoever the rugby boys thought I was, they seemed to like her. I tried to imagine what B would think if they were here, but they would never have come here. I let the rugby boys take turns piggybacking me home.

Caleb and I communicated mostly via email, a fact I didn’t let myself interrogate too deeply. Often, by the time he left work, it was late enough that I could plausibly have been sleeping. Caleb’s emails told me about the marathon he was training for, and the office dog named Bernard who had his own line of raincoats. Mine were mostly run-on sentences about how I would never understand anything and what was the point of trying so hard. I often regretted the emails as soon as I’d hit send.

You’re doing this to yourself, he wrote back. Why are you so determined to do something that makes you miserable?

Dear Caleb, I wrote, what could be more worth making oneself miserable over than understanding the whole universe?

It was late in the afternoon on a Saturday, and I was lying on my twin-size mattress on the floor, staring at the peeling paint on the ceiling. I had been half asleep when his email had come, but now I felt an electric current running through me, propelling me into a sitting position.

Dear Caleb, I need to prove to myself that I’m capable of anything if I work hard enough.

Dear Caleb, maybe I’m incapable of being happy but what does that matter if I can be a genius?

Dear Caleb, why does genius always belong to men?

Dear Caleb, maybe if I understand dark matter and the night sky, I will also understand how to get out of bed in the morning.

Dear Caleb. Dear Caleb. I deleted all my replies, the electricity draining out of me.

I felt certain Caleb wouldn’t leave me (if he was going to, he already would have) but also that he loved only parts of me. I loved him like my left hand: not something I’d compose odes to, but difficult to imagine life without. I’d struggle to tie my shoes or chop an onion one-handed. But I would still be able to make circles around stars.

The days I woke to find myself weightless were rare enough that I wished I could hoard them, bind them like atoms into some new molecule — an effortless week, a bearable life. Since I couldn’t, I tried to shield them from contamination. So when I woke one morning, hours before my alarm with my mind crisp and clear, I ignored the urge to head to the lab. Instead I texted B, the only person I trusted not to ruin it. Breakfast? I asked. When I arrived at the diner nearby, they were sitting in a corner booth, hands wrapped around an enormous mug. They’d died their hair magenta.

“You’re vibrant this morning,” they said. I thought of Caleb, who’d once said to me, “You’re luminous. I love you when you’re like this.” How all I could hear was the inverse: I don’t love you when you’re not.

I ordered pumpkin pancakes and asked B about their sculpture. “I keep seeing it, but I never want to interrupt your work to ask,” I said. I was talking too fast. I stole their cup of coffee and took a sip to stop myself.

They told me that even though their family didn’t have money, they’d had a horse as a kid, that being around her had eased a deep loneliness. Their face went soft. “I think we overlook the importance of nonhuman relationships,” they said. “The grief I felt when she died . . . I’ve never felt like that for a human. It was as though she was a part of me, like being with her expanded — or maybe dissolved? — the boundaries of what I considered to be myself. That’s the feeling I’m trying to capture in the piece.”

They wanted to hear about my work in return, and I told them how some invisible thing was changing the behavior of galaxies, making them spin together instead of fly apart. I explained about searching for gravitational distortion, and how it was impossible to tell from a singular piece of data whether something was distorted. “Distortion is a matter of relation,” I said, talking too fast again, but B smiled. After breakfast they walked me to the lab, their arm looped through mine as if it were nothing.

Inside the lab, computers were humming and keyboards were clicking and I could feel the weightlessness seeping out of me. The professor told me I’d done good work on a write-up I’d sent him the week before. It occurred to me that perhaps he meant it. I had spent so many years worrying about someone realizing I was a fraud. For the first time I considered the opposite: That my confusion might remain hypothetical, unidentified. That I might be able to spend the rest of my life sitting at this desk, wishing for the lightness of nonexistence.

Sometimes B invited me to things: a gallery opening, a poetry reading. I always said yes, though I wondered if I ought to say no periodically to make it seem like I had a life. But I didn’t reciprocate. What would I invite them to? Nights out drinking with the rugby boys? I was a different self around each of the people in my life, and the selves were mutually exclusive.

One night we went to a lecture called “Impossible Design” by B’s favorite architect. The auditorium was crowded, the introduction effusive. The architect was a woman in her late thirties with close-cropped silver hair. “Who decides what is possible?” the architect asked, standing on stage in a corona of light. “It’s tempting to frame possibility as an objective characteristic. The laws of physics, a teacher of mine once said, tell us as architects what we can and cannot do.”

I felt B smile at me; I was holding my breath.

“But that is an oversimplification. Possibility is always changing. New materials are developed that are stronger, lighter. Advancing technology allows us to test designs with increasing accuracy. Possibility is not objective, in other words. It is imagined. And the question of whose imagination we attend to is a deeply political one.”

After the lecture, B was effervescent. Outside, the air was cool and damp, the wind whipping leaves into gyres. “Isn’t she incredible?” B asked.

I nodded, wanting to match their enthusiasm, but what I felt was a specific, habitual despair: a recognition of brilliance that was inextricably linked to an understanding of my own deficiency.

“Is it true what she said about there being a nonzero chance of a ball going through a wall each time you throw it?”

“Technically,” I said, “I guess. I think she’s talking about quantum tunneling.”

“Can you give me the lay-sculptor’s version?”

I tried to come up with an explanation, but all I could think of was an old physics professor of mine who, when I’d suggested writing my senior thesis on the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, had said, “The general public hears ‘multiple universes’ and forms ridiculous notions of alternate lives, but we’re here for real science, not science fiction. Better leave interpretation to the philosophers.”

“Raffi?” B said. “Are you OK?”

“I can’t explain quantum tunneling.” I was crying, which horrified me.

“That’s fine,” they said, their voice gentled the way I imagined it might be for a spooked horse.

“I can’t understand anything,” I said. “I’m failing.”

“You’re doing research for NASA.”

In a sense this job was what I’d always wanted: indisputable proof of my own capability. But maybe evidence could be both indisputable and wrong.

“I barely made it through undergrad.”

“What does ‘barely made it through’ mean? That you got B’s?” They laughed when I didn’t reply. I couldn’t explain it, or I wasn’t willing to try. Maybe somewhere there was a universe where I’d said hello to B when they were still the kid draped over their horse’s back, a universe where we knew each other so well there was no need for explanation.

B offered to walk me home, but I told them I was fine. Once I was far enough that they couldn’t see me, I called Caleb, but then I realized I had nothing to say. I had never mentioned B to him. “What’s up?” he asked. “What’s wrong?”

“The leaves are changing,” I said, “and my chest aches.” The conversation was soon more pause than talk, and he had to run, goodbye, talk later.

When I got home, Graham was drunk and looking for his car keys. They were sitting in plain sight, but rather than point them out, I slid them into my pocket. He told me he’d agreed to meet up with a woman who’d given him her number at the bar. I didn’t say, What about your girlfriend? I didn’t say, What about me? I waited for him to notice my quiet. He filled the silence, didn’t look at my face, didn’t ask what was wrong. I thought about keeping his keys hidden — out of hope or vindictiveness, I wasn’t sure — but when he stumbled over to me, I held them up. “I’ll drive you.”

His car was new and expensive, and I drove ten miles under the speed limit. When we got to the house, he wrapped his arms around me, then disappeared. Was there a universe where our intimacy was more than charade?

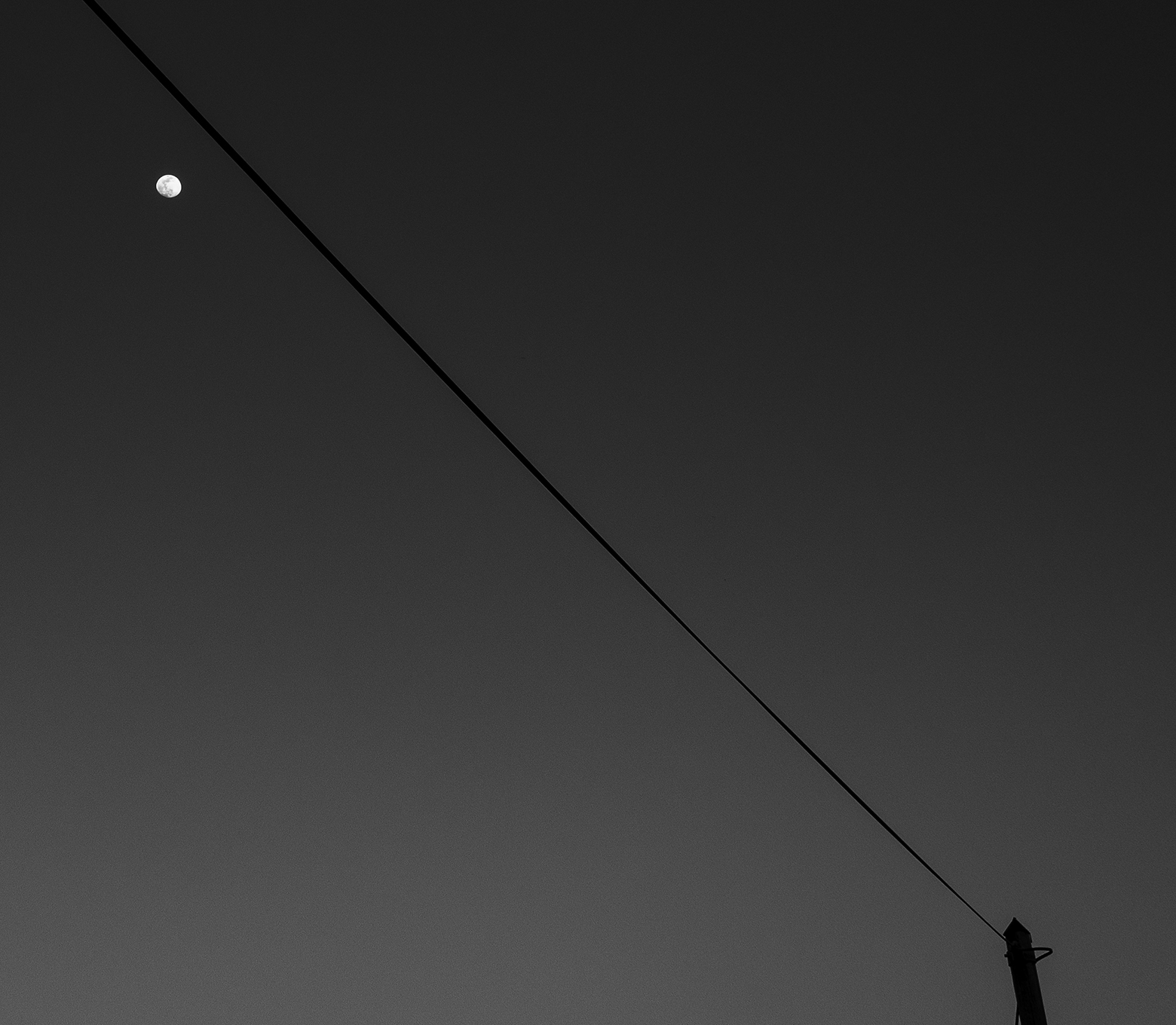

Falling asleep was often a prolonged game of cat and mouse, but one night I closed my eyes straight into sleep. When I opened them, I was sitting on the sand next to a pale-pink lake. The sky was a dome that darkened from azure to cobalt, nothing like the flat-black images I’d spent the summer staring at. The Milky Way was a pearlescent seam knotting the heavens together, the moon so bright it ought to have overshadowed the stars, but they seemed content to coexist. I lay back on the sand and circled the North Star with my finger.

“Are you going to delete her?” a voice asked, and when I turned my head, there was B lying next to me, our shoulders pressed together.

“No,” I said. “I won’t delete a single one.” I felt a certainty that was entirely unfamiliar, and I closed my eyes into the relief of it. When I opened them, the stars were still there, but the moon was gone. I looked down, and it was in the palm of my hand: a ball of clay. Looking at it felt like falling in love with the whole world.

When I woke, I was crying. I stared at the ceiling until the room became light, trying to remember if I’d ever felt a happiness like that in my waking life.

Here is what I know about dark matter: It holds galaxies together. Or, at least, galaxies hold themselves together, and we don’t know why. Dark matter is the answer to a problem, the implication of an equation. Dark matter deforms space-time so that light from distant stars bends and haloes. Or space-time is deformed, therefore we know something is there. Dark matter is not dark; it is invisible, inaudible. It is the transparent scaffolding for our luminous universe. Or maybe dark matter doesn’t exist at all. Maybe there’s another solution to the equation, just waiting for someone to think of it. But that someone would not be me.

I came up with better reasons than a dream to leave the lab. I knew how these stories were meant to go, life arranged like a math proof, each moment leading to the next: a perfect, irrefutable chain. But I have studied the physics and philosophy of time, and it is neither a river nor an arrow. Time is a dimension, and our lives stretch across it, each of us a four-dimensional shape taking up some small space in the universe. All moments existing at once and forever.

I circled a final star. I didn’t answer B’s messages asking if I was OK. I tried to explain my decision to Caleb but failed, so I stopped trying. I made plans to go stay with a friend, packed up my room at the rugby house, let Graham carry my bags downstairs. I would never see him again, nor the professor, nor B, though for years I would think of writing them.

Dear B, even now I can close my eyes and see your thumbs shaping the hollows of a horse’s skull.

Dear B, have you ever felt one dream shiver straight through the center of another? Gone to sleep in a familiar universe and woken up somewhere new?

Dear B, I have left real science behind and turned my attention to matters of interpretation.

Dear B, it still hurts me to think about my failure. Maybe that’s why I can’t bring myself to write to you.

Dear B, a professor once told me there are some things in the universe you can only find by looking away from them.

Isn’t that a beautiful, ridiculous thing to say?