I came to believe early in life that worrying would ward off disaster and pain, even though it often didn’t.

When I was eighteen, my first love got drunk at a party and screwed some guy she didn’t know. She told me about it in bed a week later and said she was sorry. It hurt so bad I wanted to die. With every new girlfriend after that, I worried this might happen again. And it did, over and over, like some kind of self-fulfilling prophecy.

My bad habit of worrying serves me well at work, though. As a wilderness firefighter, I’ve learned to ask myself throughout the workday, “What could kill me now?” But, as a salty old firefighter once told me, “Expecting the worst is a great way to fight a fire, but it’s a terrible way to live a life.”

I stopped worrying only when life got really bad. In the span of a year and a half I broke my hip in a parachuting accident, my mom was diagnosed with terminal cancer, and my girlfriend died in a helicopter crash. There was no way to prepare for or guard against this pain, which hit me full force. I got to see for myself that real pain, deeply felt, is nothing to fear.

L.B.

Eugene, Oregon

Between the ages of seven and nine I experienced a lot of changes in my life: My parents divorced, and my mother moved down the road to live with her boyfriend. My father remarried and began having children with his new wife. My sisters started sneaking off to meet boys. I found solace in sweets. Once a scrawny, scrape-kneed kid, I ballooned into a stringy-haired, tubby girl with thick glasses.

My sisters were both thin, athletic, popular, and talented, but our mother was the thinnest and fairest of the women in our family. She began chasing her youth, wearing skintight bodysuits (no bra), flowing Indian-print skirts with tiny bells along the hem, and turquoise-and-silver jewelry. Mom called me Pumpkin and offered to buy me a new wardrobe if I would just lose some of that “baby fat.”

I had no boyfriends — not even a boy who was a friend. I envied my mother and sisters, though all three of them were often unhappy. My oldest sister struggled with bulimia, and the other numbed her pain with alcohol. Our mother attempted suicide several times. I would sit eating Girl Scout cookies and silently watch these women. Eventually I saw the danger of their compulsion to be thin, feminine, sexual. I grew determined not to compete. I ate instead. Fat equaled nonsexual equaled safe.

I grew up and got married. Sam and I had been together for twenty years when, during a conversation with friends about weight and diets, I confidently stated that I had never had any dramatic weight gains or losses. Indeed I had stayed about the same weight for my entire marriage. I looked to Sam, who was innocently reading his paper, for affirmation. He averted his eyes.

OK, I had gained a little weight: about three pounds each year . . . for fifteen years.

I was voluptuous, plump, chubby, fat. And safe.

A few years later my oldest sister and her twelve-year-old daughter joined me at a cafe on a sunny spring day. My niece, who looked much like I had at her age, was refusing to take a bite of the pastry her mother offered. Exasperated, my sister asked me to talk to her daughter and tell her one bite wouldn’t hurt.

I took a final mouthful of my triple-chocolate-glazed, cream-stuffed tart and washed it down with a swallow of my grande double mocha. Then I sat forward, belly bulges folding neatly over one another, and told my sister that I knew she hadn’t intended to hurt my feelings, but what she had asked me to do sounded to my ears like You’re fat. Tell my daughter it’s not that bad.

My sister turned red and protested that I had never seemed bothered by my weight: I was so happy and outgoing and wore such colorful clothes.

“I am not happy,” I replied. “I just prefer to be known as ‘the outgoing woman with the colorful clothes,’ rather than ‘the fat woman with glasses.’ ”

J.C.

Portsmouth, New Hampshire

By the time I was four, my parents were desperate to get me to stop sucking my thumb. They bribed me with candy and an Easy-Bake Oven. They enlisted my extended family’s help: Aunt Rose clucked her tongue and shook her head, warning I would ruin my teeth. My grandfather threatened to cut off my thumb. But this only motivated me to hide my habit more carefully.

On my first day of kindergarten, during a sleepy moment, I slipped my thumb into my mouth, and the other kids pointed and laughed. Still, I didn’t stop completely. I just waited until I was safely tucked into bed to suck my thumb again.

Through grade school, junior high, and high school, this habit was my shameful little secret. My teeth remained perfectly straight, which is lucky, because nothing but thumb-sucking gave me a respite from the pressures of adolescence.

Now, as an adult, I do it only during times of severe stress or sadness. My old habit still proves incredibly comforting. (My husband knows about it and thinks it’s adorable.)

I am a psychotherapist and work with people who struggle with anxiety. Before coming to me, many of them used alcohol and pills to calm themselves. I don’t drink or use drugs — I’ve never had to. My thumb is always there to soothe me. Maybe my bad habit isn’t so bad after all.

Name Withheld

I’m not going to list all my bad habits here (one is that I’m reluctant to share), but I will mention my favorite: hypocrisy.

I often claim virtues I don’t have — or want — and judge others for not having them. I admit few sins of my own while counseling friends about theirs, which are many and severe. Those who are truly virtuous tend to get on my nerves.

The highest form of hypocrisy is hating the hypocrisy of others, and I do judge my fellow hypocrites. As an ordained pastor with advanced theological degrees and years of spotty service, I can speak expertly on the hypocrisy of the Southern Protestant clergy. In the pre–Civil War South many pastors defended slavery and cited biblical justification for it. Later, Jim Crow laws had the full support of most Southern Protestant pastors. Too many also endorsed the oppression of women — at least, until women became baptized by immersion in the workforce and had enough money to pay tithes and give offerings. Too many Southern pastors have preached the limitless love of God but been clear that it does not extend to homosexuals. Too many of us preach about Christians being strangers in a strange land and then offer to chip in to build a wall to keep other strangers out of the land in which we live. Too many of us preach about Jesus the Great Physician and then advocate rationing healthcare based on one’s ability to pay. Too many of us preach about Jesus the Prince of Peace and then support every war our country wages. Too many preach about the miracle of the loaves and fishes and then ignore the problem of food insecurity for American children.

Who can blame us? We all want to keep our jobs, our health insurance, and our retirement programs. Jesus said, “Blessed are the poor,” but no one in his or her right mind wants to join them. The gospel of Christ calls for selling one’s worldly goods to meet the needs of others. It calls for dropping the sword and loving one’s enemy. It calls for touching the leper and bringing the homeless into our homes. If the pastor of a conservative congregation were to preach the gospel of Christ as it is presented in the New Testament, that preacher would likely become unemployed. Hypocrisy is the only solution for any pastor with a keen sense of self-preservation.

I wear my hypocrisy much the way a police officer wears a bulletproof vest: It protects me from others. It protects me from myself. I am the laughing clown who struggles with depression. I wear a mask of concern, even when I can barely break through the armor of indifference. I am passionate about important issues but have long since resigned myself to not making a difference. I would love to be the man I appear to be, the man I pretend to be, but the truth is I am not even close. The truth is, that man would get on my nerves.

Doy Daniels

Milan, Tennessee

When I was about three years old, I developed a painful stomachache and began vomiting after every meal. Our family doctor came to the house to examine me. That evening my mother wrapped me in my favorite purple blanket, handed me my stuffed monkey, and told me we were going to spend the night with my grandmother. Instead we went to the hospital, where I had my appendix removed.

Although my mother’s intentions were good, I was confused and upset by her lie. I felt as if the appendicitis were a punishment for something I’d done.

As I got older, I continued to spot differences between what my mother said and what I knew to be true, and I began to mistrust her and call her out on her dishonesty.

By high school I was always jumping on the lies and hypocrisies of others. I was committed to being honest about everyone’s mistakes and bad behaviors, and I didn’t give much thought to anyone’s feelings or the consequences of my words. In fact, I felt justified in setting the record straight. I honestly thought I was doing people a favor by letting them know the “truth.” As you might imagine, I alienated just about everyone.

A long time would pass before I could own up to the motives behind my aggressive criticism of others. I had to admit that my truth-telling was just as hurtful as my mother’s lies had been. Now I work to keep my mouth shut and simply listen. If people want my opinion, I remind myself, they will let me know.

Roberta Floden

Forest Knolls, California

It’s 3:30 in the morning, and I’m fixing a hit of speed mixed with heroin. I enjoy the conflicting highs I get from taking these drugs together: the euphoric rush from the speed taking me up, up, only for the heroin to intercept my flight and bring me back down to earth, over and over. Absolute nirvana.

There are six other people here at T.’s, all addicts who’ve come to purchase drugs. T. is a friend of mine, but he has a reputation for violence. Touching anything in his house is forbidden. The consequences for violating this rule are generally a punch to the face, followed by a series of vicious kicks as the offender curls into a fetal position on the floor and tries to apologize. Many times I’ve seen T. grab the nearest object and pummel a person with it. But he happens to have some of the best speed around, so most of us overlook his brutal tendencies.

Right now T. is engaged in a serious dice game with a woman whose name I forget. Tammy? Sandy? Something that ends in a y. Elsewhere in the room two attractive women are sharing a recliner and kissing passionately, their hands down each other’s pants. Two more people, whose names I’ve never bothered to learn, are in the bathroom smoking speed and inspecting their faces in the mirror — typical speed-freak behavior. Either they think they can find the answers to the universe in the pores of their skin, or they are trying, with torturous pushing and squeezing, to exorcise the demons they believe are embedded there. I’ve never done this myself, but who knows? Perhaps the demons in my skin are just waiting for the right moment to strike. I don’t even shave while I’m high, for fear the razor will raise some bump or irritation that I will feel compelled to battle for hours in a brightly lit bathroom.

Shivering with this thought, I depress the plunger and push the drugs through the needle and into my vein. And in the fraction of a second before the speed and heroin begin their battle for supremacy in my central nervous system, I think maybe I should kick this habit.

Christopher R. Lanteigne

Crescent City, California

When a job application asks me to list my strengths, I put down hardworking, responsible, reliable — all true. I also write punctual.

This is a fabrication. When hired, I strive to be on time for as long as possible, but about two or three weeks in, my employer suddenly notices that I am habitually late. By then, hopefully, I’ve completed a good amount of training, and my bosses will decide they’re stuck with me.

I have become a master at making excuses for being late: my car wouldn’t start, my alarm clock didn’t go off, my dog went outside to relieve himself and wouldn’t come back.

Friends and family, tired of waiting for me to show up, have started giving me false meeting times. They will tell me the plan is to meet at 4:00 PM when the actual time is 4:30. If I show up before 4:30, I get a taste of my own medicine. (This has rarely happened.) Other, more understanding, friends simply bring a book to read while they wait for me.

I am aware that my bad habit makes me seem selfish and disrespectful of people’s time, but those aren’t the reasons I am late. I’m late because I struggle with obsessive-compulsive disorder, which causes me to engage in repetitive behaviors when I should be walking out the door. My OCD isn’t something I like to talk about, so instead of telling my bosses and friends that I have a mental disorder, I lie and make excuses. Though I’m learning to live with and accept my OCD, on some level I am still ashamed of it.

Jennifer Reiten

Superior, Wisconsin

When I rescue stray cats, I believe I’m doing a good thing, but my husband thinks it’s a bad habit. “You can’t save them all,” he says.

He’s right. But I know I can save this one.

Rosie and Emmett, Skky and Odie, Baxter and Murphy, Jake and Bennie. Was it wrong to take them all in? One always sits beside me as I write, another when I eat.

In the morning when I wake, I make eggs for Murphy, tuna for Emmett and Baxter, milk for Odie, coffee for me. The cats are getting on in age — the oldest is ninety-three in people years — and have become quite picky about what they eat. I give them whatever they want. What could it hurt?

At night my bed is full, with Baxter on my pillow, Odie at my chest, Emmett tucked behind my knees, and Murphy warming my feet. They sometimes keep me up, but I’m never cold. Or lonely.

Perhaps if I got a larger bed, all the animals would fit.

“Oh, no you don’t,” says my husband.

What if I got rid of him? I’d have plenty of room then. If he would sleep in the garage or next door, I could squeeze in two or three more. Of course, I wouldn’t really do this. Would I?

Marcia Hage

Kelsey, Minnesota

After my last relationship ended, I fell back into my bad habits as if falling into bed after a long day. Dishes piled up in the sink; candy wrappers littered my desk; mounds of unopened mail grew into mountains. I smoked. I drank alone. I ate junk food. The TV blared constantly. Two years passed.

Then I met her.

I won’t go into detail about how beautiful and amazing she is. Let’s just say I fell for her, and I knew I had to win her heart, which wasn’t going to be easy; she was out of my league. But when I looked at her, I felt my hopes rise like the sun. I had to change my life, break my bad habits, and prove myself.

I began writing poems and songs again. I jogged for my health and for the joy of it. I smoked less, drank less, worked harder, gave more to friends and strangers. I flossed my teeth so often my dentist noticed. New songs flowed from my guitar. I could do anything as long as I was driven by the hope that she might notice me. And within a year she did.

The good habits I developed helped me in other ways, too. I was asked to present at a conference and to give a poetry reading. My circle of friends expanded. I played shows with my band and sang with a confidence I had never felt before. People remarked on how happy I seemed, how well I was doing.

Slowly she and I became friends and began exchanging e-mails. We met for coffee, then lunch, then drinks. I gave her small tokens: books, stones, a pair of earrings.

Even when the rebuffs began — an e-mail unanswered, a planned dinner changed to a quick drink — I held on to the hope that some moment we shared might cause her heart to open. I worked harder on myself: doing benefits for charities, helping old ladies carry packages to their car, practicing kindness. I wrote to her more often. She was always sweet but maintained a careful distance.

The ending, of course, is predictable. In her graceful way she made it clear she wasn’t interested. No change I can make, no habit I can break will make her love me.

She is now seeing someone else, but I still clean my breakfast dishes and sweep the floor, thinking if only she could see this place, if only she knew me better, if only I wrote something worthwhile . . .

In the past two years I have broken many bad habits and done many things I never would have done otherwise. And my life is richer for it.

Now I have only one bad habit left to break.

Ken Zimmerman

Eugene, Oregon

First I open up a couple of napkins and place them on the counter. Then I take a bite of cake, chew, and spit it onto the napkin. I continue until the cake is all chewed.

Why do I do this? It’s time-consuming. It’s a waste of money. It’s bad for my teeth. But I’ve been doing it for years because it relieves stress. I suppose it’s comparable to smoking cigarettes, or maybe not. I’ve never been a smoker.

Sometimes, as I’m chewing and spitting, I contemplate my guilt over saying the wrong thing to my son, or my anxiety about money, or the sorrow I still feel many years after the dissolution of my marriage. Does my habit help? I’m not sure.

It’s so habitual that I sometimes do it in public. Other people do not notice — I think — but I feel ashamed anyway. If someone asked, “Are you spitting out your food?” I would probably lie. I mostly chew and spit sweets, because I find it hard to control myself in their presence. Sometimes I go home with a bag of cookies and stand at the kitchen counter chewing, getting the taste, and then spitting them out. I don’t want to be fat. I swallow only healthy food, for the most part.

Do I do this because of the grief that I still feel over the death of my sister when I was three? Is it my lack of self-worth? My shortcomings as a mother, as an artist, as a human?

I want to stop. Some mornings I’ll wake up and wonder, Is this the day I won’t want to do it anymore? But I also fear that if I stop, I won’t be able to start again. And then where will I be? Hungry? Sad? Depleted? Empty?

Name Withheld

When I was seven, my best friend and I stole a pack of Marlboros from his mom, snuck off into the woods, and puffed on the cigarettes (we didn’t dare inhale), gesturing and posturing like cool teenagers. They tasted terrible, and we soon decided to do something else. But I pocketed the rest of the pack.

Not long after that, I went through a brief pyromania phase. I’d set small fires in dry leaves or trash and stomp out the flames before they got too big. Then a grass fire nearly got away from me, and I quit lighting them.

In school I was frequently sent to the principal’s office for mocking teachers, telling dirty jokes, and being generally disruptive. Corporal punishment was the norm back then, and I eventually decided that being the class clown wasn’t worth getting paddled all the time. I also learned I could get away with a lot more if I didn’t draw attention to myself.

I became a quiet and respectful student who made good grades. By the age of fourteen I was also a pack-a-day smoker and a pothead. I began experimenting with PCP, LSD, and assorted pills. Still, I maintained perfect attendance. Why skip school? That’s where the drugs were.

In college I smoked weed constantly and got drunk every night. I often drank in the mornings and even discreetly in class. I took massive doses of acid and mushrooms. My sexual partners were mostly strangers I met in bars or at parties: both women and men. It was not unusual for neither of us to recognize the other in the morning. I used speed and coke to fuel my nonstop partying and to help me cram for exams. Somehow I managed to graduate.

Over the next few decades I juggled addictions to alcohol and cocaine, prescription drugs and married women, methamphetamine and pornography, alcohol and heroin. A liar and a thief, I was often homeless and unemployable. I sold drugs but always lost money because I couldn’t stop dipping into my supply. I’ve lost count of how many times I went to treatment centers, psych wards, emergency rooms, and jails.

I never dreamed I’d reach the age of fifty-seven, but here I am. I’ve finally sobered up and settled down. My bad habits are few and relatively tame.

But I still haven’t put down these goddamn cigarettes.

Kent H.

Chattanooga, Tennessee

I’m sorry.

I’m sorry I don’t have a better way to start this. I tried to think of an interesting hook or an amusing anecdote, but then I figured I might as well just get it out there: of all the bad habits I possess (and there are many), unnecessary apologies are the worst.

I’m sorry. It rolls off the tongue so mindlessly, like an um or er, I barely hear it anymore.

When I was a child, apologies were often expected, even demanded, of me, and I was a quick learner, eager to please and pacify. I’m sorry did the trick with angry parents and irritated teachers and bullying classmates. Even when I wasn’t at fault, peace was more appealing to me than justice. I’d do anything to dissipate the tension so I could go back to my books, my cats, my drawings, my imagination.

As a teen I felt like apologizing for my existence. I was too fat, too plain, too clumsy, too dreamy, too awkward to take up space in the world. Numbing myself with alcohol and drugs helped. So did angry music, art, dark clothes, dark hair, and friends who felt the same. I disappeared a little bit.

As a college student I began to see my privilege more clearly — not just as a white female but as a middle-class American with clean drinking water and access to birth control and a warm home and plenty of food. I was so lucky. And I was so sorry about it.

I’ve come to realize that I’m sorry is the wrong reaction to all of the above. I do not need to apologize for having an imperfect body. I do not need to apologize for my First World privileges (although I do need to work on making the playing field more even).

Yet I still mindlessly say, I’m sorry, dozens of times a day: To the clerk at the grocery store when I forget to bring a bag. To the waiter when I request my salad dressing on the side. To the postman who has to lug a big box to my doorstep. Even to my sweet boyfriend when we bump noses while kissing.

Recently I’ve started paying more attention to the men I know. Few of them seem to possess this verbal tic. What’s their secret? My five-year-old son has become my role model. Sure, he’ll say he’s sorry when he has hurt a friend’s feelings or carelessly broken a toy, but he never apologizes for his existence.

Jessica Kautz

Missoula, Montana

I saw him occasionally on the grounds of the garden where I volunteer. He always greeted me cheerfully, and we would talk about landscaping. I risked asking whether he was single. He was. At the holiday gathering in December we talked some more, and after he walked me to my car, I gave him my phone number.

Our first date went well until, as we were saying goodbye in the parking lot, he told me he was a sex offender. Then he turned and walked away.

When we met again a few days later, he told me the story of how he’d ended up in prison for his nonviolent offense and what he’d been doing in the two years or so since his release. He had decided to be completely transparent with people he met, he said, and he promised he would always do so with me.

If he could promise transparency, then how could I not? So I told him that I’d been a shoplifter since grade school. It started innocently with a plastic fishbowl decoration from the five-and-dime, then expanded to items like lip gloss. Stealing wasn’t pleasurable or exciting. I felt only terror as I left a store. Yet I did it again and again. I’d been unable to tell anyone this for decades. How could I explain what I couldn’t comprehend myself? Disclosing my secret to this man brought relief from years of shame.

Since revealing my secret, I haven’t shoplifted again, and the man and I are still together. I feel as if I’ve been offered another chance at life. I’m going to take it.

Name Withheld

I try not to get on Facebook too much, because once I do, I can’t seem to leave. And it’s not always a pleasant experience.

A few years ago I asked my adult daughter what was going on in her life, and she told me I should follow her on Facebook. So I joined and found out what she was doing, and then what my friends were doing, and then what people I’d known in elementary and high school were doing. It was exciting — at first.

I saw old friends traveling, getting married, having babies, celebrating anniversaries, redecorating their homes, dancing in ballets, showing their paintings in art galleries, and I thought, Wow, they have such amazing lives. . . . What’s wrong with me?

I forget sometimes that people share mostly their best moments, the events they want people to know about. They don’t post pictures of themselves sitting around depressed, watching dumb TV shows, having arguments about money, giving whiny children a timeout, or cleaning up after their dogs and cats.

I, too, try to present a sunny image on Facebook. One time I arrived in a foreign country alone and frightened and not sure I wanted to be there. I got on a hot, crowded tour bus and snapped photos of skyscrapers, ancient temples, and blue mountains. When I got back to my room, I posted the pictures on Facebook. Friends soon commented on what a cool trip I was taking. It made me feel good — for a minute. Then I saw I was being dishonest, portraying this trip as a happy one.

Another time I was reading through an acquaintance’s witty, carefree posts, and I thought her life must be a constant stream of happiness and joy. Then I ran into her a few hours later and discovered she was having a terrible day. She was taking a walk to try to ease her anxiety.

I’m sorry to say it made me happy to see her as an ordinary human being with problems like me.

Lynne Davis

Carbondale, Illinois

As a young man I sometimes masturbated four or five times a day. I worried this was too much, but it made me feel so good. There were times I had to stop because I had literally rubbed myself raw. I would look down at my wounded appendage and think, What have I done? Though I might stop touching myself for weeks, the moment I was healed, I was back at it.

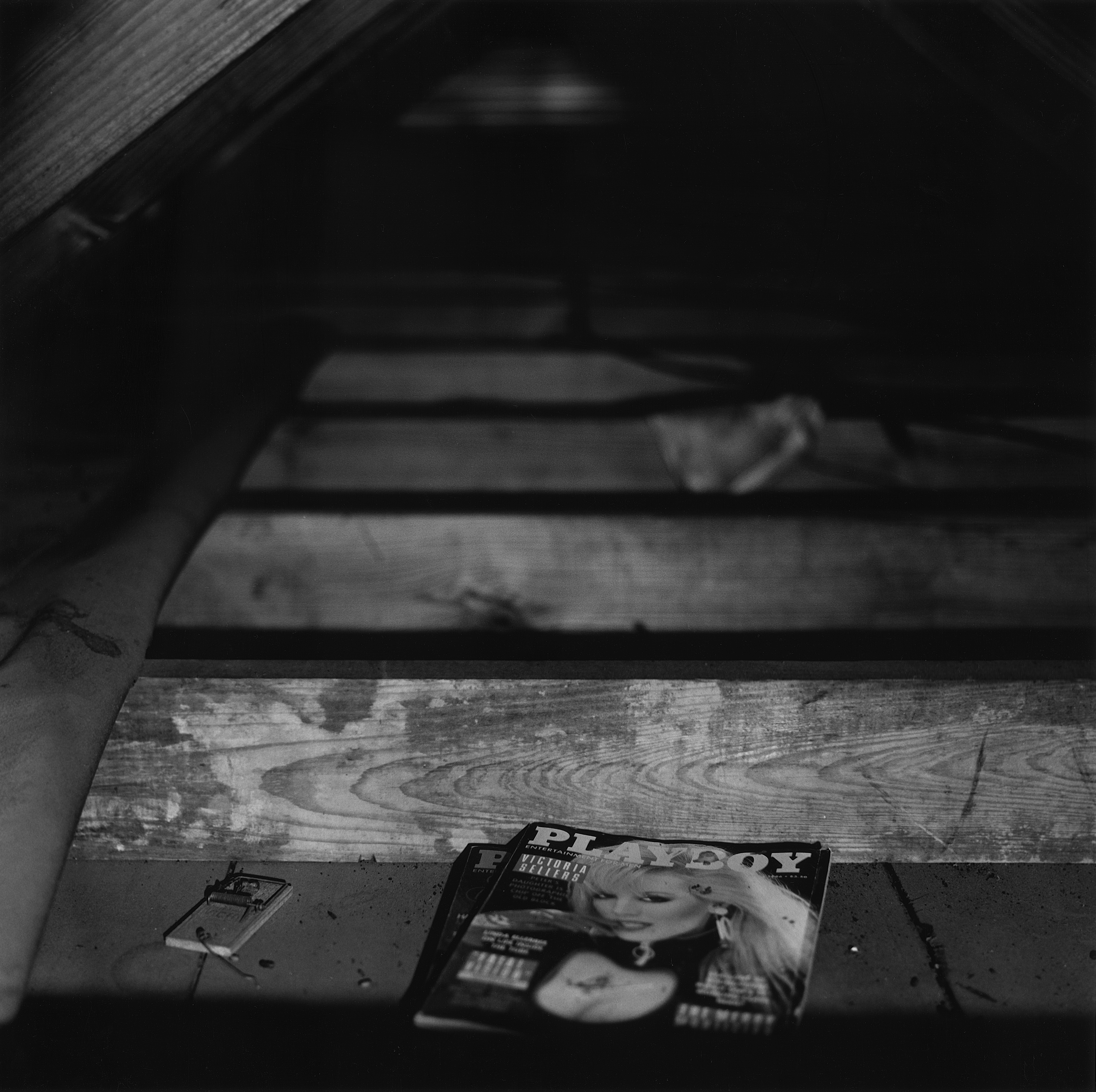

In the late seventies and early eighties pornography wasn’t easy to acquire. A young boy had to put some effort into procuring a magazine or VHS tape. I remember getting excited by pictures of naked breasts in National Geographic.

These days all it takes to see naked women is a click of a mouse. And I do click — a lot.

Sometimes I wonder if other men sitting in front of a computer and ejaculating into a napkin feel good about it. People say there is nothing wrong with masturbation, that it’s natural. If so, then why do I feel so ashamed?

R.D.

Carmichael, California

When I was a boy, my father demanded my mother provide a five-course meal every night. We might have shrimp cocktail, chicken soup, a wedge of iceberg lettuce, rare roast beef, mashed potatoes and gravy, string beans swimming in butter, and apple pie for dessert. Our breakfasts were eggs and bacon, toast with jelly, oatmeal with brown sugar. For lunch my mother packed my sister and me slices of chocolate cake alongside the thick sandwiches in our lunchboxes.

By the time I was twelve, I weighed 190 pounds and jiggled when I walked. The kids at school called me fatty. My mother bought my clothes in the “husky” section of the department store. Then I discovered girls and began dieting. By sixteen I was down to 165, but my life was based largely on denial. It seemed I had to eat less than anyone I knew just to maintain my weight.

After I got married, I couldn’t resist my wife’s cooking, and I went back to eating half a roast or a whole chicken for dinner, sometimes followed by a quart of ice cream. I was so out of shape I could barely climb to the balcony at the symphony and was breathless after two blocks when walking the dog. Then I met a couple of runners who were rail thin, and I thought this might be the way to get rid of my layers of fat. One morning I lumbered around our apartment building — once. The next day I managed to complete the circuit twice. I was on my way.

I bought running clothes and shoes and jogged around the track at a nearby elementary school. I got up at 5 AM and ran before work, when it was so dark the streetlights were still on. Running cleared my head, and the pounds began to come off again. In my first ten-kilometer race I finished last and vowed to do better. I ran my first marathon at the age of fifty, went through a pair of running shoes every six months, suffered shin splints, plantar fasciitis, and black-and-blue toenails. I was thin but still envied emaciated runners who looked like they hadn’t eaten in months. Overcome by guilt if I had a piece of pie after dinner, I stuck mostly to veggies, salads, beans, and rice. But I promised myself that someday, when I was old and no longer needed to stay fit, I could eat whatever I wanted.

I am now eighty-seven. I have an artificial knee. My eyesight and hearing are failing. What I didn’t expect is that my taste buds have failed me, too. Now that I can indulge the food fantasies I suppressed — bingeing at buffets, putting sour cream and butter on potatoes, and eating ice cream with caramel sauce — I no longer get any pleasure from it. A big meal only keeps me up at night and gives me a headache.

Richard Porus

Portland, Oregon

I was unattached, and he was a married man I’d known for years: charming, European, handsome in a craggy way. We agreed on little things, like never putting a glass of water on wood furniture without a coaster. His advances became harder and harder to ignore. I would frequently leave the room.

That he was married carried some weight with me, but, as a former adulterer, I had a forgiving attitude. I didn’t expect him to leave his wife. I knew his family came first. He was a devoted father. I admired that about him.

When I finally gave in to his propositions, we sped in his Porsche to the coast and had a romantic weekend at their beach house. After that, our once-a-week rendezvous mostly occurred at my place. I didn’t think the affair would last more than six months. Then a year went by. And another.

I had stabs of conscience and would imagine breaking it off. I wanted someone who could be mine unequivocally, so I wouldn’t have to sneak around or wait for the appointed hour. I became involved with someone else and stopped seeing the married man.

Then cancer took my breasts and cooled what little physical connection there was in my new relationship. What could he possibly see in a woman with no breasts? Inexplicably, though, my old lover’s ardor was as strong as ever, and we started up again. I felt guilty at first, then lucky that someone still found me attractive.

This past December I lost my hair, but not because of chemo. It just started falling out until I didn’t even have eyebrows or eyelashes. At last, I thought, this would be the end of the affair. But no. He still wants me. I can’t understand why. I’m bald and breastless. Am I convenient? What does he see in me?

In the early days of our affair he used to say, “You are my cocaine.” Perhaps I am just his bad habit. Perhaps he is mine.

Name Withheld