When I was a music major in college, one of my instructors asked students on the first day, “Would you rather lose your hearing or your sight?” I was the only person who chose sight. I cannot imagine being unable to hear music. It has been my irreplaceable companion in life, and I’ve had a lot of jobs related to it: at a college radio station, a record store, and a rock club; on the arts desk of a newspaper; in a smelly tour van and an even smellier rehearsal room. Rock, pop, hip-hop, salsa, ambient, country, gospel, house, techno, soul, blues, jazz, classical — it has all been essential to me.

Kelefa Sanneh was a child when his family immigrated to the United States after living in Ghana and Scotland, and music helped him understand his new home. He studied violin at a young age but became enamored with punk rock as a teenager in Connecticut. When he arrived at Harvard, he also started working at the university’s radio station and, later, at local record stores, devouring different genres and beginning to see how our tastes in music both bring us together and separate us.

After college Sanneh published in The Village Voice and The Source, and he was hired by The New York Times in 2002. In 2004 he wrote an influential essay about “rockism”: the tendency to judge all popular music by the standards of rock and roll, leaving other styles underappreciated. The rockism debate inspired a countermovement, known as “poptimism”: the notion that popular music should be celebrated as such rather than dissected from an elite remove for being too rote, accessible, or simple. He is currently a staff writer at The New Yorker, and his 2021 book Major Labels examines American culture over the last fifty years through the lens of seven genres of popular music. In his view, it’s logical how we’ve decided that different harmonic universes reflect different belief sets.

I have a slight unease with music criticism. One person’s opinion is just that, and sometimes a critic and an artist have a vastly different relationship to the work. Sanneh’s critical voice, however, strikes me as admirably agnostic. His voracious appetite for music — “I’m greedy!” he says — allows him to appreciate a far greater variety of music than the average listener. And in this period of unlimited streaming and endless social division, it might be helpful to look at the parts of our culture that find broad audiences. “Popular music gives you a portal into a whole bunch of different worlds,” he says. “To me, that’s its greatest strength and the single most exciting thing about it.”

We spoke earlier this year, both before and after the birth of my first child, whom I am slowly exposing to the albums that have been a huge part of my life. (As a father of two, Sanneh expressed amusement at my exhaustion, mirroring the reaction of most parents I know who are on the other side of the early months.) Between those conversations, I began exploring music I had once avoided simply because it was popular, and I found comfort — and empathy — in it during some very long nights. Perhaps Sanneh is right: perhaps music is one of our most useful tools for understanding each other.

KELEFA SANNEH

Cohen: Do you think music offers some hope for mending the cultural division in our country?

Sanneh: It offers a way to see the upsides of division. That human process of cleaving into separate tribes is inseparable from the sense of belonging that we seek. To create a community, you have to include some people and exclude others. And if you’re going to create a space that feels intimate, not all 8 billion humans can be in it. You need those two forces: inclusion and exclusion. At different times and in different places you might emphasize one or the other. Say you listen to music that sounds harsh, noisy, and unpleasant to most people. You might belong to this tribe where, in theory, everyone’s welcome, but part of the appeal is that not everyone will want to join. We find this exclusivity in all music communities.

In a politically partisan view, there are only two groups in America today, and they are big. All sorts of people are going to be in my coalition, and we’re going to define ourselves against the people in the other coalition. When you zoom in, you see more fracturing. Depending on how you define it, you might see the country in 2023 as having fewer of those small, exclusive groups than it once did; through social media we’re in conversation with each other more, and sometimes it feels like you’re at a party where you’re hearing every conversation at once. But that lack of separation can cause conflict. Thirty years ago you didn’t know that some random person halfway across the country disagreed with you about something.

Cohen: We’re also seeing musical genres that have embraced each other and are choosing what they want to take from each other — which does seem like a type of unification.

Sanneh: But often, in moments when it seems like things are coming together and boundaries are dissolving, just out of eyesight new boundaries are being erected and new differences are coming into being. I saw a concert about a year ago by Morgan Wallen, a country star who draws from traditional country but, like a lot of modern country music, also uses some electronic drum programming. He grew up listening to hip-hop, and you can hear that in his phrases and the syncopation of his vocal lines, the way he uses rhythm. It wasn’t so long ago that loud electric guitars were considered out of place in country music, and drum sets used to be banned from the stage of the Grand Ole Opry. You can hear Wallen’s music as an example of how some of these boundaries and barriers are coming down. It’s expected that a country star in this day and age will draw from all sorts of genres. But culturally and socially the vibe of this concert was tribal: people were chanting, “U.S.A.!” and, “Let’s go, Brandon!” [A euphemism for “Fuck Joe Biden” — Ed.] And there was a sense among the audience of themselves as a beleaguered minority in the big, cosmopolitan city of New York. That’s an example of how musical inclusivity — sharing between genres — can exist alongside, and maybe even enable, a cultural or social exclusivity.

As you say, we’re living through a moment when musical barriers seem to be coming down. But this is something that’s happened before. Look at the late 1970s, when disco seemed to be swallowing everything. Here was this music that had come out of R&B, but rock acts like the Rolling Stones and Rod Stewart were embracing it. You had the music from Star Wars being rearranged for a disco album. You had the novelty hit “Disco Duck.” Disco was drawing from Latin music. Electronic producers from Europe were becoming part of it. And it just felt like all the divisions were dissolving on the dance floor, which is a utopian idea. But this utopia wasn’t universally appreciated. Some people hated disco. There was a “disco sucks” movement. All that togetherness rubbed certain people the wrong way. For many decades disco was better remembered as the trend that inspired a backlash — and not just from rock fans in the suburbs. In Chicago we saw the formation of house music, a new form of dance music that wasn’t associated with celebrities hanging out at Studio 54. House was deep; it was underground; it was “just for us.” It was as exclusive as disco was inclusive.

Over the last decade or so, thanks in part to streaming services like Spotify, a lot of genres seem to be coming together, but maybe that’s setting the stage for a new backlash, for a new generation of musicians to say, “I don’t want to sound like that. Maybe I don’t even want my music on Spotify. I want to do something different.” As humans we love community, but we also tend to feel oppressed when there’s no escape from a community, when we feel like everything’s the same.

Maybe it’s not a coincidence that we see so much political division happening at the same time as this lack of musical division.

That human process of cleaving into separate tribes is inseparable from the sense of belonging that we seek. To create a community, you have to include some people and exclude others.

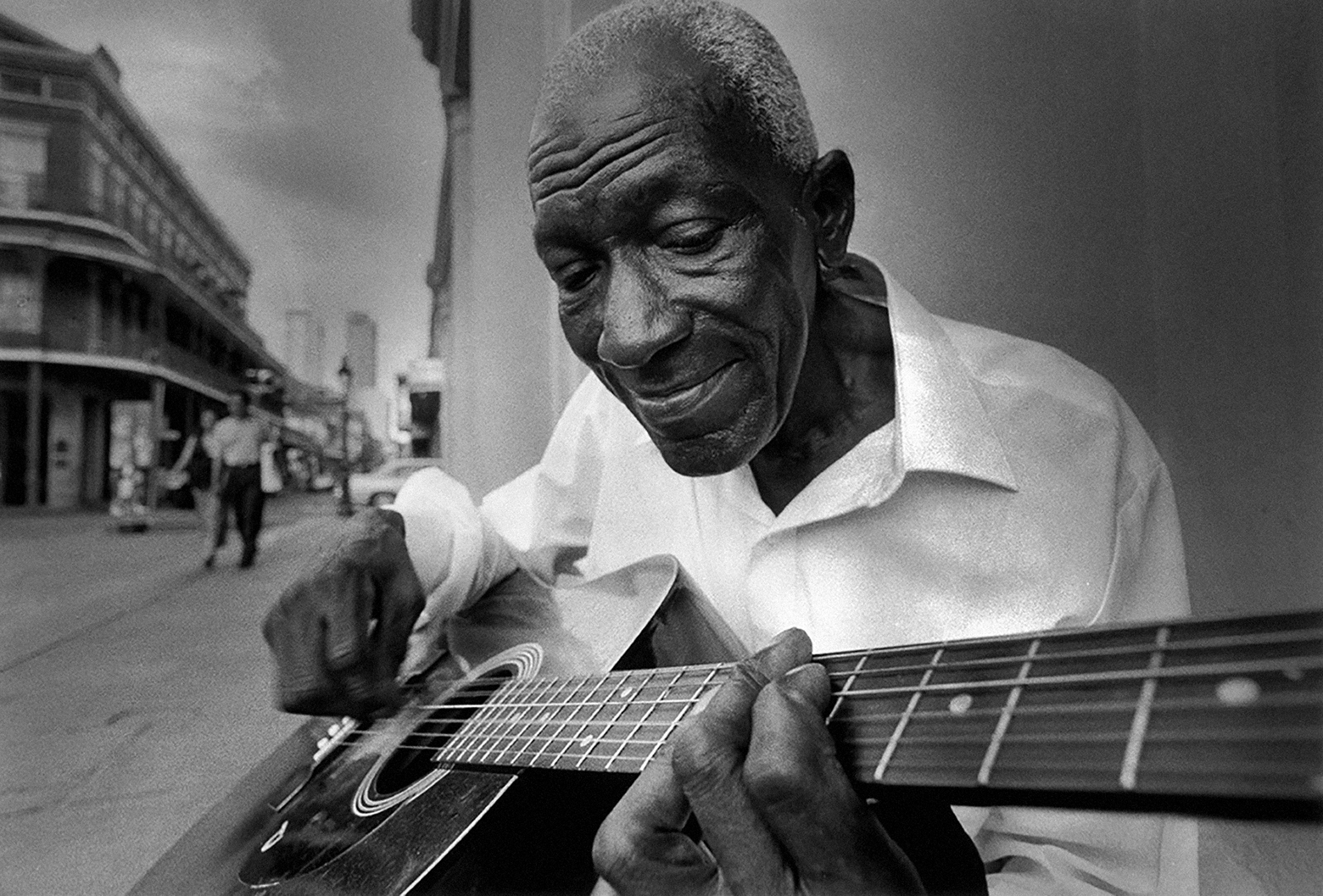

Cohen: Without the blues, we wouldn’t have rock and roll, country, or disco. But since its high point in the middle of the twentieth century, the blues has lost influence — at least, as a popular genre. Why do you think that is?

Sanneh: Just from a commercial perspective of who was making hits over the last fifty years and what you were hearing on the radio, that’s not what blues was doing. It’s become a roots genre. There’s a similar pattern with bluegrass, with jazz, with the Great American Songbook — the Broadway show tunes that were once at the center of popular culture and now are nurtured in conservatories. Once in a while they break through, and people remember the incredible heritage of this music. That seems normal to me. Part of what I like about popular music is the sense that everyone’s scrambling to create something new. That’s what sets popular music apart from other musical traditions, including classical and composed music, where the skill level is incredibly high, but the music is not in intimate conversation with people’s everyday lives and isn’t as influenced by current fashion and culture.

You don’t have to be a connoisseur to hear popular music. You experience it whether you like it or not. It’s the music you hear while shopping. It’s the T-shirt you see someone wearing. Are people dancing to this at clubs? Are they listening to it in their car? It’s meant to fit into your life, which is different from music that’s designed to make you stop what you’re doing and sit in your seat and watch the orchestra play. Popular music tends to seep into your consciousness when you’re only half paying attention.

Cohen: Jazz has had a similar trajectory to blues. It’s certainly less popular now than it was forty or fifty years ago. There are scenes like Los Angeles and London and Johannesburg that have made ripples in recent years. But jazz is also much more harmonically complicated than blues. I love blues, but you could argue that one of the reasons it has fallen out of favor is that it just doesn’t have as many ideas. A twelve-bar blues has a certain pattern, but it depends on the skill of the person performing, the story that they’re telling, the aesthetic that they’re bringing to it, whereas jazz has far fewer limits.

Sanneh: I hear a lot of blues in hip-hop, especially in the last twenty years, when the influence of the South has been increasingly prominent. The most important stars in that world started paying more attention to tone and timbre and less attention to lyrics and vocabulary. It became a more melancholy, moaning style that to me sounds very similar to the blues. It’s maybe not a coincidence that these are both what we think of as Black Southern art forms.

The question of musical complexity is an interesting one. In jazz you have musicians talking about, say, Mixolydian modes, and it’s very self-evidently complex. But listen to a hip-hop track by Kodak Black and try to diagram exactly where the syllables are landing on the beat and what he does with his delivery to keep you interested; there is a lot of complexity there, but it’s not often discussed as complex. Part of the appeal is the sense that this person is just talking to you, that it’s something he can roll out of bed and get on the microphone and do. That’s an illusion, right? These artists are virtuosos. But it’s an exciting illusion because it creates a sense of intimacy. That’s something hip-hop has in common with the blues: the listener is getting a real story in a way that can feel artless but is incredibly artful.

Cohen: With jazz, do you think that the complexity is a greater hurdle for people? Is that why it doesn’t have the same role in popular music that it once did?

Sanneh: When jazz had a more central place in popular music, I don’t think your average person who was enjoying the records was necessarily thinking about modes and harmonic shifts. But sometimes when a form of music gets less popular, a greater percentage of the fans are experts almost by default. Many people who listen to jazz now are knowledgeable about the music in a technical way. If we lived in a world where hip-hop wasn’t as popular, and to be a hip-hop fan meant that you were a bit of a connoisseur or expert, then maybe the complexity within hip-hop would be foregrounded. You see a little bit of that now with Kendrick Lamar winning the Pulitzer Prize in 2018 [for his album DAMN. — Ed.] and people studying the way he uses imagery and symbolism in his rhymes.

We could analyze hip-hop in a more technical way. We could talk about the way rappers sit in relation to the beat, and how that’s switching throughout the song. I remember when the Game — a rapper from California — came along, I was shocked by how far behind the beat he was. It felt like the musical equivalent of someone putting their driver’s seat way back to signal cool and nonchalance. When I first heard Chief Keef, from Chicago, he was so far in front of the beat that it felt like he was rushing. Whether that kind of technical analysis affects the way we listen to hip-hop is a question about the culture of the listener. When hip-hop, or any genre, is popular and resonating in the culture, you tend to have nonmusical conversations about it. All these narratives around the music — youth culture in Chicago, crime and violence, business success — come to the fore because they seem more exciting. It’s more fun to talk about the cultural impact than it is to talk about how in the 1980s Rakim changed the way rappers use enjambment to lengthen the average line length of a verse.

We see the same thing in heavy metal. A scholar did a technical study of the Swedish death-metal band Meshuggah, looking at how they use rhythm. But part of what’s fun about metal is the cultural meaning of it. The technical side is interesting. I have some knowledge about that — I played violin when I was a kid. But there’s a reason classical music didn’t take hold of my heart the way popular music did. With popular music there’s a sense that you’re eavesdropping on someone’s culture. The driving question in my life has been “What are those people doing over there?” For me it’s also been a question about America. I’m an immigrant. I moved here when I was five. My parents are both from Africa. So I have a curiosity about America: How does Nashville work? What are they rapping about in Texas? What’s the LA rock scene like? What was really happening in the eighties? Popular music gives you a portal into these different worlds.

You don’t have to be a connoisseur to hear popular music. You experience it whether you like it or not. It’s the music you hear while shopping. It’s the T-shirt you see someone wearing.

Cohen: You’ve described hip-hop as perhaps the greatest cultural export of the U.S. Its influence is felt in every country: through music, language, fashion, and curatorial style. But it came from such a specific place and time, and it prides itself on authenticity. How do other cultures navigate that?

Sanneh: The hip-hop-inspired music that I love the most uses the attitude and style of hip-hop to create something new: funk carioca in Brazil; reggaeton in Puerto Rico (which is obviously part of the U.S. but in some ways is a separate culture); kwaito and, more recently, amapiano in South Africa; the various Afrobeat sounds coming out of West Africa; even dancehall reggae, which evolved in parallel with hip-hop. All those styles are following a similar blueprint, but the rhythmic pattern, the use of vocals, and the vibe are different. They don’t sound the same, just as hip-hop in the U.S. doesn’t sound the way it used to. NBA YoungBoy does not sound like Run-DMC.

In country music, if an artist has a strong cultural identity, like Morgan Wallen does, it gives them more freedom to experiment with different sounds and styles. And the opposite is also true: if you’re using very traditional country instrumentation — mandolin, fiddle — you can be a hipster in Brooklyn, and your cultural cred can come through the traditionalism of the music.

Hip-hop has this cultural identity that gives people more room to explore. Part of the reason hip-hop is so influential is that different people can tap into its sensibility, even if the music they’re making is not part of the same family tree. We can describe a pop singer, or even an athlete, as being kind of hip-hop.

Cohen: My question was more about the ways people appreciate — or create — music that comes from a different set of experiences than their own.

Sanneh: That question is unanswerable. We’re humans. We’re primates. We hear sounds, and we imitate them. There’s been this tension in hip-hop from the start, because there was something so seductive about it that people outside the culture were drawn to it. “Rapture” by Blondie is one of the first hip-hop hits. Mel Brooks and Rodney Dangerfield made parody hip-hop records in the early eighties. Before the genre had even established itself as a commercial force, there was something about the music that made people want to borrow from it — or steal from it, some would say.

At the same time, hip-hop is obsessed with authenticity, which is a hard thing to define. Often the people who succeed in hip-hop are able to stake a claim of authenticity, even if their lives are very different from the lives of the people they’re talking about. The people who’ve been inspired to borrow or steal from it are often really concerned about authenticity. Take someone like Kid Rock, a white guy who grew up in suburban Michigan. When he was starting out, he had to figure out how to prove that he was really a part of the hip-hop scene. That led to a long and interesting career, in which he’s now thought of as more of a country singer — and there’s a different authenticity debate over his identity as a country singer. The question can never really be settled.

There was a moment in the eighties when people thought hip-hop had turned into a novelty and was going to be over soon, but it’s been going strong for decades. Some people mark 1973 as the year hip-hop was born. So hip-hop has existed for fifty years and still has a huge impact on popular culture, still is vibrant and commercially important, still has this connection to working-class Black neighborhoods all across the country, still speaks to and for those people. That’s incredible. That’s something I wouldn’t have predicted: that in 2023 hip-hop would remain both super popular and somehow countercultural.

Cohen: There’s a pattern where musical genres from the U.S. go overseas and get turned into something else. Blues and R&B and early rock and roll crossed the Atlantic and came back as the British Invasion. Electronic music from Chicago or Detroit went to Europe and became something completely different. What do you make of this pipeline?

Sanneh: That transatlantic conversation is defined by asymmetry. In the UK it’s harder to ignore what’s happening in America, whereas in America we are only inconsistently interested in what’s happening over there. They have regularly created huge stars who resonate here, from the Beatles to Coldplay to Adele. But there are also big British bands that never become popular in the U.S. Ask the average American listener who the Chameleons are, and they probably have no idea.

There have certainly been times when listeners in the UK and Europe have appreciated things happening musically here that Americans didn’t appreciate. I think it can be hard to appreciate cultural phenomena when you’re too close to them, especially when it’s just these working-class kids in a nightclub or on YouTube. We have cultural preconceptions about who’s valuable, who’s smart, who’s interesting, and artists who don’t meet those criteria can get ignored. But with the passage of time we’ll say, “That was actually amazing.” A major example of this is house and techno in the 1980s, which made no mark on the American pop charts but sparked musical revolutions in the UK and all over Europe — so much so that many American listeners in the 1990s and 2000s thought of house and techno as European music, even though those genres were invented in Chicago and Detroit, respectively. Of course, the conversation isn’t totally one-sided. House and techno were influenced by some of the music coming out of Europe in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Sometimes we’re blind to what’s going on closer to home, and it’s helpful to have an outsider from across the ocean say, “You should be paying more attention to this.” I started writing about music because there was all this hip-hop in the U.S., especially from the South, that I felt wasn’t being celebrated the way it should have been. Even people who loved and wrote about hip-hop didn’t seem to appreciate what was happening in New Orleans, Houston, and Miami. I’m not from any of those places, but I thought it was important to celebrate this music while it was being made. Still, we’re always going to be elevating one genre or artist while ignoring another. Even for someone like me, who listens to a ton of music, there’s more happening than I could ever possibly keep track of. It’s frustrating, but it’s also exciting.

Cohen: We often see cycles of nostalgia, where styles from the past come back into favor. I’ve wondered if that means we’ve hit some sort of creative ceiling.

Sanneh: I’m skeptical of nostalgia, especially when music is self-consciously retro, and musicians are wearing old-timey hats and using old-timey slang and trying to re-create some earlier era. I’ve had moments when I’ve been worried about the increasing prominence of retro culture. It’s possible to look at movies, fashion, and music and wonder if everything is a recycled version of something else. The next step is to wonder whether my own skepticism of nostalgia is itself a form of nostalgia for an earlier time when art was supposedly more original. Nostalgia is a narrative of cultural decline: “We used to be really creative, and now we’re not, so let’s go back to a time when country music was country, when hip-hop was real, when rock and roll was raw.”

The power of human culture to create something new is strong. You could have looked at poetry in the middle of the twentieth century, after modernism and formal experimentation, and said, “We’ve reached an end with poetry.” Then in the 1970s you get the rise of hip-hop. What hip-hop was doing with words didn’t seem formally inventive, but the culture it represented made hip-hop revolutionary. The music was linked to a new way of seeing the world, a new attitude. It created something new without rewriting the rules of poetry or finding ways to put two words together that no one had ever thought of.

Sometimes novelty in music will mean a new rhythm, a new kind of instrument, or a new sound. The rise of Auto-Tune, which kind of blurs the boundary between rapping and singing, unlocked possibilities that people are still exploring twenty-five years later. So there is that kind of formal and technological innovation. But often when we talk about something new in the culture, we’re talking about a vibe, an attitude, and I don’t think it’s possible for us to run out of attitudes. Look at the extraordinary explosion of Hispanic music of various kinds, from Bad Bunny in Puerto Rico to Natanael Cano, and the interesting ways in which all of this Spanish-language music is cross-pollinating. Even though Bad Bunny is drawing from various musical traditions that came before him, the way every musician does, there is something unprecedented about him. If you consider Bad Bunny hip-hop, then he’s maybe the most important hip-hop act in the world right now. But he’s not a rapper in a traditional sense. That’s precisely what makes him so good and so influential. I think people will always find ways to do things that feel different, even if they can’t be described in technical terms, like, “The rhythm used to be in 4/4, and now it’s in 6/8.” It has more to do with the artists’ culture: Who are these people? How do they think of themselves? How do they present themselves?

It can be hard to recognize in the moment if we’re living through a golden age of this or that genre. Often, by the time society at large is ready to celebrate something, it’s been around for a while.

Cohen: What do you make of the explosion in popularity of Spanish-language artists?

Sanneh: It might partly be a function of how we measure popularity. In the early 1990s the record industry stopped having record stores anecdotally report which albums were selling well and started using the SoundScan system, where the barcode of every CD sold got scanned to produce an actual count. When that happened, hip-hop and country music turned out to be way more popular than people thought they were. The musical establishment was overrating the popularity of rock and pop. It’s not that hip-hop and country suddenly got more popular; it’s that we could suddenly see how popular they already were. That changed the industry. Labels invested more money in those genres, and the media started to reflect their popularity.

I think something similar might be happening today, with streaming platforms tracking what people are listening to all over the world. The market is a lot more international. We used to have very little idea in the U.S. what people were listening to in Argentina. Now we know. And with that new popularity, there’s this ongoing fusion and outpouring of creativity that starts to get super popular in the 2000s with the rise of reggaeton. It’s mixing and matching from different Latin countries, so you’re getting not just the rise of Bad Bunny and Rauw Alejandro in Puerto Rico and Rosalía in Spain, but also Mexican artists like Oscar Maydon. Just like with the birth of hip-hop, these new musical traditions are not only finding new audiences, they are creating them. Spanish-language artists are hugely popular in Europe, and you hear their influence in some of the music coming out of Africa. It wouldn’t surprise me if people looked back in twenty or thirty years and said, “This was the Bad Bunny era” — that those Spanish-language musicians have the same kind of influence today as the hip-hop pioneers and the punk pioneers did in the 1970s. That’s been the history of music: genres get older and lose popularity, and new genres arrive. It can be hard to recognize in the moment if we’re living through a golden age of this or that genre. Often, by the time society at large is ready to celebrate something, it’s been around for a while.

Cohen: I’m sure you know the quote about how writing about music is like dancing about architecture. Do you think this applies to analyzing how people listen — or how people should listen — to music that amplifies this type of cross-pollination? It’s one thing for a Puerto Rican artist like Bad Bunny to incorporate different elements of the Spanish-speaking diasporas. Should the cultural origins of musicians who draw from other genres be taken into context? Like if a white Irish guy incorporates the rhythmic cadences and vocal stylings of reggaeton and becomes hugely popular in Europe?

Sanneh: I tend to be more descriptive than prescriptive on the question of what people listen to. In general, listeners want the perception of authenticity. So people who are excited about Latin trap music, or whatever name gets affixed to it, enjoy the sense that they’re hearing directly from that culture. Hip-hop fans over the years have sought out the “real thing.” At times they have reacted negatively to artists who’ve been perceived as interlopers, and artists, in turn, have been careful to remind fans, “Yes, I’m really part of this world.” But other fans like to see someone from their world making that kind of music. Maybe it’s a pop songwriter borrowing rhythms from somewhere else. It’s still complicated today because part of popular-music tradition is new people coming in and popularizing a genre for a new audience. Eminem is a white rapper who also happens to be one of the most popular rappers of all time. Probably not a coincidence, right? But, in his case, he was very self-conscious about his whiteness and worked hard to emphasize not just his relationships with Black rappers, but his indebtedness to people like Dr. Dre. So he could claim to have this authentic connection.

What I expect to see with the Bad Bunny wave is English-language pop stars borrowing from his style — or stealing from it, if you prefer. This is all part of the musical tradition. Previously the common wisdom was that, for a Spanish-language singer to cross over, they had to sing in English. We saw the opposite of that when Justin Bieber jumped on a remix of “Despacito,” in Spanish, to cross over the other way. You even see it with Rosalía, who is from Spain but on her most recent album is drawing on music styles from Puerto Rico and other places. That’s a kind of crossover within the Spanish-speaking world. I would expect these trends to continue to be complicated and unpredictable.

I’ve never been interested in saying, “Oh, this person has to be respected,” or, “You shouldn’t rip off this kind of music,” because part of the fun of hip-hop, for example, is how it’s built on an ethos of ripping other artists off. “Rhymin’ and stealin’,” as the Beastie Boys put it. It’s Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force borrowing “Trans-Europe Express” by Kraftwerk. It’s the idea of taking someone else’s beat and rhyming over it or incorporating a snippet of another song into your music. The human urge to imitate is fundamental.

Cohen: Well, there’s a certain complication that comes with an artist like Morgan Wallen, whom you mentioned earlier. [In January 2021, Wallen was caught on camera by a neighbor using a racial slur while drunk. He was dropped from mainstream country radio almost immediately, but his streaming numbers rose to record-breaking heights. — Ed.] He’s using the rhythmic patterns and traditions of hip-hop, but he’s got a song called “Rednecks, Red Letters, Red Dirt” — the lyrical messaging is slyly vague but also seems pretty clear. Country music like his is entangled with hip-hop in a complicated way, where the messaging behind some of it seems at odds with where hip-hop comes from and who makes it.

Sanneh: I think often we simplify conversations about divisions within America in ways that can flatten or obscure what’s actually happening. There’s this sense of Team Red and Team Blue, and hip-hop is Team Blue because it’s Black music. But if you look at the actual history of hip-hop and what rappers have said and written in lyrics, it’s complicated. The ethos of hip-hop doesn’t fit neatly into a Left/Right, red/blue divide. One of Morgan Wallen’s first projects after he got caught using the N-word by a neighbor is a song he made with Lil Durk, a rapper from Chicago who has as much hip-hop credibility as anyone and has been putting out amazing records for more than a decade. Lil Durk was like, “Whatever, Morgan Wallen’s a cool guy.”

So I would question the assumption that hip-hop fans or rappers or people in that world would necessarily all have one point of view on Morgan Wallen. But it’s true that he has this very strong, complicated cultural identity. He’s from a small town in Tennessee. He didn’t grow up listening to country music, but that’s the culture that surrounded him. And this is something that people in country music are trying to figure out: What is this culture? If country music is defined more by its culture than by the instrumentation and style of the music, then what is that culture? Many years ago you could have said it was Southern or rural music, but I don’t even know if that was true by the seventies. It certainly wasn’t true by the nineties, when country music was not particularly Southern or rural. So was it defined by its whiteness, and, if so, what does it mean to have a music genre that is unapologetically, disproportionately white? There’s a movement now to make a more integrated vision of country music, and certainly there are Black artists in country music: Kane Brown is a big star, and he has African American heritage. So what is this culture? And what do we expect from it going forward? In a broader view, will more musical genres become integrated, and will race become less salient in music? It’s easy to imagine that being a good thing in country music, but I’m not sure we would think it’s a good thing in R&B or hip-hop.

Knowing who wrote a song, and knowing things about that person, is an important part of our enjoyment of music. The job of being a pop star includes managing what people know about you precisely so they can form these parasocial relationships. And musicians have more opportunities than ever to express themselves, so we know more about them than we used to. Maybe some listeners have come to expect a little too much transparency from artists.

I want popular music to reflect the world and the cultures in which it was created as vividly as possible. So if many Americans are living in segregated communities or think of their identity in racial terms, I want the music to reflect that. I want to hear what people who vote for different candidates are listening to. I want to see if I can enjoy it. I want to hear in pop music everything that’s happening in the U.S., from patterns of residential segregation to violent urban neighborhoods to increasing Hispanic populations.

Cohen: Because what’s popular reflects what communities do or don’t value?

Sanneh: Because the thing popular music does so well is that it tends to reflect the preferences of both poor people and rich people. That’s something novels and fine art and classical music don’t do as well. Part of what I love about popular music is that feeling of eavesdropping on the community of people who love it, which is where a lot of its energy comes from. It’s partly a tribal energy: I’ve definitely felt it at hip-hop shows and at punk shows. When I’m at a Morgan Wallen concert and people are chanting, “Let’s go, Brandon!” between songs, I recognize that energy. That’s one of the forms of excitement that music can provide: the sense that it is reflecting something or resonating with someone else.

Cohen: After watching Leaving Neverland [the 2019 HBO documentary about two men who say that Michael Jackson groomed and sexually abused them when they were children — Ed.], I listened to Thriller again; I still really enjoyed that record, but it felt like a moral choice whether to enjoy it or not. I have not returned to the work of R. Kelly [the R&B artist sentenced to thirty-one years in prison for production of child pornography, sex trafficking, and other offenses — Ed.], because that moral choice feels thornier. Both men are exceptionally talented and have produced some extremely popular music. How do you feel about enjoying music created by someone you know has done immoral things? Does it matter?

Sanneh: Streaming and social media have made music listening more public. Before, if you had a record by some disreputable person, no one knew whether you were listening to it, and the artist no longer benefited financially from your listening. Nowadays, when you’re streaming a song on Spotify, you can share that on social media, and your listening means some small fraction of a cent goes to the musician or the songwriter. This has led to the idea that there’s something consequential when you listen to a song. It encourages people to consider which artists they feel OK about listening to: you may be seen as supporting someone you might not want to support.

Part of the enjoyment we get out of music is this sense that we like this person, we know this person: “I’ve been listening to Lionel Richie for forty years; I love this guy.” But when we discover something disturbing about them, like with Jackson or Kelly, it can change that relationship. On the other hand, we also listen to musicians who seem very different from us. A lot of people, during their early encounters with hip-hop, weren’t sure how seriously to take the lyrics, because the person on the record sounded like a scary dude. That was part of its appeal, too. It’s interesting to listen to music by someone who’s very different from me, even someone who might believe or have done deplorable things.

I don’t even know if it makes sense to talk about separating the art from the artist. Part of the reason we care about music in the first place is because we care about the people who make it.

Cohen: Some of these questions about separating the art from the artist, especially around examples like Wallen and R. Kelly, are asking us if we all occupy the same moral universe. If, all of a sudden in the United States, a neo-Nazi songwriter became extremely popular, and you and I found ourselves enjoying the music, I’d feel uncomfortable. Should we hold pop stars to the same standards of that universe?

Sanneh: I don’t even know if it makes sense to talk about separating the art from the artist. Part of the reason we care about music in the first place is because we care about the people who make it. If we’re talking about music made by someone known to have committed horrific crimes, then part of your thought process is trying to figure out if you’re comfortable listening to it. It’s possible to say, “I enjoy this person’s songs, but they should be in jail,” or, “I enjoy this person’s songs, but they shouldn’t be on the radio or Saturday Night Live.” As a music writer, what I might do in that situation is explain the appeal of that singer, explain what it is that some people love about their music.

Whatever the norms and values are in any society or among any group of listeners, musicians will violate them. It’s a big part of the history of hip-hop, which has continually violated norms in ways that have led to criticism. There have always been people saying, “There’s something horribly wrong with this music. We’ve got to fix it. It’s silly. It’s evil.” Sometimes, after the fact, people look at what was at the center of the controversy and find a way to celebrate it. Or there’s a sheepish course correction: Guns N’ Roses left their song “One in a Million” off their box set, and I don’t believe they currently perform it. [The 1988 song was infamous for lyrics attacking “immigrants and faggots” and using racist slurs. — Ed.] That was a huge controversy at the time. You had the biggest rock star in the country singing, “Police and [N-words] . . . get out of my way.”

Listeners have to ask themselves, “What is my tolerance for cognitive dissonance?” Mine is super high. I can listen to a neo-Nazi metal band and enjoy the music but also think about the evil ideology being expressed. It’s fascinating to think about the different representations of evil in rock and roll, going back to the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil”; to think about what good and bad mean in that genre.

Cohen: But it can be hard to listen to something morally objectionable and not feel like you’re complicit.

Sanneh: You’re probably always listening to somebody whose views you don’t entirely share, or you’re supporting a cultural ecosystem and an economy that you don’t feel 100 percent good about. Music can distract you from that complicity or heighten those contradictions. Again, I really do reject the idea that it is somehow desirable or possible to separate art from artists. Context is part of popular music. If you were reading an analysis about a classical symphony, you would expect a more musicological approach, whereas an analysis of a pop song is often a work of amateur sociology. The thing that makes the song rich is not the chord progression; it’s the way it fits into a broader cultural conversation. It would be delusional to imagine that you could somehow separate a pop song from that. It’s easy in the abstract to say, “I’m into all sorts of music,” but eventually you have to confront the tribalism expressed at the concert where people are chanting, “Let’s go, Brandon!” You have to confront your own tribalism. Figuring out how your culture and beliefs and the culture of the music and the artist rub up against each other is one of the things we can enjoy about music.

Music is a relatively harmless way to think about political divisions or to engage with different cultures without having to join them. It could be voyeuristic, or it could be driven by sympathy. Hip-hop, especially in the last thirty years, has often appealed to people who live in communities that are much less violent than the communities depicted in the lyrics. When people talk about the division in America, they’re usually decrying it. Through music you can look at those divisions and see an upside, because they also create a sense of community. Whether it’s a small club or a big arena, even if it’s fleeting or illusory, that sense of doing something together — that’s a powerful feeling.