I WAS INTRODUCED to James Howard Kunstler’s work in the summer of 2008 when my husband started reading his book The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-first Century (Atlantic Monthly Press). The country was freshly reeling from the collapse of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the mounting foreclosure crisis — all of which Kunstler had predicted in The Long Emergency, published in 2005. It was bizarre to hear my husband read aloud sections of the book that sounded like daily news broadcasts. While presidential candidate John McCain was reassuring voters that “the fundamentals of our economy are strong,” Kunstler had correctly predicted their collapse. How had he connected the dots far more accurately than our political and economic leaders had? What did he know that they didn’t — or, at least, weren’t telling us?

I’d been reluctant to read The Long Emergency — whose title refers to the long-term crisis Kunstler predicts will be brought on primarily by declining oil supplies — because I’d feared it would be debilitating, but I didn’t find it so. Kunstler is a superb and colorful writer, but, more importantly, The Long Emergency is helpful — fortifying, even — in the way a weather report is helpful. Kunstler isn’t an advocate of his forecast; he’s just telling us to wear a raincoat. And maybe buy a boat.

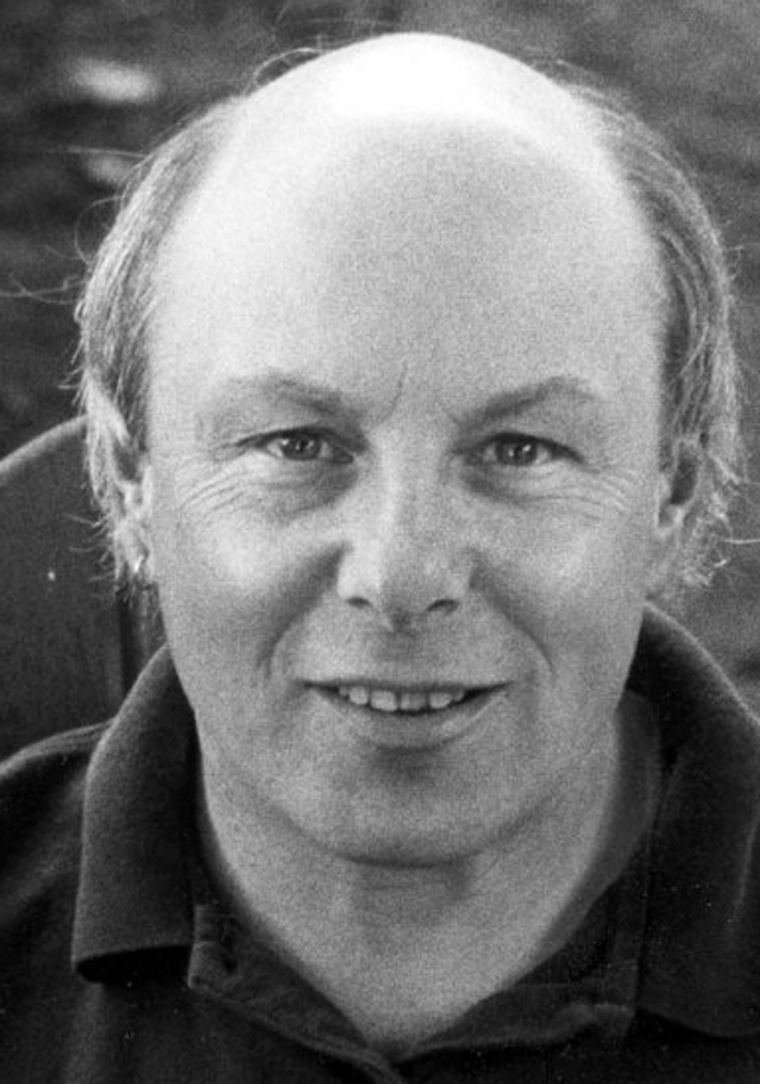

Kunstler is the author of ten novels, including his most recent, World Made by Hand (Atlantic Monthly Press), but he is probably best known for his scathing indictment of suburban-sprawl development and other land-use mistakes in his books The Geography of Nowhere, Home from Nowhere, and The City in Mind (all Simon & Schuster). Born in New York City in 1948, Kunstler lived briefly in the suburbs of Long Island in the fifties before his family returned to the city. He graduated from the State University of New York at Brockport, worked as a reporter and feature writer for a number of newspapers, and became a staff writer for Rolling Stone magazine. In 1975 he quit to write books full time. Although he has been active in the New Urbanism movement, he admits he has no formal training in architecture or city planning.

Kunstler also writes a weekly blog, provocatively titled Clusterfuck Nation (www.kunstler.com), in which he comments on current events and continues to offer dire warnings about the future. While our leaders in government and finance debate which strategy will bring us to “full recovery,” Kunstler maintains that our efforts to return to our former way of life are nothing but an expensive and futile attempt to “sustain the unsustainable.”

Kunstler has lectured at Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Dartmouth, Cornell, MIT, and many other universities, and has appeared before such professional organizations as the American Institute of Architects, the American Planning Association, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He lives and maintains a large garden in Saratoga Springs, New York, an area he believes will fare better than most during the Long Emergency. He spoke with me twice in April of this year.

JAMES HOWARD KUNSTLER

Goodman: On the very first page of The Long Emergency you speculate that the U.S. as a nation might not survive the converging crises we face. What brought you to this conclusion?

Kunstler: I came to write The Long Emergency after having written several books about the fiasco of suburban America as a development model. It was becoming increasingly obvious to me that we had made some tragic collective decisions about how we live, and that soon a permanent shortage in oil and natural gas would make those living arrangements untenable.

In the midnineties a number of retired senior geologists from the oil-and-gas industry began writing publicly about their concerns, which happened to confirm my suspicions. I’m thinking primarily of Colin J. Campbell, retired geologist for Texaco, British Petroleum, Amoco, and Fina; and Kenneth Deffeyes, professor emeritus of geology at Princeton University, whose book came out at about the same time as mine. These men said that we were heading into a permanent problem with oil, which became known as “peak oil.” The idea was that we’d reach a peak in oil production early in the twenty-first century, after which production would decline permanently, producing unforeseen consequences.

I believe we have reached that peak within the last few years, and the collapse of the financial system is more a result of peak oil than of overzealous mortgage lending, which is only part of the picture. Without cheap oil, we can no longer depend on our regular 3 to 7 percent annual economic growth. And without the expectation of growth, the paper wealth of the market loses its perceived value, because we can no longer service our debt. It’s really the end of a revolving-debt economy as we have known it.

Our predicament isn’t just about the oil we use to run our cars and heat our homes; it’s about the complex systems we’ve developed based on the availability of cheap oil. It’s no exaggeration to say that every benefit of modern life — from airplanes and air conditioning to supermarkets and hip-replacement surgery — owes its existence in one way or another to cheap fossil fuel. In particular, the American way of life, which is virtually synonymous with suburbia, can run only on reliable supplies of cheap oil and gas. Even moderate deviations in price or supply will make the logistics of daily life difficult.

Agriculture is an example of a complex system we depend on — and obviously a crucial one. We pour enormous amounts of oil- and natural-gas-based products on the soil in order to get all those Cheez Doodles out of it. This system is going to come under stress because of the rising price and decreasing supply of oil. Last summer, as we got into the planting and growing seasons, the price of oil began to rise astronomically. It went from $60 a barrel to $147 a barrel in July, which hammered the farmers.

Of course the price of oil has crashed since then because of the falloff in demand brought about by the financial crisis. But I think the next act in the drama is going to be a renewed set of problems with oil prices and supply. These could begin at any time because of the instability in the global oil markets themselves, which are at the mercy of geopolitical trends and relationships among nations. They’ve entered a zone of extreme volatility.

We’ve also discovered new subplots in the oil story, such as the oil-export problem. Jeffrey J. Brown, an independent petroleum geologist in Dallas, has predicted that major oil-exporting nations will begin to hold on to their supplies for their own use. Mexico is the poster child for this situation. As Mexico produces less each month and uses more of its oil domestically, its exports are going down. It happens that Mexico is the third-largest source of imported oil for the United States. So we’re going to lose our third-largest source of imports relatively soon, and there’s not even any discussion of this in the media.

Oil nationalism is another subplot. Only about 7 percent of oil is currently produced by major oil companies like Chevron, Shell, BP, and ExxonMobil. The rest is produced by nationalized oil companies such as Pemex in Mexico, Aramco in Saudi Arabia, Petrobras in Brazil, Petroleos de Venezuela, and so on. For practical purposes the Russian oil companies are also under the direction of their government. A number of nationalized oil companies, rather than putting their oil on the auction block of the futures market, are entering into “favored-customer” contracts with certain nations, thus removing their product from the global bidding process. Since many nations don’t like the U.S. very much, we’re not likely to be their favored customer. The end result is that we’re liable to face a severe shortfall in oil imports, which we’re not prepared for. If the government is paying attention to this, it’s at a behind-the-scenes level.

Another complex system we depend on is transportation. In the U.S. that system is based on cars and planes. Both are petroleum-intensive. If we have volatile prices in liquid fuels, we will have enormous problems with our transportation system, which we’re already seeing. This in turn affects our model of development, which is suburban sprawl. And now that system has begun to collapse.

Goodman: Are you saying that rising oil costs brought on the mortgage crisis?

Kunstler: The peak-oil problem means that we can no longer expect to run an economy based on never-ending growth, which means ultimately that we can’t service our debts at any level — personal, corporate, governmental. We’re comprehensively broke. The securitization of mortgages was one of the so-called products that allowed the financial industry to swell from around 8 percent of our economy thirty years ago to over 20 percent just before the crash of 2008.

The commercial-real-estate sector, which accessorizes the suburban-development pattern by providing strip malls and big-box stores near suburban neighborhoods, is now imploding, as well. Unfortunately in the last several decades we’ve gotten rid of our manufacturing economy and replaced it, not with a postindustrial economy or an information economy or any of these other bullshit economies we think we created, but with a suburban-sprawl-building economy. We built more suburban tract houses, more strip malls, more highways, and more chain stores. That system has now entered a state of terminal decline.

Huge numbers have lost their jobs in the construction industry. Plenty of people who used to drive to work in their Ford F-150 pickups are unemployed. The companies that supported them are going out of business or taking each other over. Pulte recently took over Centex; they are two of the largest production home builders in the country. Recognizing that there isn’t going to be enough work for both of them, they merged.

The media promote the idea that we are waiting for the market to hit bottom, and then everyone will resume their normal habits and practices, but it isn’t going to happen. We’re done building suburbia. It’s obsolete. The production home builders are going away, and they’re not coming back. A lot of the cheerleaders and enablers for them — the realtors, lenders, and appraisers — are going to go out of business too.

Much of the so-called wealth we generated was based on housing prices going up, so people could use their homes like ATMs, borrowing against their value to buy more stuff. We had a so-called consumer economy based on easy credit — essentially financed by the rest of the world.

Goodman: In your book you explain that the U.S. economy — and, as a result, the world economy — has been built on a series of bubbles: the cheap-oil bubble, the housing bubble, the easy-credit bubble.

Kunstler: Yes, and all of these bubbles were nourished by the final blowout of the cheap-energy fiesta that began around 1985, when the effects of the various oil embargoes and crises of the 1970s finally wore off, and the last great oil discoveries went into full production: the North Slope of Alaska, the North Sea between the UK and Norway, and the Siberian oil fields in Russia. As a result the world was flooded with oil, and the price of oil hit bottom around the turn of the century at ten dollars a barrel. That was cheap oil. The price stayed relatively low until about 2005. So for about a twenty-year period, from 1985 to 2005, we had cheap oil, which stimulated the global economy tremendously and allowed China, India, and other Asian countries to create the last great industrial economies, taking them out of the twelfth century and right into the twenty-first. It allowed the U.S. to enjoy the illusion that it was hugely productive, an illusion fortified by the computer revolution.

The rapid developments in computer technology encouraged overinvestments in scale and complexity, with diminishing returns. Computer-programmed trading prompted the financial wizards to concoct enormously complex algorithms for tradable financial instruments: namely, the alphabet soup of mortgage-backed securities, structured investment vehicles, credit-default swaps, and so on — the very things that helped get us into this financial crisis. Among the effects of hypercomplexity in finance was lack of transparency, meaning that these financial products were hard to value. They were designed to be as incomprehensible as possible, so that people couldn’t really know what they were buying. These fraudulent investments were sold to institutional investors all over the world. Pension funds in Norway were swindled into buying American mortgage-backed securities and went bankrupt as a result. This fraud spread around the world and basically wrecked the banking system.

Goodman: You’ve called our postindustrial economies “bullshit economies” because they’re not based on the production of anything “real.” But isn’t there a way to build an economy based on ideas, or services, or information, or intellectual property?

Kunstler: I think you can do it for a while, but always with diminishing returns. Geopolitical realities are such that you can’t assign various pieces of a global economy to individual nations on a permanent basis and expect to be secure. You can’t have all the manufacturing in Asia, all the paper shuffling in the U.S., all the banking in London, and all the tourism in Europe. Nations and cultural groups need to have more-balanced economies. If you import all your food, sooner or later you’re going to get into trouble. In the U.S. we’ve offshored all our manufacturing, so if we can’t afford to have products shipped to our doorstep, or if China gets pissed off at us, we’re in trouble. And sooner or later something is going to break down with trade relations, or shipping corridors, or the price of fuel, which is how wars start.

Another reason why I say we have a bullshit economy is that for about twenty years much of the so-called wealth we generated was based on housing prices going up, so people could use their homes like ATMs, borrowing against their value to buy more stuff. We had a so-called consumer economy based on easy credit — essentially financed by the rest of the world — which enabled millions of noncreditworthy people to get into the housing market, driving up the price of housing and leading many to believe they were wealthier than they were. And most of us could think of nothing better to do with our wealth than buy cheap plastic crap from China — pallet-loads of SaladShooters and flat-screen TVs. We let our cities and towns and schools and infrastructure and local retail economies disintegrate, but we didn’t care, so long as we could drive our SUVs to the mall.

Goodman: President Barack Obama isn’t saying the things that you are. Why do you think that is?

Kunstler: I voted for Obama and regard him as a person of high quality as far as politicians go, but I’m a little appalled at his actions thus far. He’s trying to revive a credit economy that very likely cannot be revived. We can’t return to an economy based on people buying goods with money they haven’t earned, and yet everything the administration is doing seems bent toward that end — especially its support of the big banks and the idea that if only we could revive lending, everything would be all right. But America is lent out. Too many households are up to their eyeballs in debt and can’t assume any more to buy cars or houses at the moment. And that’s only part of the broad spectrum of complex systems that will be affected by the end of cheap oil, including business, agriculture, transportation, construction of all kinds, and the way we do commerce, which favors national chain stores that enjoy huge economies of scale.

But these economies of scale are disappearing. Wal-Mart, which epitomizes the handful of predatory, opportunistic corporations that have wrecked our local retail economies, has succeeded because certain mechanisms in its business formula were made possible by cheap oil. For example, Wal-Mart has its famous “warehouses on wheels” — tractor-trailer trucks circulating incessantly on the interstate highways. The goods are stuffed onto a truck at the California docks and go straight to the store in, say, Philadelphia — which eliminates real warehouses and all the personnel and management costs to run them. That’s fine until the price of diesel gets up to five dollars a gallon, because there goes the profit margin. Real fuel scarcities would be the end of Wal-Mart’s formula, period.

That’s bad news for Americans, because national retail chains are one of the complex systems on which we depend. They’re going to fail, and we’re going to have to rebuild local networks of commerce and supply and even manufacturing. My guess is we’re going to be making and buying far fewer products. Commerce is going to be a much smaller-scale activity than we’re used to. Less consumerism and more local commerce are good things in the long run, but getting from here to there will be difficult and tumultuous. We have no idea how we’re going to reconstruct our local economies. It essentially means rebuilding our Main Streets.

Thomas Friedman of the New York Times sold the idea, which has become conventional thinking, that the global economy is now a permanent feature of the human condition. This is false. Globalism came into being because of special circumstances at a unique time in history — about a half century of relative peace among the great powers and many decades of relatively cheap energy. The twelve-thousand-mile supply line from Chinese factories to the American chain stores is a special condition, not a permanent arrangement. It allowed China to create a middle class, to electrify a lot of its rural areas, and to build a lot of spanking-new cities. The Chinese built the last great economy of the fossil-fuel age and had quite a time doing it, but it may not last very long. We’ll soon leave the fossil-fuel age behind, and we’re already beginning to see friction between the U.S. and China. The way we’ve run our finance sector off the rails has endangered their investments in our bonds. This is bound to affect our trade relations. And China is having internal problems, as well. I think the developed nations are going to retreat back into their respective corners of the world, and life is going to become a lot more local again.

Goodman: But our leaders keep saying we can’t go back to localism and protectionism; that we’ve got to keep our borders open, or we’re just going to exacerbate the financial crisis.

Kunstler: There’s a great fear that we can’t undo the economic relations built up over the last thirty years, and it’s understandable. I mean, once you’ve set all this machinery in place, you want it to work. There’s a phenomenon called the “psychology of previous investment,” which means it’s difficult for us to consider the possibility that something we’ve invested heavily in won’t work. But eventually it becomes obvious that we’re desperately trying to sustain the unsustainable.

Saying there is plenty of oil in the ground is misleading. The earth does not have a creamy nougat center of oil. Oil is found in a limited number of places and isn’t equally distributed around the globe.

Goodman: OK, but you can’t pick up a weekly news magazine without seeing a full-page ad from an oil company saying that there’s plenty of oil and natural gas out there, just waiting to be discovered.

Kunstler: Well, there is a lot of oil out there, but we also use so much of it, particularly in the developed parts of the world, that we have to keep producing more every year. Eventually you’re producing as much as you’ll ever be able to. After that peak, supply declines, and the world has to ramp down its oil use instead of ramping it up, which means more competition over supplies, not to mention problems with finance, debt, and money in general.

So saying there is plenty of oil in the ground is misleading. The earth does not have a creamy nougat center of oil. Oil is found in a limited number of places and isn’t equally distributed around the globe. Offshore deposits tend to be an extension of the onshore deposits. Some people think if we drilled for oil along the Atlantic Coast, we’d find a bonanza. But there’s no oil in North Carolina or Delaware or Georgia, so it’s unlikely there’s any oil off the continental shelf east of those places. The ANWR field, in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, contains about three months’ worth of oil at the rate we currently use it. I’m not even against drilling in ANWR, because I believe we could do it in a pretty sanitary way. But it wouldn’t make much difference. The idea that we can drill our way out of this predicament is a delusion, one of many the American public is entertaining right now.

Goodman: Won’t demand for oil and gas decrease as they become more expensive?

Kunstler: The question of oil demand really hinges on how badly the complex systems of our society destabilize. Prior to 2008 many peak-oil observers believed that the years ahead would behave like an economic “bumpy plateau,” with high oil prices dampening economic activity to the extent that oil prices would come down, at which point cheaper oil would restimulate economic activity. It didn’t work out that way. In the first high-price cycle, the banking system was effectively crippled (perhaps even destroyed; it isn’t clear yet). Right now we’re still reeling from the sudden disappearance of capital, which is affecting all our systems, from trade to transport to agriculture.

It’s been devastating to the oil industry itself, with new projects getting canceled, which means even less ability to offset future depletion. The social and political implications are pretty dire. If our leaders don’t guide the public to think more realistically, we’ll end up in a tragic situation. It’s imperative that we direct our remaining resources — material, psychological, and spiritual — at a comprehensive downscaling of American life. Reality is going to force us to do it anyway.

We’re going to have to grow our food differently, because petrochemical agriculture is going to fail us. We’re also going to have to inhabit the landscape differently, because suburbia is going to fail us. We’re going to have to return to walkable towns and cities, smaller and more modest than we’re used to. Cities like Dallas and Atlanta are going to have to contract, whether they like it or not. But there will be benefits to this, too. Compact urban areas are much more fulfilling and rewarding to live in. That’s one reason people take vacations in Italy and France, because those countries have retained the principles of good urban design. Americans go there, love it — and then come home and do everything possible to destroy their own towns and cities.

But that phase of our history is over. We have no more capacity to suburbanize. We’re going to have to return to local commerce, and there will be many benefits. Local retail economies will employ a lot of people and afford us more control over our commercial destiny. Before the big-box stores took over, a business owner would take care of his or her property, because the business owner lived in town. When you eliminate those people from the economy, you eliminate the caretakers of the downtown buildings. It’s no surprise that when you go to small American towns today, you find a shiny Wal-Mart and a Target by the highway, and the rest of the town is in a shambles, because there are no local businesses taking care of it. We wrongheadedly and tragically developed the idea in the U.S. — abetted by the big-box stores themselves — that bargain shopping is of absolute importance, and we threw away our towns in the process. But the big-box model will fail, and we’re going to be forced to reinvent local networks of economic interdependency — which doesn’t mean we’ll be miserable. It just means we’re not going to be shopping in stores that are two hundred thousand square feet, and Wal-Mart executives and stockholders aren’t going to be getting rich at the expense of everyone else.

And, by the way, I’m not a socialist. I’m the farthest thing from one. But I believe citizens should be in control of their town’s destiny, and we haven’t had that for the last twenty years in the U.S.

Goodman: Right now, in mid-April 2009, the stock market is going back up, but I suspect you’d encourage us not to see this as a sign of recovery. If we aren’t getting accurate readings about our situation from the price of oil, or the state of the stock market, or from our political leaders, then how are people supposed to be aware that we’re in trouble?

Kunstler: That’s something I’m concerned about. What we’re seeing now is an economy running on fumes, on wishes, on hope, on the idea that if the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department create enough digital dollars, they will levitate this broken economy back up to full operation. But this is merely a wish. It may cause some recovery in the investment markets for a while, but jobs are still being lost in huge numbers, the price of housing continues to go down, and more and more people are underwater with their mortgage obligations. The cycle of deflationary depression is still very much in operation.

We’ll probably see a sucker’s rally, or a “bear-market rally,” in the stock market. But before long the air will come out of this rally, and we’ll find ourselves in deeper trouble. The bankruptcy of the banks and of our municipalities will become undeniable. The end of the consumer-credit economy will result in a permanently lowered standard of living, to put it mildly.

Goodman: What about alternative energy sources?

Kunstler: There’s a lot of wishful thinking that somehow we’ll replace fossil fuels with alternative energy sources, but they remain far from reality. We’re not going to run Wal-Mart, Disney World, and the interstate-highway system on any combination of alternative or renewable energy — solar, wind, algae oils, ethanol, used French-fry grease, you name it. We’ll try them all, but we’re going to be disappointed in what they can actually do for us, especially in terms of running things in the U.S. as it is currently set up.

There are plenty of things the Obama administration could be doing that it’s not. We’d benefit more from rebuilding the railroads than from pouring money into Goldman Sachs and AIG. We’re going to have a lot of trouble getting around this continent-sized nation of ours as the realities of energy scarcity assert themselves, and the airlines go out of business, and the whole mass-motoring system gets into difficulty.

Goodman: In The Long Emergency you say nuclear power plants might be our only hope for keeping the lights on.

Kunstler: If we want to keep the lights on after 2020, we may have to resort to nuclear power. At the very least, we have to generate a robust public debate about its costs and benefits.

Goodman: And if our society does unravel, how do we maintain security at nuclear power plants?

Kunstler: This is a problem. The more unstable everything gets in our society, the more difficult it becomes to maintain the levels of complexity we’ve achieved in all areas: security, finance, transportation, agriculture, commerce, medicine, education. You can describe the crisis as an across-the-board unwinding of complexity. All of these systems are getting into trouble. It turned out that the financial system foundered first. The next system to go could well be our food-production system, because it’s hyperdependent on both fossil fuels and credit. We don’t know yet, as we enter the planting season, whether the farmers in the grain belt are getting their loans. I don’t think we’ll hear about it for a while.

I recently spoke at the Aspen Environment Forum, and I found that the elite environmentalists of America are as misguided as their corporate sponsors. The only conversation anyone wanted to have in Aspen was how to run our cars by other means. To me that is the most foolish conversation possible. We need to be concerned about all these multiple complex systems that we depend on daily, not just keeping the cars running. Life is not just about driving around, no matter what the car is running on. We’re doing too much motoring, period!

I’m suspicious of the word solutions. When people complain to me, “You don’t offer any solutions!” I assume they are referring to a means by which we can keep living exactly the way we’ve been living, which isn’t going to happen.

Goodman: But, as you’ve pointed out, we’ve set up our towns and cities so that driving is necessary. There’s no other way to get around.

Kunstler: Well, it would require us to start making some serious changes, like promoting walkable communities instead of alternative-fuel schemes for incessant motoring. And unfortunately the elite environmentalists have bought into the system as much as anybody. At the Aspen Environment Forum nothing was said about public transit. We desperately need to revive the passenger-rail system in America, because the airline industry is not going to survive too much longer. They’re having a hard time when oil is fifty dollars a barrel; if it gets up to seventy-five dollars a barrel again, they’re done. They’re not going to exist as we know them. After a certain point, flying will probably be an elite experience. We need to have a railroad system that works, and the fact that we’re not talking about this gets back to the comprehensive failure of leadership.

It’s not just political leadership; it’s leadership in business, in the environmental sector, in the academic sector. The architecture schools don’t want to address our need to inhabit the landscape differently. We’re going to have to return to traditional, walkable urbanism, but all the architecture schools want to talk about is one-off signature monuments that are narcissistic exercises in attention seeking. They’re not interested in the larger picture of how we design and assemble human habitats. Among other things, they don’t see that the skyscraper may soon be obsolete. We have no idea how we’re going to keep tall buildings warm in a fuel-shortage situation. The only two things we could possibly switch to right now are nuclear power, which we have had an insufficient public debate about, and coal. And coal is probably not going to be as reliable as some people hope, not to mention its contribution to climate change. We’ll never be able to renovate many of these huge buildings as they reach the end of their design life.

People believe that technology is going to rescue us, allowing us to keep everything running by other means. I call this “techno-triumphalism.” Oil is much more special than people realize. The amount of energy locked up in it is enormous, and we’re not going to compensate entirely for its loss. There’s a lot we can do with renewable energies, but it means we’re going to have to downscale substantially, and this is not part of our game plan.

Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not against alternative energy. I just think we’re going to be disappointed by how much it can do for us. We simply can’t generate the number of BTUs necessary.

Goodman: What about energy conservation?

Kunstler: You can pay lip service to conservation in the suburbs, but the suburbs are what they are. They are designed to work on oil and gas, and we’re kind of stuck with them as they are. The Jolly Green Giant isn’t going to move the shoddily built, energy-inefficient houses closer together. Our choice is either to fight the inevitable failure of these places or to get serious about reinhabiting the older parts of our existing towns and cities. Where I live, in a former industrial region of the upper Hudson and Mohawk valleys, the existing traditional towns and small cities have been completely deactivated, but they’re much more appropriately scaled to the energy future than the big metropolises of Houston and Dallas and Minneapolis. I think we’re going to see people moving back to the smaller cities and towns, especially places that are near inland waterways and water supplies generally. I think the rural places are going to be inhabited differently, because farming is going to require more human attention.

There’s one huge element to alternative energy systems that we tend to overlook: our ability to develop them requires a fossil-fuel platform. I’m not sure you can even operate — let alone build — a nuclear power system without oil and gas to run it and service it. The fantasy that we’ll put up “wind farms” assumes that we’ll be able to manufacture thousands of these four-hundred-foot-tall turbines. That’s going to be problematic. You need to be able to mine the metals, run the fabrication facilities, transport the pieces, and lift them into place. And you need to keep the replacement parts coming. People who think we can just build these giant wind turbines and get free energy are to some extent hoping that you can get something for nothing. You need an oil-and-gas industry to support that kind of endeavor.

Goodman: Do you think the failures in the financial system might buy us time, if we had the leadership to use that time to develop a new economy?

Kunstler: Your question doesn’t take into account the social and economic disorder introduced when the financial sector gets into serious trouble. I hear two themes that both represent a big fantasy. One is the techno-triumphalist fantasy that assumes we’re going to invent our way out of our problems: some mythical “they” will come up with a techno-rescue — a new miracle fuel to keep the cars running, or something like that. The other fantasy assumes that we’re going to organize our way out of this mess. Both tend to ignore the likelihood that we’re going to be living in a more disorderly society with a lot of people who are unhappy and perhaps violent and who are going to be making disruptive political claims.

That’s why I think a certain modesty is in order as we set about downscaling our systems. Grandiosity is not a good attitude to bring to this venture.

Goodman: Do you see any models out there we can look to for guidance?

Kunstler: Some cultures have developed more-satisfying living arrangements than the American suburb or the skyscraper. Europe, for example, has exemplary walkable towns and cities. Europeans did not destroy their public transit. People who live in Barcelona or Paris or Berlin can get where they want to go whether there’s gasoline available or not. They made different choices than we did.

Goodman: And their cities are surrounded by functioning farms.

Kunstler: Well, they made an effort to prop up local agriculture when we didn’t, and they appreciate many aspects of small farming that we have not valued. For example, Europe is renowned for making cheeses and wines, and Europeans appreciate that these products have a great deal of local character and that localities profit by them. In the U.S. you basically have two factories that supply all the taco cheese that’s sold in this country. So Europeans will already have local products when the world has to relocalize, and we won’t unless we get with the program pretty damn quickly.

Goodman: Can capitalism survive on a finite planet if it’s based on the idea of never-ending growth? People want their 7 percent, or 10 percent, or 20 percent return on their passive investments, no matter what the social or environmental consequences might be.

Kunstler: I don’t regard capitalism as a belief system. I regard it as a set of laws that govern the behavior of surplus wealth. That’s all. It’s a matter of how you produce that wealth and, when you have it, whether you save it or deploy it for productive purposes. What is a productive purpose? Rampant consumerism isn’t productive. It would be much more productive if the people of, say, Muncie, Indiana, rebuilt Muncie so that they could live there happily and produce things of value.

Goodman: I think people could get excited about devoting their energy to some meaningful purpose if only they had leadership that pointed them in the right direction.

Kunstler: I basically believe that, too. But first I think we need a coherent consensus on what is actually happening to us and what we might do about it. Right now we don’t have that. What we have instead is agreement about wishes and fantasies. There’s agreement that we ought to run the interstate-highway system with electric cars. That isn’t going to happen. There’s agreement that we could run our current commercial model on a combination of solar and wind and biodiesel energy. That isn’t going to happen, either. There’s no agreement that we ought to rebuild Hudson Falls, New York, and Muncie, Indiana. There’s no agreement on the need to change the way we do agriculture.

Goodman: But I think that’s because no leaders are articulating the need. I think we’ve got to raise the level of conversation, and agreement will follow.

Kunstler: Obviously I’m trying to influence the conversation, but I don’t have any grandiose fantasies about my chances of success. But I’m not the only one talking about these issues: there’s Richard Heinberg of the Post Carbon Institute (www.postcarbon.org); Dmitry Orlov, author of the recent book Reinventing Collapse: The Soviet Example and American Prospects; Nate Hagens, Robert Rapier, and Matt Simmons, all of whom write for the Oil Drum (www.theoildrum.com); and a long list of other clearheaded people.

Goodman: Are there groups or organizations who are proposing solutions?

Kunstler: I have a lot of respect for the Oil Drum website and the Post Carbon Institute, but I’m suspicious of the word solutions. When people complain to me, “You don’t offer any solutions!” I assume they are referring to a means by which we can keep living exactly the way we’ve been living, which isn’t going to happen. I prefer to talk about “intelligent responses.” Some conditions are going to have to be endured rather than vanquished, such as a drop in our standard of living. There’s no solution for that, but there are plenty of intelligent responses. You can learn to repair your own clothes, grow your own food, make your own music. There are all kinds of things you can do, but they’re not necessarily “solutions” to the problem.

Goodman: What else can people do to minimize the suffering they might otherwise have to endure?

Kunstler: If you live in the suburbs, you could sell your house, even at a loss, and relocate to a place that has a future. If you’re a mortgage broker or work in the financial industry, you might consider whether there’s something else you’d rather do with your life. You won’t make as much money doing it, but maybe it will be rewarding in other ways. You might buy ten acres of land and start growing table greens, become a paramedic, or find some other focus for your energy that would make you useful to your fellow human beings during the coming crisis. Probably the worst thing we can do is sit back and hope other people will sort it all out for us, or that things will remain stable enough that we can keep going to our corporate jobs and commuting to our single-family homes.

Goodman: You mentioned possible benefits that might come about as a result of this massive downscaling. What are some of them?

Kunstler: Working in your garden is physically demanding, but having to work harder physically would surely benefit an American public that is overweight and has developed multiple chronic diseases as a result of inactivity. And Americans may eat more healthily and spend less money on canned entertainment and more time with their families. They may find making music more fulfilling than playing video games.

Goodman: Perhaps the breakdown of everything that isn’t working could be an opportunity for new grass-roots organizations to take hold — sort of like a forest fire making room for new growth.

Kunstler: Sure. In nature, after some catastrophe, new organisms emerge to take the place of the old ones. Our systems may fail, as they have in other civilizations before ours, and we’ll go through a period of disorder, but we’ll reorganize and live differently.

The rise of industrial societies has been pretty spectacular because so much energy was introduced into the system in a relatively short time: a couple of hundred years of fossil fuel. It remains to be seen what new social order we’ll create after industrial society’s fall.