In the spring of my seventh-grade year, I came down with a resilient but otherwise unremarkable case of bronchitis. One night I was having trouble breathing, and my mother took me into her bathroom and turned on the shower as hot as it would go. Standing in that foggy bathroom, inhaling big lungfuls of steam, I got a crazy idea: I would stop breathing.

After a moment I waved my arms in a distress signal. My mother remained calm at first. She swatted my back a few times, the way mothers do. Then her face grew worried. I took a breath.

“What happened?” Mom asked. “Are you all right? Were you choking?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “My lungs just sort of locked up.” I waited a few beats for dramatic effect and then stopped breathing again. This time I added a hitching movement in my chest. No sound; just hitching.

Keeping her displays of terror to a minimum, my mother drove me to the emergency room, where I practiced my form in the waiting area. I decided to make the attacks a manageable forty-five to sixty seconds in length (although on occasion I went for as long as a minute and a half), and the hitching became more of a spasmodic jerking. The entire room was captivated by my performance.

Once in a hospital bed, I displayed my shocking symptoms for an assortment of doctors and nurses: First my chest would hitch once, like a hiccup, and my breathing would cease. Then I would widen my eyes and roll them back and forth, as if alarmed. I’d randomly contract my chest muscles and cause my limbs to twitch and shake.

Within a couple of hours, I’d been subjected to blood draws, vital-sign monitors, and a metal probe that was shoved down my mildly anesthetized throat. One doctor finally suggested that I might be making the whole thing up.

Outraged, my mother transferred me to another, better, hospital across town.

To my chagrin, I was placed on the pediatric ward. I would have preferred to be in with the dying patients. But I had faith that if I continued to display my symptoms in a convincing and consistent manner, the doctors would have no choice but to bump my status to “critical.” I really was quite sick. In addition to my bronchitis, I’d developed a high fever and a propensity for vomiting that I used to my advantage.

I was king of my own small kingdom. When a clown came into my room, under the misconception that balloon animals would cheer a twelve-year-old, I simply conjured an attack, and he was out the door in an instant. If I wanted my mother to stay by my side, I maintained a worrying regimen of five or six attacks an hour. If I wanted her to leave me alone, I scaled back the spasms and said, “I’m feeling sleepy.” It worked every time.

One day a doctor came in to prepare me for an MRI. I’d never had one before, and I asked what they would be looking for.

“Mostly brain tumors,” he casually informed me.

I was positively delighted. I told every visitor that the doctors suspected brain cancer.

Several days later, with the doctors still befuddled, my mother decided to do some research of her own. She concluded with near certainty that I was having an allergic reaction to the cough medicine I’d taken. When she told me this, I affected fascination and relief, though I secretly wished for a more dramatic cause than cough syrup.

After about a week in the hospital, my fever and bronchitis had cleared up, and I gradually reduced my attacks until they “vanished” altogether. The doctors were apprehensive about letting me go, but my mother insisted, and I was allowed to return home.

To this day, my mother warns me to stay away from Robitussin.

Name Withheld

When my twin daughters were infants, I often referred to them as my daytime baby and my nighttime baby. Lily couldn’t bear to be out of my arms during the day, and Shira needed to cuddle at night. When my husband and I finally nudged them out of the family bed at the age of four, Shira lamented, “I don’t like getting older. Everything changes.”

As glad as I was to have access to my husband, I missed snuggling with the girls. But I held firm and explained to them, “A mommy who doesn’t sleep enough is a crabby mommy.” I told them not to wake me unless they were sick or had had a very bad nightmare. And I praised them lavishly when they made it through a night without calling for me.

One night I lay in bed and heard Shira whimper. Hoping she’d fall back to sleep, I didn’t go to her. Then a tiny voice called out quietly, “Mommy?” She was trying to be good. Though I wanted more than anything to gather her into my arms, I lay still. A rule is a rule, and I knew I would lose much ground if I gave in.

The calling stopped. Good. Maybe she’d gone to sleep. Then I felt the covers being carefully lifted, and, with a degree of stealth that must have been very hard for a four-year-old, Shira climbed into my bed. She edged toward me until we were just barely touching. I pretended to be asleep and breathed in her sweet smell. There would be time enough in the morning to remind her that big girls sleep in their own beds.

Robyn Samuels

Tarzana, California

I cheated on Matthew with Henry, on Bill with Ethan and that boy from Berkeley (what was his name?), on Steve with Ron — until I returned home one morning to find Steve dumping my belongings in the front yard. I cheated on Daniel with Heather. I cheated on Susan with Craig. I had sex with a man four hours after responding to his personal ad. He was an attorney and made jokes about the pedophiles he’d defended. As he was taking off my shirt, I thought, I don’t even like you. But the only thing I didn’t let him do was come on my face.

I contracted herpes, but I didn’t tell my partners until after I’d had sex with them, if then. I believed that I was brave and free and had thrown off patriarchal constraints on my sexuality. Really I was reenacting the patriarchal structure of my childhood home. My angry and distant father once punched my sister in the stomach for having spilled milk. Another time he threw my crying brother against a bunk bed.

Dad seemed serene only when he noticed a beautiful woman. He’d comment on what he found sexually attractive about her. “She has very good-looking legs,” he’d announce, as if revealing a fierce truth. I learned there was only one way to get positive attention from a man.

For me sex was a way to win affection from people who didn’t really care about me. It afforded me a certain victory, even when I lost my dignity.

In graduate school, I became friends with David. After graduation, he and I left for different cities, but we stayed in touch. He was a delightful pen pal, clever and funny. I would sit in the sun and savor his letters (this was before e-mail) and carefully compose a response.

The first time I went to visit David, we steamed up the windows in his apartment. The next day he called to confess that he hadn’t enjoyed the sex. He was sorry he hadn’t stopped to tell me. “I wasn’t really in my body last night,” he said.

I was strangely relieved by his admission, and eager to make one of my own. “I wasn’t entirely honest with you either,” I said. “I have herpes.”

He was silent for a few seconds, then said, “That’s not what friends do to each other.”

He ended our relationship. I was paralyzed by depression for weeks.

A few years earlier, a therapist had suggested I try a twelve-step program. I went to my first meeting in a dimly lit room above a West Hollywood cafe. Five men sat in a circle, looking sad and lonely. I didn’t want to think I was like them. What am I doing here? I thought as I took a seat.

A young man with gentle eyes spoke first: “Hi, my name is Martin, and I’m a sex and love addict.” He said he was HIV-positive and had slept with more than a thousand men.

My tears started and would not stop. Martin was me — a different gender, a different person, but me nonetheless.

I struggled to lead a sexually honest life. For starters, I told all prospective partners that I had herpes. To my surprise, this did not deter many of them. But I still had sex with strangers. I still lied — to my partners and to myself.

One day it dawned on me: I had to limit myself to sexual behaviors that I would not be tempted to lie about. I am embarrassed now at how obvious this seems, but at the time it was a revelation. I decided that, when faced with the possibility of having sex, I’d ask myself, Is this something I will lie about later? If the answer was yes, I wouldn’t do it.

This practice has cleared up a lot of my confusion. It’s as if some peaceful part of me is floating just above the scene, gazing down with compassion — and do I want to lie to her?

Name Withheld

When I was growing up in the seventies, I did drugs but avoided heroin. Everyone knew that when it was time to fix, a junkie would tell God a lie.

In 1991, after a year on parole, I hit a tough streak and began smoking crack. An acquaintance showed me how. My swift descent into addiction was predictable, but my newfound ability to lie caught me by surprise. My bosses wondered where my delivery money was. My eighty-six-year-old grandmother was amazed that new tires cost so much. Within a year I had burned everyone I knew, smoked all my possessions, and dropped thirty-five pounds. I had one goal in life: another hit.

As I drove away from my second armed robbery in twelve hours, headed for the “dope hole” in a freshly stolen convertible, I burst into laughter. Outright stealing felt like the most honest thing I’d done in years. No more lies. It was such a relief.

John Kingham

Bowling Green, Florida

In high school I was involved in student government, had major roles in school plays, never dropped below a 3.2 grade-point average, and was elected to speak at my graduation. I was even voted “Best Sense of Humor.”

I loved school. Really it was not so much school I was in love with, but the other students. Geeks, jocks, stoners, cheerleaders — they all fascinated me. I ached for some deeper connection with all of them.

Yet at some point every day I would be gripped by the fear that someone would find out I was a fraud. Once people realized I did not deserve this happiness, it would all come to an end.

On the way home, I would become “Dumps,” the nickname given to me by my stepfather. My shoulders slumped, and I scooted silently around the house, absorbing everyone’s cruelty like a kicked dog.

Before my parents had divorced, my birth father used to corner me in a room and threaten me with a backhand until I cried. Disgusted by my tears, he would then deliver a brutal spanking for “being weak.” By the time I turned six, there was nothing he could do to make me cry.

Although I doubt they suspected what had gone on, my mother, my stepfather, and my siblings unconsciously followed suit with a stream of verbal hostility. Perhaps I even encouraged them. It was the closest thing I knew to intimacy.

I was not allowed to have friends over or to attend most social functions, so I sneaked out my bedroom window several nights a week. I didn’t make much at my part-time job, and I couldn’t ask my parents for money, so I shoplifted most of my clothes. By the end of my senior year, I’d stolen thousands of dollars’ worth of merchandise. My family never noticed.

I dutifully produced report cards but hid any awards or certificates I received. I lied about play rehearsals, saying I’d been at work or the library. At home I’d drink stolen alcohol in my room and write love poems to a boy who did not love me back. If I felt particularly bad, I would cut my torso with a knife, being careful to cut only places my bra would cover. Then I’d paint my face with the blood.

Don’t ever idealize the homecoming queen. She could be me.

Jeanne L.

Ibaraki-Ken

Japan

I don’t think my boyfriend of four years has ever met the real me. I swear to him that I don’t like clothes that are too revealing. I insist I don’t listen to raunchy rap music. I deny that I find other men even remotely attractive. I lie because I want him to think I’m special, not like every other girl out there.

He is the only person I’ve ever slept with. At least, that’s what I tell him.

Name Withheld

My father taught me that it was OK to lie, and that people who didn’t lie were idiots who would suffer for playing by the rules. “Look at that poor Joe Burns bastard,” he would say. “Never cheated on his taxes, never cheated on his wife, and look what happened: his wife left him and took every dime he had — and then he was audited!”

“It’s a tough world” was my father’s mantra, and “If you don’t screw them, they’ll screw you.” It’s a persuasive argument when you’re five years old and your drunken father keeps a loaded gun under his pillow.

After I became an adult, my father called me one night with a proposition: He had bought a used Audi that turned out to be a lemon. He wanted to transfer the title to my name and then report the car stolen. It would become a “Tijuana taxi,” my father said. We would split the insurance money. I told him I wasn’t interested in risking a felony so that he could make a couple of thousand dollars. He hung up in a rage, but not before saying, “Some daughter you turned out to be.”

It took me many years to realize that my father had no ethics, and that my own were often questionable. These days the worst thing I do is try to reuse bus transfers.

Shannon M.

Seattle, Washington

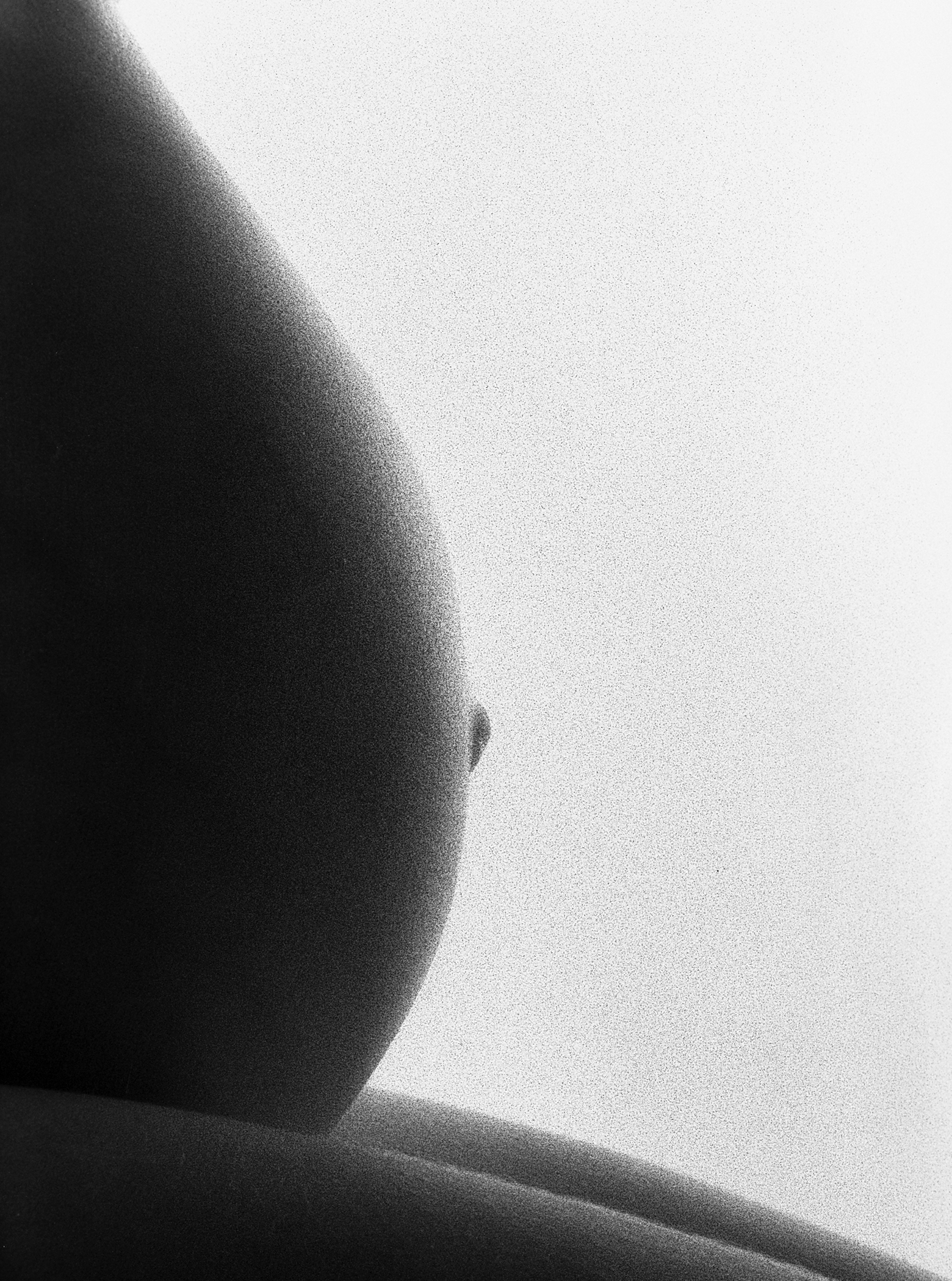

My husband and I were planning a home birth, which made my in-laws nervous. Oh, they didn’t come out and say it. But their doubts were plain in their taciturn responses when I told them about my midwives and the birth cottage.

The birth was hard, the antithesis of the relaxed, spiritual event I’d expected. When I saw my son for the first time, I felt drained, raw, and near dead.

Enter my pushy, judgmental in-laws, anxious to hear how horrible it had been, how wrong I’d been about the whole thing, how glad I would be to have the next one in the hospital, with an epidural and doctors surrounding me. “You can sit and watch TV through the whole thing!”

I did not satisfy them. I lied. I said it had been wonderful, that my husband had been more traumatized by it than I. (He’d thought I was dying.) I said it had been a little harder than I’d imagined, but the pain had been manageable, and only the last half-hour or so had been really rough. I told them I wanted a home birth for my next child.

Later, as the doctor was stitching me up, he accidentally hit a spot with no anesthesia, and something inside me snapped. The truth came out with the tears: It had been awful. I’d hated it. I would have begged for drugs if I’d been at a hospital. I sobbed and held my midwife’s weathered hand. The doctor looked confused. I was ashamed of my weakness and angry with my body for not having cooperated in letting me have the birth experience I’d wanted.

My husband is proud of me, but the truth is, my continued dedication to home birth is pure obstinacy. I wish I could be honest about the pain, the exhaustion, the feeling of hopelessness I endured. But I can’t. I want to be right.

Emily Arnold

Sevierville, Tennessee

All the children in my large Irish family attended Catholic school, where we were taught to handle pain, whether gnawing hunger or a parent’s angry slap across the face, by “offering it up for the poor souls in purgatory.” I believed whatever hardship I endured would not only save someone else’s soul but also hasten my own journey to heaven.

My faith helped me cope with my mother’s undiagnosed manic-depression. I obsessively recited novenas that promised miracles if performed correctly and with devotion. I believed the priest’s assurances that if I prayed diligently, sacrificed, and accepted God’s will, my mother would know peace.

I was twelve years old and home alone with my mother when she attempted suicide. After failing to reach my father and my grandmother, I called an ambulance and then the parish priest. The ambulance came and went, and I waited on the front porch for Father M. to show up and comfort me, reassure me, lift the burden of responsibility.

When Father M. arrived, he asked if my mother had still been alive when the ambulance had left. I said I thought she had. “You know,” he said, “if she dies, she cannot be buried in a Catholic cemetery. Suicide is a mortal sin.”

While my mother recovered, I struggled with the realization that I would find neither compassion nor comprehension in the teachings of my church. I began to seek insight at the public library instead. But my parents still expected me to attend church.

I left the house by myself each Sunday morning, telling my parents that I was going to early Mass because I wanted the rest of my day free. I walked to the doughnut shop a few blocks from the church, drank a cup of cocoa, and perused the day-old newspapers. Walking home an hour later, I composed a plausible theme for the morning’s sermon, in case I was asked. My fictional accounts seemed to bring my mother peace of mind.

Susan Haines

Anchorage, Alaska

I was thirty-three and pregnant with my first child when I developed a strange, severe itching on my feet and hands. My doctor asked whether I had any Swedish heritage.

“No,” I said with a laugh, “I’m an Eastern European Jew!”

Nevertheless, my symptoms pointed to a rare disorder found most often in the Swedish population. Although my mother and I had been estranged for years, for the sake of my baby’s health I called to ask her if there was any Swedish ancestry in our gene pool.

“No,” she said, “no Swedish, and I had no problems like that with any of my pregnancies.”

My doctor did the blood test anyway and found that I had the disease. They induced labor a month early to save my baby’s life. Fortunately she was born healthy and strong.

My father had died three months before my daughter’s birth, and I spent the first few weeks of her life scanning her little face for signs of his. I found none. No sign of my mother’s features, either. My daughter is blond with bright blue eyes. I joked to friends and family about my putative Swedish ancestry. In private, however, I found her appearance somewhat alien. She did not look like my family, and she didn’t look much like my husband’s parents, either.

Eighteen months later, I learned that I’d been adopted at birth. Almost everyone in my family knew. I thought of my father’s funeral, how I’d delivered the eulogy, speaking at length about our Jewish ancestry. No one had said anything.

Now I dread the approach of Yom Kippur, the day on which my religion commands me to forgive. Some days I walk around cursing my family, as if in a bad Shakespearean monologue. On better days, I feel lucky not to be related to these people who would have let my baby die rather than tell me the truth. Sometimes, for brief moments, I feel sorry for them. How exhausting it must have been to sustain such a lie for so long.

While searching for my birth parents, I discovered that my older sister, too, was adopted. She does not know. I hesitate to tell her, although I must. These lies are a family tradition that I refuse to keep.

Ivy G.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

From the outside, Ben and I appear to be a great couple, blessed with two smart girls, gainful employment, good health, and a passionate relationship. We skate, we bike, we argue heatedly, and we support one another’s differences.

One night a week Ben works at his art studio — his only escape from the overload of female energy at our house. At home, he is often left out of our discussions, sadly shaking his head as we girls proceed to agree on almost everything. At the studio he and his friends can make art, drink beer, and play darts into the wee hours. This one night to himself always makes him happy, at least briefly.

He’s always asking me to join him, but most weeks I’m bogged down at home with work or parenting duties. While Ben is away this summer, I decide to go to the studio and work alone — something I know he’d encourage me to do.

When I arrive at the studio, I check the answering machine and hear an unfamiliar voice, slightly desperate, very seductive: “Hi, baby, it’s me. Hoping to catch you. I really need to talk to you. Call me as soon as you can.”

Who the hell is “me”?

The room is slowly spinning as the next message plays back: “Hey, sweetheart, it’s me again. I really need you to help me out. Just as one, um, friend to another. Call me, ASAP.” Beep. “Ben, hi. Why aren’t you calling me? Oh well. Love ya. It’s Tuesday.” Beep. “Hi, it’s Tuesday” — I realize that Tuesday is her name, not the day.

Then I hear a new voice: “Hi, Ben, this is Treasure, and I’m in town. I’m hoping you’d like to make an appointment with me. I’d love to see you.”

The bottoms of my feet are tingling. These aren’t girlfriends: he’s buying sex. I think of all the times he didn’t answer the studio phone and later gave me some excuse: “Oh, I was at Jim’s house playing darts.” “I was in the yard, then I had to get gas.” And he’d tell me how “silly” I was for being suspicious or insecure.

I step back and examine my reaction, to be sure I’m not being prudish. Nope. As a matter of fact, I have explored the world of porn and become undeniably, uncomfortably aroused at the thought of a threesome. But how dare he explore other partners without me!

I confront him, and the truth seeps out. I feel as if I’m bobbing in some vast body of water with no land in sight. Do I kick him out? Is he sick, or just crazy? Am I a complete fool to think we can survive his paying for sex fifty times (his estimate) in less than a year? Weekly visits with a couples counselor barely take the edge off my anxiety.

They say the deeper you go into a crisis or tragedy, the sooner you come out the other side. So I devise an exorcism plan: I have kept Tuesday’s number (most of the messages were from her), and I call her, posing as a writer. I ask if she’d be willing to have coffee with me, to talk about her “business.” No cameras, just me and my yellow pad. I’ll pay her for her time.

She laughs and says she’ll meet me at Denny’s. She’ll be the only one wearing tall black boots in eighty-five-degree weather.

At the restaurant, I glimpse Tuesday through the window and guess immediately that she has a drug problem. She jiggles her crossed legs like a nervous schoolgirl. As I approach, I smile as sincerely as I can, but my brain is filled with nasty images. She says she’s starving, and I tell her to order whatever she wishes. She downs two cups of coffee before I’ve even sipped my water. Then she asks if I’m from some religious group that tries to save people like her. What you don’t know! I think.

I ask my questions, pen poised, trying to look professional. Tuesday takes over the conversation, telling me how stupid most women are: “If they’d just let their men go crazy in bed and do what they want, I wouldn’t have a job.”

“You think it’s that simple?” I say.

“Oh, honey, a lot of them never get to really look at a woman all spread out, and that’s what so many of these guys want to do — beat off and watch me do the same, like having one of their horn-dog magazines come to life. How hard is that?”

I know that’s one of the things my husband paid her to do, and the bile rises in my throat.

Then I arrive at the question I’m most afraid to ask: “Do you practice safe sex?”

She laughs and says, “Are you crazy? I may be a dope fiend, but I don’t got no death wish. I don’t know who these guys have been with or what they do with the rest of their time. I use condoms even for blows.”

I come to the other question I’m anxious about: “Do you actually talk? Do they talk about their wives or girlfriends?”

“Oh, sure, but mainly I just tell them how goddamn sexy they are. I’d say most of them don’t hear that at home.”

After a few more questions, I tell her that I think I have enough to go on. She wants to know where she can read about herself and asks if she can choose a pseudonym. “I’ve always liked the sound of Lulu. Can you call me that? I don’t want my tricks to get upset that I’m talking about this.”

I tell her that’s fine. As I stand on my wobbly legs, she grabs my arm and says, “You got a guy?” (I took off my wedding ring before the interview.)

“Yes.”

“Well, honey, you’re hot. You should get out of those hippie clothes and dress more sexy. I bet he’d like that.”

Name Withheld

I faked it for more than twenty years of marriage: Not sex. Religion.

Before we married, my husband practiced his religion in private, but several months after the wedding he brought his Muslim faith out into the open. Each day he performed the ritual washing ceremony, spread out his prayer rug, placed his stone upon the small carpet, and murmured his prayers.

A year later, my in-laws came to the United States for an extended visit. My father-in-law asked why I did not perform the daily prayers.

It wasn’t difficult to memorize the Arabic. At first I knew what the words meant, but after a while I forgot their meaning, and the prayers became just a jumble of sounds I didn’t understand. How can this be pleasing to God? I thought. When my husband wasn’t around, I would skip the prayers and just rumple up the chador I wore when praying, lest he notice that the garment had not been used.

After we divorced, I concluded that people can keep God in their hearts without uttering a word. They can also whisper words of prayer thousands of times without really comprehending them — even when they have been born into the religion.

I may have deceived my husband, but God knew what was in my heart, and he forgives me.

Carol Robideau

Oakland, California

In my youth I had love, passion, and a natural talent for art. I was rebellious and true to myself, and always said what I believed.

I have become the stereotypical suburban housewife and mother, an Oprah-watching, women’s-magazine-reading fool who nods politely while her husband cheers the war coverage as if it were a football game. We even have a big-screen TV with surround sound on which to watch it.

Who is this woman who voted for a president who thinks tax cuts are more important than helping single mothers on welfare? Who is this pushover who lets her mother-in-law next door tell her how to decorate, how to raise her children, and how to be a good wife? What happened to the girl who would have told the old bag to kiss off, or at least to call before she came over? Where is that creative girl who preferred to paint all day rather than make the house tidy and clean, who cranked up her funky music and twirled around the room and sang off key? What happened to that young woman who was more concerned about the environment than driving the latest SUV; who would have had the guts to leave a man with no compassion?

Name Withheld

It starts when you are twelve and thumbing through your dad’s Playboy. You are shocked by the abundance of flesh. When the moisture seeps through your panties and you touch yourself, a voice whispers that you are sick, a pervert. So you put away the magazine, and your desire, and promise never to do it again.

You are seventeen and lying on your best friend’s bed in the middle of the day, drinking and watching her parents’ porno movies. You laugh at the positions and the grunting, and pretend to admire the guys’ big dicks. You brag about your boyfriend, how he came in your mouth and you swallowed every drop; you tell her you loved it, though the semen tasted like warm baking soda and you had to count to ten to keep from spitting it all over his lap. Then the eternal pounding on screen gives way to two women stretched out on the bed. They touch and kiss in a way that makes you wonder what your friend’s nipples look like, what she would taste like. But you say nothing and tell yourself you’re just drunk and do another tequila shot to block out the thought of her perfect mouth.

You are twenty and hopelessly undone by the brave, bold sorority sister from Texas who walks around the house naked and asks if her pubic hair needs trimming. When she slips her hand under your skirt and asks if she can touch you, you simply nod and later try to reconcile your shame with the sheer force of your orgasm. Neither of you speaks of it again. Ever. When she goes home, you bury your grief in the arms of a man who buys you a diamond. You have a bridal shower, register for china, walk down the aisle in a white dress — and scold yourself again and again when nothing seems to be enough.

You work hard at being happy. This is the dream, you tell yourself, and after a while you start to believe it, until you are twenty-seven and you lock eyes with a brunette at a party. The attraction is instantaneous and unbidden. You tell yourself, Just this once, but you fall in love with her all the same and break your good husband’s heart. Later, when you don’t have the courage to see the affair through, you beg his forgiveness and do whatever you can to put your shattered life back together.

You learn to live with yourself again, even though you are different now. You and your husband laugh, love, fuck, fight, have a baby — all the ingredients of the life you were taught to want. And it works, until you are thirty-three and the white picket stakes you hide behind seem more like weapons than protection. So you pray, offer up promises, anything to stop thinking of that girl at work with the long brown hair and cinnamon eyes.

When you fail, you consider a compromise: a little fun on the side. When the fun turns serious, you get scared and tell her you will never leave your husband. You tell yourself that sex with her is not the best sex you’ve ever had, that she is a temporary fling. You grapple with your head and ignore your heart until your body turns against you: you no longer moisten at his touch, and your hair starts to fall out, and your stomach is in knots. You cry out for mercy and begin to face the woman you’ve spent a lifetime denying: you. All these years she has been waiting for you to acknowledge her. All these years she’s been waiting for you to tell the truth.

Caridad McCormick

Miami, Florida

I have pretended to be someone I am not for so long that I don’t even know who I am.

As a child, I pretended that my father wasn’t an alcoholic and a prescription-drug addict, and that I didn’t hear my mother crying in the darkened living room. In high school, I pretended to be a nihilistic punk rocker, with pink hair and safety pins in my ears. I was terrified of most of my boyfriends, but you’d never have known it.

When I became an adult, I pretended to be a paragon of corporate America, groomed and educated. It was this guise that attracted my husband, a conservative New Englander more than ten years my senior. He has no idea how many times I have been married. (I am too young to have the history that I do, and would still be too young at twice my age.) Appearances are extremely important to my husband, and he would never accept anything less than who I pretend to be.

I bore his child, though I have never been the mothering type. In fact, I made two appointments for an abortion but canceled them both at the last minute. My son, who just turned three, is a joy I never could have predicted, an uninhibited, gloriously wiseass kid. In a way, we are both experiencing childhood for the first time.

Day after day, I go to work in my boring business clothes. I love my profession but despise the company that I work for. I am who I need to be in order to earn the paycheck that the real me could never command.

Last year, I fell in lust with a programmer at work. We do the strange dance of attraction around each other. In another life, we might have been two beatniks speeding down Route 66 in a convertible, theorizing about the meaning of life. He is married and, like me, would never leave his spouse for fear of losing his kids.

It started when we innocently went to lunch one day — to bitch about work, as we often do — and on the way back to the car, he grabbed me, swung me around, and kissed me in the rain. To my surprise, I kissed back. My facade burned to the ground.

We have never consummated our relationship (if you can call it that). Oddly, this does not bother me. I find that I can tell this man anything: my pain, my desires, my fantasies. I have never had such a truthful connection with another human being, and I value this over sex, food, and all other basic needs. He does not judge me for my opinions and emotions; he encourages me to unleash them. In this life of lies that I have created, this affair is the most honest relationship I have.

Name Withheld

Thirteen-year-olds rarely get mail, so I was excited when the postman delivered an envelope addressed to me. My elation quickly turned to anguish. Inside was an obviously phony love letter over the name of a boy I had a crush on. I pictured the group of girls who taunted me at school laughing as they composed it.

That summer I attended sleep-away camp for the first time. No one there would know me, and I dreamed of being popular for a few short months. On the long bus ride to camp, I sat next to a girl named Rachel, who was to be one of my bunkmates. When we arrived at our cabin, though, we learned that eight of the other ten girls had been friends for years. We felt lonely and left out.

I didn’t give up on my dream of popularity so easily, however. In an attempt to win friends, I offered to do favors for the popular girls. The more I fawned and ingratiated myself, the more they included me. I had found a way to belong.

Meanwhile Rachel became the target of the popular girls’ teasing and pranks. Though I didn’t join in, I also made no attempt to comfort her or seek out her company.

Rachel liked a camper named David. One afternoon, when she was in the infirmary, someone came up with the idea of writing her a phony love letter from David. I slumped down farther on my bed and continued writing to my mom. I wish I’d had the courage to tell them how horrible their plan was, but I was too afraid of spending the rest of the summer as their new object of ridicule.

As the other girls chattered excitedly about what to say in the note, I noticed one of them walking toward me. I feared that she somehow knew about my prior humiliation and was going to expose me. Instead, she sat down on my bed, picked up my pink, heart-shaped stationery, and announced that she had found the perfect paper on which to compose the “love letter.” She was already walking away with the pad when she asked if she could use it.

I silently nodded my consent.

Stacey Cohen

Staten Island, New York

I lied to my mother about how long I’d practiced the piano, figuring I’d make up for it before my lesson on Saturday. It was a little white lie, like when she served us liver and told us it was steak.

My father lied when he said the spankings hurt him more than they did us. When he got cancer, his doctors lied to him about his prognosis, and my mother played along.

After my father died, my mother remarried. She lied to us about how happy she was, then went to the neighbors’ house to cry.

In the evening, on TV, we saw Southern senators filibuster the civil-rights bill in the name of states’ rights. We heard tobacco executives deny that cigarettes cause cancer. We watched as David Brinkley reported the Pentagon’s lies about the body counts in Vietnam. Then we listened to the president lie about why we were there.

We all wanted desperately to be deceived.

John Z.

Portola Valley, California

At the hairdresser’s, I eyed myself in the mirror. “Is my hair really that gray?” I asked Sherrie.

From a counter cluttered with brushes and curlers, Sherrie fished out a card of color samples. “This,” she said, tapping a swatch labeled Auburn No. 207, “is the color your hair used to be. I can make it that color again.”

“Do it,” I said.

At first no one noticed. Then one day I was eating lunch with Kelly, my friend and co-worker at the district attorney’s office. He stopped midsentence and narrowed his eyes at me. “Did you do something to your hair?”

“Can you tell?”

“Looks good,” he said, and picked up the conversation right where he’d left off.

Every six weeks, I breezed into the salon to maintain the deception. Sherrie applied the color solution, pale purple and unpleasant-smelling. For thirty minutes I sat on a black vinyl chair wearing a clear plastic bonnet and paging through Glamour and Cosmopolitan. Then Sherrie rinsed, combed, and cut my hair. Voilá, I was a redhead again, right down to my roots.

Over the years that Kelly and I worked side by side, my hair color changed from rich auburn to coppery red to strawberry and back. But Kelly never commented on my hair again.

Once, Sherrie tried a new color solution. It was a disaster. I called Kelly at the office. “My hair is purple,” I told him. “Cover for me.” Sherrie spent the rest of the morning laboring to get my hair back to a more normal shade of red.

Then one day Kelly called me at work from a hospital room. “The news isn’t good,” he said. After Kelly’s diagnosis came chemotherapy. He started to lose his hair.

Every morning before work, I’d brush my shiny red hair and hustle off to the office, where I would find Kelly looking thinner and paler, his hair wispier and wispier.

Kelly died in April 1997.

I let my hair go white.

Judith Phelan

Portland, Oregon