I. The First Six Days: Getting Used To The Heat

I make two stopovers on the way from San Francisco to Tel Aviv. Between Detroit and Amsterdam, I am seated next to a beautiful Indian woman named Sumitra. She asks why I’m going to the Middle East, and I say because I’m bored. I ask why she’s going to Romania, and she says for a wedding, which, I have to admit, is a better reason.

Inside the high-security area for the Israel flight, a beefy guy with thick black hair and bad skin asks me if I’m Jewish. I nod cautiously, and he indicates his approval. Then he tells me he’s a prophet.

“A biblical prophet?” I ask.

“A big one,” he replies.

Great, I think. I’m not even there yet, and already I’m meeting crazy religious people.

I was never a good Jew. When I was fourteen, I was locked up in a juvenile detention center where the juveniles were not allowed to smoke, but the adults were. Once a week I would go to synagogue in a room at the back of the compound and listen to the rabbi for a little while, because afterward we could eat and smoke as much as we wanted.

I was transferred from that center into a violent group home on the South Side of Chicago, but later I was moved to a better home run by the Jewish Children’s Bureau. The move was the rabbi’s doing, and it would not be unrealistic to say that if I hadn’t been placed in this more forgiving home, I would not be around today.

I haven’t spoken to the rabbi since.

Arriving in Jerusalem, I check into the Tabasco Youth Hostel in the Muslim Quarter. The Old City pulls my breath: the arches and the doorways. The foot-long, oddly shaped rocks pasted together with cement. Hundreds of Jews in black coats knocking the brims of their hats against the Western Wall, lit by arc lights. The Arab kids who grab my elbow, ask where I’m going, then run away. The tunnels and the cobbled streets and the apartments with no windows or roofs.

My first night, I am awakened at two in the morning by either a bomb or a gunshot; I can’t tell which. Then at 4 A.M. the Jews start singing their sad song down at the Wailing Wall, followed by the bells from al-Aqsa Mosque at 4:45: the sounds of two great monotheistic religions disturbing a good night’s rest.

While the priests clack along to the Ethiopian Monastery of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Old City glows with religious intensity, and I decide that religion is not all evil and stupid, as I always thought, but rather a reflection of both our best and our worst sides: an excuse for both abstinence and rape, war and peace, nationalism and homeless shelters, missionaries and the missionary position. All of it is tied up here, behind the white stone walls of Old Jerusalem.

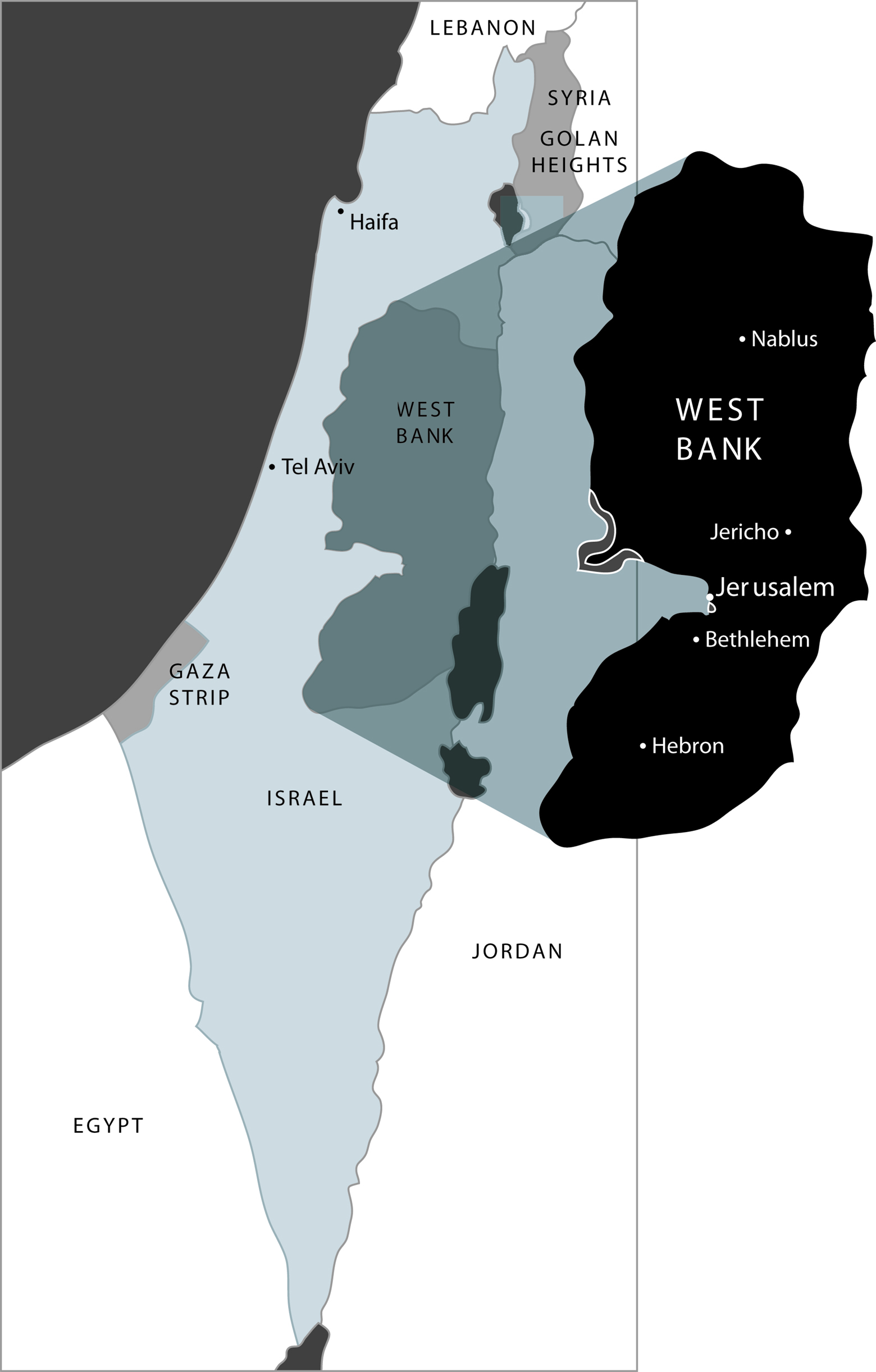

On my fourth day here, eight Palestinians are killed in Nablus by an Israeli helicopter. The Muslim Quarter is quiet. The stores have closed early and are not expected to open tomorrow. The owner of the hostel sits in the poolroom watching Yasser Arafat on Arab television. He tells me Arafat is demanding international oversight. The chief of police has declared Jerusalem the new hotbed for Palestinian terrorism, citing the stoning of some Orthodox Jews last Sunday. They were attempting to place the cornerstone of the new Jewish Temple atop Haram ash-Sharif, the third-holiest place in Islam, where Mohammed rose to heaven — if you believe in that sort of stuff.

I meet Janos, a German backpacker, at the youth hostel. We decide tomorrow to visit Hebron, where five hundred Jewish settlers (religious fanatics) are protected by two thousand Israeli soldiers, surrounded by 120,000 Arabs. Then it’s off to Gaza for two days. Seventy-two hours of chaos altogether. What should we do in the meantime? “Well, I’m German,” Janos says, “so I have to go to the Holocaust Memorial.”

The memorial is depressing and real. We tour the children’s museum — a shrine to the 1.5 million children killed in the Holocaust — then the Warsaw Ghetto exhibit: the maps, the stories, the pictures. After the war, in 1946, the Poles slaughtered fifty more Jews in a small town. Fifty out of two hundred, which before the war had been twenty thousand.

“We did this,” Janos says and draws his fingers across his forehead. He asks if I think he would have been a Nazi. I say, “Sure. You’re athletic and blond. You’d have done well for yourself.”

II. Dreaming Of Hebron

A long time ago, Abraham made a covenant with God in Hebron, but God has not been kind to this place since. The temple in Hebron is one of the holiest sites in both Judaism and Islam, and for a long time, Jews and Muslims worshiped there together. Then, in 1929, some Arabs brutally massacred more than a thousand Jewish men, women, and children.

Now the city is divided. Janos and I arrive in H1, Palestinian-controlled Hebron, at about noon. The streets are choked with traffic. The market is in full swing. Vendors line the sidewalk, selling fruit juice and shawarma and flaky pastries smothered in honey. Shoppers crowd the pavement until it feels the place will burst. And this isn’t even downtown.

We wait under the shade of a pharmacy sign for Rick from the Christian Peacemaking Team (CPT) to arrive. A Palestinian police officer stops to question us. While we’re showing him our passports, a passerby tugs at our arms; he wants to show us something. “They shoot at us from up there,” he says. I look where he is pointing and see the barbed wire and the bleached white building. “The military or the settlers?” I ask. “What is the difference?” he responds. There are bullet holes everywhere.

Rick arrives, and we follow him through the market to a street where the crowd thins. That’s when we hear the pop-pop of gunfire. We step into the middle of the empty street and cautiously approach an Israeli guard post on the border with H2, Israeli-controlled Hebron. The soldiers raise their guns tentatively. Rick asks what they are firing at, but they ignore him. They don’t like the CPT; the CPT asks dumb questions. “Who are you?” one of the soldiers says to Rick with a sneer. “You are nobody.”

Then the rocks come, big ones. The soldiers step forward with their guns aimed. I hide around the corner. Janos takes pictures. Rick protests that they are only rocks. But these are not pebbles; they are round bars of cement. “We’d better go,” Rick says to us. “They’re throwing rocks because we’re here. They see the camera.” Rick is one of those good Christian types who believes in the power of love. He thinks if he talks nicely to everybody, then everything will be OK. But I don’t believe in the power of love. I don’t believe in good guys.

Once we get past the soldiers, we are in H2, Hebron’s real downtown. But the streets here are empty and quiet except for occasional gunfire from behind us and the sounds of children from within the buildings. The stores are all closed. Nobody is out. The walls have been spray-painted with Jewish stars and slogans: No Arabs, No Problem; Arabs Get Out. Sometimes I catch a glimpse of a face between the bars in a window. This is the ninth day of round-the-clock curfew for all Palestinians in H2. They are not allowed outside — at all. The curfew is supposed to be lifted today.

I ask Rick how many people are under lockdown in these houses. He says forty thousand. Knowing his bias, I cut that number in half and figure there are at least twenty thousand people who have not been allowed outside in nine days. Prior to that, there were six days without curfew, and before that, eleven days with curfew. This particular curfew went into effect after a fight in the market between a Jewish settler and a Palestinian. There were no guns; nobody was killed. “The settler probably started it,” Rick says. I don’t think it matters who started it.

There are two thousand Israeli soldiers in H2: standing guard in watchtowers, at intersections, behind cracks in the walls. The five hundred Jewish settlers walk around freely.

Of all the settlements in Israel, this is the only one in the middle of a town. The settlers here are the most extreme Jewish militants, many of them members of the outlawed Kach Party, whose leader has been quoted as saying, “The only good Arab is a dead one.” The stated goal of the Kach Party is the removal of all Arabs from Palestine, by any means. The Kach Party has been outlawed since 1994, when one of its members, Baruch Goldstein, walked into Ibrahimi Mosque and opened fire on the occupants as they prayed. Twenty-nine were killed, and many others wounded. In nearby Kiryat Arba stands a shrine to Goldstein, who is considered a hero there.

Outside the four-building settlement, I talk to Karen, an Israeli guard. She was grazed by sniper fire a week ago and has a thick red scar along her neck. We stand in front of a devastated market surrounded by thick coils of barbed wire. Karen says the two groups — settlers and Palestinians — will stay here until one of them is gone. She says once upon a time, one side hit the other, and the other hit back, and they have been fighting ever since. She says the soldiers do not interact with the settlers, because sometimes they must face them, too. The settlers are crazy, she says. She just follows orders.

Entering the settlement, Janos and I try to speak with people on the street, but they ignore us. Rick told us the settlers would attack us, especially the women. The men carry large automatic weapons. I can feel my heartbeat in my throat. Then Janos pulls out a red napkin and does a magic trick for some children. Their mother wants to know how he does it. More children come. He says it is magic. He performs the trick three times, and the children shout and laugh, and the mother gives us water, because children everywhere love magic, and mothers everywhere love to see their children happy.

Above the settlement hangs a large sign: This is a Jewish market stolen by the Arabs in the massacre of 1929. Across from it is a tent the settlers have set up to protest the government for prohibiting their expansion. The settlers do not like the government. They do not recognize Israel.

When the curfew is lifted, Janos and I sit near the edge of the settlement and watch a slow trickle of Palestinians emerge and walk past the bus stop. We are joined by S., a photographer for the Washington Post, who has been covering Hebron for six weeks now. At the bus stop are six Jewish children. At first, the children taunt the Arabs, mocking them, holding their noses to protest the stench, walking behind them imitating monkeys. I ask S. what would happen if an Arab hit one of the children, and he says the Arab would go to jail for a long time. Soon the children grow bored and start throwing stones at the Arabs. One of the stones hits an old man walking with a cane; he doesn’t even turn to look at the children. Then they throw rocks at two Arab women.

Janos looks pained. “I just want to do something,” he says.

“Can you imagine the rage,” S. asks, “the humiliation of being taunted by children?”

I wouldn’t believe it if I weren’t here to see it myself.

The children are finally quieted by one of their elders, who doesn’t want the bad publicity. But where do young children learn these things?

“It’s too late for your magic trick,” I tell Janos.

III. When The Bomb Goes Off

I ’m in downtown Jerusalem when a bomb goes off, the worst incident since the June 1 bombing of a disco in Tel Aviv. Within twenty minutes, the streets are blocked off, and helicopters fly overhead.

It was a suicide bomber again, this time at the Sbarro’s franchise on Jaffa and King George. I rush to the scene. A worker still wearing his Sbarro’s smock walks back and forth on the perimeter in shock. I take out my notebook, and people immediately approach me to say, “You see what they do to us? And the world is angry when we kill them first.” Holding on to the sleeve of a reporter from the London Standard, I manage to get inside the cordoned area. Nobody cares if your journalism credentials are phony once you’re inside the police lines.

At first, there is concern about a second bomb, but it turns out to be an exploded tire. The restaurant itself is just a blood-stained skeleton. Forty reporters, not counting myself, jockey for position to interview Israeli minister of security Uzi Landau, who speaks firmly and with resolution, his smart white shirt shining in the afternoon sun.

The victims have all been taken to hospitals. The last count was thirteen dead, including six babies, and eighty wounded, but it’s early; those numbers are low. It’s been four hours, and they’re still picking up the glass.

I was on my way to buy a bus ticket when the bomb exploded. I was going to get out of Jerusalem for a few days, lie on a beach somewhere.

Landau says the Palestinian Authority has already declared war. There is no difference between Fatah and Islamic Jihad and Hamas, he says: “If they hoped to find a society of people that are going to give in, they are mistaken.”

I turn to the shell of the building, looking for clues to help me understand the situation. It was a big bomb, that’s for sure. Even the cement around the foundation is cracked and broken. The windows are completely gone, the steel bars twisted, the floor and the ceiling destroyed. But the metal cooking grills in the back seem undamaged. I move away to get a wider perspective. Two hundred feet from the building, a journalist tells me to watch out: I’m wearing sandals, and there are big pieces of broken glass in the street.

At four and a half hours, the numbers are eighteen dead — four babies, two children — and ninety wounded. Islamic Jihad is claiming responsibility for the attack, which was committed by a twenty-three-year-old man from Jenin.

One store inside the cordoned area is still open, and I buy a lemon soda. The reporter from Newsweek and the photographer for Time are speculating on Israel’s retaliation. “It’s going to be massive,” one of them says to me. “Go to Gaza this weekend if you want to get a story. That’s where the action will be.” We all laugh. A latecomer from a Swedish paper asks about the body count, and we rattle off numbers. It feels as if somebody is about to make a bet:

“I’ve got a hundred dollars on six missiles in Nablus.”

“I’ll take it, plus two-to-one on a curfew in Hebron and four police stations hit on the Strip.”

After a while, there’s only so much information to be found at the scene. The usual gaggle of bloodthirsty demonstrators stand outside the police lines howling for Arab blood. A tourist from Toronto tells me he was a hundred feet away during the explosion and saw a body fly out the window in a haze of smoke. He’s hoping to sell the pictures he took. All of the major news sources will print the numbers — there’s no other way to measure the loss — followed by some standard information about the length of the conflict. Already the mayor is taking phone calls from the New York Times and saying that the Israeli people are not afraid and will act as one.

It’s all drowned out by crying mothers and hawks bellowing for revenge.

I don’t find out until the next day that Janos was one of the injured. He was on the street right outside Sbarro’s when the bomb went off. When he gets out of the hospital, he wants to talk to me, to find out if I was with him. He can’t remember anything that happened in the last twenty-four hours. He also can’t hear, so I respond by writing notes. He had stopped to buy a battery for his camera. Now, holding the battery in his fingers, he starts to cry. We trace his steps from the store toward the bus station. He must have been heading for Tiberias. He can’t remember. On the way, he passed Sbarro’s, and the bomb went off. Today he woke up in the hospital.

Janos’s face is drawn and shocked. He’s the closest friend I have made here. I try to put my arm around his shoulder, but he says he just has something in his eye and that it is better to be strong. I write that he doesn’t have to be strong with me; I don’t know any of his friends.

Janos is hungry, so we go for pizza. Then he wants to see a doctor in Tel Aviv. His mother is worried about him. His hand shakes as he sips from a can of Coke. He says that in 1936, if you were a Jew and bombed a German restaurant, then you’d be a hero. This is how he explains it to himself. Janos is sensitive; he tries to like everybody; he feels guilty for war crimes committed thirty years before he was born. A bomb meant for somebody else almost took his life, but that’s what war is all about: the death of innocents. Janos says I can write about him if I want, but to make it clear that he doesn’t have anything against the Jews. It would kill him if anybody thought that. He’s ready to leave Israel now, he says. Here, it is madness.

In response to the bomb that took Janos’s hearing, the Israeli government takes over the Palestinian Authority offices in East Jerusalem and raises an Israeli flag on the roof. The Oslo Peace Accord is dead. A Palestinian police station in Ramallah is also leveled in retaliation, but no injuries are reported. East Jerusalem becomes a flash point. Arafat arrests terrorist cells in a bid for Western approval, but there is no bargaining here. There is no Palestinian government. The Palestine Liberation Organization is a relic, a stone without a voice. Islamic Jihad is nothing more than an underground tunnel from Nablus to Jerusalem. Hamas is the kind of anger you feel when nothing matters anymore and you have nothing left to lose. Israel negotiates with itself, because only Israel has power and guns and borders; you can’t negotiate with the wind. Israel makes all the decisions, including how many bombs it can live with a year. Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon bought a house in the Muslim Quarter with the explicit intent to provoke the Palestinians. A bedsheet-sized Israeli flag splattered with red paint hangs from the window. He doesn’t even live there. How many bombs can Israel live with? There will always be one, minimum. Start from there.

I decide to visit the flattened police station in Ramallah. The checkpoints slow traffic to a crawl, and by the time I arrive at what was once a police station, it is already dark. Overlooking a purple valley, the enormous building — as big as a high school — is now reduced to rubble and twisted metal bars. The Palestinian soldiers wave their guns at me in a way that suggests boredom. “American journalist!” I say several times, and several times they tell me to go away, that it is too late.

Finally, a major general decides to give me a tour. He points to the sky and stamps his foot when he speaks. When he makes a joke, everyone laughs. No one interrupts this man. “This is the main leadership of police,” he says through an interpreter speaking broken English. “It’s not army” — which is a technicality, because Palestine doesn’t have an army, just a very large police force. “It’s a savage state,” the general spits. “We have no chance to be human here. A child which is grown up will take our flag to the mosque in Jerusalem.”

I listen to the general talk for half an hour. He’s no better than the Israeli minister of security and his bullshit about Fatah and Hamas and Islamic Jihad being the same thing. The general speaks at a speed of five lies per minute. The best lie among them is about the evacuation of the police station, which coincidentally took place just moments before the missile hit, thereby sparing the lives of four hundred people. They knew this building was targeted. It was evacuated, and then it was destroyed, and, along with it, another major piece of the Palestinian infrastructure.

As I’m walking away, the interpreter says to me, “Listen, I’m a painter. All my paintings were in there.” I almost tell him there were four babies in that restaurant, but what does he know about that? He never planted a bomb. He’s just another innocent trying to exist where existence is impossible.

I take a trip to northern Israel, to rest: Haifa, Tiberias, Kiryat Shmona. The Jews here are not like the Jews in Jerusalem. They are more secular, tank tops the norm. The Golan Mountains embrace Kiryat Shmona. Hippies hike along the roads; punk-rock kids with mohawks taunt old people at the bus station. It’s just like the real world.

None of this stops the bomb from going off in Haifa. I was going to walk the Golan Heights and visit a Druze village by the Lebanese border. I thought I would bicycle the Galilee and lie on the beach in Tiberias. Now I’ve been thrown back into unpleasant reality.

In Haifa, the terrorist showed the bomb to the waitress before detonating it. He lifted his shirt and said, “Do you know what this is?” A sexually charged gesture, for sure: Would you like to touch my bomb? But the waitress’s scream — followed by a thrown chair from the cafe owner — sent the people out into the street, and when the bomb exploded, there were twenty-two wounded instead of twenty-two dead. And the demonstrators lined the periphery, as always, screaming for Arab blood.

IV. Return To Hebron

I ’m back in Hebron with a photographer named Rachel. This morning, Imad Abu Sneineh, a senior Fatah member accused of shooting at settlers, was assassinated here by undercover Israeli forces. The stores are closed.

I hear a loud bang, and I turn the corner to see Palestinian children throwing stones at soldiers, then running toward me. It’s a game to them. I wait around the corner with the children. They run again, and I hear gunshots, the empty shell casings clattering on the streets. The children become bolder, and then there’s another loud boom, another bullet. This is not a game. One child jumps into the arms of five others, and they run off with him, screaming and laughing. He was shot, they tell me, in the leg. And then the same child returns, smiling. What fun.

Things are heating up. The taxis have all left. The adults have left. The adults are not immortal, only the children. The children throw a flaming bottle, then another. A couple of rocks come my way. Rachel and I edge closer. This is not fun. This is not a game. Gunfire, flaming bottles, rocks. These kids don’t want their pictures taken. Rocks clatter toward our feet. Secretly, these children do want their pictures taken. They want orange popsicles. They want to be superheroes.

I sneak inside an open store, buy a bottle of water, and step back outside. Bang. “Rachel, what are we doing here?” A car window melts. Horns, stun grenades. Then the bullets start coming not from the military posts, but from up the hill. Settlers? “Rachel, where are you going?”

The children do us the favor of not throwing rocks and flaming bottles while Rachel and I, hands to the sky, cross the line between H1 and H2.

There are three photographers on the other side. The soldier nods to me. He’s the same one I talked to last time. I recognize the funny hat he wears to keep the sun off his neck. He says those are just children; the adults are all at the funeral of the assassinated Fatah member. Wait, he says; give it time.

I follow the soldiers as they retreat and set up a new position. I am five feet from the soldier when the rocks fly again, and he raises his gun and fires a single shot, chest high. There is no one there. The rocks come in at angles, never from straight ahead. I feel safer on this side of the line, behind the guns.

My ears are ringing, and I stuff them with Kleenex. I change positions and see the children leaving their hiding places, entering no man’s land. They are coming closer, and the soldiers are firing more and more often. Any minute, someone is going to be hurt.

More photographers show up. The journalists outnumber the soldiers, but there are more children than all of us put together. This is more than a perceived threat. Five hundred settlers. Two thousand soldiers. One hundred twenty thousand Palestinians. Those five hundred settlers are the only reason we’re here. No settlers, no military; no military, no journalists; go back home, get a real job, raise a family.

All of this shooting is giving me a twitch.

Five small fires burn among the soldiers in the street. I set off with two photographers for the funeral. The children escort us through H1. The streets are empty.

At 4 P.M. the Palestinian flags are waving at Hussein Mosque in H1. All the men from town are here. The journalists, too, a dozen or more. The Associated Press has an armored truck. The journalists are mostly photographers. The reporters will fill in the blanks from New York, Milan, Paris.

The ambulances arrive, men with guns. A sad song plays from the speakers atop the mosque. A soccer field full of mourners for Imad Abu Sneineh. Guns swing into the air, shell casings falling like rain. A thousand men bent in prayer, thousands more in the street. A body wrapped in a Palestinian flag.

In the streets, Hamas rules. Teenagers grab the journalists and threaten them, but the older men smack the boys on their heads. The men want the journalists here, as witnesses. The funeral procession starts. A circle of men forms around the dead body, shouting and jumping, arm in arm, pulled along with the tide of the procession. How many mourners? Five thousand? Shouts for revenge. As the funeral moves, it grows. Cars and ambulances join it, and Palestinian guards with their red caps. The crowd goes on forever.

After an hour, I can’t stand any more gunfire. My ears are ringing, my nerves shot. I return to H2. The border is now heavily guarded. What happens when the funeral is over? That is the question.

The Christian Peacemaking Team invite me to have dinner with them: meat stew with string beans and instant tea. They ask me if I would like to join them in prayer. I say no, I’ll be in the other room. I’ve seen three groups pray today. Only the Christians prayed without guns. They are good people. I give them a twenty-shekel donation for the home-cooked meal.

When the funeral is over, nothing happens. As the sun goes down, I board a late bus for Jerusalem. A man from the settlement approaches me. “Show me in the history book,” he says, “where there is a Palestine? There is no Palestine; it doesn’t exist. Anyway, it doesn’t matter, because the Bible says we will win.”

“You’re right,” I agree, “it doesn’t matter; you just keep hold of that book.”

He accuses me of being on the Arabs’ side. I tell him that’s ridiculous; I’m Jewish. He says next time I will come to his house for a glass of wine. Here in the land of Abraham, the doors are always open.

In the morning, the news media report an overnight attack by Palestinian forces in Hebron. Wait until the funeral is over.

V. On The Strip

I spend my first night in Gaza behind the safe blue wall of the United Nations Beach Club, surely the most exclusive club I have ever been in, open only to UN workers and journalists. I have drinks with diplomats while a tropical breeze blows in off the Mediterranean and a procession of Hamas children stop to tell me, “Arafat!” and then stomp their feet to grind the old guerrilla into the sand.

Gaza and the West Bank, though often grouped together, are not at all the same. The people do not even look the same. In Gaza, the Palestinians essentially have self-rule, but no control over their own borders. In Gaza, you don’t have to worry about being mistaken for Jewish; a Jew would never walk the street there.

Gaza is bustling, dense, cut off, and poor — funded by cracks in the coffers of Arab nations. Unemployment is at 60 percent, and the only career path is the Palestinian Authority police force. In Gaza City, four or five hotels stand empty at the end of the main drag. This was once supposed to be a vacation spot, but now the beaches are filled with rocks and trash.

Some people refer to Gaza as the largest jail in the world. It is twenty-eight miles long, five miles wide, and surrounded by an electric fence. Israel controls all borders, including the sea. Since the start of the Intifada — the Palestinian uprising — the Arab population has not been allowed in or out. The water is poisoned with salt and nitrates, and many infants die from “blue-baby syndrome.” The last fifty years here is a story of abuse and tragedy. From 1948 to 1967, Gaza was part of Egypt, but the Gazans were never given Egyptian citizenship, and the refugees who fled here to escape the war between Israel and its Arab neighbors were never offered permanent homes. Rather, they have been unfortunate pawns in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Mortars are fired today at the border crossing in Rafah, between Egypt and the Gaza Strip. I go there and speak with Mahmoud, who lives in a tent atop a pile of rubble that was once his toy store. In the ruins, I can see the heads of dolls and pieces of his computer and cash register. “This is my home,” he says, pointing to the rock-strewn field, “my library,” waving a hand at the air. He arrived, he tells me, on August 11 of last year, just before the latest intifada. He’s Egyptian and wanted to be close to the border so he could go back and forth and visit his family. He says this was not an area of heavy shooting, but on the morning of May 2, the Israelis came with bulldozers, and he had to flee his house in his pajamas. This is what he has left. Mahmoud hands me a card with silver edges. It says, “Mahmoud Hassan el-Shair, export-import,” and gives numbers in Cairo, Gaza, and Rafah. He speaks perfect English, this man who lives in a tent.

Half of Gaza, more than six hundred thousand people, lives in refugee camps, creating a two-tiered society. The Gazans whose families were here before the war in 1948 look down on the refugees who arrived after the war. But the natives are also jealous, because although the refugees have less room and poorer services, they have better schools, run by the UN. I walk through the narrow, unpaved streets in the refugee camps, followed always by a crowd of children. The adults keep inviting me into their houses. Finally, I go inside. A child is sent for tea and comes back with a two-liter bottle of soda. Men lie on mats on the floor. What does one do in a refugee camp? Sit. Talk. Wait for the UN to hand out packets of food. Pray.

The Palestinian Authority is not strong here. Arafat can hold his own in Gaza City, but not in the other two population centers, Rafah and Khan Younis, which are strongholds for the Hamas movement. There are also smaller, grass-roots rebel cells that aren’t affiliated with Hamas or the Palestinian Authority, but are responsible for many of the mortar shells lobbed into Gush Katif, the large Jewish settlement on the southwestern end of the Strip. Things have not gotten better in Gaza since the Oslo Peace Accord, but rather much worse. Several people tell me they were happier when Gaza was an occupied state.

Last Wednesday, a mortar was fired from Khan Younis into a Jewish settlement. The shell hit a schoolhouse while class was in session. The Palestinians were not targeting the schoolhouse; the Palestinians don’t have that kind of aim. It was an unlucky shot. In response, Israel pushed back the border another hundred meters. The UN, as usual, set up tents over the destroyed buildings: large green sacks with blue water coolers.

I walk from this area to an Israeli checkpoint. It is very rare for anyone other than a handful of Arab workers to try to come through this way. I stand under the netting with Michael, an Israeli soldier and American immigrant, while they run my documents. After an hour, Michael offers me some cake. In the U.S., Michael was not accepted to his first-choice college and thought his chances would be better after some life experience in the Israeli military. He says the Palestinians shelled the school, so Israel had to take drastic action. He says a civilian with a gun is no longer a civilian. He says soldiers hide out in civilian houses, so Israel has to destroy their homes. He says it’s tragic, but they can’t afford to let Israeli citizens be bombed. He says you can’t beat the Palestinians, because they don’t mind being killed. “Nothing makes sense here in Gaza. How do you reason with suicide bombers? Smear pigs’ blood on the mosques; put alcohol in their water. That will get them to stop.”

Tonight I am staying at a youth hostel in Gush Katif. I am the only one here. Down the road is a four-star beach-front hotel: closed. The tourist industry is not doing well.

The streets are clean. It’s a balmy night, and the settlers are out walking around. Eight thousand people live here. Most work in agriculture. Gush Katif is self-sufficient and exports $50 million in organic vegetables every year. The standard of living is as high as anywhere in Europe.

I go to the Yamit Yeshiva, the religious school that boys attend before and after their stint in the military. The school is built in the shape of the Star of David. Students from all over Israel come here to study. A friendly kid named Alon shows me the monument to Kal Yamit, built from broken glass and stones. Kal Yamit was a settlement in Sinai that was evacuated when Israel made peace with Egypt in 1989. Many of the settlers here are from Kal Yamit, and the yeshiva takes its name from their former home. The monument reads, “If you remember, you can build it again.”

Alon shows me where a bomb hit last Sunday. Parents were visiting with their children at the time. He introduces me to a group of shirtless eighteen-year-olds lounging on couches, smoking tobacco from a hookah. Alon says they hear shooting every night; you have to live with it. Last week, there were ten bombs. He shows me the crater and the walls pockmarked by shrapnel. On the second floor of the yeshiva is the Etaman Library, named after a student who was shot last year while driving from Kalim to Israel.

I’m struck by the peace of the settlement, even when I hear a bomb go off in the distance. A group of children sit on a tractor. The residents drive each other around; all you have to do is stand on a corner and wait for a ride. They have turned the desert green and built a beautiful village.

Menachim is a settler who lives in the hostel where I’m staying. At midnight, I go with him across the border to Egypt to buy a pack of cigarettes from some Palestinians who live in a shack in no man’s land. We have to cross two sets of razor wire to get there. Here I am, past the checkpoint, in a settler’s car, at night. This is how people get killed. I wait in the car, listening to the waves falling against the shore. Paradise. Then Menachim returns with his smokes, and we go back through the checkpoint. “No cigarettes, no sleep,” Menachim tells me in his limited English.

Back at Katif, I find out there was a military operation in Gaza today. An Apache helicopter attacked a caravan, killing militant Hamas member Eilal al-Ghoul. It’s two in the morning. At three, the soldiers return from their mission with dusty fatigues and messy hair. They say they were responding to mortar fire and shot at the perpetrators; they were not aware that one of the men in the car topped the Israeli most-wanted list. The men-boys go off to shower and get some sleep. Only hours after the attack, the Jewish media are already broadcasting the message from Hamas calling for infidel blood.

I spend the morning with Debbie, public-relations director for the settlements in Gaza. She’s showing me around the tip of Gush Katif when three mortar shells land on the small settlement of Kfar Darom, five minutes away. Debbie becomes agitated. She wants to show me the hot-house tomatoes and the cows, but they will have to wait. We’re going to Kfar Darom.

Fewer than three hundred people live in Kfar Darom. Like the settlement in Hebron, it is unsustainable in the long term: too small and surrounded by an angry Arab population.

A tank stands in the road between the two settlements and will not let us pass. Debbie makes a flurry of phone calls while we are stuck. There are three phones in the car, all ringing. Reporters are calling Debbie for the story while we sit on the pavement, unable to see anything. This is how the news gets reported.

Debbie gets word from the camp: a bomb fell on a house. The soldiers say there is also a shooter. An armored vehicle takes off into the field. As the shooting gets closer, we are herded behind the military base.

From behind a steel drum, I can see the shooting in an open field. I see a bullet kick up the red dust near the tank wheels. Then we are pushed out into the open. The soldiers are screaming. We sit with three ambulances, waiting for the outcome. Word from Kfar Darom is that no one was hurt.

Twenty minutes later, the roadblock is lifted, and we speed toward the settlement.

The mortar shell crashed through the roof of the single-family house, ripping a hole the size of three basketballs in the tiles, the cement, the paneling. The floor is covered in rocks and water from a busted pipe. The mother stands with her baby below the hole in the ceiling. The baby’s lips are covered in formula, and she plays absently with a spoon.

The TV crews arrive en masse. We step around the puddles in our sandals. The mother wipes the baby’s mouth. The father offers to run an electrical cord for the cameraman. Outside, shooting breaks out again — rat-tat-tat — but nobody seems much concerned.

Debbie tells me that all eight children were with a neighbor at the time, except for the baby. The mother and baby were five feet away on the other side of the wall, doing laundry. The father reads a prayer. Rat-tat-tat. Amen.

A resident tells me that only religious families live here. I ask if he lives close by. He says there are only fifty houses; everybody lives close by. I ask if they couldn’t move to the larger, more defensible settlement of Gush Katif. He tells me, “You give them Kfar Darom, and they will take Jerusalem.”

In the front of the house, I see the soldiers firing, and three rapid tank bursts. A little girl says, “The same thing happened to my house.”

The mother heard the first mortar shell land outside, then another. The third came through the roof. The army needs to hit the people who did this, she says: to “clean” them. She says the settlers here are not given the same protection as people in Tel Aviv or Haifa, a common complaint among residents of remote settlements.

The children will go away for a few days so the parents can clean up and fix the damage. Then the children will come back.

I ride with the children to Beersheba, where they stay and I catch a bus for Jerusalem. I’m done now. Buy some presents. Go to the museum. Head back to California.

On the bus to Jerusalem, I’m seated next to a soldier whose leg intrudes well into my space. He’s talking on his cellphone. Israelis love cellphones. They never turn their ringers off, and beeps and whistles sound every few minutes. I point to the soldier’s leg with my pinkie and tell him, “First I will take your leg; then I will take Jerusalem.”

On the plane, I miss Israel almost immediately. If you’re not an Arab or a Jew, then it is easy to make friends there. I sift through my notes, looking for a “through line” — a thread of plot to hold the story together. There is no through line here. There is no method to this madness. I sent some of my dispatches to an old mentor of mine in Chicago. He said bitterly that Arafat is like Mohammed, who, fourteen hundred years ago, made treaties only as a ruse to break them and conquer his enemies. Fourteen hundred years is a long time to hold on to resentment, and if it’s lasted that long, then it isn’t going away anytime soon.

Back home in San Francisco, I hear they’ve just passed a law against discrimination on the basis of a person’s weight. The news is filled with mergers and energy concerns. San Francisco has a black mayor. Last year he ran against a gay challenger. Race and sexuality never even entered into the campaign. I’m going through hate detox. I need a fix.

I think of lying awake at night, listening to hymns on the warm breeze of the Old City. I think of the suicide bomber in Haifa raising his shirt and saying to the waitress, “Do you know what this is?” I think of the injured pride of the men continually harassed and abused at checkpoints, and the unfathomable poverty of the Gaza Strip. I think of a land that elects its leaders out of anger, and another with no elected leaders at all. I also think of the thousands of people living on settlements for much of their lives, perhaps all of their lives. And I think of the busy markets of the Old City, the architecture, the museums and the mosques, where the priests and the rabbis and the sheiks and the alims walk the cobblestones in the early morning, before the workers or the merchants, long before the sunrise.