On a shelf in my home I have my brother’s record albums, their covers worn with handling, sticky residue evidence of his fondness for candy. Johnny Mathis, Frankie Lyman, the Drifters, Martha and the Vandellas: “Oh, Jimmy Mack, when are you coming back?” On the dull black vinyl of Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, a fingerprint offers itself up like a message from the past. As I slide the record back into its jacket, a photograph tumbles into my lap: my brother, perhaps twelve, eyes closed, pretend microphone in hand, body leaning into the music. I can hear his off-key voice trying to be like Smokey’s: “I’m on the outside looking in, and I don’t want to be.” Everything else in the picture is blurred, as though my brother were the only solid thing.

Everything of my brother’s fits on a couple of shelves: boxes of records, books, a few photographs. When you’re killed at eighteen, you don’t leave much behind.

In December 1968 I was recovering from the birth of my first child three months earlier. A hemorrhage during delivery had left me anemic, and the days had turned hallucinogenic, constructed of jagged shards of color. My brother had shipped out to Vietnam in October. My marriage was faltering. My mother was angry at me for not having married a Jew. My Cuban husband worked six twelve-hour days a week at Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, a leading military contractor. The rent on our Queens apartment would be raised in January. He wanted to buy a house in an isolated section of Long Island, but I’d always lived in the city and had never learned to drive.

Vietnam permeated everything that Christmas. Even the carols seemed part of the national deception: “Peace on earth, goodwill to men.”

My anger at my husband had deepened over his views on the war; his cavalier attitude about working for Grumman; his support for the president’s policies; his lack of support for me. I dragged myself through the gray-lit days in a stupor. We argued over Vietnam, my exhaustion, his late hours, the mutual hate between my mother and him, whether to have a Christmas tree or a menorah, to move or accept the rent increase. He said I was weak; his grandmother had had fourteen kids and after each birth had gone back to the fields to cut sugar cane. I paced, took iron pills, told him he was unfeeling. I snuck out of the apartment to smoke cigarettes. Finally we agreed to a temporary truce. We agreed to postpone the arguments until an easier time. We agreed to pretend.

It was just before dawn: The baby slept. My husband showered. I stared out the window at the Manhattan skyline ablaze with holiday lights, as if the city were on fire. A Christmas tree twinkled in front of our apartment complex. Dirty snow rimmed the streets, and pigeons rested on windowsills, casting ominous shadows against the panes. A chorus of salt-spattered cars backfired and honked below. The apartment air was oppressive, close. That sorrowful, pleading carol “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” played on the radio: “We’ll have to muddle through somehow.”

The phone rang. A man with a husky voice gave a name I don’t remember, confirmed who I was, then cleared his throat and recited by rote, “We regret to inform you . . .”

I remember little things: The coffee left brewing too long; its bitter, weary smell. Half-browned bread popped up in the toaster. How the streetlights flickered, then went out as the sun began to crack open the early-morning sky.

The man on the phone, who was calling from my mother’s home after having delivered the news to her in person, advised me to “come now,” as my mother screamed, “No! No! No!” in the background.

I hung up.

“My brother is dead!” I yelled into the recesses of the apartment. I drifted up from my seat, my body threatening to collapse. I was entering the baby’s room to wake him when my husband stepped out of the bathroom, encircled by mist, and said, “What? I couldn’t hear you.”

My mother came to stay with us as we waited for the body to be brought back to the U.S. She and I fed the baby, played with him, took him on long walks. My husband went to work. (“Staying home isn’t going to change anything.”) Friends dropped by with deli sandwiches, baskets of fruit, cookies, chocolate. We received official documents from the military: commendations, explanations, letters of sympathy signed by generals: “A barrage of gunshots . . . mourned by his fellow marines . . . bravery . . . Purple Heart.” In bed at night, I conjured a memory of my brother at my wedding: He’s standing beside my husband’s cousin, whom he has a crush on. His eyes are bright, and he’s slimmed down from the chubby child he once was. He says something that makes the cousin laugh, sees me watching him, and winks.

My brother and I had lived much of our lives apart. After having battled with my mother over a phone bill as a teen, he’d gone to live with his father, my stepfather, somewhere in Brooklyn. I didn’t know much about how he’d spent those years, but I kept reaching for the sparse memories I did have of him.

When my brother was twelve and I was eighteen, the police left a message that they’d arrested him for stealing a car. My mother wasn’t home from work yet, and I ran the eight blocks to the station. The squad room was overheated and stank of sweat and some unidentifiable food. I remember cells, doors leading to shadowy rooms, accused men proclaiming their innocence. The police wouldn’t let me see my brother. They stood over me menacingly and called me “street cunt.” I went outside and sat on the front steps to wait for my mother. The cops walking in and out glanced at me, nightsticks swinging against their legs, their holstered guns passing me at eye level. A couple of men on the other side of the street shoved each other and screamed in Spanish. Gulls wheeled overhead on the winds off the East River.

When my mother arrived, she straightened her shoulders, said, “Wait here,” and went inside.

My brother had been an unsuspecting passenger in the stolen car, but he was sent to a group home for a year anyway. I remember taking the train from Grand Central Station to Pleasantville, New York, to visit him, but I don’t remember the visits.

My memories of my brother are disconnected, without contiguous flow: he is two, he is six, he is ten, he is twelve, he is fifteen, he is dead.

When his body finally arrived from Vietnam, they told us it was too perforated with bullet holes to be shown to family members. We stood before the closed coffin at the funeral parlor as if before a holy icon, though the coffin itself was nothing special: standard military issue, as common as M16s. Four marines in crisp blue uniforms and shining brass guarded the body. The proper time to have guarded it, I thought, would have been while it still breathed. As we stared at the coffin, a fantasy seized me: my brother was still alive somewhere in Vietnam; the marines had lost track of him and fabricated this cover story. That Christmas it was easy to disbelieve the government.

I wore a leftover black maternity dress, belted at the waist, and felt unwashed and gritty despite the two showers I’d taken that day. My feet were freezing in tights, wool socks, and scuffed boots. My mother sat crumpled on a chair, a loose arrangement of bent limbs and bowed head. My stepfather, whom I hadn’t seen in years, greeted me by saying, “I’m still the handsomest man in Brooklyn, aren’t I?” We hugged, and any animosity over his divorce from my mother, after he’d gambled away the rent and food money, was forgiven. A death accomplishes that.

My husband, handsome in the suit he’d worn for our wedding, whispered to his aunts and cousins in the back of the room. The cousin my brother had been attracted to sat in the front row, weeping silent tears beside my mother. I felt as if I were in a foreign movie, something Greek or Italian where everyone wore black and spoke too fast for me to understand. I stared at the coffin and thought about how I’d once had no idea where the Mekong Delta was.

I accepted my share of blame. I’d complained about the war but hadn’t protested it. I had been too caught up in my marriage and finding temporary work (I’d been fired when my pregnancy had begun to show) and trying to push through the postpartum exhaustion. I hadn’t written letters, gone to demonstrations, participated in sit-ins. I’d done nothing to try to end this war.

The snow was falling heavily when we left for the cemetery, wind whipping up white ghosts. The body was loaded into a hearse with pale satin curtains in the windows and a stealthy engine. Our car skidded and slipped all the way to Long Island National Cemetery, where we stepped onto a plain of squat white stones that must have been churned out by the hundreds. There were fewer of us here than at the funeral parlor: my mother; my husband; a handful of friends, aunts, and cousins; the rabbi assigned by the funeral home. We advanced toward a hole in the ground covered by a black tarp. A couple of men in heavy clothing stood at a distance, shivering. One, in a black wool hat and army jacket, nodded in sympathy to me. My stepfather was already standing over the grave, a slight figure in a skullcap.

As the rabbi moved between the rows, he looked carefully at each name as though making a list. He turned to my mother and said, “Out of the question.”

Leaning on my husband’s cousin’s arm, she stepped around the rabbi the way you’d circle a rock or another nonsentient object in your path. The snow coated the rabbi’s black coat and hat as if intending to bury him also.

I waved my husband on and stopped to talk to the rabbi alone. “What are you saying?” I asked. The wind blew the words back into my face.

“There are non-Jews buried here,” he said. “How can I pray?” He asked this as though it were a reasonable question.

As I battled my desire to strike him, I thought of my husband’s accusation that I would always be a hoodlum from the streets, that anybody could see it. At that moment, I hoped he was right.

I put my face close to the rabbi’s, and he took an alarmed step backward. “You will pray here,” I whispered close to his cheek. “You will pray here because God — the real God, not the one you’ve made up — mourns every dead child. You will pray here, because otherwise I won’t let you leave.” I put my hand on his wrist and smiled at him. My lashes were coated with snow, and my scarf flapped around me like a black flag.

The yeshiva had not prepared the rabbi for this threatening woman who would bend him to her will. He glanced from side to side. Nobody was watching. We could have been alone in an alley. Finally he nodded and walked to the graveside. His dark beard caught the pristine snow. He leaned over the coffin and prayed in a low voice, his eyes fixed on the hole in the ground.

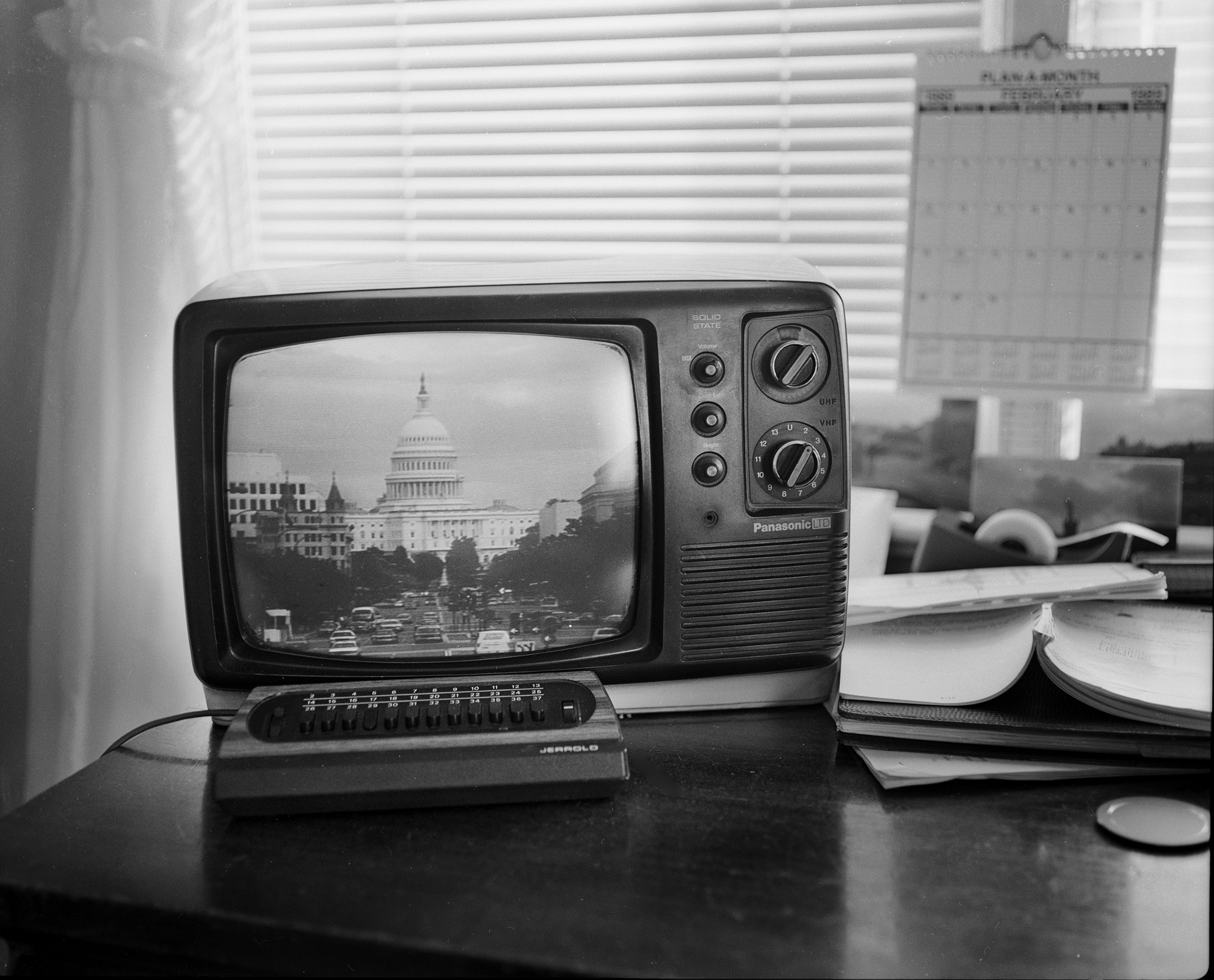

News of the war dominated the papers. Rows of coffins covered with American flags flashed across the television screen. Every night I dreamed my brother was alive, being tortured in a prison camp, running between dense green palms, crawling through rivers, panting, screaming, leaving a trail of blood that his enemies would follow. I’d wake covered with perspiration and gasping for breath. Some friends said I was projecting my own anxiety onto his death, others that I had a telepathic connection, a few that I was having a nervous breakdown.

I prayed that my gentle brother had died instantly rather than suffered pain. I remembered his pride when he’d received his very first paycheck and had “adopted” a Korean war orphan, faithfully paying fifteen dollars a month — until he’d lost his job and enlisted in an act of desperation, believing the military’s promise to provide an education. I thought of his certainty that someday he’d leave the city’s tenements behind and move to a farm and grow vegetables and flowers, a dream he’d picked up from a book we’d read together as children. I had marveled at his decision, during our poverty-stricken childhood, never to steal, whereas I’d had no problem shoplifting. I wept that my brother — sensitive, good-natured, astonished by cruelty — had been sent to Vietnam. I wanted to prevent the same from happening to any other boy.

I began attending antiwar marches every week, bringing the baby with me: bottles, blankets, diapers, toys. I didn’t believe that it would make a difference. I knew it wasn’t people protesting in the street that would end the war; it would be over only when it was no longer profitable. But I wanted that spirit of protest to seep into my son. I waved signs and chanted, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” This became my penance for my previous inertia. It would be five more years before the war ended, and several more after that before my nightmares would be gone and I’d accept that my brother was truly dead.

When the Bush administration decided to invade Iraq in 2003, I protested in Washington, D.C., with a friend and later in New York City with my second husband. Millions of us around the world demonstrated, but it didn’t stop the invasion. As I watched the bombs drop on Baghdad, I wondered if we are infected with some malevolent virus that will not let us value peace.

It was nearly Christmas that year when my friend Sarah called to tell me, in a hesitant voice, “Jamie is dead.”

The news was on in the background this time. No carols.

“They’re bringing his body back from Iraq. No announcement yet on the funeral.”

We hung up. What else was there to say?

I’d first met Jamie at a party Sarah had thrown for writers. His wife, Marika, was writing a novel about leaving Russia to seek freedom and opportunity in the U.S. They were newlyweds, both twenty-two, and had met in an English class. Kevin, my husband, spoke with Jamie about his decision to enlist in the National Guard for financial help with college tuition. Marika and I discussed her novel. She was concerned that Americans would be unable to relate to characters based on people she knew in Russia. “Americans seem to have little understanding about life in other countries,” she told me. She shook her head and took a sip of her wine. “But I’ve made such good friends here.”

A few weeks later I saw Jamie and Marika’s picture in the newspaper above a story about National Guard members shipping out to Iraq. There they were, arms around each other, Marika’s eyes full of love and dread, Jamie’s smile tentative. (I thought of all the times his mother must have told him to “smile for the camera.”) His arm was wound around his young wife, his military beret perched on his head.

He lasted one month in Iraq.

At the funeral Marika, weeping bitterly, said, “I thought this couldn’t happen. He was in the National Guard, not the army.”

Jamie’s flag-draped coffin was not pictured in the paper. It is forbidden now for returning coffins to be shown in the news.

I recently went to a concert by Anaïs Mitchell, who sang a song called “Tell Me Something,” about the invasion of Iraq: “Tell me something good about my country, tell me one good thing.”

I have no answer for her, but the lyric still haunts me. It makes me think of my brother, dead in Vietnam, and Jamie, who died thirty-five years later in a different war, which is really the same war. To those who die, they are all the same war.