I WAS ELEVEN AND MY BROTHER WAS SEVEN. For most of that summer of 1955 we’d roamed the Brooklyn streets while my mother worked for less than minimum wage, filing medical forms in the hot, dusty basement of an insurance company. Each night over dinner she quizzed us about our day. I didn’t tell her I’d stolen cookies and soda for my brother and me, nor that we’d disobeyed her explicit orders and gone to the pool in the park half a mile away, where junkies shared needles. I told her about going to the library or reading on the fire escape. She was too shrewd, though, not to suspect the truth. She hated where we lived, but what choice did we have, on her salary? Yet that summer she shocked us by somehow saving enough money to rent a bungalow for a week in Coney Island.

The rental was a tiny place, the kitchen so narrow there was room for only one person at a time. But the sound of the waves made that gray-shingled shack on the edge of the boardwalk as exotic to us as a Caribbean hideaway. At night the pungent smell of seaweed and the brassy music of the nearby merry-go-round floated in through the screen windows. My mother read on the beach every morning, her rich olive skin darkening to a burnished mahogany, a brown paper bag stocked with cigarettes, soda, candy, sandwiches, and extra books on the gritty sand beside her. My brother and I played at the edge of the water, dribbling wet sand through our fingers to build sand castles in the golden sunlight. We swam in the ocean for hours, emerging with blue lips and puckered skin, too excited even to eat lunch.

Evenings, the boardwalk was crowded with refugees from the hot city. Neon blazed, and loud music exploded from every arcade. The aroma of hot dogs, hamburgers, beer, and knishes mingled with the salt-scented breeze. It was the first time I’d known the expansive luxury of the open sky curving to the horizon.

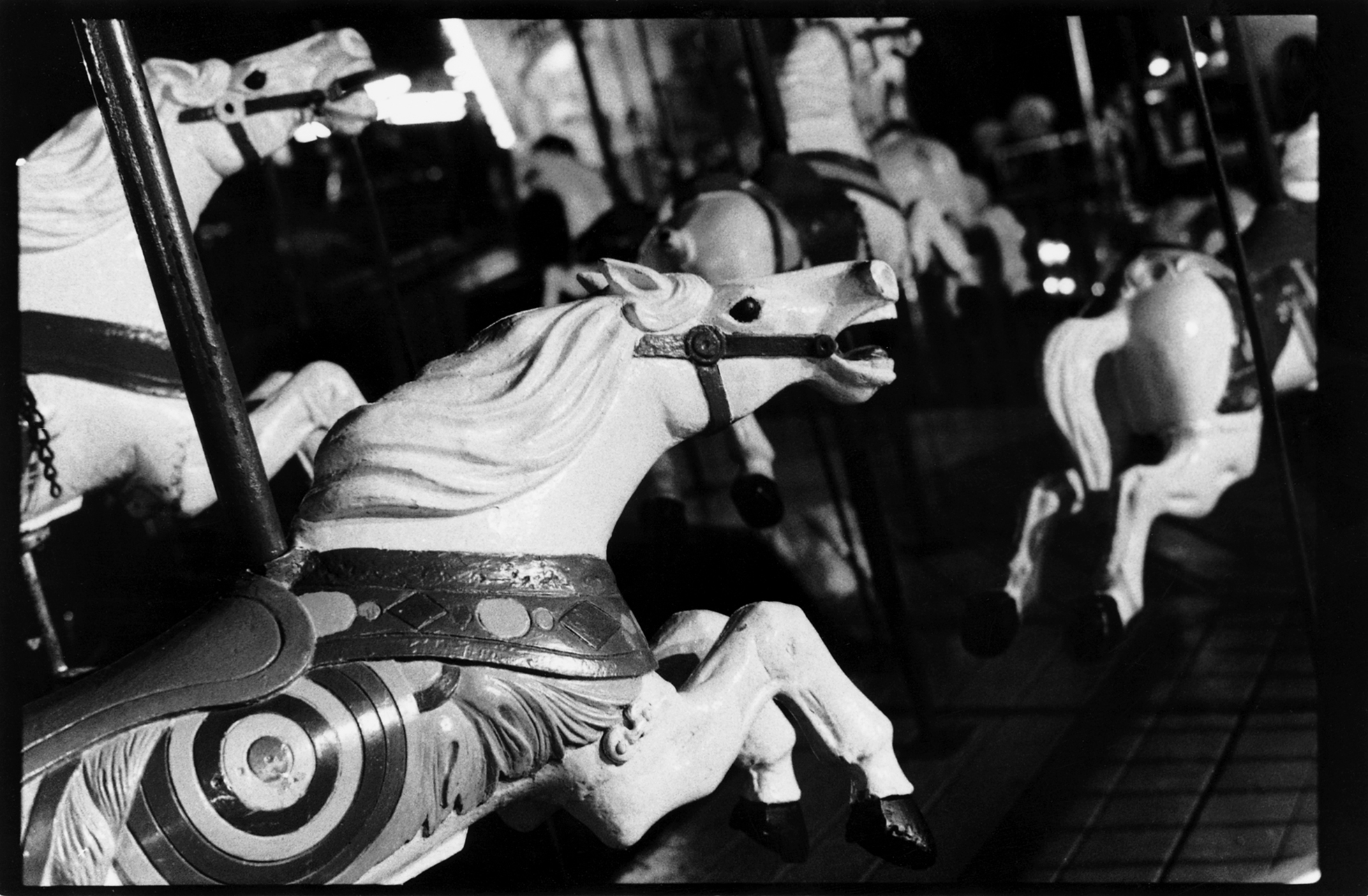

The biggest attraction on the boardwalk was Steeplechase Park’s Pavilion of Fun, an enclosed carnival of rides and games. Rising above it was the Steeplechase Park racetrack, bathed in garish lights so bright you felt the heat of them on your skin. The elevated track circled the pavilion, and the screams of riders spiraling precariously down it on gravity-driven horses hinted at a thrill I would never experience: it cost fifty cents apiece to get into Steeplechase Park, and my mother had put all her spare money into renting our bungalow. Lips pursed around her ever-present cigarette, she paused with my brother and me as we stared at the careening bodies of the wooden horses, neon glinting off their shiny paint.

“Some ride,” she said.

We were too mesmerized to respond.

Each night as we climbed into bed, our mother asked, “Are you having fun?” My brother, as affectionate and exuberant as a puppy, hugged her and kissed her again and again, shouting, “Yes, yes, yes!” My mother’s eyes met mine over his head. I was her difficult child, wiry and fidgety, hardened by the streets, possessed of a premature adolescent angst, savvy to the ways of poverty. I saw in her eyes a plea for forgiveness, because of all she couldn’t give us. I put my arms around her. “Yes,” I said. “More fun than I’ve ever had.”

Though I haven’t been there in many years, I’ve begun to experience an inexplicable need to see Coney Island again, as compelling as the hunger I once experienced as a child.

“I need to go,” I tell my husband.

“Then let’s go,” he answers.

We leave our house in Maine before dawn. It’s a five-hour trip to New York City. We don’t listen to news, only music. We talk about the unusually warm weather; my husband’s upcoming business trip; my insidious, low-level depression of the last few months. We don’t talk about Iraq and the growing body count of American soldiers and Iraqi civilians, Abu Ghraib and the politics of interrogation, my flashbacks to the war-torn sixties and my brother’s death in Vietnam. The sky brightens as we travel south into the waking day. The temperature climbs. We shed coats, then sweaters. It’s December, and trees on front lawns are trimmed with tiny lights, Santa and his reindeer marooned on several roofs. Wind-whipped American flags provide spots of color in the drab landscape. Finally we’ve arrived.

Coney Island both is and isn’t the same. The past and present live side by side here: fields of rubble and new developments crowding old houses that huddle in acceptance of the inevitable. But then there’s the boardwalk and the foam-capped ocean stretching like a blue quilt to the horizon.

Graffitied boards are nailed over storefronts. Faded signs advertise knishes, arcade games, psychic readings. A surreal cityscape of rides is bedded down for winter, all chrome and rust and peeling portraits of leering clowns. The wooden planks beneath our feet are splintered at the edges and spotted with rot, the iron railings lining the boardwalk tarnished. Trash cans overflow. Candy wrappers blow in a crackling ballet down the littered beach. Flags throw fluttering shadows at our feet. My husband, whose childhood world was one of neat suburban lawns, tidy houses, and immaculate cars, has never seen anything like it. He’s a tourist here. I’m home.

I see Coney Island through my husband’s eyes: so destitute, so tawdry. I cannot describe to him the ferocity of color and noise and irresistible, cheap jubilance that once enticed the working poor to come here, sprawl on the beach, plunge into the chilly ocean, scrape together a pocketful of nickels for games and rides.

“It was glorious,” I tell him, defeated. “It was what we had.”

“It’s winter,” he says, trying to soothe me. “Everything is shut down.”

His kindness embarrasses me. So does my obsessive need to come here.

We stare up at the soaring metal remnants of the parachute jump, a skeletal tower flaked with rust. The frame of an old roller coaster rises beside it like the desiccated bones of some prehistoric beast. I remember the bustle, the waiting lines of kids pushing and daring each other, girls giggling and boys swallowing fear in a macho display.

“Let’s sit in the sun,” my husband says. He leads me to a bench, and we rest our feet on the metal railing. The tide nips at the shore like a timid animal, and the smell of ocean is tinged with the odor of rancid trash. Shrieking children run along the boardwalk, trailed by watchful parents. Elderly couples, bundled in heavy sweaters and wool hats, walk arm in arm. I close my eyes and listen to the bits of conversation swirling around me: English, Russian, Yiddish, Spanish. I’m drowsy. The still-familiar sounds and smells of the beach and the taste of the air transport me. I feel myself teetering on a precipice of time, as if I might fall into the past and be unable to climb back into the present.

“Tell me about being a kid here,” my husband says.

My eyes snap open, and I look at him. His face is shaded by the visor of his cap, legs stretched out across the planks.

“Rode my bike. Played games in the arcades when we could get a couple of nickels.” I smile. “Ate hot dogs at Nathan’s.”

He gives a mock shudder; we’ve been vegetarians for twenty-five years.

“Who knew?” I shrug. “Back then it was meat, butter, and cigarettes.”

“What was it like in its prime?” he asks, pressing me.

I stare out at the horizon and tell him about the screams drifting down from the parachute jump; pink wisps of cotton candy that melted on your tongue; the smooth glide of a skeeball up a narrow alley and the excitement of getting it into a fifty-point hole; rides we rode when we could find, or steal, the money. I hesitate, then force the words out: “And Steeplechase Park.” My voice breaks. In my mind I see the sinister smiling face above the entrance to Steeplechase Park’s Pavilion of Fun.

My husband takes my hand and says quietly, “Steeplechase Park? It’s gone, right?”

I nod. “We rented a bungalow in Coney Island for a week one summer when it was still here.”

He’s astonished, knowing the poverty of my childhood: my mom a single mother with a sixth-grade education supporting my brother and me.

My brother, the gentle child.

On our last day in Coney Island, my mother, flushed with pleasure, surprised us by counting out enough nickels, dimes, and pennies for us to go to Steeplechase Park.

“I’ll wait for you over there,” she said, pointing to a spot on the mobbed beach.

“Come too, Ma,” my brother begged.

She shook her head. “Just enough money for two kids.” She looked over his head at me. “You,” she said. “Take care of your brother. Don’t let him get hurt.”

I nodded and took his hand.

We waited impatiently on the long line. I refused to look at that fiendish smile on the giant painted face above the entrance, watching instead the wooden horses and their riders flying by overhead. At the ticket window a teenage girl with brilliant blue eye shadow exchanged our money for passes. We stepped through the gate into a swirl of color and noise. Everyone was infused with an expectant, jittery energy, eating dripping ice cream, running from ride to ride, waving passes and jockeying for position on line. But there was only one ride we were interested in: the Steeplechase. We pushed our way through the crowd, showed the man our passes, and got on another line that snaked along the wall. While we waited, we assessed the eight horses as though they were alive. When it was our turn, we ran through the gate, wanting first choice of steeds. Adults pushed past us, crowding us out, but my brother stopped in front of a shiny brown horse with a flying mane and wide eyes.

“This one,” he told me confidently. “This one will win.”

Neither of us understood the mechanics of the race: that the inside track was the shortest, and that the heavier adult riders went faster. We thought we could triumph by sheer force of will. We climbed on, and my brother curled his arms around my waist. I held tight to the horse’s neck as it began to move. We were thrilled by the whir of the chains that pulled the wheeled horses to the top on metal rails. Gravity would carry us from the crest to the finish line. I drifted into a dreamlike state where everything assumed exaggerated importance: the hum of the crowds beneath us, the sea gulls calling overhead, the smell of sauerkraut drifting up from the boardwalk below. When we reached the peak, the chains ended. For an instant we teetered at the brink; then we plunged down.

My ears filled with the tuneless whistle of the wind. My brother’s arms squeezed my ribs, and he cheered on the mechanical horse, his breath puffing hot against my neck: “Go, go, go!” We flew along through the sharp, salty air above the crowd, a blaze of heat slashing my shoulders as we passed through a ray of sun. Screams from the nearby parachute jump mingled with our shrieks of joy. As we rounded the loop, my legs gripped the wooden horse, and the wind stung my face. I had never felt such freedom, such immersion in pure sensation.

Too soon the horses slowed, the wind lessened, and we arrived at our destination, the finish line. We had come in last. My brother remained seated, patting the wooden horse as if it were living flesh, whispering, “Good job.” Then he dismounted with trembling legs, laughing crazily. “Let’s go again,” he said to me. His curtain of dark hair hung across his forehead, just grazing his wide brown eyes. I nodded and took his hand.

The girl on the horse that had come in next-to-last dismounted, crying with disappointment. The child who’d ridden with her, probably a stranger, ran off. My brother’s eyes filled with sympathy as we passed her. “Good riding,” he told her. She swallowed her sobs, nearly smiled, and said, “Thanks.”

I wished at that moment that I had his generous kindness. But I didn’t.

The exit sign led us to a low-ceilinged wooden shed. The ceiling was so low we had to crawl through on our knees. What happened next is still chilling to me, forty years later.

We emerged onto a long stage filled with screaming people. Clowns with painted faces and gaudy costumes stalked the panicky crowd, like parodies of congenial circus performers, and I thought of the enormous, menacing face at the entrance to the pavilion. Two clowns circled my brother and me, coming closer and closer, waving paddles and rods that buzzed mysteriously. As they advanced upon us, my confusion gave way to terror.

I grabbed my brother’s hand, and we ducked between the two clowns, the stiff edge of a ruffled sleeve grazing my face. Then we collided with a mass of fleeing children, and my brother’s hand slipped from mine. I looked around wildly for a way out. At the edge of the stage, women shrieked and fought to hold down skirts blown up by gusts of air that exposed their panties, garters, and stockings. Taut-faced men tried to be good sports while fending off the clowns, but grew angrier and rougher as the attacks persisted.

I heard laughter and looked down in surprise. An audience seated before the stage laughed and yelled to the clowns, “Get them!” Fingers pointed at children, women, men. A clown jabbed my brother’s leg with his rod, and above my brother’s cry of pain I heard a cheer from the spectators, as though the clown had scored a point for the home team.

I froze, and my stillness drew the crowd’s attention. Heads turned in my direction. Fingers pointed and voices screamed, “Her! Get her!” Pain shot through my body. I yelped and spun around. A clown danced around me, waving his stick in the air. Electric prods! The crowd applauded and stamped their feet as I staggered away from him. He bowed deeply, accepting their tribute. Somewhere my brother howled my name. I dodged among the people onstage, looking for him. Then I saw him, weeping and paralyzed with shock as a clown in whiteface and darkly drawn eyes paddled him. “Run!” I yelled. My brother turned in the direction of my voice, but his eyes were blank, clouded with fear. I felt faint in the overheated arena, and I shook my head furiously to clear it. I was responsible for my brother. I had to get us out of there.

I kicked at the groin of an approaching clown, but he leapt out of the way with a nimble step that made the audience roar. Another one stung me on my calf. My body vibrated with the shock, but I mastered my fear, located my brother, and grabbed his hand. My touch roused him from his fear-induced paralysis, and we ran across the stage toward a door marked EXIT. I heard laughter and the huffing of a clown close behind. My brother lost his balance and fell, and I dragged him along the stage, listening to my own whimpers as if from a distance. My body tingled and ached. Then the floor began to shake, like in a fun house, and I fell to my knees. Stacked barrels wobbled as though about to topple and bury us. I crawled, still dragging my brother, toward the brightly painted exit door. When we reached it, I stood on shaky legs and pulled it open. We were outside, free.

We blinked in the blinding sun. The ground still seemed to heave beneath me. I took deep breaths, again and again, gripping the hand of my brother, who wailed without restraint. Passersby gave us no more than a curious glance. I turned and saw a long line at the entrance to the Steeplechase.

My husband’s face, after I’ve told him my story, is pale and shocked. “I can’t believe that happened,” he says. “Once people knew, they wouldn’t let it go on.”

Before I can speak, three young men of perhaps eighteen, one carrying a thundering boombox on his shoulder, come up the stairs from the sidewalk. They are dressed alike in low-slung baggy jeans, short-sleeved tees, and high-top sneakers with untied laces, their heavy sweat shirts tied around their waists and their thin, muscular arms gleaming in the winter sunlight. One boy has a pack of cigarettes rolled up in the sleeve of his T-shirt. (I am surprised kids still do this.) He pulls out the pack, and they each take one. Then he flicks a silver lighter, and an enormous flame shoots up. They lean forward to light up, a circle of New York Yankee–capped heads. Cigarettes lit, they rest against the railing, fine profiles dark against the sky, voices raised over the strident rap music.

“I’m telling you, man,” the one with the boombox insists as he exhales sharply, “this place really used to be something.”

The other two shake their heads.

My husband moves closer to me so I can hear him and says, “I know you’re not lying, but that was a long time ago. I can’t believe it was allowed to continue.” I see in his eyes not doubt, but the desire to doubt.

“Believe it,” I say.

Later I will look it up and find everything exactly as I’ve described it: the clowns, the prods, the moving floor, the audience that cheered the clowns on — all there. It was called “The Pavilion of Fun’s Insanitarium and Blowhole Theater,” and it dated back to the turn of the century, when audiences had been thrilled by its impropriety. The attraction became seedier as time went on until, by its closing in 1964, it drew mostly an audience of leering older men.

I lean back against the bench and close my eyes, and an irrational anger wells up inside me. Why am I still angry? It was so long ago. My eyes sting with tears, and then I understand my compulsive need to come to Coney Island: I have come here for my brother, to this place where I saved him once. I still want to save him, but he’s gone, killed in Vietnam at the age of eighteen, his optimistic vision of the world shattered, the disillusionment expressed in a few letters home.

A flock of sea gulls land and rise and land again in a flurry of flapping wings. With high-pitched squeals they fight over a clam. The sunlight grows hazy as clouds pass overhead. I take a deep breath, open my clenched fists, and stare down at the beach, the people walking along the water or reading on lounge chairs. Two small children, watched over by a woman who looks too young to be a mother, challenge the waves to wash over their sneakers, then leap back. A teenage couple threaten to throw each other in the water. Everything is normal.

“I guess you never went there again,” my husband says finally.

“No.” My laugh is strange to me. “We went whenever we had enough money.”

He’s astonished. “But you knew what would happen. I don’t understand.”

“We figured next time we’d be quick enough, smart enough. We thought we could get out without paying the consequences,” I say flatly. “We believed it no matter how many times we were proven wrong.”

News of the war in Iraq suddenly blasts on the boombox, and the boy carrying it fiddles with the tuner until he finds another rap station. He’s about the same age my brother was when he died, probably as poor as we were. It’s mostly the poor who join the army, I think bitterly. The poor who fight, the poor who die.

“I’m telling you, man,” the one with the boombox says again. “No bullshit. My grandmom told me. Billions . . . no, trillions of people used to come here. You know: eat, go on the rides, do shit. And this,” his slender finger points to the intricate tower behind us, shorn of its faded parachutes, “kids would wait for like an hour to get on it.”

They shake their heads as they inhale smoke from their cigarettes.

“No bullshit,” the boy says again, insistent and loud over the music. “That ride would hit the top —” he smashes a fist against his hand — “and you’d go down in a parachute, like in the air force or something.”

His friend punches him lightly on the arm and says, “Let’s go. I’m hungry.” I glance at my watch: nearly noon. The three walk away with loose, long-legged strides. One dances on the edge of the boardwalk for a moment, all elbows and hands waving in the air; then they vanish down the ramp.

I stand and pull my husband up by the hand. I want to get out of here. I want to stop thinking about war. I want to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, or see a movie, or take a walk through Central Park. My husband and I head to the car, past the boarded-up arcades, the custard stands and food booths closed for the season, the stretches of rubble. At the roller coaster we pause for a moment. Whole sections of it have eroded. “The structure can’t last much longer,” my husband says. “They’ve got to fix it, or it’ll collapse under its own weight.” I nod in agreement. Our country’s flag waves above us, its frayed edge unraveling in the wind.