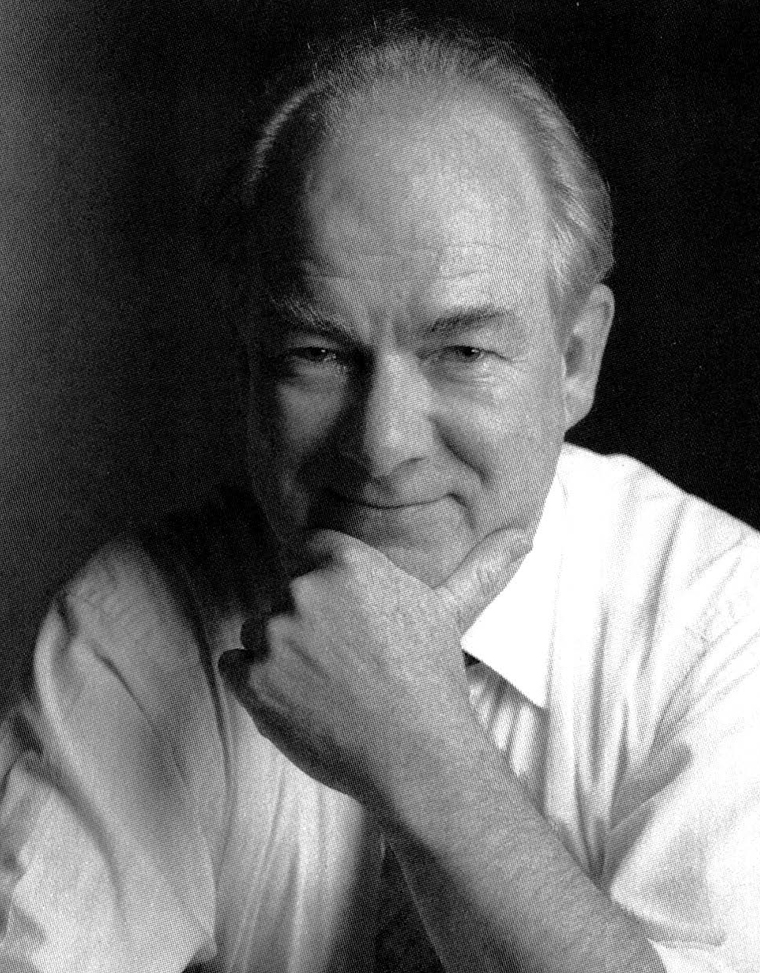

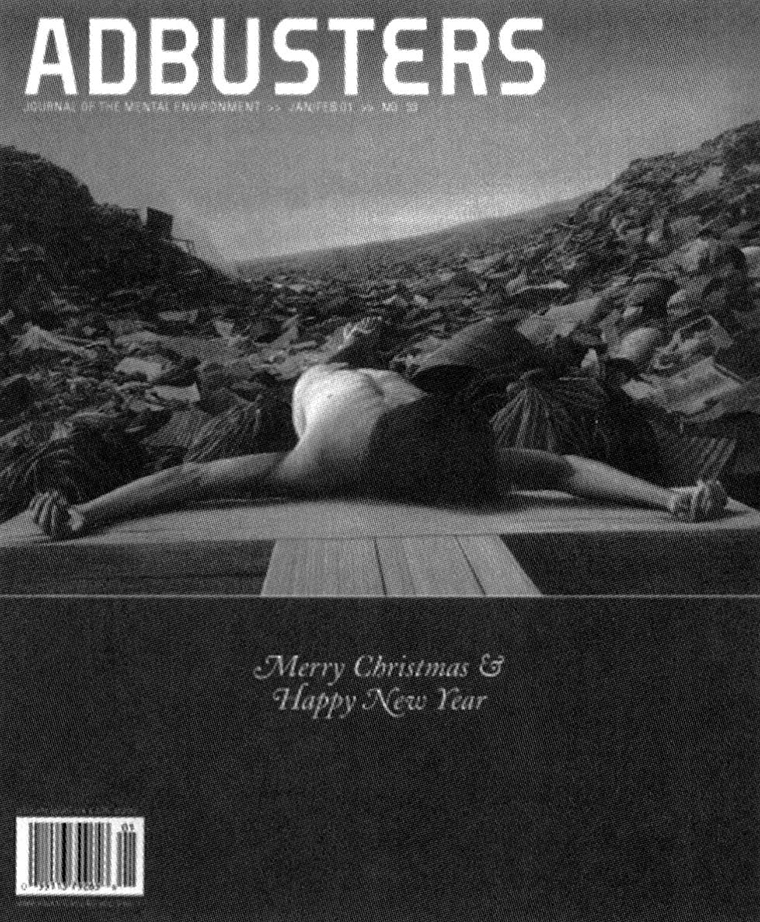

Most Americans haven’t heard of the Media Foundation or its magazine Adbusters: Journal of the Mental Environment, but each day, more and more people get hit by one of its “mindbombs.” That’s what Kalle Lasn — editor of Adbusters and cofounder of the Media Foundation — calls the organization’s “subvertisements”: advertisements aimed at subverting consumer culture.

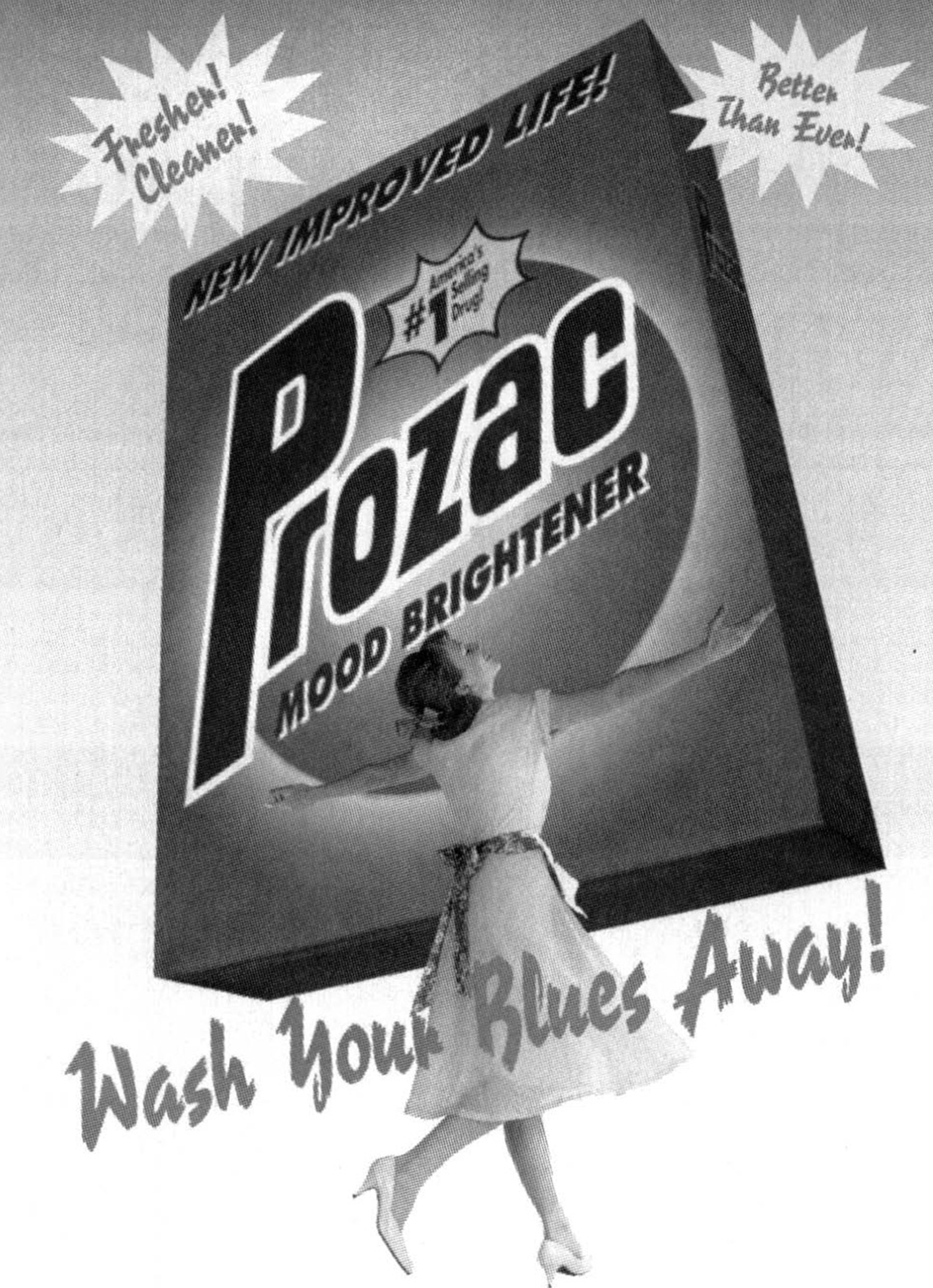

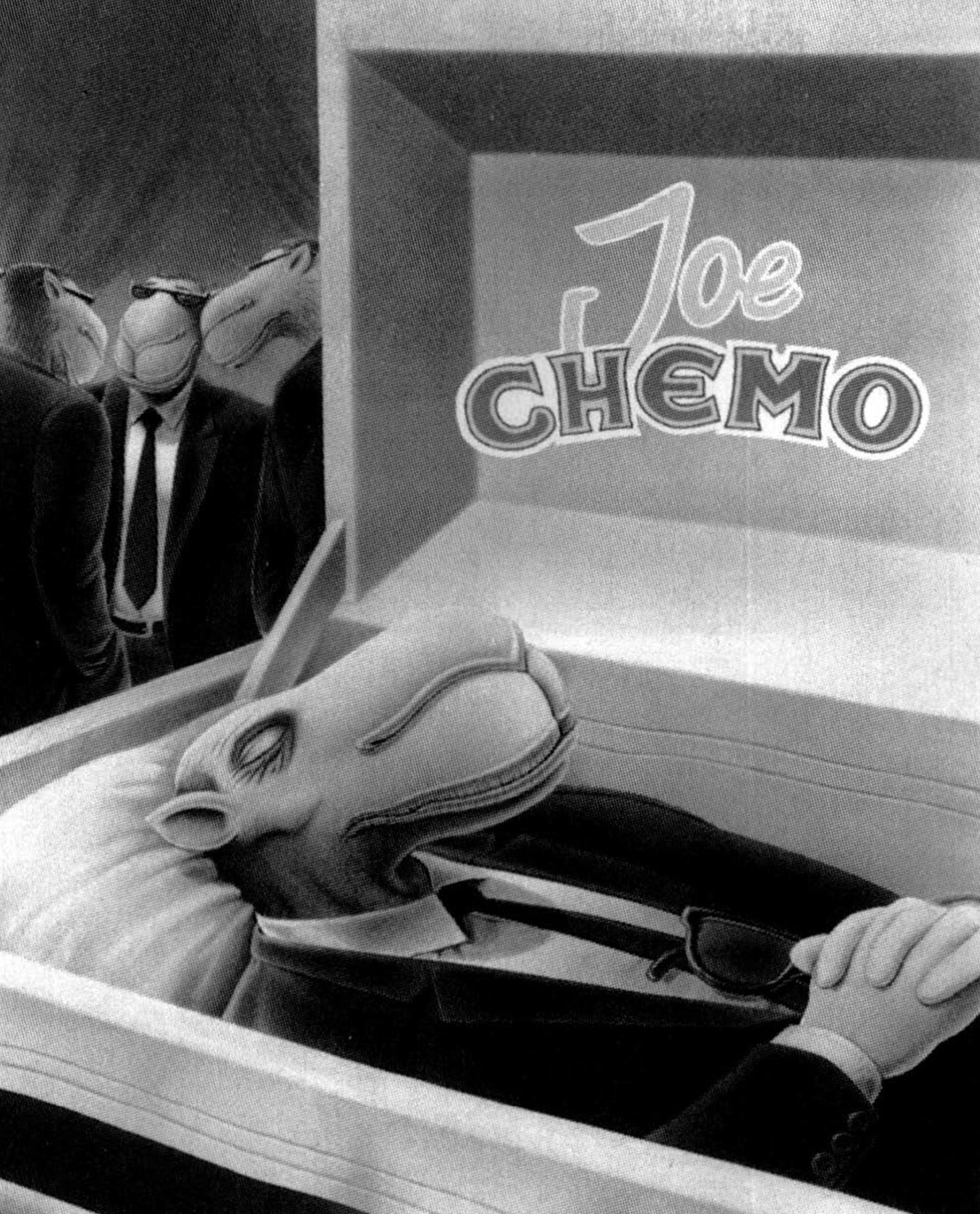

Nearly everyone is familiar with Joe Camel, the cartoon camel used by RJ Reynolds for ten years to sell cigarettes — especially to children, critics said. In response, Lasn’s Media Foundation gave us Joe Chemo, a bald camel lying in a hospital bed with IVs in both arms. Another cigarette-ad parody showed a Marlboro Man look-alike smoking a limp cigarette over the caption “Smoking Causes Impotence.” Still other counterads have taken on alcohol (a battered child seen through a vodka bottle, with the caption “Wipe That Smirkoff”), food monopolies, the fashion industry, and consumer culture in general.

In addition to its advertising campaigns, the Media Foundation sponsors annual consumer campaigns like Buy Nothing Day and TV Turnoff Week. And, of course, it publishes Adbusters, which started out as a little Pacific Northwest alternative publication and now has a circulation of eighty thousand. “It’s an ecological magazine,” the editors say, “dedicated to examining the relationship between human beings and their physical and mental environment. We want folks to get mad about corporate disinformation, injustices in the global economy, and any industry that pollutes our physical or mental commons.”

Central to all of Lasn’s work is the fight against corporate control, not only of politics, but also of our hearts and minds. He has written, “I see Americans and Canadians as having lost spontaneity, verve, individuality and having become consumer drones. We are like rats in a box, and the box is the shopping mall. It’s funny but also very sad. You have to wonder sometimes, ‘Are we really still free?’ . . . Corporations, these legal fictions that we ourselves created two centuries ago, now have more rights, freedoms, and powers than we do. And we accept this as a normal state of affairs. We go to corporations on our knees: Please don’t cut down any more ancient forests. Please don’t pollute any more lakes and rivers (but please don’t move your factories and jobs offshore, either). Please don’t use pornographic images to sell fashion to my kids. Please don’t play governments off each other to get a better deal. We’ve spent so much time bowed down in deference, we’ve forgotten how to stand up straight.”

Lasn was born in Estonia, a republic of the former Soviet Union, in 1942. His family fled the country in 1944, and he grew up in Australia. In the 1960s, he worked as an advertising executive in Japan, until he got fed up with the immorality hidden behind the industry’s claims of “ethical neutrality.” In his thirties, Lasn immigrated to British Columbia, Canada, and took up documentary filmmaking.

He cofounded the Media Foundation in 1989, after he ran afoul of corporate control over the so-called public airwaves. “The lumber companies had begun an ad campaign blanketing viewers with propaganda about how clear-cutting was good for British Columbia,” he says. “All lies, of course. They’d cut so much timber that only 15 percent of the old growth was left.” But when Lasn came up with his own thirty-second advertising spots criticizing the clear-cutting, he found that the networks would not sell him time.

“I came from Estonia, where you were not allowed to speak up against the government,” he says. “Here I was in North America, and suddenly I realized you can’t speak up against the sponsor. There’s something fundamentally undemocratic about private control of our public airways.”

Lasn and his fellow adbusters make no bones about their mission: “to topple existing power structures and forge a major shift in the way we will live in the twenty-first century.” Lasn lays out his strategy for how to accomplish this in his book Culture Jam: How to Reverse America’s Suicidal Consumer Binge — And Why We Must (Quill). He describes in detail how we can go about “uncooling” brands, “demarketing” fashions, and breaking free of our “media trance.”

Lasn lives on five acres of land outside Vancouver, British Columbia, with his family, animals, and gardens. “When I come home after a stressful day,” he says, “I just immerse myself in nature. It rejuvenates me.”

I met Lasn for this interview at the Media Foundation’s offices (1243 West Seventh Avenue, Vancouver, BC V6H IB7, Canada). I liked him immediately. He is warm, frank, and openly revolutionary. We talked all through the afternoon about the insidious effects of advertising and the battle to control the culture.

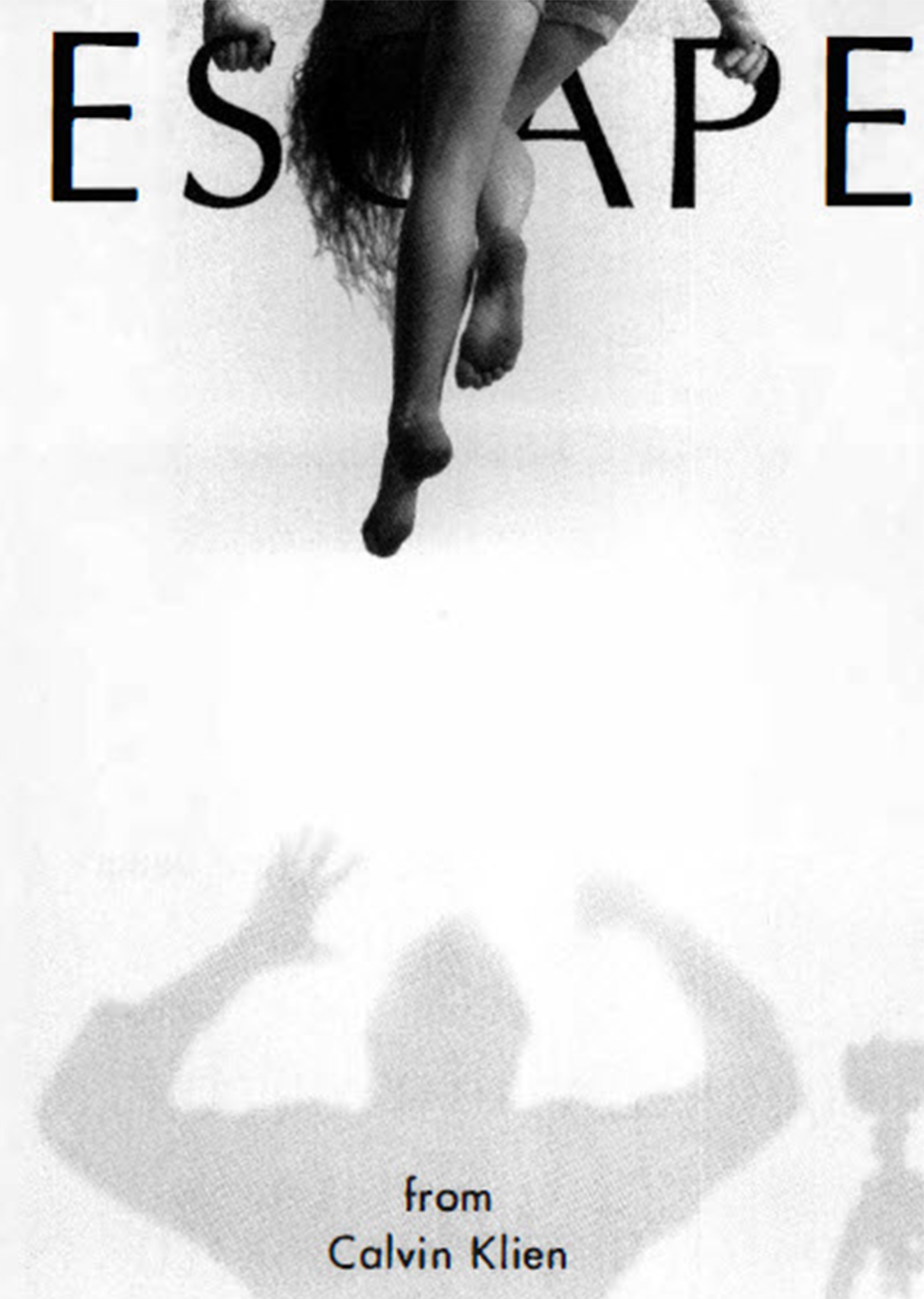

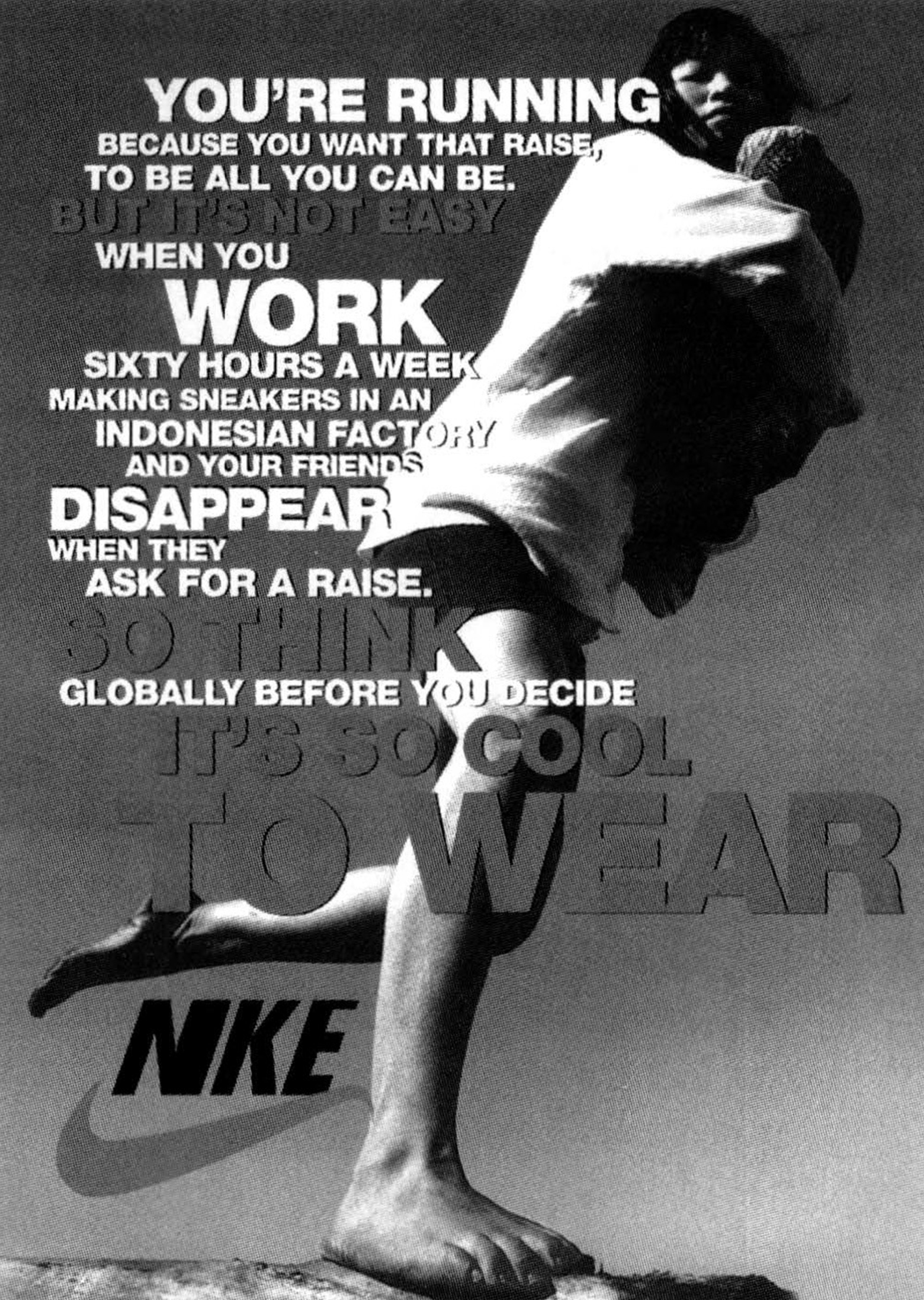

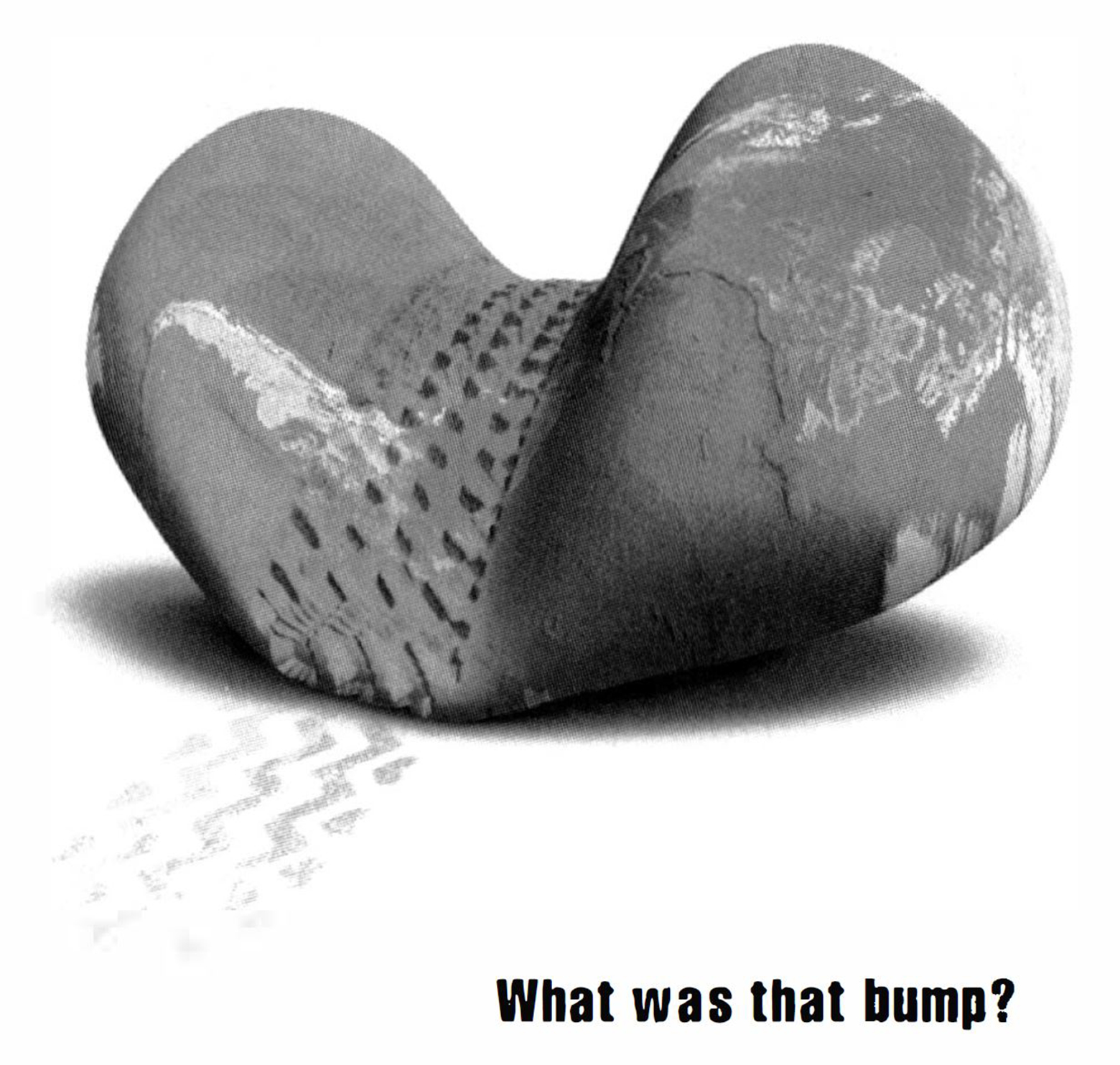

All the images that appear throughout this interview are courtesy of www.adbusters.org.

KALLE LASN

Jensen: What is “culture jamming,” and how did it come about?

Lasn: More than ten years ago, when we first started the Media Foundation, we had a feeling that all the old political movements had run out of steam, and many activists had burned out. Some of us were feminists who’d grown jaded; others were discouraged environmentalists; many were leftists who couldn’t feel that fire burning in the belly anymore. As we plotted and brainstormed, we found that we got most excited whenever we talked about culture.

By that time, we’d put out a couple of issues of Adbusters magazine, and the feedback we’d received told us we were on to something — that the really important battle of the future might not be over race or gender or the environment, and it certainly wouldn’t be that old left/right opposition. What it might be, instead, was the fight to control the culture. The people no longer sang the songs and told the stories and created the culture from the bottom up. The culture was spoon-fed to us now by advertisers, sponsors, and a commercial mass media. Our reliance on cars, our overconsumption, our hollow lifestyles, our lack of democracy — we saw all these as parts of the same package. And the question we kept asking ourselves was “How can we break out of this top-down media trance and start creating an authentic culture from the bottom up again?”

Then we came across the magic phrase “culture jamming.” I first saw it in a New York Times article by cultural critic Mark Dery, but the term actually had been coined long before by the audio-collage band Negativeland. “Culture jamming” seemed the perfect description of what we were trying to do, so we adopted it as the name of our fledgling movement. We became culture jammers — people who opt out of the mainstream and devote our lives to hacking and pranking and provoking and trying any which way we can to break up the seamless charade our culture has become.

The most powerful narcotic in the world is the promise of belonging, and in this culture, we belong by being cool. Our desire for belonging can be satisfied at any store, for the right price.

Jensen: What’s wrong with the way things are?

Lasn: We’ve been reduced to spectators, consumers. We’re discouraged from actively participating in society. We’re just supposed to listen and watch, and then to buy. The mass media keep us in a trance by dispensing a kind of Huxleyan “soma” that drives us to conform and consume: to buy the best cars, to wear the trendiest fashions, to be “cool.” The most powerful narcotic in the world is the promise of belonging, and in this culture, we belong by being cool. Our desire for belonging can be satisfied at any store, for the right price.

American “cool” has become a global pandemic. Communities, traditions, and entire cultures are being replaced by American consumer culture. And it’s killing the planet. It’s a measure of the depth of our consumer trance that the death of the planet is not sufficient to break it.

Culture jamming is about jamming the signals that put us in this trance in the first place. It’s about creating cognitive dissonance, disseminating as many seeds of truth to as many people as you can, with the ultimate goal of toppling existing power structures and changing the way we’ll live in the twenty-first century. Because the way we live has become intolerable.

It’s impossible to live a free, authentic life in America today. We’ve been so deeply manipulated; our emotions, personalities, and core values have become programmed. We sleep, eat, sit in a car, work, shop, watch TV, go to sleep again. I doubt there’s more than a handful of free, spontaneous minutes anywhere in that cycle. Sometimes, in a bank or a mall or a supermarket, I get the sense that real life has passed me by, and I’ll do anything to escape the consumerist cage.

Jensen: What are some examples of culture jamming?

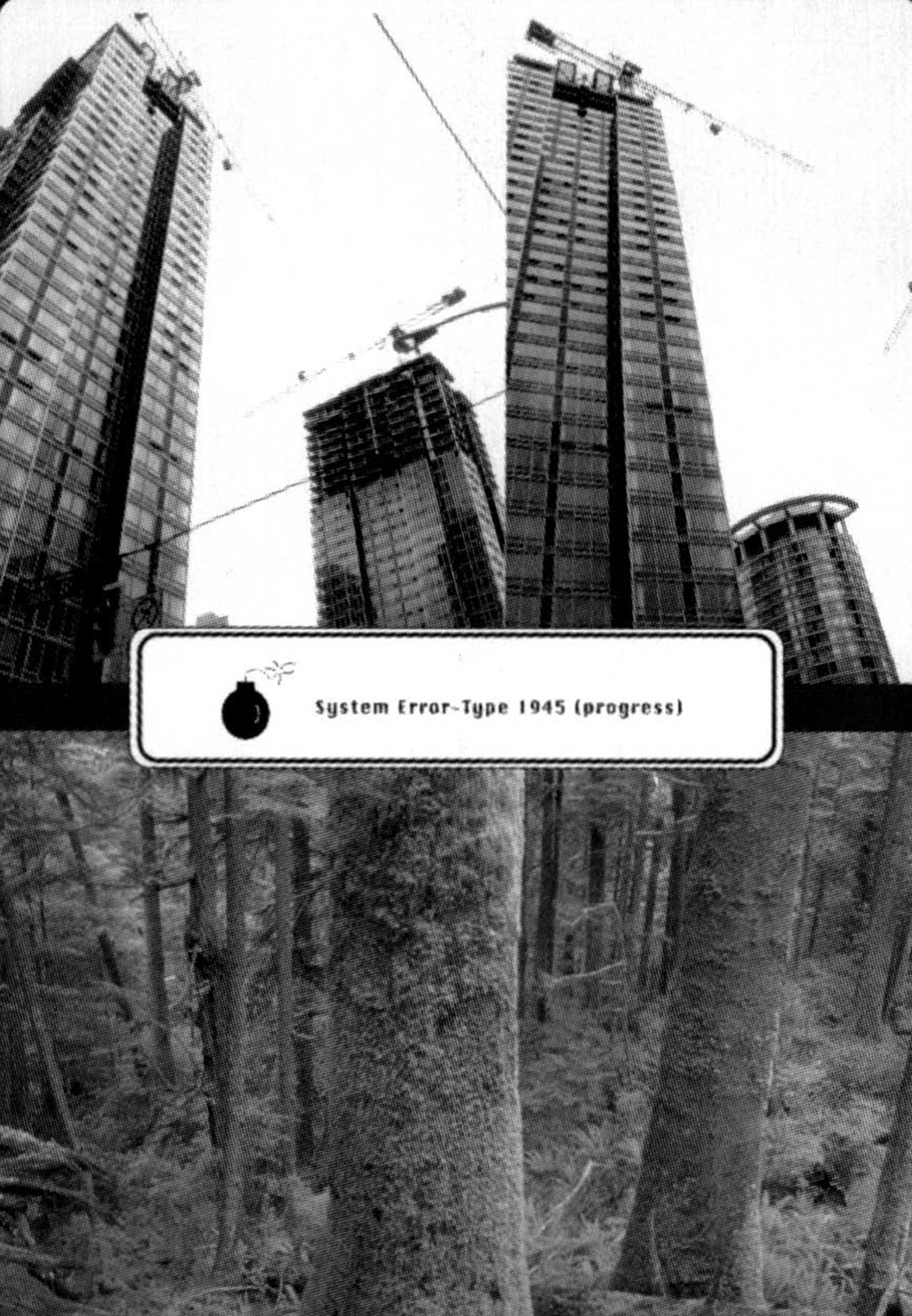

Lasn: One of our best jams so far happened in November 1999, during the “Battle in Seattle” — the protests against the World Trade Organization. We produced a powerful sixty-second TV spot questioning globalization, which aired repeatedly on CNN as the protests unfolded, and on dozens of community and public-access stations in the weeks leading up to the protests. A radio version aired on many college radio stations. We also put up three “System Error” billboards in Seattle to inspire the protesters as they marched by. And activists all over the world who didn’t make it to Seattle visited our Culture Jammers Headquarters on the Internet. It was very exciting and a great example, I think, of a new kind of pincers strategy that combines street action with sophisticated mass-media thrusts.

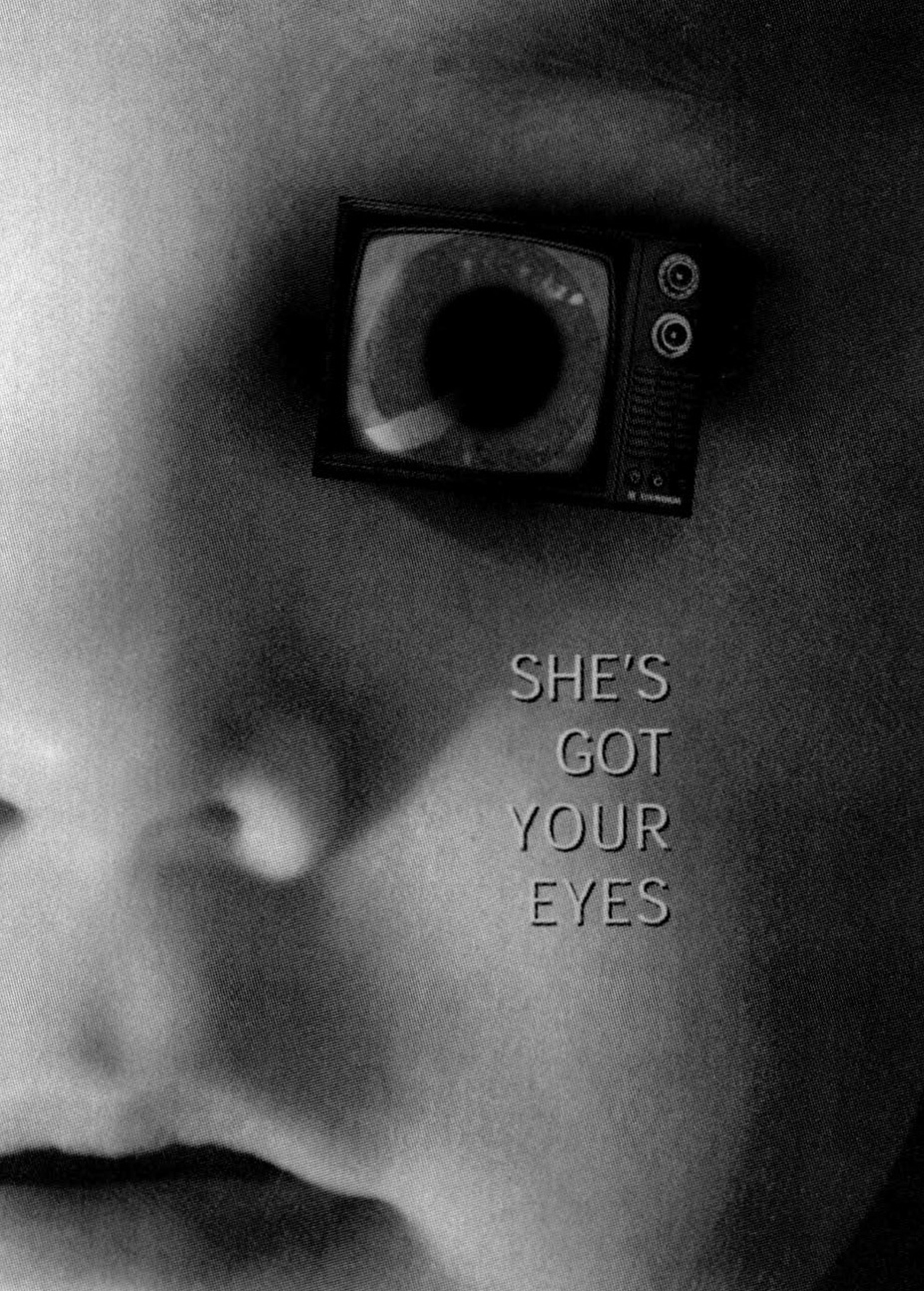

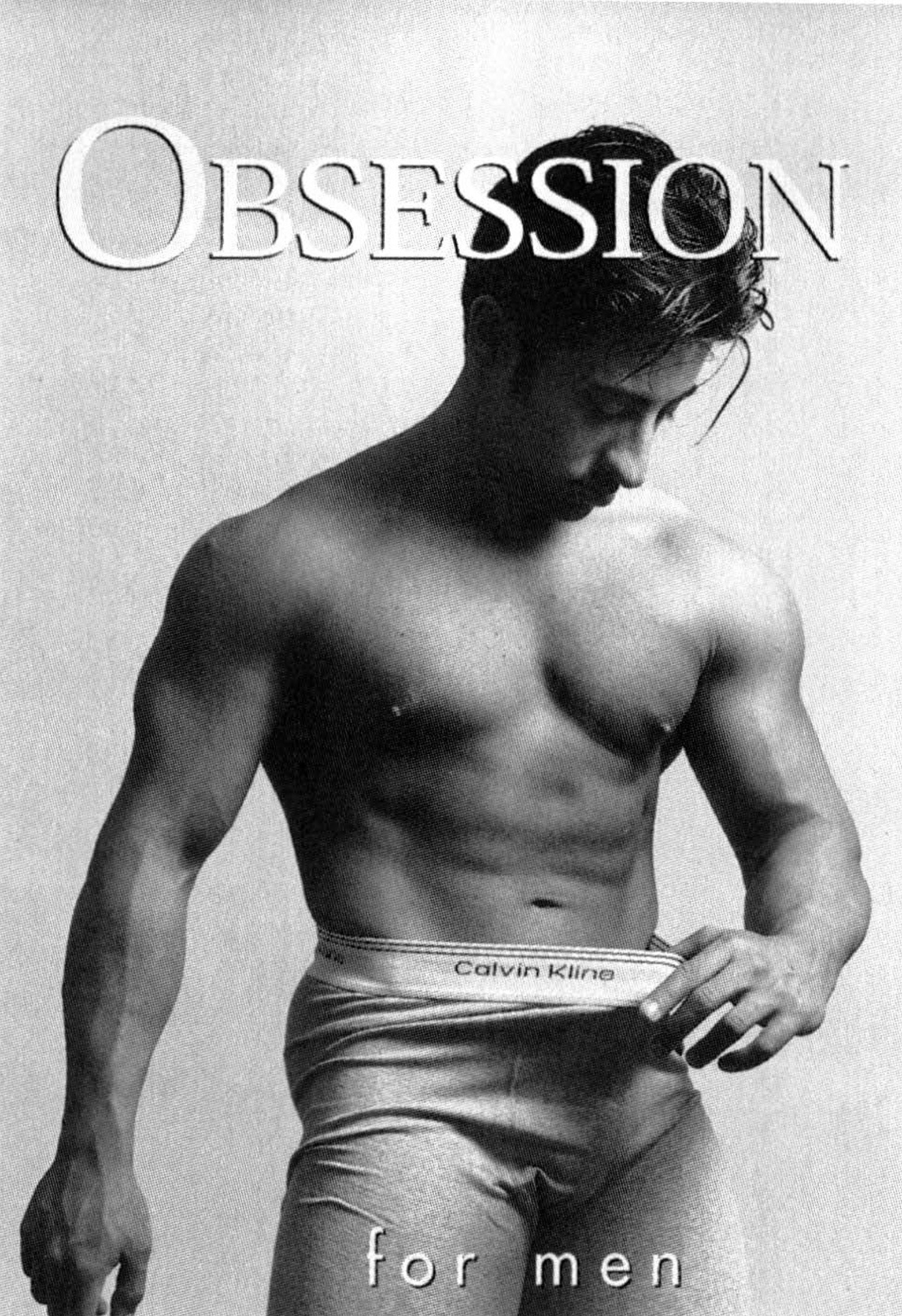

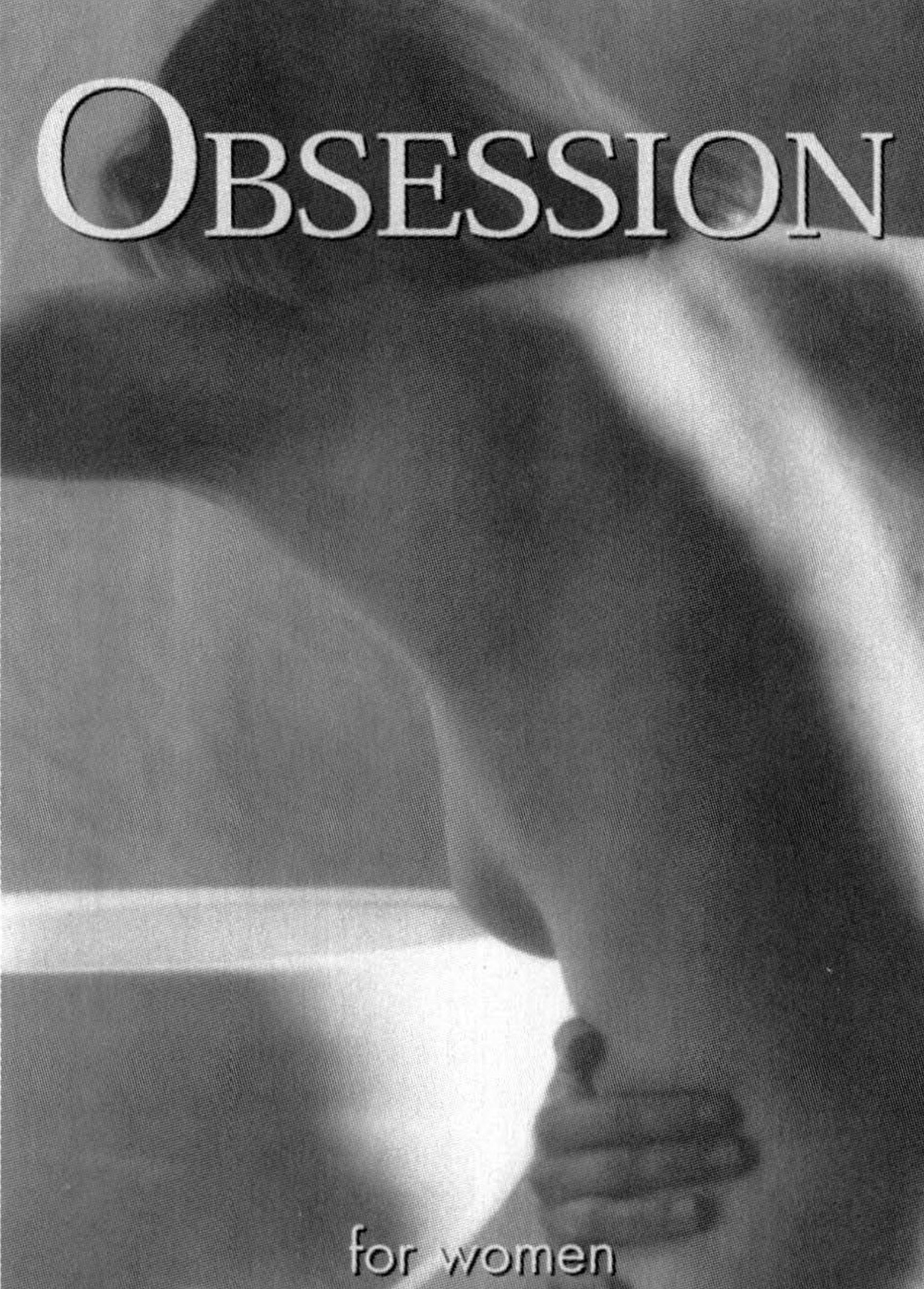

Over the years, we’ve produced dozens of print “subvertisements” and TV “uncommercials.” You may have seen some of them. One shows a male model holding out the elastic waistband of his underwear to peer down at his genitals, with the caption “Obsession for Men.” The “Obsession for Women” TV spot begins with a collage of cool, sexy fashion images and a voice-over asking, “Why do nine out of ten women feel dissatisfied with some aspect of their own bodies?” A model then vomits into a toilet, and the voice says, “The beauty industry is the beast.”

The old activist movements, especially of the left, relied heavily on text — dense manifestoes and critiques, with a drawing or a cartoon thrown in every now and then. Right from the start, we decided that culture jamming would be driven not by text but by images, sounds, and video, which slip easily into the collective psyche.

It’s impossible to live a free, authentic life in America today. . . . Our emotions, personalities, and core values have become programmed. We sleep, eat, sit in a car, work, shop, watch TV, go to sleep again. I doubt there’s more than a handful of free, spontaneous minutes in that cycle.

Jensen: How are Adbusters and culture jamming perceived among mainstream designers and advertising people?

Lasn: Maybe 70 or 80 percent dismiss us as the lunatic fringe, but the other 20 or 30 percent welcome us as a breath of fresh air.

Jensen: That’s not a bad percentage.

Lasn: Many ad-industry people feel disenchanted with the work they do and with the ethical neutrality that reigns in their profession. But advertising is a $350 billion-per-year business worldwide, and, if you’ve got a mortgage to pay, it’s very hard to opt out of it.

Jensen: Is advertising ethically neutral?

Lasn: If you ask ad executives, “How can you possibly work on a campaign for Ford SUVs?” and you begin to explain to them about smog and the paving of the planet and global warming, they’ll cut you off in midsentence with: “That’s not our problem. We’re artists, technicians, highly creative people. We provide a service to clients, and we don’t take sides. Sure, we’ll work for Ford, but we’ll just as quickly do a job for Greenpeace, so stop bugging us about it.” Advertising people are morally detached — and proud of it. That’s why they can, with an untroubled conscience, promote even a killer product like tobacco.

Jensen: That reminds me of what Robert Jay Lifton wrote about physicians at Auschwitz. Many of them, he said, acted as ethically as they could without questioning what he called “the Auschwitz mentality.” Perhaps many of these ad people and designers can consider what they do ethical so long as they ignore the fact that the economic system they serve is grossly unethical.

Lasn: Yes, they have to remain cool, detached professionals to hide the unethical nature of the business. But once you realize that consumer capitalism is by its nature unethical, then you realize that it’s not unethical to jam it any way you can.

Last year, in collaboration with six other graphic-design magazines, we launched a “First Things First” manifesto, which calls for a reversal of priorities in favor of more useful, lasting, and democratic forms of communication — a mind-shift away from product marketing and toward the exploration and production of a new kind of meaning. We asked designers to confront the unprecedented environmental, social, and cultural crises that flow out of the corporate and commercial work they do. It was a curveball to the heart of the profession, and it caused quite a stir. I think almost all the professions — engineering, journalism, medicine, law — need a wake-up call and a period of soul-searching about the role they play in the larger scheme of things.

Many ad-industry people feel disenchanted with the work they do and with the ethical neutrality that reigns in their profession. But advertising is a $350 billion-per-year business worldwide, and, if you’ve got a mortgage to pay, it’s very hard to opt out of it.

Jensen: You’ve called corporate advertising “the largest single psychological experiment ever carried out on the human race.”

Lasn: Yes, ads are everywhere: on billboards and buildings, buses and cars. You fill your car with gas, and there’s an ad on the nozzle. There are ads on bank machines. Kids watch Pepsi and Snickers ads in classrooms and tattoo their calves with Nike swooshes. Administrators in Texas have plans to sell ad space on the roofs of their schools. There are ads on bananas at the supermarket. In San Francisco, IBM beamed its logo onto clouds with a laser; it was visible for ten miles. In the United Kingdom, Boy Scouts sell ad space on their merit badges. In Australia, Coca-Cola cut a deal with the postal service to cancel stamps with a Coke advertisement. There are ads at eye level above urinals. There’s really nowhere to hide. And adspeak — the language of the ad — means nothing. Worse, it’s an antilanguage that annihilates truth and meaning wherever the two come in contact.

As yet, we have absolutely no idea what this constant advertising babble is doing to us. The situation is similar to what we were experiencing at the start of the environmental movement forty years ago, when people just didn’t want to believe that three parts per billion of some chemical in the air or water could be toxic and have all kinds of unforeseen consequences down the road.

Today we are repeating that same mistake in our mental environment, nonchalantly absorbing thousands of marketing messages every day without a second thought as to how, in the long run, they may be affecting us: creating anxieties, addictions, depressions, mood disorders, and other mental problems. The commercial media breed insecurity, because then corporations can offer us ways to buy back our feeling of security, however temporarily. We also need to consider how this corporate branding-and-advertising project influences the way we think about the big social issues of our time, such as global warming, economic globalization, and genetically engineered food.

Jensen: In your book Culture Jam, you say that America is no longer a country, but a trillion-dollar brand.

Lasn: Yes, I think America today is essentially no different from McDonald’s or Marlboro or General Motors. It’s a product image that’s sold to us and to consumers worldwide. The American brand is associated with catchwords like “democracy,” “opportunity,” and “freedom,” but, like cigarettes that are sold as symbols of vitality and youthful rebellion, America in reality is very different from its brand image. The real America has been subverted by corporate agendas. Its elected officials bow down before corporations as a condition of their survival in office. America isn’t really a democracy anymore: it’s a corporate state.

The recent presidential election was a perfect example of the corporate state in action. It was a magnificent spectacle, with a media hoopla that dominated our lives for months. The candidates debated each other, shouted at each other, aimed angry TV messages at each other. And then we all held our breath to see whom the American people would finally elect. But, if you think about it, it was a bogus choice, like choosing between Coke and Pepsi. Both major-party candidates were corporate sponsored. There was never a hint of talk about reining in corporate power and putting the people back in charge.

Jensen: You’ve been specifically critical of the beauty industry on many occasions.

Lasn: The makers of cosmetics and such have altered our concept of what a good relationship and good sex are all about. Our mental environment is saturated with pouting lips, pert breasts, buns of steel, erotic titillations of all kinds. I think these images distort our sexuality and our sense of self-worth. Over time, they actually change our personalities — the way we feel, for example, when someone puts his or her hand on our shoulder, or flirts with us, or asks us for a date.

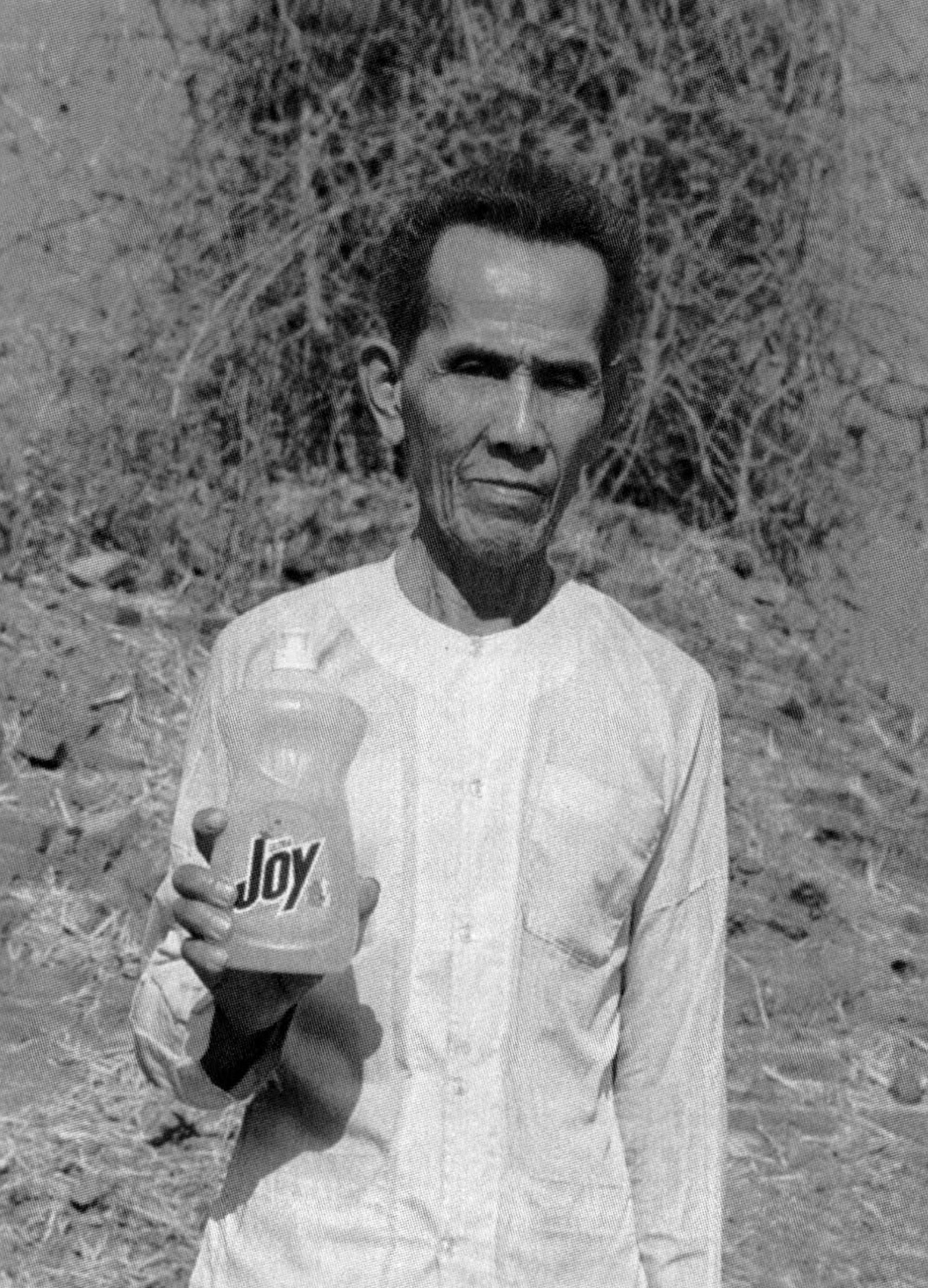

In some ways, I was lucky: I didn’t see television until I was fifteen years old. Even after that, I didn’t watch it as much as kids do now. Children today don’t grow up in a natural environment; they grow up in an artificial, electronic environment that’s corporate-driven, erotically charged, and very violent. Kids growing up in America today are — to use a crude term — getting mind-fucked every day. They associate “life” with cereal, “wonder” with bread, and “joy” with dish-washing soap. What does it do to their psyches to relate sex to everything from cars to bubble gum? It’s not quite the same as sexual abuse, but it’s abuse nonetheless, and the psychic scars last a lifetime.

I think America today is essentially no different from McDonald’s or Marlboro or General Motors. It’s a product image that’s sold to us and to consumers worldwide. . . . America isn’t really a democracy anymore: it’s a corporate state.

Jensen: What led you to become a critic of consumer culture?

Lasn: One of the most profound influences in my life has been a group of European artists, philosophers, and anarchists who called themselves the Situationists. They were the first to use the word spectacle to describe a form of mental slavery where we’re free to resist, but it never occurs to us to do so. In his book The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord says consumer society is a world in which everything has been commodified, where consumers have the illusion of unlimited choice and freedom, but in fact their lives have been reduced to preselected experiences: adventure movies, nature shows, Net surfing, celebrity romances, political scandals —

Jensen: Like Monica Lewinsky.

Lasn: Yes, that spectacle mesmerized America for almost a year.

Jensen: And it was absolutely meaningless.

Lasn: Well, in that particular case, I think there was actually plenty of meaning. But instead of a careful examination of that meaning, all we got was innuendo, lewd jokes, guesswork, and gossip.

Jensen: I’m curious: what do you think the meaning of the Monica Lewinsky scandal was? Because when the world is being killed before our eyes, I don’t care if the President gets a blow job. To me, that’s meaningless.

Lasn: What is meaningful to me is that the President looked the American people in the eye and blithely lied through his teeth. And even more meaningful is how easily the American people shrugged off this insult. That is the essence of the spectacle; that’s exactly how it works: we become so bedazzled and dumbed down and cynical that we allow those in power to manipulate us; not only that, we accept this manipulation as routine. When those in power routinely lie, and we routinely accept it, what sort of democracy do we really have?

The Situationists talked about our lives being “kidnapped” by the spectacle. In the great Situationist text The Revolution of Everyday Life, Raoul Vaneigem argues that the spectacle has made us self-conscious about even our most personal gestures. Our intimate moments are not truly our own anymore, because moments just like them have already been presented to us in a magazine or a movie or a sitcom.

At root, culture jamming is just a way to stop the flow of spectacle long enough for people to remember that they have their own lives. To get your life back, you have to tune out, switch off the computer, refuse to download your e-mail on your day off, break out of habitual routines. When the TV malfunctions, don’t fix it; decide to suffer through the withdrawal. Fight your way out of the consumerist cage. If you have enough guts and self-discipline to make it to the other side, you’re ready to move on to bigger things, such as jamming the culture yourself.

It’s quite clear that you don’t need to match Nike or McDonald’s dollar for dollar to beat them. All you need is the truth on your side and a truly free marketplace of ideas in which to compete . . . We’re going to take on the global automakers, the industrial food giants, the fashion moguls, and the biotech megacorporations, and we’ll beat them just as those earlier crusaders beat the tobacco companies.

Jensen: But how do we deprogram ourselves when, every day, we are still confronted with thousands of plugs for consumerism? How can your advertising budget match Nike’s or McDonald’s or that of General Motors?

Lasn: We don’t need million-dollar advertising budgets to beat Nike and McDonald’s at their own game. Think back to twenty-five years ago, when cigarette ads were still running on TV. Do you remember those brilliant antismoking ads that started appearing? I remember them vividly: the extreme close-ups of the glowing tips of cigarettes; the X-rays of blackened lungs; Yul Brynner, just months before he died of cancer, looking the world squarely in the eye and saying, “Whatever you do, don’t smoke.” Those ads were so compelling, so real, that within a few months the tobacco companies — even though they were outspending the antitobacco crusaders by maybe a hundred to one — were simply unable to compete. For all its financial might, the tobacco industry was crushed and forced to “voluntarily” accept a federal ban on TV ads for cigarettes.

It’s quite clear that you don’t need to match Nike or McDonald’s dollar for dollar to beat them. All you need is the truth on your side and a truly free marketplace of ideas in which to compete. I predict that, over the next few years, TV jammers will repeat that tobacco story again and again. We’re going to take on the global automakers, the industrial food giants, the fashion moguls, and the biotech corporations, and we’ll beat them just as those earlier crusaders beat the tobacco companies.

Jensen: How do you see this information war playing out?

Lasn: I think it will unfold something like this: A few subvertisements will start popping up, as they did on CNN during the Battle in Seattle — a sort of TV graffiti, a low-level “meme” warfare, a meme being an idea or phrase that moves through the culture like a virus. These ads will remind people that the status quo is being challenged, that there exists a strong and committed opposition to the corporate state, consumer culture, and the way the global economy is currently being run.

And then will come the crucial step, the scenario I’ve fervently believed in for the last ten years: we culture jammers will win a dramatic First Amendment legal victory against the TV networks, which for a decade have refused to sell us any airtime for our campaigns.

Jensen: Even when you come to them with cash in hand?

Lasn: Cold cash. We want to buy thirty- and sixty-second spots under the same rules and conditions as Nike or McDonald’s, but the networks refuse to sell to us. They have a policy that says they’ll sell airtime for product ads, but not for what they call “advocacy advertising.” If, however, we win a First Amendment legal action, and the courts declare that freedom of speech includes the right to walk into your local TV station, slap your money on the table, and freely buy airtime, then the meme warfare, the culture war, can begin in earnest. That’s the moment when the mindbombs will start exploding on the evening news, and a new era will be born.

I believe there will be a groundswell of support for our cause once people wake up to what’s at stake: our freedom to communicate with each other. If we, as a society, lose our voice completely, and corporations start doing all the talking, then we’ll be utterly lost. To some degree, this has already happened. Our ability to envision a future collectively has already been severely compromised.

Jensen: Have you approached attorneys about the feasibility of mounting a First Amendment challenge?

Lasn: Yes, and most of them say it’s a very difficult proposition, given that all previous legal actions against the TV networks have failed. But there is cause for hope. We are the first group that has collected letters, faxes, and transcripts of phone conversations with network executives, proving that not just a single proposed thirty-second spot, but whole classes of information about transportation, nutrition, fashion, and sustainable consumption have been systematically kept off the public airwaves.

Jensen: Should the airwaves be opened up so that even the Ku Klux Klan could air a spot?

Lasn: I don’t have a problem with that. I’d rather live in a world where people I dislike are allowed to express their views than in our current system, where we are being propagandized on a massive scale with no real opportunity to speak back.

We want to buy . . . spots under the same rules and conditions as Nike or McDonald’s, but the networks refuse to sell to us. They have a policy that says they’ll sell airtime for product ads, but not for what they call “advocacy advertising.” If . . . we win a First Amendment legal action, and the courts declare that freedom of speech includes the right to walk into your local TV station, slap your money on the table, and freely buy airtime, then . . . the culture war can begin.

Jensen: What happens after you win a First Amendment legal victory against the TV networks?

Lasn: People will feel empowered by the battle of ideas on TV, and, bit by bit, they will come to wonder why they cannot have an even bigger voice on the so-called public airwaves. They will question why they have to pay for access to something they own. In this kind of atmosphere, I think we will find support for the idea of giving some airtime — maybe two minutes per hour — back to the people. I call this “The Two Minute Media Revolution,” a first-come, first-served system of free TV access for individuals, communities, and groups.

In the information age, we need information rights. Race, gender, and environmental rights were fought for and won in previous eras. Now I think we’ll have to fight another great battle to make the right to communicate a fundamental human right of every person on earth.

Jensen: Where would that take us? What do you want?

Lasn: I can’t answer that first question. In fact, I don’t even want to, because once we cast off what my friend Rick Crawford calls “the chains of market-structured consciousness,” who knows where we’ll go and what we’ll do? Why try to predict it?

But I can answer the second question: What do I want? I want freedom. I want to live in a world where I don’t feel oppressed by my TV set, my telephone company, my bank, and the pharmaceutical company that sells me the pills I need to survive. I want to live in a world where human beings, not corporate entities, call the shots — a world in which the people create the culture, instead of having it rammed down their throats. I just can’t stand to live in this consumer world anymore. It doesn’t feel right. I feel hollow, as if I’m not really living.

Jensen: Guy Debord wrote, “Revolution is not showing life to people, but making them live.”

Lasn: Yes, that’s what culture jamming is all about. There’s another Situationist saying: “Live without dead time.” Imagine what that would be like. Or, better still, don’t imagine it; live it.