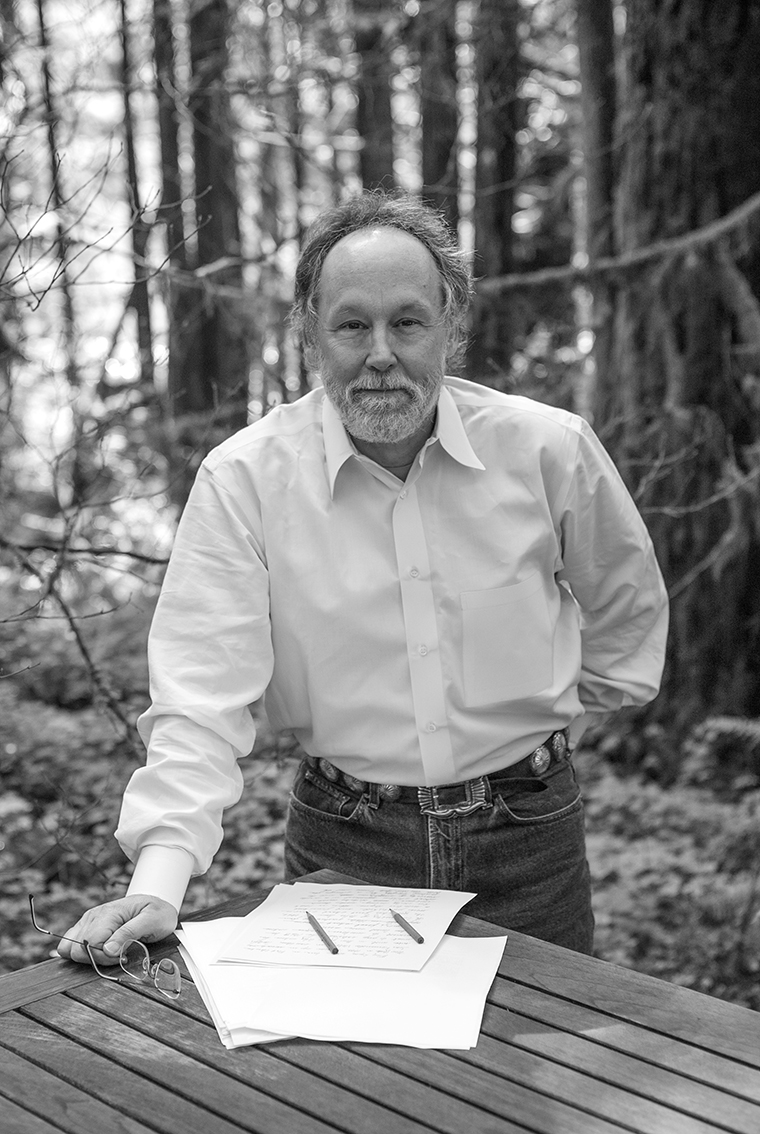

When I arrived at Barry Lopez’s home last fall, tucked in a grove of Douglas firs beside the McKenzie River in Oregon, the first thing I noticed was the prie-dieu, a type of wooden kneeling bench that might be found in a monastery cell, only here it stood alone on a deck beneath the trees. This felt right. Though not overtly religious, Lopez’s writing has a prayerful tone; a feeling of invocation or incantation; a reverence that elevates the mundane. In his hands a raccoon’s jawbone, found in the detritus of the forest floor, might reveal to us something new about ourselves.

I first came to Lopez’s work through his 1998 essay collection About This Life. Whether describing his travels in northern Hokkaido, Japan, or his practice of removing the bodies of animals killed on roadways, he drew me in. Here was a writer I could trust. My appreciation grew as I read more of his work: the essay collection Crossing Open Ground; the National Book Award finalist Of Wolves and Men; Arctic Dreams, which won the award; and his collections of short stories — Field Notes, Light Action in the Caribbean, Resistance. I have read Lopez’s book-length fable, Crow and Weasel, aloud to my three young sons. “Sometimes,” an elder in that story says, “a person needs a story more than food to stay alive.”

When I asked Lopez if I could interview him, in November 2018, he kindly offered me a place to stay in his guest house. He was nearing completion of a major new work of narrative nonfiction, a book he’d spent thirty years researching and five writing. The research had taken him to seventy countries in all, from Cape Foulweather in Oregon to Skraeling Island in the Arctic; from a former children’s prison in Tasmania to the ominously named Port Famine at the tip of South America. Throughout these journeys Lopez asked the questions of human identity and destiny that he says have preoccupied him for three decades: Who are we? Where are we going? That book, Horizon, was published by Knopf in March 2019 (barrylopez.com).

For several days that November we hunkered down beside a woodstove and talked. I found Lopez as eloquent in person as he is on the page, and a gracious host, if a bit subdued. He was in the late stages of metastatic cancer.

We spoke each morning until his energy flagged, and in the evenings we shared meals with his wife, the writer Debra Gwartney. Once, before dinner, Lopez drove me up the McKenzie River and showed me where salmon spawn. A year earlier a bear had killed and eaten all the salmon there, and we wondered aloud if the females had been able to lay their eggs before the bear had gotten to them. We stood for a while in silence and watched twilight settle over the water. On the way back Lopez pointed out the house of a man who had been a full-time bear hunter. Local timber companies used to hire hunters to eradicate bears, who would sometimes strip bark from young trees the companies owned. This is the land Lopez inhabits and writes about: a world of beauty and loss, often in the same breath. “That was a very precious moment,” he told me the following morning before I left. “Two men standing quietly in the dusk beside the river, talking about bears and salmon.”

Though it would be a mistake to think of Lopez as merely a “nature writer,” his books, essays, and stories all speak in some way to our relationship to the more-than-human world. Lopez also explores humanity, including our capacity for evil. The January 2013 issue of Harper’s Magazine featured his essay about the repeated sexual abuse he’d experienced as a young boy. This potential for abuse, Lopez tells us, is also part of our story, and must be exposed and reckoned with.

Running throughout Horizon is the question of human survival. The multiple threats we now face, especially the very real possibility of climate disaster, expose the tensions between human aspiration and ecological reality. Perhaps what is most needed, Lopez suggests, is for us to lament what we’ve destroyed, but also to praise and love the world we still have. “Mystery,” he writes, “is the real condition in which we live, not certainty.”

BARRY LOPEZ

Bahnson: I want to ask you about travel. You’ve traveled to more than seventy countries and repeatedly to every continent. You’re not going as a tourist. What’s the word that describes who you’re going as: Pilgrim? Witness?

Lopez: I don’t see my work as a pilgrimage. I see myself as innocent (rather than ignorant), as a student, so in that sense as a pilgrim, but I don’t know what drives that part of me — the urge to go, to see. I am now managing an illness that restricts my ability to travel. So, I’m asking myself now, what might come along in place of these frequent, far-flung sojourns? The kind of travel that doesn’t appeal to me at this stage of my life is going abroad to see famous things, you know? When I was seventeen, I went to see firsthand much of the iconic life of Europe that fed into North American culture: museum collections, cathedrals, the Champs-Élysées, Rome, and London. I loved doing it, I remember it fondly, but I don’t have any interest in doing this again.

Where I want to go is to the places my culture considers undistinguished. I have a kind of classical mind — as opposed to a rococo mind — one that would not be at home in a jungle. I tend to end up in deserts or in the Arctic or out on the ocean. It’s the “big open” that engages me. It’s a bare stage for me to work on. I can’t find that in a city. Others can. Also I can’t feel at home if I’m not physically engaged with the world. I don’t want to be inside a building looking at things in display cases. I want to be outside, watching things that will never appear in a display case. But now I’ve got to figure out some different way to do all this. I will. I’ll figure it out, how to fulfill this yearning. Perhaps, then, my work actually is some kind of pilgrimage. Heading for the source. But I don’t yet have a vision of what would satisfy the urge to go and see. I have to discover that “destination,” I guess, on another scale, if I’m no longer going to travel internationally.

I was in Japan in 1984, the guest of a Japanese novelist who lived south of Tokyo, in Kamakura, I think. There is a large statue there of the Buddha, a Daibutsu. I wanted so to see it. These Daibutsus are hugely important in the spiritual and psychological life of Japanese people. I arrived there on a bullet train from Tokyo. I bought a ticket at the little kiosk, came around the corner of a wooden fence, and saw the statue. I nearly sank to my knees. I could barely stand. It was a vision of great holiness, one that had never surfaced in my pretty-good education. Maybe in a moment like that, when I feel such gratitude because I am able to see this, maybe that’s part of a pilgrimage: to deliberately go see those kinds of things. I did the same thing once in Bamyan [Afghanistan], the place where the Taliban destroyed the two Buddhas, a husband and wife. I had the opportunity when I was in Kabul to make that journey with a couple of armed escorts. When I said I was traveling to Bamyan, someone asked, “Why are you going? The Buddhas there were destroyed.” Are you crazy? I thought. Seeing the now-empty grottoes where they once had been would be as informing as having seen them several years before that, when they were whole.

I’m trying to be helpful here about your idea of a pilgrimage.

I can’t feel at home if I’m not physically engaged with the world. I don’t want to be inside a building looking at things in display cases.

Bahnson: I guess what’s behind my question is the feeling, as I read your work, that you’re on a spiritual quest. And it seems like you’re coming right up against what are religious questions, spiritual questions. In particular you’ve spoken about the numinous quality of the more-than-human world, which sometimes appears to be looking back at us. In Of Wolves and Men you say, “The wolf exerts a powerful influence on the human imagination. It takes your stare and turns it back on you.” And again in the introduction to Home Ground, you write, “One must wait for the moment when the thing . . . ceases to be a thing, and becomes something that knows we are there.” In Horizon you speak of your belief in the land as “sentient and responsive.” That’s not a view most people would express in public, for fear of sounding woo-woo.

Lopez: Right.

Bahnson: What is it that is looking back at us through the eyes of a wolf, or from a particular landscape? Some would name that God, or some other word for the Divine. How would you name that?

Lopez: I would say it’s an encounter between the two sides of a lopsided divorce. It’s a breach, you know. The agricultural revolution was a breach, a divorce. The industrial revolution was a worse breach. The surrounding material world was relegated, in both these instances, to the position of an employee, even a slave; a source of entertainment; a storehouse for natural resources. When wild animals look back at you, I can imagine what they might be thinking if your defense for the massive changes you’ve engineered in their world, and are responsible for, is “But look at this beautiful world we’ve built.” Many divorces are characterized by incredibly lopsided thinking and misapprehension. I believe one of the reasons our lives are so difficult today is because of the separation from the rest of the natural world that we’ve insisted on having, our insistence on the primacy of human life. Human history, you know, is but one dimension of natural history. It’s not the other way around.

If you can imagine a divorce in which only one member of the dyad — modern humanity — made the decision to create a breach, and then enforced it, you can begin to understand what the growing malaise in human culture is about. It occurs to humanity that it has lost its spouse. That’s metaphorical, of course. But if you imagine what happens when divorce is forced on just one person, then you can begin to understand why traditional people are reluctant to make that same adjustment. They don’t want the breach. They see the destructive injustice. Why accept a separation from all the rest of creation? Everybody I spoke with in villages across the Arctic in the seventies and eighties, when I asked them to offer me adjectives for people in my culture, the one word I heard repeatedly was lonely. They see us as deeply lonely people — and one of the reasons we’re lonely, if you agree with that, is that we’ve cut ourselves off from the nonhuman world, and have called this “progress.”

Bahnson: So perhaps those moments of numinous encounter are really moments of regrounding ourselves in reality?

Lopez: Yeah, reconnection. It’s reconnection. And this brings us around to the issue of memory. I recall every day the moments of primal contact I’ve experienced with the nonhuman world — with pronghorn antelope and wild salmon and scarlet tanagers — and with the nonhuman world’s most intimate and knowledgeable interpreters: indigenous people. The memories regenerate me; they boost my desire to try to work in my writing as a mediator of some sort between the dehumanized natural world and my own acquisitive culture.

Bahnson: What, specifically, are those moments of primal contact?

Lopez: They’re private moments of animated contact with the world outside the human. Watching animals, just sitting with a friend and watching animals for a long time, not saying much. I think of those moments at Lake Clifton in Australia that I describe in Horizon: standing out there on the boardwalk with two friends, drinking it in. Or in Antarctica, at Cape Crozier, watching the emperor penguins. It’s not about interpreting or “figuring out” what these wild animals are doing. You just give in to the spectacle. You become a participant.

Bahnson: It seems like what you’re offering the reader is not “Hey, you guys should get over to Antarctica; it’s really amazing. Check out these penguins!” Instead you’re helping them see that we can have those encounters every day when we step outside in the right frame of mind.

Lopez: Some people can. There are a lot of people living lives of bare-minimum survival who don’t have access to such events. People like you and me are in constant danger of forgetting the rarity of the gifts we’ve already received, the memory of which can make our lives easier. Because we see the value and the holiness in it, we want to urge others to participate. But others are just trying to get food on the table. They didn’t choose their situation. In a traditional village, food arrives on everybody’s table if it arrives on one table. Maybe you’re not going out and “earning” your own food; maybe that’s not a skill that’s good enough in you, but others will provide it and never mention it. It’s easy to see how that works on a small scale, but we don’t like small scale. We like Cairo and Tokyo scale. So, can we do this?

My question for myself in Horizon was “Can we still make what we have work, or is this the end?” The conceptual challenge now is to imagine something entirely new.

Bahnson: “This” being the human project?

Lopez: The human enterprise, yes. I think — and I hope you agree — that Horizon follows that path. I’m trying to reiterate the possibilities that are held out to us by various horizons. I’ve seen horrible human behavior in so many places. I see the pleasure some people take in injustice, and I see their appetite for the violent enforcement of prejudicial beliefs. The question this forces on us is “Are we ever going to outgrow this hatred of the Other?”

Bahnson: Is what comes up in you an open-ended question about the direction in which we’re headed, or are you feeling despair?

Lopez: No, I don’t feel despair. What I feel is anxiety, having put myself in a place of responsibility by writing a book. I have chosen to be responsible in some way, in Horizon, for the situation we’re living in; to be implicated. There are millions of people like me — writers, painters, dancers, photographers, composers — who have chosen over a long period of time, like fifty years, to pursue the arts in a way that is not self-serving, self-celebratory. Maybe it’s arrogant of me to say this. But I believe there is a difference between writing for, to put it crudely, money and fame and writing for the health of the human community, for its survival. There’s a man who’s been in a formal sense an elder to me for thirty-eight years, and when I asked him about holding that position in a community and the discouragement you can feel, he said, “The only thing to understand is that you can never quit.” You can’t ever say, “Well, this is hopeless. We’re all going to go down the tube.” No. It’s not hope or despair or optimism you’re searching for; it’s a belief in humanity. Those feelings have, for many, developed under the umbrella of organized religion — being in service to a thing greater than the self.

I do go through periods of time when I’m not optimistic, but I remain provisionally hopeful. And then there are other periods when I think I have no reason at all to be hopeful.

When wild animals look back at you, I can imagine what they might be thinking if your defense for the massive changes you’ve engineered in their world, and are responsible for, is “But look at this beautiful world we’ve built.”

Bahnson: You’ve confronted the darkness you see on the horizon with anthropogenic climate change. How do you talk about this with audiences? People need to know what’s coming, yet if you overwhelm them with depressing news, they might freeze. How do you strike the balance between educator and artist?

Lopez: Whenever I speak in public, I write out a new talk. I begin by stipulating, with a modulated voice, that things are way worse than we imagine. And I offer some examples: the collapse of pollinating insect populations; the rise of nationalism; belligerent and ignorant narcissists like Donald Trump; methane gas spewing out of the Siberian tundra. You’re saying to everybody, “Let’s take off the rose-colored glasses now and see what our dilemma really is.” And then the second part of the talk is an evocation of the healing that is necessary and possible, a gradual elevation of the human spirit. It’s about the mobilization that is needed and which is within our reach. Then people know you’ve spoken truthfully, and you have evoked in each person a desire to help, to take care of their families, to have self-regard. I see this pattern in every talk I give. To remember, geographically, exactly where you are speaking that night, and to know whether there might be a full moon outside the building; to offer that sense of immediacy and groundedness; to underscore the specificity of the moment; and to be sure that you implicate yourself in the trouble. It all helps in these situations. If you attempt any version of “I know, and you don’t” or “This is not my fault” or “I am the holy messenger, and you’re the fools,” the evening ends in darkness. You have to be in it with them.

I think of Brahms’s Requiem or Mozart’s Requiem here. Certain composers really knew how to effect this catharsis, to limn the darkness and then, through the arrangement of chords and tonal values, bring us up into a place of exaltation. That’s why that music is still so important. Do you know the work of John Luther Adams? Listen to Become Ocean, the piece he won a Pulitzer for. John and I met in 1983, and we’ve been talking ever since about what music does, what language does. We’ve taught each other. He’s one of a handful of people who know what we’re dealing with environmentally and culturally, even though we don’t always have language for it. It really is a kind of holy work. It’s not self-promotion but a place you find yourself in as an artist at a time when that kind of work is desperately needed.

Bahnson: The Estonian composer Arvo Pärt has also been important to you.

Lopez: He’s scary good. He is a legitimate heir to the spiritual place that Bach once held. Still holds, really.

Bahnson: You’ve written eloquently about the numinous, the beautiful, and what the Navajo call hózhó, a state of harmony. But you’ve also written about the human capacity for evil. In the January 2013 issue of Harper’s you had an essay called “Sliver of Sky,” which describes the years of sexual abuse you suffered as a child. When I read that, it seemed to offer a lens that helped me understand much of your previous work: the search for transcendence, anger over injustice and human cruelty, the search for places of purity as yet unsullied by human hands. What prompted you to write about this so late in life?

Lopez: There was no precipitating incident. Serial rape is a devastating, disorienting experience. It can take most of your life to put it behind you. When you’re trying to restructure your life, to not live with anger, and to be rid of feelings of impotence, it’s possible to arrive at a point of rest and to make a decision. I’d spent years dealing with this — upsetting memories, emotional disruption, always sensing some chaotic corner of darkness in me that was constantly present — and I thought, I need to be done with this. I’m capable as a writer of writing in an objective way about a subject, and I wanted to write this out and have it behind me. I no longer wanted to be structuring new challenges in my life in terms of that aspect of my childhood.

Bahnson: Was writing it a form of therapy?

Lopez: No.

Bahnson: You’d done the therapeutic work already, four years of it, so the writing was more reporting than processing?

Lopez: Yes. I hope I wrote the piece with as much objectivity as I wrote the polar-bear chapter in Arctic Dreams, for example. I was well-informed about pedophilic behavior. This was my experience with it, and I’m asking you as a reader, “What do you think?” The gesture that I wanted to emphasize at the end of that essay was my grandson’s taking my hand to cross the street. There was no more dependable person in the world for him in that particular moment to get him safely to the other side than me. I guess I was saying to the reader, “Be watchful. Watch over your children.” It’s something I wanted to . . . I’ll never be done with this, you know, but I wanted to be finished with it as a writer. It had always been hovering there, like tornado weather.

When the essay came out, I got lots of mail. I had to say to some, “I’m not a therapist. I can’t really help you.” Or, “No, I’m not willing to testify as an expert witness,” as several attorneys asked me to do. There were other letters saying, “Please join us in support of this law proposed in Congress.” I had to respond, “I’m a writer. I did the best I could with this material. If you want to use it, please use it. But I have to move on to something else.” It’s like many other things that I care about — wolves, for example. I’m not actively seeking practical solutions to game-management problems. That’s not my job. My job is to create clarity around complex issues, and to hand it to other people who are smarter than I am, and more strategic, who know how to draw up and implement effective laws. I know what I’m not any good at.

Bahnson: You put an incredibly difficult experience into language, and that was your service to others who had experienced a wound. It may not have been the wound you experienced, but they could see their experience in yours.

Lopez: Yes. That’s what I read in many of these letters. Sometimes when I speak in an auditorium, I’ll see a man, see the body language, and I’ll know: he read that essay and was then able to address his own history with some measure of hope. It’s unmistakable, the look in the face of a man who has been traumatized and then for years has felt isolated. It’s a simple thing to embrace these men or make eye contact with them — to minister, I guess you could say, to their need. Then you step on the stage and do your talk.

If you ask anyone walking down a sidewalk somewhere, “What is it that you really want?” I think many would say, “Intimacy. That’s the thing I don’t have in my life that I desperately need.” Lack of intimacy seems to cover a lot of the trouble we’re in. You can’t gain intimacy without vulnerability, and you can’t have vulnerability without trust. Part of our difficulty is that we have trouble trusting people, so we rarely get to the place where we can open up, become vulnerable. And until we get to that place, there is no intimacy for us, no emotional connection where we feel truly welcome and in which we’re able to participate fully. There’s a wall there we can’t get through. I think this wall is very familiar to many of us. We know the story well. So if you’re given the opportunity to write, I think you’ve got to address some of these things. It’s a part of your social responsibility.

Bahnson: There seems to be an obvious parallel here with our lack of intimacy with the land.

Lopez: Absolutely.

Bahnson: We’re not only severed from authentic, vulnerable, trusting human relationships, a severance that within human culture gives rise to the kind of abuse you described — the abuser himself was often abused or had some rupture of intimacy as a child—

Lopez: Yes.

Bahnson: —but that lack of intimacy and vulnerability in human culture is manifesting in a lack of intimacy with the land. Those two feed each other.

Lopez: I think they do. Something that affected me strongly in those years of abuse, and that saved me, was my experience with the natural world. I felt safe in those situations. They were the only thing that calmed me, that made me feel I was going to get through this somehow and be all right.

Bahnson: Your encounters with nature aren’t always benign. You write in Horizon about entering a dark wood at Cape Foulweather in Oregon and having a premonition of evil. Or in Tasmania, at Port Arthur, you visit the historic site of a former prison and describe touching a yellow Volvo and having a strong sense of evil. [The vehicle was owned by a man who would in a few weeks commit mass murder at the site. — Ed.] You’ve written in different ways about darkness. Do you seek it out?

Lopez: I think occasionally I do seek it out. When I was lying there on the hood of my truck at Cape Foulweather, reading a research paper, and I turned sideways and observed that little wood I’d seen fifty times, I suddenly saw something different. I knew how dense the spruce was in there. When you look from the outside, it doesn’t seem like there’s any light inside that forest. None. In that moment I felt I had to go find out what that darkness was about. I was a hundred feet into that wood before I began to feel uncomfortable. I turned around to look out to where the adjacent, brightly lit clear-cut was. I think I wrote that it was like looking at the sun through a colander, a thousand little pieces of light. After a while my eyes adjusted completely, and I got control of my racing heart.

I do want to find out what’s there in that darkness. There’s a line in Arctic Dreams about making of your life a “leaning into the light.” You have a choice. You’re never going to eliminate darkness, but you can lean into the light. I believe, though, you also need occasionally to lean into the darkness. I think a similar thing is in play when I talk in Horizon about the talismanic objects around my home: animal skulls, empty bird nests, aboriginal hunting implements, etc. I want not to forget these things. We also live in a world of death and must acknowledge it. The emotional darkness in some human lives is almost unbearable, so you have to find a way as a writer to let the readers see the light they know is there but which they can’t find.

What you asked me about is so intriguing. I remember one time, doing the research for Arctic Dreams, I was staying in a remote place very far north. Middle of winter. Total darkness. Thirty degrees below zero. This was on the sea ice at a drill rig called Cape Mamen. I was standing there next to an ATCO trailer, a prefab building like a mobile home. If I walked away from there, out over the frozen ocean, I thought, if I just hooked my foot under one of these cables leading to a positioning device out there in the ice fog, I could walk away safely into the dark. Away from the drill rig and the ATCO trailers, I’d only be able to see that cable over my boot, disappearing into a void in both directions. So I did. Maybe I was trying to remind myself that away from the known and expected world is where you find the threshold of your panic.

Bahnson: It seems that if you focus too much on beauty and light, that if you don’t acknowledge the shadow side, you’re not telling the whole story.

Lopez: Right. Or living the whole story. Do you think that the early Desert Fathers [third-century CE desert ascetics] were living the whole story?

Bahnson: Those guys took the whole asceticism thing too far, especially Saint Anthony, who walled himself in a cave for twenty years to wrestle with the demons, then came out in perfect peace. But there’s something to be said for going into struggle with the shadows.

Lopez: When he did that, who was Anthony’s community? It’s an immature notion, believing you’re going to deliberately suffer and die alone for something. How does the community benefit from this? The braver thing is to believe you’re going to live for something, despite the suffering. What Oren Lyons [a Native American elder and mentor to Lopez] said to me once was “Live for your people, but also understand that you will be forgotten. That you will die out there in anonymity.” That tells you something about community.

I get very uncomfortable around white people who want to be Indians. It’s like being around people who are always striving to make themselves seem interesting. What I wanted, when I was with traditional people, traveling with them, was to have their level of integration with the surrounding countryside, a topic I explore in Horizon. They were traveling without judgments; they were participating, silently, in the country we were walking through.

One night in a river valley in the Brooks Range in northern Alaska, a friend of mine saw something emblematic of this kind of intimacy: It was a cold night in the fall. A small group of people were out walking around through these enormous mountains and stopped to make tea. They built a small fire out of dwarf willows, little sticks, and were warming up around the fire, hunched up in their parkas. Suddenly there was a porcupine — startling to behold if you didn’t know porcupines lived around there, with no trees to climb. One man took his walking stick and like this [makes a welcoming motion] signaled, “Come on in. Get warm by the fire.” His attitude was that we’re all in this life together, sharing. It was an exciting “teachable moment,” as they say.

Bahnson: You write at the end of Horizon that “mystery is the real condition in which we live, not certainty.” The acceptance of mystery is one of the big themes of Horizon — really, of all your work. Other themes are empathy; the need to know the Other, both human and nonhuman; the place of memory in our lives; and the centrality of community, why it holds together and why it falls apart.

Lopez: Well, yes, those generally are my themes. Yesterday we were talking about [journalist and novelist] Eduardo Galeano’s idea of the writer as the “servant of memory.” What you remember personally, and what your people or your community remembers, are crucial to your own sense of self as a writer. The ability to give language to pain or injury or injustice, for example, is of great help to those who are unable to sort this out on their own. It’s interesting if the writer is a smart person, but this isn’t necessary. The one skill a writer must have is the ability to make meaningful patterns, in the same way a dancer or choreographer or a composer makes patterns. You make patterns, and they prompt an emotional or intellectual response. You achieve a level of clarity as a reader that you hadn’t been able to achieve before. The idea that the writer is a wise person . . . I tend to shrug my shoulders about that. A writer’s responsibility isn’t to be wise. There are wisdom keepers in all societies, and they aren’t necessarily storytellers. The storyteller’s responsibility is to remember what we are all prone to forget, and to say it memorably. In our culture we honor “progress.” In traditional cultures what they pay attention to is stability. I think we are now coming into a time when ensuring stability is more important than achieving progress. The only kind of progress I am interested in is greater social justice, the discovery and maintenance of socially just societies. Life punishes innocent people to such a degree that you can’t sleep at night thinking about it. Can’t we please make some progress here? That would help us more than another tweak of the iPhone’s capability. I wish we were paying as much attention as a country to unstable social organization as we’re paying to the so-called promise of artificial intelligence.

Bahnson: I want to move on to your visit to Port Arthur, the site of a former British prison in Tasmania, where rampant sexual abuse of child prisoners occurred in the late 1800s. Some of the young boys, seeing no way out of the abuse and violence they suffered, committed suicide by jumping off a nearby cliff into the sea. Was your visit there a way of confronting your own abuse? What did you find at Port Arthur, and what were you trying to understand?

Lopez: I didn’t want to go to Port Arthur just to bear witness in a place of brutality, or to reengage, either, with the horror of my childhood. It’s not in my nature, you know, to be a bold adventurer, a guy leading everyone else on a climb. I’m the second person on the climb, supporting the leader and making sure everybody behind me gets to the top. I have to go into challenging situations — like what happened at Port Arthur — in order to understand better what every one of us has had to face, in one form or another. I once went out on the deck of a ship in a Beaufort force 11 storm in the Southern Ocean. One mistake out there and you’re gone. (A force 12 storm is a hurricane.) I wanted to feel it. I once spent several weeks diving under the ice in Antarctica. It’s dangerous, that kind of diving, in part because of equipment failure and because there’s no way out if something goes wrong except the hole in the ice through which you entered. I don’t think of these endeavors as brave or heroic. I need to do these things in order to understand what I’m writing about. I only go into these situations if I’m with people who are really good at what they do and who plan carefully and execute safely. Then, for me, once you sign on, the anxiety about the danger disappears. I have a high degree of self-confidence, and I don’t do foolish things. But I feel I need to do some things in order to understand the world and to write about it. I recognize bravado in other people, and, to the extent I can, I steer clear of it.

Bahnson: You talk a lot about punishment in the chapter of Horizon that starts with the Port Arthur scenes. How can we address this human urge we have to punish, to lock up, to throw away people we don’t want? Look at the mass incarceration in our country. Do you think something like South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation project would work here?

Lopez: No, I don’t. I’ve talked with Archbishop Desmond Tutu at length about this. It worked pretty well in South Africa. It didn’t work well in Rwanda, and I don’t think it would work well in the United States as a way to deal with our polarization. We have to find some other route to achieve peace and justice. Those are the goals. Archbishop Tutu told me the mistake you can easily make — I write about this also in Horizon — is going after the one or the other. You can pursue justice exclusively and create social chaos, or you can pursue peace exclusively and let true barbarians go unpunished. You’ve got to find some middle ground between absolute peace and absolute justice.

The United States, like every other nation, is a country with a complicated moral history. It’s still saturated with antiquated, nineteenth-century ideas like the primacy of the nation-state, and it champions one of the most abusive systems of profiteering ever invented: capitalism. To achieve justice and peace in a country so thoroughly committed to the primacy of the nation-state and capitalism — that’s pretty tough. But I would add that you have to try. You have to try. It’s why Horizon ends the way it does. You go into that chapel at Port Famine in southern Chile, and you find the anguished hopes of ordinary people. If you’re in a position to help them, you must. All you need is the conviction that you are capable of offering help. It’s like when you’re climbing, and the strength to believe in the existence of the next handhold is given to you by the person below you, who does nothing but look at you with encouragement. The sense that you are in some formidable, challenging task together makes all the difference. You don’t have to talk to each other; you either know what is just, what is a move toward peace, or you don’t.

We are now coming into a time when ensuring stability is more important than achieving progress. The only kind of progress I am interested in is greater social justice.

Bahnson: “You nurture the belief that this is not all that we are,” you write.

Lopez: Yeah. Myself, I’ve got to get to a place where I can accept what Stalin did to people in the Siberian gulags, the scale of it. This, too, is us. This is what we do. That’s why I told my grandson in the book’s prologue, as we stood over the wreckage of that battleship at Pearl Harbor, “This is what we do.” He had no idea that we killed each other on that scale. But I could say to him, “I love you, and I want you to know that this is what we do. And as you grow, you will see a way to help. And I hope that when you do, you choose that path, no matter how hard it is.” And, I would add now, you can do that in a monastic cell or in the great wide open. I don’t think you can do it in government, and I know you can’t do it in corporate business. Everything large-scale business promotes is antithetical to the support of life. The major, fundamental contradiction in this country is that you can’t have a true democracy built around the goals capitalism espouses. You can’t do it. You’ve got to change it, and what a vision that is.

Bahnson: You’ve suggested that the figure of the culture hero — Prometheus or Siddhartha Gautama or Superman — is no longer relevant in the age of an exponentially expanding human population. The scale of the problem is beyond the lone hero. What stories should replace the story of the culture hero?

Lopez: They haven’t been written yet. When you read hero stories like the Epic of Gilgamesh, or the Odyssey, or the Aeneid, or any of the enshrined stories by which we define our culture in the West, you see it’s great literature, and that it’s deep and profound and true. But does it serve us now? I don’t think so. Too many people are standing around waiting for a hero to appear. And the idea that a woman or a man or a child will suddenly stand up and change everything seems naive now. The world is moving too quickly. There’s real trouble on every front: Governance. Social justice. Environment. Investment.

Bahnson: That’s a profound idea, that those stories we’ve relied on for so long aren’t working anymore. We need different narratives.

Lopez: We need new narratives at the center of which is a concern for the fate of all people. The story can’t be about the heroism of one person. It has to be about the heroism of communities. The mathematics here dictates that.

Bahnson: And yet we can’t hold in our minds something like “humanity.” It’s too large a concept. To have a story that places at the center the well-being of everyone seems to negate what a story does, which is to focus on the specifics of a character or group of characters.

Lopez: But story is merely a pattern that signifies. The blueprint for our story is before us all the time. Watch a flock of starlings. When you’re driving up an interstate in an agricultural landscape like California’s Central Valley, where there’s lots of sky, lots of space, you feel like you want to pull over and watch the display of coordination as a flock of starlings changes direction overhead. It’s important to consider that the starling is a pariah bird, an “ordinary avian,” not a golden eagle or a harlequin duck. The flock is carving open space up into the most complex geometrical volumes, and you have to ask yourself, How do they do that? The answer is: No one’s giving anyone else instructions. You look to the four or five birds immediately around you. You coordinate with them. The intricacy of that lattice means that one of the birds you’re using as a guide for your own maneuvering is itself watching the birds around it to coordinate its movement. There’s no leader, no driver. It is an aggregate of birds. To behold them is to take in something beautiful, a coordinated effort to do something in which there’s no leader, no hero. That’s to me the way around that dilemma of scale: a much greater level of coordination and deference toward others.

You must rid yourself of the idea that only one person knows, and understand that genius might be manifest in one man or one woman in a particular moment, but that the quality of genius that characterizes humanity is actually possessed by the community. It might rise up and become reified in a single person in a group, but it doesn’t belong solely to that person.

Bahnson: I love that idea of using bird behavior as an analogue for how to organize human communities. Clearly within a human flock we need people who can shift the group somehow, which is different from being a hero. I’m thinking here of your ideas about the importance of elders. You’ve said that two thoughts have organized your perceptions of nature for decades: biodiversity is crucial if life is to go on, and a community of wisdom keepers is crucial to keep society stable. What are the qualities that make for a good elder?

Lopez: With starlings moving over open country, whatever the goal is — if, indeed, they have a goal; it could be something innocuous, like having fun. But what’s modeled there is a way to get something done. The hallmark of a Western approach to dilemmas is to follow a leader. Somebody says, “This situation is really bad. Follow me. I know the way out.” We’re very familiar with that way of doing things. You don’t see that sort of thing, however, in traditional cultures. What you see is the working out of a very different idea, which is “Leave no one behind.” I think this is ingenious. You have to make decisions that are good for everybody. You don’t say, “For everybody except those without a high-school education,” or “those whose skin is dark,” or “whose philosophy of life is not mainstream.” In a traditional setting, elders would say, “Well, if the solution doesn’t help everyone, then we’re not going to go in that direction.” Providing for all ensures stability for all.

My thought now is, we’ve got to find a way to do that. I’m speaking here, I must say, right at the edge of my competence. I can understand things in the world, whether it’s the behavior of polar bears or the way light shifts during the day and changes the look of a landscape. I can find language that will bring those things to life in the mind of another person. But when it comes to — to put it too simply — the development of wise policy, I have no gift. That’s not my bailiwick. My job is to write a story, to place it before people and say the chances are that somebody way smarter than I am, or who has a better imagination than I do, is going to see something in this story that is invisible to me but to them is the key to policy development that will get us somewhere safe.

Bahnson: So, again, what are the qualities that make for a good elder?

Lopez: First, there’s not just one elder in a group. Elders operate by counseling with other elders. It’s not the “follow me” kind of thing. But most of these people do have shared characteristics: They are great listeners. They can talk for hours without ever using the word I. They take life more seriously than most of us. They are able to relate to children as human beings and not as people that need to be taught something or corrected. The job of the elder, where children are concerned, is to make them feel welcome in the group and safe. Elders also tend to be invisible in a village. With every village I’ve visited, I’ve wanted to listen to elders speak, because they’re the warehouses of knowledge. They understand what will work and what won’t work. They’re adept at addressing a dynamic of which a particular event is only one part. They can see quickly where things have gone wrong. They are the great historians of what will work. So I want to see them, like anybody would, because they’ve condensed human experience. You can learn a lot by just listening to them.

Bahnson: I’m guessing that the kind of elders you’re talking about are people most of us have never heard of.

Lopez: Or seen. They don’t seek to be known. If you enter a village and say you want to speak with the elders, you’re going to have to wait awhile to make those kinds of contacts. If you demonstrate that you’re a grown-up — by that I mean you’ve shown, for example, that you’re interested in and respectful of children as well as adults — you might be invited to visit with the people you want to meet. I’m wary of categorizing traditional people and putting them all in one box, but these characterizations of an elder do seem to hold across the board. I think what has happened in our society, and in other Western societies, is that the elders were telling us things we didn’t want to hear, so we’ve gotten rid of them. A lot of their message for us was “You’ve got to grow up. You’re too distracted by venal desires, and you are ignoring your responsibilities to others.” What we’ve said to elders in the West is “Oh, shut up.” We’ve pushed them off into the darkness, denied them a place of respect.

You look like you’ve got something on your mind?

Bahnson: You say that our culture’s rejection of elders is because we are afraid they might tell us a story we don’t want to hear, and that makes me want to ask you about story. We’re prone to thinking of stories as entertainment or diversion, but you see something different in them. What is the purpose of a story? How can stories bring healing?

Lopez: There are some stories that we love to hear because they entertain us. They make us laugh. They create conviviality. They encourage good fellowship. Those are what you might call maintenance stories, like the three meals a day we look for. The stories I’m trying to write and which I want to promote are stories that contribute to the stability of my own culture; stories that elevate, that keep things from flying apart. I want us to do well. I recognize that Homo sapiens is one animal that has spread across the earth and killed many other species because it wanted what they had.

There are many reasons to tell stories: shaggy-dog stories, instructive Aesopian stories, detective stories, scary stories, reminiscences of all sorts. I honor them all, and have tried my hand at all of them and mostly failed. My particular reason for writing is to provide illumination for a nation that is chronically, pathologically distracted. I hope that in the right hands, other people will regard the stories as templates useful in shaping a different world. They will recognize, for example, the wisdom in stability.

Bahnson: That’s a very monastic thing to say, the “wisdom in stability.”

Lopez: The Desert Fathers and the monastic tradition generally, for me, are not about religion; they’re about the numinous. About leading a spiritual life. We’ve found it useful to strip spirituality out of our culture, because spirituality gets in the way. It urges us to be moral, to be ethical. It urges us to be compassionate. These are things that many people find inconvenient. I’ve been aware all my adult life of monastic wisdom, and the widespread idea in Judaism that there are thirty-six good people, the Tzadikim Nistarim, whose prayer, whose daily prayer, revolves around the love of something beyond the self. I’m always looking for that kind of commitment. And I believe, too, that this kind of love is also to be found outside the human world, not just within it. To dismiss contemplative life as a luxury or as an idiotic thing to be doing in 2019 is to misunderstand the whole tradition of monasticism, which is known by different names in different cultures. But that idea — a handful of just people who are unaware of each other but who continue their prayerful way in the world — is to be found among many cultures. Those people are the ones, many believe, who provide humanity with stability. Indigenous people call these people “the elders.” The thing to value here is not progress; it’s stability in the storm. Who provides stability in the chaos of modern life? It is people living in a prayerful way. And living in a prayerful way doesn’t need to have a formal religious structure around it.

I’m a little hesitant to talk about this, because we’re so quick to take too many stories literally instead of metaphorically, and because we’re bombarded by so many stories every day we tend to dismiss some of them too quickly. A reader might say, “Oh, they’re talking about monasteries. I don’t have any interest in monasteries.” A culture like ours, poorly trained in metaphorical expression and presentation, completely misunderstands most traditional stories. We also have a large number of people who are very difficult to communicate with, because they’ve given themselves over entirely to the rational mind. They are literal to the point of neurosis.

Bahnson: Is that capacity for metaphor innate, or is it learned?

Lopez: I think in traditional cultures the ability is inculcated to such a degree that they don’t even recognize they have it.

Bahnson: How can we reclaim that metaphorical way of thinking in our culture?

Lopez: A very long shower. The amount of stuff we have to get rid of to achieve stability in our daily lives is enormous. Storks, you know, migrate in long lines that are horizontal and perpendicular to the direction of their flight. They glide instead of flapping to maintain altitude, and as they slowly lose altitude, they all look up and down the line for someone who’s found a thermal and begun to rise to a higher altitude in it. Then they all go to that place, rise up in the thermal that that one bird found, and then they spread out again; and again they slowly lose altitude until some other bird finds the next thermal, several miles on, and then they all go up again. It’s not one individual who ensures a successful migration. Maintaining direction is something the community does.

In order for a human community to remain stable, to not break down — I’m going on to another idea here — it must have a council of elders. You go to the elders when you have an unstable situation in your life: a falling-out with your parents, say. You go and talk to an elder about it. You’re really worried, or maybe you’re terrified, and the elder might say, “Oh, that’s nothing to worry about.” And you might say, “What? This is eating me up!” But the elder sees the larger picture. The most important thing for the elder to do in these situations is to put the other person at ease. On the other hand, you might casually mention something you’re doing and then hear the elder say, “You’ve really got to be careful with that one.” You’ll think, What? But the elder sees what you are missing. In a culture that understands that the repository of its wisdom lies with a group of elders, fewer people lose their way. The elders ensure the stability of the community, which means the community can face danger more successfully, with more confidence.

This is the only form of social organization, I think, that’s ever really worked for people. Elders. For a while democracy has been a good idea, but it’s clearly not a good idea now. A major question for us in the West is what comes after democracy, and how do we achieve that? To go back to your earlier question, asking Archbishop Tutu exactly what they were doing by developing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, that would be a good conversation to have. Democracy is no longer working here. It’s been infiltrated by people with commercial goals, and the level of corruption and corrupt intention is now staggering.

I’m talking to you as if I know something about governance, and I don’t. All I know is how to write. But these traditional values of community organization go back fifty thousand years with some aboriginal people. To assume that their ways are inferior, or that they no longer apply, seems unenlightened.

Bahnson: You preempted one of my questions about indigenous peoples you’ve moved among. An important metaphor for you is the isumataq, the Inuktitut word for storyteller: “a person who creates the atmosphere in which wisdom reveals itself.” Many believe we are facing a cultural failure of European ways of thinking and being in the world. How might indigenous voices help us reclaim our humanity?

Lopez: Just ask them. Ask them to come to the table. They’re so rarely asked. Even though indigenous people have been brutally punished and made the victims of genocide, they are still willing to help. This is a miracle! You just need to ask. And you must direct your attention to the adults among them. And let the adults among them choose who will go to the table. If you insist on picking the people yourself who are to be heard, you’ll end up with children — people with agendas and those who are eager to impress, inclined toward self-righteousness and pettiness, or on a quest for control.

Bahnson: We’re suffering under the presidency of a child right now.

Lopez: I agree. When I say an “adult,” I mean a person who no longer needs to be supervised. A person who knows what to do to ensure the ongoing vitality of the community. You don’t have to worry about adults going off on their own and starting to build empires or something like that. One of the most refreshing experiences of being among traditional people for me is to feel the level of maturity in conversations with their elders. Elders take into consideration how “old” you are, meaning what is your life experience and what have you done with it. You get the feeling that you’re being heard. People know that if their elders weren’t hard on them, they wouldn’t be around now. Your people would have been eclipsed. The reason you’re still here is because these elders have consistently made the right decision. There are moments when everybody starves. That’s life. But to remain a coherent, stable culture for hundreds and thousands — or, in the case of Aboriginals in Australia, tens of thousands — of years means that the right people, the elders, have consistently been making the right decisions.

Bahnson: What you’re saying about the need for adults makes me think about climate change. Clearly our leaders have not been acting like adults. You’ve written, “However it might be viewed, the throttled Earth — the scalped, the mined, the industrially farmed, the drilled, polluted, and suctioned land, endlessly manipulated for further development and profit — is now our home. We know the wounds. We have come to accept them. And we ask, many of us, What will the next step be?” Global climate change is the biggest threat on the horizon — except it’s not on the horizon; it’s already arrived. You’ve seen the effects in the polar regions and even right here on the McKenzie River.

Lopez: Yup. Parts of the Arctic Ocean I knew as ice-covered in the summer more than forty years ago are now areas of open water for thousands of square miles. And here on the McKenzie I’m watching trees in this temperate rain forest dying of drought.

The creative effort of the imagination is to turn the boundary into a horizon. Then it’s possible to say, “Let’s go there, and there, and there,” because there’s no end point for you.

Bahnson: How will we evolve in the face of this? How will we confront it? You’ve said it’s going to take an unprecedented level of imagination to confront this, so perhaps you can start with imagination?

Lopez: Many of us feel we’re stuck with a dead-end street because of global climate change. That’s why Roy Scranton was able to write a book with the title Learning to Die in the Anthropocene, because people are now familiar with despair on this scale, believing we’re at some sort of terminal point. Whether or not we are, I don’t know.

Something I learned from scuba diving is that if you’re a terrestrial creature, a landscape changes from side to side as you swivel your head. If you’re diving, that happens, too, but it also changes vertically. You can be looking horizontally when you’re at 150 feet or at 30 feet, but then you add that vertical component. If I can stretch this comparison a bit: When you arrive in a box canyon, what you’re actually looking at is a box without a lid. You can’t get out of there the way a bird can. If you enter a box canyon as a diver, however, you just rise up in the water column and swim on. So part of what I was trying to do in Horizon is to encourage people to imagine the world on axes different from the ones that function like boundaries for us instead of horizons. A boundary says, “Here and no further.” A horizon says, “Welcome.” You know you can go on from there.

[The eighteenth-century British explorer] James Cook, of course, used a grid of lines — latitude and longitude — that made profitable international trade possible. We can see what that has engendered. Missing from the latitude-and-longitude grid is any third dimension. It doesn’t extend into the sky or go below the surface of the earth, and it has no temporal component. It’s a timeless grid. The awareness of that creates the impression that we have limits when we don’t. Our certainty about the accuracy of latitude and longitude as a locator can become a trap for us. If you stay in this place out of fear, you will not find the landscape that your imagination is yearning for. If somebody says to you some of the proposals I’m making — that we’ve got to find another way, that we can’t keep doing this — are not possible, it’s because they’re trapped within those boundaries. The creative effort of the imagination is to turn the boundary into a horizon. Then it’s possible to say, “Let’s go there, and there, and there,” because there’s no end point for you, especially not on the surface of a sphere, the globe. Throughout Horizon I’m talking about establishing another geography.

Bahnson: A moral geography?

Lopez: Yes, partly. That’s a term the Australian writer Mark Tredinnick uses. I’m actually uncomfortable with that locution, but I don’t know what the alternative is. Some new sort of geography will drive policy. There are rubrics for behavior, you know, and we’re operating today with some really worn-out rubrics that originate in medieval European thinking. They’re not helping us here. We need another way of knowing. But it can’t be another way of knowing created by the chaos in democratic societies.

One interesting thing about elders is that you don’t know who they are right away. They don’t stand out. If I went into a village, it would often be a while before they became apparent to me and I was introduced to them; but there’s no question about their being the decision makers. So part of the genius of aboriginal communities is, if everybody knows who the really smart people are, they’re going to let those people make all the decisions as long as they — the people who are granting unilateral leadership to these elders — as long as they themselves and their suggestions are treated with respect. Many traditional societies are organized that way. When something bad happens, you think, These guys are going to take care of it. And you say to them, “What do you want me to do?” You don’t say, “Hey, I have an idea!” Your idea is probably not going to help. When the Titanic hit the iceberg, they didn’t get everybody together to talk over each person’s ideas about what to do. They got the engineer and the captain, the people who were in a position to know where the bulkheads were likely to fail, for example. We’re in the same situation now. In contemporary America we often assert that every individual has a right to be heard. Well, maybe they have a right to be heard, but we all know that some people don’t have much to say. It is the immaturity of democracy that comes through at that point. If you are making room for everybody who wants their voice to be heard in an emergency, you haven’t been paying attention to the history of Homo sapiens. In traditional societies no one feels disregarded if elders make decisions. If the elders show respect for everybody, make them feel indispensable in the process, then when something really bad happens, the community will say to the elders, “What do you want me to do?” and not feel ignored or diminished. In traditional societies it is assumed that elders will make decisions that leave nobody behind, instead of the opposite — the way we do it. We tend to choose unelected, self-promoting, charismatic people who just turn up on the scene, and then we blindly follow their advice.

I was in a meeting that the Rockefeller brothers organized some years ago. A group of us got together to talk about what kind of crap has hit the fan and what are we going to do, and [writer] Rebecca Solnit made a succinct observation: that we in the West are preparing to defend ourselves against threats that have already arrived, that are already embedded within our culture.

So the idea that the enemy is out there somewhere and we’re going to build impregnable defenses is lunatic. The enemy is already here. When it comes to global climate change or ocean acidification or methane gas shooting skyward out of melting permafrost, that stuff is already here. Setting goals for reducing CO2 by 2030 . . . [Shakes his head.] I don’t think so. I mean, you do those kinds of things because you want to demonstrate that you are being responsible. But you have completely irresponsible people in control of government, the same people who are today in control of big business. They’re not all bad people, but they’re playing a dangerous game thinking they can get out of here with a large bank account intact, and believing they aren’t going to still be around when it really gets miserable. This attitude reveals a fundamental lack of charity. You’re telling me you have to get more, and whatever happens to your children, that’s just a shoulder shrug? Or do you have a sense of charity that says everybody — everybody — has to be taken care of? No “This guy is black,” or “She’s a lesbian,” or “This guy is not an American.” That’s immoral. That kind of conversation needs to end. But of course it won’t. Look what just happened in Georgia and Florida [referring to the 2018 midterm elections]: “Let’s get these people off the voting rolls. Then the world will be better.” It’s ignorant and immoral.

Bahnson: Earlier you mentioned prayer and ceremony. Tell me who God is for you.

Lopez: That. [Gestures to the trees outside the window and the river beyond.] Everything outside the self. Outside the realm of “I am important”; “I” this, “I” that. The essence of the Divine is good relations across the board. You have the opportunity as an individual to create good relations wherever you go. And when relations are perfect, that’s the physicists’ singularity. That seems a metaphorically accurate definition of the Divine, where everything that is present is necessary, nothing unnecessary is here, and there are no seams. It can’t be parsed, can’t be dismantled. It is perfect integration.

In our lives most of us have a longing to be included. In many Western traditions when you pray, what you are saying to God is “Include me. I want to be included.” Your life becomes seeing how to be worthy of inclusion and how to include others.

You know, I had a Roman Catholic education. I never developed any antipathy for the Church, though most of my friends did. They were sometimes irate. They felt tricked. Duped. When I went to Notre Dame [as an undergraduate], I went to Mass three times a week in the dormitory chapel. In New York City, as an adolescent, I was in these little groups of five altar boys who went around to different churches in Manhattan to serve at High Mass because we knew all the performance detail for celebrating Easter High Mass at midnight, for example. We had all that stuff down tight. If the priest lost his way in the liturgy, we could quietly steer him back on course. We knew which pieces of incense were to be placed where in the paschal candle. We were locked in to all the details of the ceremony.

I began to drift away from all that in my late teens, but not in anger. It was time for me to go. Time for me to get out of that comfortable place where all my classmates were white, Catholic, male, and middle-class. I thought, I’ve got to back out of here and find the fuller thing. Once, I was playing baseball. I had my senior ring on. You know how you don’t want the pitcher to push you off the plate? He threw an inside pitch, and instead of stepping back, I just pulled my hands and the bat in tight to my chest. The ball hit my ring and shattered the stone. Instead of getting a new stone right away, I thought, I believe there is something missing in this very good education of mine, and I need to find out what it is. So I left the ring empty for the next three years. There was something I couldn’t define about my education that made it feel incomplete. That soon led to coming back out west, where I grew up. I came to Oregon to get an MFA, though I quickly saw that the program was not much good — for me. I did meet some people there at the university who became very important for me — Barre Toelken [in the English department] was one of them. If there were any people of color or Native Americans or Asians in that very white town, they always turned up at the Toelken house for dinner. I thought, Yeah, this is more what I was looking for.

Bahnson: You’d found your people.

Lopez: Yeah. And a greater awareness that the Roman Catholic experience I’d had was bounded. (Christ, of course, was not.) What was I going to do about that? I’m still working my way through this. I don’t want to throw away half a lifetime of understanding the Divine in terms that I was comfortable with. I’m reminded of a short story I wrote called “The Letters of Heaven.” [It appears in the Fall 1997 issue of The Georgia Review. — Ed.] Historical fiction. Martín de Porres and Rosa de Lima, in that story, were more than seventeenth-century Catholic saints. They were two people participating in the ecstatic experience of the Divine in all they did. I was attracted to that. My understanding of God at that time was “Look elsewhere. Look for manifestations of the Divine that occur outside your reference points.” The sign of the Divine for me was any experience of profound love. If you experience that, it’s a sign of the presence of God. I still think that way. If somebody is on the paths called Hindu or Catholic or Jewish and moving toward that depth of love, I’m thrilled to see it. I was in Lebanon once, in Beirut. I asked a man if I could go to “ceremony” with him. For the first time I went to a mosque. I felt filled with love there. I felt companionship toward all the people I was with. I felt the presence of the Divine because of the serious and humble effort at prayer: to forget all the intrusions, the distractions, and concentrate on the Divine. I thought to myself, I want to be here. It’s incidental that it was a mosque.

I wish I knew better how to communicate with people who say, “You’ve lost your faith.” I have not lost my faith. My faith has grown. [Laughs.] You know, when I say “adults” and think of what Aboriginal and Native American and Eskimo people have taught me about what it means to be a grown-up, I want that transitional experience to occur for everyone. Things like nationalism or fanatic devotion to a particular interpretation of a sacred text bring nothing but pain and criminal behavior: murder, slander, ethnic war. If only we could just exist on this plane where everybody understood that the Divine is incomprehensible but sometimes apparent. And when it is apparent, it deserves your full attention. If you’re really advanced, you know you’re in the presence of the Divine even when you’re doing the dishes. So my answer to the trouble is: Make your acquaintance with God, in whatever form that takes for you. It’s just good relations with the Divine that gets you through the wickedest trouble.

Bahnson: A number of people are now saying that our ecological crisis is at root a spiritual crisis. What are your thoughts on that?

Lopez: Well, the trouble is biological, too. Fundamentally. And if you wish to address our ecological crisis by hitting the brakes in your life, you need to begin with biology. Heathen behavior, spiritual erosion — that seems a tougher nut to crack.

Bahnson: But what got us here?

Lopez: Sacrilege. We’ve awakened to a world created by our being sacrilegious.

Bahnson: By not seeing the world as sacred?

Lopez: Yes. By not understanding the sacred. You know, it’s up to atmospheric chemists to tell us whether climate change is reversible. It’s my understanding that it’s not. So then the question becomes something like “What is a beautiful death?” I sometimes wonder what would happen if Cougar Dam [upriver from his home on the McKenzie River] collapsed and a biblical flood came down this narrow corridor. The right thing to do would be to comfort your neighbors and accept their offer of comfort. I think most of our anxiety, at a certain level, is driven by rampant speculation. It’s possible, though, to choose to die in a good way. I think it was Ignatius of Loyola who, when someone asked him, “If you knew with an hour’s warning that your death was coming, what would you do?” said, “Exactly what I’m doing now.” You can’t make special arrangements because your death is imminent. You need to continue to lead the life you are leading, to maintain your integrity.

I have thought a lot about intentionality with regard to what people in some traditions call “sin” or “transgression.” I remember clearly one night in 1969 when I was in Eugene, [Oregon,] where I was a graduate student at the university. I was walking one night around a familiar corner where ivy was growing on a curving brick wall. I stared at this in the darkness, trying to make out the pattern. It was this rambling, ramulose design, but when I looked more carefully at it, I thought, Oh, the ivy is continuously seeking the light. It goes up and down, left and right. It is the intention of the vine to find sunlight. It adheres to the wall so it can get up higher. The fact that it goes left or right — that’s not a “sin.” It’s evidence of its intentionality. It seemed a way to understand that, with all moral transgressions, there is a process. To have done something you knew was wrong, then made the effort to understand what it was and to correct your behavior, is all part of the same movement — to get to the light. And so to condemn yourself unduly or to condemn others is to misunderstand that dynamic. What is the nature of the yearning? It is to be united with the Divine. Everybody goes down. We know everybody goes down. Fails.

Bahnson: Mortality rate is right at 100 percent.

Lopez: Exactly.

Bahnson: You were speaking about what makes for a beautiful death. You’re confronting a metastatic-cancer diagnosis. You’ve said you don’t like the metaphor of “fighting” or “beating” cancer.

Lopez: No, I don’t like the military metaphors. I say I’m doing the best I can in the circumstances. My body has changed radically in the last five and a half years — sixty-seven months since the diagnosis. There’s no elasticity anymore in my skin. When I take my socks off at night, the band of compressed flesh around my ankle remains there for hours. I’ve lost my capacity to thermoregulate properly. I’m always cold or hot, I’m always taking my clothes off or putting them on. The male parts of my body have shrunk. I’ve little sexual awareness or drive. [Chuckles.] OK, who needs this list? I have a diminished sense of balance. I’m constantly stumbling and banging into door frames. I can enumerate those things, but I really don’t pay too much attention to them. The driving thought is always, Do as well as you can for as long as you can. And then, like everyone else, you will be gone.

I recently had a discussion with the writer David Quammen, a close friend, and asked him, after a life of travel, whether I should now stay at home, maybe finish a few books that I’ve begun, or should I be back out on the road one more time, researching a new book? Given my physical ailments, maybe my life would end out there on the road. He’s a heavy traveler. He said if he was flying in a plane over the jungle somewhere in Africa, working on a story, and the plane went down, he’d be OK with that. I had a similar conversation with another friend, a National Geographic photographer. If you’re in a Land Rover photographing lions, they don’t register you, certainly not as prey. But if you get out of that Land Rover and you close the door — boom. They lock on to you in a different way. So, if the idea is to create images that convey the nature of the animals’ ecological plight, and the only way to get those images is to get out of the vehicle, do you go ahead and do that, knowing someone will say this is bravado or that it’s a stupid thing to do? No, it isn’t. It’s an effort on the part of the photographer to get this message through: For the most part, leave life that is not yours alone. Leave it alone. He and I have had these discussions about what you did when you were far from your comfort zone and you risked your life. Was that stupid? No. The question has to be: What are you trading your life for? You’re trading it on the chance that what you’re doing will be understood in a more profound way. That somebody will understand from those images how clearly imperiled we are.

Bahnson: And yet not all journeys have to be physical. Can’t that journey into our imperiled state be made right here?

Lopez: Everything you need to know is in the cell. [Lopez is referring to the monastic cell and is paraphrasing one of the Desert Fathers. — Ed.] It’s a romance to think that the questing that I did in my thirties, forties, fifties, and sixties . . . I loved having my face in the wind. I loved the incidental and inevitable pain and inconvenience to get to the thing that was the object of the quest. I can’t do that now, and I’m trying to understand how I can create an alternative. Everything you need to know is right there in your cell. I’m just a little reluctant to shut down the travel. I want to be out there. Years ago I would sit at my desk, look out at the river, and think, You know, the only thing difficult about living here in the woods is that I can’t regularly stand outside in open sunshine. In just a few moments I’ll be back in the shadows of the trees as the Earth rotates. And at night I have to watch the stars through all of these limbs. Then it dawned on me that if I was out there on the river, I wouldn’t have those problems. I could look up at the stars or stand in the sunshine, and there’d be nothing in the way. So one day I did that. I waded out to the rocks midstream and did my work out there. I put on my wet suit and wandered upstream and then downstream for hours, like a hiker. It was a reimagining of the open space above the river.

That experience was one of the things that taught me, given the environmental situation we’re living in now, that “this is something that has to be dreamed again,” as an indigenous person might say. You’ve got to reconsider the organization of the physical world and your place in it in order to find the new orientation you need, if you’re not to be done in by the forces all around you. The sunshine I craved was actually available. It was out there over the river. I could sit there in direct sunlight for hours and work. Kayakers passing by and seeing me a hundred feet from the riverbank would shout, “Hey, are you all right? Did you fall out of a boat?” [Chuckles.] “No, I’m all right.” I was just using this familiar space in a different way.

I was flying back once from Barrow, the northernmost point in Alaska, flying back to Fairbanks. It was midwinter, so it was dark all day. I had a window seat in an empty row. I was looking out over the tundra below, lit up by moonlight, and then I glanced up where the window cut off the upper part of the sky. The Northern Lights were flashing there, but I couldn’t see them very well from where I sat. So I piled all my carry-on gear where my feet had been, rotated 180 degrees in my seat so that my legs ran up the back of the seat and my butt was in the seat crease. My back was supported by the seat cushion, and my head rested on the pile of luggage on the floor. I was now looking out the window at the Northern Lights above the plane, not down at the tundra, and thinking, It’s so easy in your life not to do this, because it’s not what people do, and then you miss that. [Laughs.] You miss the Northern Lights because you were afraid of looking like an idiot upside down in your seat.

Once, in Australia, I took the Indian Pacific train across the whole country, from Sydney to Perth. When I began in Sydney, I asked the engineers if I could ride up front in the locomotive with them. (The porter had told me he thought it was not permitted, but urged me to ask the engineers.) They said, “Sure. Come on up.” Several days later we were crossing the Nullarbor Plain when this huge, ferocious rainstorm came blowing through from the southwest. The sky off to our left gave birth to a rainbow. Hundreds of kangaroos were thundering across the land beneath that sky. In the cab the two engineers and I nodded to each other wordlessly. Whatever magic was in the world, we were in it together now. We shook hands.

Whenever you can, I believe it’s good to make yourself available for these events. To try to reimagine the world.