The summer after my fourth-grade year, the circus came to our small suburban town. Two weeks before the tents rolled in, the local Kiwanis Club, of which my dad was president, sponsored a contest. Coloring-book pictures of clown faces were distributed at the supermarket, and the kid who colored the best clown face would be named Honorary Ringmaster and would get to wear a top hat and blow the whistle to begin the circus.

I wanted desperately to win. For a week I worked on my clown face. No magic markers or crayons for me. I used oil pastels, smearing the colors together with Vaseline. Then I painstakingly inked the background with a black Sharpie and boosted the white of the clown face with coats of white-out. Surrounded by the other kids’ Crayola submissions, my clown gleamed from the bulletin board at the supermarket. There was no competition.

The night before the circus arrived, my dad gently broke the news: he’d been reminded that his position as Kiwanis Club president automatically disqualified me from the contest. Everyone agreed my clown was the best, he said, “but it wouldn’t look right if you won. Understand?”

I did not. I sobbed myself to sleep.

At 4 AM the next morning there was a knock at my bedroom door. My father handed me one of his old flannel shirts to pull on over my pajamas, and then we drove to the circus grounds, where the painted trucks carrying tents, cannons, lions, and elephants were pulling onto the fields. He and I stood in the dewy grass in silence as the workers set up the tents, pitched hay for the animals, and erected giant billboards with grinning clown faces.

When the big top was finally up, Dad spoke to one of the workers, who lifted the canvas flap and led us into the sawdust-filled ring in the middle of the massive, empty tent. My dad stepped back and let me stand there alone for a moment. Then he put his arms around me and didn’t let go for a long time.

Kate Quarfordt

Brooklyn, New York

It wasn’t an easy decision to feed the feral silver-and-white cat. Prison cats live such short lives, too often ended by disease, cars, razor wire, and periodic trapping by the prison guards for euthanasia. As soon as you form an attachment, they’re gone. And she was just a tiny scrap of a cat, terrified of everyone and everything. But she looked so much like my last cat on the outside that I couldn’t help but tempt her to my cell window with a little food. I named her Violet.

It was stressful smuggling food from the chow hall and sneaking it past the pat searches, but I did it twice a day, every day. I had to ward off the cat haters and bullies in my dorm who just needed someplace to direct their anger. When I defended Violet from these women, I became more fearsome than I really am. I would have done anything to keep her from harm. I watched her belly grow round with kittens, then worried over every scratch and cut as she fought off the tomcats, opossums, and skunks who tried to get at her babies. I grieved with her as she paced and cried for days after the well-intentioned yard crew took the kittens away at only four weeks.

It took forever for Violet to trust me. I’d stand like a statue at my window week after week as she ate the scraps I’d brought for her. At first she’d dash off at the slightest movement from me. Then she graduated to eating on the sill if I kept the window closed. Finally I opened the window as slowly as I could and cooed to her until she stayed. I endured many scratches and bites in my attempts to pet her: first just her tail, then her back. As we became more familiar, she allowed me to scratch under her chin.

Now, when I call her name each morning, she comes running across the field and leaps into my window, purring and rubbing against the bars. Her willingness to trust has reawakened my own ability to love.

Sonya Reed

Gatesville, Texas

For most of my adult life I thought sex was the highest pleasure. I could not imagine anything more intense or delicious. Then, after I had been meditating daily for twenty-five years, I found myself involuntarily waking up at 3 AM every night. Not knowing what else to do, I would meditate, and at the end of each sitting I would burst into tears. This continued for nine months. Then one day something changed.

I’d gotten home before my wife that afternoon, so I started to make dinner. While I was waiting for the macaroni to bake, I was doing a Buddhist practice called “labeling”: instead of getting lost in each thought, I simply labeled it. As I was doing this, the room began to get brighter, sounds became more vivid, and my sense of touch turned acute. Everything seemed so intensely beautiful that it began to overwhelm me. A cardinal singing outside, the grapefruit in my hand, even the little pieces of garbage at the bottom of the sink — all were precious.

This state of vivid awareness continued for fifteen days and fifteen nights, twenty-four hours a day. It was a feeling of ecstatic joy. Sex fell to second place.

Stephen W. Leslie

Schoharie, New York

Seven years ago I was single, forty, and recovering from life-threatening complications after knee surgery. That same year I met Pavlik. The following July, a few months after the anniversary of our first date, we hiked around Fawn Lake in a suburb of Boston. Mosquitoes bit our arms and legs as we approached a clearing overlooking a sliver of water dotted with lily pads. Pavlik held my hands and asked if I would marry him. That was it. No preamble. I shouted, “Yes!”

We married in November 2006, and I hoped against hope that I wasn’t too old to become a mom. Doctors were pessimistic. After eight months of trying, though, my body decided to produce one good egg. In January 2008 Simon was born. I was forty-three.

Now I have a spunky three-year-old boy who is showing his father and me how to find joy in the smallest things.

“Let’s do a parade,” Simon announces. “Daddy, you play drum. Mommy, you play the flute.”

We are a strange-looking band. Simon strums his blue ukulele and leads us from the living room to the hall to the kitchen. Pavlik taps a toy drum and takes short steps to let our toddler stay in the lead. I tag along behind, blowing notes on a plastic recorder.

The ukulele is out of tune. The drum is off the beat. My recorder playing is a random bleating. It is the most beautiful cacophony I have ever heard.

Linda K. Wertheimer

Lexington, Massachusetts

In my late fifties pain was my constant companion. My hip joints had deteriorated to bone rubbing against bone, and just standing or walking was difficult. The osteopathic surgeon winced when he saw my X-rays and agreed that hip replacement was my only option. But, he told me in the gentlest way possible, I had to be more fit before he could safely do the surgery. Because regular exercise had been too painful for me, I had gained a lot of weight. He strongly recommended water aerobics.

What? Go out in public in a bathing suit? I hadn’t inflicted the sight of all my flab on the public for decades. Even at the beach I wore rolled-up jeans. But my health came first. I signed up for an after-work class at a nearby gym. My first impulse was to wear baggy shorts and a T-shirt in the water, but I rejected it and bought a swimsuit that covered the worst of my features.

I showed up at the pool feeling self-conscious and ready to endure scornful glances. Awkwardly I descended the steps into the shallow end and joined the group of women already warming up. It soon occurred to me that no one cared how I looked. To the other older women in the class I was a welcome addition, and to the younger swimmers I was essentially invisible. It was liberating.

As I began to move around in chest-level water, I had another wondrous realization: I didn’t hurt! My limbs moved in ways they hadn’t for years, and there was little or no pain. I could even swim short distances without discomfort. Buoyant and joyful, I rediscovered my love of the water: its silky touch against my skin, its gentle resistance as my body moved through it. I wanted to do this forever.

Carol A. Thomas

Colfax, California

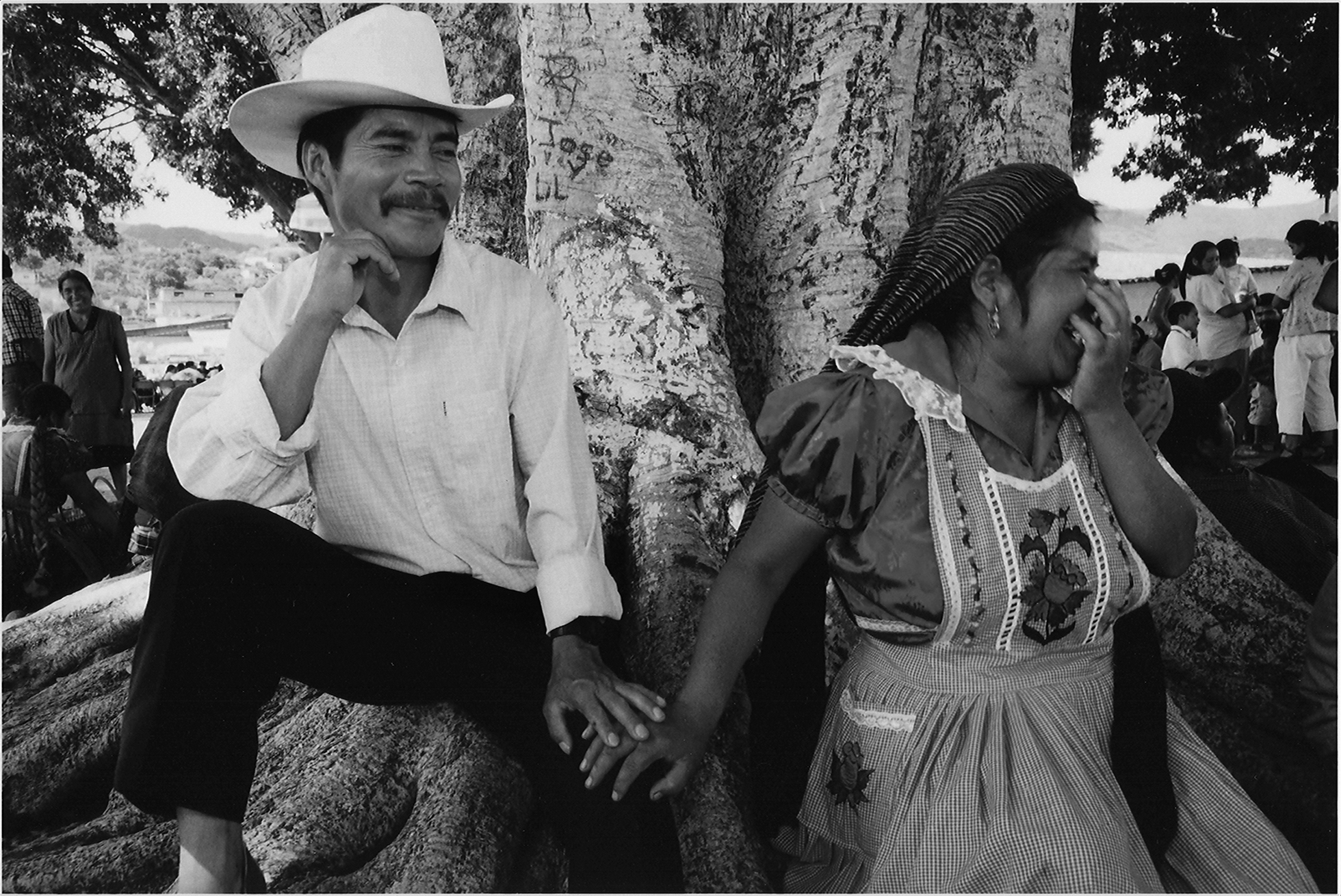

It was August in New Mexico. He picked me up from work and drove me to a park, where we lay on a blanket beneath a tree. Some kids were roller-skating and playing on swings. The tree was huge, and the roots pushed up under the blanket. I was a thirty-six-year-old lapsed-Catholic Latina married to another man. My companion was ten years younger than I am, a Muslim from East Africa who lived in a closed community. We ate chicken, coconut milk, tortillas, chiles, olives, and chocolate. (If we’d learned anything over the previous few months, it was that mixing cultures tastes good.) After we ate, we lay shoulder to shoulder, hip to hip, ankle to ankle.

“You are ruining my life,” he said.

“How am I ruining your life?” I asked.

He said no one had ever understood him the way I did. It was better than having a twin, he told me. “And every day, every minute, it is more.”

He took a leather bracelet from his wrist and set it on the blanket beside us. I picked it up and tied it around my ankle.

“Is that really so bad?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said, “because I want to be with you, but I can’t.”

Two weeks later he left me.

It’s been nearly a year, and he is still the first person I think of when I wake up and the last person I think of before I fall asleep. I don’t know why I’m writing this. I can’t see the use in words if they won’t make him come back.

Name Withheld

When I was twenty-three years old, I survived a traumatic experience that left me afraid of almost everything. For years I got up many times each night to check the locks on the doors and windows. I refused to go anywhere by myself after dusk. I hovered over my children, keeping them in view at all times. They were not allowed to play in the yard or ride a bike or walk to a friend’s house without me.

But now I am tired of being afraid.

Recently I decided to walk alone in the woods for thirty minutes, hoping to make it a daily practice. I headed to the wooded trail when it was sunny, carrying a backpack containing aspirin, band-aids, a flashlight, enough food for three days, hand sanitizer, and a big knife. I walked tentatively, jumping every time an acorn dropped or a twig snapped. I ran into a web and worried that a poisonous spider had gotten in my collar or nestled in my hair. I was startled by an owl. A jogger came up behind me, and I screamed out loud.

Then I began to hear what sounded like a horse, its hooves thumping fiercely. I came upon the source: a doe who’d gotten her snout trapped in a wire fence and was trying to free it. When I approached, she bucked and kicked with such vigor that I worried she would hurt me, but I got close enough to touch her and spoke softly, hoping she could sense my kind intentions.

“You have nothing to fear,” I whispered. “I’m going to free you.”

Her breathing was heavy and irregular, and she did not look at me as I reached out and lifted the fence from her scratched nose. She gave one violent jerk backward, leapt over the fence, and ran away, white tail flashing. She was free.

I kept walking, still in awe of that powerful creature and feeling a sense of joy I hadn’t experienced in a long time. I’m pretty sure I was smiling. I was free, too.

L. Richelle Snyder

Columbia, Missouri

My wife copes with debilitating conditions that would overwhelm most people. Multiple car accidents have left her with chronic pain and fatigue for the past fifteen years, making her unable to work. Throughout this challenging period there has been one constant bright spot: “date night,” our euphemism for making love.

Every Friday evening my wife and I have dinner, perhaps watch a movie, and then get out the pipe and the cannabis. She is legally able to purchase medicinal marijuana in our state. Although it’s not prescribed for use as an aphrodisiac, it serves that purpose for us. The joy we experience then is the healthiest part of her life.

When one of her doctors heard we had such an active sex life, he was both perplexed and pleased, as patients in her condition typically don’t enjoy sex. The combination of the cannabis, her natural sexuality, and the enormous trust and love we feel for each other makes every encounter seem new. After making love, she will often say, “Still the best thing in the world.”

Name Withheld

Growing up, I was overweight and never popular with the boys. They either ignored me or called me names like “fatso” and “tub o’ lard.” My own brothers were among the name-callers, and my father didn’t seem to want anything to do with me. I figured I was disgusting to all males because of my body.

In high school and college I managed to find three boys who would date me. One was gay. The other two just wanted to use me for their own pleasure and convinced me that this was as good as I would ever get. Healthy intimate relationships with men were beyond my reach.

In my twenties, under the guise of feminism, I became a hater of all things romantic. I believed women were giving away their power by letting men open doors for them and pay for their dinners. Those who canceled plans with female friends to go on a date with a man were traitors and not worth my time. Give me ten minutes, and I could find something wrong with any guy one of my friends was dating. (This left me with few friends.) I even had warnings for my gay and lesbian acquaintances. In my wise opinion any romantic relationship that required one to be vulnerable and dependent would lead only to rejection and shame.

Weddings were a favorite target of my disdain. I had no patience for this twisted fairy tale in which powerful women pretend to be virginal, helpless princesses. As far as I was concerned, being taken care of by a man for the rest of my life would have been a form of suicide.

After years of rage, I got tired of being lonely and feeling unlovable. Maybe the reason boys had never liked me wasn’t because I was undesirable but because I thought I was. What had kept me isolated was my inability to believe that I deserved to be seen and accepted for who I was, inside and out.

When I started dating again at thirty-four, I hadn’t been in a serious relationship since college. I met a man who seemed to adore me, but my fears emerged with him in dramatic ways: crazy demands for his time and attention, anger at his kindness and compassion (I accused him of having no backbone), sexual exhibitionism, and a total refusal to show weakness. I was determined to protect my independence.

Miraculously he stayed with me through all of my acting out, and I came to see that he was not so different from me. He wanted to love and be loved, to find that balance between independence and dependence within a relationship. And I came to believe that I am a beautiful woman, inside and out.

That man is now my husband. He is seven inches taller than I am, and when his arms encircle me, my head fits perfectly under the curve of his chin. It is the best feeling in the world.

D.H.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

I discovered I was HIV positive when the test first became available in 1985. I was working as a nurse caring for AIDS patients at the time, and I was devastated. Almost nothing was known about the disease, there were no drugs to treat it, and everyone who had it was dying. But, come Monday morning, I had to uncurl from my fetal position and go back to work.

As time went on, I developed AIDS-like symptoms but was still able to do my job. On one occasion I watched a patient balance his checkbook, knowing that he would probably be dead within a month, and I thought, What’s the use?

Then another patient told me about “AIDS rides” — charity bike rides that lasted from three to six days and covered hundreds of miles. I lived in Washington, DC, at the time, and I registered for the Philadelphia-to-Washington ride.

I was not an experienced long-distance bike rider, and cycling ninety miles a day was excruciating at times. At night the riders camped in tents and shared meals. There was laughter and encouragement, but also flat tires and heat exhaustion. We were all tired and sweaty and had “helmet hair.”

One horribly hot day I went to use the Porta-John at the campground where we’d pitched our tents. I locked the door, smelled that oh-so-familiar scent, and thought to myself, I’m using a Porta-John in the middle of nowhere on an AIDS ride. Life just does not get any better. And I meant it with every aching bone and muscle. Was I delusional from the heat, or had I discovered a new expanded consciousness?

It wouldn’t be the last time I’d cry tears of gratitude on an AIDS ride. Over the years I was able to participate in seven more.

Charles Fiorentino

Washington, DC

In January 1972 I was stationed at Fort Gordon, Georgia, and receiving training to become a military-police officer. The rumor was that our next stop would be Guam, for dog training, then on to the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam. Eight months prior I’d been marching in the streets to protest the war. I could not become an MP. I just couldn’t. That weekend I went absent without leave, figuring the army would not want a man of my ilk in its ranks.

I boarded a bus in Augusta on Saturday, knowing if I wasn’t back by midnight on Sunday, I would be wanted by the U.S. government. This, believe it or not, was not my biggest fear. My biggest fear was that I was about to break my father’s heart. I was heading home to see him. A navy veteran of two wars, he was very much in favor of this one. He agreed with former presidential candidate Barry Goldwater that we should bomb those “commies.”

My dad and I were not close. I was the eleventh child of twelve. Mom had died when I was young, and he’d turned to scotch to ease his pain. As soon as I entered his house, he knew something was wrong. I was shaking and could barely get the words out: “I’m AWOL, and I’m thinking of going to Canada.” I waited for his reaction.

“Son,” he said, “I advise you to go back, but if you feel strongly about it, I will go with you.”

Despite his beliefs he saw the pain on my face and was there to comfort me. I broke down in tears and told him for the first time that I loved him.

A week later I took his advice and headed back to Fort Gordon to face whatever was in store for me. It didn’t matter what the army did. My newfound relationship with my dad gave me the strength to face it.

T.D.

Lindenhurst, New York

As a kid I believed I had super powers. I might be playing in my room, or making mud pies in the backyard, or rolling recklessly down a hill on my Big Wheel, and the world would just melt away. My eyes would stare at nothing. Butterflies in my stomach would send tingles throughout my veins and make my hair stand on end. Images would flash in my mind. I’d feel my lips moving, but no words ever came out. I might drool a little.

Each time it happened, I took it as a sign that my powers were intensifying, that this might be the day I could finally shoot energy from my fingertips. I felt special.

After the moment had passed, feeling like I might puke, I would thrust out my hands, fingers spread as far apart as I could, and concentrate on sending the powers out. When nothing happened, I would tell myself I was in the wrong place, or that maybe I was just too young and had to wait, like how I had to be ten before I could wear lipstick outside of the house.

After a while I began to think that maybe my powers were not good but evil. Sometimes I would wake up under my bed. The “power” started to become too great — too much nausea, too many pictures going through my mind too fast. I decided to tell my parents.

When I told my mother and father that I was having “bad feelings” and that I was afraid, they accused me of making up stories to get attention. I told them many times over several years before I eventually stopped mentioning it to them.

The day in high school that I bit through my tongue and forgot my name caused my parents some concern, but not enough for them to tell the doctor at the hospital about my “bad feelings.” I had another incident in college while waiting for my thesis paper to print. I woke up strapped to a gurney. This time a neurologist told me I had epilepsy and that my bad feelings were focal seizures.

My form of epilepsy is controllable, and my last seizure was in 1996. My parents have never apologized for not believing me.

K.S.

Nashua, New Hampshire

Long before I had any sort of meditation practice, and even before I was able to escape the various abuses I had endured in childhood, I knew spontaneous moments of joy. They came without warning, flooding me with a sense of well-being, no matter the circumstances.

Once I was walking to the store the morning after a fight between my parents, and suddenly a warmth flowed from my heart to my limbs and back again. I was in love with the wind blowing through the trees, with the songs of the birds, with the feel of the sidewalk beneath my feet. No one thing was the object of this affection: I loved all of it.

Then there was a night when, as an adult, I was moved to turn off the television and just listen to the sounds of the house settling. I felt oneness with the cooling bricks, the rafters creaking above my head, the ticking furnace. For that short time there was nothing in the world but me, the house, and the dog asleep in my lap. I was complete.

Even now I might walk the track behind the razor-wire-topped fence that surrounds the prison yard and look up and see the wide Kentucky sky, containing every shade of blue and peppered with at least five different types of clouds. I’ll stare in wonder and know that I am a part of that sky, and so are my fellow inmates. I know this with absolute certainty — and just like that, there is no fence.

Paul Stabell

Ashland, Kentucky

The first time I looked into Magic’s eyes was when I picked him up with the intent of getting him out of my house. My twenty-something son claimed he hadn’t noticed when this clearly sick, skinny, mangy black cat had wandered through our open door. Fearful Magic would infect my own two cats, I scooped him up in my arms. That’s when I happened to look into his eyes, and some communication took place that bound me to him.

I took Magic to a veterinarian and had him neutered and got him a full checkup and shots. Then I brought him home and put a flea collar on him. He immediately disappeared for six weeks. When he returned, I was ecstatic. I noticed that the flea collar had rubbed away the fur around his neck. I took it off and apologized and promised to take better care of him.

Magic lived with me for fifteen years. He was the one being who could smooth away all my rough edges. He slept with me every night, letting me hold him for just a short while before I fell asleep. I always wished he would stay longer in my arms.

At the age of about twenty Magic developed a tumor on his leg. At first it didn’t appear to affect his health. Then his condition worsened and his appetite diminished, until finally he spent all his time on my bed, obviously in pain. When he would not lift his head or look into my eyes, I felt it was time. I arranged for a veterinarian to come to my house the following day and put him down.

That evening Magic allowed me to hold him in my arms the whole night as he purred. I tried not to sleep, so as to savor every moment. Holding him all night long was both the best and the worst feeling in the world.

Deena Eber

Burton, Washington

On the night of my birthday I crept out of bed, where my boyfriend was still asleep, and went to the kitchen for another slice of my cake. I’d wanted a second slice hours ago, but I hadn’t wanted to look like a pig.

The light flicked on, and my boyfriend caught me with pink frosting on the edge of my mouth.

“Why are you sneaking cake?” he asked.

Could I tell him the truth: That I didn’t want him to know how much I could eat? That I wasn’t able to enjoy the cake in his presence? That I’d struggled with eating disorders in the past?

“You don’t have to do that,” he said. “I’m not judging you.”

We sat in the living room and shared a slice. I’ve never tasted another piece of cake that satisfying.

Kristin Conroy

New York, New York

Three months ago my long-term girlfriend left me. We’d both known it was over, but she was the one strong enough to walk away. On the day she returned her house keys, I made an appointment to get a prescription for Prozac.

I had battled depression in my teens, and I told the doctor that I knew I would get over this, but right now I couldn’t stop crying. I just needed something to get me back on solid ground. He wrote me a prescription for sixty milligrams per day and sent me on my way.

In a matter of weeks my body began reacting to the drug. Physically I had sweats and chills, lost my appetite, and was awake all hours of the night. But the most disconcerting effect was on my emotions: I had none. Happiness, sadness, anger, excitement — they were all gone. I sometimes recognized an occasion when I should feel one of them, but I felt nothing. It was like living in a sepia photograph of my life: all my experiences were cast in dull shades of brown.

When I finally stopped the medication, the emotions I hadn’t been feeling came back in force. If Prozac had been sepia toned, withdrawal was in technicolor: vivid and terrifying. I swung from depression to mania. I drank too much and slept too much. I wondered how much longer I could take this.

One day I was at the supermarket, trying to restock my pantry and get my life in order. The wheels of my shopping cart rattled. In the cereal aisle I took a moment to debate puffs versus o’s, and I heard a pop song playing in the background, with an uncomplicated lyric about love. I stopped and listened, and the realization slowly came to me: It was over. She was gone. There was nothing I could do to get her back. And I felt sad, but not destroyed. For the duration of the song I let the sadness wash over me: a pure, unadulterated emotion. It was beautiful.

E. Hemenway

San Francisco, California

I was twenty-four and shy when I decided to try stand-up comedy at a club in New York City. Each fledgling comic was given three minutes on stage, but I wasn’t sure I had enough decent material even for that. My worst fear was that I would throw up.

Most of the comics were pretty bad: a lot of swearing and shouting and predictable jokes about the male sex organ. I was scheduled to go on last. The longer I waited, the more nervous I got. Finally, at 11:56, my name was called, and I walked into the spotlight to say things I hoped would be funny.

The other comics were in the audience, and the atmosphere felt like a party. I wasn’t as concerned about getting laughs as I was about being heard over the noise. But as soon as I spoke, the crowd grew still. For the next few minutes that roomful of strangers was with me. There wasn’t much outright laughter, but I saw some smiles and even got a guffaw. At 11:59 I came offstage to cheers and applause. I was no longer shaking, and I hadn’t thrown up.

I left the club and hailed a taxi to take me to a subway station. When I told the young cabby what I’d just done, he said, “I’ve always dreamed about doing something like that.”

“You should try it,” I said.

“Nah,” he said. “Me, I’d rather listen.”

I paid my fare and overtipped the cabby, leaving myself barely enough cash to take the subway back to the run-down apartment a friend had lent me in Queens. Walking from the subway stop to my friend’s address, I practically floated through the deserted streets. For a moment the city seemed solely mine. I was young and poor, and I had a sore back from sleeping on other people’s couches, but never had I felt more ecstatic than I did that night.

Robert McGee

Asheville, North Carolina

The day he points a gun at me while I cower in the corner of a closet, pregnant and terrified for my baby, is the day I decide to leave him. I obtain two secondhand dresses and go to a couple of job interviews. Against his objections I get a job and work and save and move to a spare bedroom in a co-worker’s house.

Morgan is born. She isn’t a good sleeper. At first she wants to be held sitting up all night, or she’ll cry. Then she wants to nurse every couple of hours. Morgan and I have to move out of my co-worker’s house because of the late-night disturbances, and I have no one to help me pack. The sleep deprivation is making me hallucinate, and her father tracks us down and breaks into my car and steals her stroller. On the rare occasions when my daughter’s asleep, I look at her and weep.

Then one day she starts crying for no reason, and I can’t get her to stop. The first day she cries for three hours. The next day, four hours. I call the doctor and take her in, but I’m told there’s nothing wrong with her.

My baby cries every time I put her down, so I hold her continuously, even when I shower and brush my teeth. But it’s constant motion she wants, so I walk her and bounce her on my knee till I’m exhausted. We are alone. No one comes by with food or offers to hold her while I go to the bathroom or prepare a meal. Mothers aren’t supposed to be alone with their babies. For millions of years they have had other people around to help.

We have to move again. While I carry boxes down the stairs, Morgan cries and rolls herself across the carpet, getting red and sweaty. I feel guilty for having left her for those few minutes. She cries thirteen hours a day now. She is three months old.

In the new place, a hundred miles from the old one, her crying begins to wane. I lay her on my lap facing me and kiss her round belly, her chest, her neck. Then she makes a noise I’ve never heard before: Heh-heh. I want to hear it again, so I kiss behind her ear: Heh-heh. Is she laughing? Oh, yes! It’s like bells! Like bubbles bursting! I kiss her and laugh with her. Such joy, such bliss.

L.B.

San Francisco, California

In 1975 I was a ten-year-old tomboy who wanted to play baseball in the same league as my brothers. At the time girls were not permitted to play Little League ball. The fact that my younger brother could play but I couldn’t was a huge insult. My mother was unsympathetic — my boyish behavior was an embarrassment to her — but my father never treated me any different from my brothers.

One day that spring my father instructed me to get into the car. Not knowing what was happening, I accompanied him on a trip to the Little League office, where registration was underway. As my dad and I approached the table, one of the four men behind it said, “Hey, Mr. Lyons. You already registered your boys, didn’t you?”

Dad said he wanted to sign me up. When the man told him I couldn’t play ball, Dad mentioned some articles in the newspaper about lawsuits in California. I did not know what this meant, but I recognized the tension that followed. I slid behind Dad’s back, where my nose brushed his cotton shirt.

The four men adjourned to an adjacent room and closed the door. When they emerged, the one in charge said, “She can play ball, but if she gets hurt, it’s on you.”

“She ain’t gonna get hurt,” Dad responded. He seemed more annoyed by that comment than by their initial refusal. He wrote a check, and we left.

I was quietly excited in the car. My dad had stuck his neck out for me. I understood later that, as an introvert and intellectual, he didn’t fit in well with his blue-collar peers. Now he was liberating girls to play Little League ball, drawing unwanted attention to himself. But he had done it anyway.

That summer I was one of two girls who played on Little League teams. I continued to play for several years and was the first and only girl to play in the senior division.

Cecilia C. Lyons

Louisville, Kentucky

When the prison yard opened, I left my cell and headed out to the track, as I did every day, for my routine jog. But this morning seemed different somehow. The air was especially crisp. I could actually see blue sky instead of the usual haze of brown smog. I could smell the tantalizing scent of spring in the air and couldn’t help but feel exhilarated by it.

The usual array of shufflers and strollers in their prison blues ambled along the quarter-mile track, reminding me of Shetland ponies resigned to their fate: circling round and round, eyes cast down, going nowhere. I joined their ranks but didn’t adopt their mind-set.

My attention was drawn to the empty area encircled by the track, a vast expanse of lush green grass, inviting but absolutely off-limits to inmates. Guards kept watch from gun towers located behind double coils of razor wire.

That grass was calling me, and I teased myself with the thought of breaking free from this slow parade of prisoners and sprinting across it like a young colt. At first I resisted the urge with all my willpower. Then my self-restraint seemed to float away on a spring breeze.

I bolted onto the vibrant green no man’s land. For a second I expected a shot from the guard tower to stop me in my tracks, but it didn’t come. Probably the guard was dozing or studying the latest issue of Nude, Naked, & Nasty. I didn’t really care. All I knew was that there was still a layer of rubber between me and that delicious, cool grass. So I kicked off my stinking state-issue deck shoes, and for the first time in seven years I felt the delight of grass between my toes. Even if it had been the last sensation I’d ever experienced, it would have been worth it.

Jeri Becker Nager

Forestville, California

After being married for twelve years, I cheated on my husband, then started therapy. When my therapist asked what I really enjoyed doing, I panicked and tried to think of something besides what I’d immediately thought of: having sex. I had four young children, a career, and a husband, but sex was my favorite thing.

I got divorced five years later. Afterward I slept with men I didn’t particularly like but who enthralled me in bed. Then, when I was forty-four, I met twenty-one-year-old James. He and I spent years constantly fucking, and I started having orgasms during intercourse. But after seven years together I decided I didn’t want to make a life with him, and we parted.

One day I was home in bed with the flu reading Erica Jong. She was describing in exquisite detail what it was like to stand in her kitchen and eat a sandwich with her husband and realize how much she loved him. Suddenly sex seemed beside the point if I didn’t have a relationship that would stand up to eating together in the kitchen on an ordinary day.

Name Withheld

I was standing before a roomful of parents for “Back to School Night” when all at once I found myself unable to speak, my whole body heavy, unsteady. A woman in the front row jumped up and said, “I think you’re having a stroke.” She helped me lie down, and a man covered me with his jacket while someone else called 911. I lay there, terrified, as a hemorrhage flooded the right side of my brain, paralyzing the left side of my body, giving me double vision, slurred speech, and the worst headache I’d ever felt. On a gurney racing toward the waiting ambulance, I passed the aghast principal and tried to say, “Tell my kids I’ll be back next week.” I’m not sure what actually came out of my mouth.

It took a long, hard month of inpatient rehab before I could return home. I couldn’t walk without clinging to a handrail or eat without food dribbling from my mouth. It took three more months of daily physical therapy before I could hobble from my front door to my car, and another six months before I could drive.

Throughout that first year I grieved the loss of the person I had been: adventurous global nomad; lithe dancer; energetic backpacker; dedicated high-school teacher. I had always said that I would teach until I turned sixty and then join the Peace Corps. How naive that scheme now seemed.

Six years later I have not regained the use of my left arm or hand, and I still walk haltingly with a leg brace and a cane, but I can visit my favorite health-food store and buy my own groceries. I can go to the movies with friends. I can type quickly enough one-handed to advocate online for causes I support. I can care for my cats, cook, clean house, pull weeds, tend the vegetables I’ve planted in my raised beds, and drive to a nearby marina to sit on a bench overlooking the San Francisco Bay.

As satisfying as such activities are, the best moments come when I can forget my body’s limitations through sharing a deep belly laugh with my granddaughter, or watching a hummingbird sip nectar from my Mexican sage, or being deep in prayer, or helping a friend who’s suffering. In moments like these I experience the same joy and purpose I used to feel climbing a mountain, and, despite all that I’ve lost, I’m filled with gratitude.

Elizabeth Claman

Richmond, California

My nine-month-old daughter, Trilby, suffers from hypotonia, a condition where her muscles lack tone and strength. There’s hope for a full recovery, but in the meantime she gets constipated and can’t move her bowels for days, which causes her great pain. Sometimes she wakes at 5 AM screaming, and my wife and I take turns getting up with her.

I calm Trilby by holding her tight against my chest and singing her campfire songs I learned as a kid. Once she’s stopped crying, I take her to the couch, where she puts her face against the window. The moon’s soft glow trails off in the west. A scampering cat might catch her attention, or she’ll point to the headlights of passing cars.

Eventually exhaustion prevails, and she sinks heavily into me, her head nestled under my chin, her heart beating against mine. The room is silent except for her slow breathing. In these quiet moments I realize that one day she’ll be too big to fit in my arms. She’ll be too busy running around chasing her older brother to sit with me. Then she’ll be running around chasing boys. Daddy will be uncool, a secondary presence. And one day, way down the line, I’ll be too weak to hold much of anything in my arms.

But in this moment of sleep-deprived silence, when I’m still able to ease her pain with my embrace, I feel blessed: my daughter snuggled tight under my chin, her wispy hair against my lips. Staring out the window at the streetlights still on before dawn, I’m as happy as I’ve ever been.

Paul Grafton

Morro Bay, California