I n the early eighties I was part of a production called Crooked Eclipses: A Theatrical Meditation on Shakespeare’s Sonnets, put on by the Boston Theatre Group. We didn’t just recite the sonnets; we learned dozens of them by heart and moved, sang, wept, and wrestled with them. In the six months leading up to the show, lines of Shakespeare would arise in me unbidden as I waited for a bus or shopped for groceries. I count it as one of the best times of my life.

Almost thirty years later, after becoming a poet and teacher of poetry, I discovered Kim Rosen’s Saved by a Poem: The Transformative Power of Words (Hay House). In an era when creative-writing programs and workshops have proliferated like dandelions and it seems everyone wants to be a writer, Rosen asserts the value of becoming a “disciple” to a poem written by someone else. She claims that a poem can be powerful medicine not only for the mind but for the body and soul as well, and she has learned more than a hundred poems by heart, carrying them inside her as teachers, healers, and guides.

Rosen, who has a BA from Yale University and an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College, shares her method of learning poems with students and audiences all over the world: in cathedrals, juvenile-detention centers, school auditoriums, and even the Louisiana Superdome. She grew up in New England and as a child wanted to be a poet, but the dry, analytical approach to poetry taught in high school discouraged her. She turned her attention to theater and, later, spirituality, becoming a teacher of self-inquiry. She was leading workshops on creativity when depression and her parents’ failing health led her to begin learning poems by heart as a healing path. Poet David Whyte was her initial inspiration, but her ultimate teachers, she says, are the poems themselves.

Rosen and I met to talk about poetry, memory, healing, and the origins of language in her cozy home in northern California. It was a gray day, and the rhythmic patter of rain on the skylight provided background for our conversation. As we talked, stanzas from poems wove themselves into the discussion: one of us would begin to recite, and the other would join in, laughing as we groped for lines, honoring the source that feeds both our lives.

KIM ROSEN

Luterman: What do you say to a person who tells you, “Poetry makes me feel dumb, like it’s some puzzle that I can’t figure out. I don’t see that it has any relevance to my life”?

Rosen: [Laughs.] I love to talk to those people. I feel exactly the same way about so much of the poetry I read. For most of my life I was afraid of poetry. It was like this elitist club I hadn’t been invited to join. In fact, many Americans seem to have a fear of poetry. Part of my motivation in writing Saved by a Poem was to help turn that around, to wake Americans up to poetry’s power to heal and enrich us. In fact, my work is not as much about poetry as it is about nurturing the interior life. Poetry can be a lantern that shines into dark places within us. Poems can be powerful medicine for personal transformation.

One thing I might say to someone who can’t relate to poetry is: You don’t have to love all poetry. Do you love all music? Do you love every piece of art you see? Find just one poem you love, and speak it out loud. Your body, feelings, voice, and thoughts will come into harmony when you speak a poem that matters to you, and that can be incredibly healing.

Even people who supposedly don’t like poetry have it all around them, but they don’t realize it, because they don’t call it “poetry.” Every breakup I’ve ever gone through has a song connected to it. I remember John Lennon’s song “Woman.” Oh, my God. [Laughs.] I’d be dead if it weren’t for those lyrics. Those words became the stepping stones that got me across the rushing river of my relationship’s demise.

Find the poetry in the song you sing in the shower, or in the serenity prayer you recite under your breath after your kids trash the living room again. Most, if not all, scriptures were originally written as poetry. Look at the Psalms: “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death . . .” That’s poetry. Why? There is music and imagery in the words. It’s not just the words’ meanings that speak to us; it’s their rhythms, their sounds.

We complain that we don’t understand poetry, but a lot of us recite prayers in other languages, such as Hebrew, Sanskrit, or Latin. Do you understand “Om Namah Shivaya” or “Baruch ata Adonai”? But in those cases there’s a willingness to let it sweep into you and affect you. The same is true of music and art. When you attend a symphony, you lean back, close your eyes, and go for the ride. You’re not thinking to yourself, Now, what was Beethoven trying to say with that particular chord? Most of us don’t analyze a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe. We stand in front of it and observe what happens in our own bodies and minds.

But with poetry, because it’s words on a page, we think we’re supposed to understand it the way we understand a newspaper article. The left brain says, Aha! This is my domain. It wants a literal meaning to the poem. But poetry is the stuff of the right brain — the ineffable, the emotional, the relational — arriving dressed up in the costume of the left brain: words. Billy Collins has a great poem called “Introduction to Poetry.” He invites people to “take a poem and hold it up to the light like a color slide,” but all they want to do, he says, is beat it with a hose to “find out what it really means.”

Luterman: But isn’t it also important to understand the meaning of the words?

Rosen: I think we have to expand our idea of what the word understand means. It’s not just the kind of understanding that comes with the solution of a riddle or a math problem. It can include a kind of revelation that comes through the whole body. Emily Dickinson wrote, “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?” Dickinson is talking about a kind of understanding through feeling and sensation, not through the accumulation of information.

To me a good poem is like a sacred mind-altering substance: you take it into your system, and it carries you beyond your ordinary ways of understanding. I call the nonconceptual elements of a poem — the rhythm, the sound, the images — the “shamanic anatomy.” Like a shaman’s drum, the beat of a poem can literally entrain the rhythms of your body: your heartbeat, your breath, even your brain waves, altering consciousness. Most poems are working on all these levels at once, not just through the rational mind.

When I was in school, I was taught about the meter of the poem — iambic pentameter, dactylic tetrameter, and so on. I was taught the definitions of simile and metaphor, and I remember being quizzed on the rhyme scheme of a Shakespearean sonnet. But no one told me these were consciousness-altering substances! No one told me rhythm could free my mind, a rhyme or simile could crack open my thought patterns, and assonance and alliteration could allow my feelings to flow in new ways.

A man named Christopher in one of my workshops was working with Rumi’s poem “Love Dogs” in a rendering by Coleman Barks. Christopher had been sent to me by his singing teacher, who felt I might be able to help him bring more spontaneity and emotion into his voice. Even in ordinary conversations, his speaking voice sounded as if every inflection had been composed ahead of time.

“Love Dogs” challenges the reader to cry out with longing, as a dog does for its master. It was a perfect poem for Christopher, because that unselfconscious flow of feeling was exactly what was missing in his singing. He learned the poem quickly and easily, but one line always tripped him up: Barks’s version goes, “The grief you cry out from / draws you toward union.” But every single time, Christopher said, “The grief from which you cry / draws you toward union.”

It seems like a small difference, doesn’t it? And the meaning is basically the same either way. When I asked him about it, Christopher said he liked his version better because it was grammatically correct, and Barks’s wasn’t. Never end a phrase with a preposition, right?

Barks could have chosen to be grammatically correct, but he didn’t. There is something more compelling than grammar moving his line: the momentum, the way the energy travels through the body as it is spoken. Say the line both ways, and feel the difference in the sensations in your body and the movement of your breath: “The grief from which you cry”; “The grief you cry out from.”

Luterman: The first version seems neat and predictable, and the second is kind of a wonderful mess, falling over itself and open-ended.

Rosen: Exactly! Christopher’s version shuts tight at the end: “The grief from which you cry.” Barks’s meter is irregular and ends on a weak beat, leaving the energy open and vulnerable: “The grief you cry out from.”

The amazing thing is that when Christopher finally spoke the line the way Barks had written it, his voice broke, and this huge sob came bursting out. He was scared and embarrassed at first. He hadn’t let himself cry in public since he was a kid, so it was quite a stretch for him, but he did it. And that release freed his voice and his spontaneity.

Luterman: At the risk of sounding elitist, isn’t it important that a poem be good?

Rosen: What is “good”? Sometimes I cringe because a poem seems trite to me, only to find out that those words saved my friend’s life when she was going through her divorce. Think about art or music: You love Aretha Franklin; I love Beethoven. You love Rothko; I love Rembrandt. Maybe a certain poem doesn’t sing to me, but if it opens someone’s mind and heart, who cares whether I find it good or bad?

Luterman: You recently wrote a blog in the Huffington Post about this country’s “metrophobia,” or fear of poetry. Why is American culture so poetry-phobic, whereas other cultures revere poetry and poets?

Rosen: Only a few generations ago in the U.S., poetry was much more popular than it is now. My father, who is ninety, still remembers the John Donne sonnet he memorized in grammar school. Poetry recitation used to be a fixture of small-town American entertainment. But over the last few generations we have managed to marginalize the art form. And it’s not just about the rise of TV, radio, and other technologies taking the place of poetry. Did you know that the most popular TV show in the Middle East is Million’s Poet? It’s like American Idol, but the contestants recite poetry. The show has even inspired a TV channel completely dedicated to poetry, an idea that seems unimaginable in the U.S.

So what happened here? I have lots of ideas, but no definitive answer. Writer Eve Ensler says that we live in a country where people have forgotten to think in metaphor. With the loss of metaphor comes a lack of imagination, ritual, mystery, and discovery.

I also suspect that the qualities of openness and humility that the best poetry encourages may have been lost in Americans’ drive for upward mobility. Many poems look behind the superficial masks we wear to the vulnerable self underneath. John F. Kennedy said it beautifully in his eulogy of Robert Frost: “When power leads man toward arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.”

Maybe the U.S. — and please forgive me the audacity of this sweeping generalization — doesn’t want to be reminded of its limitations, its kinship with all life. It doesn’t want to look into poetry’s truthful mirror. As a country the U.S. has been identified with a strong will. We’ve “pulled ourselves up by our bootstraps.” Maybe poetry, real poetry, requires a healthy surrender of willfulness. Maybe it demands a willingness to be changed, to be affected, to reveal our wounds without denial or muscling through.

But with all the crises of recent years, the U.S. seems to be waking up to the need for poetry. I go to places like Ireland, Brazil, and Uruguay that have been through crisis after crisis, and poetry is a central value in these cultures. Supposedly I’m the teacher when I go there, but really I am the student.

Luterman: I go into elementary and high-school classrooms as a poet in the schools, and sometimes the teachers are glad to learn from me about accessible poetry. They’ve encountered only formal poems that were taught badly.

Rosen: I think many schoolteachers in the U.S. approach poetry in a deadened way, as if using a prosthetic limb, because their healthy limb was cut off by the unimaginative manner in which they were taught. Poetry has become, in some sense, a language that only the highly educated seem able to understand. And even though I am one of the highly educated, I can’t figure out why academics choose the poems they do to canonize, because I don’t get most of them.

Luterman: I think that’s changing, though, with the generation coming up. They are reclaiming poetry for their own.

Rosen: It is changing through the Trojan horses of spoken-word poetry, hip-hop poetry, and poetry slams. There’s a nationwide recitation competition now for high-school students called “Poetry Out Loud,” created by the Poetry Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. Hundreds of thousands of students take part in it. Perhaps in ten years poetry will be much more a part of the mainstream.

Luterman: From your mouth to God’s ears. But tell me more about poetry in the Middle East.

Rosen: In the Middle East poetry is absolutely central to the culture. A few years ago I was lucky enough to meet an Iraqi woman named Yanar Mohammed. She was once a successful architect, and she and her family lived in a beautiful home in the suburbs of Baghdad. They went into exile in Canada in the early nineties, and when they returned to Baghdad in 2003, she witnessed escalating violence against women due to the collapse of the government and an increase in the rule of tribal law. She founded the Organization for Women’s Freedom in Iraq, which runs shelters and helps women who have been unjustly thrown into prison, forced into prostitution, threatened with “honor killings,” or caught in the sex-trafficking trade.

Yanar also created an initiative called the “Freedom Space.” The original idea was for Sunni and Shiite poets to come together for a poetry competition. There were twenty-five participants at the first Freedom Space, which took place in a tent on a bombed-out street in Baghdad. Yanar described it as “ping-pong poetry”: someone on the Sunni side would recite a poem, and somebody on the Shiite side would recite a poem expressing the same woundedness and longing. By the end of the first gathering, the distinction between the teams had dissolved, and they were in each other’s arms. After that, the movement began proliferating all over the city and the surrounding countryside. Hundreds of people started coming. Gatherings were held in areas where people had been killed by militias for speaking poetry, and poets risked their lives to travel there. Even soldiers from the Sunni and Shiite militias have joined the movement, to guard the space or sometimes speak poetry from the stage. A few left their posts in the army because they saw these poetry gatherings as a more powerful form of peacemaking. In 2008 the Freedom Space was held at the technical university in downtown Baghdad. A thousand people — Sunni and Shiite — danced and wept and cheered even as bombs were heard in the background.

Learning a poem by heart is . . . a mutual relationship in which you let yourself be changed and healed. The ancient Tibetans used to call it “writing on the bones.” They couldn’t read or write, so they passed down the Buddha’s teachings by memory.

Luterman: Do you think poetry could bridge the cultural divide between Americans and the Middle East?

Rosen: Poetry could strengthen our connection with people not only in the Middle East but in any culture. We need a worldwide Freedom Space. I have a vision of bringing poetry to every gathering of the UN, every peace summit, every World Economic Forum. Poetry would interrupt the dualistic, sectarian thinking and bring everyone into a place where we are connected. Another kind of wisdom could come through.

I experienced this when I unexpectedly found myself speaking a poem to a group of Masai girls on my first visit to the V-Day Safe House in Narok, Kenya. V-Day is an organization committed to stopping violence against women and girls worldwide, and the safe house is a shelter for girls who run away from home to avoid the practice of female genital mutilation and early-childhood marriage.

In the summer of 2007 I visited the house for the first time. I’m a shy person, so it was difficult for me to get to know the fifty or so Masai girls living there. They were shy, too, and hung back, whispering in Maa (their language) and giggling. They understood English, but most of them didn’t speak it very well. Finally I gathered my courage and walked to the kitchen, a room with a mud floor and a wood fire in the middle, where they were cooking ugali — a cornmeal porridge — and cabbage. The girls had been singing beautiful songs and prayers as they worked, but the moment I walked in, they went silent, as if the teacher had entered the classroom. I didn’t know what to say. Finally a tall young woman walked up to me and asked, “Do you remember my name?”

I’d met about twenty girls in the previous couple of hours and could not for the life of me remember which face went with which name. “Salula?” I asked sheepishly.

The girls shrieked with laughter. “That is Salula!” They pointed to one of the youngest girls, who was nine years old and had been rescued from a forced marriage to a forty-two-year-old man.

“My name is Jecinta,” the tall girl said. “Do you know any songs?” I guess she was giving me an opportunity to redeem myself.

“I know some songs,” I replied, “but what I really love is poetry.”

The girls understood the power of poetry because in tribal gatherings, when people want to raise an issue for the community, they write a poem and recite it, and often the schoolchildren recite poems in unison.

Now the girls were all waiting for a poem, but I had no idea which poem to recite. I couldn’t think of one that was appropriate. These were girls who had run away from their families and their tribes; some of them had traveled barefoot through the night for miles to arrive at this safe house, cowering under bushes to hide from hyenas.

I just started speaking the first poem that popped into my head — “The Journey,” by Mary Oliver: “One day you finally knew / what you had to do,” it begins. The poem is about leaving home, turning away from all the voices that demand you stay, risking the sorrow of everyone who seems to need and love you, and walking alone into a wild night in order to save “the only life you could save.”

At the end of the poem tears were running down my face, and several of the girls were crying as well. Jecinta threw her arms around me, and somebody else came up and put her head on my shoulder.

Jecinta said to me, “Who is this woman, Mary Oliver? Is she Masai?”

I shook my head. “No. White. From America. Like me.”

And Jecinta asked, “How did she know?”

Luterman: The poem had opened the door to a place where two people can know each other without ever having met. Is this how poetry became a spiritual path for you?

Rosen: For me there came a point when I could no longer settle on one spiritual teaching and say, “This is the Truth about life.” One says it’s all about emptiness; another speaks of salvation. One says it’s about the soul’s evolution; another says there is no such thing as a soul. One teaches “intentional creation”; another tells us to surrender to what is. I found that all of these were true for me at once, but there was no teaching, no language that could hold these multifaceted and sometimes contradictory truths — no language except poetry. Poetry contained the grit of humanity right next to the vastness of being. The poems I love most hold those two ideas together. I decided that I could no longer be a teacher or follower of one particular spiritual path. The only thing I could be was an emissary of poetry.

Luterman: How have you been saved by poetry?

Rosen: When I was a kid, up to age ten or so, I thought I was going to be a great poet. I think many kids love poetry. All over the world parents speak to their babies and children in poetry: “Little Miss Muffet sat on a tuffet.” Nursery rhymes, Dr. Seuss, the baby babble that mothers croon to their newborns — all have rhythm and rhyme. I think the womb is a poetic place. Your ear is attuned to the meter of your mother’s heart, so all the sounds from the outside are coming through that bum-bum, bum-bum, and you can’t quite hear the words, because you’re suspended in amniotic fluid. So it’s more like whale sounds or a kind of “musilanguage.”

Luterman: Musilanguage?

Rosen: Yes, that’s the word neuroscientist Steven Brown coined for the form of communication that came before actual language. When vocal language began 1.8 million years ago, some archaeologists believe it was musical sound, used to communicate about relationship, emotion, the ineffable. Practical, pragmatic, linear communications still happened only through sign language.

Luterman: So, “Watch out, there’s a saber-toothed tiger on your tail” . . . ?

Rosen: That was sign language. But “I love you, and I don’t know where this feeling came from in me; it feels like the full moon in my chest” — that came in musilanguage, which was far closer to poetry than it was to prose.

I imagine that what we hear in the womb is very much like what the earliest hominids heard from each other. Mothers know this in their bodies. If you listen to a mother cooing to her child, you’ll notice that she uses a singsong musilanguage: goo-goo, ga-ga, si-si, sa-sa. Gradually we move on to words: “Hickory dickory dock / The mouse ran up the clock.” So we recapitulate the linguistic evolution of the species: we are born into language through poetry.

Luterman: So you spent your childhood immersed in poetry?

Rosen: Yes, and then high school happened. [Laughs.] Although there may have been some fantastic programs going on in other high schools, my experience was of having to study The Odyssey and The Iliad and Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” — poems I couldn’t relate to at all.

Luterman: Me too!

Both together: “Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere, / On the eighteenth of April, in seventy-five; / Hardly a man is now alive / Who remembers that famous day and year. . . .” [Laughter.]

Rosen: Today some of those poems have become exciting to me, but back then? Did I care about the siege of Troy or the coming of the British? I was fourteen years old. I was wondering how my hair looked and if my skirt was too short — or not short enough! [Laughs.] So I figured I had been wrong about poetry, and I turned in other directions.

Twenty-five years later I was a workshop leader specializing in personal transformation. I was using breath work, movement, body work, music, ceremony, even swimming with dolphins. Then, in 1994, I found myself in an intense depression. My family was in crisis. My parents had both had heart attacks within months of each other. None of the spiritual or psychological techniques I’d learned could make me feel less lost. And, let me tell you, it’s rough when your work is all about igniting creativity in other people and you don’t have a warm ember in yourself!

When I’m depressed, I clean. The more depressed I am, the cleaner my house gets. One day I was cleaning under a radiator and found a cassette tape covered with cat hair and dust. I blew it off and threw it in the player and began to do the dishes. A man’s voice reciting poetry filled my house. The words reached a place inside me that had felt untouchable. I put down my sponge and wept.

The tape didn’t have a label on it, but I called everyone who had been in my house over the prior few weeks and discovered that it had fallen out of a client’s purse. She told me the speaker was the poet David Whyte, who now leads poetry seminars for businesses and organizations, encouraging creativity in the workplace. A friend had given her the cassette because her father had just died, and he thought those poems might guide her through her mourning. Many people discover poetry during a crisis.

Luterman: I remember after the September 11 attacks, poems were flying around the Internet. People were using poetry to cope with the overwhelming grief.

Rosen: Absolutely. Because where else were they going to turn? Most people aren’t going to read a psychological treatise or a spiritual tract after such a devastating loss. A poem can cut through the mind’s defenses and land you right in the nakedness of the moment.

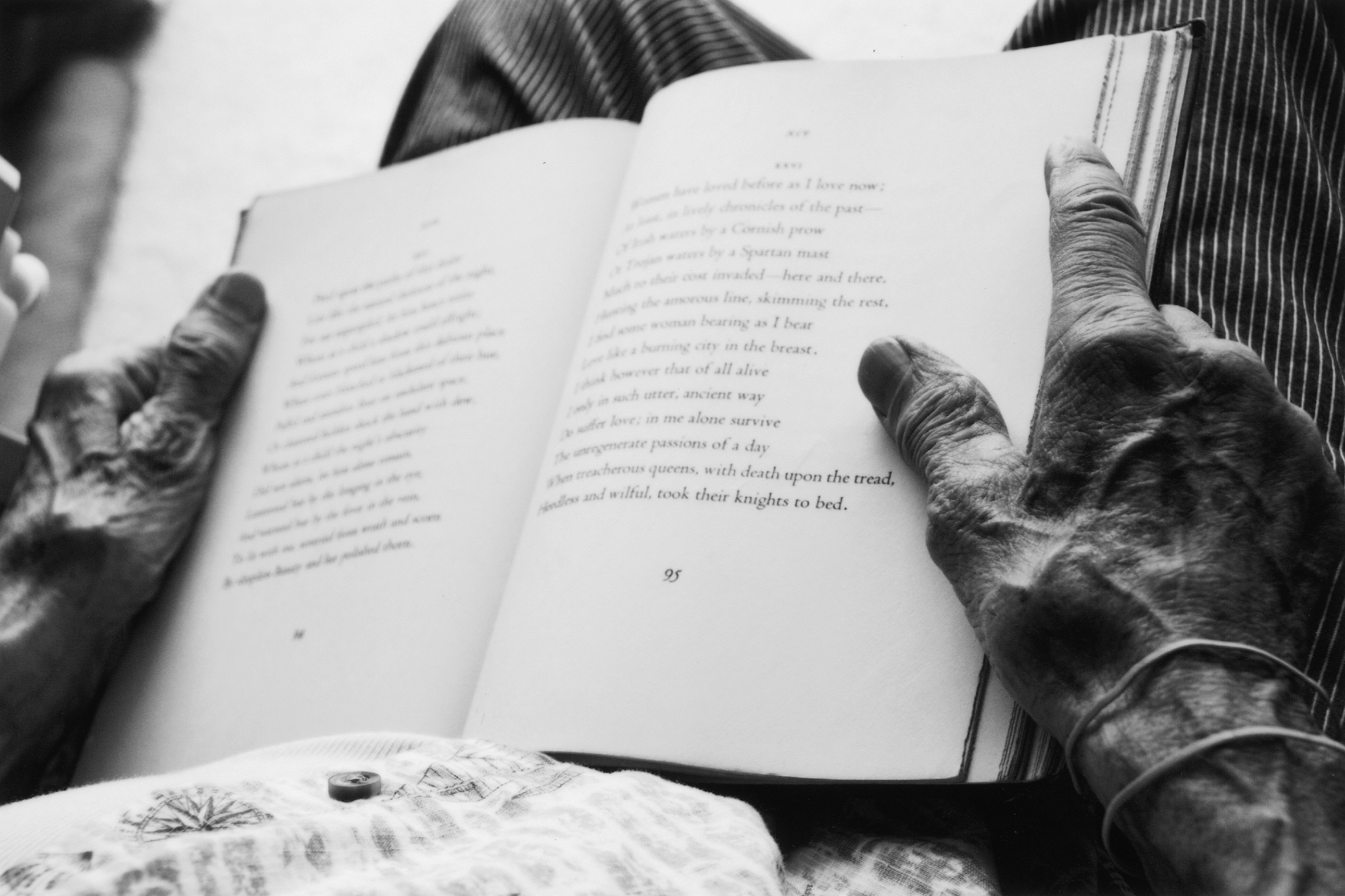

The poetry Whyte read aloud on the tape wasn’t like any I had studied in high school or college. It was the poetry of the inner life: Mary Oliver, Derek Walcott, Rainer Maria Rilke, Rumi, Marina Tsvetaeva, Anna Akhmatova. I was so inspired that I decided to memorize some of the poems, as Whyte had. At the time I was driving back and forth to visit my parents, who were both recovering their health. The Massachusetts Turnpike is one long, straight road: three hours, no turns. I’d place a poem or two on the passenger seat of the car, and when I pulled off at a rest area, I’d gobble up a few lines of the poem and then see how long I could keep them in my mind as I drove.

I didn’t end up merely memorizing those poems; I learned them by heart. There is a huge difference. I don’t even like to use the word memorize if I can help it. For me it reeks of old-fashioned teaching methods: conjugations of Latin verbs and having to recite Alfred Noyes’s “The Highwayman.” (Although I must say, when I look at that poem now, I find it sexy and romantic. For some reason no one brought that to my attention in seventh grade!) Memorizing a poem seems more like conquering it than entering into a relationship with it. Even the suffix -ize gives a sense of enforcing your will over something: privatize, computerize, terrorize.

Learning a poem by heart is different. It’s a mutual relationship in which you let yourself be changed and healed. The ancient Tibetans used to call it “writing on the bones.” They couldn’t read or write, so they passed down the Buddha’s teachings by memory. They knew that taking these teachings into themselves was a bodily experience. In my case I found I could not remember the poems if I did not let each line pull up all sorts of emotions, insights, cries, laughter — some of which I didn’t even know were in me. And it all moved through me so easily with the help of the poems: feelings and memories that had been bottled up for a lifetime. I felt as if I’d come upon an ancient key to healing that our culture had forgotten.

Years later, as I wrote Saved by a Poem, I learned that in ancient Greece the Pythagoreans and others would learn poems by heart so they could recite them at the hour of their death. They believed that speaking poetry raises the vibration of the physical body to ease the passage into the higher vibration of spirit. Even Socrates, who was known to have disparaged poets and poetry, saying they had no place in the ideal state, began writing poems after he’d been condemned to death.

So I’d discovered this ancient mystical practice of learning and speaking poems. The poems carried me beyond my personal self into the place where I became everyman, everywoman. I could fly into any experience through these poems. It was incredibly freeing. As Walt Whitman says in “Song of Myself”: “Every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

It was also like having a retinue of private teachers inside me who would speak at difficult moments — of which there were many. When I visited my parents’ home, the house I’d grown up in, I’d often revert to childhood: I’d sit in sullen silence at the dinner table or become a petulant four-year-old whenever I felt criticism coming my way. Now, instead of clamming up and giving whoever seemed threatening “the look,” I’d hear Mary Oliver whispering in my inner ear, “You do not have to be good.” Or Goethe would warn my prideful temper: “So long as you haven’t experienced / this: to die and so to grow, / you are only a troubled guest / on the dark earth.”

In parts of the Middle East there are Bedouin tribes who are supposedly “illiterate,” but many of the tribe members know hundreds and hundreds of lines of poetry by heart, and they can remember new lines after hearing them only once.

Luterman: In your book you tell about losing all your savings in the fall of 2008.

Rosen: Yes, that October I invested everything in a small fund that a friend had recommended. Two months later my friend called and left a message on my voice mail: Bernie Madoff had been arrested. The fund had been invested entirely with him. We’d lost everything.

I stood there, not breathing. And into that space of absolute paralysis came these words: “Before you know what kindness really is / you must lose things.”

It was a line from a poem by Naomi Shihab Nye called “Kindness.” I’d heard it before but had never really been attracted to it. I certainly didn’t know it was in my memory!

I thought, This is ridiculous! I’ve got to call a lawyer, an accountant, a pawnshop — someone — not recite a poem! But the next few lines unfurled: “Feel the future dissolve in a moment / like salt in a weakened broth. / What you held in your hand, / what you counted and carefully saved, / all this must go.”

I didn’t know the rest of it, so I Googled the poem, sat down on the floor (which seemed like the only appropriate place to sit), and started reading aloud. I read it over and over and over. Those lines carried me through all the clenched layers of survival anxiety into the heart-opening possibility this event offered in my life. That poem became my prayer.

The friend who’d called invited me to stay with her for a few days while we figured out what to do, and when I got to her house, she was holding a copy of “Kindness” in her hand. She had just been reading it to someone else who had lost money. Over the next couple of days we read “Kindness” to each other over and over.

I’ve never been a religious person at all. I suppose you could say I’ve had great spiritual longings, but I’ve never really turned to prayer the way some people do. After that experience I understood why Muslims pray to Allah five times a day and why Orthodox Jews face east and wrap the tefillin [small leather cases containing Scriptures, strapped to the forehead and the arm during weekday-morning prayer]. “Kindness” was the prayer in the little tefillin box on my forehead as I walked through the wreckage of that time. It’s still there.

Luterman: Deuteronomy 6:8: And these words “shall be as frontlets between thine eyes.”

Rosen: Yes, this poem was the frontlets between my eyes, showing me the way. I’ve experienced many revelations as I’ve looked at the world through it. For instance, I had always thought the poem was about how kindness breaks out of you in times of loss. When you have experienced suffering, you can be in kinship — which is the root of the word kindness — with others who have suffered. But it isn’t just about kindness flowing out of us; it’s about kindness flowing into us. The kindness that came toward me in that time of trauma was life-changing. Before, I’d tried to be so self-sufficient, denying I had needs.

There’s a line in a Rumi poem, again rendered by Coleman Barks, that says, “Where lowland is, / that’s where water goes. All medicine wants / is pain to cure.”

Luterman: So poems can be like medicines applied to our difficult circumstances. Let’s say that I am an unemployed single parent struggling with a rocky romantic life. What poem would you prescribe for me?

Rosen: [Laughs.] I wouldn’t just prescribe a poem. I would speak it aloud to you. Hearing a poem in the voice of someone who cares is the real medicine. I might recite Galway Kinnell’s beautiful poem “Saint Francis and the Sow.”

Luterman: “To reteach a thing its loveliness . . .”

Rosen: Yes. He writes about how Saint Francis puts his hand on the sow and blesses her “in words and in touch” until she remembers her own loveliness in her whole body, all the way down through her fourteen teats to the fourteen piglets suckling beneath her.

Or maybe I’d speak a poem from Marie Howe’s book The Kingdom of Ordinary Time. Howe has an uncanny ability to interweave the grit of the everyday — being a single mother, grocery shopping, going to the movies — with a taste of the mystical hidden behind it. She has a poem called “Prayer” that says: “Every day I want to speak with you. And every day something more important / calls for my attention — the drugstore, the beauty products, the luggage / I need to buy for the trip.” I can relate to that.

Luterman: In your book you say that, as a child, you had trouble reading. Has this difficulty affected the work you do now?

Rosen: I’ve always wanted to be able to gobble up books, but I can’t. Reading at a slower rate is almost like having a limp — you can’t rush. When I do read, it’s a deep commitment. As a result I have to be selective, which is painful to me. But the flip side is that, when I read something, I become intimate with it. It’s a different sort of enrichment from being able to read quickly.

The process of learning a piece of writing by heart saved me as a child with undiagnosed reading issues. I couldn’t read whole chapters of textbooks, so I would read the summaries out loud until I knew them. I learned them more through my ears than through my eyes. These days there are schools that take into account each child’s natural learning channels, but in the past many of us were evaluated only on what we could learn through the written word.

In parts of the Middle East there are Bedouin tribes who are supposedly “illiterate,” but many of the tribe members know hundreds and hundreds of lines of poetry by heart, and they can remember new lines after hearing them only once. For generations reciting poetry has been their entertainment around the fire after a hard day’s work. It is their TV, newspaper, and radio. In terms of intelligence, there’s probably no difference between them and me, just as there’s no difference in IQ between a child with a learning disability and one without.

Luterman: What made you choose to focus on poems by others rather than writing your own poetry?

Rosen: When I say my work is about the healing power of poetry, people almost always think I mean writing poetry. The current self-help trend is focused on me defining myself by expressing my voice. I don’t deny the incredible medicine of writing a poem, but there is another kind of healing to be reaped from developing a life-changing relationship with a poem that is already written. If you decided to heal yourself through, say, playing the piano, you probably wouldn’t begin by composing. You’d learn Beethoven’s Minuet in G; you’d learn “Yesterday,” by the Beatles; you’d learn the theme to Doctor Zhivago. With music there’s an understanding that composition is probably not for everyone, but that doesn’t mean you can’t play. With poetry and other written arts, people think, I know how to talk, so I must know how to write.

There’s a lot to be said for choosing a poem and becoming its disciple. Repeat it out loud. See what the rhythms of that poem do to your breathing and your pulse. See how it stretches your voice to a place it never went before. Let that poem show you that you don’t end here; you’re so much bigger. Because if we speak only our own words, there is a possibility that our unhealthy or tired patterns will prevail. But if we take in the words of somebody else, they might shake up our own patterns. Others’ words rattle the “glass bottles of our own ego,” as D.H. Lawrence says in his poem “Escape,” so that we discover we’re more than who we thought we were.

Luterman: With all the challenges facing us in the twenty-first century, from global warming to a crashing economy to wars around the globe to violence against women, how can poetry possibly matter?

Rosen: I think at times of cataclysmic change, poetry is the only language that will do. It’s the only language that speaks of the horror and the wonder, the reality and the mystery. It can hold both questions and answers at the same time without giving a pat solution or a self-help formula. Your favorite poem might be an outcry of rage that frees your voice to fill every inch of your body, mind, and being. Or it might be a poem of the inner life that returns you to a sense of wholeness. The great mystic Hildegard of Bingen said, “When the inner and the outer are wedded, revelation occurs.”

I’m thinking of the poems of Anna Akhmatova, who was writing in the middle of the Russian Revolution. She was forbidden to write, so she slipped lines of poetry to her friends, who learned them and carried them in their hearts and minds until they could be printed. I’m thinking of the poems that people recited for each other in the concentration camps, of the salvation that poetry brought them. Poems are holy without being denominational. Like prayers, they take us back to the wholeness that is invincible.

This is not the first cataclysm in the human story. There have been many others: wars, violence, plague, hunger, natural disasters. In those moments some of the greatest poems of all time were written, pressed out of the tectonic friction of human history like diamonds.