Sometimes you are sick and cannot face your responsibilities; you get headaches, viruses, and just plain tired. Like this morning, halfway through preparing breakfast, you feel your head begin to spin, and you look up from the pot of bubbling oatmeal to Dixon, who is reading the paper, then to Anna beside him, staring into the distance and humming some tune that’s foreign to you, fingers twisting her long, dark hair. They seem miles away and recede farther the more aware you become of your burgeoning flu. You serve them each a bowl and hear them ask for spoons and milk as you climb the stairs to your bedroom. From your bed you hear the clatter of Dixon taking over, carrying on without you. Sometimes you can’t decide which is worse: fulfilling your obligations or letting them slip away.

The door opens, and Dixon tells you he will meet Anna at the school bus later — you should rest. Anna comes up to say goodbye; then you listen to them descend the stairs. You hear the front door, the truck’s engine, and, finally, silence.

The fever takes over, and your mind wanders in and out of a hazy sleep filled with dreams of faces you cannot place. It is the kind of sleep from which you wake with a pounding heart, feeling isolated and heavy. You breathe deeply and pull the covers closer and tell yourself you’re OK, drifting back into a dream.

You wake to the sound of Dixon’s voice: “I forgot to meet the bus. She’s not there; she’s not here. Do you know where she is?”

You blink back his question, think very carefully while you will your eyes to water and shed the residue of your sleep. Early-evening rather than morning light seeps through the blinds.

“You forgot?” you say, because that is where you are stuck; that is where the deal fell through. “You forgot?” you say again, because you aren’t sure if you said it aloud before and because he isn’t answering but pacing in a circle and pulling on his lip. It is 5:35 P.M.

“I’ve looked everywhere. I’ve gone to the school; I’ve called Kate — nothing. I think we should call the police,” he says, and he looks at you in a way that reaches into you, a plea for mercy.

“The police,” you say and stand. The room spins around you, so you close your eyes and trust the wall. He takes you by the shoulders and eases you back to bed. “My God,” you say. You pick up the phone and stare at the numbers until he takes the receiver from your hand and dials the number himself.

“I think our daughter is missing,” he says in a voice very different from the one you’ve known for more than ten years. He presses his forefinger and thumb into his eye sockets, recites the day’s events between sighs while you sober up, open the blinds, the window. You listen closely to his report and scan the yard. No one in sight, just sculpted rhododendrons and hydrangeas, a single willow backed by acres of wild cedar, pine, maple.

“I was working,” you hear him say. “I just didn’t realize the time.”

And you, bundled in bed, letting the day slip by, flashing through fever dreams, leaving Anna to walk the mile home alone in the fading light of early November. You should have been there; you know that mothers are supposed to be there.

Dixon hangs up the phone and says, “They’re on their way.” He tries to hold you, but his touch is onerous, and you fight the urge to push him away. Instead you grab the phone.

“I’m going to call Kate,” you say. “Anna must be there with Jess. Did you drive up the street? Are you sure she isn’t somewhere along the way? Did you check her bedroom?”

You know he has, but you have to be sure. You want to do these things yourself: make the calls, drive the streets, search the house, the woods — did he check the woods?

“I came home before I checked the woods,” he says, “just to be sure she hadn’t shown up here.”

“Goddamn it, Dixon, it’s getting dark. What if she’s out there somewhere?”

“The police are coming — what do you want me to do?”

“I want you to find her,” you say and dial Kate’s number. He turns away from you. You hear him on the stairs, then the front door closing.

“Kate, is Anna there with you?” you say, and she says no, she hasn’t seen her. She thought it was strange you weren’t there to meet Anna, but she figured you were on your way. You think: What kind of person just walks away from a seven-year-old beside a busy roadway and miles of woods? But you don’t say that; instead you ask her to call if Anna shows up. You hang up the phone and search the house, calling, “Anna!” as you flip on the lights and make your way downstairs. The house is vacant and cold, quietly mocking you.

The phone rings. You run to answer. It’s your neighbor Alice, checking to see if Anna made it home yet.

“Where were you?” you say. “Why didn’t you bring her home to me?” You slam down the receiver, and the front door opens. It’s Dixon and two police officers, who are quiet except for the squawking of their radios. The hallway stretches out before you, longer than it should be, and you reach for the wall to steady yourself.

You give the officers the details as you know them. Dixon repeats his story and sucks in several penitent breaths. You show them photographs, and Dixon catalogs her appearance: dark hair that falls in curls down to the middle of her back, hazel eyes, dimples. “She is wearing bluejeans, a red sweater, her favorite red high-top sneakers,” he says. “She has a coat with her, a purple waterproof jacket, but she doesn’t like to wear it.”

The officers scratch notes and glance at photographs, and you think they will miss it. You think they won’t know.

“She is a radiant girl,” you say.

They stop writing and look at you. You feel the weight of Dixon’s hand on your knee.

“Does she have fingerprints on file?” the blond one asks.

After cups of coffee and paperwork have filled your night, after you’ve watched Dixon disappear into the woods with a dozen others to search, you will think again of this question. You will begin to understand why he asked.

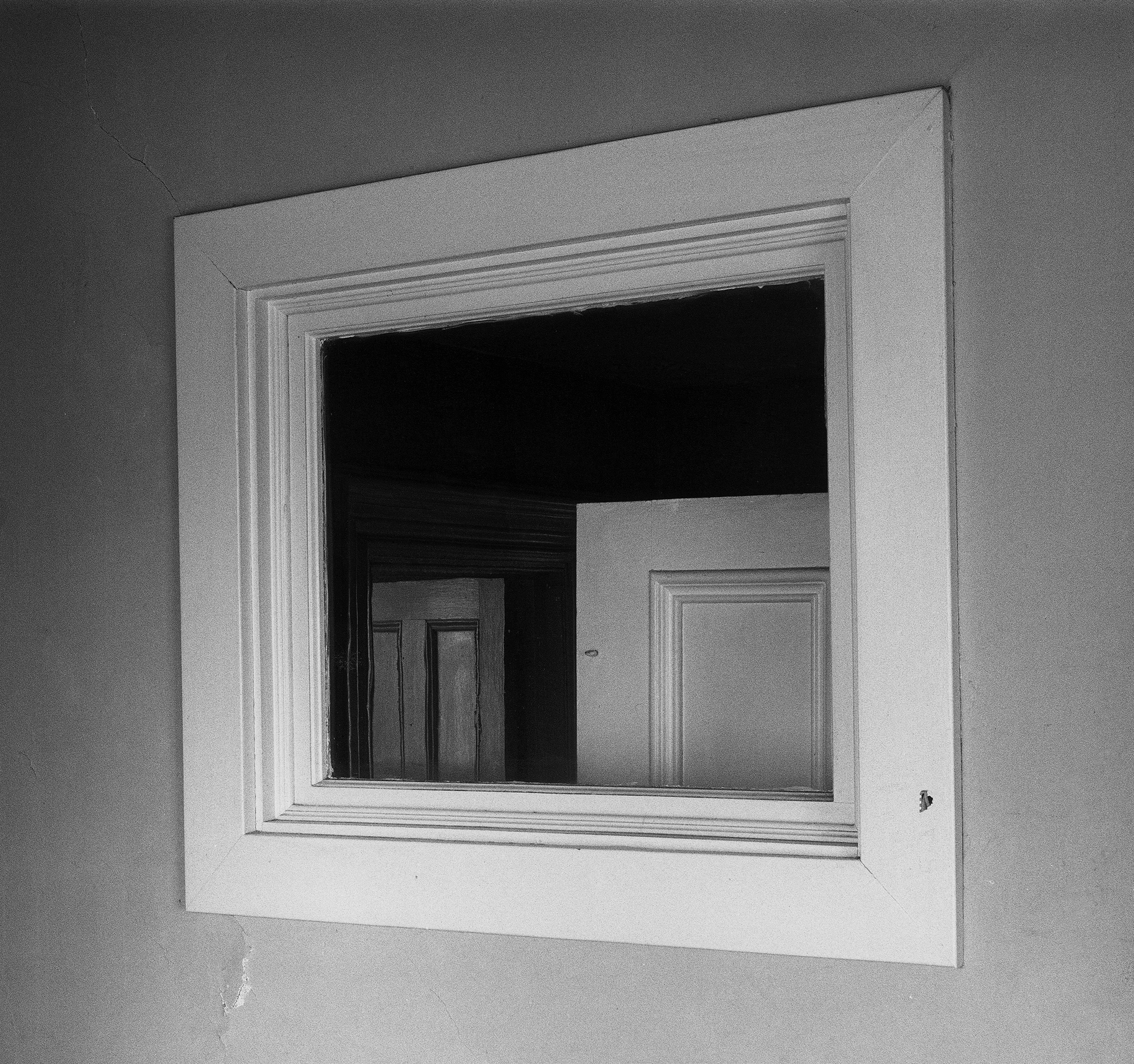

“Aren’t we wasting time?” you say. “It’s dark and cold. We’ve got to find her.” The officers gather their things. One makes a call on his portable radio while the other says a few encouraging words. Dixon goes to the window, and you see his reflection looking back at you.

Throughout the night you field phone calls, talk to volunteers, investigators. The police come in streams of navy blue, mussing your rugs and filling your living room with their authority. You want to do more than sit by the phone, more than watch them huddle and plan. “But you are needed here,” they say. “What if she comes home? You should be here, just in case.”

So you sit at the kitchen table with stacks of photographs and wait. You finger the one of her as a baby, asleep in Dixon’s arms, and you think of the way she often cried in the night, the way you tried everything to please her, and how she always came around for Dixon instead. Even last night she had a nightmare, and you couldn’t console her. Dixon shuffled into her room after you, pulled her into his arms, and whispered to her. You backed off and watched as he wooed her to sleep. Standing in the doorway, just five feet from her, you felt so far away. Why always him? Why not you?

“It’s like that with fathers and daughters,” he said when he joined you in bed. “It doesn’t reflect how she feels about you.” And you thought about your own father, your fragmented memories of coarse whiskers and leather belts. Even after you remind yourself of your mother leaving, of him struggling to raise you on his own, you always return to how he failed. “It isn’t always like that,” you said, but Dixon was already asleep.

You flip through a set of recent snapshots: the end of summer, the last trip to the beach. Anna and Dixon, Dixon and Anna. And then you see an image of yourself, just out of focus, the mother just out of reach. You place the photograph at the bottom of the stack and breathe. Keep it together, keep it together, keep together.

They ask you to record your thoughts in a notebook, as this might unveil a clue to her whereabouts that you hadn’t thought important before. So you pick up a pen and try to think of what matters.

She matters, you write. She mattered for years before she was even born. Dixon wanted babies. “A house full of light,” he said. But you didn’t see it that way. You grew up in a house full of children who didn’t shine, who didn’t have much more than walls to hold them. A full house never made sense to you. Why turn your marriage inside out with constant demands and worries over square meals and school shoes? One child, maybe, but several would only wear you out, take you down, just like your mother.

You didn’t voice your resistance to Dixon; instead you spent years hiding your birth-control pills in the bottom of your purse, increasing your responsibilities at work and accepting promotions while the house echoed and Dixon worked in the yard, even in other people’s yards. He has a way with growing things, can make anyone’s garden both useful and captivating.

He has a way with her, you write.

In the morning you give an interview to the local television station. Dixon sits beside you, looks down at his hands while a reporter asks you to recall details: age, height, weight, last seen heading down Forest Street. “She loves toffee,” you say. “And the ocean. She loves the way it always moves, even while we’re sleeping.”

When you stop, when you remember your fever and rest your head in your hands, Dixon stands and thanks the reporter, walks her to the door. “She’s been ill,” you hear him say. “She just needs some time to rest.”

“Of course. I’m so sorry,” the reporter says before Dixon closes the door behind her.

Later you watch her transform your scattered details into a cohesive plea for awareness, for reports of the slightest clues.

“Time is not on her side,” she says, looking into the camera, right at you.

Days later you both take polygraphs. You ride in the detective’s van through the daylit streets where neighbors go on with their lives. They go to school, or to work. They rake their yards while you face ominous questions that don’t make sense. “Do you know where your daughter is?” “Where was your husband at 3:20?” “Is your husband aggressive?” “How about you — do you lose your temper?”

This last one you can answer with certainty. “Yes,” you say. “Yes, I do.”

Before you had Anna, there was a morning every month when you would return to bed and Dixon would crawl back under the blankets with you, kiss your belly, and tell you he was sorry, as if he were failing you. But it was you who flunked each time, your body empty of the child he prayed for.

Dixon’s apologies filled your home. After a year they became too much. Finally the morning came when, just before he pulled back the blankets, you bolted from the bed, shoved him so hard you heard his head smack the wall. Then you grabbed the phone and held it like a rock over your shoulder.

“One more ‘I’m sorry,’ one more time, and I’ll give you something to be sorry for — you hear me? You understand me, Dixon?”

He stood facing you, astonished by your aggression. There would be other times, but that first one caught you both off guard. You started to shake, and he took the phone from your hand and placed it back on the nightstand. He took you in his arms and said nothing while you cried. You hate to cry when you mean to scream.

Four months later you were pregnant with Anna.

“With Anna, ma’am; do you lose your temper with Anna?” the detective asks.

“No,” you say, “never with Anna.”

Over the next few weeks you distribute fliers around your neighborhood and town. Your friends and neighbors help. They bring casseroles to your kitchen and take stacks of fliers away with them. No one really knows what to say, not even you.

The Center for Missing and Exploited Children advertises her face nationally. She is everywhere now. Her face shines from the backside of coupons for dry cleaning, from cards that read: “Have you seen me? Call 1-800-THE-LOST: More than 95 children featured have been safely returned.”

You wonder: How many unsafely returned?

At night you pretend to sleep. Dixon isn’t sleeping either. You both lie there, waiting for something. A miracle? Forgiveness? Relief? He tries to hold you, but you inch away, closer to the edge of the bed, where you can be alone in your suffering.

You know he blames himself, and you let him. During the moments when you’re not feeling guilty, you blame him, too, for forgetting. But you should have known he might forget. Think of the time he left you waiting outside the theater — eight months pregnant. He dropped you off for the matinee and went home to unload the pickup. The movie came and went, and you waited in the dusk afterward, watching the parking lot. Then your insides were lit with pain. Too soon, you thought. Back inside the theater, you asked them to call an ambulance. “It isn’t time yet,” you whispered, holding your belly and sliding to the floor. “We’re not ready for you.” Dixon finally showed up, just in time to see them close you inside the ambulance.

But he’d never failed her since.

Months go by. Still, for a split second each afternoon, you think she will be there, waiting. Sometimes you give in and walk to the bus stop, imagining she will come to you like she used to, lisping and giggling. You can feel her breath in your hair, her girlish hug around your neck. But then the bus arrives, and from a distance you watch the children emerge. The driver is new, but the children are the same.

Jess jumps off the bottom step. She was the last to talk to Anna. Now she takes her mother’s hand. They walk a few feet, and then Kate kneels beside Jess, who talks excitedly — about what, you cannot hear; something that has nothing to do with Anna, although months ago it might have. They were close, like sisters, both with long, dark curls. These days Jess wears her hair short, like her mother. They see you eyeing them, so you smile and wave and head back toward the house.

They are distant; everyone is distant now.

You begin to feel how alone you are. Dixon is drinking. He spends his days inside, searching for her over the Internet, his nights absorbing Scotch by the fireplace, trying to warm the chill inside him. You wear short sleeves to compensate for the temperature he keeps the house.

You move next to him on the couch, take a sip of his Scotch, and ask if he might want to see a movie, have dinner out — anything to distract you both. After months of searching every inch of dirt, every foot of pavement in a twenty-mile radius, he refuses to leave your home.

“Those woods,” he says, “they can swallow you. I won’t go out there, not again, not even if you paid me.”

You realize he means it, and your blood turns hot, shoots through your body to the palms of your hands. You hold back the urge to slap him; instead you touch his face and look right into his eyes for the first time since he told you she was missing.

“You know someone took her,” you say. “You know that, don’t you?”

He takes you by the wrist and shoves you away, calls you “heartless.” “You don’t know that,” he says. “You don’t fucking know.”

“We can’t do this, Dixon. We can’t go on like this,” you say, and you force yourself to walk away, leaving him clutching his glass, his own liquid truth.

He comes to you later, kisses you like he used to, and you let him. Your body, thin and greedy, acts without your even thinking. Your hands are quick to guide him inside, and together you move like waves, one after the other, while you still feel alone.

Finally you go back to work. It’s been months since you balanced other people’s accounts, but the numbers come easily. You are thankful for the break between morning and night, the hours when you can sit in your office and contemplate nothing but figures. You want to stay longer, take refuge from the grief that has overwhelmed Dixon, but you know you shouldn’t.

At home he will be waiting by the window, watching for Anna the way he does, and when he sees you, he will look past you for his little ghost. When he realizes, his face will crumble in a way you cannot watch anymore. His is a perilous hope, the kind that might catch fire and burn if he moves just a hair in the wrong direction.

On the drive home, you pray for him. It used to be you prayed for Anna — for her return, her life — and you still do in the late hours when sleep circles you, slips its fingers through your hair, painting it white; but in the daytime you pray for Dixon. You pray he will let go of his little ghost long enough to realize that you go on. You go on longer than you ever dreamed, beyond the walls, the woods — like an avenue you think should end.

By summer you know you’ve lost her. The hope you had tucked away is gone, and you cannot even recall her movements, just the frozen image of her seven-year-old smile, framed and hanging in your hallway. You call in sick and shut yourself in your bedroom. While you fade in and out of sleep, you try to re-create the morning she came to you, kissed you goodbye, and said, “I hope you feel better, Momma.” This very room, these very sheets. Dixon stood in the doorway and hurried her. “Come on, angel. We have to go.”

She was his child, his light. You try not to think of how you cried for weeks when you found out you were pregnant with her. Mothers shouldn’t regret becoming mothers.

But it isn’t hard to see you did it for him, and maybe she knew it too. He was the first to hold her. He made it to the hospital in time to stand beside you in the room while they numbed you, then cut you open to save her from the umbilical cord. Your temperature was dropping, so they let you see her for only a second before he carried her away. You didn’t feel cold at all, but they kept layering one blanket after another on top of you while you asked, “Is she OK? Is my baby OK?” Hours passed before you could finally nurse her. Dixon held her in the meantime.

He is downstairs, always downstairs now. Lost in the loss of her. It seems there is nothing left of him for you, nothing left of the man you loved so much. There is only anger and distance between you now. But you want to take back every painful moment. You want him to come back from where he’s gone. You want his forgiveness.

What can you do? You could go to him, take him in your arms and plead for a break in the darkness. But you worry he won’t see you, and the fear paralyzes you.

You could leave — now’s your chance. Just leave behind the grief, the dance with hope. In time you could wash away the memories, replacing them with trivial moments, unremarkable days, and nights in which sleep would come. Only the dreams would remind you.

The door opens, and Dixon pauses in the doorway, wrapped in a blanket, hesitant, as if asking for permission to enter. Your heartbeat quickens. He looks at you and waits. You close your eyes and touch your hand to your heart. When you open your eyes, you see that he understands, and you pull back the covers, inviting him to join you. He comes to you, shedding the blanket, and you hold him. He is shaking. You stroke his back, and his body softens in your arms. How thin he has become. You want to say something to him, something loving and promising, something about how together you will make it. But what could you say that would make any of this right? Instead you let the moment speak for itself, his body against yours, a tangible beginning.