My wife, Rayleen, got it into her head that our luck died with our dog, Buddy. “We buried it in a hole in the ground” is how she put it.

Buddy was chasing the garbage truck, like he had every Tuesday of the world, when Sissy Simmons backed her Mustang out of her driveway and ran him over flat. Thank God Rayleen wasn’t home. I had enough trouble trying to calm Sissy down, because she felt just awful, which was Christian of her, considering the kind of dog Buddy was. I know for a fact he killed Sissy’s cat, Muffin, and I don’t know how many others. And on account of Buddy, the mailman wouldn’t deliver to our end of Locust, so we all had to troop to the P.O. to collect our mail. Like I said, there was no reason Sissy Simmons should have felt all that bad about it, but she did. And it did her credit.

“Rayleen isn’t ever going to forgive me,” Sissy wailed.

There wasn’t much I could say on that score, on account of she probably wouldn’t.

When Rayleen did come home, there was hell to pay. If Buddy had died in his sleep in his own armchair in our living room, Rayleen would have found somebody to be mad at. Rayleen’s not one of your “no-fault” people. She doesn’t fit into this new age of “It’s all good!” She’s keeping score; she’s laying blame; she has lists. She’s still mad at the Koreans. She blames them for her daddy’s drinking problem, which led directly to a powerful lot of misery in the Powell house.

So the first thing Rayleen did when she heard about Buddy was to run over to the Simmonses’ with a big old rake and thrash every last bloom off of Sissy’s hydrangeas that grow in tubs all along her front porch. Sissy kept her head down and didn’t come outside, which was smart. I just watched Rayleen from our front yard and never tried to stop her. What would have been the point? And besides, I thought it might make Sissy feel a little better if she paid a price. She set store by those hydrangeas. By the time Rayleen came trailing home, she’d wore herself out. Back at the Simmonses’, Sissy was over being sad about Buddy and was mad as a hornet. Take a step back from it, and you’ll see both women were better off.

Then Rayleen locked herself in the bathroom. She does that when she might be going to cry. So I went out to the backyard and started digging a hole to bury Buddy. I picked a spot under the big pecan tree where he used to lay up with his prizes — rib bones, dead cats, whatever he’d come across in his ramblings and taken a shine to.

Maybe, with me being so honest about Buddy, you’re wondering why we were so crazy about him. I can only say Buddy was totally committed to the life of a dog. There was nothing human about him, so nobody blamed him when he acted like a dog. We could never have kept him tied up, fenced in — any of the things people do with their dogs these days. I’d have run him over myself before I would have done that.

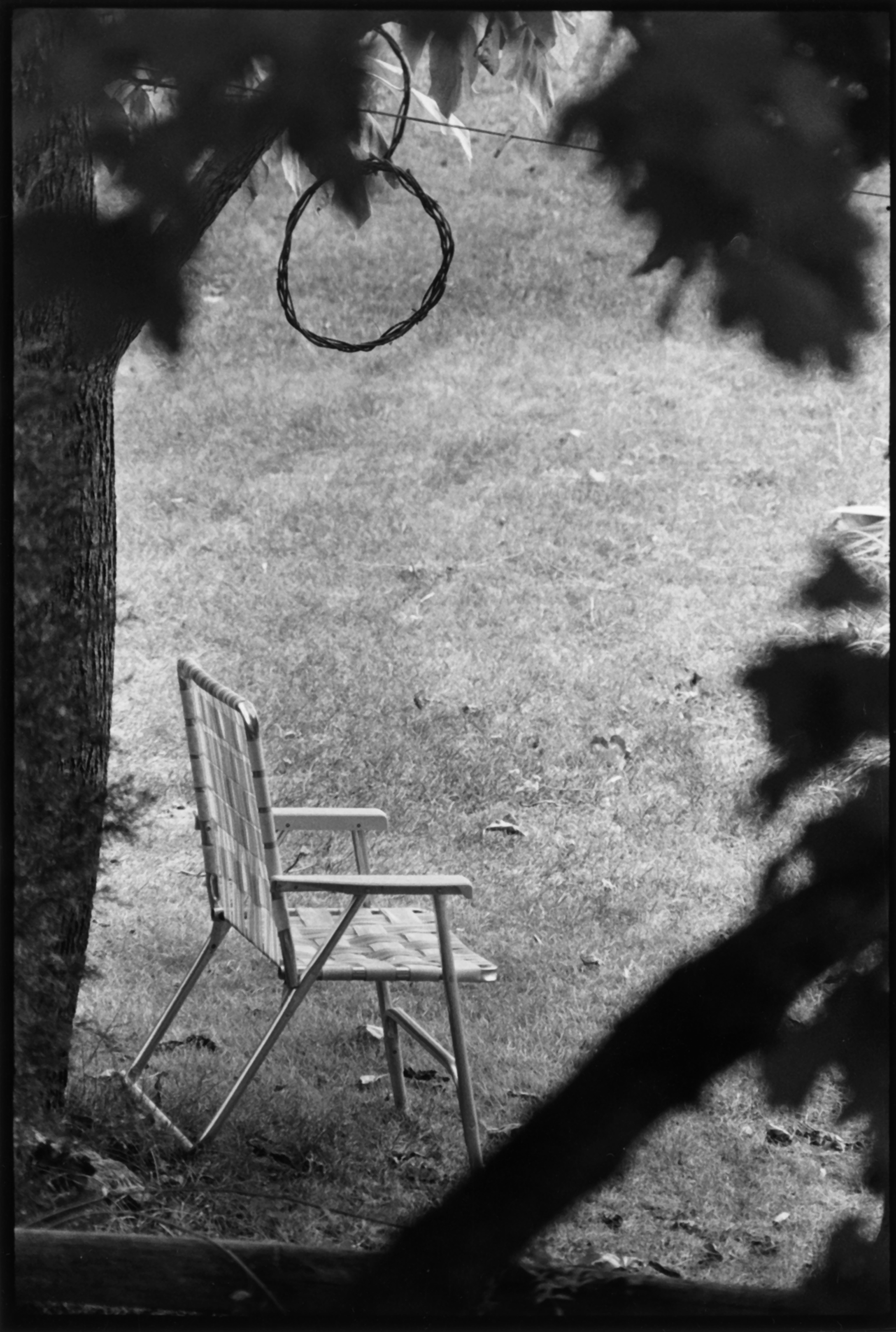

The hole was nearly four feet deep when Rayleen came out of the house. Buddy’s body, wrapped in an old army blanket, was lying at the base of the tree, near Rayleen’s lawn chair. She sat down in the chair and watched me dig. This chair is one of those low wooden ones that looks like it’s made out of picket fencing. Rayleen likes to sit there in the evening and watch the sky.

Finally I backed away from my hole and said, “That’ll do it.”

“You didn’t build a damn house, R.L. You dug a hole in the ground.”

I let that one go. You try digging a hole big enough for a bull terrier, then say it’s not an accomplishment. I picked up Buddy and climbed in my hole with him and laid him down. Rayleen threw in a couple of his skinned tennis balls and a well-gnawed rib bone. “He’d want these with him,” she said, and then she picked up a shovel, and we started filling in the grave.

It was almost dark when we were done. I went in the house and got us a couple of beers. When I’d finished my beer, I lay back and looked up into the pecan’s branches. There’s not much for two people to say to one another when they’re just done burying their dog. We’d had Buddy since the second year of our marriage. He was twelve years old. We’d gotten him for the kids we just naturally thought we’d be having but never did. We don’t even talk about that anymore. You might say, “You could adopt.” No, we can’t. Rayleen’s a stickler for the real thing, and I respect her for it. Most people say how they want the real thing or nothing at all, the absolute best or forget it. But then you tell them, “Sorry, looks like it’s going to be nothing,” and, oh, right away they take whatever you’re offering, because to them something is better than nothing. Not Rayleen. She’ll do without. And she won’t gripe.

Anyway, Rayleen’s little brother, Tom, who we ended up raising, had provided us with all the aggravation and heartbreak of a kid of our own. But Buddy was ours. To show you how everybody else thought so too: Buddy rode in the town’s centennial parade last year, right up beside Bob Sweeney on the firetruck. Well, when the firetruck passed, everybody watching from the curb said, “There goes Buddy Kopel.”

“Is there more beer?” Rayleen asked.

“No.”

“Let’s go out for Mexican.”

Mexican food is Rayleen’s answer to all life’s disappointments, disasters, and just plain confusions. We go out for Mexican after funerals, big fights, bad weather, and to celebrate occasions when you know you should feel happy and grateful, but you don’t. One way or another, we could single-handedly support La Casa del Matador.

But to get to the tie-in between Buddy’s death and Rayleen’s and my bout with bad luck: Coming back from La Casa del Matador that night, the Pontiac gave out. We had to leave it on the shoulder and walk home. For the two minutes I wasn’t thinking about the money it was going to cost me, I kind of enjoyed the walk. The moon was headed for full, and we were still tight from the pitcher of margaritas we’d had at dinner. There just for a moment, I forgot about Buddy.

But the next morning was rough. Hung over and bereaved, we weren’t making much conversation. I had to call Tom, Rayleen’s brother, for a lift out to the job he and I were working — a wildcat drilling operation that had been a lifesaver but probably wouldn’t last much longer. When I called, I got Tom’s girlfriend, who told me that Tom had been arrested the night before in Dallas on a weapons charge.

Now, here in the state of Texas it’s not real easy to offend the powers that be on the subject of firearms, so I figured Tom must have done something seriously stupid. We don’t own a gun ourselves. I’d be afraid to live in the same house with Rayleen and a gun. She does good enough with rakes or whatever’s at hand. I’ll just mention, too, that her father shot himself, and her other brother died in what people always call “the hunting accident.”

“Tom stayed over in Dallas,” I said to Rayleen, casual-like, after I hung up. “I’m going to have to take the truck.” The truck was on its last go-round. The only reason I hadn’t junked it was that I’d had it since I was seventeen.

Rayleen was reading the classifieds and just nodded. I grabbed my lunch and kissed her forehead, and I was out the door.

When I drove up to the house that night, Rayleen was sitting in her chair under the tree. She didn’t get up. I was used to Rayleen and Buddy meeting me at the car, so from the start nothing felt right. Rayleen looked pinched and small. You’d have to know her to understand how different from normal that is. Rayleen’s a small woman, but she puts off so much heat and talks so fast you get this impression you’re talking with two or three people. Little as she is, she takes up a lot of space. Normally. Now she was sitting in her chair, about as big as a thirteen-year-old girl.

I sat down beside her. We never even disturbed the song a mockingbird was singing in the willows down by the creek.

“Tom’s in jail,” Rayleen said.

“I know.”

“I know you know. Candy said she told you this morning.”

“I didn’t want you to have to face that this morning. I reckoned Tom could find his own way out for once.”

“I told him to call up that bimbo for bail.”

“Good,” I said, but I was surprised at the way Rayleen was taking it. Touch a hair on Tom’s worthless head, and generally you got Rayleen right down your throat.

“I had Steve go out and get the Pontiac,” Rayleen said. “He’s going to call later tonight when he’s had a chance to look at it.”

“Thanks.”

We didn’t say anything for a while. The mockingbird sang on. I averted my eyes from the mound of dirt Buddy was lying under.

“Rayleen? Are you all right?” Of course, I knew she wasn’t all right, but I had to say something. “Rayleen?”

“R.L., my dog died, my brother’s in jail, my car won’t run, and I’m a childless orphan. And I got a husband so dumb he asks me am I all right.”

“I know,” I said. “I wouldn’t worry if you had a knife in your teeth and were headed for Dallas to spring Tom from jail. But I worry about you when you’re quiet like this. It’s not like you.”

“I guess I’ve got enough sense to know when my luck’s run out,” she said.

So, there it was, out in the open. The Subject.

My father-in-law, Clinton Powell, had raised up his children to believe in his own personal God, Luck. He’d used it to explain every sorry result of his own selfish ways. When he decided his luck was gone for good, he was true to his creed and shot himself. Well, that put a stop to the run on his luck, but it was just the beginning for Rayleen and Tom and their mama. Anyway, it was a subject I didn’t have any patience with.

“Your luck ran out years ago, Rayleen. Like you said, your daddy killed himself, your mama died in the nuthouse, you married beneath yourself, and you ain’t got chick nor child. Why should you think your luck’s run out now?”

“It’s just something I can feel, is all.”

“Bullshit.”

“No, I’m telling you, R.L., when we buried Buddy, we buried our luck. You dug the hole, and we filled it in. It’s gone. You’ll know it after a while. You’ll see I’m right.”

“First off, Rayleen, I don’t believe in luck. How can I believe in something I never had? In my whole life the only thing that could be called ‘lucky’ that ever happened to me is you. And if I did believe in luck, I’d have to resent you saying that mine died with a dog. People’s luck don’t live inside dogs.”

Rayleen didn’t answer. I saw a tear roll down her cheek. If I had believed in luck, that tear would have sunk me sure.

Later that night Steve called about the car. It had thrown a rod. I had to wonder for a minute was Rayleen maybe right. But the next minute I had to figure some way to pay for the repairs. Rayleen and I don’t have a savings account, and we don’t have credit cards, and the people we know mostly don’t have those things either. We’re just ordinary working people in a part of the country that nothing ever trickled down to. When things get rough, when something’s going to cost us, we have to dig down deep. We work an extra shift, if we can get one; the wives go to work at a mini-mart; we borrow from a relative; or we just do without. I was lucky enough to get an extra shift.

And I was glad to be gone from the house, to tell you the truth, the way Rayleen was acting. There’s nothing more discouraging than trying to cheer up somebody who’s set herself against being happy. Nights when I’d get in from my late shift, I’d find her slumped on the davenport watching television. I’d ask her what she was thinking, and she’d say, “Nothing.” That was easy to believe, because her face would be blank as a doll’s. Normally her face is as changeable as Texas weather. Go ahead and ask somebody to describe Rayleen, and they’ll tell you all kinds of things about how she’s likely to act in a given situation, but press them to tell you what she looks like, and they’ll have trouble. The reason is she overpowers her looks with her personality. Always has. But if you were looking at a snapshot of her, you’d see she has dark eyes, that her mouth is wide, and that her nose turns up. Her hair has a crazy mind of its own. (What nobody knows but me, and maybe Tom, is that she has to comb it out with a wire dog brush — it’s that thick.) Her top teeth are a little prominent. I didn’t notice that myself until this bout of bad luck when she got so quiet. It’s like when you turn the volume down on your TV and just watch the picture, you’re way more noticing of how people look than when you can hear what they’re saying. I also saw she has a little web of broken veins on her thigh. I’d never seen that before. I don’t know what all else I might have seen if Rayleen’s luck had stayed gone any longer than it did.

Anyway, I’d ask her did she want some ice cream, and she’d shake her head, and I’d ask could I bring her a beer, and she’d say no. I’d get me something and sit down next to her and put my arm around her, and she’d go right on watching TV. It was like I had my arm around a fence post. One night I asked would she like me to go see about some pups that Merlin Jenkins’s bitch Rhonda had just whelped. Merlin raises hunting dogs, and his Rhonda is famous in this vicinity. When Merlin gets a litter, he keeps back one or two pups for pets. But Rayleen said you couldn’t buy luck off Merlin Jenkins. Well, I never said you could, and the way Rayleen was acting had started to hurt my feelings, so I dropped it.

The summer wore on, but Rayleen’s mood didn’t change. In fact, you couldn’t really call it a “mood” anymore. One night when I came home from my late shift and tried to wake her, she never even stirred, so I covered her with the afghan her crazy, dead mother made, and I went in the kitchen and sat down at the table with a beer. I didn’t turn on the light. Out the window there was enough moonlight for me to see that Rayleen had whitewashed some rocks and put them around Buddy’s grave. I thought about how I could maybe get Rayleen to believe in her luck again. I couldn’t make any more money than I was making working two shifts. I couldn’t straighten old Tom out. Truth to tell, Tom is trash, and trash is trash — it don’t change nothing if it’s related to you. So what was I going to do to put the heart back into that woman asleep in the other room? I couldn’t make her rich or resurrect her dog. I drank two beers, ran through my options, and came up as dry as the last well I’d worked on.

I lined up my beer bottles on the drainboard and went to bed. I only had three hours to sleep, so I got right on it.

Before I ran out of steam, I’d made the money to pay for the car plus another five hundred bucks. Maybe you couldn’t buy luck, but I figured with five hundred I might be able to facilitate it some.

The first morning I had off, I slept in. When I woke, the bedroom was hot, and I lay there feeling as tired as I had when I’d fallen into bed. My mouth was dry, and I had that bad, scary feeling I’d had all the time when I was little: that everything was wrong and the world was dangerous. When I married Rayleen, I’d stopped having that feeling, but now it was back, and for good reason: everything was wrong, and the world was dangerous. Some people may be lulled by what they see on TV into thinking that the world is made up of happy families living in neat, pretty houses with great outdoor scenery and beer trucks barreling along country roads. They might think that if their lives don’t work out, there’s some new, other life waiting for them to live it. They go around saying, “If I die,” instead of, “When I die.” Well, not me. My people never lived like that. I don’t say I wouldn’t enjoy being able to forget all this from time to time, and I will say that for years Rayleen had stopped me brooding over it, and what I knew that morning was I really needed her to be able to do it again.

I pulled on my jeans and went in the kitchen. The sink was full of dirty dishes, and there wasn’t any coffee made. There wasn’t but a heel left in the bread sack sitting on the table. I could hear the TV going in the living room. Rayleen never used to watch TV. I could be watching a football game, and she’d come in the room and just snap it off. Except for some old movies she liked to watch over and over, she almost never turned it on. Now it was never off. I’d gotten so I hated the goddamn thing.

Rayleen was watching The Oprah Winfrey Show and folding laundry, and she didn’t stop doing either of these things when I came in the room, so I says, sarcastic-like, “And a good morning to you.”

“Lynette called. Jim’s left her for that waitress he was seeing down in Jasper. And she said she’d seen Candy at the laundromat, and Candy told her that Tom’s getting out of jail in a couple of weeks.”

She said all this in a flat tone of voice. Lynette was her best friend. Jim and I have worked together on and off all our lives. Rayleen went over to the ironing board and tested the iron with a wet finger, then started ironing one of my blue work shirts. Here was a woman who hadn’t cooked a hot meal or washed a dish in weeks, and she was an ironing fool. “Since when do you iron my work shirts?” I said. I could have asked since when did she iron, period.

She shrugged and went to ironing that shirt like I was maybe going to wear it with a tuxedo.

“You’re acting like a schizoid Stepford wife; do you know that, Rayleen? I wish you could see how stupid you look since you stopped being yourself. And since you’re not yourself, which you aren’t, who in the hell do you think you are?” I was fighting a strong urge to take that ironing board and smash out the front window with it.

I come from a long line of wife beaters, and that’s a fact. I’m not bragging, but I’m not exactly apologizing for it either. Most men have wanted to hit a woman at some time. If you haven’t hit one, I put it to you that you never felt pushed enough, or you never lived long enough with the humiliation of knowing how fucked everything is, how different the real world is from the one you were told about. You don’t know what a chump you’ve been, or how long you’ve been one. But the person who knows all this about you is your wife, and for reasons of her own she’s likely to point it out to you. And if she does this enough, you’ll hit her eventually. If things are the way I said.

Well, knowing this about myself is one of the reasons I married Rayleen. Rayleen’s never taken anything off anybody. I’d always known better than to hit her. First off, she was always so busy. There was always something she was doing, something she meant to have. I’ve been grateful most of my life just to be among the things that Rayleen Powell has wanted in this world. And second, Rayleen’s strong, and she can be mean, so from the beginning I was never even tempted. And knowing that, I felt nicer.

But watching her iron that shirt that day, I wasn’t feeling nice. This woman I kept calling by Rayleen’s name scarcely even looked familiar to me. It was like a woman I didn’t know — and didn’t even particularly like — had pushed her way into our house. In some part of my sleep-deprived brain I blamed her for my Rayleen being gone. I felt like I had to show this imposter who was boss, so I said, “Could I get some coffee? Would that be too goddamn much to ask?”

She put down the iron and went into the kitchen, and I heard her run water in the kettle. I followed her and sat down at the table. When she was putting the kettle on the stove, I saw her brush her hair off her forehead in that way Rayleen has, which for some reason always about breaks my heart. I was feeling crazy. I hadn’t had four hours of sleep a night since Buddy died, when I’d gone on double shifts, and the sadness that had settled in the house like some kind of poisonous dust was making it harder and harder for me to breathe.

“Come sit here on my knee a minute,” I said.

She came over and sat down on my knee like it was an unexploded bomb. She stared straight ahead at the wall clock. I put my hand on the back of her neck and pulled her head to mine to kiss her. She kept her neck stiff as a rod.

When I had her there, so stiff, so unyielding — when she wouldn’t even kiss me — I couldn’t leave it go. I struggled with her to make her kiss me, to try and make her love me again, and then I pulled her down to the floor and under the table.

Now, I’d never forced myself on Rayleen before. I’d never had a reason to and probably wouldn’t have even if I’d thought I had a reason. If you’d asked me, I’d have said I never in a million years would have done what I did. I certainly wasn’t studying on love. Not sex either, because I never enjoyed a minute of it.

Well, at the end of it we were clear across the floor from the table; Rayleen’s head was slam up against the freezer full of okra she’d put up, just for me; she doesn’t eat it. (That thought went through my deranged mind at the time.) Rayleen didn’t really fight me; if she had, I don’t think it could have happened, tired as I was. Like I said, she’s a strong woman.

We lay there up against the freezer for a minute. Finally I came to my senses enough to hear the kettle screaming. When I lurched to my feet to turn it off, Rayleen streaked out the back door. I watched her from the window over the sink and saw her plunge down into the willows and out of sight. She was wearing her mother’s ratty, old bathrobe — all she’d worn in weeks. I could hear my own raggedy breathing and the kettle still complaining.

That night Lynette called and said Rayleen was staying with her, that Rayleen said not to even call her, or she’d call the cops. I said fine. I’d loused everything up so bad, what else was I going to say?

The only good thing about any of this was that, just for a second, I’d seen the old Rayleen. When I saw her leaving out the back door, that had been my Rayleen. The Stepford Rayleen would have stayed. She’d have laid flat on her back on the kitchen floor and waited for me to do it again. That’s what I’d hated about her.

I went back on double shifts. I didn’t care how tired I got; I couldn’t get tired enough to stop thinking about what had happened, what I’d done. I avoided the kitchen and ate all my meals at La Casa del Matador. I cursed my luck. I started to remind myself of Rayleen’s daddy.

Even I saw Rayleen had been right to leave me. Our luck had run out. She said we’d buried it with Buddy, so every night when I came home, dead tired and dead drunk, I’d go out in the yard and sit in Rayleen’s chair and stare at the grave surrounded by white rocks that gleamed in the moonlight. One night, when I was really drunk, I got a shovel and tried to dig our luck up. I stumbled around out there for an hour, cut through the leather of my boot with the shovel and bruised my foot. Then I limped in and passed out on the davenport.

I’d hear news about Rayleen from Lynette’s husband, Jim. He’d moved in with his waitress friend, Sherry, and Lynette had taken up with an old boyfriend, Delmar, but Jim and Lynette still talked on the phone. I heard that Rayleen never left the house — which was driving Lynette nuts, since she was trying to use Delmar to make Jim jealous enough to dump Sherry and come home. Jim just laughed it off. Jim would go home when he felt like it. Or he wouldn’t. Either way, he wasn’t worried about Delmar.

I was afraid Rayleen was going to kill herself like her daddy had, or go nuts like her mama had done. Maybe she’d go nuts first, then kill herself. But how nuts is nuts? A grown man out in his backyard at two in the morning, hunting his luck with a shovel — was he nuts? Seemed to me like he might be.

I found out then where I stood with people here in town. To let you know: you’d have had to bend at the waist to hand me a quarter — which was interesting to me, because I’d been so careful my whole life to be pleasant to folks. I’d thought of myself as a likable guy. But there was no confusion as to who the heavy was when it came to our breakup. They were calling my wife — who hadn’t been on speaking terms with lots of them for years on account of one thing or another — “poor little Rayleen.” I could have understood if they knew what I’d done, but they didn’t. She never even told Lynette. If she had, Jim would have known, because those two told each other everything. So just exactly what was it that everyone thought I’d done that made them feel so sorry for Rayleen and think I was such an SOB? Had I killed my own dog? Had I thrown the rod on Rayleen’s Pontiac? Had I put her brother in jail? Had I stuffed her luck in a sack and thrown it off a train trestle? I wouldn’t get anywhere trying to figure that out.

One night I was sitting at the bar at the Matador drinking by myself when up comes Mike Polk. Now, Rayleen just hates Mike Polk, and vice versa. One time Mike made some remark about Rayleen’s daddy’s suicide, and that same night Rayleen poured sugar in the gas tank of his GTO and left a note on his windshield that read, “Sweets to the sweet.” Of course he couldn’t prove Rayleen had done it, but everyone knew she had. Anyway, Polk came right up to me at the Matador and said, “I hope you’re proud of yourself. Driving a nice little girl like Rayleen out of her own home.”

Now, nobody missed Rayleen worse than me. And nobody thinks more of her. But she was never a “nice little girl.” Of course, I knew what he meant by that part about “her own home.” Crazy and mean as they mostly were, the Powells have lived in these parts a hundred years or more. In the end Rayleen’s daddy had sold off all the family property to cover his debts — all except for the house. That had gone to Rayleen’s mama, and then after they carted her off, we’d moved into it to raise Tom. When Rayleen’s mama died, Rayleen had inherited it. So when Mike Polk said I’d run Rayleen out of her home, what he really meant was I’d run her out of her house — her birthright. There I was, the town nobody — brought up by a woman with a bad reputation in the first trailer park to blight Titus County — living like he was somebody in the Powell house. I’ll grant you, it looked bad.

I told Jim to tell Lynette to tell Rayleen that I’d vacate the house if she wanted to come home. I knew that Lynette was praying Rayleen would say yes, but she didn’t.

Just when things were as bad as I thought they could get, they got worse. I came home one night and found Tom in the kitchen frying himself up some of my eggs.

“So, honcho,” he says to me — the man who’d supported him for seven years — “how they hanging?”

I ignored him and got the last beer out of the fridge. He put his eggs on a plate and smothered them with ketchup. I didn’t say anything. Without Rayleen in the picture, it was more Tom’s house than mine. Mike Polk had made me more than a little aware of that.

“Does Rayleen know you’re here?” I asked.

“No, I just got in. You’re the first person I’ve seen; downtown’s dead.”

“Were you expecting a homecoming parade?”

He just smirked.

“Rayleen’s staying over at Lynette’s,” I said.

He nodded and went on shoveling eggs into his mouth. “Yeah,” he said, “Candy told me. I hear ol’ Rayleen left you flat.”

I could see the part he was interested in was how the breakup had put me in a bad position. He hadn’t given thought one to his sister.

“How come you aren’t staying with Candy?”

“Just felt like checking out the old homestead,” he said.

“If you’re staying, take your old room. I got to get some sleep.” And I left him mopping up his eggs with the last piece of bread in the house.

The next day I told Jim to tell Lynette to tell Rayleen that her brother was home.

Tom didn’t waste a moment taking over the place. I never knew who’d be there when I got home from work, or how many. His creepy friends and their women were crawling all over the place. Their music — if that’s what you want to call it — blared out the windows. They gawked at me when I walked down the hall to the bathroom, which was usually occupied and locked. I put up with it because I reckoned that our neighbors would make my case to Rayleen better than me.

One day at work Jim says to me, “Rayleen wants to know can’t you straighten Tom out. The neighbors are calling her.”

“Tell her I can’t do a thing with him.”

I went on waiting for Rayleen to rescue me from Tom. I worked, and when I wasn’t working, I drank. I just came back to the house to sleep.

By this time it was fall. On Halloween Tom and his friends all took off to some Dallas nightclub to threaten one another with chains and knives and show off their tattoos. I turned off all the lights so the kids would think nobody was home. I didn’t have anything for trick-or-treaters except beer and corn chips. I treated myself to both while I sat in the kitchen so I could keep an eye on my truck and the trash cans, in case any of the little vandals got wild or destructive. (Kids do that nowadays. Nothing is what it had been — not Halloween, not anything.) The world was getting uglier every day, seemed like to me, and my nasty little secret was I liked it that way. I bought armfuls of tabloids at the 7-Eleven. I listened to talk radio in the truck. I couldn’t get enough bad news. Not like there was any kind of shortage: wars everywhere you looked, the oceans dying, AIDS sweeping the junior highs, child molesters popping up in every family. Give me a story about some couple taking turns beating up their granny and their kids and setting the dog on fire, and I was set for the night. I finally felt in tune with the world: it stank, and so did I.

I was digging in the sack at my feet for another beer and keeping an eye on the window when I heard a scratching sound at the door behind me. I didn’t get up because the beer in my hand was my umpteenth of the night, and I didn’t trust my legs. Anyway, I figured when I swiveled in my chair and yelled at the juvenile delinquents, I’d scare the piss out of them.

When the door creaked open, I turned and saw only one kid, a teenager by the size of him, dressed like a ninja and holding one of those long knives of theirs. I hollered, but he didn’t turn and run like I’d thought he would; he just kept coming straight at me. It was way too crazy for me to make heads or tails out of, drunk as I was and with my mind already crammed full of the horrible images I’d been filling it with for weeks. I could have moved, but I didn’t. It came to me, all of a sudden, that what I was seeing was my Fate, the Fate I had coming to me, and I knew it would be wrong to fight it or try to run from it either. I needed to take it like a man. The kid slipped around behind me and put the edge of the knife to my throat. You see that phrase in the tabloids all the time: “He held a knife to the victim’s throat.” You read that, and you go on reading, but a knife to the throat — your throat — is something you don’t get past in a hurry. I’ll tell you that for free: it sobers you up real quick!

The kid pulled my head back by my hair and then — kissed me! Even with a knife to my throat I knew the taste of my wife’s kiss.

“Do you think I’ll kill you, R.L.? What are the odds?”

“Jesus God, Rayleen! I don’t know. But before you do anything, let me just say, first, I’m too drunk to stop you. And second, I’m so glad it’s you, I don’t really care.”

She let the knife clatter onto the table. It was an old white enamel table; if it had been a wooden one, I know she’d have stuck the knife point in so I could watch it quiver. She sank down in a chair and took the black mask from her face. “Aren’t you going to offer me a beer?”

I reached down and got a beer out of the sack and opened it. My hands were shaking. I could still feel the knife’s edge on my throat.

“We’re even,” she said. (I’d have said she was way ahead.) “Anyway,” she went on, calm as you please, “I’ve decided to come back to you.”

I was guzzling my beer with a shaking hand. “This is kind of sudden. Why now?”

“Let’s just say that I don’t have the heart to leave you to Tom’s tender mercies. Lord, R.L., why in hell didn’t you just throw him out?”

“Well, with you gone, it’s more his house than mine. Least that’s what most people around here seem to think.”

“When did I ever care about what most people think? It’s our house, R.L., and we’ve let Tom live here way too long as it is. But Tom’s not the reason I’m back. I’ve been thinking a whole lot about luck since I left, and believe you me, I’ve had plenty of time to do it. Lynette put me out on her lumpy couch when she let that awful Delmar James move in, and she moved the TV into their bedroom. I’ve had nothing to do but think. Talk about luck: those are two people who need it, because God knows they don’t have anything else going for them.”

Rayleen was talking even faster than usual, like she hadn’t talked in weeks, like she’d been storing it up.

“Anyway,” she said, “I came to the conclusion that you were right: we never had any luck to begin with. But then I thought, hell, it isn’t like luck will be the first thing you and I have done without. And I’m guessing it won’t be the last.” She took a long swig of her beer and put it down beside the knife. “But what you have to know and remember, R.L., is that I’m not quite as tough as you think I am. Turns out I’m not even as tough as I thought I was. And you can’t make me tough by getting mean as the world yourself, like you did that day.”

“I was out of my head, Rayleen.”

“Spare me the insanity defense. What I hate, R.L. — what you need to understand — is that it’s the way everything happens that gets to me. I mean, the exact moment Sissy ran Buddy over, I was drifting around in Vern’s Variety buying rickrack and lipstick and feeling so . . . normal. Just like when Daddy killed himself, I was defrosting the fridge and making deviled eggs. And when they called to say that Mama was gone, remember, I was hanging curtains in the kitchen.”

I remembered. I’d been holding the stepladder and fondling her leg.

“I’ve never once had what my aunts used to call ‘a feeling’ when something was wrong. I never once knew my saddle was about to slip out from under me. So now nothing scares me worse than an ordinary day. And that’s the problem: If you’re scared of bridges, you can stay off them; if you’re afraid of snakes, you can stay out of the woods. But what do you do when you’re afraid of an ordinary day?”

I didn’t know. I’d been scared every day of my life.

We were both quiet for a while. “Tom’ll be back pretty soon,” I said, looking at the clock over the stove.

“Not for long, he won’t,” Rayleen said, picking up the knife to test its edge. “That sorry son of a bitch is hitting the road. Tonight.”

That sounded like my Rayleen.

And never mind all that’s happened, I like to think someday we’ll be old, sitting out on our porch together, rocking, and Rayleen will have a shotgun across her knees, and I’ll be saying, “Easy now; it ain’t time to shoot — yet.” That’s how I think it’s going to turn out.