As a college junior I interned with Planned Parenthood. Saturday mornings at 6:30 A.M., I would open the clinic door to a line of women already waiting outside in the cold. They had come, some from hundreds of miles away, for abortions. My job was to take their medical histories, answer their questions in a legally mandated counseling session, and provide emotional support while the doctor performed the procedure. Most women held my hand, cried, and told me stories of bad relationships, poverty, and loss. Others stared at the ceiling while I hovered nearby. One patient turned to me in the middle of her abortion and said, “Your compassion is overwhelming.”

Sometimes I would encounter patients by chance in public. I always felt nervous when this happened, because I was bound by confidentiality not to initiate contact with them. Once I spent an entire lifeguarding class treading water next to a former patient, and we never spoke. I ran into another woman at a swanky art exhibit; she acknowledged me with a slow nod from across the room. Drunk students often came up to me at keg parties to list all the reasons they’d chosen not to have a baby, as though they were seeking some sort of absolution. I felt differently about them than I had at the clinic, where they’d been scared and vulnerable. In the outside world, I thought of them as careless for having gotten pregnant and selfish for having ended their pregnancies.

Today I have an eleven-week-old son, and I rock, soothe, and nurse him all day long. Sometimes I think of how I judged those women who terminated their pregnancies. They were wise to realize that they could not take on this difficult job. They made the best decision they could.

Elizabeth O’Brien

Inverness, California

When I was living in Berkeley, California, I returned home from vacation to find that someone had broken into my apartment. My television was gone, along with most of my household appliances, and garbage and cigarette butts were scattered on the carpet. I rushed into my bedroom, where I was relieved to discover that my computer and my guitar remained untouched. Then I saw two feet poking out from underneath the covers on my bed.

I should have called the cops, but I wasn’t thinking clearly, and instead I nudged the burglar awake and asked him to leave.

“Yeah, could you give me a few minutes?” he said.

I recognized him as a homeless — and probably mentally ill — person I’d seen on the streets.

“Sure, I guess,” I said, and I left the room, feeling as though I were the one intruding.

When I came back, he was trying to steal my DVDs. I snatched them from his hands and escorted him out. Minutes later I noticed him attempting to break into my neighbor’s apartment, at which point I called the police.

After the man was arrested, an officer asked me to identify him for the police report. I was nervous: would the homeless man seek revenge on me for ratting him out? But he looked harmless with his hands cuffed behind his back and his face expressionless. Our eyes met, and I turned away.

“That’s him,” I said.

Later I imagined how the homeless man had come to be asleep in my apartment: Perhaps he’d been ready to make his getaway with an armload of my possessions when he saw my bed. It had been so long since he’d slept in one, nestled beneath real sheets. He couldn’t resist.

Hans Oh

Glendale, California

The plane was full of tourists flying from Delhi to Jaipur, a popular vacation spot in India. My eyes were riveted by one passenger in particular: demure smile, twinkling eyes, auburn hair, bright blue scarf. After the plane had landed, she walked from one end of the tiny airport to the other, as if searching for someone. When she passed me, I asked, “Is anything wrong?”

A car was supposed to pick her up, she said, but it wasn’t there, and she couldn’t remember the name of her hotel. I told her she could come to mine and make some calls: there were only three hotels in town. It turned out we were staying in the same one, and we had dinner together that night. I found out she was from Germany and would return there after her vacation.

Eight months later I was in Frankfurt for a conference and had a free evening, so I called her. She picked me up from my hotel, and we had dinner at her place. I ended up staying the night. After I returned home to India, we phoned and wrote each other often, and I kept her photo on my desk. But the relationship ended, in part because of the distance between us.

Five years later I missed a connection at a London airport and ordered an espresso while I waited. I looked up from the first sip to see her twinkling eyes and auburn hair. We embraced, and she told me she worked in England now. I abandoned my flight and took her to my favorite Westminster restaurant. Over dessert, I asked, “Do you ever wear scarves anymore?” She searched in her bag, found a scarf, and placed it around her neck. The same bright blue scarf. I could have wept.

Manish Nandy

Reston, Virginia

At the supermarket I got in line behind an elderly man who was unloading cans of dog food onto the checkout belt. I had recently acquired a puppy, so I asked what kind of dog he had. He looked at me with red-rimmed eyes and said he had a big German shepherd named Coco, who was his best friend. He’d lost his wife a year before to cancer, and just that morning he’d heard that his oldest daughter had cancer too. (I figured she was about my age.) His eyes brimmed, but no tears fell. I expressed my sympathy, and he mumbled thanks, paid for the dog food, and left, looking as sad as any person I had ever seen. I resolved that if he was still in the parking lot when I got outside, I would talk to him.

He was just getting into his old Toyota pickup.

His name is Floyd, and he and I have met for breakfast every week or two since then. Coco died two winters ago, so Floyd is on his own now. I call him several times a week to see how he’s doing. “Everything’s quiet,” he often tells me. We agree that quiet is good.

Before he retired, Floyd worked in textiles and metal fabrication, except during World War II, when he was a gunner with the 30th Infantry Division. He arrived on Omaha Beach eight days after D-day (there were still bodies washing up) and made it through the Battle of the Bulge. He has outlived two wives, one daughter, several dogs, and any number of friends.

Now eighty-seven, Floyd is stooped and has only one working eye and few teeth. He bathes on Sunday nights, the same night he does laundry. He owns a little Cape Cod house off a busy street, cooks for himself (“My mother taught me everything”), tends his garden, mends what’s broken, and worries about what will happen to his things “if” he dies.

Ours is an unlikely friendship. We always have breakfast at the same diner and never have to look at the menu. Floyd talks; I listen. He tells me about his childhood, the war, his jobs, his friends who’ve died recently, and what’s happening on his favorite TV shows. He often complains that he doesn’t have any ambition, but he’s mending his back stairs, and last fall he planted a hundred spring bulbs. He says he’s going to live forever. I’ve learned not to argue.

Margaret Boyer Mann

Hamden, Connecticut

Throughout high school I dated a studious and religious girl named Myra. I was her opposite — an alcoholic juvenile delinquent — but we fell in love despite our differences, or maybe because of them.

At seventeen I was sent to reform school, and two years after that I was arrested for burglary and did time in a maximum-security prison. Near the end of my sentence, I was placed in pre-parole forestry camp, from which I managed to sneak away. I stole a car, drove to my old neighborhood, and arranged a meeting with Myra at a lake several blocks from her home. When I told her of my escape and my plans to go to California, her eyes filled with tears, and she asked if she could come with me. I surprised myself by saying no; I didn’t want to drag her into my mess.

I spent the next decade in and out of prison for crimes ranging from drunk and disorderly conduct to armed robbery. Then, at thirty-one, I married, fathered two sons, and settled into a sober and law-abiding existence.

Eleven years later I was working at the baggage-department counter of the Greyhound bus depot when one of the drivers dropped off a purse that had been left on his bus. That afternoon, a woman came to inquire about the purse. It was Myra.

“Andy?” she stammered.

“Good to see you, Myra,” I said, and I walked around the counter and lifted her into the air. As we hugged, I detected a strong scent of alcohol. Her hair was mussed, her makeup was smeared, and deep worry lines surrounded her eyes.

Later an old friend filled me in on Myra’s downhill slide: A longtime alcoholic, she had been divorced twice and arrested a couple of times for drunk driving. She had lost custody of her three children.

When I reflect on the way our situations have reversed, I wonder how her life might have turned out if she had run away with me on that summer day twenty-five years ago.

Name Withheld

In the back seat of my car, my three-year-old daughter is crying because she has dropped the cracker she was eating, and I have no more to give her. Her high-pitched wails shatter my nerves. Beside her, my nine-month-old son is also in tears: frightened by his sister’s crying, tired of being confined to his car seat, and distressed that he is separated from me. His breath comes in hiccups, and his sweaty hair clings to his forehead.

It’s been a long day. I want to go home, drink a glass of wine, shower, and get some sleep, but instead I will spend the evening cooking dinner, giving bottles, cutting up food, cleaning up potty-training accidents, breaking up fights over toys, holding one crying child, then the other — sometimes both — reading stories, singing songs, and putting my children to bed. Then, after their bedroom doors are closed, my husband will turn to me wanting to make love. I feel irritated at the thought.

To drown out the sound of my children’s misery, I turn up the volume on the CD I’m listening to. It was given to me by a co-worker I have a crush on. Lately his company at work is all I have to look forward to. I tell myself that I’m attracted to him only because my life is so hard right now; that what I’m feeling is not love but a desire for escape. But this crush is threatening to turn into something more — if only for me — and, as I sit at the red light, listening to his favorite music and the cries of my children, I know I must get over him. It’s been fun, but it isn’t real, and the risks are unfathomable.

The light turns green, and I’m preparing to drive off when a white car in the next lane catches my eye. It’s my co-worker, waiting to turn left. My heart jumps, and for a second I imagine I could unbuckle my seat belt, open my door, and slip into his passenger seat, leaving my car and my children’s tears behind.

Then the driver behind me beeps his horn, and I accelerate through the intersection toward home. By the time I pull into my driveway, the kids have fallen asleep, but the CD plays on, and I’m still thinking of my co-worker in the car beside me, and the impossible possibility of going with him.

Name Withheld

In 1969 I was an infantryman in Vietnam. Our company was stationed near Saigon and patrolled the jungles just north of the city. We also set up nighttime ambushes in the peanut fields beside the main highway, near foot trails that disappeared into the surrounding jungle. More often than not, these missions were uneventful, uncomfortable, and wet. During monsoon season, you could set your watch by the slate gray clouds that rolled in just before dark and dumped sheets of rain.

On one such evening my squad of seven was assigned to set up an ambush beside a trail that wrapped around the base of a hill jutting from the jungle’s edge. The rest of the platoon — about thirty men — was camped on top of the hill. Rain dripping from our helmets, my squad and I waited for the cover of darkness so we could take up our ambush position behind a large log. Suddenly the crack of close-range gunfire broke the soggy monotony. One of us had come face to face with a Viet Cong who’d appeared out of the jungle. Just like in a B-grade western, the U.S. soldier had beaten the Vietnamese to the draw. With our position exposed, we abandoned the ambush plan and pulled back to the top of the hill with the rest of the platoon for the night.

At daybreak a column of North Vietnamese regular-army soldiers crossed the highway and snaked its way down the trail beside our hillside position. I estimated more than five hundred men, at least a battalion. We were close enough to hear them talking as they passed by. When they came upon their fallen comrade on the trail where we had left him, the column halted and sat down in front of us for twenty minutes. Impossibly outnumbered, we didn’t so much as twitch a muscle the entire time. After they’d disappeared into the jungle, we called in air strikes, but they were gone.

Our commanding officers were livid that we had not attacked. (Body counts were considered a sign of progress in that war.) Silver stars and purple hearts could have been won. Our platoon sergeant was sent away in shame. But I believe our platoon lived that day because that Vietnamese soldier — probably an advance runner — had happened across our path and gotten shot. Had we set up the ambush, that enemy battalion would have come right over the top of our position.

Thirty-nine years later I still think of that soldier’s crumpled body with a strange mix of gratitude and guilt. His death saved us.

Bill Wertz

West Harrison, Indiana

It’s a long drive to the airport at 5:30 in the morning, and there’s not much on the radio but songs that bore me and news I’d rather not know about. As usual, a fantasy takes over: I’m sitting on the plane and look up to see you walking down the aisle. Why you after more than twenty years? We spend the next few hours reminiscing, catching up, apologizing, forgiving, and telling truths that we weren’t able to tell back then.

In real life I get to the gate, sit down, and look around. I have a game I play of guessing what people are like by looking at their shoes. Across from me is a pair of men’s sandals, good chestnut leather, worn over tan socks. A personality is starting to take shape: Casual, a seasoned traveler. Cotton pants. New York Times. Well-worn leather briefcase. Fine hands. A face that looks like yours might at sixty or so. I look away. My heart pounds. No, it’s not you. I’m making it up.

A four-year-old girl across from you asks you where you’re going. I strain my ears but can’t hear the answer. You show her that trick where it looks like you separate your thumb at the joint. Yes, it must be you.

I try to read, but I’m stealing glances your way. I should just go up to you and say, “Excuse me, but I think I know you.” No, it’s too much of a coincidence, and it’s only because I was thinking about you. This man could be anyone. A couple of times I shift my position as if I might get up, but I chicken out. Once, our eyes almost meet. You stand up and start to walk in my direction, but you change course. Are you thinking the same thing?

We board the same plane and fly. From where I’m sitting, it’s hard to investigate discreetly whether it’s you. We land, and everyone stands up. Passengers take out their cellphones. You are holding Car and Driver. It has to be you. I walk the long passageway with you right behind me. Turn around! I say to myself. But I don’t. Four years later I still don’t know why I watched you walk away, back into my past, where you belong.

Julie Orfirer

Ashfield, Massachusetts

As a female freshman in college, I volunteered at a group home near campus, assisting the boys there with their homework a few times a week. I became close with the five residents, aged twelve to fifteen, all of whom had been removed from abusive homes. I had grown up in a middle-class suburb, where I had been unaware of lives like theirs. By the end of the year, I’d changed my major from veterinary medicine to psychology-sociology. I wanted a career working with high-risk adolescents.

I graduated and got a series of jobs at detention centers and public schools. After six years, I went back to the same university to get my graduate degree. A woman in my program was volunteering at the group home where I had done my tutoring, and I asked her about the five youths I had worked with — in particular, Matthew, who I’d thought was bound to be successful. She said he had been convicted of rape and assault at the age of eighteen and was in prison. I was stunned and disappointed.

About a year after that conversation, I was walking to my car off campus late one night when I saw two tall figures coming my way. Other than them and me, the streets were deserted.

I turned off the sidewalk and walked between an old home and the strip mall where my car was parked. The two men split up: one came around the house in front of me, while the other followed behind. I tried to stay calm, but my stomach churned with fear. Then a parking-lot light above my car illuminated the face of the man approaching me. I recognized him immediately.

“Matthew,” I said, “it’s me, Rene,” and I went over and hugged him. He introduced me to his friend as his old tutor from years before. We laughed and chatted, and neither of us mentioned his time in prison. I got in my car and drove off, still trembling and astonished by my good luck.

R.R.

Bayfield, Colorado

I turned twenty-one in April, and by September I had dropped out of school, accumulated thousands of dollars in credit-card debt, and developed a drinking problem. Each morning I’d wake up in a foul mood, unable to conjure a single positive thought about my life.

It was around this time that I began to consider the dreaded possibility that I was gay. My straight friends were pressuring me to meet girls and get laid, but the thought of being with a woman horrified me, and, as a defense, I would get too drunk to perform, running up hundred-dollar bar tabs in the process.

I was a manager at a health club, and one afternoon a fellow manager and I were waiting in the corporate office’s lobby. On a bench across from us sat an attractive guy my age who was looking at me with a probing gaze. Feeling uncomfortable, I avoided making eye contact. After he’d left, I asked my fellow manager who he was.

“He’s a manager at another club,” he answered. “I’ve heard that he’s gay.”

I acted unfazed, but after I got home, I couldn’t stop thinking about that guy in the lobby and how he’d looked at me and made me feel: as if, for the first time, somebody had seen the real me and not the straight man I was struggling to be. In him I saw a different version of myself, the sort of person I could be, and I was both disgusted and exhilarated.

Since that afternoon I have come out to my family and close friends. I have been doing well in school, I am working toward getting my finances in order, and I have learned how to drink without going over the edge. Most important, I wake up every morning filled with a sense of possibility.

Luke A.

Sacramento, California

About a year after my twenty-year-old daughter’s death, I was still heartbroken. While she’d been ill, I’d prayed to God to take me instead. Then I was diagnosed with cancer. I got chemotherapy and radiation, and my daughter died.

On a dreary winter morning I was walking my two dogs in the park when I saw a middle-aged man with a mohawk haircut coming toward me. There was no one else in the park, and I felt vulnerable. My friends often comment on my tendency to attract strange people. I kept my eyes down, hoping this man wouldn’t talk to me.

When the man got close, he warned me about a section of tree trunk that was hanging dangerously over the path in the direction I was headed. There had been a windstorm, and many trees and limbs were down.

He told me that he was walking in the park because his youngest sister, a Canadian law-enforcement officer, had just been killed in a shootout, and he didn’t know what to do with himself. I told him about my daughter, and we talked about how sometimes grief is so deep it makes you want to lie down and die. We cried and hugged before we parted.

As I approached my car, I saw that the top section of a fig tree — the one he had warned me about — had fallen and lay splintered all over the path. If I hadn’t stopped to talk to him, I might have been there when it fell.

Name Withheld

At the age of fifty I was diagnosed with stage-IV melanoma and had two major surgeries that left me with huge scars. A divorcée, I expected to spend whatever life I had left alone. Who would want to enter into a new relationship with a cancer patient?

A few years later I went to my thirty-fifth high-school reunion, where I felt an immediate attraction to an old classmate named Jerry. He and I arranged a date, but I was worried about revealing my cancer and my scarred body to him.

On our second date I told Jerry my secret, and we talked about how cancer had affected both our lives: he had developed testicular cancer when he was only twenty-eight and had a scar running from beneath his breastbone to his groin. I had one scar in my lower groin, and another running from under my right scapula to just beneath my right breast.

On our third date Jerry and I showed each other our scars and kissed them.

It’s now many months later, and we no longer even notice our healed wounds. I feel lucky to have found a wonderful lover like Jerry. And to think: both of us almost didn’t go to our reunion.

Catherine Moyers

Los Angeles, California

I was waiting to renew my license at the Department of Motor Vehicles when a man about my age got in line behind me and began filling out a form.

“Is my hair gray?” he asked me.

“Don’t you ever look in the mirror?” I said.

“Yes, of course, but I think it has some brown in it too.”

“It’s gray,” I said.

We talked about the long line, the miserable weather, and the day’s news. I asked what kind of work he did, and he told me he was a writer. “What do you write?” I asked, hoping it wasn’t computer manuals or tax guides.

“Poetry, some satirical pieces, screenplays,” he said. “Norma, my wife, always proofread my work. She died three years ago, on our fifty-fifth anniversary.”

I told him my husband had died of cancer a year before. We’d been married for forty-eight years.

“So you know how it feels to come home to an empty house,” he said.

I liked this man, whose name was Dan. There was something sweet and ingratiating about his manner. We exchanged phone numbers, and though I later flunked the license exam, I left the DMV feeling more lighthearted than I had in years.

Dan called me a week later. “Are you the lady I met at the library?” he asked.

“Department of Motor Vehicles,” I corrected him.

He asked if he could come by the next day at three o’clock. I said of course. He arrived at 4:40, though he lived only five minutes away. “I couldn’t find your house,” he said. “My wife used to do the navigating.”

Something was amiss, but I was too intrigued to try to figure it out.

Dan and I began dating. He often forgot the times of movies and which days we were going out, and he was so perplexed by directions that I wound up being the designated driver. But his deadpan humor cracked me up, and soon we were making serious declarations of love. We learned that sex in our seventies could still be breathtaking.

One Wednesday afternoon, when we were leaving to go to a play, a woman of about forty pulled up in Dan’s driveway. “Dad!” she called.

“Karen, what are you doing here?” he asked.

“Your doctor appointment. I called you last night to remind you.”

Dan flushed with embarrassment. After introducing us, he told his daughter we had tickets for a play.

“Keep the appointment, Dan,” I said. “I’ll tell you about the play.”

After that Dan’s decline became precipitous. He would call me at nine in the morning and then again at 9:15, having forgotten that we’d spoken. One day on the phone he said, “I know I’m deeply in love with you, and my life has been wonderful since we met. But . . . I’ve forgotten your name.”

I made a joke out of it, teasing him with outlandish names: Magdala, Zahara, Charmain.

“My memory isn’t that bad,” he said, laughing. “I know your name starts with a P.”

“It’s Phyllis,” I said. “And I love you.”

After I hung up, I couldn’t stop crying.

Phyllis Rose Eisenberg

Van Nuys, California

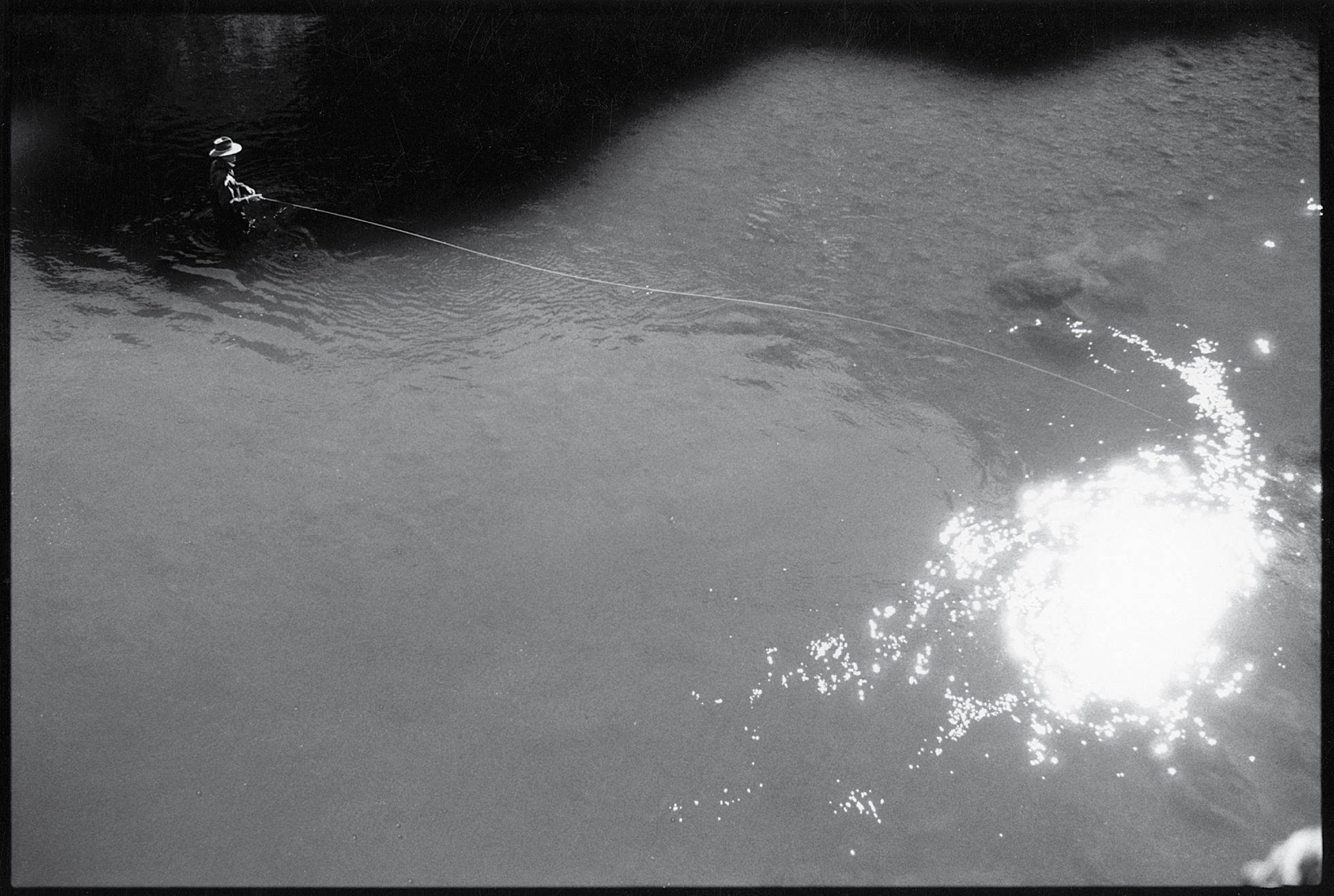

At midlife I’ve developed a fascination — all right, an obsession — with fly-fishing. I’m standing in the fly-tying aisle at a sporting-goods store when I hear a voice behind me say, “Be careful. This can become an addiction.”

“It already is,” I reply.

The voice belongs to a man nearly ten years my junior. His name is Jim, and as we discuss the finer points of fly tying and the majesty of trout, I notice that he limps. He explains that he has a debilitating disease and for the last few years hasn’t been able to do much fishing. When I tell him that my wife and I are heading to Montana on vacation, where I am sure to work in some fly-fishing, Jim is excited for me and asks if I would “mind” if he tied some flies for me to bring along.

What do you say to a complete stranger who volunteers to help you enjoy your vacation?

Jim and I exchange contact information, and a couple of weeks later he delivers to me fifteen hand-tied flies crafted to look like wasps, ants, minnows, and other bait. I am amazed by the quality and attention to detail. It must have taken him hours to make them. There’s also a four-page letter explaining how to fish each fly.

I catch so many fish using Jim’s flies that I want to show my appreciation. When I get back, I offer to take him fishing. He says he has fished only once in the past year, because of his illness, but he’d like to give it a try.

I pick him up on a breezy late-summer afternoon, and we fish for several hours in a small stream. From time to time Jim needs to stop to catch his breath. He shows me where to cast and often gives me one of his flies to tie on my line. When I change to another lure and try to hand his fly back to him, his response is always “It came off the end of your line, and it goes in your box.”

It’s some of the best trout fishing I have ever done. Around dinnertime we head home, stopping at a gas station along the way for Jim to get a drink. I wait in the car and think about how this day was supposed to be my gift to Jim, but instead he’s expanded my fly collection and my knowledge of fishing once more. He’s given me so much; what have I given him in return?

When I look up, I see Jim straining to make it back to the car. He can hardly walk. When I ask if he’s all right, he smiles and says, “I’ll feel this for a few days.”

Then it hits me: Because of his condition, he has been forced to accept the help and care of others. In me he’s found someone who needs his help. Maybe I’ve given him something after all.

Jeff Miller

Wausau, Wisconsin

I’d left behind my boyfriend, John, in Boston to go to graduate school in Illinois, but I wrote him every day, worried he would find someone new in my absence. Though I missed him, I was enjoying the respite from all the parties and weekend trips and sporting events he’d dragged me to. I was spending more time on things that nourished me: walks in the woods, needlework, foreign films.

When the graduate program became overwhelming, I dropped out, but I stayed in the small college town for a while, reluctant to give up the picturesque life I had there. Finally, encouraged by John’s emotional pleas to come back to him, I decided to return to Boston.

I slid into a bus seat in St. Louis, feeling like a failure and not sure how I felt about John. I loved his deep brown eyes and his playfulness and his moral integrity. He had the courage to speak the truth when others were afraid. So why wasn’t I more eager to get back to him?

I changed buses in New York City, and a studious-looking boy sat down next to me. He was going to graduate school in Boston, he said, and so was his fiancée. They enjoyed the same movies, took long walks in the woods together, and told each other everything. My relationship with John seemed inadequate by comparison. I told the boy about my confusion, and he advised me to pay attention to how I felt the moment I saw John in the bus station.

When I got off in Boston, John was waiting on a bench, looking tired and sloppy. His hair was too long, his shirttails hung out, and when he greeted me, he seemed awkward and unsure. I felt the same way.

At the apartment we argued: I wanted to wait tables for a while; John thought I should use my degree to become a professional (something he wasn’t doing). He was beginning to seem less moral and more judgmental.

In the days that followed, he watched sports and got together with his friends. I tagged along, but something was missing. The boy on the bus — I didn’t even know his name — had taught me to pay attention to what I felt.

A year later I moved back to Illinois alone.

Lynne D.

Carbondale, Illinois

I had been bumped off a flight and gotten a free plane ticket from my home in California to anywhere in the continental U.S. or Puerto Rico. I wanted to go somewhere I’d never been, but I was mostly unemployed with little money, so I went to Boston to visit friends.

Despite the challenges I’d faced as the child of immigrants, I’d excelled in school, so I decided to make a special trip to see the Harvard campus. Once I got there I was underwhelmed. This is it? I thought.

I struck up a conversation with a professor in the school of education. When I described my undergraduate work in the field of immigration studies, her eyes lit up: a close colleague of hers was looking for a Spanish-speaking research assistant who lived in California to help with a study of immigrant children.

Soon I was returning to the campus to interview for my dream job. Everything my potential employer described was related to my personal experience and academic field. I couldn’t believe I was going to get paid to do this work.

My future boss said that before I’d called her, she’d been sitting in her office thinking, Where am I going to get a Spanish-speaking research assistant who lives in California? You never know what’s just around the corner.

Dafney Blanca Dabach

Albany, California

I’m a single mom, and my ex-husband sometimes “forgets” to pay child support, so I budget carefully. I brew all my coffee at home, eat leftovers for lunch, and go to the library rather than the bookstore. The Sunday paper is a rare treat.

One dark, icy Sunday when my ex had the kids, I grabbed the St. Paul paper instead of the Minneapolis one, and I came across an article about “sober houses” in St. Paul. Alongside was a picture of a man I hadn’t seen in nearly a decade.

Jack looked older and sadder, but still handsome. When he and I had worked together, he’d been upbeat and quick to offer words of encouragement when my alcoholic soon-to-be-ex-husband had battled with me through our children. The article said that Jack was in Narcotics Anonymous himself, wrestling with a longtime addiction to heroin. In the decade since I’d last seen him, he’d tried to kill himself and was now holding on to his sobriety with a white-knuckle grip, knowing the alternative was death.

On impulse I sent an e-mail to the newspaper reporter, asking him to forward it to Jack. In the message I expressed my gratitude for the kindness he’d shown when we’d worked together, and I said that I was glad he hadn’t succeeded in killing himself. It was only after I’d clicked SEND that I wondered whether I wanted Jack to have my e-mail address.

Jack and I exchanged a number of soul-searching e-mails, some of which made me uncomfortable. He couldn’t understand why I had contacted him if I didn’t want to go out with him. I was afraid of opening up to another addict. After a couple of months we stopped communicating. I wondered if my e-mail had done more harm than good.

The following summer I was returning from lunch with a group of co-workers when Jack rolled by on his bicycle, head down. He was healthy, tan, and muscular, with tattoos coiling up both his arms. But he still looked sad.

Liz H.

Twin Cities, Minnesota

In 1974 my husband, our two-year-old son, and I were living in central New Jersey, and I was feeling out of place and unhappy. I blamed my husband’s commute for ruining our family life. After a round of marriage counseling, I asked him to try to get transferred. A month later he announced that he had accepted a new position — in Birmingham, Alabama.

This wasn’t what I’d had in mind. For a Northern girl like me, the thought of living in the Deep South was scary.

Nevertheless we leased an apartment and proceeded to pack up our belongings. The moving van would take two weeks to get there, so we had to stay in a hotel in the meantime. Around the end of the first week we found a New York–style deli where we could get some familiar food. As we sat waiting for our meal in the noisy restaurant, I was feeling overwhelmed by the enormity of the move, the isolation from friends and family, and the challenges of marriage and motherhood. Giving no explanation, I got up and ran outside.

Across the street was a low stone wall, and I sat down on it and began to sob. An older man came jogging around the corner. Seeing my posture and tears, he slowed down and said, in a soft Southern drawl, “Isn’t this a beautiful fall evening? This weather is perfect. Just look up at that sky.” He touched me lightly on the shoulder, then moved on. That’s all. But his touch and suggestion to “look up” brought me out of my misery and back into the world. It was a lovely evening (it was snowing back in New Jersey), and this city, despite its strangeness, was home to many good, caring people. I would find my place in it.

Jane Kirsch

Wayne, Pennsylvania

I have a list of work assignments to take care of, but I promised my teenage son this morning I’d call the DMV to ask a question about his driving test. Dialing the number listed in the phone book, I get a recording with twelve options. I have to replay the message three times to absorb them all and twice more to select from the next list. Then comes the music: an orchestrated version of Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven.” Twenty-five minutes pass. I could have walked the six blocks to the DMV office in the time I’ve waited. Finally I hear a voice: “California Department of Motor Vehicles. This is Kathy speaking. How may I assist you?”

“Yes, I’m calling about the ID requirements. What do you need to take a driver’s test?”

“Where are you calling from?” she asks.

“Where am I calling from? Right here in town,” I reply.

“What county, sir?”

“Plumas County. Where are you?”

“We’re in a centrally located office, sir. I’ll take your question and relay it to your county office, and they’ll call you back within forty-eight hours.”

“You’re kidding me. What’s your name again?”

“Kathy.”

“Well, Kathy, I’ve waited on the phone for half an hour to ask one simple question, and you’re telling me I’ve got to wait another forty-eight hours to get the answer? This is absurd! I could have walked —”

“I’m sorry, sir. Is there anything else I can assist you with?”

Determined to get a human response out of her, I press on: “Look, Kathy, you must see the humor in this whole thing. I mean, where exactly are you?”

“Our office is located in Campbell, sir.”

“I know Campbell. Isn’t it along Highway 17 en route to Santa Cruz?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Do they still call that stretch of highway ‘Blood Alley’?”

“Yes. It’s worse than ever.”

“You know what I used to do? I used to cut class in the sixties and hitchhike past Campbell to Santa Cruz and pick up girls.”

“Oh, really?” she says.

“Yes, really. By the way, my name is David, but back then I was known as Willie. I had my first kiss in Santa Cruz, underneath the boardwalk. Got so carried away that I fell over backward onto the sand. The girl thought I was an idiot.” Pause. “Kathy? You still there?”

“Yeah. So that was you, Willie?”

David van Winkle

Portola, California

At thirty-seven I had a decent job, good friends, and a deep-seated fear of commitment. But I was struggling to overcome my fear so I could find a husband.

One balmy August night a friend and I made plans for a girls’ night out. We were supposed to be enjoying each other’s company, but we knew we were both on the prowl for men. As we entered a smoky bar, my attention was caught by a dark-haired man nursing a beer. I gave him several enticing looks while we were there, but at the end of the night he downed his drink and left without a backward glance.

I was so taken with this man that I returned the next evening hoping to see him again. And see him I did. Exactly two weeks later, he and I stood before a justice of the peace.

After another two weeks, my new husband was on the run to Mexico with my jewelry and credit card. I stayed up late that night drinking bourbon, chain-smoking, and trolling the Internet for information about him. I discovered that he was a convicted felon on probation for having impersonated a peace officer in a neighboring county. I also discovered that he had gotten married before in Las Vegas — and never divorced.

I contacted his probation officer and retained a lawyer to have our marriage annulled. Meanwhile my “ex” turned himself in to his hometown police. The last I checked, his probation had been revoked, and he was doing time.

I should be furious with him, but I’m not. I think I needed this experience to force me to confront my fears about relationships. I needed to fall in love, get married, be abandoned, and survive.

Name Withheld

I was ten years old and living in Buffalo, New York, when the Yankees played the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1960 World Series. I was a diehard Yankees fan, and our teacher allowed us to bring a television to class to watch the seventh and final game of the series. In the ninth inning, the Pirates’ second baseman, Bill Mazeroski, hit a home run to beat the Yankees and win the World Series. I felt as if I’d been punched in the stomach, and I cried all the way home.

Over the years, I thought of that loss almost any time Pittsburgh was mentioned. Once, I saw a Major League Baseball commercial featuring past highlights, among them a shot of a triumphant Mazeroski rounding the bases, doffing his hat and waving his arms. Suddenly I was ten years old again.

I now live in Anchorage, Alaska, and retired ballplayers sometimes come here during the summer to play exhibition old-timers’ games. Years ago I was crossing a field near the ballpark an hour before one such game when I saw a man sitting in a folding chair near a batting cage. It was Mazeroski, older and thicker but still recognizable as the demon of 1960. I had to speak to him.

I came right to the point: “When I was ten years old, you broke my heart, you son of a bitch.”

He gave a sly grin and replied, “You and ten thousand others, and I’ve heard from every last one of you.”

Nelson Hubbell

Anchorage, Alaska