In 1974, when Chapel Hill, North Carolina, half-jokingly referred to itself as “the Berkeley of the South,” I was teaching at the university there and had bought part-interest in the Community Bookstore, which stocked natural foods and alternative books. The store was a beacon to travelers crisscrossing the U.S. in homemade campers and VW buses, as well as to locals living a bohemian lifestyle. (At the time, The Sun rented office space in a little yellow house across the street.)

The store’s owner, Richard, grew his beard long and folded it back in on itself to keep it out of the way and out of his bowl of granola or brown rice. He sat on a tall stool behind a glass case crowded with bulk foods. I helped customers in the evenings and on weekends with books on alternative energy, natural healing, and Eastern religions. Then we cleared some shelves in another room, and I opened a yarn business. From there I could hear Richard at his big, black adding machine, cranking out numbers and carrying on conversations with customers.

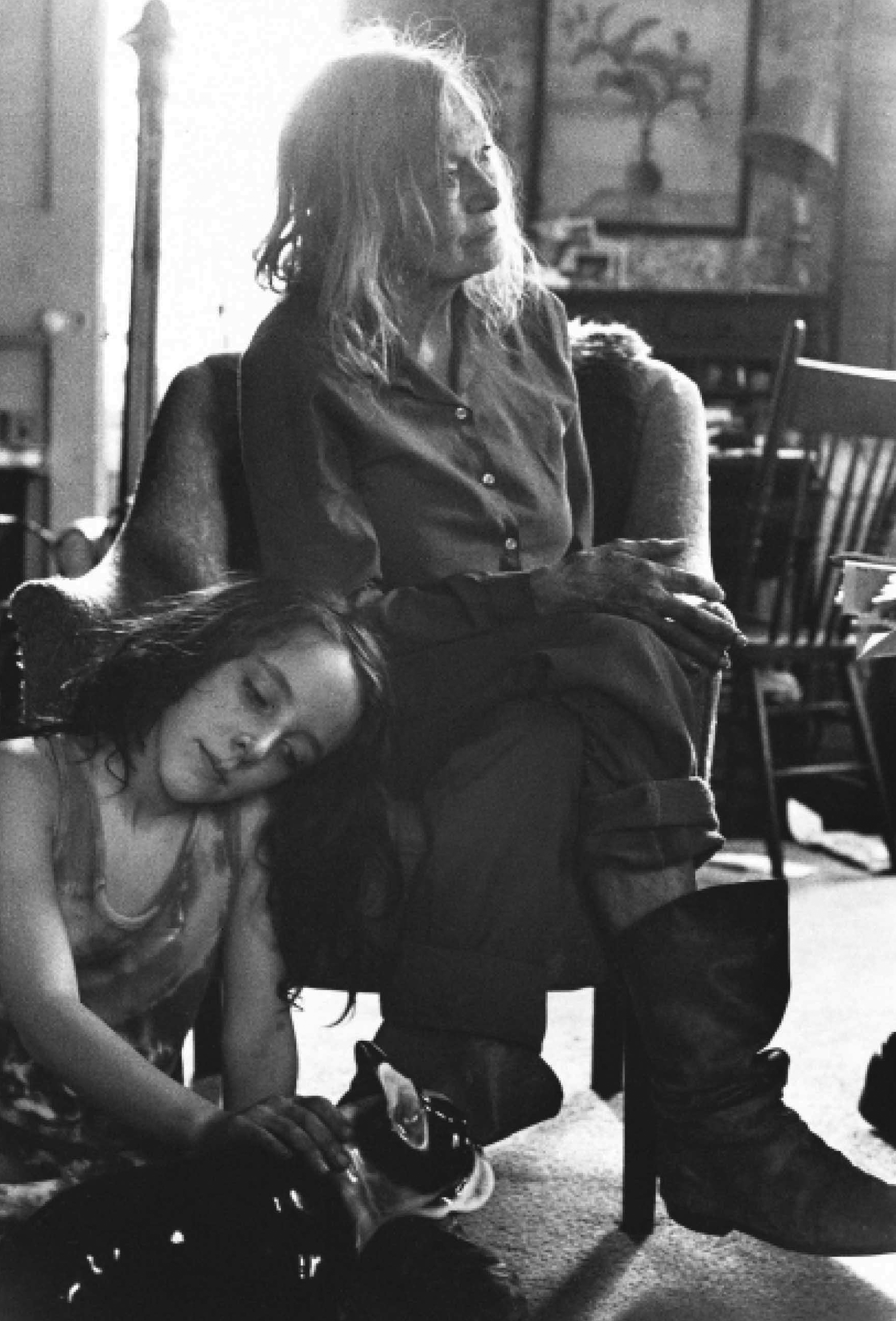

A woman named Evelyn (pronounced EVE-lyn) frequently drove her red Pinto twenty miles up from Pittsboro to try on yoga clothes and thumb through expensive books on bamboo. She would lean against the counter and carry on long, animated conversations with Richard. Even from the other room, she made an impression on me.

Time passed. I moved the yarn shop into its own space, quit teaching, and began taking a photography class. We were learning to photograph people. Although it had been more than ten years since I had seen her, I immediately thought of Evelyn.

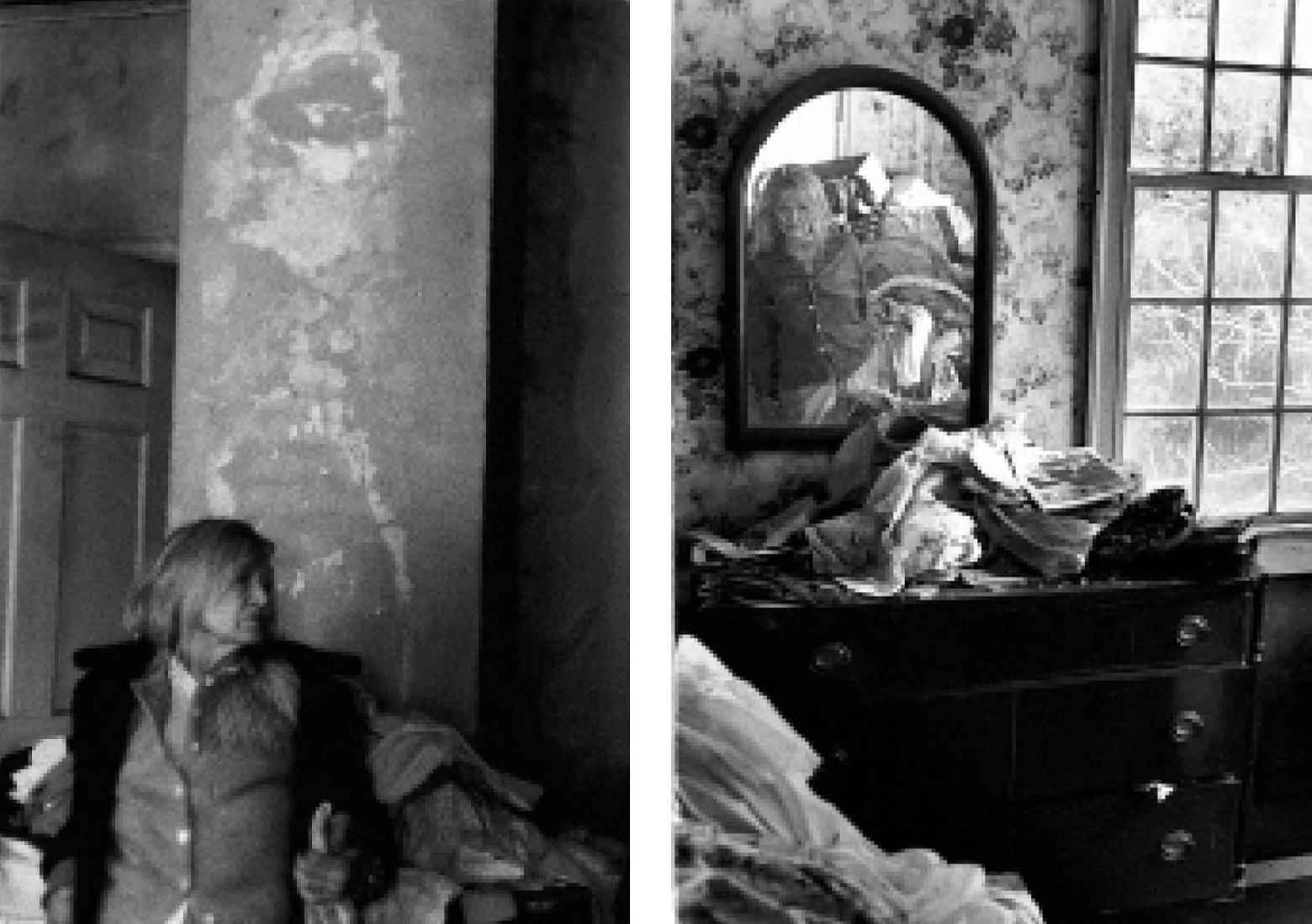

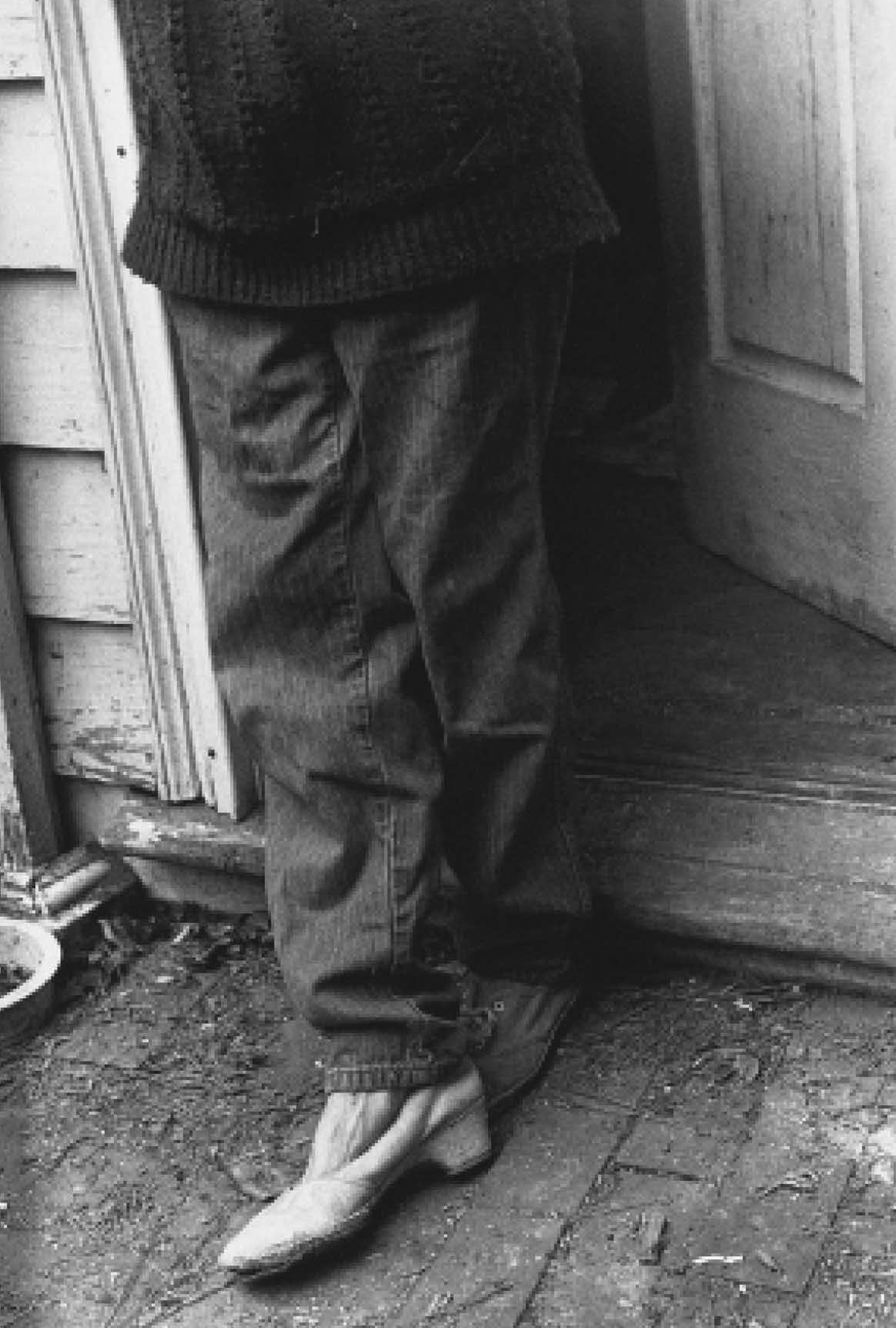

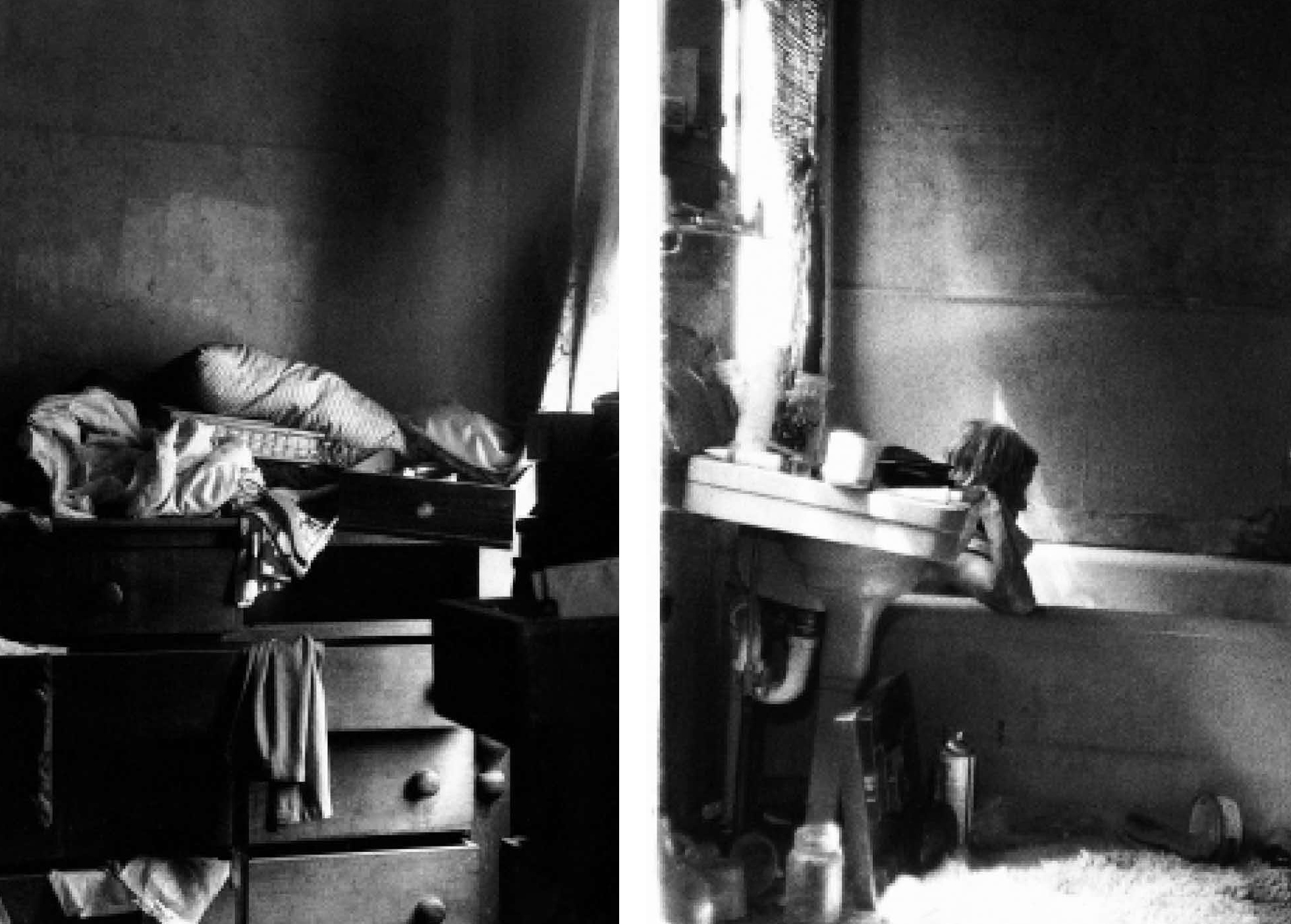

The day I started photographing her, Evelyn was walking with three dogs and two cats through the yard at her family home, a three-story former girls’ academy on the historic register. Although she had once worked in Manhattan, she had long ago come back to North Carolina to care for her parents near the end of their lives. Now she tended the four acres of her mother’s plantings in a loving, hands-off manner and took the same approach to housekeeping, leaving things as they fell. If anyone commented on the way her house looked, she would laugh and say, “You just can’t get good help anymore.”

After the class ended, I continued to visit Evelyn and to photograph her. She took me to Mount Vernon Springs, where two streams emerged from the ground — “one for health and one for wealth.” She pointed out the spot where the old hotel had burned down and where her mother had caught the train to “New Yawk.” I drove her to the grocery store and to pay her bills, and helped check on her perennially failing furnace. She moved to a family-care home outside of town after a chimney fire made her house uninhabitable. Evelyn died in 1995.

— Louanne Watley