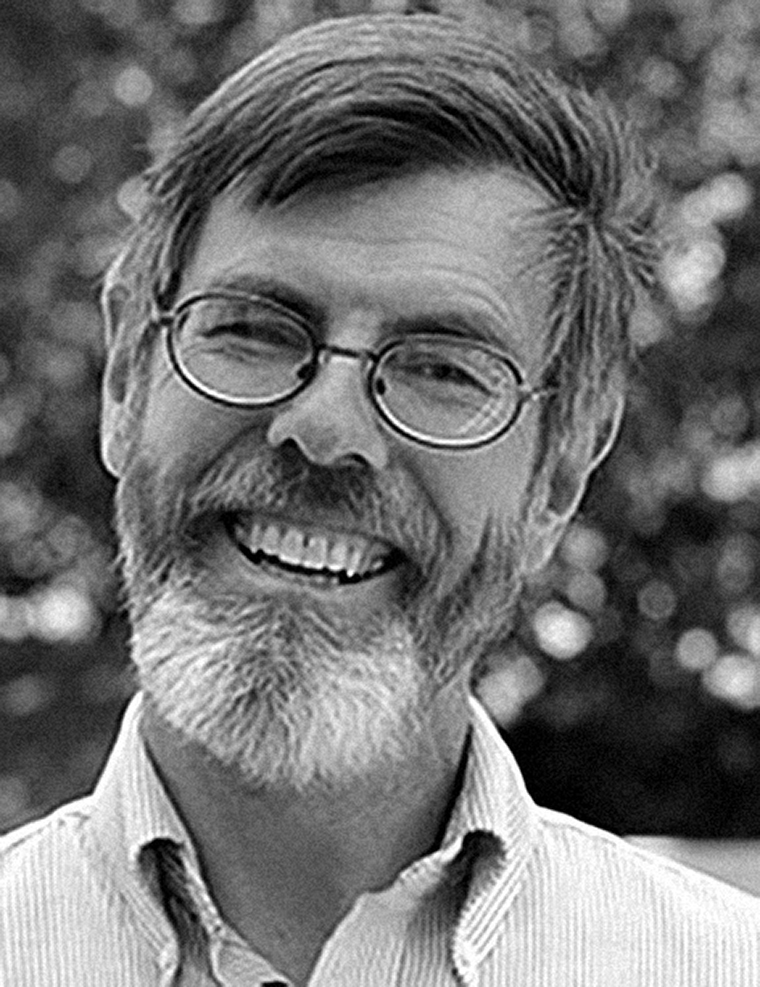

In the early 1980s John Records was practicing law in Oregon, where he and his wife, Glena, were raising two young daughters. Their lives seemed ideal, except for their growing concern about the possibility of a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union. President Ronald Reagan, along with his secretary of state and advisors, had made public statements about the country’s ability to win such a war, and in 1983 Reagan delivered his famous speech calling the Soviet Union the “evil empire.” Born in 1950, Records had grown up the son of an engineer who worked on guided-missile systems, and in elementary school he had read his father’s copy of On Thermonuclear War, by Herman Kahn, which had frightened him with its horrific descriptions of a large-scale nuclear conflict. Reagan’s talk of war revived those old fears.

A few years later Records heard about the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament, an upcoming nine-month cross-country trek planned for 1986. For the sake of their children, Records and his wife decided to participate. Records, who had been inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s strategies of nonviolence and meditation as a solution to even the biggest, most frightening problems, was no stranger to activism. He’d protested the Vietnam War while he was a college student, and his antiwar views had put him at odds with his conservative parents, who’d cut him off financially, forcing Records to put himself through college with scholarships and various jobs.

I, too, took part in the Great Peace March and got to know Records and his family along the way. As we were crossing the Mojave Desert, the group that had coordinated the march fell apart, and the marchers elected Records to chair the organization’s board of directors. He also became the march’s primary media spokesperson and, in his words, “a shock absorber, a lightning rod for people’s discontent and problems.” Before the journey was over, he had lost fifty pounds, and Glena had contracted pneumonia. Physically and emotionally spent, Records was unable to return to being a lawyer. He wanted to learn more about service as a spiritual path, so he and his family moved to Petaluma, California, where he assumed directorship of a program teaching meditation to people with aids and other chronic illnesses.

In the late eighties Mary Isaak and Laure Reichek, two Petaluma residents concerned about the growing number of people sleeping outdoors in unsafe conditions, founded the Committee on the Shelterless, or cots. Records and his family started volunteering on Friday nights at the organization’s small homeless shelter.

In 1992 Records became the executive director of cots. At that time, the organization operated an emergency family shelter with thirty-five beds and a winter shelter, open during cold or wet weather from November until March, where seventy to eighty people could sleep on mats on the floor. Today cots provides nearly three hundred beds each night and serves more than a hundred thousand free meals each year. The organization’s budget in 1992 was roughly $200,000; it is now $2.8 million. COTS employs forty-five staff people, and volunteers donate more than fifty thousand hours annually.

Of the old shelter, Records says, “It saved some lives, but in a way it also enabled and encouraged people to stay homeless.” Under his leadership, cots has taken on a transformational mission, providing its clients with the support they need to make the transition into independent living, including free classes in parenting, job skills, yoga, meditation, and qigong.

I had lost contact with Records over the years, and when I looked him up in 2007, shortly after my wife and I had moved to Sonoma County (where Petaluma is located), I discovered that he had become a local hero. While he has been executive director, cots has won a Jefferson Award for Public Service and multiple awards from the United Way. The Van Löben Sels Foundation of the Bay Area gave the organization a grant to document its program so that it might be replicated in other communities. COTS has a website (cots-homeless.org) and even its own YouTube channel (youtube.com/cotspetaluma).

This year, on the occasion of its twentieth anniversary, cots has published Invitation to Service, a book of stories and testimonials from staff and clients, available from www.lulu.com. I sat down to talk with Records at his home in Petaluma last January, just before the book’s release.

JOHN RECORDS

Polonsky: How did you come to believe that you could help homeless people?

Records: I grew up with mental illness and alcoholism in my family. My mother took her own life when I was eight. My father was an alcoholic and was in and out of mental hospitals. There was a time, I believe, when my father was on the street. I saw the pain my parents suffered and caused, but I also saw their love and kindness and potential. So I’m relatively comfortable with dysfunctional behavior, and part of my own healing has been to realize that these painful experiences can awaken my compassion for people who have similar or worse problems than I had.

Most homeless people have led incredibly painful lives, enduring trauma and neglect that would have killed many of us. With their history, they often feel no hope for a better life. At cots we use something called “explicatory narrative.” We help people tell their stories in a way that honors their struggles, so that they come to appreciate the strength they’ve shown in the face of immense challenges.

We have people on our staff who were once homeless. One staff member was on the street for seven or eight years using methamphetamines and alcohol. Now he manages all our programs and has a family and a great life. He’s living proof that it’s possible to come through homelessness and contribute to a community.

Polonsky: Petaluma is a pretty affluent city, yet even here there are so many homeless. Why is there so much homelessness everywhere in the U.S. today?

Records: We have an economy in which even people who are not damaged are struggling to make it. So suppose you’ve been profoundly wounded as a kid, and those wounds impair your judgment and resilience as an adult, while you’re also grappling with an unforgiving economy. Kaiser Permanente, one of the biggest managed-care organizations in the U.S., took a survey of southern-California patients in their fifties. They found that 25 percent of the women and 16 percent of the men had experienced contact sexual abuse before the age of eighteen. And sexual abuse is just one of eight common traumatic childhood experiences the study identified that profoundly affect emotional and physical health, self-image, and decision-making ability. As a group, homeless people have had a lot of these experiences, not to mention ongoing trauma and neglect as adults.

Polonsky: You’ve been to India. How does homelessness there compare with homelessness in the U.S.?

Records: Many people live on the streets there, but often without the pathology we associate with poverty here. They appear to be members of a functioning community, not mentally ill or addicted or victims of domestic violence. On the streets of Calcutta I saw people in functional relationships, sleeping and eating and cooking together. It was much different from, say, going to a homeless camp in Petaluma and finding people who are disturbed and addicted and often involved in criminal activity. We tend to think of poverty in strictly economic terms, but there’s also impoverishment of community and relationships.

Polonsky: COTS also does a lot of work with homeless families and children. Do they present special challenges?

Records: Well, they have different needs. We offer parenting classes for homeless mothers and fathers, in which they learn about child development and also get emotional support from others in the program. Often parents who come to cots use abusive methods of discipline. They scream and hit, because that’s what was done to them as kids, and it’s all they know. So we say, “We respect your desire to control your children, but you can’t hit them here.” And since we’re telling them they may not hit their kids, we have to show them nonabusive ways to discipline.

Meanwhile we teach the kids how to express their needs, and we encourage them to develop big, healthy dreams for the future. At one point in the course, the kids make collages that represent their dreams, which they present to their parents. This encourages parents to behave in ways that support their children’s dreams. Again and again I’ve seen how people’s love for their kids has prompted them to get their lives together.

COTS serves to remind most of us that our fragile bubble of privilege and comfort can be ruptured at any time; that we, too, can be broken and brought to our knees; and that if we haven’t been brought to our knees yet, it’s only because we haven’t been hit hard enough.

Polonsky: What other healing support does cots provide?

Records: Thanks to volunteers and donations, we offer onsite medical and dental help, as well as an acupuncture clinic and a trauma clinic.

A couple of years ago I approached the Institute of Noetic Sciences, which is based in Petaluma and has an international reputation for consciousness research. I said, “The people who take advantage of your programs are generally people of means who have their lives in order. That’s like fine-tuning a Ferrari. Shouldn’t ancient wisdom teachings be available also for people with no means at all, whose ‘cars’ — to extend the analogy — have been totaled?” So now we have a program, At Home Within, that offers instruction in hatha yoga, creative visualization, meditation, energy work, and more. Preliminary results are very encouraging. Participants have reported relief from anxiety, chronic pain, and insomnia.

Polonsky: As cots has grown, have you come up against resistance from the surrounding community?

Records: Yes, a police officer who worked in another community phoned us and said that homeless people are “garbage.” I imagine his work had brought him in touch with human beings at their worst, homeless people among them.

I sometimes tell that story when I give a public presentation. I’ll tell the audience that there’s some truth to what that caller said: Garbage is something that we have used up and thrown away. That’s what’s happened to people who are homeless. Sometimes they’ve hurt themselves, but more often other people have hurt them. They were damaged and then discarded. We take the trouble to recycle newspapers and tin cans. Shouldn’t we try to salvage human beings?

Another time, after a public hearing in which the city council approved a new facility for us, a woman stormed up to me and shouted, “When the next Richard Allen Davis happens in this community, it’ll be on your head!” Richard Allen Davis was the man who abducted and murdered twelve-year-old Polly Klaas in Petaluma back in 1993. My daughter was a schoolmate of Polly’s. They were in band class together. My entire family participated in the search for her. I would walk around town and see the posters with Polly’s face and just break into tears. Polly’s death cast a pall over our community for years.

So this woman at the hearing was equating homeless people with a murderer and child-rapist. But my wife used to work for the Polly Klaas Foundation, and she can tell you that, in fact, the person who harms a child is far more often someone the child knows and trusts: a family member, a coach, a clergyperson.

So part of my work is to help my neighbors see who homeless people are, to see how they’ve been hurt and why they are homeless — not to excuse their shortcomings, but to understand what’s happened to them and ask, “How do we help them now?”

One way we can help is by raising homeless people’s expectations for themselves. Homeless people often feel unable to face life’s difficulties. So if we can help them to accept the challenge of, say, not using drugs or alcohol, or working for a living, they begin to see that they have the capacity to do these things.

We had one client whose stepdad had regularly beaten him with a two-by-four when he was a kid. The boy would run away from home, and when the police would pick him up, he’d beg them not to take him back to his house. As an adult this man became an addict and lived on the streets for decades. But with a huge amount of support from many people over the years, and after numerous slips and relapses, he’s now a civilian supervisor on a military base. He’s saving up money to buy a house.

So we might say to someone, “OK, it’s really awful that you were beaten as a child, or that your dad gave you vodka when you were eight to keep you quiet, or that you have a learning disability, or that you’re in a violent relationship, or that you had a baby by the time you were sixteen. But what now? You have something worthwhile to give this community. Do you want to work together on discovering what it is?” And some people don’t. Maybe they’re not ready, or their pride gets in the way. But when they say yes, they enter into a powerful current of grace and healing.

Most people in Petaluma support our work. Even some people who had led a neighborhood’s opposition to one of our facilities later became donors and supporters. That’s because they saw that we made reasonable accommodations to their concerns, managed the facility well, enforced the rules, and respected the neighborhood.

In my view, the Polly Klaas tragedy makes it all the more remarkable that Petaluma has embraced our mission. Some residents have even told me that cots is part of how Petaluma defines itself. COTS serves to remind most of us that our fragile bubble of privilege and comfort can be ruptured at any time; that we, too, can be broken and brought to our knees; and that if we haven’t been brought to our knees yet, it’s only because we haven’t been hit hard enough.

Polonsky: How do you handle malcontents? I’m sure not all your clients are cooperative and receptive to your programs.

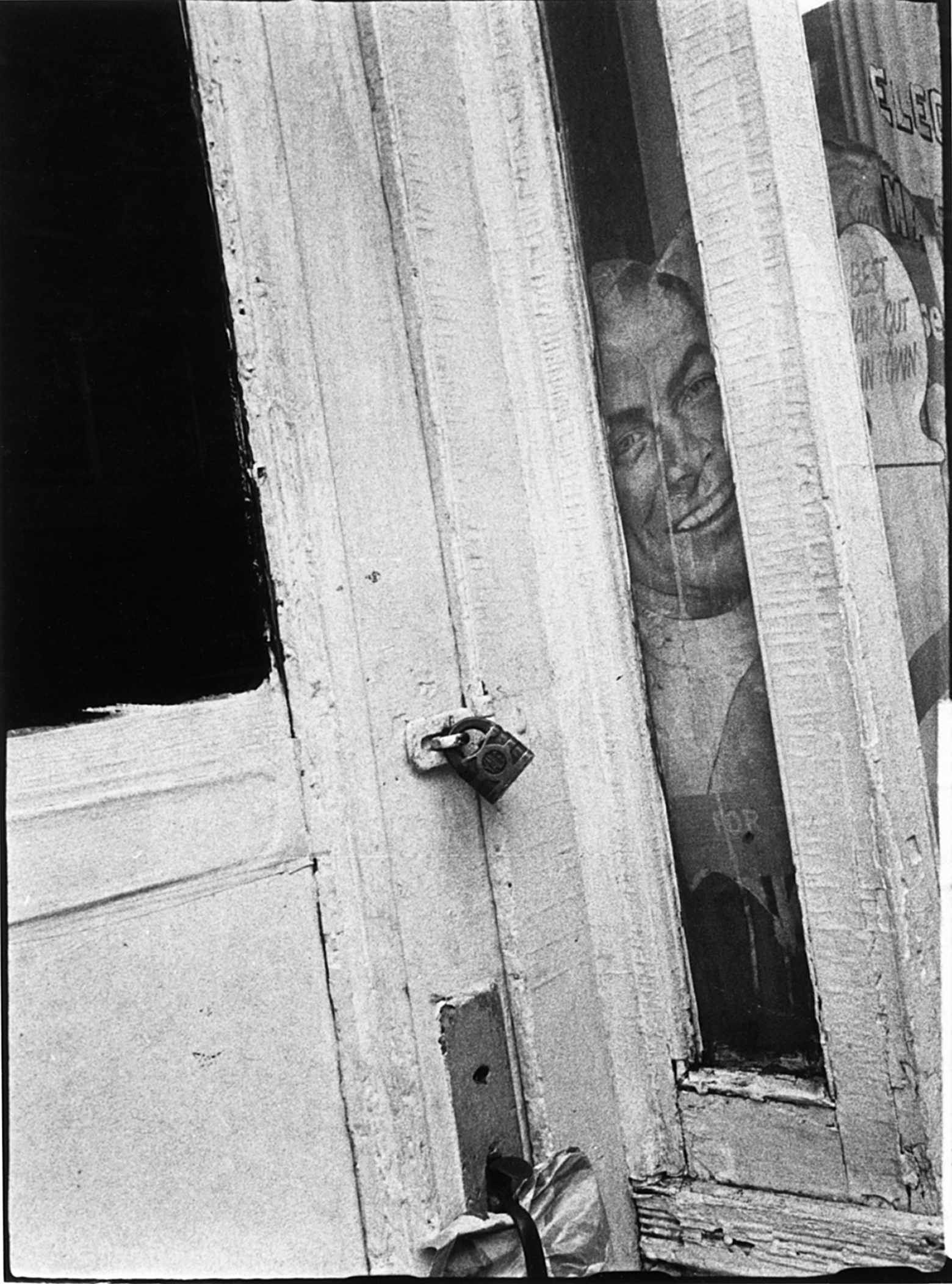

Records: That’s true, and I’ve had my life threatened more than once. But then, I once lived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in a neighborhood we compared to a war zone. Dealing with threats here is not much different from adapting to a city with a high crime rate: when necessary, you watch your back and use caution.

Dealing with homeless people who are upset is similar to dealing with anyone who’s upset. Running clean and sober facilities greatly reduces dangerous behavior. Yes, people get nasty and mean sometimes, but the program participants themselves help settle down those who are making trouble. Our staff members, many of whom were once homeless, are good at defusing tension. If all else fails, sometimes we have to call 911, but as cots has grown, it’s gotten more and more stable. It’s a combination of safe policies and procedures, experienced staff, and self-selecting program participants who want healing and transformation in their lives.

And the transformative aspects of the work apply to everybody. Volunteers thank us for the opportunity to serve. People want to connect; they want meaning in their lives. We’re all finding our way, stumbling and falling and getting up again. In a sense, it’s easier to be homeless, because then it’s clear you need to change your life. Food and shelter are necessities, but I think being loved is just as important. Many people are materially comfortable but feel alone and estranged. I think Mother Teresa alluded to this when she spoke of the “poverty” among the rich in our country. We all need love and support and structure. You can say, “This one’s homeless; this one’s not.” But I think, from a God’s-eye view, there is probably not a lot of difference between the most highly accomplished human being and the most broken.

When Jesus told us to serve the “least among us,” I think he was offering a spiritual path that’s not limited to Christianity. Working with people who are hungry and need to be fed, who are thirsty and need something to drink, who are in prison and need visitors, or who are naked and need to be clothed opens up blessings in our lives.

Polonsky: You make it sound so appealing. Why don’t more people volunteer?

Records: A lot of them feel they don’t have time. But how much time do we spend watching television or surfing the Internet? We may have more time than we think we do. And we might find a greater happiness from giving where we are needed than from being entertained.

Fear is another obstacle. A while back we asked churches to consider taking clients we didn’t have room for in the family shelter, and a member of one congregation did not want homeless people using the church’s bathrooms. There are fears of disease, fears of destructive or violent behavior, fears of being taken advantage of. And those fears are not always unreasonable. You can encounter scary people in this work, and you can get hurt. So you should honor your own needs as much as another person’s and get involved in a way that stretches but doesn’t break you. Part of what cots offers is an opportunity to serve in a safe, structured environment. Then again, even when we are broken in service, we may recover with new strength and wisdom.

I also think people don’t get out there and help because they’re afraid of the world’s pain. There is so much agony just behind the doors of the homes in our neighborhoods, let alone among people sleeping on the street. How do you face all that pain? My own experiences have shattered me several times.

Some activists are driven by a sense of outrage. I’ve felt that myself, and maybe it can be productive in a way. But anger and desperation are also corrosive; they can eat us up. So I encourage people to do what comes naturally for them. Many people connect with animals, for instance, because they are safer to work with and easier to care for than people. You can even start with a plant. Many of the homeless people we work with take care of plants and pets, because it’s rewarding to care for another living thing.

Polonsky: Heartbreak must be an occupational hazard.

Records: It is. I was at our soup kitchen last week, sitting next to a woman who had been in our program a couple of years ago. She’d gotten a job and a place of her own, and had been doing ok — and then she’d learned that she had stage-iv cancer. She had a deer-in-the-headlights look in her eyes. Later that night, I wept as I thought about her, but I was glad she knew she could come to us for help at the hardest, most frightening time in her life. I saw all of humanity in her: our struggles, triumphs, inevitable suffering and death, and also the possibility that people who care won’t let us struggle alone. We can ask for and get help. Somewhere, somehow there should be love and support for all of us.

Polonsky: In your foreword to Invitation to Service you describe a young girl who was once in the cots family shelter and is now being pimped on the street by her drug-addicted mom’s boyfriend. This news sent you into a tailspin, because you’d felt like a surrogate father to her.

Records: Yes, I was devastated. But it also strengthened my resolve to help make cots a haven from all the harshness and villainy in the world, a place where children are protected and cherished, and their parents are taught to be good parents.

Just to think of the way that tens of thousands of children all over the world die of preventable causes every day — and not just homeless children — the horror of it can tear us apart. But I think it can be good for us to be shattered in this way. It’s an opportunity to process some of the big human grief, to receive as much of it as we can take into our being. As much as it hurts, it’s a blessing.

Homeless people are doing their work. COTS staff are doing their work. I’m doing my work. We’re all works in progress, learning the hard way how to be more comfortable and happy, on a planet for slow learners.

Polonsky: How is it a blessing to receive pain?

Records: It’s a blessing because it means engaging with the truth of our lives, which is that this world is full of overwhelming suffering. Many religions suggest that the pain and injustice are acceptable somehow: there is a loving God whose ways we don’t know but must trust; or that it’s all an illusion; or that we’re reaping the karma we’ve sown. Yet religions still encourage us to help those in need.

But suppose you don’t have faith, and for you all of humanity’s suffering is heartbreakingly, horribly real, and there’s absolutely no sense to any of it. Then the blessing is that you still get to choose how you are going to live in the world. You can change the world from one that is senselessly horrible to one in which there is compassion with your choice about how to live. You can choose that, to the extent of your ability, the people whose lives touch yours will be treated with love.

My view is that until our hearts are broken, we’re less-than-complete human beings. Maybe sometimes we have to ignore the pain of others, just to function. But if we’re incapable of recognizing others’ pain, then we’re fragmented and cut off from ourselves. We all have the capacity to love and to care, but it has to develop, and that process usually involves some breaking, some pain. The payoff comes in a sense of connectedness. There is this painful gouging-out of the stone of our hearts, which can then fill with kindness.

Polonsky: But even you must lose sight of that sometimes.

Records: Well, sure, I experience the normal range of human emotions. Some things that happen at work make me angry. Other times I feel an overwhelming sadness, which can open into a tenderness for all life. But we also laugh a lot at cots.

I bring my own shortcomings and challenges to this work, some of which are rooted in my early life and losses. But to the extent that I’ve offered my being, my hands, my body, and my mind in service, that largely displaces fretful feelings. Last week I was working with a guy who’s an abuse survivor and is seriously ill. He was about to undergo another round of medical treatment, and I said to him, “I don’t know how long you’re going to live, but I know you’re going to be ok.” That perspective echoes through all of this: we’re all going to be ok.

In the book How Can I Help? Ram Dass talks about looking at someone who’s dying from aids and thinking, This person is doing interesting work. That’s true for everyone: we’re all doing the work of our lives. Homeless people are doing their work. COTS staff are doing their work. I’m doing my work. We’re all works in progress, learning the hard way how to be more comfortable and happy, on a planet for slow learners.

Polonsky: But your own life is not as difficult as those of the people you serve. How do you reconcile your relative material ease and comfort with the poverty you witness every day?

Records: I don’t feel like I am witnessing poverty every day. What I witness is people who are getting support and putting their lives back together. They often are eager, happy, and proud of what they’re doing.

If I reduced my economic status to be more on a par with that of the people I’m serving, I don’t know that I’d be more useful to them. Part of my work is to act as an intermediary between the population at large and our program participants. I need nonhomeless people to relate to me, too. I was a lawyer; I live in a house; I’ve got a car; and I think it’s a good idea to help homeless people.

Recently a client thanked me for his new teeth. I’d asked my dentist, as a favor, to make him a new set of dentures. That client looks so different now; he’s handsome! When your teeth have crumbled, there’s nothing like a set of new dentures to change the way you see yourself and the way other people see you. I couldn’t have facilitated that process if I didn’t have a dentist myself.

I do a lot, but not all that I could do, to make life better for our clients. People like Mother Teresa and Gandhi apparently gave without ceasing, and I sometimes feel bad for not meeting their standard. I haven’t given my life over fully to this work; I haven’t become the work, as they did. I still have a somewhat normal life, but on balance I’m satisfied with that, because it has permitted me to be a good father and husband and to enjoy my life.

Polonsky: How successful is cots in helping its clients get jobs and find permanent homes?

Records: There are different definitions of success in this work. Sometimes it’s just getting a mentally ill man who’s living in the bushes to come in for a shower. We take people as we find them. More than half of our clients do find employment and permanent housing, but it’s unrealistic to expect that result for all of them. Homelessness is like being down a deep hole. Our programs provide a ladder to use to climb out of the hole. If somebody was born with a learning disability, abused as a child, given drugs and alcohol in elementary school, sexually active at age twelve, and living on the streets at age fourteen, then that person has to climb a long way to get out of the hole. And if they’ve been thrown back down repeatedly by an abuser, then they might not even dare try to climb out again.

A person’s rate of progress can depend on a lot of things, because there are so many causes of homelessness: economic, biological, and psychological. One young woman at the shelter had a learning disability. After having been raped by her father, she’d gotten heavily into drugs and alcohol, which had made her situation even worse. But ultimately she was able to turn it around, and now she has a great life. Another client was a contractor whose life had fallen apart after his wife had died of cancer. For him it was a big deal just to come and eat in our soup kitchen. He’d been eating out of dumpsters for years, yet it was humiliating for him to accept free food from a person across the counter. For him that was a first step out of the hole. This man now has his own home and pulls other chronically homeless people off the streets and into cots. But I would say success is simply moving up the ladder, whether all the way or a single step.

Anytime we see somebody who is pushing a shopping cart and talking to themselves or apparently drunk on the sidewalk, we know they didn’t start out that way. They were once every bit as adorable as any other child; there was every bit as much hope in their eyes.

Polonsky: What kinds of jobs do your clients get?

Records: It’s a very broad spectrum, depending on people’s aptitudes and previous work experience. One man became a truck driver making fifty or sixty thousand dollars a year. One woman went to work for a medical-equipment company in town. At the other end of the spectrum is fast-food employment and Wal-Mart. But being one of the working poor is a step up for our clients.

Polonsky: How do you help people find housing?

Records: We invite landlords and property managers to come in and teach our clients what their rights are and what landlords’ expectations are. We also teach clients to budget, fix their credit rating, and develop a portfolio that includes letters of reference and a cover letter explaining why they would be a good tenant. And the property managers and landlords who volunteer get a whole new picture of homeless people. They see how earnest our clients are. They’re used to having prospective tenants misrepresent themselves, whereas we encourage people to be honest and explain what’s really going on.

Polonsky: Is it frustrating to work with people who don’t seem to make much progress?

Records: It hurts sometimes to see people making what seem like avoidable mistakes. I work with clients who have led terribly hard lives, and a few have a chip on their shoulder, but that attitude might be all that’s left of their dignity and self-respect. I can understand that. The prayer of Saint Francis is essential to my perspective: “Where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where there is sadness, joy.” The amount of despair, darkness, and sadness in the world is just staggering. So regardless of whether you can help someone put his or her life back together, there is darkness you can light, despair to which you can offer hope. It doesn’t really matter whether you think someone can be helped. It’s great when it works out that way, but that’s not necessarily why you do it.

One of our program participants recently died in her sleep. She was in our transitional-housing program. I spent a little time with her body, to help send her on her way. She had an old Pooh Bear and a Piglet doll in her bed with her. I thought of the little girl she once had been, the comfort and love she had needed, and I was glad that she had at least died in a bed in a dorm room rather than on the street.

Anytime we see an adult who is homeless, we can think about the child they once were and what might have happened to them. Anytime we see somebody who is pushing a shopping cart and talking to themselves or apparently drunk on the sidewalk, we know they didn’t start out that way. They were once every bit as adorable as any other child; there was every bit as much hope in their eyes, every bit as much beauty in them as in our own children. Something happened to them, probably something awful, probably more than once, that broke them and brought them to their sorry state. They were once children who didn’t get a fair break. So let’s honor who they were. Let’s at least give them a fair break now.

Polonsky: What are some places in the system where homeless people continue to fall through the cracks?

Records: There’s a big gap in an area we call “permanent supportive housing,” which is long-term shelter for people who cannot reasonably be expected to make it on their own. We feel that people who can work should work, so we try to support them in finding employment. But some are unemployable. We have a client, for example, who has dementia. He’s a nice man with lots of great qualities, but he’s very hard to work with. He would not go along with us to apply for benefits or for a medical evaluation. We lost him for a while, but now he’s back again. There appears to be no good place for him, but he shouldn’t have to live in a shelter all his life.

So we’re working to develop housing that doesn’t expect residents ever to move on. Some people feel strongly that you shouldn’t provide housing unless there’s some incentive to work. But let’s acknowledge that there are people who don’t have the capacity to make it on their own, no matter how hard they may try. We should at least find them a place to live and keep them stable. It’s the compassionate and rational thing to do — and certainly no more expensive than letting them cycle through the emergency medical system and the criminal-justice system over and over.

We really do know how to help people, but as a society we don’t want to spend our money that way. We wind up taking funding away from programs that help people with mental illness or chemical dependencies. If they were to get help, these people could be a benefit to society instead of a burden, yet we deny help to them.

This work requires patience and an ability to persevere when there are so many things wrong with our system and not enough resources for people in dire need. Our work requires us to make the best of what we’ve got, to be creative and find alternative ways of helping people, and sometimes to beat on the door to get more resources. Right now we’re facing a crisis because the economy is in such bad shape. Donors and sponsors are saying, “Sorry, I can’t help out right now.”

Polonsky: It must be hard to keep going. Do your spiritual beliefs help motivate you to do this work?

Records: COTS doesn’t espouse a theology or belief system. It’s a secular organization. But I think we are a vehicle for the expression of grace in the world. If you open yourself to grace working through you, then grace works on you and in you as well. Grace is what has kept me going.

There was a boy named Steven who was in our shelter at age thirteen. We gave him and his family the usual support, and they moved on in due time, but Steven came back a few years later to visit. He was getting good grades in high school and volunteering in a veterinarian’s office. He planned to go to college to learn to be a veterinary technician. And he brought gifts for the children at cots — toys he and his siblings had purchased with their own money.

When I see the miraculous changes that take place in the lives of homeless children and adults, I am humbled and awed to have played a role in that.