Folk singer Pete Seeger died this past January at the age of ninety-four. To commemorate his passing, we’re reprinting this interview that Howard Jay Rubin did with Seeger for The Sun back in 1981, when Seeger was sixty-two.

In a career that spanned more than seven decades, Seeger lent his voice, his banjo, and his songs to many social causes, including the labor, civil-rights, antiwar, and environmental movements. As a young man he traveled and performed with songwriter Woody Guthrie, whose “This Land Is Your Land” became a national folk anthem. As a member of the singing quartet the Weavers, Seeger helped bring folk music to the pop charts. In the 1950s he became a target of the anticommunist House Un-American Activities Committee. (See “I Sang for Everybody” in this issue.) During the civil-rights era he popularized the spiritual “We Shall Overcome,” and his songs became hits for the Kingston Trio, the Byrds, and Peter, Paul and Mary.

Seeger and his wife, Toshi, married in 1943 and lived in the town of Beacon in New York’s Hudson River Valley from 1949 until their deaths. (Toshi died in July 2013, just six months before her husband.) The couple was dedicated to cleaning up the river through their Hudson River Sloop Clearwater organization, which built the sailboat Clearwater in 1969 and sailed it on the Hudson to spread awareness of environmental degradation.

In Rubin’s interview, Seeger makes reference to the Clearwater and also to political figures of that era, including President Ronald Reagan and U.S. Senator Jesse Helms, a Republican from North Carolina, where The Sun is based. Helms was known nationwide as “Senator No” for his efforts to obstruct legislation on progressive issues such as disability rights, affirmative action, and federal funding for the arts.

As Seeger aged, he became a grandfatherly figure in music, and on his ninetieth birthday, in May 2009, he was honored with a concert at New York City’s Madison Square Garden featuring performances by Bruce Springsteen, Ani DiFranco, and John Mellencamp. Seeger made public appearances almost until the end of his life, ever ready to roll up his sleeves, pull out his banjo, and lift people’s spirits with a song.

— Ed.

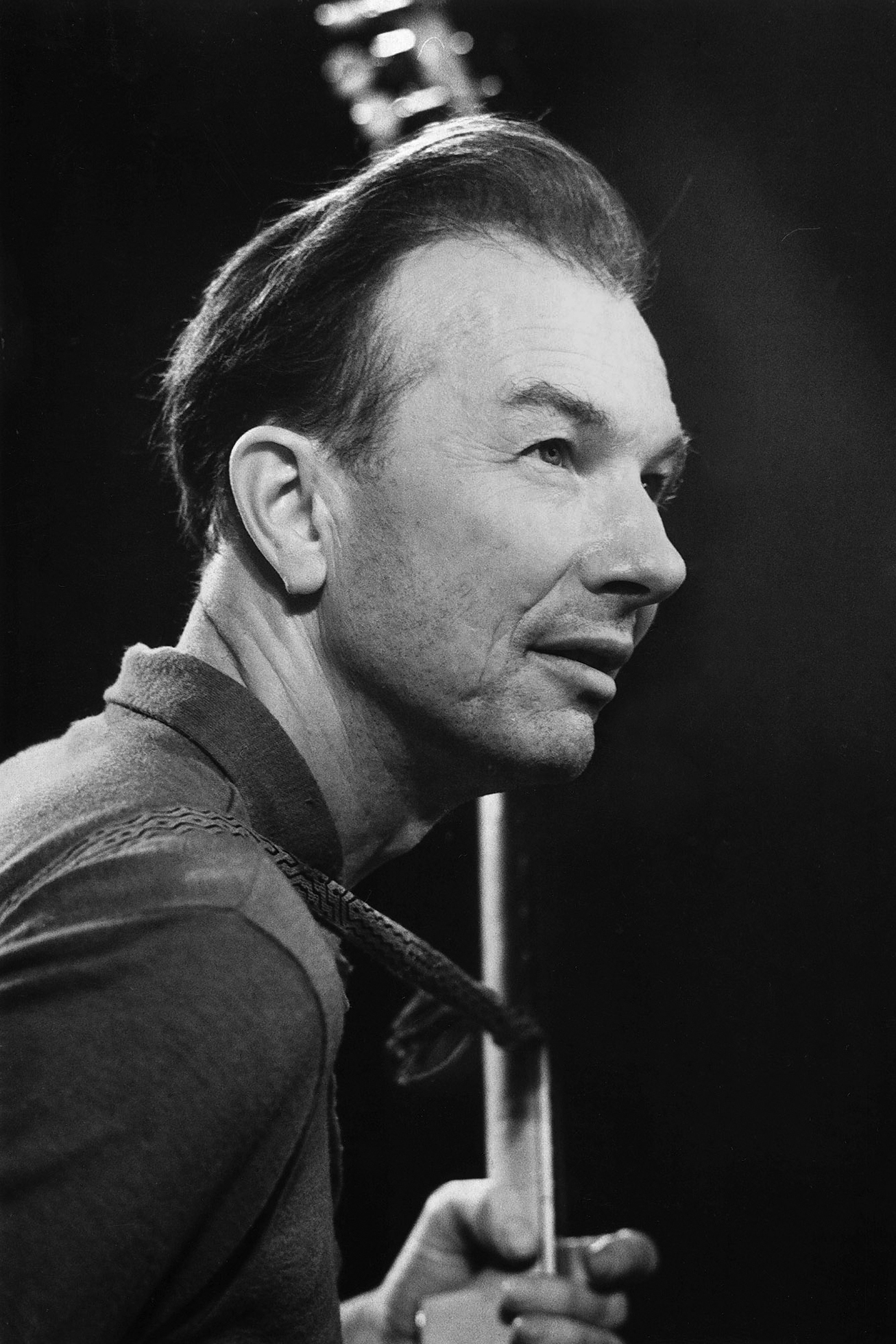

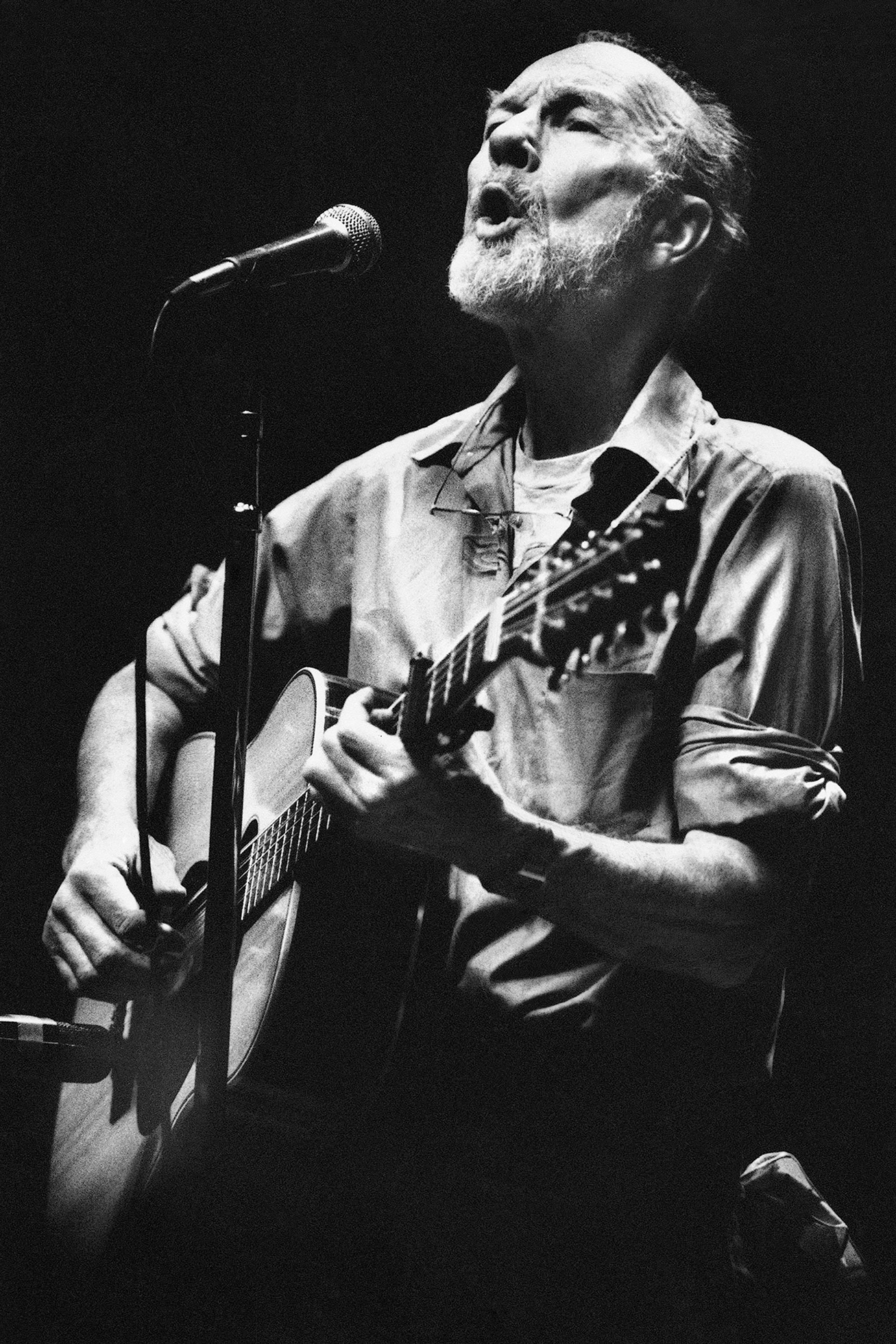

Pete Seeger in 1967 (left), and in 1984 (right)

© AP Photo

Pete Seeger is probably one of the most appreciated folk singers of all time. For me he’s always been like a wise, old friend — the archetypal troubadour, with his graying beard, his raspy, sincere voice, and his old banjo with the words “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender” emblazoned on it. Listening to Seeger showed me that there was much more to music than the rock-and-roll I’d been brought up on.

He sings an amazing variety of songs, borrowing from other writers and cultures, and in a whole spectrum of musical styles. There are hopeful songs (but never naive), wise songs (but never preachy), and songs that are just plain fun. They all get thrown together in the great mixing bowl of his concerts and end up flowing into each other beautifully. It’s easy to believe Seeger when he sings, “Split wood, not atoms,” and to be swept up in his rendition of the great spiritual “We Shall Overcome.” These aren’t idle statements but sincere convictions firmly rooted in his experience.

There is never any of the usual celebrity distance between Seeger and his audience. His concerts become singalongs, a found harmony among the singer, the songs, and the listeners. Says Seeger, “I figure my main function in life is that of a catalyst, bringing some good people together with some good songs.”

Since the days when he and Woody Guthrie traveled together as singers and union organizers, Seeger has consistently worked and sung for what he believes in. Although he denies it whenever possible, he has made immeasurable contributions both to the world of music and to the world that music lives in. It’s been a sharing process — he learns songs from the people he meets in his travels and passes them on. “America,” he writes, “has as many different kinds of music as there are folks.”

In the late forties Seeger teamed up with Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hellerman to form the Weavers. Their enormous popularity and hit songs like Leadbelly’s “Goodnight, Irene” and “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine” helped to bring folk music back into the popular spotlight and to set the stage for the coming folk revival in the sixties. His outspoken defense of humanitarian and social causes earned him the label of “communist” during the McCarthy witch hunts, and he was blacklisted from much of the commercial media. His reply to the charges: “I guess I’m about as communist as the average American Indian.”

In the sixties Seeger was a familiar figure in the civil-rights and peace movements. More recently he has devoted himself to environmental work. He helped to found the Clamshell Alliance in Seabrook, New Hampshire, one of the first antinuclear groups in the country. He is well-known in the New York area as an inspiring force behind the Clearwater, a careful reproduction of an 1850 cargo sloop on which musicians and environmentalists have sailed the Hudson River for twelve years, educating people about the great waterway and the hard task of making it swimmable again. Seeger lives by the river, in a log cabin he built with his wife, Toshi, in Beacon, New York.

When I think of Seeger, I’m always drawn back to his songs, for they embody all that he has worked for.

“Whatever I believe,” he says, “can be easily deduced from my songs. . . . [They] can’t help but reflect my feelings about people, the world, peace, freedom. . . . I’m about as right as my songs are, and as wrong.”

He’s recorded more than fifty studio albums, alone and with friends, and has written or cowritten such memorable songs as “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” “Turn! Turn! Turn!,” and “If I Had a Hammer.”

This interview was conducted after a concert he gave for the benefit of the Flat Rock Brook Nature Center in Englewood, New Jersey.

Rubin: Every time I see you, I’m amazed by how much energy you put out. It’s contagious. Pretty soon everybody’s singing along.

Seeger: The concerts give me energy. It’s a physical fact: the way to get energy is to get your blood circulating. If I’m sitting in the house, on the telephone or trying to write letters, and I start feeling no energy, I go out and chop wood or do something to get my blood running. The modern age may be easy on the muscles, but it’s hard on the nervous system. The happiest people are usually those who use their muscles in some way.

Rubin: Is the Pete Seeger we see on stage different from your private self?

Seeger: On stage I’m relatively well prepared, because I’ve been doing this for forty-five years. In average life I’m stumbling half the time.

Rubin: You never sing gushing love songs, but I feel love coming through your music. Could you talk about love?

Seeger: I use the word as little as possible because it’s so much disagreed upon. This is the problem with a lot of words, and I think anybody who uses words had better heed the advice of Alfred North Whitehead, the old English philosopher, who said to strive for simplicity but learn to mistrust it. He also said that no one should speak more clearly than he thinks. What he is getting at is that a word is an ingenious symbol to stand for all classes of phenomena, and people who use words think that other people understand them. But remember the famous statement — I think Nixon once used it — “I know that you believe you understand what you think I said, but I’m not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.”

Rubin: Do you think the antinuclear movement has been effective?

Seeger: It certainly is effective. The establishment doesn’t want to admit it, but the rallies and marches and songs have had an effect. The country is realizing that nuclear power is not what it was cracked up to be. It’s going to take a while before we really put it out of the way, because nuclear power is closely tied to nuclear weapons, and there’s a large sector of the establishment that doesn’t want to put nuclear weapons away. Curiously enough, it’s an albatross around their neck. People are so scared, and rightly so, of nuclear weapons, they don’t want to see any kind of war get started that could escalate and wipe us all out. So although we live in very dangerous times, I find them fascinating and even hilarious.

It’s hard to say exactly what a song does, or what a word does, until long after. For example, a woman named Rachel Carson wrote a book called Silent Spring in 1962. Two years later you might have said, “Well, it really didn’t make much difference; they’re still using [the cancer-causing pesticide] DDT,” but today DDT is being phased out, and looking back, you could say it was largely her book that started the worldwide realization that we had to stop using it.

Rubin: Do you think we’re really making progress in this fight against pollution?

Seeger: To a certain extent we kid ourselves by thinking we are having successes. Perhaps we are only slowing down inevitable disaster. It’s perfectly possible. T.S. Eliot says, “This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but a whimper.” Maybe we’ll just poison ourselves to death. On the other hand, who knows? We have made progress. The middle Hudson is swimmable now, where it was not swimmable ten years ago. And now the Clearwater is trying to organize a petition campaign in New Jersey and New York State to demand that the cleanup be continued, not slowed down simply because President Reagan wants to balance the budget a little better. There are lots of ways he can balance the budget. It’s going to take about $1 billion more to complete the sewage plants along the Hudson, and that’s a lot of money. It’s five dollars for every man, woman, and child in the U.S.A. But we spend a couple of billion dollars on skiing; we spend a couple of billion dollars on T-bone steaks and fancy foods; we spend more than a couple of billion dollars on vacation homes for our well-to-do people, and several billion dollars on pleasure boating and trips. Don’t let anybody tell you that America cannot afford $1 billion to make the water that flows past the Statue of Liberty swimmable again.

Rubin: Speaking of Reagan, many people are wondering about the next few years. I heard one congressman suggest we may need media censorship if we get more involved in El Salvador. Having gone through such difficult times in the McCarthy era, do you think we might be coming upon a similar period?

Seeger: I’m glad to say that congressman’s not going to get away with it. They’re going to try their best to censor, and to a certain extent the media is always under pressure to censor, but one of the greatest battles that the American people have fought in the last thirty years has been against censorship.

There’s a blacklist all the time as long as you have well-to-do people owning the radio stations and the printing presses. Don’t think that the blacklist existed only in the 1950s. It existed long before then and long after.

Rubin: Hopefully the days of any kind of blacklist have ended, but has it really gotten easier for a so-called controversial singer?

Seeger: Easier, yes, but in a sense there’s a blacklist all the time as long as you have well-to-do people owning the radio stations and the printing presses. Don’t think that the blacklist existed only in the 1950s. It existed long before then and long after.

Rubin: At a civil-rights rally once at Duke University somebody gave you a rock that you put in your banjo case to use if someone ever said they wouldn’t cover a story just because it had no violence. Have you ever had cause to take that rock out?

Seeger: I’ve never thrown it yet. I still carry it in the case.

Rubin: How far do you think we’ve come since those first civil-rights marches?

Seeger: We’ve come a long way. One reason racism seems to be more of a problem today is that at last it’s out in the open. Racism has been there all along. It’s an old, old human problem that’s been with us for thousands of years, and it’s in every country of the world in one form or another. Some have solved it in one way and not solved it in other ways. The French used to insult the Spaniards by saying Africa begins at the Pyrenees. And the English would insult the French by saying Africa begins at the English Channel — as though there were something bad about being African. Language is full of words that are racist in origin. Black is bad. Blackhearted. Blacklist. And these terms are in all European languages. You don’t get rid of these words quickly.

Rubin: Working with words is hard. I write songs, but they often seem naive or coy when I’m just trying to be positive.

Seeger: Learn from the old songs. The best old songs are not just editorials in rhyme. They paint a picture; they tell a story, make a scene, a dialogue. And I am glad to see a lot of people trying to write songs, but they have to realize that writing a good song is extremely difficult. Even well-known songwriters end up having written only two or three songs that outlast them.

Rubin: What would you say is the most important work we have to do right now?

Seeger: It’s working within one’s home community. We know that the big job is to save the world, but where do you start? I’m convinced that if we are unable to work in our home communities, the job is not going to be done. The world is going to be saved by people who fight for their homes, whether they’re fighting for the block where they live in the city or a stretch of mountain or river. But unless they can fight within their own communities, I think they’re kidding themselves. The Bible says, “How can you love God, whom you have not seen, if you don’t love your neighbor, whom you have seen?” Similarly I would ask, “How can you save the world you have not seen if you can’t save the community you have seen?”

Rubin: Are you as hopeful about saving the world as you once were?

Seeger: I’m hopeful in that I think there’s a chance for the human race, but I’m not as hopeful as I used to be. Every year the scientists and technicians invent easier and easier ways by which we can kill ourselves off.

Rubin: You’ve sung about the hard task of separating the false from the true. Do you find yourself needing to revise many of your beliefs in light of new experience?

Seeger: Always. I’m an old revisionist. I think anybody who doesn’t revise his beliefs is kidding himself. We’re always learning new things. Once upon a time they said that whatever goes up comes down. And then they figured out a way to send rockets into space.

Rubin: Are there as many people interested in folk or homemade music today compared with its commercial heyday in the sixties?

Seeger: More than ever. There are millions of Americans making music. Technology has made a few people very well-known — much better known than they should be — and there are a whole lot of other people who once would have been able to make a living performing for their community. Now they’re lucky if they can find an audience. But there are people making music everywhere, even if it’s just three friends who get together with some beer and spend an evening playing songs.

The commercial-music business is a horror; it’s about as bad as the drug scene. People are told they must make it big when they’re young, or they’ll never make it. Terrible.

Rubin: Do you see the drug scene as a problem?

Seeger: My guess is it’s a pretty damn big problem, especially in many cities. Frankly I look on the so-called drug scene as part of a much bigger drug scene. Technology has made it possible for people to take pills or get some quick fix. People think of “drugs” as heroin or marijuana. To a certain extent drugs are also the rich food, the comforts, the petroleum. The U.S.A. is hooked on petroleum. The Bible says, “Lead us not into temptation,” but every year scientists invent new temptations, and they are advertised, advertised, advertised. People go to school to learn how to be good advertisers.

Rubin: How many years have you been playing for people?

Seeger: I’m an incorrigible showoff. I must have been singing ever since I was three years old. And when I was eight, my friend and I gave a concert of sea chanteys. I was in the school jazz band. I never intended to make a living as a musician. I wanted to be a journalist. But I’ve been singing for a living since 1938.

Rubin: What did you do in the years when you were not making enough money to eat?

Seeger: I was making enough money to eat. I just ate very simply. I spent a couple of years hitchhiking around the country. I didn’t have enough money to pay rent. I’ve slept outdoors and slept on other people’s floors, but you can make a dollar go a long way if you’re not trying to eat in restaurants. Over at the shed where we’re building this boat, I usually try to bring some food to feed everybody. Sometimes I’ll bring a sack of potatoes, and two dollars’ worth of potatoes can feed a dozen people. We put them in the fire, and all we need to add to them is a little salt, and we’ve got great baked potatoes flavored by the ashes. My wife can take fifty-nine cents’ worth of beans and feed ten people with bean soup. She knows how to flavor it with onions and garlic and a few other things. Even today my wife feeds our whole family at a fantastically low cost because we hardly ever eat meat. Probably in any one month we don’t get more than a quarter pound of meat, and that’s usually when I stop somewhere for a hamburger.

Rubin: I understand that ninety-five out of a hundred shows you did last year were benefits. Is that right?

Seeger: Arlo Guthrie [son of Woody Guthrie] and I can go out and sing for twenty thousand people, and income from that will keep me going for a couple of months, so the rest of the time I can sing for free. Technology has made it possible for me to make more money than I need. But a lot of other good musicians who once would have been playing for their neighbors and fellow citizens are out of work. It’s one of the bad side effects of technology. Once, every little town had its orchestra. Every community had its square-dance band. Every village had its drummers. And now there’s no way they can make a living at it. They’ve got to do it for the love of it. On the other hand, when you’re doing it for the love of it, you tend to play what you really like, not what they’re paying you to play.

Rubin: At concerts you’re good at getting people to join in. Do you have any techniques that encourage this?

Seeger: Learn from the black preachers. The ancient African technique of oratory, or rhetoric, is full of call and response. The preacher says something, and the audience is supposed to come back. In church they say, “Amen.” In a political meeting they say, “Right on.” In an academic discussion it’s “Hear, hear.” But you don’t just make a series of flat statements. You say something that demands a reaction of some sort. Listen to black preachers; they have the technique down cold. They grew up with it. But you don’t learn it overnight. To get the response takes a good deal of ingenuity. You have to have a rhythm, a ring, a cadence. I bet there are shamans in Africa who do the same thing. You ask a question, maybe a rhetorical question, but you get people to make a response, and their muscles move, their voice moves, their body moves, or their hands move. They take a breath in or let it out, and so what’s going on is not just something in their minds but with their bodies.

People say if you’re going to have a decent house to live in, you’re going to have to start with a good foundation. But I know very well, because I’ve done it, that you can slip a new foundation under an old house. . . . I rather suspect it’s that way with a nation.

Rubin: I think The Sun’s readers would like to hear your recommendation for how they can make the world a better place.

Seeger: I’m flattered that you think I can say anything that hasn’t been said a million times before by other people. I would urge the readers of The Sun, many of whom live in North Carolina, to get better acquainted with a man named Jesse Helms, who is giving North Carolina a bad name. Now, one thing you might do is ask Jesse Helms to write something for The Sun. Give him a chance to be heard. Then when they see how ignorant and foolish a man he is, perhaps they’ll do something about it. It’s really a disgrace to North Carolina, which has a lot of wonderful people in it, that Jesse Helms is up there in Washington, D.C., claiming to represent them. It hurts all America. Undoubtedly there are people like Helms in every country of the world who are outraged by what they see somebody else do, and they figure the way to control it is to start clamping down on freedom of speech. But America has a wonderful tradition of freedom of speech, and one reason that the United States of America is still here is that we have the First Amendment. If we didn’t, we might have gone ahead and used the atom bomb in Vietnam and wiped out the Vietnamese. And, by jingo, the rest of the world would have been so horrified that they would have united to put the U.S. as we know it out of business, the way the world put Hitler out of business. Unfortunately the German people didn’t have any First Amendment.

We have many victories to come. I can’t guarantee them. As I told you, I’m not as optimistic as I used to be. I’ve seen what I thought were very shrewd people do terribly foolish things. Look at Lyndon Johnson. He won the election against Goldwater. He could have stood up on television and said, “My fellow Americans, the election is over. The electorate has spoken. Let’s let the Vietnamese settle their goddamn quarrels by themselves and put American money where it’s needed, giving education and healthcare to every American.” Instead poor Lyndon dug his own grave, and a lot of other people’s graves, too. When someone as shrewd as Lyndon Johnson can be as stupid as that, it makes you pessimistic. Because he’s supposed to know politics. And he knew America, and he just went ahead. The big fools had to push on. I once wrote a song about it [“Waist Deep in the Big Muddy”].

But I’m optimistic, on the other hand, because the American people are full of energy, full of ideas, and although we’re worried, we’ve not given up. Some may be giving up, it’s true. Some are pushing needles in their arms and popping pills, and some give up by saying, “Well, I’m going to get rich myself. I can’t do anything for the world, so I’ll look out for number one.” But in every corner of America I see people who are concerned about the world and about their country, and my only advice is: Work from your home base. You may not decide you are going to live for the rest of your life where you were born, but wherever you decide to settle down, stick it out. Don’t let anybody say, “If you don’t like it here, move somewhere else.” Say, “I’ve got a right to live here. I’m going to stay here. This is my home.” I was born in New York City, but my parents lived upstate. That’s where I spent all my vacations, and after World War II my wife and I moved up there, and we’ve lived there for thirty-two years, and it’s a source of deep pride to me, because I’m accepted now as a member of the community, even though I’m a radical banjo picker.

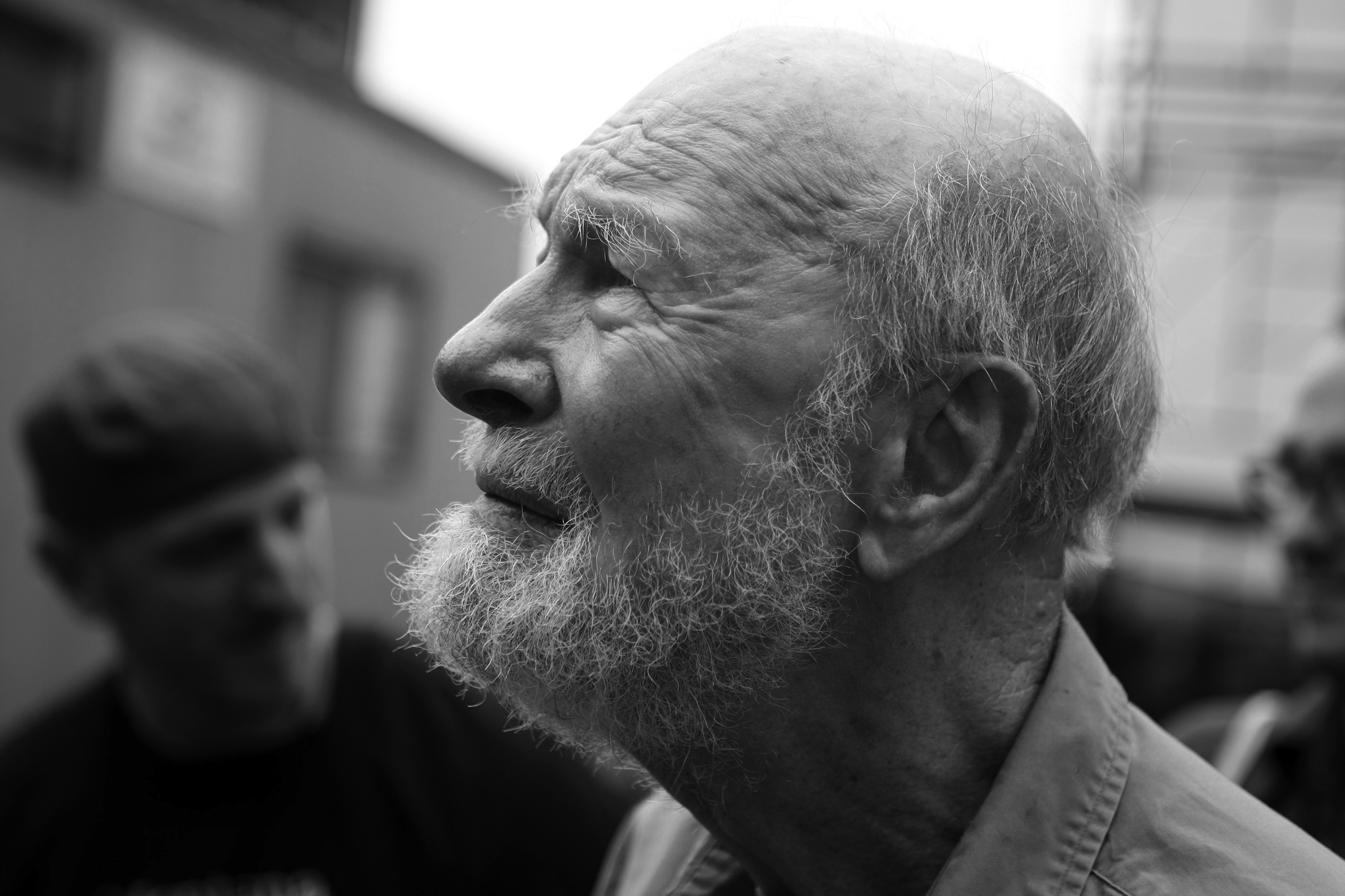

Pete Seeger in 2009

© AP Photo

Rubin: I remember reading that there was a movement against you at one point by some locals.

Seeger: Back in 1967 my wife and I were almost run out of town. Not now. Last year I was handed a beautiful brass plaque on Main Street of Beacon, New York. They had a municipal celebration called Spirit of Beacon Day. I was honored. It was the biggest honor I’ve ever gotten in my life, with my friends and neighbors. And I see it happening all over America. People are getting interested in their own communities and realizing that they’re part of a long chain, and you can’t go out to some idyllic place and form the kind of community you think is ideal. You’ve got to start with where you are. To try and form your ideal community is a cop-out. Somebody’s got to save every little city and big city and small hamlet in the world. And if you’re not going to save them, who is? You’re not going to save them by running away. The most foolish people in the world, I think, are some scientists now who say we’re going off into space to form our ideal communities. The world is lost, so we’re going to build spaceships that will orbit the sun independently of life on Earth. That’s laughable.

Rubin: I get the sense that you don’t expect any kind of sudden change, that it’s a slow process.

Seeger: Sometimes you do make a sudden change. [British prime minister] David Lloyd George once said not to be afraid of taking big steps; you can’t cross a chasm in two small jumps. And all of us, at various times in our lives, take big steps. You leave home, you get married, you have children, you get a job, you quit a job. But nations, too, take big steps, like severing our connection with the king of England and outlawing chattel slavery. But, on the other hand, a lot of things can be done in small steps. People say if you’re going to have a decent house to live in, you’re going to have to start with a good foundation. But I know very well, because I’ve done it, that you can slip a new foundation under an old house. I built my own house out of logs. I’ve added to it and subtracted from it. There’s hardly a house I know that couldn’t be jacked up and improved from the bottom or from the side or from the top, and I rather suspect it’s that way with a nation. You can do a little here, a little there. During the next few years many a house is going to get solar heat. They may open up the south side of the house to more windows; they may put collectors on the roof or add a windmill or a wood stove. But after five or ten years that house is going to be very different. And they didn’t do it all in one fell swoop. So it’s possible that a hundred years from now they’ll look back and say, “Gee, things were sure different way back there in 1981. But we can’t say it all changed in any one year. Some of it changed in 1984, or 1990.”

I’d really like to stick around to see the revolution in energy, because it has tremendous implications for the world. We’re learning that not everything has to be big. Small enterprises can be very, very important. The biggest news story in America in the 1970s was the tens of thousands of local organizations that were started — tens of thousands of local newsletters, local committees.

Rubin: We have the First Amendment, yet we have to shout to be heard above the mass media.

Seeger: Actions speak louder than words. If you’re interested in eating sensible food, rather than putting out a newsletter about it, you’d better go right down to Main Street and sell some good food, right out on the sidewalk. If they arrest you, fight it in court. Say, “I’m selling better food than they are in the restaurant here. I’m giving it away at half the price. How is it you put me in jail? Isn’t that ridiculous?” My wife has done a lot to persuade people toward healthy food not by talking about it but by cooking. She serves a thousand people what we call “stone soup” out of a big cauldron every year at the local food festival. People bring vegetables from their gardens, leftovers from the icebox. At the end of the day we’ve got a wonderful soup.

The printed page can help, and the electronic screen can help, and the still camera can help. But, again, actions speak louder than words, and to a certain extent that’s why the Clearwater is effective. It’s a nonverbal message. People look at that boat; literally millions now have seen it. They may never set foot on it, but they see it from a distance, and they say, “Oh, yeah, those are the people who want to clean up the river. I wonder what luck they’re having.” Little by little the word gets around.