Being sick is like being cast into a barren land, seemingly barren in the sense that it is impossible to go out to mix with the world. It is a purging I go through several times a year, as my body takes control of my life for me, saying slow down, get out of the fast lane.

I can’t sleep. I think about last night, sitting around the kitchen table laughing and talking, and the moment when I drifted away from our cozy warmth, noticed a heaviness in my heart that had become chronic, and had successfully remained unidentified. When I asked silently, who are you, why are you here, a scene from last weekend flashed through my mind, when Marie visited me in Rhinebeck.

We walked beside the river, watching the grey sky for slivers of sunlight that would hit the Hudson in split seconds and disappear. We had our arms around each other as we walked, and I was in a state of appreciation, every guard down, fed by Marie’s droll sense of humor, her velvet presence, open naivete. We talked about sharing a house in France next year, about personal paths, ambitions that would flower slowly with care. We talked about instant incineration, New York City burning in a nuclear attack, and as if I were speaking of a hurricane, a natural disaster, I said, “And how long do you think it would take to reach Rhinebeck, or Tivoli?” And she said, “A few seconds. It’s what, sixty miles?” “Maybe it’s seventy, maybe even a hundred,” I said. Marie answered softly, “Well, there’d still be some pretty serious problems here.”

The heaviness of the heart reached a fulcrum point then, and it occurred to me that I had felt a daily despair for weeks around the growing probability of nuclear war.

Since the weekend in October when 230 Marines were killed in Beirut and the U.S. invaded Grenada, I have jumped at the sound of a siren of any kind. On my evening walks, I see the Catskills softly rising out of the landscape across the river, ancient mountain tops of an ocean floor, and I feel falsely safe, assume the universe will automatically protect this earth, its cycles, the simple splendor of any ordinary day.

I go obligingly to work with witty, intelligent people who have become my family, my friends, and we create “programs” for the public, which aren’t solutions but atmospheres of music, psychology, spiritual practices, dance and all the healing arts that were once obscure but are now seeping out like lush green grass on a seriously ill planet, the body of a mutating mass mind.

It is, hopefully, a political act, to work this way, to offer alternatives, encourage people from diverse backgrounds and viewpoints to meet on common ground, take a risk together. But there is a growing fear in me that this is not enough, that “emergency measures” must be taken, and I don’t know what they are.

Panic seems unwise. So does excessive vocalizing, or silent depression. Within this emotional confusion I have been feeling subconsciously triumphant that I can still buy ice cream, look happy on my lunch hour, enjoy attacks of hilarity in aerobics, where wall mirrors reflect panting Rhinebeck housewives and me leaping like drunken ballerinas, landing like elephants on the floor.

Sometimes I have spells of emotional emptiness, sit quietly and just want to know the facts. Will I hear a siren first? Will I spot a fireball, like a second sun racing toward me? Should I hide in the closest basement?

In a childhood dream, the bomb is dropped. I crouch behind my mother’s clothes dresser. The explosion is so bright I can see through the dresser as if it weren’t there. Density becomes an extinct state of being in a trillionth of a second.

My thinking about it now is confused, sounds like a band of contradictory characters who shout advice at me from a darkened room: IF YOU BELIEVE IN THE HOLOCAUST YOU WILL CREATE THE HOLOCAUST! DON’T STICK YOUR HEAD IN THE SAND! DISCOVER THE DYNAMICS OF THE SET-UP! Or, the worst: THERE IS NOTHING YOU CAN DO TO STOP IT, SO LIVE LIKE THERE’S NO TOMORROW!

Then my anger rises up at the stupidity that ever brought this drama into being, and the only place I’ve found to send it is the sun.

Several years ago while sitting in the sun, I impulsively asked the sun to take from me what weighed me down, depressed me, to burn it up. And then I asked it to magnify my best, to bring it out into the light.

It often works a heavy magic in the moment. But in the Winter, it is harder to find the sun, or feel it once you’ve found it. So what I might have given away to the sun stays with me, demanding to be digested. I digest it through my writing, my art. This form of writing is addictive because, like true sunlight, it gives birth to the best in me, as well. My lifelong circumstance has been that I am richly rewarded in personal satisfaction for this kind of writing and rarely rewarded with reader feedback except through THE SUN.

When I bought my first SUN, I was just out of journalism school, a promising graduate who never had the nerve to tell her teacher she did not believe at all in a separation between the perceiver and the perceived. As an emerging news reporter I was in big trouble. The discovery of THE SUN was enough persuasion for me to drop any plans to be honored in the halls of Howell, at the University of North Carolina — the second-ranked journalism school in the country.

And becoming close friends with Sy Safransky, who had made his graduate school degree (from Columbia, the top-ranked journalism school in the country!) into a cutting board, finalized my prejudices for writing for myself first, and skipping the performance for the parents, the peers. Even more compelling was THE SUN’s urgency and directness, and Sy’s, that matched my own — a drive to write about and publish personal experience as a public statement, not out of narcissism but because this encouraged others to speak from their own experience rather than echo an outer authority.

For all the times I have cursed Sy’s domination of the magazine, I have also often thought that THE SUN’s subconscious master plan required that Sy set a standard of extreme self-confession, so that anyone else with doubt about telling his or her own stories would feel discrete by comparison, and therefore step forward.

And they did. In large numbers. Many long-time contributors, some of whom I never met in person, became Presences in the office, often more real to me than Sy, or myself, as the soul of THE SUN. There was a woman named Peg Staley who was attempting to cure herself of cancer over many months. We published her letters, every detail of hope and despair. When she died, no one notified us right away. The night of her death, I dreamt I was sitting on outdoor bleachers at “Sun-day school’’ and a woman sat down beside me, said she was Peg Staley. “You look well,’’ I said. “I’m dead,’’ she said, “but I’ll stay in your Sun-day school a while longer.’’

This reinforced my sense that I was finally “in the right school’’ at THE SUN, an invisible university of widely scattered and mostly subterranean teachers and students, who regularly interchanged in a game of musical chairs, a creative chaos characterized by wildly inconsistent quality.

Marketable? Barely. Just barely. In a town like Chapel Hill, which is itself a cosmopolitan stew of creative chaos, it could survive. In a country like the United States, with its pockets of Eugene, Oregon and Berkeley, California and Boulder, Colorado and the other predictable homes of SUN subscribers, it could survive.

I used to think about THE SUN’s survival in much the same way I think about the world’s survival now. The odds aren’t good. Many of the same metaphors apply — “What is to give light must endure burning.”

When THE SUN was my whole life, I had great difficulty believing it would survive, but I acted on the assumption that it would. During part of that period, I lived in a back room of THE SUN office. It was one of those pivotal atmospheres where odors, sounds, a sudden thought imprinted like archetypal art on my memory forever.

I rarely slept well there. The late-night beer drinkers on the street ten feet from the front door were noisy, and there were pigeons living in the roof, always scratching and cooing, and a daring rat who would knock over the trash can on the other side of the room. Sometimes I would lie very still and cry, and think of everywhere else in the world I could be, the disparity of THE SUN’s poverty and its goals of illumination dominating my mind. But my heart said no, this is still a house of hope. It is my choice to be here.

And I would make my peace with it, again, for one more night, and then deep sleep would come.

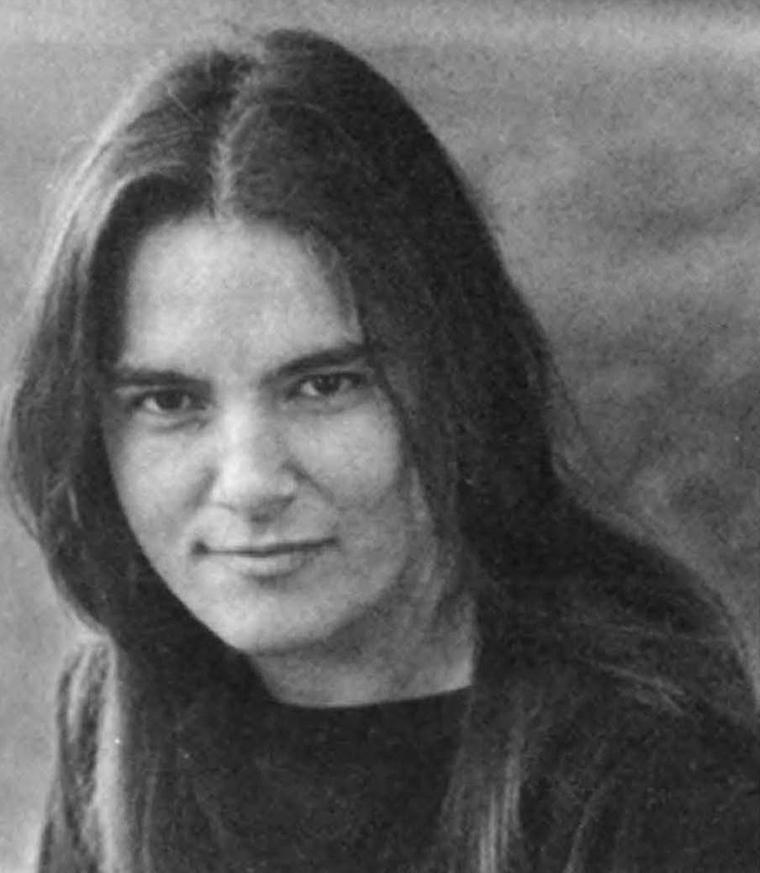

Elizabeth Rose Campbell writes of herself that she was “affiliated with THE SUN from 1976 to 1982 in various and sundry roles: magazine distributor, typesetter, subscriptions clerk, assistant editor, contributing editor, and flower bed manager. She was infamous for being unable to make good office coffee and being chronically 15 minutes late, but was nevertheless, much loved.

“She left the Chapel Hill area in June of 1982 when she began working for Omega Institute for Holistic Studies in Rhinebeck, New York, where she is a member of the program committee that creates more than 100 workshops per summer, which are held on Omega’s campus in Rhinebeck. She is also director of marketing.

“To receive mailings (bi-monthy) of her less saleable but more interesting essays (some of them rediscovered time bombs of the past, others the fireworks of the moment), send $3.00 per month to Elizabeth Rose Campbell, P.O. Box 404, Rhinebeck, N.Y. 12572.”