After our divorce, my ex-wife and I shared custody of our two-year-old daughter, who stayed at my house three nights a week. My daughter would have difficulty falling asleep, so I’d lie in her bed with her, sometimes for hours, until she was out. Then I’d sneak away, only to feel her climbing into bed with me later in the night. Eventually I invited her into my bed, where she’d fall asleep in minutes. I imagined she needed this closeness to make up for our lost time together. I suppose I needed it, too.

My daughter wasn’t a quiet sleeper: she rolled a lot, threw her legs over me, and once kicked me in the throat so hard I couldn’t breathe. Sharing a bed, however, brought us both comfort. As a man, I was aware that some people might see this arrangement as inappropriate, so we pretended she had her own bed. I figured she’d outgrow her need for the odd sleeping arrangement eventually.

Eight years later, after I remarried, she started to sleep in her own room. My daughter is fifteen now and would be mortified if she knew I was telling this story. I’ve loved many women, but I’ve never felt closer to anyone.

Name Withheld

When I was twenty, I married Oscar, a Bolivian I’d met while working on a vegetable farm in Virginia. I was one of the few nonnative Spanish speakers on the farm and could hold my own in conversations over pepper plants and raspberry canes.

When I first saw Oscar, he was on his haunches picking beans. He had a kind face and glossy black hair that fell sexily across his eyes. He smiled at me, and I later learned that his friend, at that moment, had leaned over and said, “I predict you will marry that girl.”

For nearly a year, Oscar and I rented a drafty room in the boss’s modern brick farmhouse. Our full-size bed took up half the space, but we were content to spend most of our time in it. The bed, a hot plate, and a space heater were enough to get us through the four Virginia seasons. Once, when Oscar and I hadn’t left the room all day, his sister Maria left sandwiches for us on the doorstep.

In that bedroom we spoke only Spanish; I was more eager to refine my skills than Oscar was to work on his English. We cooked eggs and greens foraged from the farm. Oscar taught me the folk dances of Bolivia, drilled into me the importance of saving money, and urged me to go back to college.

The bedroom was also where, several months after we’d married, Oscar cried and told me he’d made a terrible mistake. He said he loved me, but he was still married to a woman in Bolivia. I was devastated, and Oscar was genuinely contrite.

We got an annulment and somehow managed to remain friends. Even now, he sends me the occasional e-mail, telling me how his daughters are prospering and how his wife beat breast cancer. He and his family live in the States, and I’ve met them. My friends find this outrageous, but I have no regrets. For a short time we loved each other well.

M.B.

Rochester, New York

I used to wish for the day when I’d want to do something creative, like build furniture or write short stories, as much as I wanted to obey the animal call to the bedroom, where fleeting moments of sexual gratification often ended in confused emotions and broken relationships.

Now that wish has been granted — by age and a pinched sciatic nerve that makes it impossible even to lie down in my own damned bed. Gone are the wasted days of sexual passion. My life is full of cerebral and artistic interests. But I yearn for a night of painless sleep, for a drug powerful enough to dull the pain in my back. The bedroom has become a place to store clothing and confirm that the aging man in the mirror still exists: nothing more. It may as well be roped off with red velvet, like the chambers of a dead president.

Jamie Huling

Nashville, Tennessee

My married bedroom was famous for its swan-shaped bed, crafted by my ex-husband, a woodworker and furniture maker. The foot of the cherry-wood bed was carved into a swan’s neck and head, six and a half feet tall. On the headboard was a painted swamp scene with a built-in reading light, and the sides looked like the sides of a small boat.

My ex still drapes his arm over the swan’s neck and tells the story of Leda and the Swan to impress visitors, especially the women. He was often mistaken for Mick Jagger when we were together, and though his rock-star quality has been dimmed by years, pounds, and smoke, the bed remains fantastic enough to captivate an audience.

As romantic as the bed was, our marriage was troubled. We were both too young when it began. At first I relished my role as supporter of and inspiration to the great artist, but then I learned that his creativity took precedence over my own — unless mine was domestically expressed. There were many problems with our house as well. Though it was a wonder of curved walls, turrets, and fantasy details, few projects were ever completed. There were leaks in the roof and gaps where the walls and ceilings met, and it was heated by wood that he chopped or I dragged in from the forest.

During the last winter we lived together, he left to spend a weekend with his new girlfriend. I was not innocent in that department, but he chose to leave me in that falling-apart house during a winter storm. A cold rain fell and coated everything in an inch of brittle and twinkling ice, beautiful and dangerous.

There had been a persistent leak over the swan bed, and before my husband ran off, he’d suspended a black plastic tarp over it, just in case. The next morning the temperatures reached the mid-forties, and the ice began to melt. When I awoke, the tarp above me was tight as a tick. In the few seconds it took me to comprehend what was happening, the tarp gave way, dumping a load of freezing water all over me and our bed. As I struggled free of the soaking blankets, I said out loud, “This is my last winter in this house.” It was.

Stephanie U.

New York, New York

At twenty-five my son Azja (pronounced “Asia”) moved out of our house and into an apartment with his friend Eric. He and Eric reveled in their new bachelorhood, partying and playing video games till dawn. Although I was happy for Azja, I hated seeing his empty bedroom. So I invited my ailing mother to move in with me, and I transformed Azja’s masculine, African-themed bedroom into a feminine boudoir for Mom.

A few months later Eric called, crying, barely able to talk. He’d gotten back from work that day and discovered Azja on the kitchen floor, dead from an asthma attack.

I hated every moment of the weeks that followed. The worst part was dealing with my suddenly healthy, attention-seeking mother. I needed to be alone. I wanted Azja’s room back.

I took a second job, bought my mother a condo, and reclaimed Azja’s bedroom, re-creating the African décor. Three months after his death, I lay on Azja’s bed, played his drums, and sobbed.

Madonna O.

San Diego, California

I had hip-replacement surgery in December, then an aneurysm in January, which put me in the hospital for a month. When I came home, I moved into the bedroom down the hall while my husband of fifty years continued to sleep in our king-size bed. I would rest better knowing that my recovering body could keep its own hours.

But when I was ready to move back into our bedroom, my husband didn’t want me there. He’d found that he slept better alone; my late-night reading disturbed him, and my snoring kept him awake.

I told myself this arrangement was sensible, but I missed touching, cuddling, knowing he was near. We sacrificed closeness so my husband could have his precious sleep.

Eight years later I think of the fifteen yards from one bedroom to the other as a symbol of the gulf between us.

Name Withheld

In May 1989 I visited a commune and fell in love with the place. I told the residents I planned to return in the fall to live there permanently, and they seemed happy with the arrangement. When I came back, however, there was no room saved for me. The residents explained that people often said they would return, but didn’t.

It was not the homecoming I’d anticipated, but I still wanted to live there, so I moved into the old tobacco barn near the main cabin. The floor was made of uneven planks. The tin roof leaked. Gaps between the clapboards let in rain and mosquitoes. Snakeskins hung from the rafters. In the daytime it was hot as an oven; at night it was cold and drafty. Every morning the roosters woke me up at dawn.

Once I’d convinced the residents I wasn’t going to leave, they found me a room in the main cabin. Looking back, though, I think fondly of the sun pouring in through the clapboards in the morning, the rain hitting the tin roof high above at night, the way I’d fall asleep and wake to the smell of hay. I believe that barn was the best bedroom I’ve ever had.

Nathan Long

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

When our mom, who’d always been a devout and faithful wife, left our dad for another man, it was traumatic for the entire family. My younger brother was especially distraught and did not speak to Mom for two years, until after her second husband had died of cancer. Even then, there was tension between them.

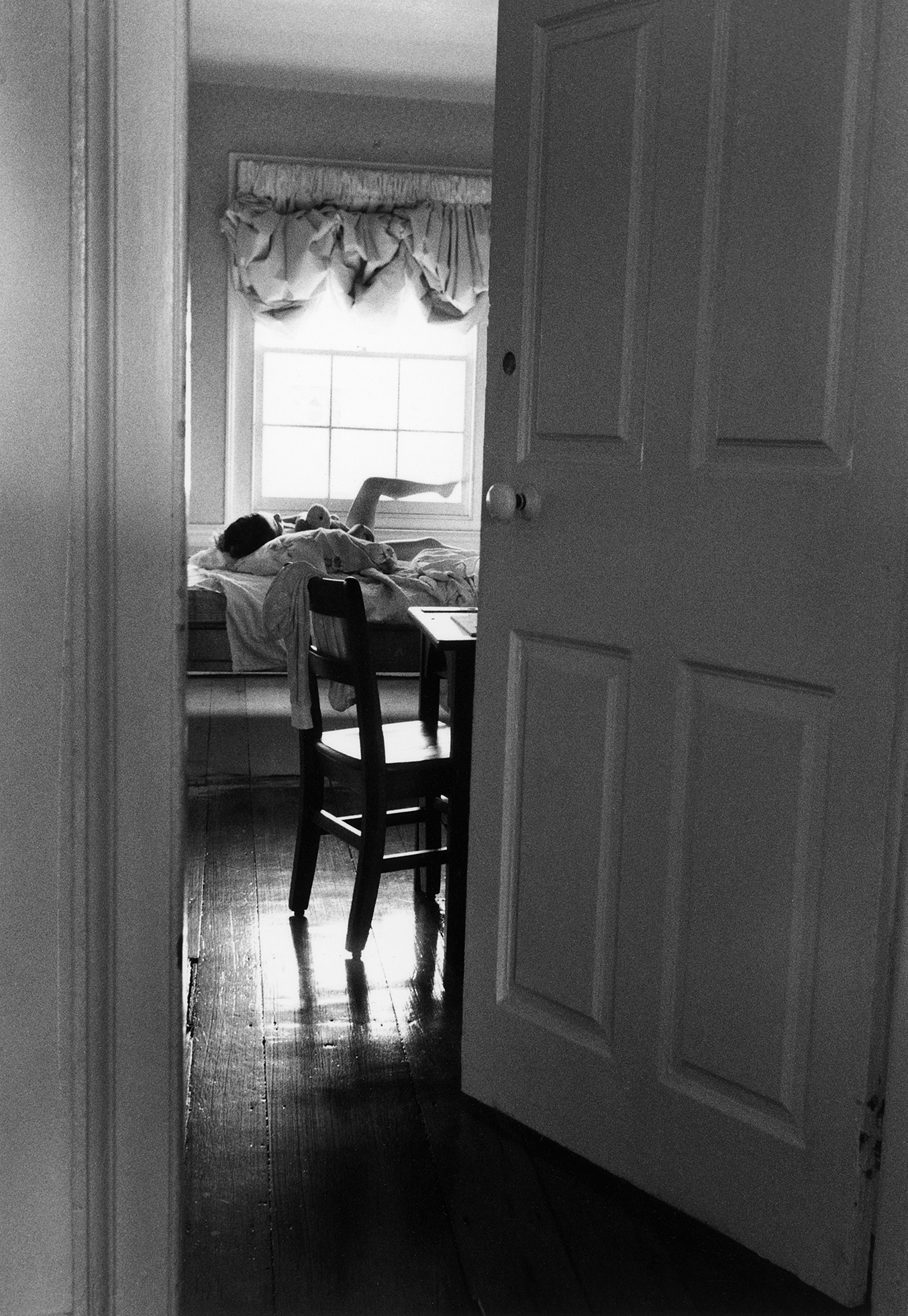

Years later, when Mom was admitted to the hospital for a serious illness and fighting for every breath, I stayed with her day and night. When she showed signs of improvement, I went home to her house, exhausted. Instead of sleeping in the guest room, I decided to take a nap in Mom’s bed. I went to sleep surrounded by her sweet scent, feeling that the sheets were her arms hugging me close, the way they did in my childhood.

When I told my brother about this the next morning over coffee, he said nothing, just continued reading the newspaper. Later I noticed that the covers on her bed were askew, and it was apparent that he had slept there too, though he’d never mentioned it. Our mother died the following week.

Name Withheld

In my late teens I went to visit my grandmother in Denmark and met a young man from the nearby village. He and I spent an evening out dancing, and when we came back to my grandmother’s cozy home by the sea, a single orange lamp was glowing in the guest bedroom where I slept. After the loud discotheque, we were looking forward to a place where we could stop and really look at one another and hear our hearts beating.

When we got inside, we found my grandmother had placed the room’s twin beds so that the feet were together, and between the two beds was a little round table with a candle waiting to be lit (matches provided). Next to the candle was a tray with a thermos of coffee (still warm), two pottery mugs, and a few pieces of homemade spice bread wrapped in soft linen.

The boy and I softly chuckled at this little tableau of my grandmother’s, inviting us to share coffee and cake and perhaps a good-night kiss, and then climb into our separate beds, blow out the single candle, and dream our gentle dreams by the sea.

Name Withheld

I wet the bed regularly until adolescence. Every night I’d pray to God that I’d wake up dry, and nearly every morning I woke up wet. The occasional dry mornings only made the wet ones more devastating.

My poor mom had to contend with washing my sheets and pajamas every day. More than once she lost her temper and said things I know she regrets. Her words shredded my self-esteem. I began so many days filled with guilt, shame, and self-loathing.

Once, my parents had a salesman over who pitched to them a contraption that supposedly helped bed-wetters. The device was placed under the sheets and would sound an alarm if it detected wetness, thereby waking the sleeper. As the salesman explained how it worked, I sat there with my mom and dad, feeling so happy that there was something that could help me. Unfortunately, my parents couldn’t afford it. Tears of disappointment rolled down my cheeks, but they told me they would get an alarm clock and set it for every couple of hours during the night. The big, brass alarm clock’s loud, clattering alarm woke me, but we could never get the timing right, so I still woke up wet.

I finally outgrew the bed-wetting, but not without occasional embarrassing setbacks during my teen years. Slumber parties were excruciating.

Many years later, as I changed my eight-year-old son’s frequently wet sheets and heard my husband start to complain about it, I shut him up in no uncertain terms. Maybe I had to grow up ashamed and embarrassed over something I couldn’t control, but there was no way my little boy would.

Carrie T.

Kalispell, Montana

On Thanksgiving my family is heading out the door when the phone rings. It’s Mary, my sister-in-law, and she’s crying. She has taken their three children and left my brother, she says. They are getting a divorce. When I ask why, all she’ll say is that Jim is involved in some kind of “sex thing.” She asks me to go to their home to check on him: she’s worried he might “do something” to himself now that she is gone.

The “sex thing” is not that surprising to me. I know my brother has hired prostitutes before.

When I get to their house, Jim’s car is parked in the driveway. I knock: no answer. The door is unlocked, so I go in and call for him. Again, no answer. Worried, I search the house and find him asleep in bed. I forgot that he works the night shift.

Jim wakes up, and I tell him about Mary’s call. I ask what sort of trouble he is involved in. It’s not what I thought: Jim is sexually attracted to children. He confessed to Mary that he had touched their children while they slept, and had done the same to her nieces and nephews when they’d spent the night. (I breathe a sigh of relief that my own sons have never slept over at their house.) He admitted this to Mary because he wants to stop and seek professional help. He’d thought she’d be sympathetic, but she left in a rage, promising he would hear from the police and her attorney.

Then Jim tells me he was repeatedly molested and raped when he was nine by a man who was staying with our family. He protested several times to our parents, but they ignored him. Later our mother told him she’d been molested as a child and assured him that he’d get over it, as she had.

Jim and I hold each other, and I cry for the little brother I remember, and for the man I thought I knew.

Patrick

Issaquah, Washington

When I was growing up, my bedroom had an upright piano in it. The instrument towered over me as I lay in bed at night and thought about how much I hated piano lessons and having to practice while other children laughed and played outside my window.

My parents were doctors and had offices in the basement of our house. They didn’t want my practicing to disturb their patients, so the logical place for the piano was in my room, on the second floor. It was too wide for the staircase, however, so my father had hired a crane to hoist the piano onto the upstairs balcony. I remember looking out my window at the piano, bound in chains, dangling in midair, monstrous and alien.

I’ve never understood why my father insisted that I learn to play the piano. He didn’t listen to music or go to concerts. He’d studied violin as a boy but had given it up. Maybe he regretted that he hadn’t stuck with it, and now he was trying again, through his daughter.

When I told my father that I didn’t want to take piano lessons, just tennis lessons, he took immediate action: he stopped the tennis lessons. After all the trouble he’d gone to getting the piano into my bedroom, he was determined I would learn to play.

Years later, when we got rid of the piano, we hacked it to pieces with an axe to get it down the stairs.

My father often said, “As long as you live under my roof, you’ll do as I tell you.” The entire house was his domain. Claiming a space of one’s own was out of the question. Bedroom doors could not be locked, and he and my mother came and went as they pleased. If my father opened my bedroom door after my bedtime and found that I was still awake, he’d be angry.

The last time I slept in that room, as an adult, my parents were away. I’d been to a bar nearby and was high on drugs and alcohol. I picked up a man and brought him home and had sex with him on my childhood bed. I never slept there again.

June G.

Brooklyn, New York

My boyfriend’s parents did not believe in premarital sex and expected him and me to wait until marriage. At his house we weren’t allowed to close the bedroom door, but this did nothing to stop us. We had sex on the dock, in the field, even in a church library behind an unlocked door. I have no idea why we weren’t caught.

Now he and I have been together longer than we haven’t, and our once-firm bodies have softened with age, but we still sneak around — so our three children won’t catch us. Behind our locked bedroom door, on a squeaky bed a few feet from our daughter’s nursery, we have muffled sex — the best of our lives. We’ve recaptured the feeling that we are getting away with something.

Heather Cori

Olympia, Washington

My dad worked out of town during the week. While he was gone, I slept with Mom. I dreaded Fridays, when Dad would inevitably come home drunk and looking for a fight. Wanting to stay close to Mom, I slept on the sofa outside their room. I’d put a pillow over my head to muffle the sounds of Mom saying, “No, get off,” and the bed banging against the wall.

One night Mom escaped. I pretended to be asleep and watched her crawl under the piano bench to hide. She remained perfectly still while my dad searched for her, panting and swaying back and forth until he finally passed out.

Years later, after Dad had open-heart surgery, I secretly celebrated; his sexually active days were over.

With time I saw the better side of the proud, hardworking man Mom had fallen in love with — and continued to love until the day he died. But one burning question still lingered. I asked Mom, “In fifty-five years of marriage, did you ever have an orgasm?”

A long silence followed, and I thought perhaps I’d overstepped my bounds. “No,” my eighty-year-old mother finally said, without anger or sadness. “And it’s too late to do anything about it now.”

Lori S.

Elysburg, Pennsylvania

My cousin was four years older than I was. When our mothers wanted to talk, they’d send us to his bedroom, where he and I played cards. His room smelled of dirty laundry, model-airplane glue, and another, unfamiliar scent. I felt honored to be allowed in there, a girl in an older boy’s private sanctum.

One day, while my cousin dealt the cards on the carpet, he leaned over and kissed me on the mouth. Then he suggested we lie on the bed and play a new game. Being brought up in proper English fashion, I did as I was told. Once we were on the bed, he climbed on top of me and said we had to be quiet. Both of us remained dressed while he rocked back and forth. Then he abruptly got off and stood up. The strange smell that permeated the room grew stronger.

That day I learned that older males liked females to lie still and say nothing. It took me years to figure out what my own desires were.

Jill E.

Portland, Oregon

After my father died, I waited a week before going into his room. (He and my mother had separate bedrooms.) Everything looked the same, but it felt different, as though it were a place I’d seen only in pictures.

It still had a stale, stuffy cigarette smell, the fabrics dulled by smoke and faded by sunlight. His eight belts hung from their hooks by the door. His old patchwork comforter lay on the bed. Flannel shirts with holes hung in his closet. On the wall was a portrait of his side of the family: serious-looking people, all now either dead or pushed away by a grudge. I was never told much about them.

Lying on his bed, I inhaled his scent and remembered him on oxygen, a lit cigarette waggling in his pursed lips. I half expected him to walk in and tell me to get the hell out. Staring at his fake-wood-grain alarm clock, I realized he would not be coming back.

“What are you doing in this room?” my mother said when she found me. “You know you shouldn’t be in here. Why don’t you come in my bedroom. We’ll just shut this door behind us.”

Jennifer Harmer

Fairborn, Ohio

When I was twenty-nine, my husband was killed by a drunk driver, leaving me with a one-year-old and a three-year-old to raise by myself. Seeing how devastated and overworked I was, my sister suggested I overhaul my bedroom and turn it into a refuge. We bought fine sheets, down pillows, and drapes that matched. I retreated to that room often.

Twelve years later I am remarried, with two healthy teenage boys and an adorable daughter. I don’t spend much time in the bedroom anymore. I sleep, make love, and get dressed there. That’s all.

Shelley Murray

Burlington, Ontario

Canada

My mother implored me to tell her what was wrong. I insisted there was nothing.

“You haven’t left your bedroom in three months!” she cried.

I laughed defensively, but she was right. Other than when I went to school or to my part-time job at the pharmacy, I was alone in my narrow bedroom, with its dusty Venetian blinds, small student’s desk, scratched-up dresser, and wobbly table that held my stereo. I wrote stream-of-consciousness prose in my notebooks, listened religiously to Sonic Youth and Pink Floyd, and gazed out my window like a ghost.

That fall my bedroom was a haven from the confusing world outside. I was a scared, depressed kid who smoked pot, took acid, and cried a lot. I contemplated suicide but didn’t have the energy to go through with it. The closest I came was gulping a handful of aspirin after a girl broke up with me over the phone. We were both sixteen.

One way I passed the time was to make strange tape recordings, mixing random bits of television shows, radio programs, and music. One tape I titled Ars Moriendi (The Art of Dying). I’d read that the ancient Greeks considered death a rite of passage to be celebrated, not mourned. I listen to that tape now and hear a record of someone who’s losing his mind and preoccupied with death.

Sometimes I was unable to do anything but stare at the ceiling, daydreaming and hallucinating. The creek across the road would become a thundering torrent after a storm, and the noise sometimes frightened me. I would distract myself with more weed and beer, scribbling madly in my notebook, laughing or crying over nothing, living through another day in my bedroom.

Shawn Montgomery

Portland, Oregon

As the only girl in a family with three boys, I spent a lot of time in my bedroom. Alone there with my books, my music, and my imagination, I could escape the noise of family life.

Dad did all he could on a small income to make my bedroom a comfortable, beautiful place: he painted it maroon with white trim. He bought a secondhand dresser and headboard and painted them white. A horse poster and two glass lamps finished off the décor.

My dad used to sing songs to me at bedtime every night: “Casey Jones,” “Comin’ Round the Mountain,” “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” He’d always end with “Goodnight, Sweetheart.” In sixth grade I told some kids that my dad sang to me, and they laughed and called me a baby. That night, I told my dad I was too grown up for bedtime songs. “OK, then,” he said, “I’ll just kiss you good night.”

After he left, I cried myself to sleep.

Bonnie Gendron

Santa Ysabel, California

The bedroom is where my husband and I have had sex for thirty years. Sometimes we fuck, doing unspeakable things to each other in the dark. Other times we make love, clinging to each other because there is no one else in this world who understands.

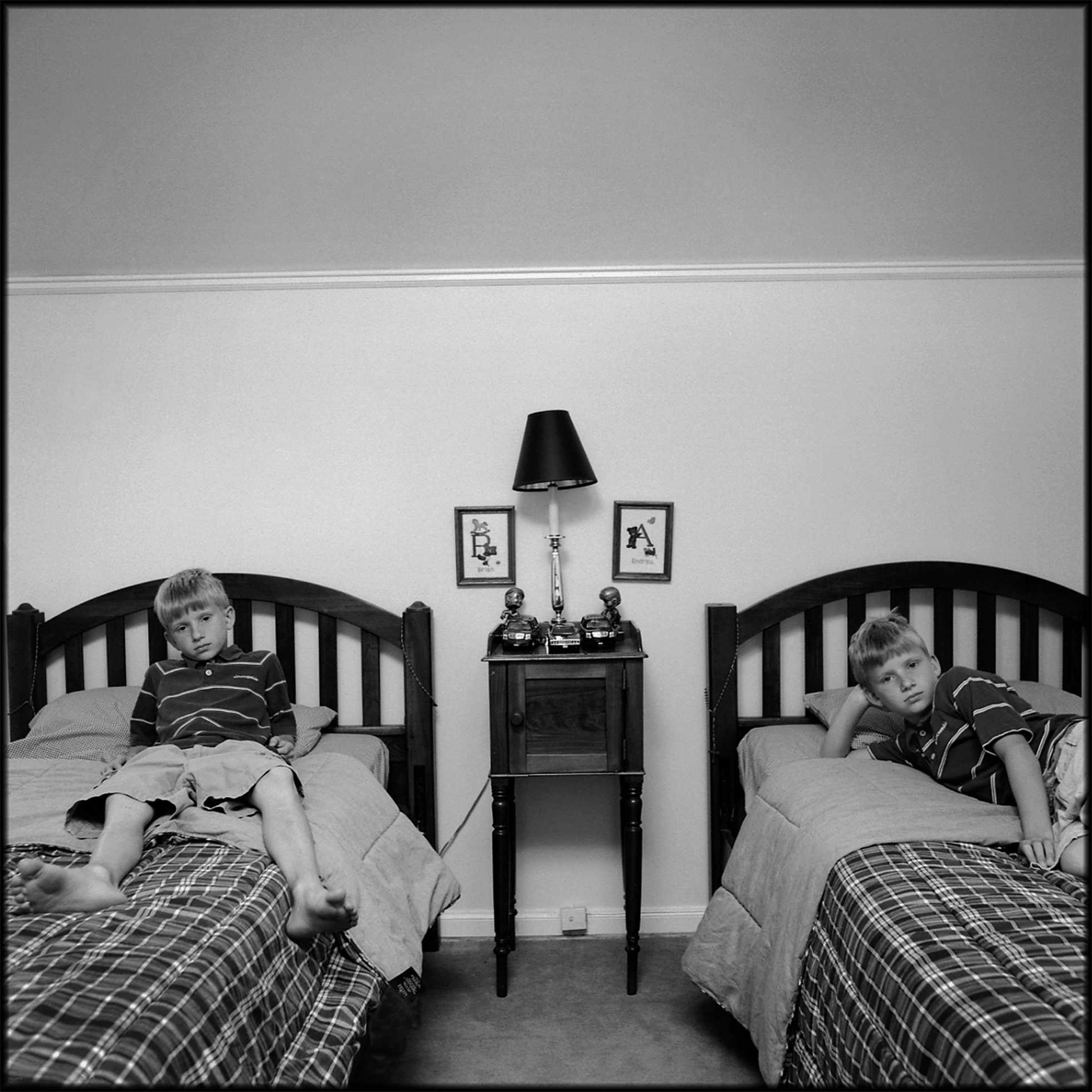

The bedroom is where I cuddled my newborns and gazed upon their scrunched-up faces, not knowing whether to cry, because they were so beautiful, or laugh, because they were so ugly. The bedroom is where I nursed my girls to sleep, their tiny lips trembling as I slid my nipple away and we became separate entities once more.

The bedroom is where my husband and I slept each night with our two girls. Sometimes their flailing and throwing up and whimpering kept us awake. Other times we just listened in the dark to their breathing, every inhale and exhale a confirmation: “I am alive.” Nothing else mattered.

Now the bedroom is where my teenage daughters come and lie down next to me and let me hold their hand as we talk. Sometimes the younger one still sleeps with me. Holding her in the dark, I can’t remember if she is six or sixteen, and it doesn’t matter. And when they both pad softly down the hall to their own bedrooms, my husband slides in next to me, his heavy, rough farmer’s hand between my breasts, pulling me close.

Name Withheld

He and I had been friends since we were teenagers and skateboarded together in the Kohl’s parking lot. Our friendship had often teetered on the brink of becoming something more, but we were always dating other people.

Now, almost a decade later, he and I went to a party while his girlfriend was visiting family in Wisconsin. When we came home together, it just happened: I marched past the futon in the living room and flopped onto his bed. He unzipped my leather go-go boots and peeled off my little black dress. It was wild, passionate, and fun. And it was only going to happen once. There was no way his girlfriend would ever find out.

He and I woke up the next morning laughing about it and agreed that it would be our little secret. But when his girlfriend returned, he promptly confessed. Later he told me she’d wanted to burn the bedroom sheets.

Our friendship quickly dissolved. The last I heard, he had finally put a ring on her finger, which is all she’d ever wanted. I believe he had to relieve the sexual tension with me in order to get on with his relationship. I was in the way, and now I’m not.

Mercy

San Luis Obispo, California

After living in a series of one-room studio apartments, I moved into a place with an actual bedroom. I kept all my furniture in the living room and set up the bedroom as a place to meditate. A small altar stood along one wall, and a zafu and zabuton (cushion and mat) occupied the floor. I started each day by lighting candles, bowing to the little statue of Buddha, then taking my place on the cushion. Buddhists are supposed to be beyond attachment to things, but I grew protective and possessive of my little personal zendo. I rationalized this by believing the zendo intensified my practice, but I knew it was as much about having my own private space.

When Paul, another tenant in my building, lost his job, he decided to move in with his mother. He asked if I knew anybody who could keep his furniture for a month. I immediately thought about my zendo. I wasn’t obligated to Paul. He’d never done me any favors. And I didn’t want to give up my beautiful meditation space. Still, I said, “I’ve got a little room.”

One month turned into two, then three. I meditated in the corner, surrounded by his boxes and futon. Sometimes I was angry at Paul for invading my space. Other times I was angry at myself for giving in so easily.

After another month, Paul found a place to live and asked me to drop off his boxes. “You can keep the futon,” he said. “I have a bed now.” After I delivered his belongings, I went back to my zendo and stared at the futon.

I decided to live with it, and I’ve even added an end table, a lamp, and a tall black vase. I still meditate in there, but I kind of like having a bed in my bedroom.

David Wood

St. Petersburg, Florida

After seven years of marriage, I have a bedroom to myself again. Gone are the arguments about whether to sleep with the blinds or the window open, where to set the thermostat, when to turn off the TV and the light, and in whose nightstand the rarely used body oil should reside. Gone are the skirmishes over who’s taking up too much of the bed and the nights of quiet desperation, unfulfilled desire, and angry silence.

Now I sleep diagonally and go to bed as late as I want. I wake up to daylight rushing through my open window and feel more refreshed than I have in seven years.

L. Braum

San Francisco, California

As a teen, I thought that if only my father could acknowledge the poorly kept secret of his homosexuality, he would be happy. His days of lying in bed, eating bowl after bowl of ice cream, would be over. He’d be available to be my dad. I dreamed of opening the windows in his room, taking away the dirty dishes, and throwing out the gay porn hidden in his closet. I imagined a new home with two fathers who unabashedly loved me and each other.

One night I came home early from a party and found my father’s bedroom door closed. When I knocked, he frantically implored me not to come in. I guessed right away he wasn’t alone.

Thinking I could catch him, I forced myself to stay awake, like a child waiting to see Santa. I would jump out of bed as soon as his door opened. But when I finally heard the doorknob turn early that morning, I was too tired to get up. Later I tried to joke with my dad about “interrupting something,” but he denied it.

My father now sleeps in a different bedroom, in his own apartment near our house. He still leaves dirty ice-cream dishes on his nightstand. I wonder sometimes what would have happened if I’d seen that person leaving his bedroom all those years ago. Perhaps my father would have introduced me, and we could have gotten to know one another over breakfast. More than likely, however, he would have denied everything and reached for another bowl of ice cream.

Name Withheld

When I was a child, I shared a bedroom with my mom, and my brother shared a room with my dad. I didn’t know this was strange until, in the second grade, I noticed that my aunt and uncle slept together in the same room.

On Saturday nights, after Mom thought I was asleep, she’d get up and go to the living room. “Oh, come on,” I’d hear her say. “Goddamn, just come on.” Then she would return to our bedroom with Dad. He’d take off his pants and get into her bed.

I never looked, but I would hear her bed creaking and the crucifix knocking on the plaster wall behind the headboard. The whole time she’d be telling my dad to “hurry up.” Eventually he’d let out a little sound like air coming out of a bike tire. Then my mom would whisper, “Get off. Just get off.”

My dad would get up, take his pants, and leave. My mom would get something out of her nightstand and go to the bathroom for a long time. When she came back to our room, she’d reach over to the plastic holy-water container hanging on the wall, wet her fingers, and make the sign of the cross, touching her forehead, chest, and shoulders. She was safe for another week.

Patty K.

Olympia, Washington

Sundays were the one day of the week our family business would close and our father would be at home. He was often so tired that he spent the entire day in his and my mother’s dark mahogany bed, a pack of Chesterfields, a book of matches, and an ashtray (usually full) on the bedside table, Harry Caray’s voice announcing a baseball game on the radio. Our always-polite dad thought nothing of loudly breaking wind in his sanctuary. This was his day of rest.

At the age of seventeen Dad had had his right leg amputated above the knee because of a severe football injury. He wore an artificial limb held in place by a wide leather belt secured around his waist. The prosthetic rubbed and irritated his stump, causing a rash. He had phantom pain. But in spite of this handicap, he was a champion swimmer and taught my brother and me to play tennis.

Dad’s body was sore most of the time. On those Sundays in bed, he would sometimes call me or my brother into the room and offer us a nickel to walk on his back. The room smelled of cigarette smoke and flatulence. Our small feet would press into his sheet-covered spine, buttocks, and legs, and he would moan and exclaim, “Jesus, that feels good!”

Other Sundays the drapes in the room would be drawn, and we would hear moans of pain coming from behind the door. Dad suffered migraine headaches that would last for hours, during which we tiptoed and spoke in hushed voices.

And then there were the Sunday afternoons when Mother would go into their bedroom and close the door. She would already have read the newspaper and fed us lunch. At a certain age I began to understand they were doing something other than napping. My brother and I would creep as close to the bedroom door as we dared and listen; or we would go outside and try to peer in through the window. My parents were discreet, but we knew.

Carol Shapiro

Bloomington, Indiana

I think I married him because he was safe. He was totally head over heels about me, so he was not going to leave. He didn’t have an explosive temper, like my dad. He didn’t have a tendency to drink too much, like my first love. He wasn’t weirdly dependent on his parents, like my second love. He adored me. I think deep in my genes I knew he would make healthy, gorgeous children with me. After years of passionate sex with crazy, undependable men, I think I made myself stop when I found him, told myself he was the healthiest choice for me.

And in the bedroom, now many years into our marriage, I tell myself that feeling tenderness for him has to be enough.

Name Withheld

Our bedroom was a place to sleep, read, and make love. Then Len began waking me in the night to help him turn over. He’d be thrashing about and pulling at the covers in frustration.

We avoided talking about this frightening nighttime ritual until he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. We could no longer pretend it wasn’t happening. As Len’s disease progressed, our bedroom became a hospital room, a battleground.

Parkinson’s robs people of control over their muscles; so, in addition to the gymnastics, Len drooled on his pillow. One of his medications made him laugh out loud in his sleep. His body became more rigid, slowly turning to stone, and his arms around me in bed were like a vise.

After Len died, I began reclaiming the bedroom. I painted the walls lavender, hung some pictures, and bought a floral duvet cover. I also began sleeping on his side of the bed. Now, when the sheets need to be changed, I switch to my old side, where I reach across and pat his, as if he were still there. Though my sisters have stayed with me in our bedroom, I haven’t let anyone else sleep on his side of the bed.

Lorna Reese

Lopez Island, Washington

When I was a boy, I shared a bedroom with my younger sister, who’d been born with a heart defect. Doctors predicted she would die before her tenth birthday. I was frequently reminded not to upset her, and my parents treated her like a porcelain doll. She rarely left the house, was not permitted to exert herself or perspire, and did not even go to school. On weekend mornings my sister would crawl into my bed and cuddle up against me, and we’d talk for hours. She’d ask what school was like or how my team had done in the intramural soccer game.

As my sister’s condition worsened, my electric train and sporting goods were moved out to make room for oxygen tanks, bottles of medications, space heaters, and dolls sent by relatives. When I complained to my mother that I was being squeezed out, she said sadly that the room would be all mine soon enough.

One Friday I was sent to spend the weekend with my favorite aunt. On Monday morning, as my father drove me back home, he told me that my sister had died. She’d been buried during my absence, to spare me the shock and grief. I was stunned. I hadn’t been spared the shock and grief, nor the guilt.

When we got home, I went straight to my room and closed the door. My sister’s bed was neatly made. All her dolls and medical paraphernalia were gone. The room I had longed to have to myself now seemed barren and lonely. I sat on my bed for hours, staring at her empty one, not even realizing that I was crying until I felt my wet cheek.

George Constantinidis

Alexandria, Virginia