My authoritarian father ruled our house, and long after I left home, I continued to hear his voice. All the negative things he had ever said about me still colored my perception of who I was.

After I got married, my mother-in-law welcomed me into her heart and helped me feel better about myself. She had become a widow at a young age and had raised seven children alone. I tried to emulate her strength and resilience.

When my own daughter grew more independent, she decided to get an eyebrow ring. Watching her undergo the procedure at a tattoo-and-piercing parlor, I thought it would be symbolic to have a small butterfly tattooed on my ankle as a reminder that I was free from my past. So I did.

That evening we had a family gathering, and someone told my mother-in-law that I had just gotten a tattoo. She looked at me sternly and said, “I do not approve.”

I found the strength to reply, “Luckily I did not do it for your approval.”

At that moment I knew I had stopped worrying about other people’s opinions.

R.B.

Bamberg, South Carolina

I quit high school during my sophomore year to marry James, a seventeen-year-old itinerant worker. The year was 1959. Not long after the wedding James heard there was work in New Mexico, where his parents lived. So we drove to Las Cruces and stayed with my in-laws, who were living in a two-room cabin at a run-down motel on the edge of town.

James’s parents, Betty and Charles, had left Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl and picked cotton, grapes, walnuts, and other crops in California. Now Charles worked construction across the Southwest. Betty was small and wiry, with a dark complexion and thick gray-brown hair cut bluntly around her face and neck. Charles was short, muscular, and bowlegged, with a sunburned face from working outdoors his entire life. Both seemed old to me, but I was just fifteen; everyone over thirty seemed old.

The morning after our arrival, my husband and father-in-law got up early for work. Before they left, Charles gave me a dollar bill and told me it was for Betty’s beer, but not to give it to her before 5 PM. This seemed like a strange request, but I didn’t feel it was my place to ask questions. The men drove away, and I was alone with Betty for the day. I had recently gotten pregnant, so we walked around Las Cruces looking at baby clothes and furniture. I didn’t have money to purchase anything, but Betty cooed over the little dresses and knit blankets. She asked what we would name the baby and gave me advice on childbearing, which sounded scary and difficult. She was the first person to talk to me about the realities of motherhood.

After we’d returned to the cabin, I talked Betty into letting me wash and set her hair. Like a girl playing beauty shop, I put her hair in rollers, then combed and styled it. Betty seemed to enjoy the attention even though, when I was done, she looked much the same as before.

Next I went to the bathhouse in the courtyard to take a shower. (The cabin had no hot water.) Betty came with me and stood outside the door holding a broom in case anyone tried to barge in. I wasn’t sure there was a threat, but I was glad she was there all the same.

By midafternoon Betty was asking me for her beer money and accusing me of wanting to keep it for myself. Remembering my father-in-law’s instructions, I held out as long as I could, but she became increasingly demanding, and around four o’clock I gave in. We went to a nearby bar, where she chatted with the bartender and drank her beer. I had a Coke. Afterward we walked home and fixed supper: beans, biscuits, and hot coffee.

James and his father arrived around six, exhausted and covered with cement and dirt. After supper Charles and Betty drank more beer until they were both drunk. James and I slept on the couch while they argued in the bedroom.

In the middle of the night Betty came into the living room with a paper bag she had lit on fire, screaming and threatening to burn the cabin down. Charles staggered after her. James jumped up, put the bag in the sink, and doused it with water. Then he yelled at both of them to go to bed. Before retreating to the bedroom, my father-in-law urinated in a drawer, thinking it was a toilet. I was terrified, disgusted, and confused. While my husband fell asleep, I lay awake wondering what I had gotten myself into.

I can now appreciate Betty’s kindness. She took me in, accepted me, and mothered me at a time when I was feeling vulnerable. She and Charles had lived harsh lives but were generous with us, sharing food, money, and a place to live. They did the same for neighbors and even strangers. But at that time I couldn’t see this.

Five in the morning came too soon. Betty made a hot breakfast, and my husband and father-in-law changed back into their dirty work clothes from the day before. No one commented on the blackened pieces of burned bag on the floor. As my father-in-law was going out the door, he handed me another dollar bill and said, “Don’t let her have her beer until five.”

S.M.

Conifer, Colorado

During the first year Bill and I were dating, he was not out of the closet to his family, who knew me only as his “close friend.” Bill’s mother and I shared recipes and talked on the telephone with great frequency. In private Bill joked that his mother loved her new “daughter-in-law.” (We later learned that she had guessed our true relationship.)

About two years after we met, Bill’s paternal grandmother died. The funeral was held in a small country church, and Bill was a pallbearer. Afterward, at the burial site, I stood in the back so as not to intrude. His extended family didn’t know me well.

There were about four or five rows of people around the grave, and Bill was at the front. As the preacher began the service, I saw movement in the crowd. To my amazement, Bill’s mother was headed straight toward me. She grabbed my hand and pulled me through the mourners to stand right next to her and her husband.

Twenty-eight years later, when same-sex marriage became legal in Massachusetts, Bill and I made our bond official, but with that one simple action long ago, his mother had already declared me a member of the family.

Chuck Fiorentino

Washington, D.C.

I never particularly liked or respected my wife’s younger brother. As far as I was concerned, Paul was a boring introvert. His appearance was slovenly, he always missed a few spots shaving, and an ill-fitting hairpiece covered his bald spot. He was a high-school guidance counselor, though I couldn’t imagine him providing helpful advice to anyone. Whenever I’d ask him anything, I’d rarely get more than a one-word answer, unless my question was about sports. Little else seemed to interest him.

After his wife’s death in 1980, Paul’s closest relatives — other than his mother — were his nephews, my sons. He’d take them to see the Cleveland Indians play, or the Cavaliers, or the Browns. Needless to say, Paul was my boys’ favorite uncle.

Paul died unexpectedly two summers ago at the age of sixty-three. His death was especially hard on my grown sons, who had already lost their mother and their grandparents. We muddled through the funeral arrangements with the help of several of Paul’s good friends. I figured there wouldn’t be much of a turnout, but his friends believed otherwise, so we found a space that could accommodate two hundred or so.

Nearly five hundred people showed up, most of them students who had come to Paul for advice over the years. The funeral home opened additional rooms, and the overflow crowd stood in the hallways. Afterward there was the receiving line and a dinner with an open mike for anyone who wanted to reminisce about Paul. One man said Paul was the reason he had stayed in school, and he was now a medical doctor. Others shared similar stories of how my brother-in-law had helped them find the right path in life. They described a Paul I’d never known, because my judgmental nature had prevented it. It was my loss.

Michael Barnes

Aurora, Ohio

My high-school boyfriend’s parents were conservative Christians, and I was a bold teenager, proud of my feminist ideas and vegetarianism. My own parents had not raised me to believe in any religion.

I’m sure I was not the kind of girl my boyfriend’s parents wanted their only son to date, but they greeted me warmly and smiled politely when I refused meat at their table. They even discussed animal rights with me. (My boyfriend’s father worked as a consultant for the fur industry.)

One time my boyfriend’s parents caught me straddling their son in my homecoming dress. And that wasn’t the only occasion when they found us in a compromising position. Once, my boyfriend’s mother yelled at us, “You play with fire, and you’re going to get burned!” Thirty minutes later, however, as I tried to sneak out of the house, she stopped me and said she and her husband loved me no matter what, and I was always welcome in their home.

At the age of twenty-five I married their son. I now feel closer to his family than I do to my own. I’ve learned that in the past my in-laws prayed fervently each night that their son would marry a girl who shared his Christian values, but they never once asked me to change or expressed disappointment that I wasn’t a Christian. They simply loved me and had faith that God knew what he was doing.

Shelby Riley

Downingtown, Pennsylvania

There’s an old Vietnamese proverb: “Always marry an orphan.” I learned its wisdom when I married into a large Vietnamese family.

My in-laws were traditional Confucians who highly valued family roles and responsibilities. By custom a Vietnamese wife severs ties with her own family and belongs entirely to her husband’s parents. This was a challenge for me as an American to accept, especially after my mother-in-law came to live with us. She was stubborn, petty, and argumentative, yet I was expected to respect and obey her. Her own experience as a daughter-in-law had not been good, and it seemed she had decided to pass along the misery to me. Nearly every day she instigated arguments that shook our home. Finally I decided to move out. I gave my husband an ultimatum: he could either come with me or stay with his mother. After much discussion he remained with her.

Our separation lasted for years, but eventually his mother went to live with her daughter in France. Although my husband and I reunited, I still resented the choice he had made.

One day, while feeling frustrated with him, I realized something I hadn’t before: that by fulfilling his duty as a son to care for his mother, whom he could barely stand, my husband had demonstrated strong character. Would I really have wanted to marry a man who would desert his mother — even for me?

Name Withheld

Kevin and I married at nineteen. We thought we were in love, as we understood it at that age, but our greatest similarity may have been our social awkwardness and fear of dating.

Fifteen years into the marriage I met and fell in love with someone else. The divorce was difficult for our two children and our extended families. I was cast as the villain for a while, but in time even my former in-laws came to like my second husband.

Another fifteen years later, on a spring afternoon, I was pulling weeds from the front lawn when my cellphone rang. It was Alice, my former mother-in-law. Now that my children were grown, I rarely spoke to her. I sat on the grass as Alice explained why she had called.

I knew her husband had died about six months earlier after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s. During his decline, Alice said, she had joined a support group for caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients, where she had befriended a man named Frank. When both their spouses died around the same time, the friendship quickly became a romance. In the eyes of their children, however, it was too soon after the funerals.

“I called you because I thought you would understand,” Alice said. “My kids don’t want to hear about it, but I knew you would be happy for me.”

And I was happy for Alice, who seemed giddy at the unexpected reappearance of love in her life. I was also amused by the irony: what had once made me the family villain now made me a sympathetic ear.

Name Withheld

When I met Dan, I was a widow nearing fifty, and he had been married and divorced. We shared a love of nature and took walks together in the shadows of ancient cedars and towering Douglas firs.

I grew fond of Dan’s parents, Jim and Peggy. Although he and I never married, for fifteen years they treated me as if I were their daughter-in-law. Visits always began and ended with hearty hugs from them both. “My father must really like you,” Dan said at one point. Jim wasn’t usually affectionate, even with his own children.

Once Jim learned that I liked gardens, each trip to their house came to include an hour-long yard tour, in which we stopped by each new plant, and he would tell me its story. He delighted in showing me volunteer seedlings he’d rescued and replanted. For Jim’s eightieth birthday I gave him an unusual hydrangea, and it flourished under his care.

I’d thought that Dan and his parents would be in my life forever, but two years ago Dan told me he was having an affair. Torn between loyalty to their son and affection for me, Dan’s parents chose him. Suddenly I was treated like the “other woman.” I did at least receive condolence letters from Dan’s three siblings and from his mother. I heard nothing from Jim.

A year after the breakup, Dan’s sister and mother asked me to lunch. I drove eighty miles to meet them at one of his mother’s favorite restaurants. Our initial greetings were awkward, but we soon fell into our old banter. I fought back tears all through the meal. We did not speak of Dan’s new girlfriend.

After lunch his mother said she had something for me in her car. I followed her to the parking lot, and she opened the trunk. There was a tiny potted hydrangea bush — an offspring of the plant I’d given Jim years ago.

“This just sprang up in the yard,” she said. “Jim wanted you to have it.”

I planted the hydrangea that day, not expecting it to bloom for another year. That summer it produced three huge white flowers that lasted for weeks.

Name Withheld

My husband and I were both visual artists and liberals. His mother was a staunch Republican who could find the negative in any situation. Nothing we did pleased her, because nothing about us was proper or conventional.

I dreaded trips to see my mother-in-law. After about an hour with her, my husband and I would retreat into the guest bedroom of her all-white, perfectly kept house and collapse on the bed. We cherished any moment away from her incessant complaints concerning the neighbor’s unsightly building materials or the noisy kids in the schoolyard adjacent to her home. Throughout our visit she voiced disapproval that my three-year-old daughter couldn’t sit still. She told terrible stories about my husband’s favorite aunt and uncle, and she had acid-tongued arguments with her gloomy second husband. I had little if any affection for her.

It’s been seven years since my ex and I divorced, but I still see my former mother-in-law every Monday afternoon. I travel across town to the memory-care unit of her retirement community, where I always find her slumped in a wheelchair. Her once perfectly painted nails are ragged and short. Her hair is no longer coiffed, and her designer wardrobe is overwashed and faded.

When she sees me, she squeals, “My lovely daughter!” She repeatedly speaks of her impending wedding to a handsome astronaut: Someone has to pick up her dress from the seamstress. Her fiancé loves her very much, but she can’t quite remember his name — she’ll think of it later.

Dementia has erased any trace of the miserable, negative woman I once knew. All that compassion I could not find for her then, I feel now as I sit with her and listen.

C.C.

Portland, Oregon

My mother-in-law, Margaret, had raised seven sons. Widowed and nearly eighty, she still seized every opportunity to offer her opinions about the importance of style and order in life. I was intimidated by her.

One afternoon, while Margaret was visiting, I excused myself to run errands. (She’d assured me she could take care of herself.) On my return I found her in the kitchen preparing supper. Since she loved to cook and I had no dinner plans, I could hardly complain. So I went to the living room to tidy up.

When I got there, I found the entire room — including our seven-foot-long couch, two overstuffed wing-back chairs, two end tables, a wrought-iron coffee table, and my piano — had been rearranged. My mother-in-law had single-handedly moved every piece of furniture into its new place.

“Isn’t that so much better, my dear?” she called from the kitchen.

N.T.

Lynden, Washington

Each year my wife and I spent a week in the country with her family. We would hike the trails, prepare meals together, and drink beer. All the men in my wife’s family were conservatives, and my wife and I were liberal. Social and political discussions could get heated, especially after the second or third beer. My mother-in-law, a quiet woman with a strong presence, always played mediator, trying to cool tempers or redirect the conversation before an argument got out of hand. A couple of times, when my wife tossed a sharp barb my way, I caught my mother-in-law’s eyes saying, Sorry.

My wife’s mother was a crackerjack bridge player and patient with my novice attempts to be her partner. She passed on to me her love of bird-watching. I was about as good at it as I was at bridge, but she didn’t mind.

After my mother-in-law died, I realized that I shared more with her than I did with anyone else in the family, including my wife. We all continued going to the house one week out of the year, but it just wasn’t the same. She had been the gravitational force that held the family together; without her everyone seemed to drift.

I eventually realized that I had been drifting in my marriage for some time. During the divorce I often thought of my mother-in-law. I believed she would have been disappointed, even heartsick. I imagined seeing her eyes, moist and saying, Sorry.

Daniel Budd

Cleveland Heights, Ohio

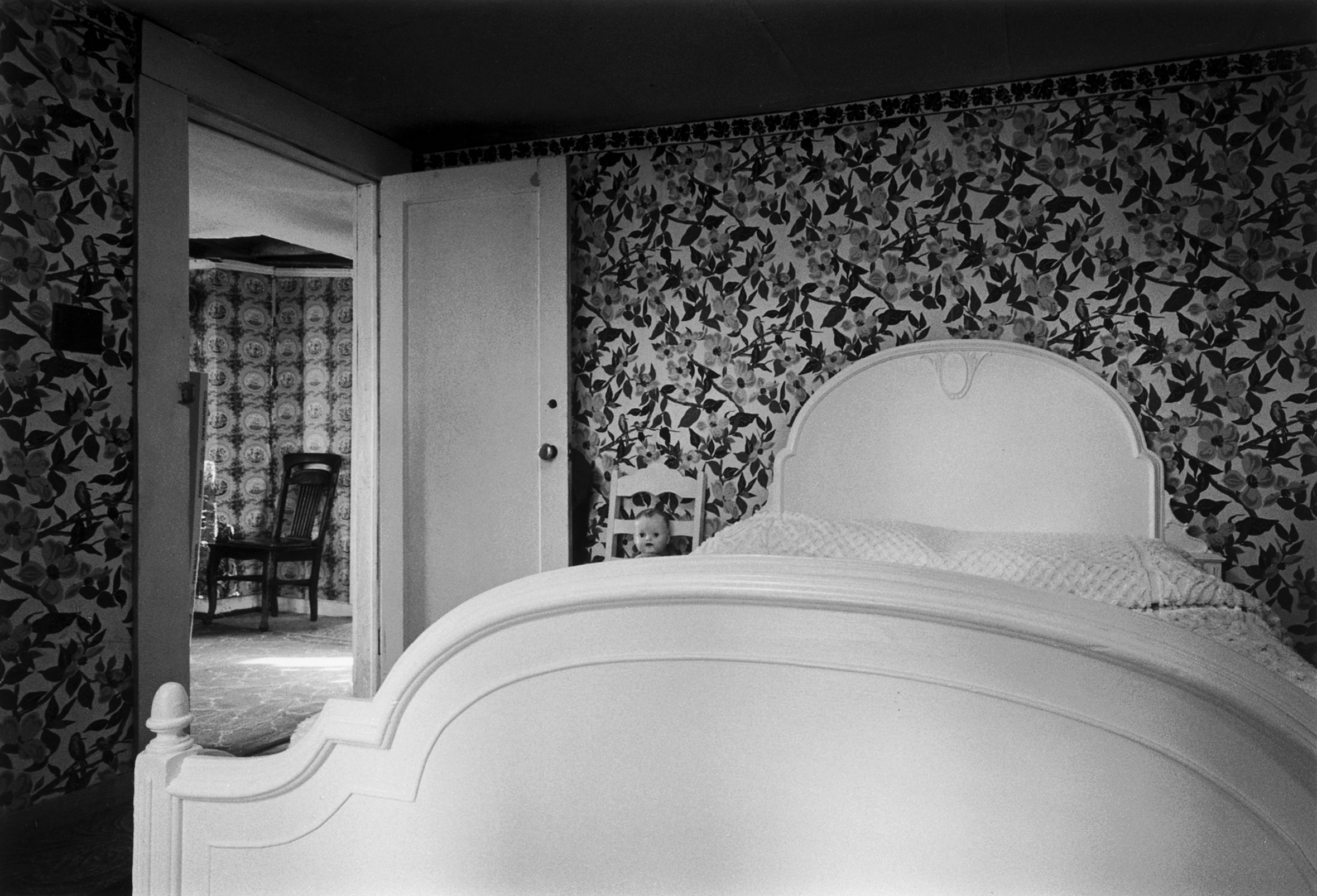

My husband’s Southern mother has a habit of delivering platitudes in a singsong tone, like a preschool teacher. “Spare the rod, spoil the child,” she might say. These phrases, though always spoken with a smile, leave me feeling judged. She will never think I’m good enough for John, her only child, the golden boy whose every piece of artwork and childhood toy is preserved in his old bedroom as if it were a museum. We sleep there every Christmas, and photos of my husband — from rosy-cheeked baby portraits to yearbook pictures with bad hair — peer down on us as we lie in bed.

I thought I would be redeemed when I gave my mother-in-law a grandson, but somehow my boy doesn’t quite measure up either. “John never had tantrums like that,” she’ll say as I carry my flailing child out of the living room. Or: “John was using a spoon when he was six months old,” as my child throws his food on the floor with a devilish grin.

The one thing I enjoy about these Christmas visits is setting up the village — a collection of porcelain houses and figurines — beneath the tree. My husband and I have a tradition of making additions to the village, always trying to outdo the year before.

This year the boxes containing the village are out and near the tree, ready to be unpacked, when I leave for a yoga class. I haven’t done this before at my mother-in-law’s — leave to take care of myself — but I need this to preserve my sanity and keep the holiday spirit. The class is rejuvenating. Afterward I feel prepared to face whatever lies ahead. Maybe I’ll even help my hard-to-please mother-in-law in the kitchen.

When I walk through the door, I see the village under the tree, completely set up. I’m crushed.

“There are consequences to every action,” my mother-in-law says with a smile as she dries a dish.

It takes all the restraint I have not to run across the room and smack her in the head with my yoga mat.

I go to the bedroom, where the images of my husband at different ages stare at me. In the middle of my misery I realize: This is why I am here — to be with the man I love. And, God help me, she is his mother. Determined to make the best of it, I sit and do lovingkindness meditation, widening my circle of compassion to include those I find hard to love.

When I come back to the kitchen, I offer to help my mother-in-law cut up a pineapple: a complicated process involving multiple knives that I can never seem to get right. I try to extend love to her without condition or expectation. Her face seems to soften just a little.

“Many hands make light work,” she says.

Someday I hope my heart will open easily to my mother-in-law. I’m not quite there yet.

K.W.

Lafayette, Colorado

My British mother believed hugging friends was a low-class American custom. We seldom visited relatives, and even close family members sometimes went years without speaking to each other. So when I got engaged to Dick, I was not prepared for how openly his parents expressed affection.

When I met Louise and Phil for the first time, they kissed me on the lips. I was still recovering from the shock as they steered me into their cluttered living room, where family and friends were gathered. Louise handed me a steaming dish of casserole topped with deep-fried onion rings, and Phil poured me a glass of cheap wine.

“It tastes better with a little vino,” Louise said, splashing more into my glass, which I later discreetly emptied into a planter — only to have Phil immediately refill it.

“You’re like one of my daughters,” he gushed, his arm around my waist.

No, I’m not, I thought, watching one of my future sisters-in-law run her fingers through her mother’s hair.

Every Christmas, Thanksgiving, and Easter, Dick and I drove six hours to visit his relatives. It took me years to learn everyone’s names and relations to each other. “Dicky,” as they called my husband, was a taciturn man, but at his parents’ home he laughed with gusto, hugged his aged aunt, and listened patiently to his nephews’ plans to build solar-powered go-karts. Dick had told me that as a teenager he had knocked his father over a table and broken his nose, then run away from home and lived in his car for six months. When I asked Louise about this, she smiled and said, “I don’t remember anything about that.” She slurred her words a bit, even when she wasn’t drunk. “My children are perfect,” she often said.

I left Dick after fourteen years because he’d begun hoarding guns and stealing my paycheck to buy gold coins. I haven’t talked to my in-laws since the divorce, but I believe if I showed up at Louise and Phil’s house today, I’d be welcomed with a sloppy kiss on the mouth and a glass of fruity, chilled white wine.

Dion O’Reilly

Soquel, California

At dinnertime my partner, Steve, joined me at his parents’ kitchen table. I sat closest to the wall, feeling especially withdrawn and shy. My in-laws’ Midwestern manner was so different from mine. I ached to have an honest conversation with them and didn’t understand the unspoken rules of dinnertime. Having to speak of the weather and the day’s business was difficult for me. I wasn’t used to holding everything in. But this wasn’t the time to think of my own needs. I was here for Steve.

Steve didn’t seem to notice my discomfort as he reached for the salad bowl. His mother, Rose, was busy cutting the pork roast and pulling the broccoli from the microwave. My father-in-law loaded a piece of bread with butter and arranged a napkin on his lap. I focused on bringing food to my mouth, afraid that I would forget my manners and cry out, Why doesn’t anyone talk about anything real in this family? What the hell is wrong with you people?

I didn’t want to chitchat about the route that Steve and I had taken to the library that day. I wanted to talk about what we were all avoiding, to say, Steve has cancer, and I am scared to death.

Name Withheld

When my father heard I was dating a Middle Eastern man, he sent me the DVD of the film Not without My Daughter, the story of an American woman who fights to get her child back from her Iranian ex-husband. When my boyfriend, Maroun, sent photos of me to his mother in Lebanon, she said, “An American woman will divorce you and steal your children.”

Both parents meant to protect us, but both had watched too much television.

When Maroun and I got engaged, I worried that our respective in-laws would be unable to see past their preconceptions of us.

When I finally brought Maroun to central Florida, my dad saw how my fiancé placed his arm protectively around my shoulders, and he listened as Maroun spoke proudly about completing a recent marathon. “He seems to be a real good guy,” my father told me after the visit.

I worried about meeting Maroun’s mother, especially since she and I didn’t speak the same language, but over the course of a week in Beirut, I began to relax. She prepared marvelous meals, and as we became more familiar, she would touch my abdomen and ask, “Je’aaneh?” (Hungry?)

“Eh,” I would answer. Yes.

“The American can eat!” she would say to her son, who translated for me.

Just as quickly as they had prejudged us, our in-laws accepted us. All they needed to do was meet us in person.

Elizabeth Kelsey

Lebanon, New Hampshire

I was nineteen and having dinner with my boyfriend’s family for the first time. This was a big step. He had never brought a girl home for dinner before.

It was the early 1970s, and we had fallen in love at college, where we were both involved in the antiwar movement. But now we were in a working-class New York City suburb. This was Richard Nixon country, and I didn’t know how to act.

Six of the seven members of my boyfriend’s family gathered in the cramped dining room. There was an air of stiff formality: frilly napkins, lacy tablecloth, heavy silverware. My future father-in-law was seated at the head of the table. I had heard enough stories about him to feel apprehensive, and I was intent on being my charming best.

The main course was a deep-dish casserole of gray ground beef, raw onions, and still-frozen peas, the whole mess barely warm at the center. My boyfriend’s father sat with a large screw-top bottle of cheap red wine in his hand. Instead of walking around the table and pouring each person’s glass, he stayed in place and asked, “Do you want any?” as if daring each of us to say yes.

The conversation was about the weather, the garden, the miserable morning commute. My boyfriend’s father would complain about one of his carpool buddies, and his mother would reply with a comment about the spirea bushes in the yard. It was as if no one heard a word anyone else said.

We were just about to finish dinner when someone mentioned the actor John Wayne. I whispered to my boyfriend with disdain that Wayne was a “love-it-or-leave-it” type, referring to the right-wing Vietnam War–era slogan “America: love it or leave it.”

What happened next still makes me quiver. My boyfriend’s father’s fist hit the table, and he roared, “I fought in the war, and some of my best friends died there. Don’t you dare bring that attitude into this house!” Then he got up and left the room. No one looked up from the cold casserole before us. Stunned and embarrassed, I made my way as quietly as possible to the door. I didn’t even say thank you for dinner. I just wanted to disappear.

As I drove home, I thought, That went well.

Erika Guy

Huntersville, North Carolina

My in-laws’ Mormon church teaches that a marriage is between one man and one woman. When my wife, Monte, told them about our relationship, they listed for her the three greatest sins: murder, denial of the Holy Ghost, and homosexual behavior. (Monte and I are both women.)

Monte said that if they wanted to see her, they would have to consent to see me as well. It took them more than a year to agree.

Now we visit my in-laws often, and we’ve discovered that we share many interests. Monte and her father compare notes on maintaining chicken coops through northern-Utah winters; Monte’s mother and I exchange recipes for pickled beets and canned pears. Of course, differences remain. They say grace before meals; we express gratitude for the earth and our children and each other. But, beneath the surface, I believe we share an appreciation for what’s good in our lives. I think that, as I’ve learned from Monte’s parents how to store food for the long Utah winters, they have learned from us the value of our love.

Each time my mother-in-law leaves a message on our phone, she ends by saying, “Love to you both.” Whenever my father-in-law and I greet one another, he offers me a firm hug. Last Sunday they came to our house for lunch. As Monte and I served the meal, my father-in-law said, “You have a wonderful home.” It felt as if he meant more than the furniture and appliances.

I’m not sure what my in-laws think of the recent ruling in Utah that permits marriage for same-sex couples. Discomfort prevents me from asking. But I’m thankful that my mother-in-law was comfortable asking Monte and me for something the other day. She said that they had photos of all their other children and their spouses on the mantelpiece, but they didn’t have a picture of Monte and me. She was wondering if we could spare one.

Felicia Rose

Hyrum, Utah

My new love and I rode by motorcycle to Southern California to visit his family and friends and tour his old stomping grounds. Being introduced to everyone made me nervous. I was recently divorced from a man whose family had never quite accepted me. I’m afraid to say I was a little relieved that my boyfriend’s parents were both dead; at least they couldn’t reject me.

At the end of the first day, we were riding lazily through suburbs when, unannounced, my boyfriend pulled into a cemetery. He led me by hand around the headstones. Stopping in front of one, he sat down and drew me to sit next to him. “Mom, Dad,” he said, “I want to introduce you to someone very special.”

Theresa Holland

Indianola, Washington

I got married in 1992, and for twenty years I chuckled and shook my head at the greeting cards my father-in-law sent me. Without fail he would address me as his “daughter” in quotation marks: “Happy birthday to a most remarkable ‘daughter.’ ” It was a persistent reminder that I wasn’t quite the real deal.

Last year my husband decided to move out, buy his own house six miles away, and start going to the gym and running races. He wanted to see our two children only one night a week and every other weekend.

For the first time in more than two decades, the birthday card I received from my father-in-law said how proud he was to have me as a daughter — no quotes.

J.H.

Bath, New York

As a boy in India I wondered why my family treated my aunt Bea with great deference. I had figured out that she was not really my aunt. So why did she have such special status? It took me fifteen years to extract the story from my mother.

Bea had grown up next door to my uncle Sudhir in the late nineteenth century. The two of them were just three months apart in age, and their mothers joked that they would someday marry and unite the two families.

As children Bea and Sudhir were close friends, almost inseparable. After they were grown, Bea went to college to study literature, and Sudhir went to medical school. At his graduation a British army officer came to speak. The army was badly in need of doctors to serve in the Boer War and was offering a handsome bonus and a generous severance package to anyone who would sign up for two years. Thinking he could use the money to set up a private practice in his hometown after the war, Sudhir joined the army and was sent to South Africa as a cavalry regiment’s physician.

Eight months later Sudhir’s regiment was traveling through a mountain pass when it was ambushed and wiped out by the Boers. My uncle was shot in the thigh, fell under his horse, and lost consciousness. When he came to, he was the only one left alive in a field of cadavers. He removed the bullet from his leg with a scalpel, gathered medical supplies and provisions, and took refuge in the bush. Walking only by night, he eventually found his way to a hamlet, where a farmer took him in. After several weeks he’d recovered enough to travel to a larger town and make contact with the British command. He spent four months in an army hospital before being discharged back to India.

Meanwhile, because Sudhir’s entire regiment had been reported killed, the army had paid compensation to his parents, my grandparents. Bea, believing her betrothed to be dead, had married the local school principal just a month before my uncle’s return. Though a misunderstanding had prevented Bea from marrying into the family, my grandmother insisted that she should forever be regarded as her daughter-in-law and invited to all family gatherings.

When I played soccer on the school grounds as a boy, I could see the principal’s residence from the field. Many afternoons I would spot Bea serving tea on the terrace to two men: the principal on one side and Uncle Sudhir on the other.

Manish Nandy

Reston, Virginia

From the day I met my in-laws, the walls were up between us. They spoke only to my husband, referring to me in the third person and never addressing me by name. It seemed nothing I did was good enough for them, no matter how hard I tried. I was the woman who had taken away their son. (As the mother of a married daughter, I now know what this feels like. I do call my son-in-law by name and acknowledge his existence, but when he became my daughter’s husband, it changed my relationship with her.)

Years later my mother-in-law had a serious heart operation. We didn’t know if she would come out of it alive. I offered to stay at the hospital through the night so that my husband and his father and brother could get some sleep. “No” is all my father-in-law said. Once again I felt the walls had gone up.

My mother-in-law survived the surgery and was transferred to a nursing home. She was intubated and could not speak or get out of bed. I didn’t think she wanted this kind of life.

The last time my husband and I visited her, she appeared miserable. Her exhausted husband hovered over her bed, and she wrote a message to him on a sheet of paper. He was visibly shaken and tearful after he read it. I was standing in the corner, and when my mother-in-law looked over at me, our eyes met. I approached her bed and leaned in to see what she had written to her husband.

“Please, let me go,” it read.

Then my mother-in-law turned the page over and wrote to me a single word: “Men!”

I began to laugh, and she smiled. The walls were finally down.

Anne Scherer

Rochester, Minnesota

Four years ago my girlfriend moved from Massachusetts to Iowa to live and work with me on a communal organic farm. Her parents were skeptical. They thought we should be engaged before she took such a drastic step.

Two months after her arrival I proposed at the top of a hill on a sun-drenched, snowy March day. That night we lay in bed joyfully planning our wedding.

When my girlfriend’s mother heard that we wanted to be married in Iowa, she was distraught. Some elderly family members would not be able to come because of the distance, she said. My fiancée spent several tear-filled hours explaining to her mother why we wanted to marry in the Midwest: so that both our families could see this beautiful place and meet the people with whom we lived. Eventually my future mother-in-law accepted our decision and began telling her friends that it was a “destination wedding.”

When the big day arrived, it was overcast and chilly, but everyone was in good spirits. During the reception at the farm, we heard that the first killing frost of the season was expected to come that night. Hoping to save our crops, we decided to ask the guests to help bring in the harvest. The tensions of the previous months were still fresh in my wife’s mind, however, so we asked her parents’ permission first.

“Sure,” my father-in-law said. “Just make sure you tell everyone it’s an Iowa wedding tradition!”

Minutes later the bluegrass band was serenading us as we worked, our anarchist friends in flannel shirts bending over beside extended-family members in suits and heels, everyone gleefully peeling back dead vines to pick squash and pumpkins. It was the highlight of our wedding. Some of my relatives even believed it was an authentic Iowa tradition.

We have a photograph from that day in our bedroom: my wife is standing between her parents, who are each holding a dirt-speckled butternut squash and smiling.

Eric Anglada

La Motte, Iowa