“Hidden amid the towering peaks of the eastern Himalayas,” photographer and filmmaker John Wehrheim writes, “Bhutan is the final outpost of the rapidly disappearing Tantric Buddhist culture that once guarded the Roof of the World. Tibet, Ladakh, Mustang, and Sikkim have all fallen to conquest or cultural and economic colonialism, while Bhutan — never conquered, never colonized — remains the last jewel in Buddhism’s Himalayan crown.” Nestled in an isolated region between India and China, it’s also a country transitioning from monarchy to democracy and from the Middle Ages to the twenty-first century. Since television was introduced to Bhutan in 1999, modernization has made inroads there. The country is struggling to strike a balance between engagement with the rest of the world and preservation of its ancient traditions.

Wehrheim first came to Bhutan in 1991 as a consultant in hydropower, the country’s largest industry. His work gave him access to people and places he says would have been denied to him as a photographer. After he exhibited some of his photos from Bhutan in 2002, he was approached by PBS filmmaker Tom Vendetti, who convinced Wehrheim to partner on the 2004 documentary Bhutan: Taking the Middle Path to Happiness. The film won two Emmy awards. Many of the photos here, all of them taken between 2002 and 2005, appeared in the accompanying book, Bhutan: Hidden Lands of Happiness.

In the early 1970s Wehrheim also spent time in Dharamsala, India, where he taught at the Dalai Lama’s school for Tibetan refugee children, and freelanced for The Tibet Journal. On assignment for The Journal, he trekked into the Tibet-Nepal borderlands, where he photographed farmers, herders, and monks and encountered Tibetan guerrillas. During this time he met Jamyang Norbu, our interview subject this month.

Bhutan’s citizens often claim their country is the original beyul — the hidden mountain sanctuary of Tibetan folklore. In a way, it has lived up to the fable, becoming a final safe harbor for Himalayan Buddhist culture.

— Ed.

Gleaning the barley field, Lungo

In the seventeenth century the villagers of Lungo rejected Zhabdrung, the founder of the Bhutanese state. All the families there died out, and the village was abandoned. Generations later, the Layap people began moving to abandoned Lungo farms.

Karma Yuden and baby Tenzie, Gasa Hot Springs

The Bhutanese make frequent pilgrimages to remote and often hidden hot springs throughout the country. Called tsha chu, they are places of healing, community, rest, and devotion. The water of each spring is different and is credited with having its own unique healing properties.

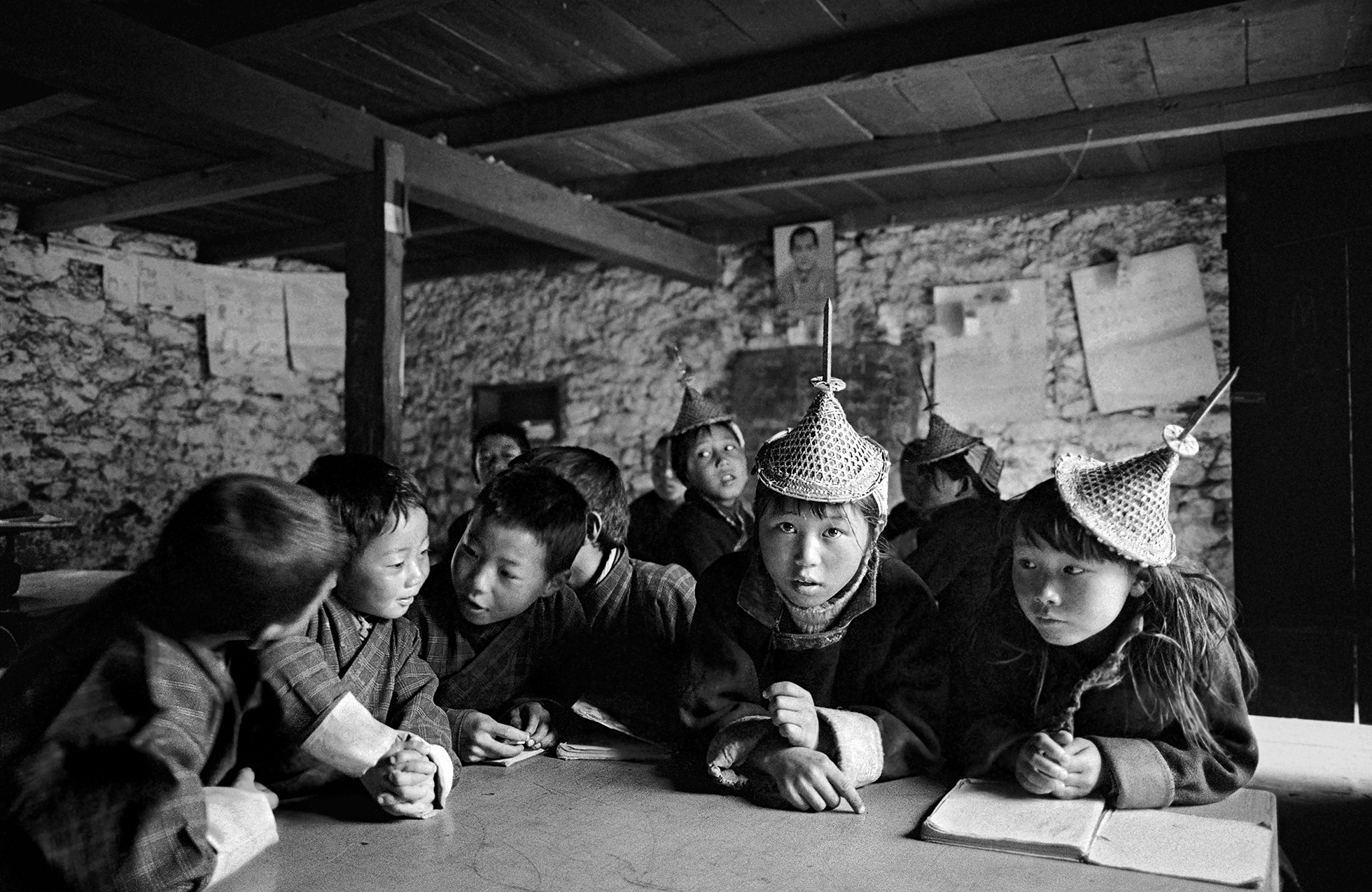

Laya School

After the end of theocracy and the establishment of monarchy in 1907, Bhutan began a gradual shift from monastic to secular education.

Thimphu commercial district

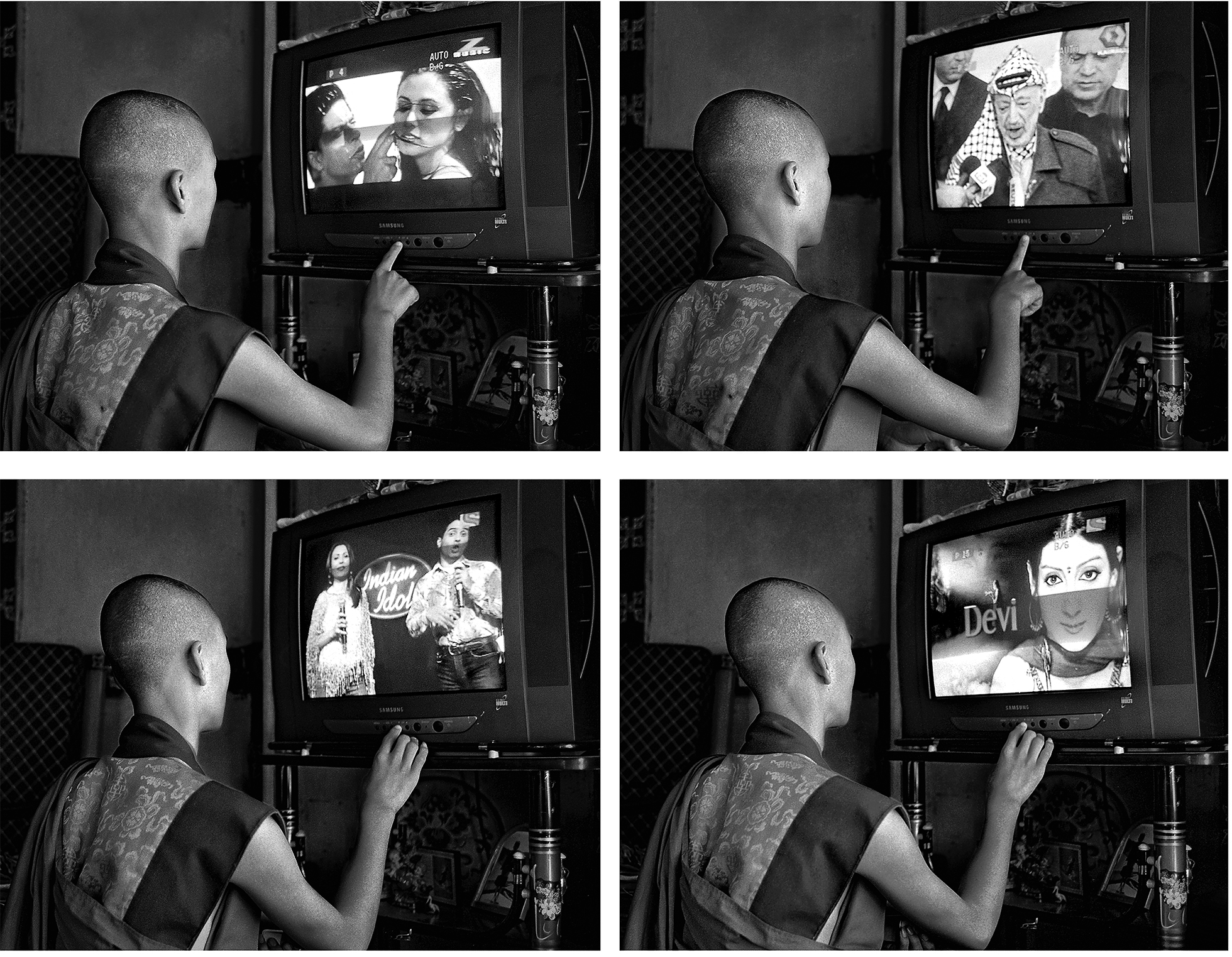

Pub Tshering, a monk, watching TV, Punakha

Television did not come to Bhutan until 1999. Before that the king would not allow it, fearing it would change the culture.

Dema (left) and Tshering, Gasa

For special ceremonies and formal occasions, Bhutanese women wear kiras: handmade, intricately patterned dresses of silk, wool, hemp, and cotton. To make one takes six months — if the woman has a good husband who helps with the cooking so his wife can spin and weave. “Some husbands are no good,” Dema said. “They won’t help. Their wives need nine months to weave a kira!”

The Crown Prince, now the Fifth King of Bhutan, talks to a little monk, Trongsa

In 2006 the Fourth King of Bhutan abdicated his throne, establishing his son (pictured, right) as king. The Fifth King ascended to the throne just as the country made the transition to democracy. The Fourth King now lives like a monk in a two-room log cabin in a forest just outside the capital. He is often spotted riding his bicycle or playing basketball in the public parks.