“Look, it’s just like the two of you — a set of twins,” our mother said brightly when she pulled into the driveway of the rambling two-story Victorian. Paul and I sat in the back seat, knees touching as we peered through the car windows, suspicious of the sagging porch, the peeling scrollwork, the crooked gutters brimming with the late-autumn detritus of colored leaves. Earlier we’d been told that the interior of the house was divided into two apartments joined only by a single umbilical staircase.

Across the street Lake Monona gleamed in the dusk light, its rocky lip just yards from our new front door. “Elizabeth, we should sleep on the second floor,” Paul, always the cautious one, whispered to me. “In case it floods.”

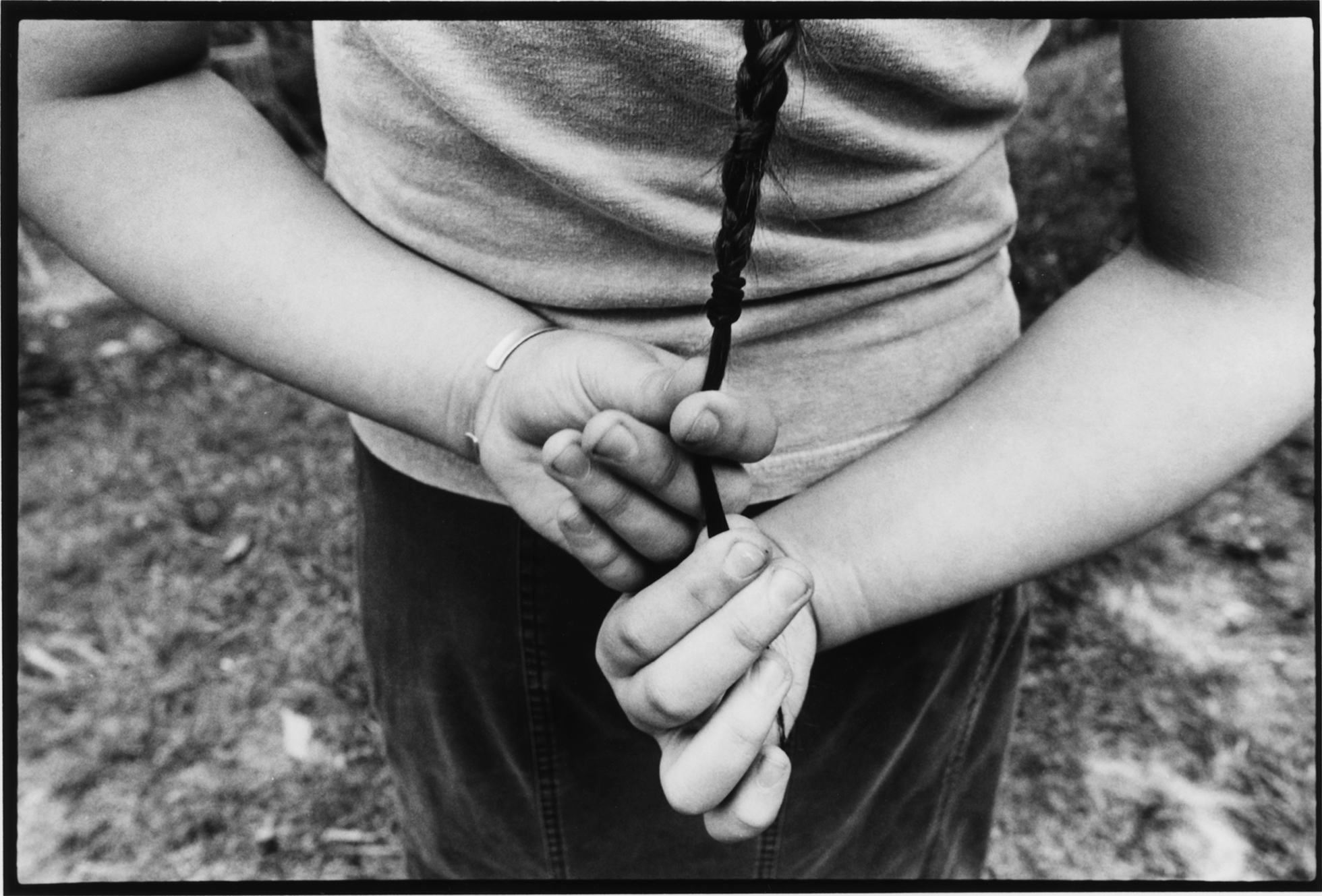

Our mother stepped out of the car, then helped Paul out by his elbow. Paul’s right hand had never fully formed, and on that day, as always, he wore a hooded sweat shirt with a front pocket so that his hand could nest there out of sight. An unborn rabbit of a hand is how I thought of it, a fist of pink flesh with fingers that could not open. Paul refused to let anyone touch it. Even me.

Our mother was a tall woman with a forceful gait, and she hurried us up the steps and waggled the key in the rusty lock. When the key broke off, she stood for a moment biting her lip, eyes scrunched, then promptly went around back to climb in through a window. She hoisted herself inside, then pulled us up by our arms, practiced at easing bodies through small openings. For as long as we could remember, she had been studying to become an obstetrician.

Once inside, our mother appeared diminished by the high ceilings. She walked slowly through the first-floor dining room, past the bare walls and tall, shadeless windows. The floorboards creaked underfoot, and she started once, looking back at us, then laughed as she flipped on a light. Paul and I hovered in the kitchen doorway, hands clasped, watching her move about in her white clogs and lab coat.

“Well, come on. What do you say we check out your rooms upstairs?” she called from the foyer. I felt Paul shiver as we followed her up the staircase.

“They’re splitting up,” I announced quietly to Paul as we reached the top step, our parents’ separation suddenly apparent to me. His body stiffened. He withdrew his good hand from mine and stuffed it into his front pocket, where I could see him begin to caress his fist. Our mother turned to face us in the hall, an ashen pallor in her cheeks. “No, silly,” she said, forcing a grin. “Your father and I are just trying something different.” She pulled a tube of lipstick from her lab-coat pocket and swished it across her lips. Then she kissed us both, leaving pink circles all over our faces, calling, “Swiss cheese, Swiss cheese.”

We moved in a week later. Our mother took the upstairs apartment. Paul and I took the two upstairs rooms in the front, where we had views of the lake and could watch from our beds as fishing boats set out for deeper waters. At night the traffic on the highway that led to downtown Madison, Wisconsin, stretched across the darkness like a string of Christmas lights.

Our father lived mostly in one bedroom on the first floor, and it sat squarely beneath ours; he called it his “study.” Into it he moved a sofa bed and a badly nicked Queen Anne dresser he’d cribbed from the curb. On the walls he hung photographs we had never seen before, many of them old black-and-white portraits of him before we were born. One picture showed him bare chested with long, wavy hair, dangling by one arm from a fire escape. His free hand was tucked into the waist of wide-legged corduroys that fanned out above his hairy toes. His grin was topped by a thick mustache. This he hung across from the sofa bed where he slept. Sometimes in the afternoons we stood gaping at our father in that picture, feeling its strange charge. The man in the photo looked nothing like the father we knew, who was hairless now except for a salt-and-pepper goatee and heavy eyebrows. “We didn’t exist then,” Paul said, running his finger down the picture frame’s glass.

“Don’t smudge,” I whispered.

“I’m only touching our reflection.” Paul traced our heads but yanked his hand back when he got to the top of our father’s pants. “Who do you think took the picture?” he asked.

I tiptoed to the doorway to make sure our father was still in the kitchen. “Not Mommy,” I whispered.

Paul turned to me and blinked his heavy-lidded eyes. I crossed the room and took his good hand, and together we went outside to chuck rocks into the water.

Just after winter’s first snowfall I heard an unfamiliar voice in the study. It was a sparkling night, the lake transformed by snow into a plate of white sugar, reminding me of the cookies we used to make with our father after school. Through the vents I heard muffled laughter and two low voices. I recognized my father’s by his inflection; his voice rose and fell, distinctly songlike. The other voice was huskier, more monotone.

“Who’s down there?” asked Paul when I stole into his room. “Could it be . . . ?”

I looked hard at Paul, rolled up like a sausage in his Superman blanket. “Don’t say it,” I said. “There’s no such thing as Santa Claus.”

“I know that,” Paul huffed. He turned onto his side to make room for me to sit on his bed. A second later he asked, “Who else do you think it could be?”

I gazed at the stars through the window, feeling my eyes moisten from the draft. The voices trickled below us like water under ice. Eventually jazz music wafted up from the study, and we fell asleep. In the morning, when Paul and I went downstairs, there was no sign of the visitor, except for a pair of wineglasses on the counter by the sink.

Our mother always brought us to school, dropping us off on her way to the hospital. In the back seat Paul and I listened to each other’s heartbeats through her stethoscope. Our mother was quiet on those mornings, averse to playing the tape deck, even to listen to Bob Dylan, her steady favorite. Once, I touched the corner of her eye to see if she was crying, and she swatted my hand, hard. It was the only time she ever hit me, and it stung. Paul gave me his glove, but he wouldn’t let me share the pocket of his hoodie where his right hand was.

Minutes later, though, Paul took his right hand out of his pocket and examined it quietly in his lap, as if he were giving it a drink of air. My brother once told me that, at night, sometimes he could feel his fingers almost open as he drifted off to sleep. But in the cold morning light his hand had a raw, clenched look. The skin was shiny, pinker than the skin anywhere else on his body, with fingers curled tightly into a knot like the bud of a mum, self-contained and set to spring.

As part of the new arrangement Paul and I spent half our evenings upstairs and half downstairs. Our father had been, among other things, a sous-chef, and he fixed us elaborate meals: bowls of alphabet soup with pesto rémoulade, pan-seared sea scallops with vanilla dipping sauce, macaroni and cheese with tea-smoked tomatoes. He praised us for our appetites and stroked our hair as if we were a pair of cats while he stood over us and smoked a clove cigarette. Usually he did not eat; most nights he thumbed through magazines about camera equipment or motorcycles and jumped from the table to the fridge, refilling our glasses with milk. He often took calls in his study, where he closed the door. Whenever he emerged, he said, “Sorry, kids. How is everything? Can I get you anything else?” He’d stand pertly before us like a waiter, his eyes gleaming. Sometimes he’d swoop down upon the table with a bowl of radishes and carve them into roses. Or he would say, “When I was a chef . . .” and then melt some chocolate with Karo syrup and demonstrate how to mold fondant. He taught us a different trick every week; he said we needed a creative outlet.

“Carve me something,” he once said, passing us a bag of carrots and a set of blunt cheese knives. “Whatever’s on your mind.”

“When were you a chef?” my brother asked.

“Years ago,” he said as he waved a peeler.

“Before we were born?”

Our father nodded his bald dome, his eyes set on a carrot. He rarely spoke of the days before our birth, although he was surrounded by pictures of himself living in that world. We knew from our mother that our parents had met at an outdoor concert and that in the days before we were born they lived in a housing cooperative on the other side of the lake, where they had a garden with raspberry bushes and a wood-fired sauna that they relaxed in when it snowed. When they got really hot, they would roll around naked in the snow.

The meals our mother prepared were much simpler. Bleary-eyed from school, she heated up Hungry-Man dinners for us in her oven. The box covers always made these meals look delicious, but the meat tasted spongy, and the vegetables were grayer than in the photographs.

Our mother often flipped through her textbooks at the table. Her nails, chewed to the quick, flashed over colorful illustrations of uteruses and milky photographs of fetuses tethered to the womb. Seated on either side of her, we craned our necks over our foil trays to see the pictures, fascinated by the idea that we had once been inside her, entombed in red tissue.

“How did we breathe?” I always asked.

“Did you know it was us?” my brother wanted to know.

Of course we knew the answers, but every now and then these questions elicited new, more-elaborate replies, especially when our mother was tired. Once, she revealed that she had planned to give birth to us at home, but we had come early. She hadn’t liked hospitals then and had never had an ultrasound — which, she explained, allowed the doctors to know the number of babies inside. “It was quite a surprise,” she said, yawning over her supper.

We blinked at her. “You thought there was just one of us?” I asked.

“Yes,” she nodded, folding her arms on the table. “Actually I was pretty sure I was having a girl.”

“And Dad didn’t know?” Paul asked.

“Let’s just say we were surprised by lots of things back then, and we didn’t plan very carefully.” When she looked over at us, she must have seen the worry in our eyes. “Lighten up, everybody,” she chirped. “Look how everything has worked out.”

It had never occurred to Paul or me that one of us had been unexpected. “You came first,” he announced the next day in the yard. “Then I came. If I hadn’t been born, you’d be standing here alone.” He scooped up a handful of snow and held it aloft in his mitten, as if he wasn’t sure whether to throw it or let it fall from his hand.

“Where would you be?” I asked, kicking at some ice that had crusted over the curb.

He shrugged and looked out across the lake. It was morning, the sun gleaming on the ice. The fishing shanties looked like bonnets arranged haphazardly on the surface of the lake.

“I’d be in the sky still,” he said quietly.

“Or maybe part of another family,” I told him. “That could be your dad.” I pointed my mitten toward a man carrying a cooler, striding across the ice. When he got near the center, he set his cooler down and straightened his hat. He looked back at the shore and waved before pulling down his face mask.

“Yes,” Paul said softly. “Or I might live in China.”

“Or Russia,” I said.

“Or Barbados,” he said, which was a country listed in one of his pirate books.

“You might have a perfect hand,” I offered without thinking.

Paul glared at me, then took the snow he’d collected and pitched it right in my face. It struck the bridge of my nose and sent a sharp pain bouncing through the back of my skull.

“I was kidding,” I called after Paul as he ran home. I held my mittens over my nose and stood for a long time, fighting back tears as I looked at the house, watching for some sign in one of the top windows.

Later that day Paul asked our father if he could move his bedroom downstairs. “No,” I heard our father say, “I listen to music at night, and it would keep you awake.”

Christmas passed quietly. Paul and I asked for walkie-talkies, but instead we received socks and books and watercolors. In the days after Christmas our father began wearing a brand-new pair of leather pants, and he spent more time in his study, which visibly frustrated our mother. It seemed as if they were talking to each other less every day.

In a way, seeing my parents separate prepared me for the distance that came between Paul and me. In January he began shutting his bedroom door at night, and when he was awake, he often went outside to play alone. I’d see him through the window in his navy snowsuit, standing at the edge of the lake — we were not allowed on the ice — and the sight of him alone out there, his pointy hood framed against the gray sky, reinforced my own independence, so that I began to convince myself that I, too, preferred to play alone. I could talk myself into believing that he was just a neighbor boy playing in the snow or a character on television whom I watched from a distant couch. Sometimes I led pretend tours of the house. Standing before Paul’s bedroom door, I’d announce to an imaginary audience, “And this is just where we store extra bedding and bath salts.”

While Paul played outside, I moved through the rooms, exploring the house on my own. The floor plans of our parents’ apartments were similar, and yet their rooms could not have looked more different. Our mother’s kitchen cupboards were empty, and her houseplants were withered, the tips of their leaves browning. Her bedroom, full of perfumes and candles, was the only place I liked. I loved to curl up in her bed, pull the covers over my head, and inhale the floral smell of her pillow.

Downstairs our father treated his mostly empty space like a gallery. The freshly painted walls gave off a surgical sheen, and there weren’t any plants or throw rugs, just large coffee-table books in carefully arranged towers with wineglasses occasionally perched on them, sometimes half full of sour-smelling wine. And, unlike my mother’s living room — which contained the overstuffed furniture from our last house, including a rose sectional — my father had a few cane chairs clustered around a standing ashtray. There was a feeling of bleak transition in my father’s rooms, and yet his well-stocked kitchen, full of dried fruit in Mason jars and premium teas in silver canisters, gave me the feeling of being in a health-food store or a museum where someone cared deeply for little dried-up things.

One afternoon my father found me sitting on his sofa bed, looking out the window at my brother by the lake.

“What is he doing out there by himself?” my father asked, pouring whiskey from a flask on the dresser.

“He’s playing,” I said.

“Playing what?” My father moved to the window, ran a hand over his head, and let it rest on the back of his neck.

“Only Child,” I told him.

My father stood at the window for a long time, sipping his whiskey.

Later that evening our father and mother spent a long time talking in the upstairs bathroom. When they came out, my father left the house and my mother preheated the oven for dinner. That night, on our pillows, there were walkie-talkies.

The walkie-talkies brought Paul and me together again yet allowed us to roam separate floors, comparing notes. “Mom finally bought peanut butter,” I’d walkie to Paul, who would be scouring Dad’s cupboards below.

“Dad has jelly, over ’n’ out,” Paul would radio back.

That January Paul and I slept in our respective beds and listened to the lake ice crack and talked to each other through static. “Did you hear that?”

“Yes.”

“That was an icicle falling from the roof.”

Sometimes our parents commandeered our radio communications, sending Paul or me to the other floor to rework the meal schedule or to inquire about how much gas was in the car they still shared.

“Dad says it’s on empty,” I’d radio to Paul.

“Shit,” Paul’s voice would crackle. There’d be a pause, then his voice again: “He’s home most of the day, and he can’t put gas in the goddamn car. Why is that? Mom wants an answer.”

“Tell Mom that Dad sends two eye rolls,” I’d walkie to Paul.

“Mom says to report back upstairs. Do you read me?”

I’d run the faucet and hold the walkie-talkie over the sink, a trick that Dad had showed me. “Sorry, Paul, you’re breaking up,” I’d bellow. That always made Dad smile.

Late one night we heard a motorcycle pull up to our house and watched from our windows as one of the two leather-clad figures dismounted. From under the egglike helmet our father’s baldness emerged. He stood in the street talking to the driver of the motorcycle, throwing his head back periodically to laugh. After a few minutes he crossed the snow toward the house, and we watched from our separate bedrooms as the motorcyclist started for the highway, destined to become one of the taillights that winked at us across the dark lake.

“Do you think we should tell Mom?” Paul radioed.

“I think she knows, Paul,” I radioed back. “That’s why we moved here.”

Paul was silent.

A few moments later Paul appeared in my doorway with his sleeping bag. “Elizabeth,” he said, approaching my bed, “do you think they wish we’d never been born?”

I rolled over to make room for Paul. He slid in next to me, his pajamas snapping with static. “I wish they’d tell us,” I said.

It seemed possible to me then that our parents might begin to disappear in the night, returning only to feed and water us as though we were a pair of hamsters. A friend at school whose parents had divorced had moved in with her grandmother and saw her mother only on holidays. Another friend once described how her father packed a suitcase for a business trip to Canada and never returned, never even called. Parents seemed temporary, like household appliances.

“Paul,” I whispered, “we have only each other.” But he was already asleep, his body coiled in a ball. I curled around him but slept sporadically, waking off and on to the sound of snow sliding off the roof in sheets.

Our father worked part time as a janitor at a chemistry lab, but really he was a photographer. Every day he took a picture of something that he considered “essential.” We’d descend the stairs with our school bags and see him in his flannel pajamas at the front door, surveying the horizon through the lens of his camera. He told us the photos were for a gallery show. Mostly our father took pictures of the lake, but sometimes he took pictures of Paul and me making snow angels or playing dress-up or eating breakfast at his table.

“How come you never take pictures of Jean?” Paul asked one morning when our father came inside with his camera, stomping snow off his boots. Jean was our mother’s name — it was the first time Paul had called her something other than “Mom.” Our father didn’t answer. He went to the fridge and poured himself a glass of orange juice.

“Isn’t she essential?” Paul asked politely, nibbling at his toast. Our father turned around and set his eyes squarely on Paul, then on me.

“Jean does not care to participate,” he said. “She and I, as you have noticed, are rather on the outs.”

“Do you still love her?” I asked, encouraged by Paul’s boldness.

Our father took a deep breath and squinted at the ceiling as if he could almost make out our mother on the upper floor. “No, not in the same way,” he said finally.

Paul and I exchanged glances. When our father left the room, I said to Paul, “We can’t ever break up.”

He stared at me. “No,” he said. “We came here together.”

Our father returned wearing his leather pants and a sweater, humming under his breath. He lit a cigarette off the gas stove and briskly refilled our juice glasses. “You’re more like the mother now,” Paul observed.

Our father tilted his head back and laughed, two tusks of smoke billowing from his nose. “Now that’s a good one,” he said, giving Paul’s shoulder a shake. “I’ll have to tell Dom.”

Silence fell over the kitchen. “Who?” I asked, as our father carried our plates to the sink.

“No one,” he called over his shoulder. “Now finish your breakfasts.”

Courtesy of the Salt Institue, Portland, ME

It was after Valentine’s Day when Paul confronted our father about his lover. We’d heard his motorcycle, seen his footprints in the snow, smelled his cologne in the entryway — a thick, mossy scent that Paul claimed smelled like bear. On that day we were released from school a few hours early in advance of a blizzard, only to find the door to the house locked. A friend’s parent had dropped us off, assured by our mother over the phone that our father was home. We knocked on the door for several minutes, staring at a pair of unfamiliar boots on the stoop while snow blew across our faces.

Finally our father appeared at the door in his robe, checking his watch. “What are you doing here?”

“School was canceled,” I shouted.

From the front door we could see into the kitchen, where a bouquet of roses rested on the counter, still wrapped in clear plastic. An orange parka — not our father’s — was draped across the back of a chair. Then his bedroom door clicked shut.

“What the hell took you so long?” Paul blurted out, pushing past him.

“Watch your mouth, mister.” Our father caught Paul’s arm.

“You’re gay,” Paul growled, jerking away. He tore up the stairs two at a time.

Our father stepped back. He appeared small standing in the foyer, his feet jammed into pointy Chinese slippers, his face ashen.

“Elizabeth,” he pleaded. I was still on the porch, not sure whether to enter the house or run back into the cold. My father reached out to me, and I turned, swinging my metal lunchbox and grazing his knuckles by accident. The fact that I had hit him scared me more than the idea of going back into the snow, and I fled down the front steps and toward the lake, venturing over the lip we had been forbidden to cross. I ran as fast as I could, skidding and sliding, exhilarated by the inherent danger of being alone on the ice.

“If you go out on the ice,” our parents had warned, “you could fall in, and we’d lose you forever.”

There was no sign that my father had come running after me. I felt strangely brazen, and for a long moment I just stood there, relishing the cold, blowing on my bare hands since I had forgotten to wear my mittens that day. The lake was empty except for the fishing shacks. In the shadow of their snow-covered rooftops, I realized that I was hidden from view. Out here, I thought, one really could disappear.

I pushed at the door of a shanty and found myself inside a small, cavelike room with a cot along one side and a sheet of plywood covering the hole in the ice. There was a braided carpet and a lawn chair with a red cooler next to it. A small propane heater by the door still emanated heat — someone had recently left — and on the cot there was a stack of blankets and a paper bag from Mister Donut. There was even a window and a small table, along with coat hooks and a rack of fishing rods. It was perfect, like a winter playhouse.

I closed the door behind me. Outside the wind sang against the metal siding, but inside it was still. Then I heard a pinched voice calling my name. I moved toward the window, where I could just barely make out my father in a brown parka, standing on the porch with another man, who was wearing the orange parka we’d seen earlier, looking up and down the sidewalk. The wind had already blown away my tracks.

I sat down on the cot and flipped on the heater. I watched through the window as my father and the man in the orange parka circled the house, then took off toward the playground. When they disappeared from view, I hung my coat on a hook, kicked my boots off, and pulled the blankets over me, nestling into the scent of mothballs and fish bait. I reached for the paper bag, where I found two pink-frosted doughnuts. A six-pack of ginger ale was in the cooler, and I helped myself to a can.

After a while the shadows lengthened. The room grew dark except for the heater’s blue flame. I nibbled the first doughnut to a crumbly ring, then worked at the second with my fingernails, chipping off pink shards of frosting. The temperature began to drop, the cold overpowering the small heater, and I pulled the covers up around my ears. It was then that I felt my first twinge of fear: What if I froze to death out here? What if I fell through the ice on my way home?

It was dark across the road; not even Paul’s bedroom light was on. Maybe no one cared, I thought. I drew the blankets over my head and rested my chin on the sill, thinking back to our old house on Orchard Street, remembering the flowers I’d helped my mother plant along the porch and the tire swing our father rigged up for Paul and me.

Then I saw them coming across the ice, three bundled figures, each swinging a flashlight: my father in his brown parka; my mother in her green one; and Paul in his navy snowsuit, waving a blinking emergency flashlight. They were going from shack to shack, knocking on all the doors.

“Elizabeth!” I heard my father shout.

“Lizzie!” came my brother’s plaintive cry.

I sank down on the cot. “In here,” I called.

Soon there were muffled footsteps outside the door. “It’s open,” I said.

My father pushed the door back. Flashlight beams swept across the walls, settling on the cot. I turned away from the bright lights and drew my knees to my chest.

“Have you been out here the whole time?” asked my father.

“Oh my God!” my mother wailed as she lunged across the plywood board. “Is that the hole?” she asked, turning back to my father. “She could have fallen in!”

“It’s not that big,” my father assured her. He squatted and lifted the board. A black hole glistened there, rimmed with silver — the size of a paint can. My brother’s flashlight pulsed across its dark mouth.

“Turn that off,” my father called over his shoulder. He let the plank fall back into place, and the room went dark.

“Oh, my baby,” my mother whispered, kissing my forehead. “Are you OK?”

“That was a terrible joke to play,” my father said, his voice suddenly gruff. He sat down next to me and began rummaging for my coat and boots.

“Paul, turn on the light,” my father called.

There was a shuffling sound by the door, but no light.

“Paul,” my father said again. “Come on, let’s pack up and get out of here.”

Again, nothing. From across the dark room I could hear my brother breathing. He was stationed against the door, refusing to move.

“Listen,” my father said, his voice cracking. I nestled into my mother’s lap, my feet against my father’s thighs. I could make out my father removing his glove to rub his face, and I felt my mother slump back against the wall of the shack. “Listen,” my father began again, but it led to nothing. My mother reached over to him, and he took her hand. I stepped into my snow boots and stood up, feeling the plywood board give just a little under my weight.

“Gordy,” my mother said to my father. “Gordy, it’s going to be OK.” Our father took her in his arms and cradled her.

Paul walked over to the cot. For several long minutes we peered through the dark. Then our mother beat a mitten against our father’s chest, and our father said, “I know, I know.” Paul shifted toward me and pulled my bare hand into his pocket — his right pocket. The light was dim, the air cold, the wind outside the walls shrill, but Paul’s pocket was warm. His gnarled fist was smooth and round and sturdy, like a stone.

We left the ice shanty in disarray — blankets rumpled, doughnuts half eaten, the paper bag balled up at the foot of the cot. The fisherman, when he returned, probably thought some young couple had found their way there and made a night’s nest. He would never guess a family of four had crammed inside, fogged the window with their breath, and had a brief respite from their differences.

After that evening our father introduced us to his friend Dom, a red-bearded chemist who taught us how to melt small glass tubes over Bunsen burners. Now and again our mother joined us for dinner, the five of us crowded around the table, the three adults drinking wine in the firelight while Paul and I constructed fragile, miniature glass animals and trees that remained lined up along the kitchen windowsills for years to come.